Download a PDF of this Backgrounder.

Steven A. Camarota is the director of research and Karen Zeigler is a demographer at the Center.

A prior analysis by the Center for Immigration Studies of Census Bureau data showed that the age at which immigrants are arriving in America had increased dramatically since 2000. Newly released data for 2019 shows that immigrants (legal and illegal combined) are still coming to America at much older ages than was the case a decade or two ago. However, the trend has stabilized and, in fact, new immigrants in 2019 were slightly younger than newcomers in 2017 and 2018.

The fact that new immigrants are arriving at older ages than in 2000 or 2010 has implications for the often-made argument that immigration makes the country significantly younger. The findings also have implications for public coffers because prior research indicates that younger immigrants tend to have a more positive lifetime fiscal impact than older immigrants. We also find that the nation's overall immigrant population (new arrivals and established immigrants) is aging rapidly.

Among the findings:

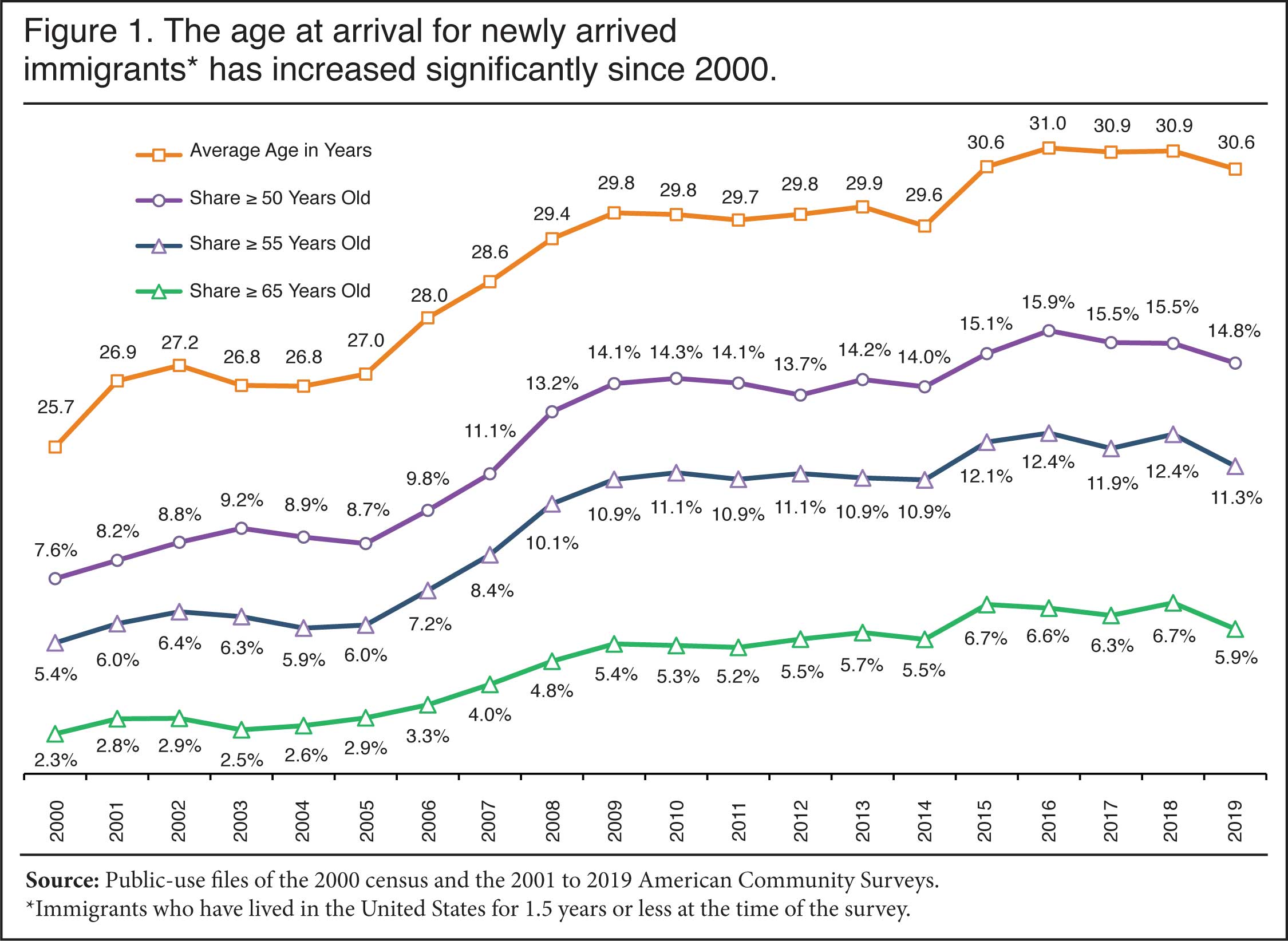

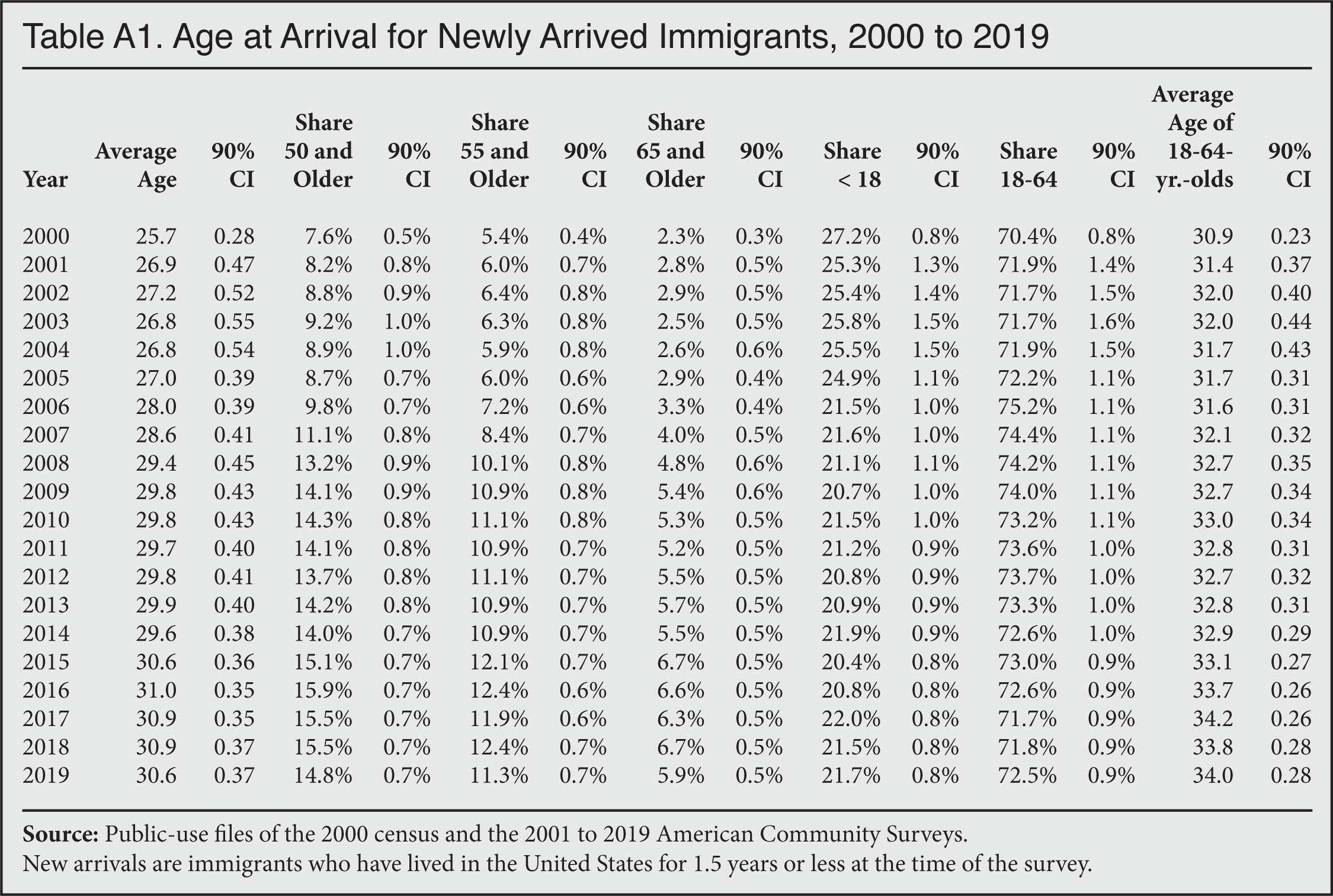

- The average age of newly arrived legal and illegal immigrants was 31 years in 2019, compared to 26 years in 2000. The newly arrived are defined as those who have lived in the country for 1.5 years or less at the time of the survey.

- Older age groups have seen the largest increases. The share of newly arrived immigrants who are 50 and older in 2019 was nearly double what it was in 2000 — 15 percent vs. 8 percent.

- The share of newcomers 55 and older in 2019 was 11 percent, double the 5 percent in 2000. The share 65 and older was 6 percent in 2019, compared to just 2 percent in 2000.

- While the average age and share of new arrivals in the older age groups remain higher in 2019 than in 2000 or even 2010, they are slightly lower than they were in 2017 and 2018, indicating that the age at which immigrants come to America is no longer increasing.

- On an annual basis, 224,000 immigrants 50 and older settle in the country, including 172,000 55 and older, and 89,000 who are 65 and older.

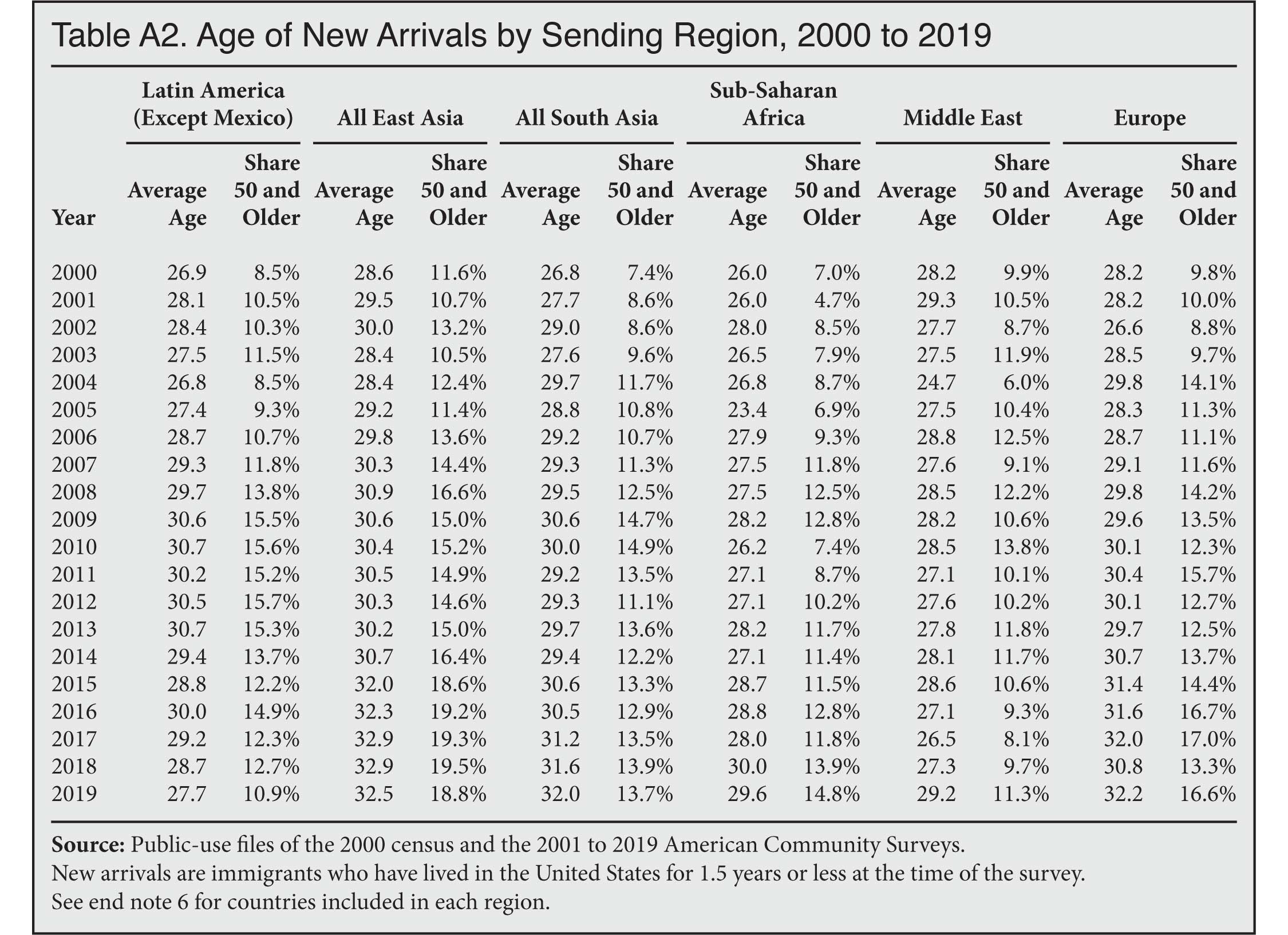

- The rise in the age at arrival for immigrants is a broad phenomenon affecting immigrants from most, though not all, of the primary sending regions and top sending countries.

