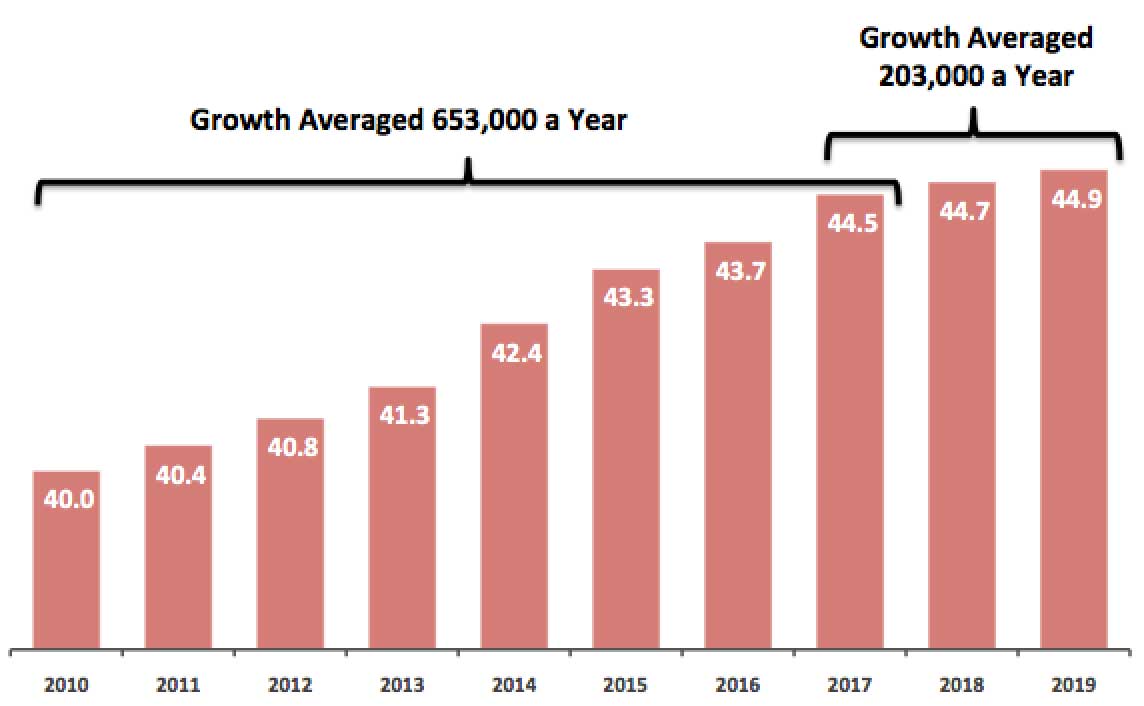

Using data from data.census.gov, a new CIS Backgrounder examines growth in the nation's immigrant population. That data, from the American Community Survey (ACS), shows that in the first two years of the Trump administration (2017 to 2019), growth in the immigrant population (legal and illegal) averaged only about 200,000 a year, in contrast to 650,000 a year from 2010 to 2017. (See Figure 1.) That Backgrounder also estimated that net migration — the difference between the number of immigrants coming vs. leaving — averaged 953,000 from 2010 to 2017, but 525,000 from 2017 to 2019. The Census Bureau has now released the public-use file of the ACS, allowing researchers to do more detailed analysis, including estimating in- and out-migration separately. Our analysis of the public-use data indicates that the falloff in net migration was caused by a substantial increase in out-migration in the first part of the Trump administration, as well as a more modest reduction in new arrivals. (All figures are through July 2019 and pre-date the impact of Covid-19.)

Figure 1. The immigrant population (legal and Illegal) has grown much more slowly since 2017, reflecting a likely "Trump Effect". |

|

|

Source: American Community Survey 2010 to 2019 from data.census.gov. |

The green bars in Figure 2 report the number of immigrants arriving each year based on the 2001 to 2019 ACS. As the ACS reflects the population on July 1 of each year, it is only possible to know how many people arrived during an entire calendar year once the following year's data is released. So, for example, the number of immigrants who arrived in all of 2018 is based on the 2019 ACS and the number arriving for all of 2017 is based on the 2018 ACS and so on. (The arrival numbers are all based on the year of arrival question in the survey.) The half-year arrival numbers shown in the blue bars are based on the survey for the year in which it is shown.

