This report is based on newly released data from the 2022 Survey of Income and Program Participation (SIPP). Analysis of this data shows both immigrants and the U.S.-born make extensive use of means-tested anti-poverty programs, with immigrant households significantly more likely to receive benefits. This is primarily because the American welfare system is designed in large part to help low-income families with children, which describes a large share of immigrants. The ability of immigrants, including illegal immigrants, to receive welfare benefits on behalf of U.S.-born citizen children is a key reason why restrictions on welfare use for new legal immigrants, and illegal immigrants, are relatively ineffective.

Among the findings:

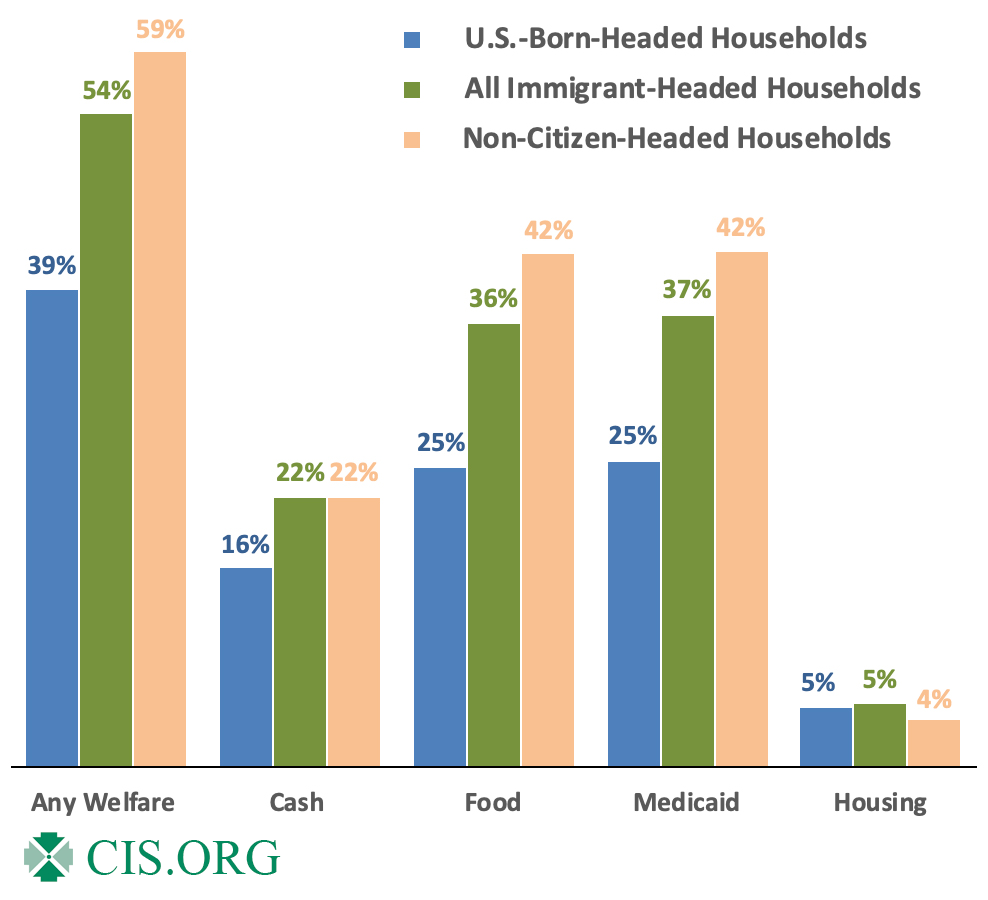

- The 2022 SIPP indicates that 54 percent of households headed by immigrants — naturalized citizens, legal residents, and illegal immigrants — used one or more major welfare program. This compares to 39 percent for U.S.-born households.

- The rate is 59 percent for non-citizen households (e.g. green card holders and illegal immigrants).

- Compared to households headed by the U.S.-born, immigrant-headed households have especially high use of food programs (36 percent vs. 25 percent for the U.S.-born), Medicaid (37 percent vs. 25 percent for the U.S.-born), and the Earned Income Tax Credit (16 percent vs. 12 percent for the U.S.-born).