- Several factors likely explain the rising age of new arrivals, including significant population aging in all of the top immigrant-sending regions of the world, an increase in the number of green cards going to the parents of U.S. citizens, and a decline in new illegal immigration relative to earlier years.

Aging of the overall immigrant population:

- The average age of all immigrants — newcomers and established immigrants — increased from 39 years to 46 years between 2000 and 2019. This is more than twice as fast as the average age increase for the nation's overall population.

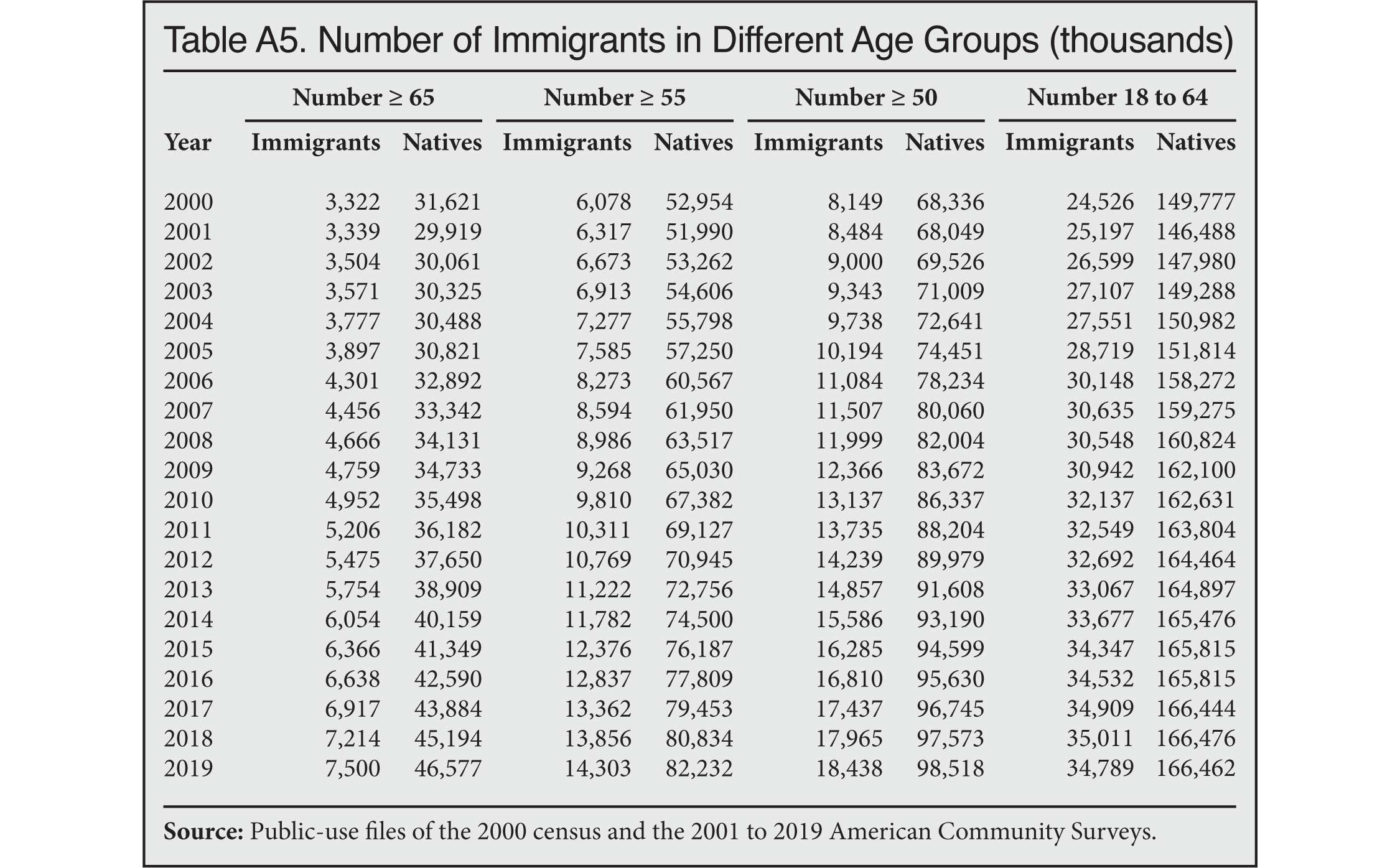

- The number and share of all immigrants 65 and older has exploded; more than doubling from 3.3 million in 2000 to 7.5 million in 2019.

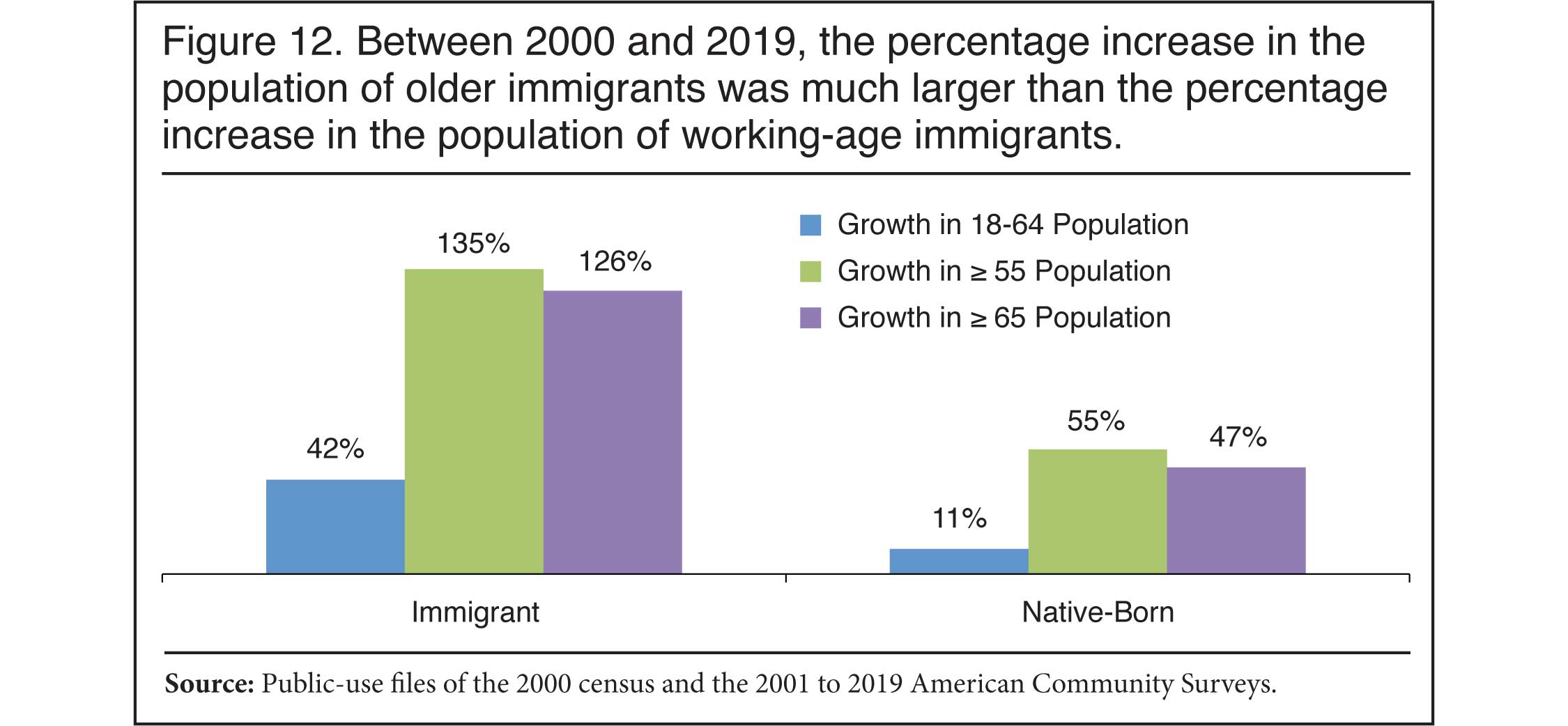

- The number of immigrants 65 and older grew by 126 percent between 2000 and 2019, dramatically faster than the 42 percent increase in the number of working-age immigrants 18 to 64.

- The increase in the age of new arrivals contributed to the rapid aging in the overall immigrant population, though the primary reason is simply the natural aging of immigrants already in the country. Moreover, by definition, all births in the United States to immigrants add to the native-born population, not the immigrant population. This causes the immigrant population to grow old quickly.

Introduction

Traditionally, one of the benefits of immigration is that new arrivals generally come at young ages, helping to offset population aging in advanced industrial democracies like the United States, which have high life expectancies and low fertility. The question of the degree to which immigration slows population aging in receiving countries has been well studied by demographers for some time, and the research shows that immigration to low-fertility countries like the United States can add a larger number of people to the population, but has only a modest impact on slowing population aging.1 This analysis finds that even this modest impact is likely becoming smaller as the age of new immigrants is now higher than it was two decades ago.

To measure the age of new arrivals, we use the public-use files of the American Community Survey (ACS) collected by the Census Bureau, which asks all respondents the year they came to the United States to live. New arrivals are defined as those who came to the United States in the calendar year prior to the year of the survey or in the year of the survey. Since the ACS represents the population on July 1 of each year, new immigrants are those who have lived in the country for no more than 1.5 years. Alternative definitions of new arrivals also show significant population aging. We use the terms "new immigrants", "newly arrived immigrants", "new arrivals", and "newcomers" synonymously in this report to describe immigrants who came to the United States in the 1.5 years prior to the survey. The ACS includes both legal and illegal immigrants, typically referred to as "foreign-born" by the Census Bureau. These are all individuals who were not U.S. citizens at birth.2

Our analysis shows that there has been a marked increase in the age at which immigrants arrive in the United States, though in the last two years that increase has abated. Newcomers in 2019 were slightly younger than in 2017 and 2018, though they remain older than they were in 2000 or 2010. We also find that the overall immigrant population, not just new arrivals, is aging rapidly.