Figure 2. The decline in immigrant arrivals after 2016, even as immigrant unemployment continued improving, likely reflects Trump administration policies. (thousands) |

|

|

Source: 2001 to 2019 public-use files of the American Community Survey (ACS). |

Figure 2 shows that the number of immigrants arriving fell during the Great Recession and then rebounded, peaking at 1.7 million in 2016, the last year of the Obama administration. But in 2017, 1.4 million immigrants arrived and 1.3 million arrived in 2018. Figures for the first half of 2019 indicate that the number of arrivals in 2019 is likely to be similar to 2017 and 2018. Clearly, the slowdown in growth partly reflects a decline in newcomers. It should be pointed out that Figure 2 shows that the unemployment rate of immigrants continued to improve between 2017 and 2018, and yet the number coming fell. As we discussed in our Backgrounder on this data, the decline in immigration almost certainly reflects policy changes, not the economy.

While the arrival data shows a clear decline, the really big change seems to have been in out-migration. Simply put, out-migration is the number of immigrants leaving each year. It is possible to roughly calculate this number by taking new arrivals and subtracting growth and deaths. Performing this calculation indicates that between 2010 and 2017 about 467,000 immigrants left each year on average. But between 2017 and 2019, 975,000 left each year on average.1

While these numbers reflect our best preliminary estimates based on the data, there are some important caveats about them. First, there are margins of error around each of the numbers used for these calculations, whereas our calculations take the point estimates as givens. (See Table 2 for confidence intervals.) Sampling variability can result in significant year-to-year fluctuations. However, calculating outmigration over multiple years should provide more statistically robust estimates. Second, out-migration is calculated for the entire period 2010 to 2017, and there may have been substantial variation during those years. Third, our method for estimating half-year migration for the second half of 2010 and the second half of 2017 are somewhat crude. Even with these caveats, it appears that annual out-migration in the first part of the Trump administration (2017 to 2019) was substantially higher than the average annual rate 2010 to 2017.

While the out-migration figures seem quite high, mathematically out-migration must have increased dramatically. It is the only way to account for the numbers in Figures 1 and 2. The number of deaths does not change much year to year, so the very modest growth (Figure 1) in the face of many new immigrants arriving (Figure 2) can only be explained by high out-migration. The only other possible explanation is some kind of problem with the data. This might take the form of a coding error or perhaps immigrants, or some subpopulation of them, have become less willing to identify themselves in the ACS. But at this point there is no indication this is the case.

Figure 3 reports the number of new immigrants settling in the United States by sending region.2 Table 1 (download as an Excel file, here) reports regions with more detail, and some countries. Figure 3 and Table 1 indicate that immigration declined after 2016 from just about every region and country. The only exception seems to be Central America and to some extent South America.

Figure 3. With the exception of non-Mexico Latin America, the number of new arrivals declined from most regions after 2016. (thousands) |

|

|

Source: 2001 to 2019 public-use files of the American Community Survey (ACS). |

The biggest takeaway from these numbers, and our larger Backgrounder, is that immigration has slowed even as the economy expanded. We discuss at length in our Backgrounder, some of the policy changes under the Trump administration that seem to have had an impact on immigration levels — both in- and out-migration. The new data demonstrates that the notion that immigration operates outside the control of governmental policy is clearly wrong. Even relatively modest policy changes seem to have made a significant difference.

Table 2. Immigrant Arrivals 2000-2019

|

|||||

| Year | Number Arriving by Year |

Confidence Interval (90%) |

Number Arriving in the First Six Months of Year |

Confidence Interval (90%) |

|

| 2000 | 1,662 | 71 | 911 | 45 | |

| 2001 | 1,465 | 67 | 809 | 50 | |

| 2002 | 1,249 | 62 | 670 | 46 | |

| 2003 | 1,196 | 61 | 645 | 45 | |

| 2004 | 1,345 | 41 | 700 | 47 | |

| 2005 | 1,366 | 41 | 767 | 31 | |

| 2006 | 1,335 | 41 | 752 | 31 | |

| 2007 | 1,231 | 39 | 736 | 31 | |

| 2008 | 1,136 | 34 | 696 | 30 | |

| 2009 | 1,137 | 34 | 604 | 25 | |

| 2010 | 1,159 | 35 | 697 | 27 | |

| 2011 | 1,084 | 32 | 673 | 27 | |

| 2012 | 1,213 | 34 | 681 | 25 | |

| 2013 | 1,278 | 35 | 683 | 25 | |

| 2014 | 1,494 | 37 | 849 | 28 | |

| 2015 | 1,617 | 39 | 914 | 29 | |

| 2016 | 1,747 | 40 | 1,031 | 31 | |

| 2017 | 1,447 | 37 | 930 | 30 | |

| 2018 | 1,342 | 35 | 884 | 29 | |

| 2019 | n/a | n/a | 933 | 30 | |

|

Source: Source: 2001 to 2019 public-use files of the American Community Confidence intervals were calculated using parameter estimates using |