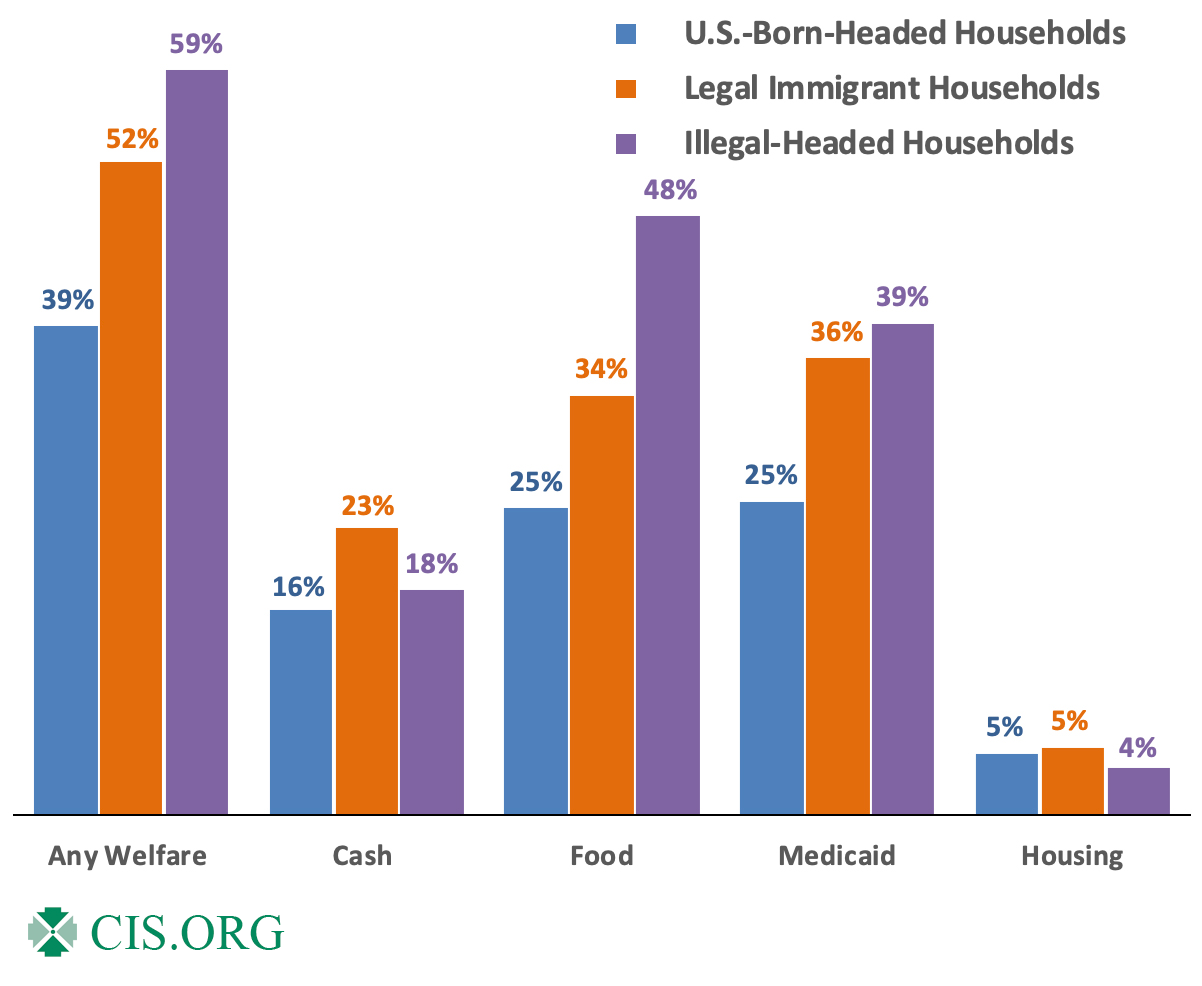

- Our best estimate is that 59 percent of households headed by illegal immigrants, also called the undocumented, use at least one major program. We have no evidence this is due to fraud. Among legal immigrants we estimate the rate is 52 percent.