Age at Arrival

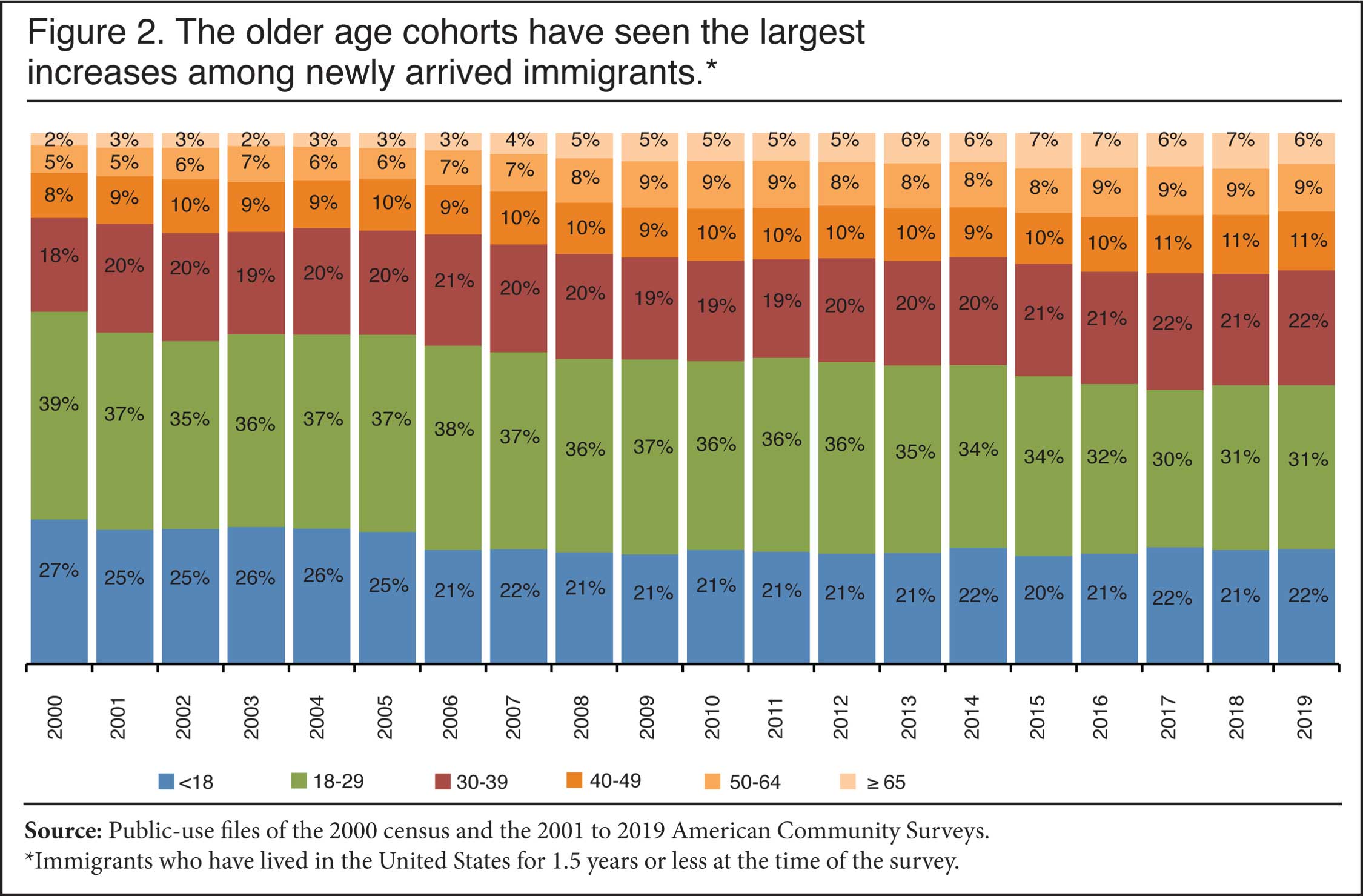

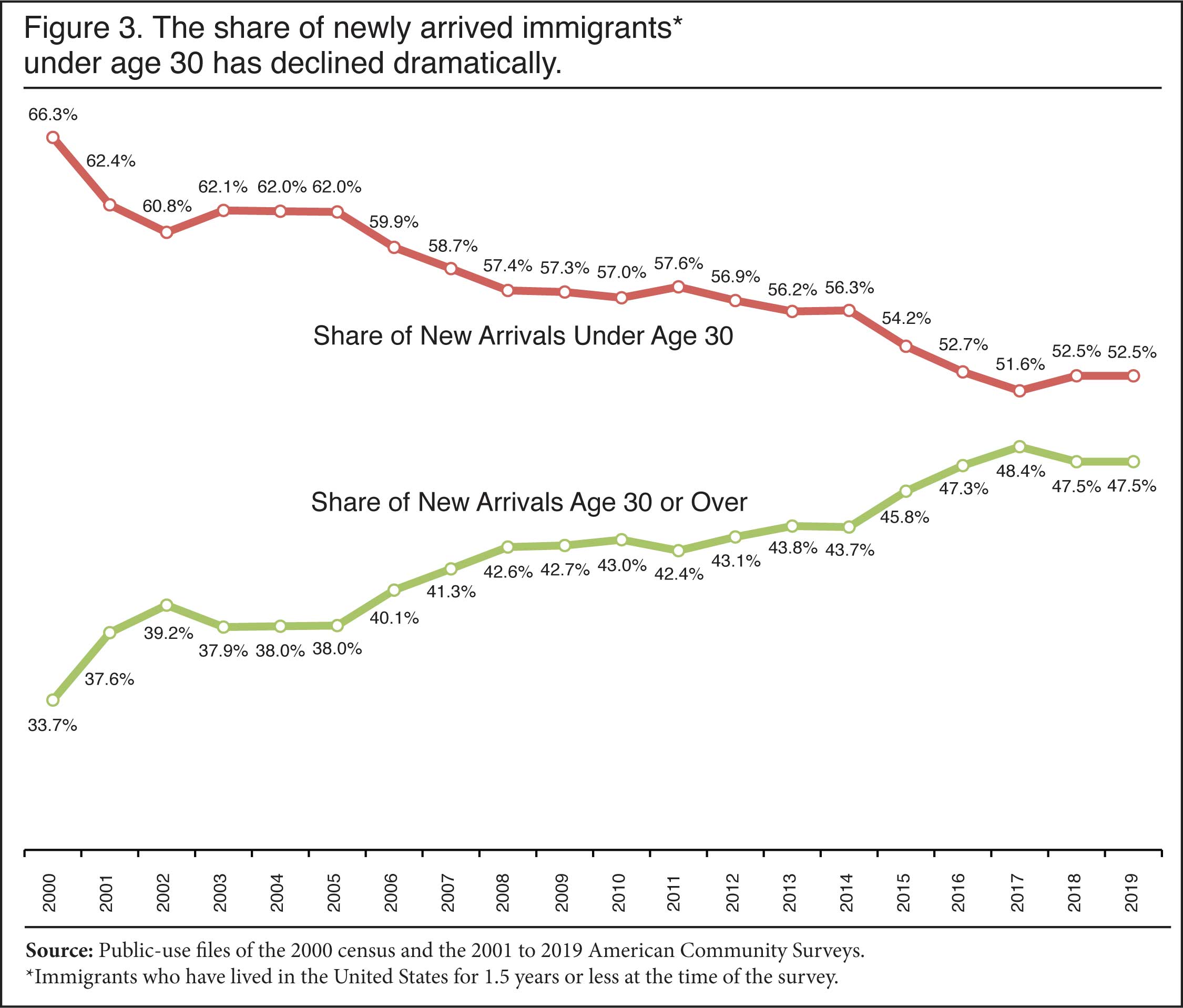

Arriving Immigrants Are Much Older. Figure 1 shows the dramatic increase in the age of newly arrived immigrants. The average age at arrival was nearly five years older in 2019 than it was in 2000 — 25.7 years vs. 30.6 years. The figure shows that older age groups have seen the largest increases. The share of newly arrived immigrants who are over the age of 50 roughly doubled, from 8 percent to 15 percent between 2000 and 2019; and the share 65 and older nearly tripled, from 2 percent to 6 percent. While we focus on those immigrants who have lived in the country for 1.5 years or less at the time of the survey, other definitions of "new arrivals" show the same increase in age.3 Figure 2 shows that the share of new immigrants arriving in the older age cohorts has increased the most since 2000. As older age groups make up a larger share of new arrivals, the shares in the younger age groups have declined significantly. Figure 3 shows the very large decline in the share of new immigrants who are coming to the United States under the age of 30. The share under age 30 has fallen from roughly two-thirds to about half.

|

|

|

Figures 1 through 3 show that newly arrived immigrants in 2019 were a good deal older than in 2000, but since 2017 new immigrants have become somewhat younger. So the age at arrival of immigrants is no longer increasing. It is unknown if this trend will continue.

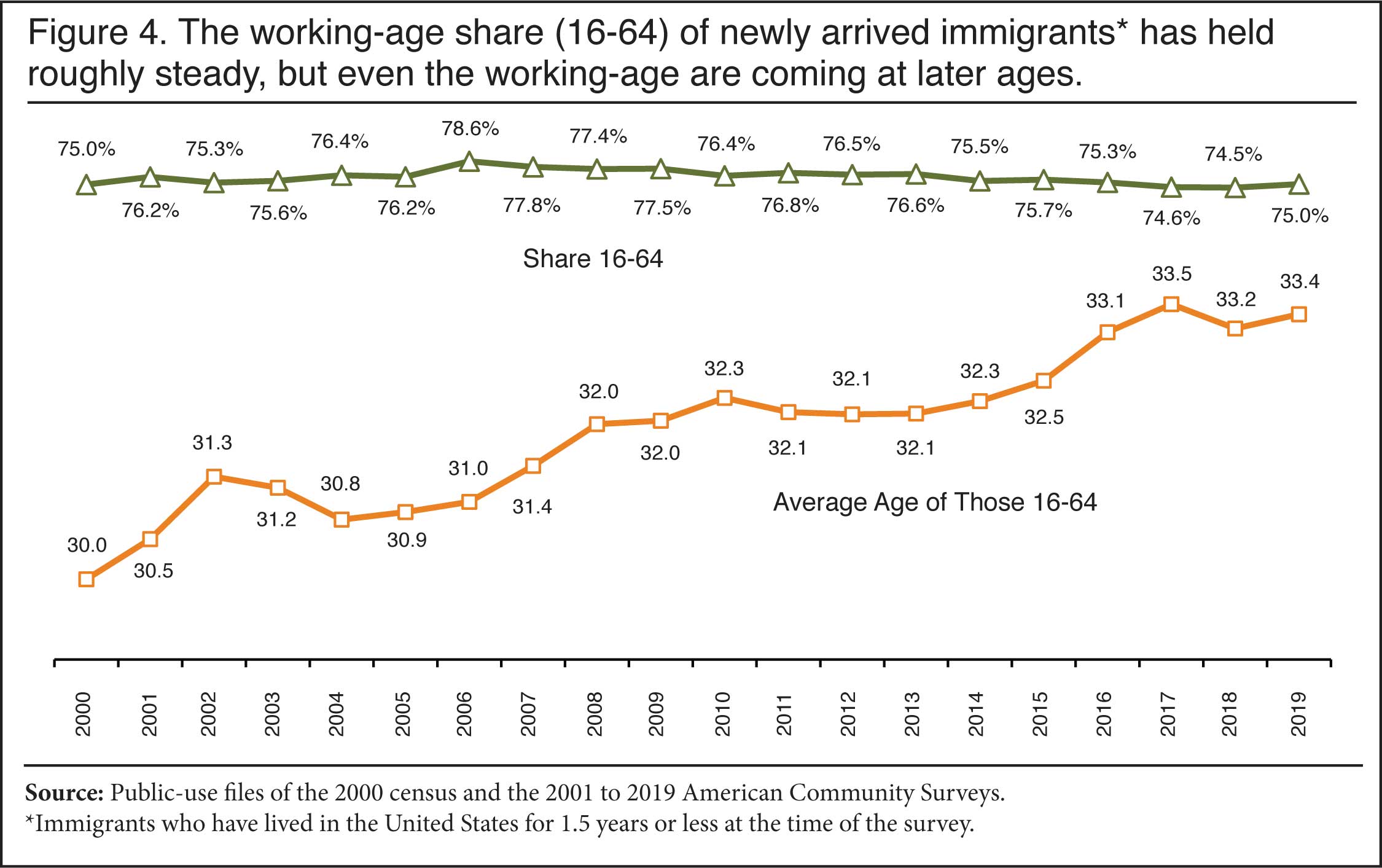

The Working-Age Share. Figure 4 examines the share of new immigrants who are of working-age (defined as 16 to 64). The share has held roughly steady, with some decline in the most recent years. However, even among the working-age, there has been a 3.3-year increase in the average age. This is a larger decline than it may seem because the average age only reflects the age distribution of those ages 16 to 64. Averages are often heavily impacted by values on the tails of the distribution — the young and old. In Figure 4, new arrivals under age 16 and over 64 are excluded, yet there is still a significant increase in the average age. As we have seen, more working-age immigrants are coming in their 30s, 40s, 50s, and 60s, rather than teens and 20s as was the case in the past. This explains the results in Figure 4.

|

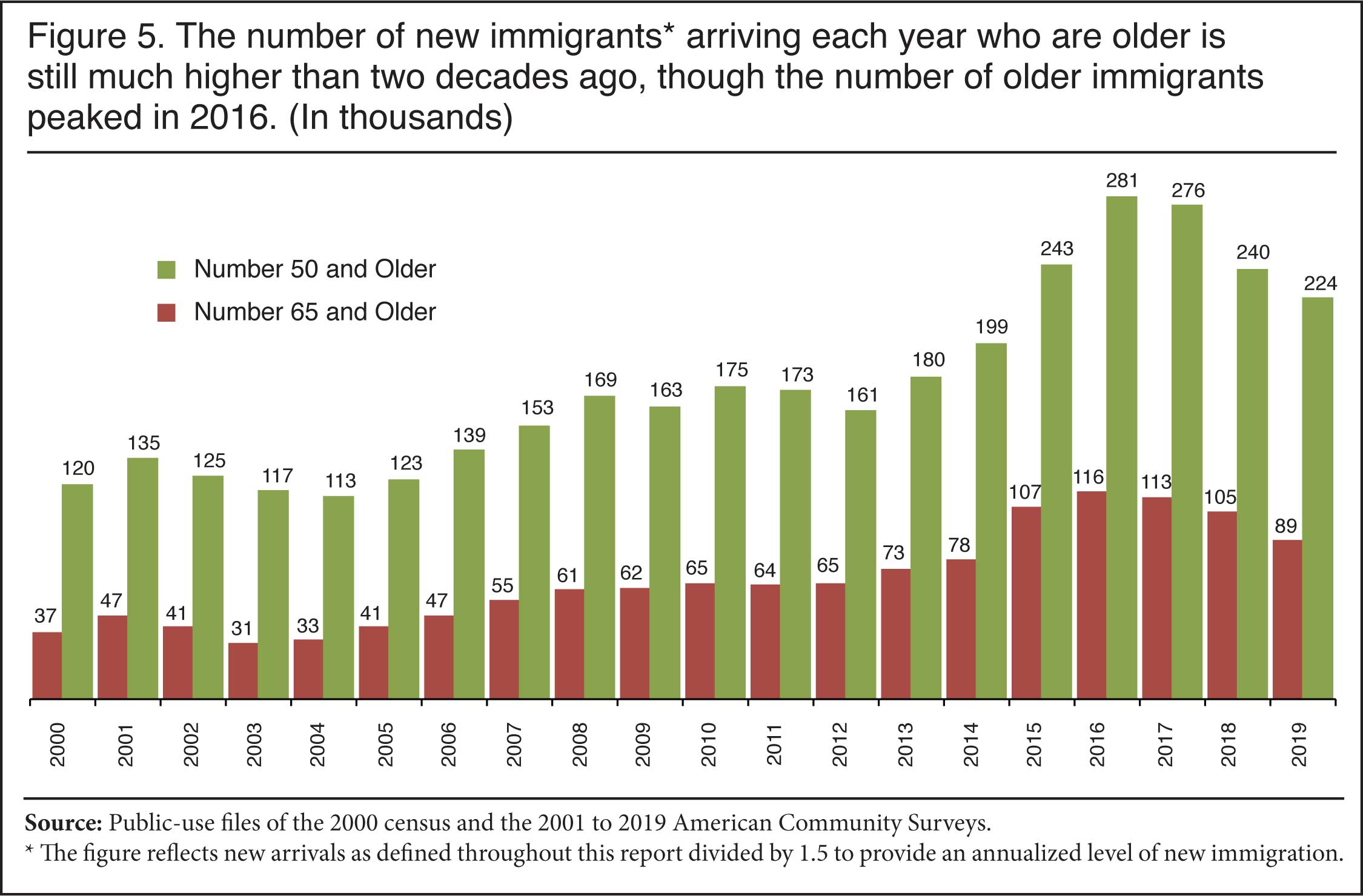

Number of Older Immigrants. The level of immigration has fluctuated in the last two decades. As the Center for Immigration Studies has reported in prior studies, the number of immigrants fell immediately after the Great Recession, then rose significantly, hitting a peak in 2016 and then falling in the first years of the Trump administration.4 With fewer immigrants arriving after 2016, the number of older immigrants entering the country was also down in recent years, yet it remains well above what it was in 2000.