|||||

End Notes

1 To estimate out-migration, we use the following formula: new arrivals – (growth + deaths) = out-migration. To estimate new arrivals, we can use the year of arrival information from Figure 2 and Table 1. However, arrival data in the ACS is by calendar year and so does not match growth in the total immigrant population year over year in the ACS. The total population is for July 1 of each year. To make the arrival numbers match the growth figures for 2010 to 2017, we take half of the arrivals from 2010 (to reflect the number coming in the second half of that year) and add it to the number who come 2011 through 2016. We add to this the number who came in the first half of 2017, shown in the blue bar for that year in Figure 2. This sums to 9.942 million arrivals mid-2010 to mid-2017. We perform the same calculation for 2017 to 2019, taking half of the arrivals from 2017, and using the figures for the first half of 2019. Total arrivals mid-2017 to mid-2019 equals 2.999 million. Based on the race, age, and gender of the immigrant population we estimate 2.102 million deaths among the immigrant population 2010 to 2017 and 643,000 2017 to 2019. Finally, growth 2010 to 2017 was 4.57 million and growth 2017 to 2019 was 407,000. Plugging in the numbers for the 2010 to 2017 period, we get: 9.942 million – (4.570 million + 2.102 million) = 3.27 million or average out-migration of 467,000 a year. For the period 2017 to 2019, we get: 3 million – (.407 million + .643 million) = 1.949 million or average out-migration of 975,000 a year.

2 Regions are defined in the following manner: East Asia: China (including Hong Kong and Taiwan), Japan, Korea, Cambodia, Indonesia, Laos, Malaysia, Mongolia, Myanmar, Philippines, Singapore, Thailand, Vietnam, Other South Central Asia, Other Asia not specified; South Asia: Bangladesh, Bhutan, India, Nepal, Pakistan, Sri Lanka; Caribbean: Antigua and Barbuda, Bermuda, Bahamas, Barbados, Cuba, Dominica, Dominican Republic, Grenada, Haiti, Jamaica, St. Kitts-Nevis, St. Lucia, St. Vincent and the Grenadines, Trinidad and Tobago, West Indies, Caribbean not Specified, Americas not Specified; Central America: Belize, Costa Rica, El Salvador, Guatemala, Honduras, Nicaragua, Panama, Other Central America; South America: Argentina, Bolivia, Brazil, Chile, Colombia, Ecuador, Guyana, Peru, Paraguay, Uruguay, Venezuela, Other South America; Middle East: Afghanistan, Iran, Kazakhstan, Uzbekistan, Iraq, Israel, Jordan, Kuwait, Lebanon, Saudi Arabia, Syria, Yemen, Turkey, Azerbaijan, Kyrgyzstan, United Arab Emirates, Algeria, Egypt, Morocco, Libya, Sudan; Europe: United Kingdom, Ireland, Denmark, Norway, Sweden, Other Northern Europe, Austria, Belgium, France, Germany, Netherlands, Switzerland, Other Western Europe, Greece, Italy, Portugal, Spain, Albania, Belarus, Bulgaria, Croatia, Czech Republic, Slovakia, Hungary, Latvia, Lithuania, Macedonia, Moldova, Poland, Romania, Russia, Ukraine, Bosnia and Herzegovina, Serbia, Armenia, Other Southern Europe, Other Eastern Europe, Europe not specified; Sub-Saharan Africa: Cameroon, Cabo Verde, Congo, Ethiopia, Eritrea, Gambia, Ghana, Guinea, Ivory Coast, Kenya, Liberia, Nigeria, Rwanda, Senegal, Sierra Leone, Somalia, South Africa, Tanzania, Togo, Tunisia, Uganda, Democratic Republic of Congo (Zaire), Zambia, Zimbabwe, South Sudan, Western Africa not Specified, Other Africa not Specified, Eastern Africa not Specified; Oceania/Elsewhere: Australia, Fiji, Marshall Islands, Micronesia, New Zealand, Tonga, Samoa, Other U.S. Island Areas, Oceania not Specified, or at Sea, American Samoa. Latin America Other than Mexico includes the regions of Caribbean, Central America and South America.