- Illegal immigrants can receive welfare on behalf of U.S.-born children, and illegal immigrant children can receive school lunch/breakfast and WIC directly. A number of states provide Medicaid to some illegal adults and children, and a few provide SNAP. Several million illegal immigrants also have work authorization (e.g. DACA, TPS, and some asylum applicants) allowing receipt of the EITC.

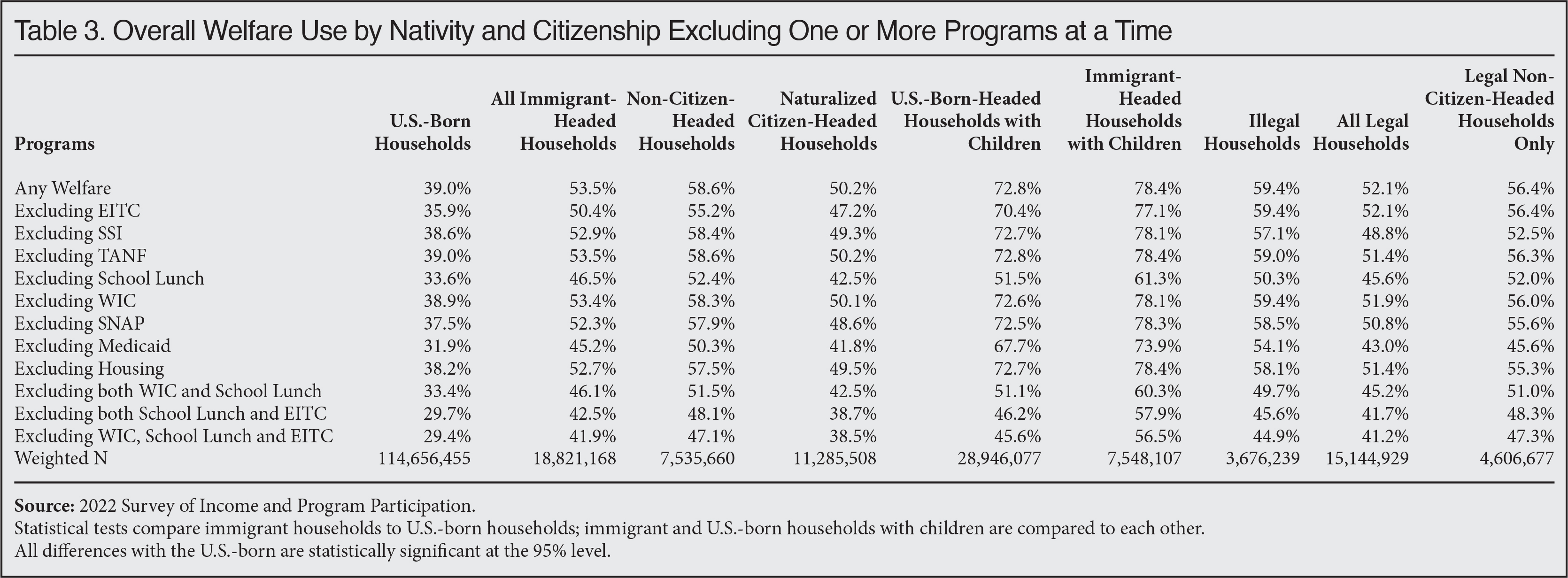

- No one program explains the higher overall use of welfare by immigrants. For example, excluding the extensively used but less budgetary costly school lunch/breakfast program, along with the WIC nutrition program, still shows 46 percent of all immigrant households and 33 percent of U.S.-born households use at least one of the remaining programs.

- The presence of extended family or unrelated individuals does not explain immigrants’ higher welfare use, as the vast majority of immigrant households are nuclear families. Further, of immigrant households comprised of only a nuclear family, 49 percent use the welfare system compared to 35 percent of nuclear family U.S.-born households.

- The high welfare use of immigrant households is not explained by an unwillingness to work. In fact, 83 percent of all immigrant households and 94 percent of illegal-headed households have at least one worker, compared to 73 percent of U.S.-born households.