Figure 5 shows that the arrival of older immigrants on an annualized basis increased along with the overall level of newcomers from 2013 to 2016.5 The decline in new immigration after 2016 also caused a decline in the number of older immigrants arriving. Despite the decline in overall immigration and the resulting decline in the number of older newcomers, it is still the case that 224,000 new immigrants settled annually in the country who are age 50 and older, nearly twice what it was in 2000. The number of new immigrants 65 and older coming on an annual basis is more than twice what it was in 2000.

|

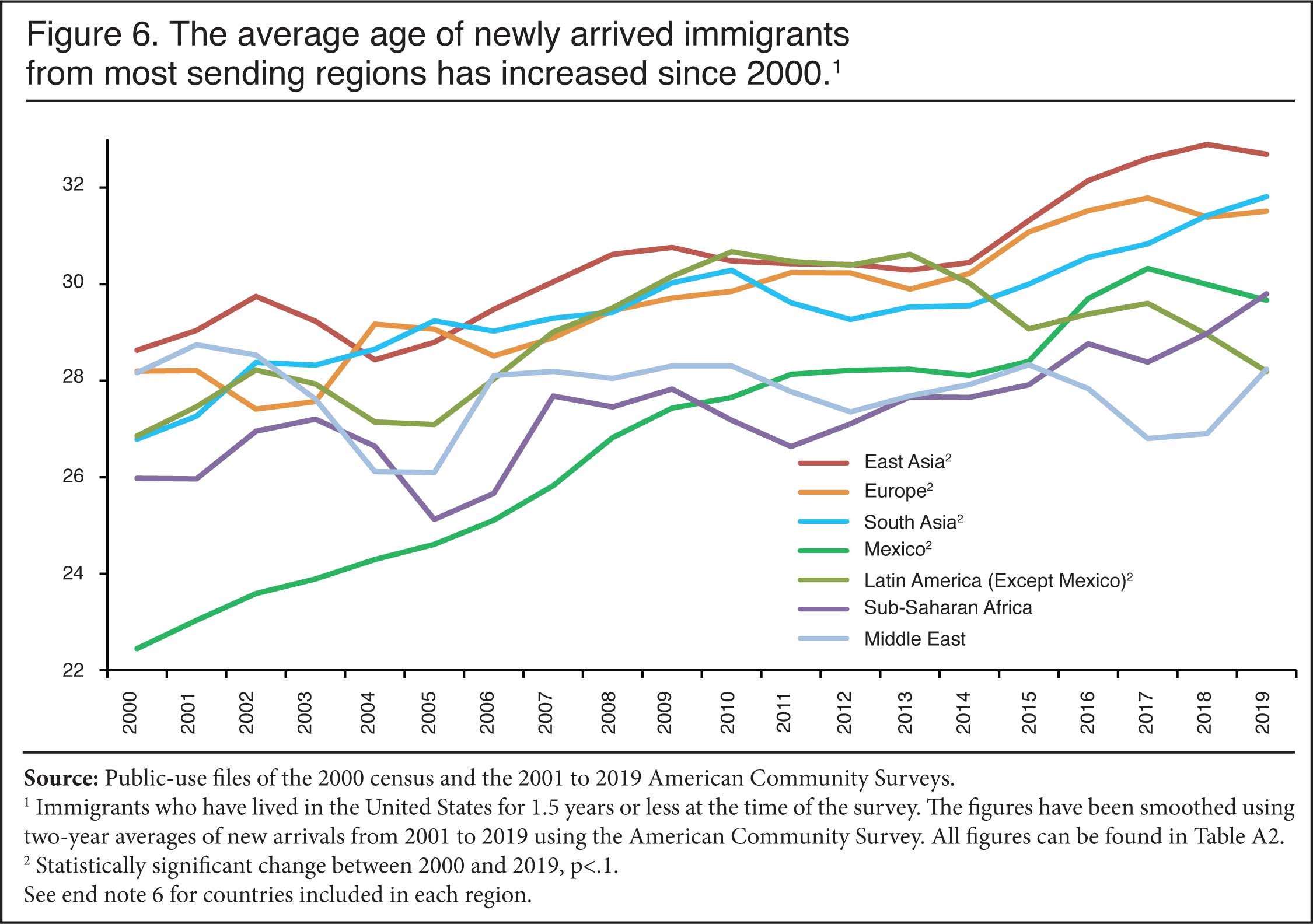

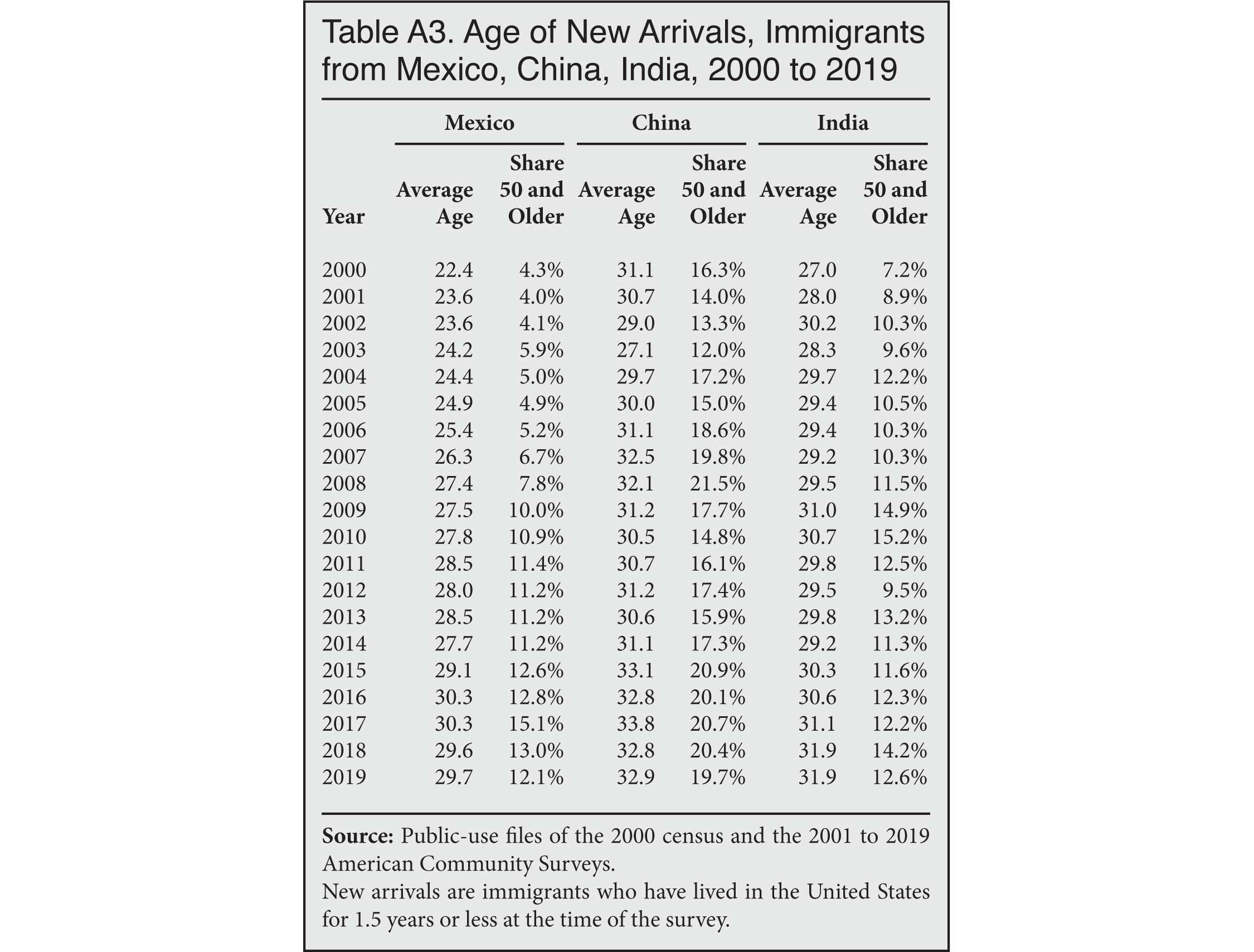

The Rise in Age Is a Broad Phenomenon. Figure 6 reports the average age for immigrants by sending region.6 The figure shows that the increase in the average age of new immigrants from 2000 to 2019 was statistically significant for East Asia, Europe, South Asia, Mexico, and the rest of Latin America. Those regions alone account for 85 percent of new arrivals. Appendix Table A2 reports figures for the average age and share over 50 for each region for new arrivals. Table A3 shows the same information for the top-three sending countries of Mexico, China, and India. (Sample size issues make it more difficult to examine new arrivals from other individual countries that send fewer immigrants than these three countries.) Figure 6 and Tables A2 and A3 indicate that the rise in the age of immigrants is broad, impacting new immigrants from most sending regions. This means the factors causing the increase are not simply confined to immigrants from one country or one part of the world.

|

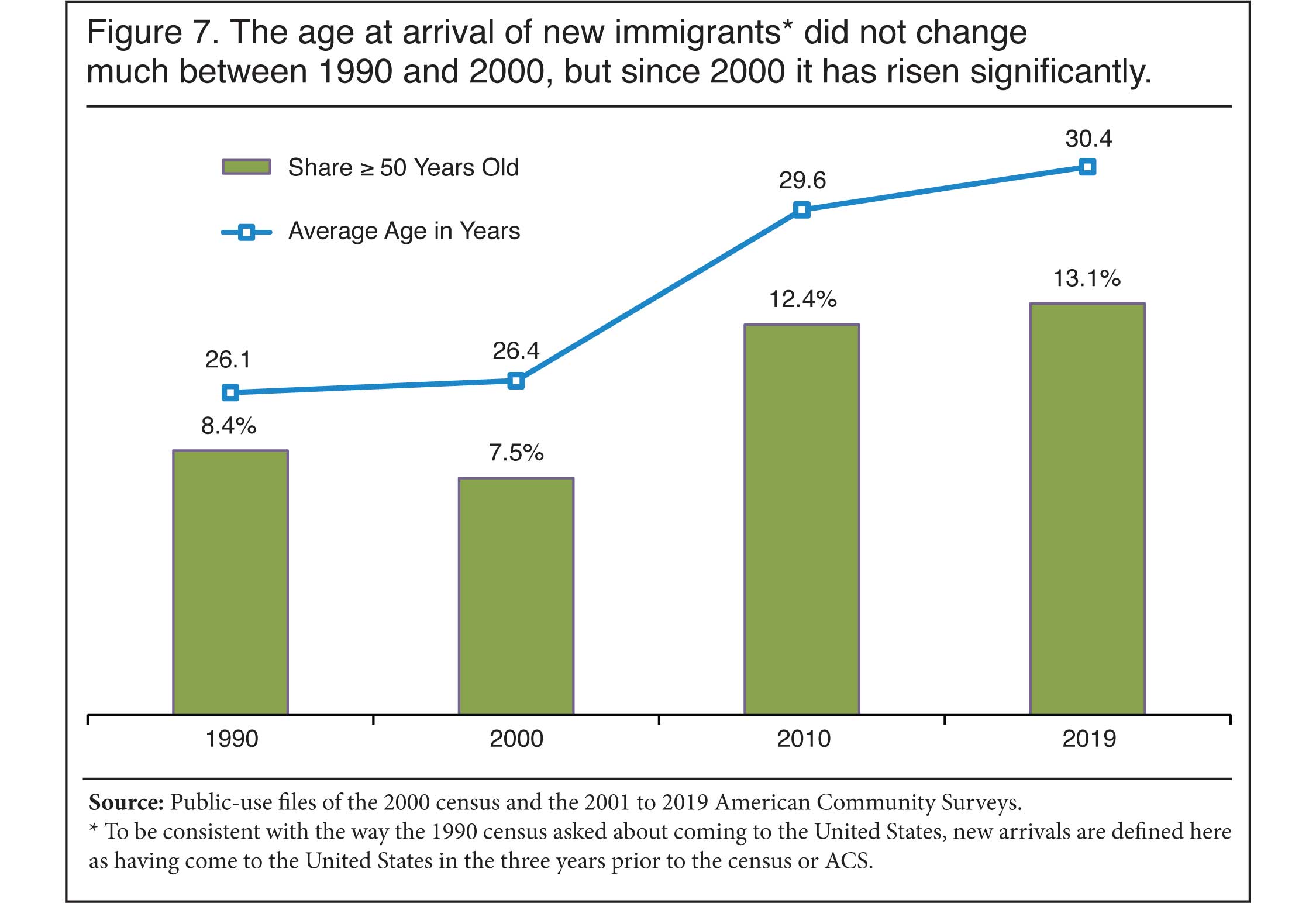

Longer-Term Comparisons. The public-use ACS and the 2000 census files provide single-year-of-arrival data going back to 2000. Prior to 2000, single-year-of-arrival information does not exist in Census Bureau data. The 1990, 1980, and 1970 censuses, for example, all grouped year-of-arrival responses into multi-year cohorts, so data on recent immigrants is not available in the same way before 2000 as it is after 2000. However, it is possible to recode the data after 2000 to match the 1990 census, which grouped arrivals for the census year and the three years prior (1987 to 1990). The 1980 census used a different coding scheme. Figure 7 reports data from 1990 and from later years using a consistent definition of new arrivals. It shows that the age of recent arrivals, defined as those who arrived in the three years prior to the survey or census year, is similar in 1990 and 2000, whereas in the first decade of this century there was a large shift to older ages. Whatever factors caused the age at arrival of new immigrants to increase, it seems to be a post-2000 phenomenon.

|

Causes of Increased Age at Arrival

Aging in Sending Countries. Several factors likely caused the decline in the youthfulness of new immigrants. One is the general aging in all of the primary sending regions and countries. Almost every country in the world has experienced a significant decline in fertility and a rise in life expectancy, referred to by demographers as the "demographic transition". This trend may be more pronounced in Europe, the United States, and parts of East Asia, but as the UN has reported, "The world's population is ageing: virtually every country in the world is experiencing growth in the number and proportion of older persons in their population."7 This increase is expected to continue for the foreseeable future throughout the world. This is certainly true in all of the areas that send the most immigrants to the United States, including Asia and Latin America. If the pool of potential migrants is older in sending countries, then it is likely to impact the age at which people come to the United States. It is worth adding that the aging of the world's population makes it unlikely that the youthfulness of new immigrants to the United States will return to the level in 2000, even if there are some fluctuations in the age at arrival in the future.

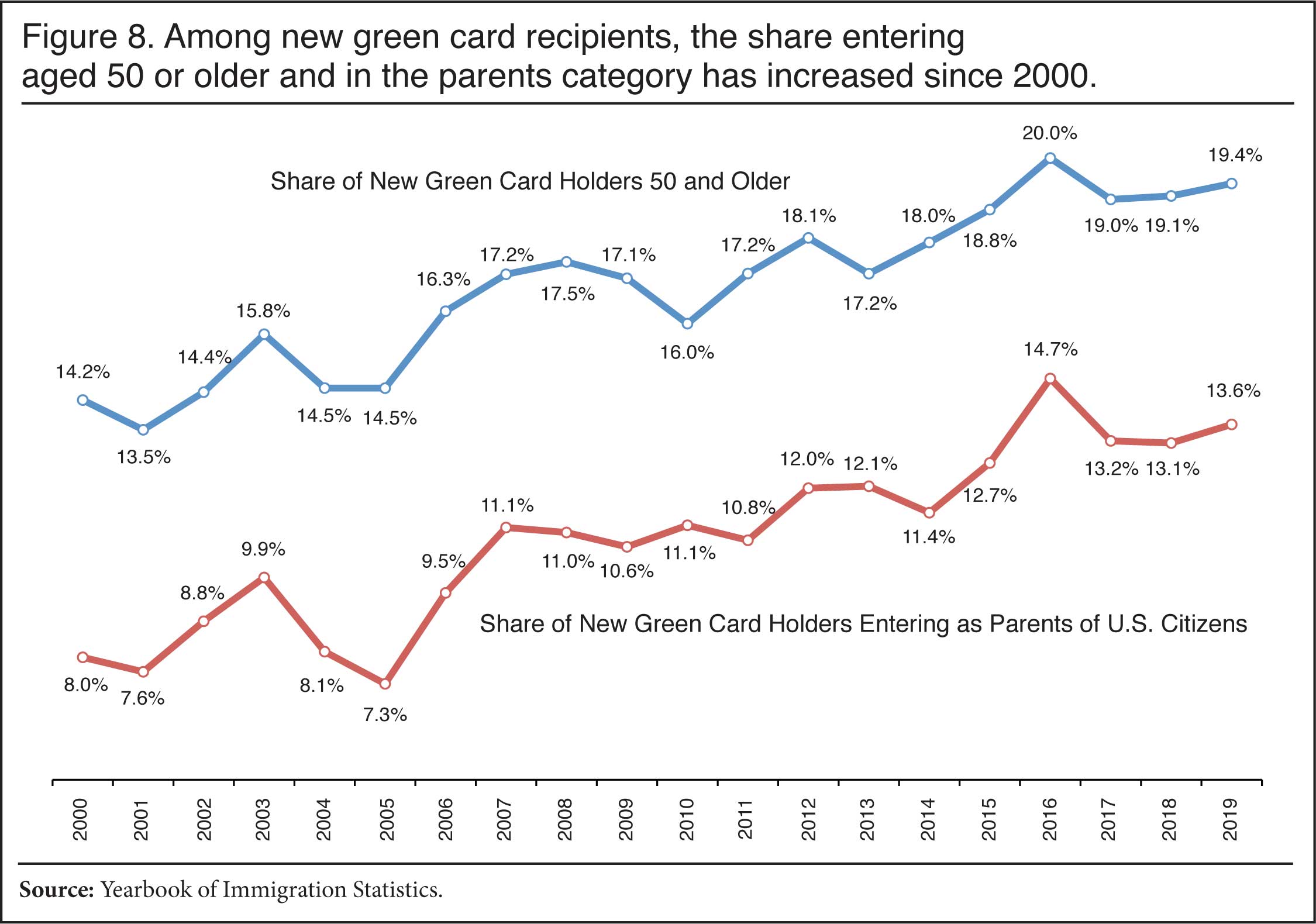

More Parents Getting Green Cards. Family relationships are the primary way persons obtain legal permanent residence in the U.S. This is the so-called "green card". Under current law, American citizens may sponsor their parents overseas for green cards without numerical limit. While legal immigrants typically wait five years before applying for citizenship, between 2000 and 2019, 14.1 million people naturalized.8 This reflects the cumulative effect of several decades of high legal immigration. The number of naturalized citizens increased from 12.5 million in 2000 to 23.1 million in 2019. Nearly 96 percent of these individuals were 21 and older in 2019 and so potentially could sponsor a parent overseas. This means there is an ever-larger pool of people in the United States who can sponsor a parent or parents overseas.

Adult children sponsoring a parent typically came to the United States as adults. If they came as children, more often than not they came with their father or mother and so their parents typically do not need green cards. Because those in the parent category are sponsored by an adult child, the parents are almost always in their late 40s or older when they get their green cards9Figure 8 shows that the share of all new green cards going to parents has increased significantly since 2000. While the administrative data is limited, Figure 8 also shows that the share of new green card recipients 50 and older has risen right along with the increase in the share of green cards going to the parent category.10 The fact that more green cards are going to parents and a larger share of new permanent residents are older almost certainly accounts for a good deal of the increase in the age at arrival of new immigrants.

|

Fall-Off in Illegal Immigration. Illegal immigrants tend to arrive at younger ages, so a decline in new illegal immigrants should increase the average age of all new arrivals in Census Bureau data, which does include them. Robert Warren, formally of the INS and now at the Center for Migration Studies, has done some of the most detailed work on estimating new illegal in- and out-migration. His research shows that the annual number of new illegal immigrants in the 1990s was roughly 800,000 a year, but it was much higher at the end of the decade than at the beginning. He also reports that from 2000 to 2009, the flow of new illegal immigrants arriving into the country also averaged about 800,000, but it was higher in the earlier part of the decade than the end. For the 2010 to 2018 period, he estimates about 600,000 new arrivals per year, with some fluctuation during the decade.11 If Warren is correct and the number of new illegal immigrants was highest around 2000, while it fell significantly by 2009 and has remained lower, then it could help to explain the rise in the age of new immigrants. To be clear, changes in the size of the total population of illegal immigrants are not the same as new arrivals. In addition to newcomers, the size of the total illegal population is impacted by deportations, voluntary return migration, those who obtain legal status, and deaths.

Mexico has traditionally been the top sending country for illegal immigrants; a decline in people coming illegally from that country should cause the age at arrival for that country to increase significantly. The dramatic increase in the age of newly arrived Mexican immigrants shown in Figure 6 and Table A3 is a good indication that the decline of illegal immigration explains in part the rise in the age of new immigrants. However, Figure 6 and Table A2 also indicate that even new immigrants from regions such as South Asia, East Asia, and Europe, from which relatively fewer illegal immigrants have traditionally come, also exhibit a marked increase in age at arrival. Further, the increase in the absolute number of older immigrants compared to 2000 — not just the percentage of new arrivals — shown in Figure 5, cannot be explained by the decline in new illegal immigrants. So while the decline in illegal immigration almost certainly accounts for some of the rising age of new immigrants, other factors are clearly contributing to the trend.

Implications

Impact on the Aging of American Society. One of the most common arguments made about immigration is that it prevents post-industrial societies with low fertility and high life expectancy from aging. The younger the immigrants are at arrival, the larger their positive impact on aging in the receiving society. In reality, there is general agreement among demographers that while immigration makes the population much larger, its impact on slowing the aging of low fertility countries like the United States is modest.12 The significant increase in the age at which immigrants are coming to America shown in this report means that the modest positive impact on the nation's age structure will be correspondingly smaller moving forward.

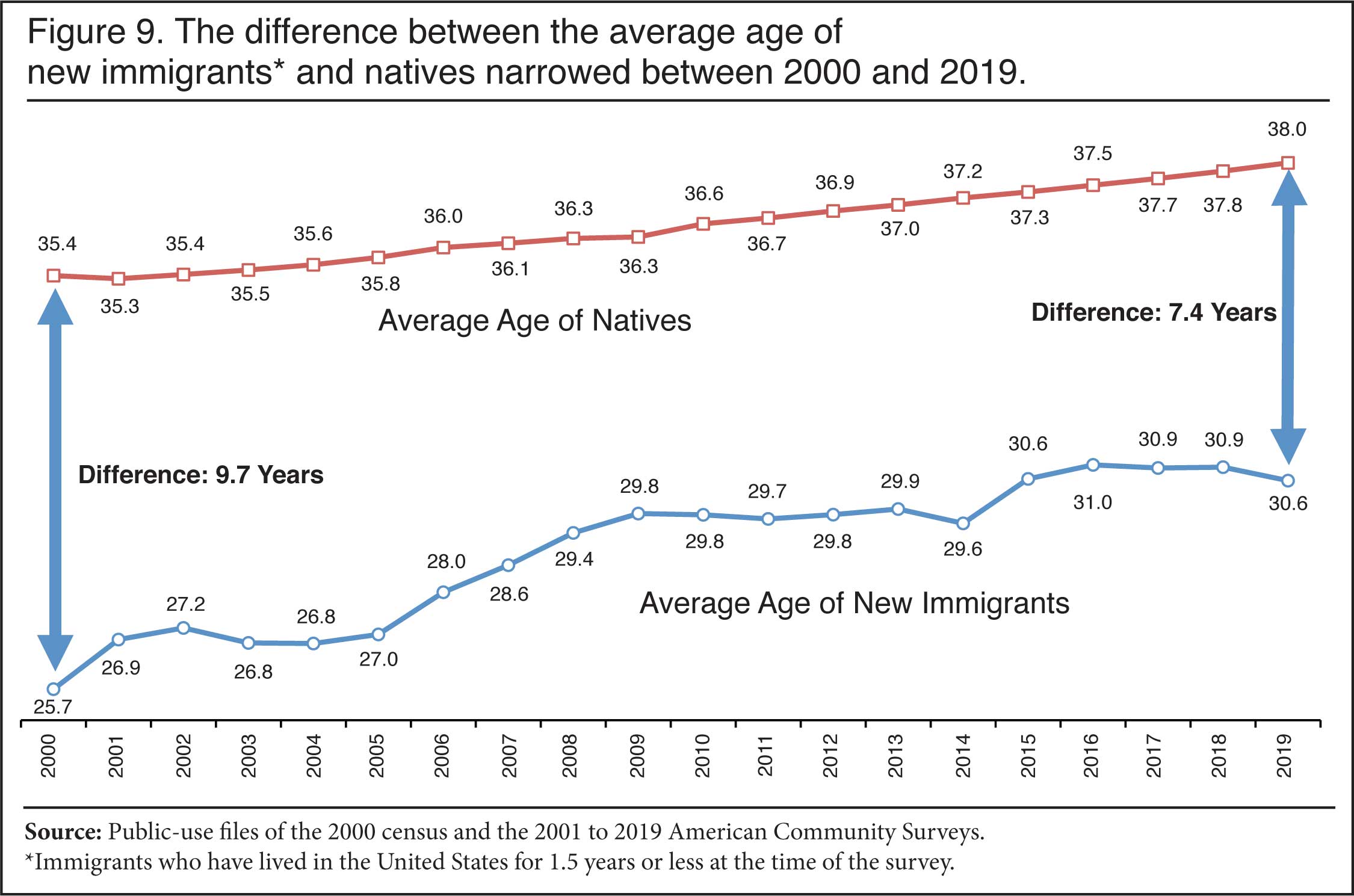

One way to think about this question is that the larger the difference in the average age of new immigrants relative to the average age of the existing native population, the more immigration will lower the average age of the country. Other factors like fertility and life expectancy also matter. Figure 9 shows the average age of immigrants at arrival relative to the average age of all natives. In 2000, new immigrants were 9.7 years younger than the average native-born person. In 2019, the average age of natives had risen, but not as fast as the average age of new arrivals, so that the difference was 7.4 years.

|

We can also gain insight into the effect of immigration on age by comparing the effect of immigrants in 2000 to those in 2019. While the effect of one year of immigration on the average age in the United States is so small it is difficult to measure, we can examine the effect of immigration over the course of several years. In 2000, the average age in the United States was 35.8 years; if we exclude those immigrants who came in the prior five years, the average age would have been 36.04 years — a reduction in average age of 0.24 years. In 2019, immigrants who had arrived in the prior five years lowered the average age in the United States by only .19 years. The rise in the age at arrival of new immigrants means that the immediate impact of immigration on the nation's age structure is now smaller than it was two decades ago, at least in the short term.13

Fiscal Implications of Older Immigrants. A number of studies have examined the taxes paid and costs created by immigrants in order to discern their net fiscal impact. The National Academies of Sciences, Engineering, and Medicine (NAS) has done some of the most extensive research in this area. One of the conclusions of NAS studies in both 1997 and 2017 was that immigrant age at arrival is one of the key factors determining their net lifetime fiscal impact. Education level is another key factor. As the 1997 NAS study observed, "the fiscal impact of an immigrant depends heavily indeed on the immigrant's age and education at arrival."14

The 2017 NAS study also showed that younger arrivals often have a more positive impact than older arrivals. The study did not report the lifetime net fiscal impact of immigrants by detailed age groups. But it did provide estimates for those who arrived aged 0-24, 25 to 64, and 65 and older. The 2017 NAS study included eight different fiscal scenarios based on different assumptions about future taxes and expenditures. The analysis shows that the original immigrant is a net fiscal positive in all eight scenarios if he came between the ages of 0 and 24, paying more in taxes than costs created during his lifetime, regardless of education level. Those who arrived ages 25 to 64, were a fiscal benefit in five of the eight scenarios; and, those who came over age 64 were an unambiguous net drain in every scenario. None of this is surprising; those who come at older ages typically have fewer working years to pay taxes before they retire and are drawing on entitlements for the elderly.15

In addition to the NAS studies, we can see the likely negative fiscal implications of immigrants who arrive at older ages by looking at the 2019 ACS data. The survey from 2019 shows that, for immigrants who were 65 and older and had come in the five years prior, 27 percent were on Medicaid (the health insurance program for the poor) compared to 13 percent for the native-born in this age group. The vast majority of these immigrants had not been in the country long enough to pay into Medicare (the insurance program for the elderly) to be eligible for that program, but because many of them have low incomes, they access Medicaid at very high rates. Data from the Census Bureau's Current Population Survey Annual Social and Economic Supplement from 2019 shows that about 15 percent of immigrants 65 and older who came to the United States in the prior five years accessed the Supplemental Security Income (SSI) program — seven times the 2 percent of native-born Americans age 65 and older. The program provides cash payments to the disabled and low-income elderly.

The above figures are a good reminder that immigrants who arrive at older ages often struggle to support themselves and even if they may not be eligible for Medicare or Social Security, having not paid into those programs long enough or at all, they still often access programs like Medicaid and SSI at high rates. All of this means that the increase in the age at arrival of immigrants likely has negative fiscal implications, especially the significant increase in the number of immigrants coming in the oldest age groups.

Aging Among All Immigrants

There is no question that immigrants are coming to America at older ages. However, at any given moment new immigrants account for only a modest share of all immigrants. In 2019, there were 44.9 million immigrants (legal and illegal) in the country. Like all people over time, the existing immigrant population ages. Of course, new immigrants will make the overall immigrant population somewhat younger when they first arrive, though how much younger depends on their age and number. Since new immigrants are coming at older ages than in the past, this will tend to reduce their ability to slow the aging of the nation's overall population or slow the aging of the overall immigrant population.

Interestingly, between 1990 and 2000, the share of all immigrants 65 and older actually fell. This was partly due to the relatively large number of all immigrants who were elderly in 1990, which reflected the large flows of immigration earlier in the century, including the tail end of the Great Wave, which ended in the early 1920s. By 2000, many of these very old immigrants had passed away, making the overall immigrant population younger in 2000 than it was in 1990. As we have seen, since 2000 immigrants have been arriving at older ages and, as the next section will show, the overall immigrant population has aged significantly in the last two decades.

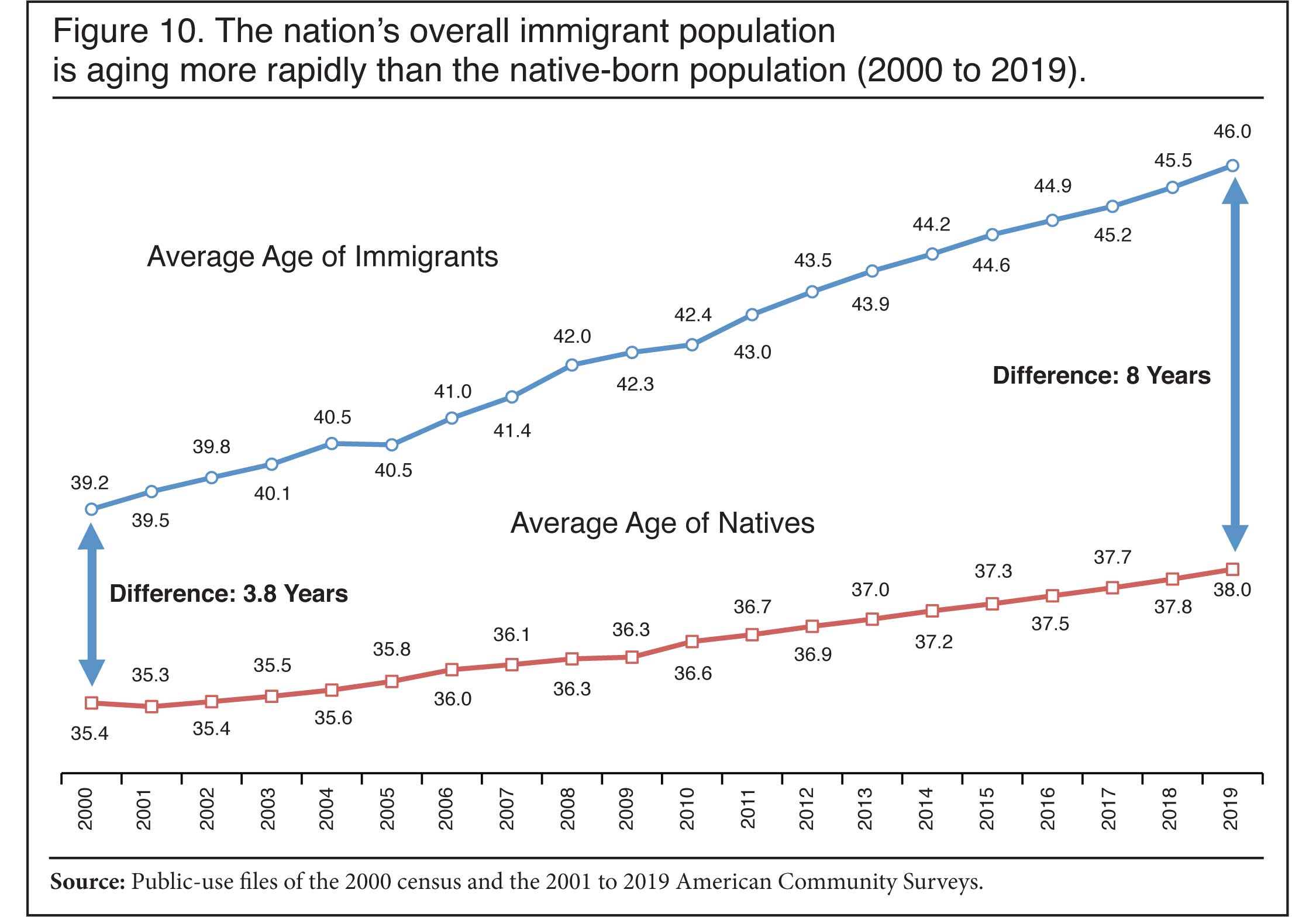

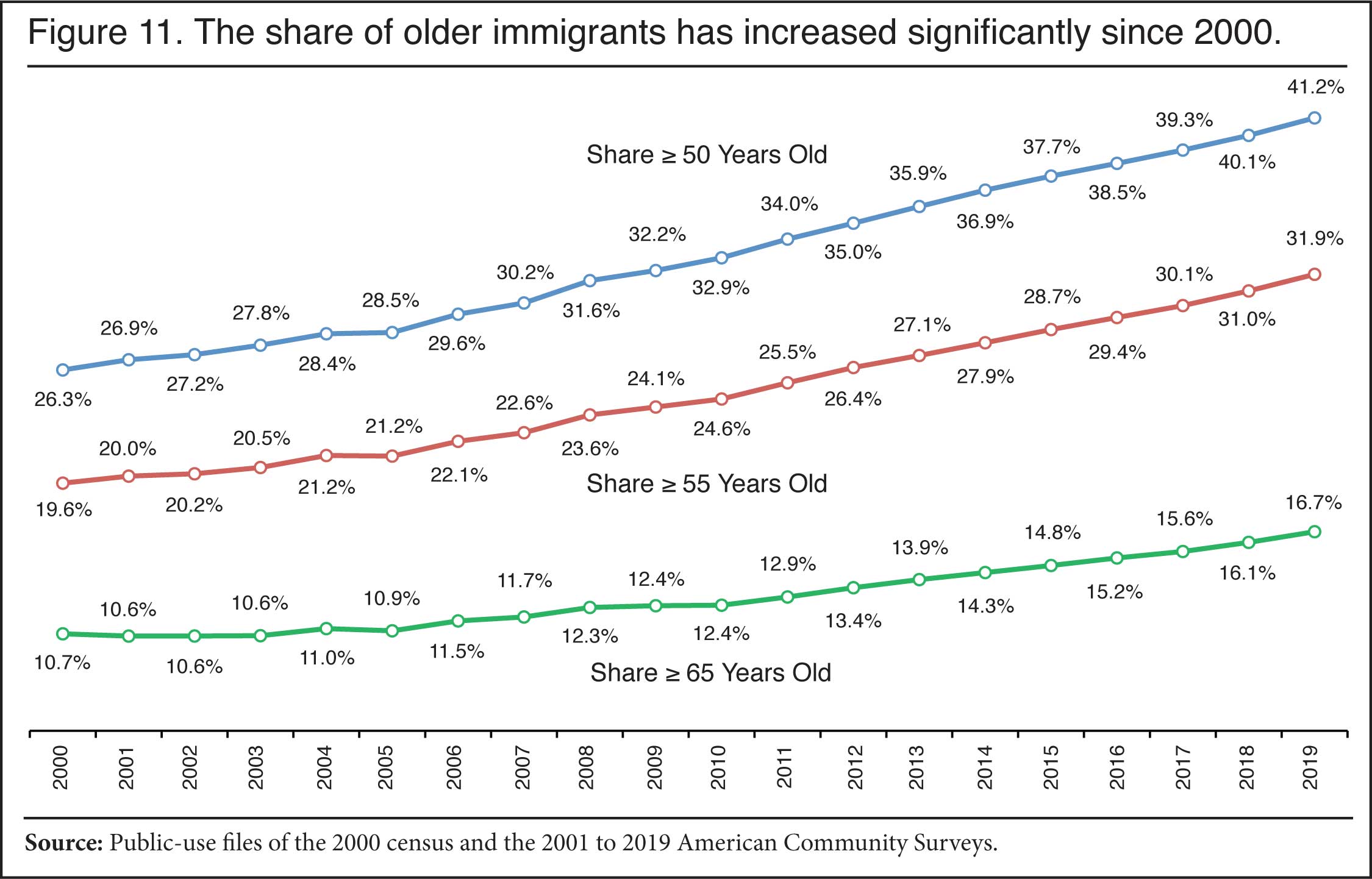

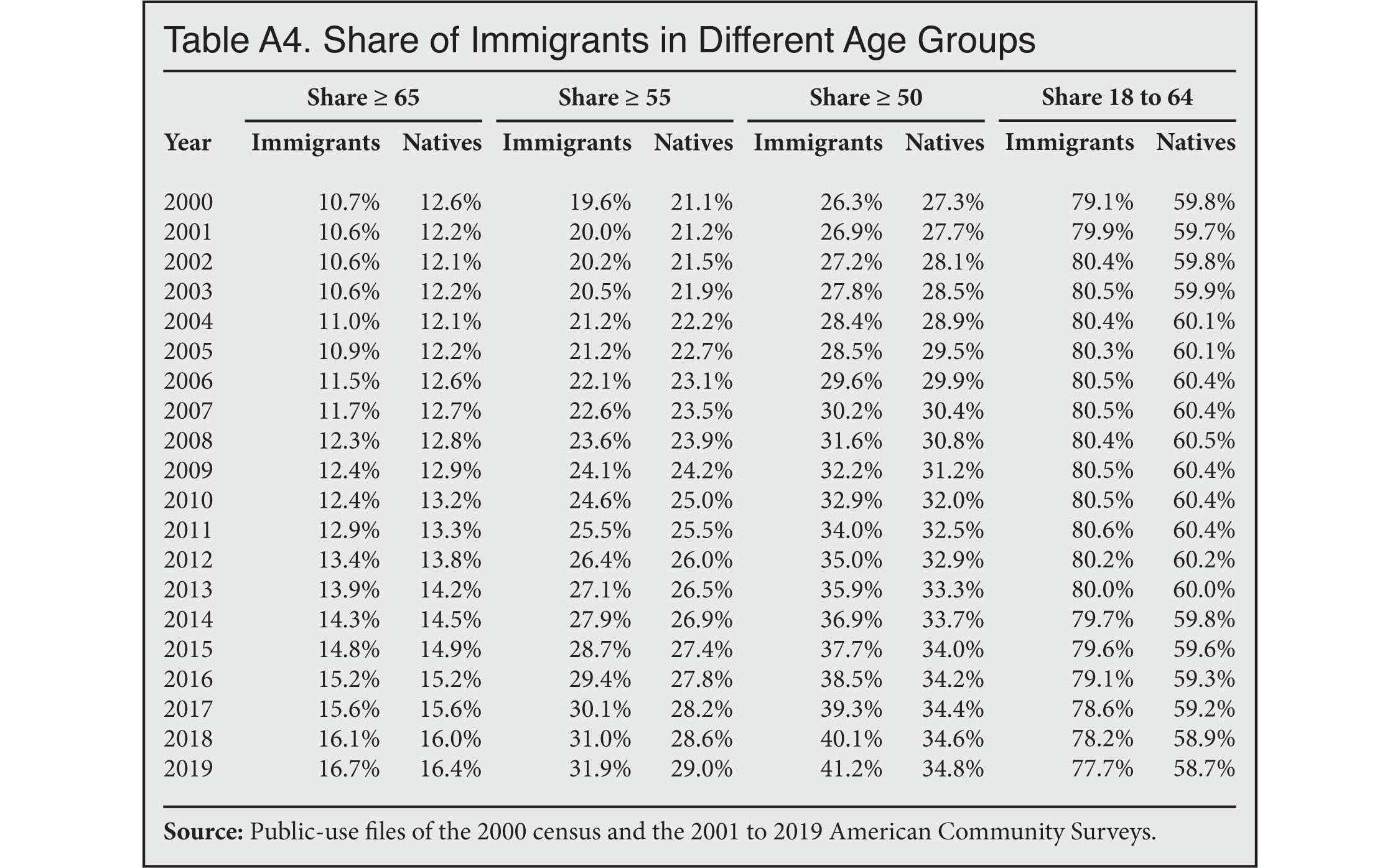

The Increasing Age of all Immigrants. Figure 10 shows the average age of all immigrants — newcomers and established immigrants — relative to the native-born. It is similar to Figure 9, except that Figure 10 is a comparison between all immigrants and natives, rather than only new immigrants, as shown in the prior figure. The average age of all immigrants has increased significantly, from 39.2 years in 2000 to 46 years in 2019, or about 2.5 times more than the average age of the native-born. Figure 11 shows the percentage of all immigrants who are 50 and older, 55 and older, and 65 and older. The older age groups experienced dramatic growth since 2000.16 Figure 12 shows the percentage increase in the number of immigrants in each age group. Probably the most striking thing in Figure 12 is that the number of immigrants who are of working-age grew by 42 percent between 2000 and 2019; however, the number 65 and older grew by 126 percent.17 It cannot be overemphasized that immigration does not simply add to the population of potential workers, it also adds to the older population.

|

|

|

Immigrants as a Share of Older Americans. Population aging among immigrants can also be seen by looking at the share of all persons in older age groups who are immigrants. Figure 13 reports the share of each age group in the United States who are immigrants, not the share of immigrants in these age groups. So Figure 13 reads as follows: In 2000, 9.5 percent of all persons in the country 65 and older were immigrants and by 2019 it was 13.9 percent. In fact, the immigrant share of the elderly now slightly exceeds their share of the total population. This simply reflects the fact that the nation's immigrant population is aging rapidly.

|

Births Do Not Add to the Immigrant Population. When thinking about immigration and the aging of American society, it is important to keep in mind that births within the United States to immigrants do not add to the immigrant population, but instead are added to the native-born population. This makes the native population more youthful while the lack of births to immigrants is part of the reason the immigrant population ages so quickly. This means it is not enough to simply look at immigrants when thinking about the total long-term impact of immigration on the aging of the U.S. population.

Immigrants have descendants who have to be fully accounted for when examining the totality of immigration's impact on the nation's age structure. Of course, the prior research cited at the outset of this report and in end note 1, as well as projections by the Census Bureau and the Center for Immigration Studies, all take into account immigrants and all of their progeny. The research is clear: Immigration (immigrants and all their descendants) can make for a significantly larger population, but not a significantly younger population. As Figures 10 through 13 (and appendix Tables A4 and A5) make clear, immigrants do not simply add potential workers. As we have seen, immigrants arrive at all ages, and they age over time. Moreover, immigrants are now arriving at older ages compared to newcomers in previous years. These simple facts are often overlooked by those who think of immigrants only as young workers, rather than as human beings who are spread across the age distribution at arrival and then age over time.

It is worth adding that in a recent report by the Center, we detailed the very significant decline in immigrant fertility over the last two decades.18 In 2019, the fertility of immigrants dropped below replacement level (2.1 children per women on average) for the first time. The difference between immigrant and native fertility has narrowed significantly. Like the increase in age at arrival, the decline in immigrant fertility further reduces the ability of immigration to slow the aging of American society.

Conclusion

The fact that immigrants are coming at older ages not only reduces their already small positive impact on the age structure of the U.S. population, it also has negative fiscal implications. Research by the National Academies for Sciences, Engineering, and Medicine indicates that immigrants who arrive at older ages tend to create a net fiscal drain, creating more costs for the government than they pay in taxes. Because immigrants are now arriving at older ages, including many at or near retirement, it means that the fiscal impact of immigration will be more negative or at least less positive than would have been the case had the average age of immigrants remained younger.

This analysis also includes a brief look at the aging of immigrants generally. The findings make clear that the average age and the share of all immigrants who are in older age cohorts have increased significantly in recent years. For example, the number of working-age immigrants grew by 42 percent between 2000 and 2019, but the number 65 and over increased by 126 percent. While calculations of this kind do not include births to immigrants and so do not represent a full accounting of the total impact of immigration on the age of the U.S. population, they are a powerful reminder of how immigration adds to both the working-age and the population of retirees.

The natural aging of immigrants already in the country will certainly continue. In contrast, the age at which immigrants arrive could change if, for example, the selection criteria for new legal immigrants are altered, illegal immigration increases or decreases, or if other factors play a role. The modest fall in the age at arrival in 2018 and 2019 is an indication that the age profile of newcomers can change, at least modestly. But the general aging of populations in all of the primary sending regions, and the increase in age of immigrants already in the country, who sponsor most of the family members admitted under the legal immigration system, make it very unlikely that newly arrived immigrants would ever return to the more youthful profile of the past. This means that any effort to understand the impact of immigration on American society in the future will need to take into account the profound change in the age composition of new immigrants into the United States.

Appendix

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

End Notes

1 In a 1992 article in Demography, the leading academic journal in the field, economist Carl Schmertmann explained that, mathematically, "constant inflows of immigrants, even at relatively young ages, do not necessarily rejuvenate low-fertility populations. In fact, immigration may even contribute to population aging." A UN study two decades ago also found that immigration alone cannot make up for population decline and aging in Western countries. The Census Bureau also concluded in 2000 that immigration is a "highly inefficient" means for increasing the percentage of the population that is of working-age in the long run. See Carl P. Schmertmann, "Immigrants' Ages and the Structure of Stationary Populations with Below-Replacement Fertility", Demography, Vol. 29, No. 4, November 1992, and "Replacement Migration: Is It a Solution to Declining and Ageing Populations?" , United Nations Department of Economic and Social Affairs, Population Division, March 2000. The 2000 Census Bureau population projections can be found here. The Center for Immigration Studies' most recent population projections based on Census Bureau projections also show the modest impact of immigration on population aging. See Steven A. Camarota and Karen Zeigler, "Projecting the Impact of Immigration on the U.S. Population: A look at size and age structure through 2060", Center for Immigration Studies Backgrounder, February 4, 2019.

In February 2020 the Census Bureau added immigration scenarios to its population projections. The Census Bureau's immigration scenarios can be found here. Table B, "Projected Components of Immigration Change", shows net immigration through 2060 under different immigration scenarios. Their low immigration scenario assumes net immigration (the difference between the number of people coming vs. going) will total 27.8 million through 2060. Their high immigration scenario assumes net immigration of 76.9 million by 2060. Table A, "Projected Population Size and Annual Total Population Change" shows the size of the U.S. population under different scenarios. The low immigration scenario produces a U.S. population of 376.2 million in 2060, while the high immigration scenario produces a total population 70.6 million larger of 446.9 million in 2060. These numbers reflect future immigrants and their progeny. The second tab in Table D, "Projected Population by Age Group", reports the share of the population by age cohorts under the different scenarios. Under the low immigration scenario, 56.3 percent of the population will be adults of working age (18-64); under the high immigration scenario, 57.4 percent will be — a 1.1 percentage-point difference. This means the 70.6 million additional people added to the country under the high immigration scenario, relative to the low immigration scenario, increases the working-age share by 1.1 percentage points.

One way to think about this effect is to compare the decline in the working-age share that occurs under the two scenarios. The Census Bureau reports in Table D that, in 2016, the takeoff year for their projections, just slightly under 62 percent of the U.S. population was of working-age. The 2060 working-age share in the low immigration scenario shows a decline of 5.7 percentage points. This compares to a decline of 4.6 percentage points under the high immigration scenario. So about 80 percent of the decline in the working-age share occurs under a high immigration scenario relative to a low immigration scenario even though the high immigration scenario adds nearly 71 million more people to the country.

While the decline in the share of the U.S. population who are of working-age is probably the most important concern when it comes to the aging of American society, the share 65 and older is another common way to think about this issue. Census Bureau Table D shows that the share 65 and older will be 24.3 percent in 2060 under the low immigration scenario compared to 22.3 percent in the high immigration scenario — a two percentage-point difference. Table D also shows that the share in this age group in 2016 was 15.2 percent. This means that under the high immigration scenario, about 78 percent of the increase in the elderly share of the population occurs relative to the low immigration scenario. This is a similar percentage to the impact of high vs. low immigration on the working-age share discussed above.

2 Immigrants or the "foreign-born" in Census Bureau data include naturalized citizens, legal permanent residents (green card holders), long-term temporary visitors (e.g. guestworkers and foreign students), illegal aliens, and any other non-citizens captured in the ACS.

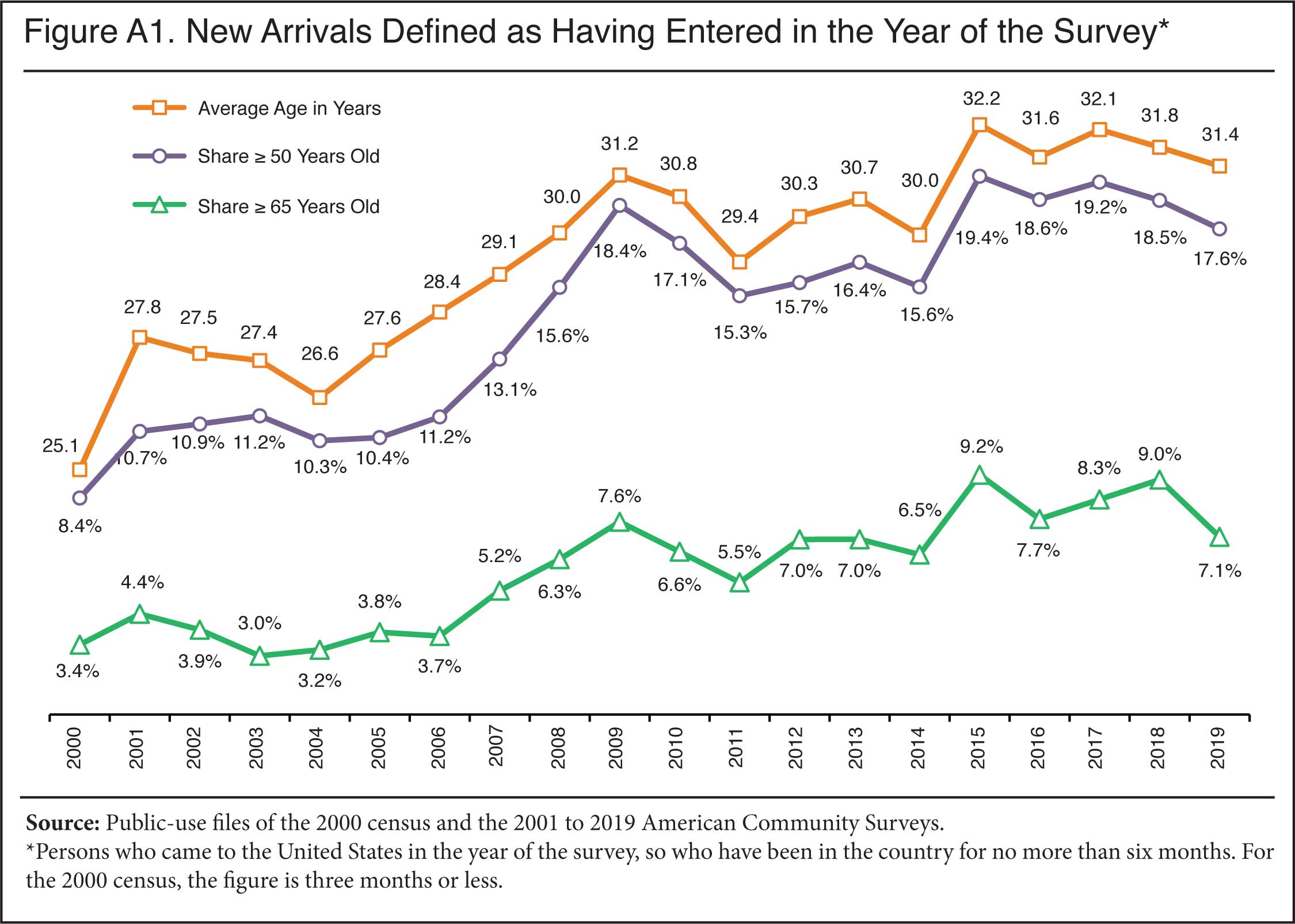

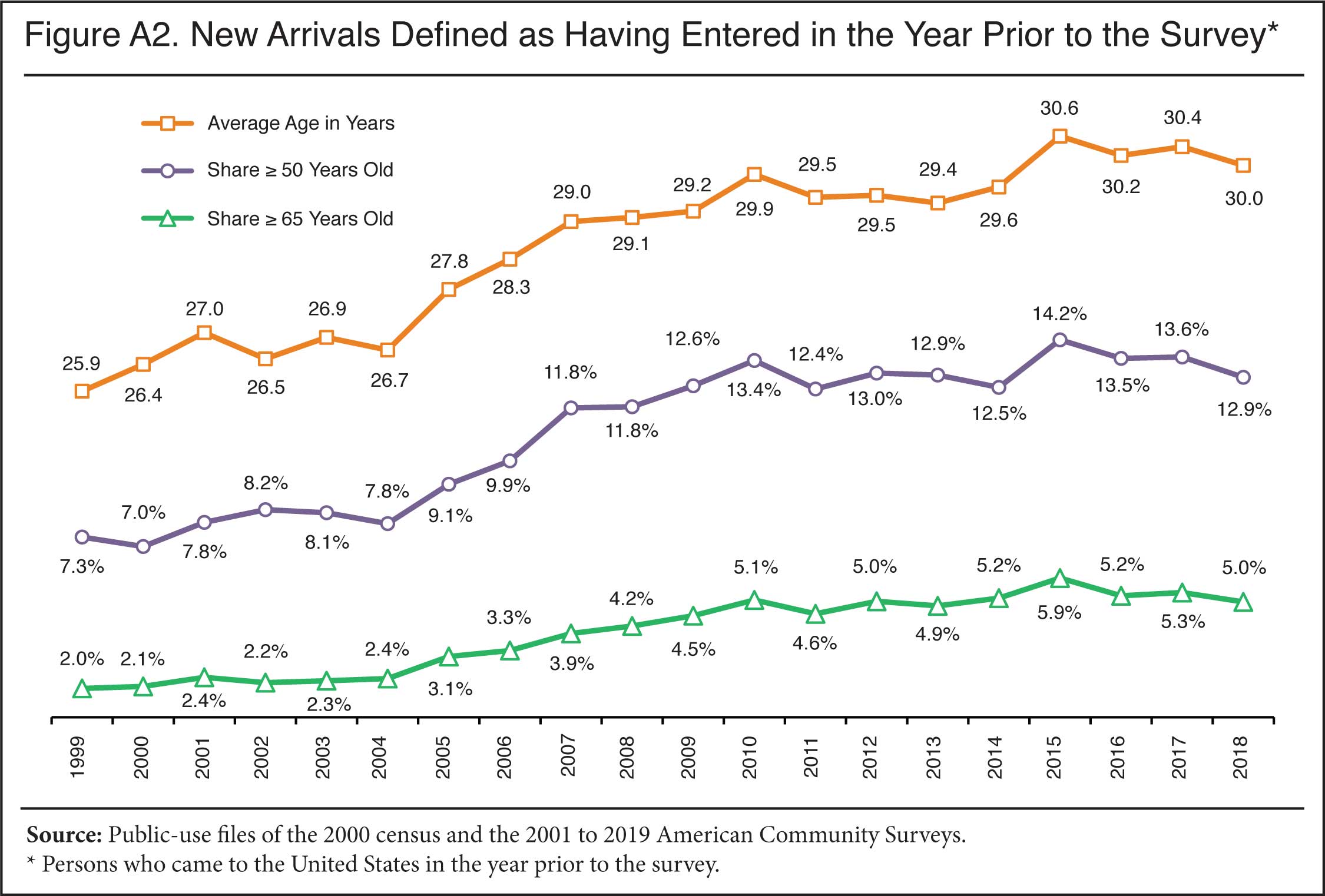

3 Figure A1 in the appendix reports the average age, share 50 and older, and share 65 and older for only those who arrived in the same calendar year as the survey. So data for 2019 in Figure A1 represents new immigrants who came to the United States from January 1 to July 1, 2019, data for 2018 represents those who came in the first half of that year, and so on. (Methodological note: The ACS is collected throughout the year but is weighted to reflect the population at mid-year, so, in effect, the arrival data is for the first half of the year in which it was collected.) Figure A1 shows the same trends as Figure 1, though the fluctuations year to year are somewhat more pronounced than in Figure 1. However, defining new arrivals this way has the disadvantage of not representing a full year of arrival data. It also means the sample size is much smaller than when new arrivals are defined as having come in the prior 1.5 years (as in the other figures in this report), making for less robust estimates. Figure A2 shows age at arrival when new arrivals are defined as having come in the calendar year prior to the survey, so the percentages for 2018 are from the 2019 ACS and those for 2017 are from the 2018 ACS and so on. Those who arrived in the first half of the year in which the survey took place are excluded in Figure A2. Like Figure A1, Figure A2 shows the same basic pattern as found elsewhere in this report: New immigrants are coming to America at older ages. Defining new arrivals as having come in the prior calendar year allows us to examine one year at a time, but no figures are possible for 2019 because there is only half a year of data available for that year. Also, the sample size is one-third smaller than when we define new arrivals as those in the country for 1.5 years. For these reasons, we define new immigrants as having come to the United States in the year of the survey or the prior year throughout this report. But as Figures A1 and A2 make clear, defining new arrivals differently does not fundamentally change our findings — immigrants are coming to America at older ages than was the case in the recent past.

4 Steven A. Camarota and Karen Zeigler, "New Census Bureau Data Indicates There Was a Large Increase in Out-Migration in the First Part of the Trump Administration", Center for Immigration Studies Backgrounder, October 22, 2020.

5 As already indicated, in this analysis new arrivals are defined as having lived in the country for 1.5 years or less at the time of the survey or 2000 census. The figures reported in Figure 5 reflect the number of new arrivals divided by 1.5 to provide an annualized level of new immigration.

6 Regions are defined in the following manner: East Asia: China (including Hong Kong and Taiwan), Japan, Korea, Cambodia, Indonesia, Laos, Malaysia, Mongolia, Myanmar, Philippines, Singapore, Thailand, Vietnam, Other Southeastern Asia, Other Eastern Asia, Asia n.e.c. South Asia: Bangladesh, Bhutan, India, Nepal, Pakistan, Sri Lanka. Caribbean: Antigua-Barbuda, Bahamas, Barbados, Bermuda, Cuba, Dominica, Dominican Republic, Grenada, Haiti, Jamaica, St. Vincent and the Grenadines, St. Kitts-Nevis, St, Lucia, Trinidad and Tobago, West Indies, Other Caribbean, Other Northern America. Central America: Belize, Costa Rica, El Salvador, Guatemala, Honduras, Nicaragua, Panama, Other Central America. South America: Argentina, Bolivia, Brazil, Chile, Colombia, Ecuador, Guyana, Paraguay, Peru, Uruguay, Venezuela, Other South America. Middle East: Afghanistan, Azerbaijan, Iran, Kazakhstan, Uzbekistan, Iraq, Israel, Jordan, Kuwait, Lebanon, Saudi Arabia, Syria, Yemen, Turkey, United Arab Emirates, Algeria, Egypt, Libya, Morocco, Sudan, Tunisia, Other Northern Africa, Other South Central Asia, Other Western Asia. Europe: Denmark, Finland, Iceland, Norway, Sweden, England, Scotland, Ireland, Northern Ireland, Belgium, France, Netherlands, Switzerland, Albania, Greece, Macedonia, Italy, Portugal, Azores, Spain, Austria, Bulgaria, Czechoslovakia, Slovakia, Czech Republic, Germany, Hungary, Poland, Romania, Yugoslavia, Croatia, Montenegro, Serbia, Bosnia, Kosovo, Latvia, Lithuania, Other USSR/Russia, Byelorussia, Moldavia, Ukraine, Armenia, Republic of Georgia, Other Northern Europe, Other Western Europe, Other Southern Europe, Other Eastern Europe, Europe, n.e.c. Sub-Saharan Africa: Eritrea, South Sudan, Cameroon, Congo, Zaire, South Africa, Ethiopia, Kenya, Rwanda, Somalia, Tanzania, Uganda, Zambia, Zimbabwe, Cape Verde, Gambia, Ghana, Guinea, Ivory Coast, Liberia, Nigeria, Senegal, Sierra Leone, Togo, Other Eastern Africa, Other Southern Africa, Other Western Africa, Other Middle Africa, Africa n.e.c. Oceania/Elsewhere: Australia, Oceania, Pacific Islands, Fiji, and elsewhere.

7 See "World Population Ageing 2015", United Nations, Department of Economic and Social Affairs, Population Division, 2015. Between 2010 and 2019, about three-fourths of new arrivals came from South Asia, East Asia or Latin America.

8 See Table 20 in the 2019 Yearbook of Immigration Statistics.

9 If a person arrived as a child and has now reached age 21, then typically, though not always, the whole family, including the parents, would have gotten green cards together so there would be no need for the adult child to sponsor the parents. If, on the other hand, a person is sponsoring a parent they almost always came as adults themselves, naturalized, and then would sponsor parents overseas. This all takes time and, as a result, parents almost always arrive later in life. It is true that the U.S.-born children of illegal immigrants can sponsor their parents once the children reach 21. However, for U.S.-born children to sponsor an illegal immigrant parent, it typically requires applicants to obtain waivers and for the parent to apply from a consulate in their home country during the process. All of this makes it a difficult process. None of the parents adjusting status should show up in the data as new arrivals because, in general, they have lived in the United States for at least 21 years if they have a U.S.-born child that age.

10 Yearbook of Immigration Statistics, Department of Homeland Security.

11 See Robert Warren, "Reverse Migration to Mexico Led to US Undocumented Population Decline: 2010 to 2018", Journal on Migration and Human Security, Vol. 8(1) 32-41, 2020; and Robert Warren and John Robert Warren, "Unauthorized Immigration to the United States: Annual Estimates and Components of Change, by State, 1990 to 2010", International Migration Review, June 2013.

12 See end note 1.

13 It should be noted that there were 7.6 million immigrants who arrived in the five years prior to 2000 — 1995 to 2000. In 2019, there were 7.5 million immigrants who came in the prior five years. While the size of the five-year cohort was similar in both time periods, in 2000 they represented a larger share of the overall population because the overall population was smaller. In 2000, these newcomers accounted for 2.7 percent of the population, compared to 2.3 percent in 2019. This means that part of the reason that the effect was smaller in 2019 is that the newcomers were a smaller fraction of the total population, which had grown in the intervening 19 years. However, if we re-weight the data and assume that those who came in the five years prior to 2019 were also 2.7 percent of the population and still had the same average age, then the new immigrants would have reduced the average age by 0.22 years, still less than the 0.24 years in 2000. One reason for this is that the average age of new immigrants was higher in 2019, so their effect is smaller even if they had been the same share of the overall population as in 2000.

14 See p. 329 in Francine D. Blau and Christopher Mackie, Eds., The Economic and Fiscal Consequences of Immigration, Washington, D.C.: National Academies of Sciences, Engineering, and Medicine, 2017.

15 Table 8-12 (p. 430) in the 2017 National Academies' online version of its report, which can be downloaded here, presents the key findings. The shaded row at the bottom of each fiscal scenario in the table shows the net fiscal impact for each age group, not controlling for education level. The results on the left of the table are the net fiscal impacts for immigrants plus their dependents, while the results in the center of the table report the net impact on public coffers for only the original immigrants. It should be noted that those who arrived after age 64 are assumed to have no U.S.-born descendants in the United States.

16 Table A4 in the appendix shows in detail the share of immigrants and natives who are working-age and in older age groups. Table A5 shows the number of immigrants who are working-age and in older age groups. In Table A5, the number of natives 65 and older drops between 2000 to 2001 and stays lower until 2006. The reason for this is that the ACS did not include those in institutions, which includes nursing homes, until 2006. This impacts the total for natives 65-plus in the table. It has a much smaller impact on immigrants in this age group because a smaller share of immigrants lives in institutions. In terms of the recent arrivals in this report, very few recent immigrants are in institutions, so the addition of the institutionalized in 2006 makes very little difference to our findings. Further, the 2000 census did include the institutionalized, so the data from 2000 and from 2006 to 2019 reported in the figures in this report all include those in nursing homes.

17 In 2000, there were 24.53 million immigrants 18 to 64 compared to 34.79 million in 2019. The number of immigrants 65 and older was 3.32 million in 2000 and 7.5 million in 2019.

18 Steven A. Camarota and Karen Zeigler, "Fertility Among Immigrants and Native-Born Americans: Difference between the foreign-born and the native-born continues to narrow", Center for Immigration Studies Backgrounder, February 16, 2021.