- Immigrants’ higher welfare use relative to the U.S.-born is partly, but only partly, explained by the larger share with modest education levels, their resulting lower incomes, and the greater percentage of immigrant households with children.

- Immigrant households without children, as well as those with high incomes and those headed by immigrants with at least a bachelor’s degree, tend to be more likely to use welfare than their U.S.-born counterparts.

- Most new legal immigrants are barred from most programs, as are illegal immigrants, but this has a modest impact primarily because: 1) Immigrants can receive benefits on behalf of U.S.-born children; 2) the bar does not apply to all programs, nor does it apply to non-citizen children in some cases; 3) most legal immigrants have lived here long enough to qualify for welfare; 4) some states provide welfare to otherwise ineligible immigrants on their own; 5) by naturalizing, immigrants gain full welfare eligibility.

Introduction

Terminology and Data. We use the terms “immigrant” and “foreign-born” synonymously. The foreign-born includes all individuals who were not U.S. citizens at birth — naturalized citizens, green card holders, illegal immigrants, and those with long-term temporary visas such as guestworkers. In contrast, the U.S.-born, also called natives or native-born, are all those who were born U.S. citizens. We also use the terms “immigrant household” and “U.S.-born household” based on the nativity of the head of the household, which the government generally refers to as the “house holder”. Our primary data source is the 2022 Survey of Income of Program Participation (SIPP), which measures welfare use in 2021, and is the most recent data available.1 The survey is collected by the Census Bureau, which describes the SIPP as “the premier source of information” on “program participation”. The bureau is clear that illegal immigrants are included in its surveys, though as we discuss in the appendix of this report, there is likely a significant undercount of illegal immigrants in the SIPP.2 We use this data to examine use of the major welfare programs for immigrant and U.S.-born households.

Defining Welfare. The definition of welfare can be debated. However, the Census Bureau states that benefits from “social welfare programs” are generally “based on a low income means-tested eligibility criteria”. Such programs are by definition specifically designed to uplift those with low incomes. The bureau specifically gives Supplemental Security Income (SSI), Temporary Assistance for Needy Families (TANF), Supplemental Nutrition Assistance Program (SNAP), and the Women, Infants, and Children (WIC) nutrition program as examples of “social welfare”. Some have tried to argue that Medicare and Social Security should be considered welfare programs. However, the Census Bureau considers these programs as distinct from welfare, referring to them as “social insurance programs” because they are not means-tested, and instead “are usually based on eligibility criteria such as age, employment status, or being a veteran”. In addition, recipients of social insurance typically must have paid into programs like Social Security and Medicare before receiving benefits.

We follow the Census Bureau definition of welfare and limit our analysis to means-tested anti-poverty programs. The major programs examined in this report are the Earned Income Tax Credit (EITC), Supplemental Security Income (SSI), Temporary Aid to Needy Families (TANF), free and reduced-price school lunch and breakfast (school meals), the Women, Infants, and Children (WIC) nutrition program, Supplemental Nutrition Assistance Program (SNAP, also called food stamps), Medicaid, and subsidized and public housing.3

Why Welfare Use Matters. The more than $900 billion spent collectively each year on the above programs represents a substantial share of the federal budget and even of state budgets in the case of Medicaid.4 Looking at welfare use provides insight into whether immigrants or the U.S.-born are a net fiscal burden. This is not simply due to the direct costs they create, but also because those accessing means-tested programs typically pay little to no federal or state income tax, which is by far the largest source of federal revenue.5 Further, use of welfare is also an indication that immigration may be adding to the low-income population struggling to support itself. By their consumption of scarce public resources, immigrants may also make it more difficult to assist the poor already here. Finally, use of welfare is a key measure of self-sufficiency and therefore is an important measure of how immigrants are adapting to life in America.

How to Think About Welfare. What constitutes “high” or “low” use is an open question. It is common to discuss immigrant welfare use relative to the U.S.-born. At least traditionally, one of the most important arguments for immigration is that it benefits the United States — that is, the existing population of Americans. From this perspective, it is certainly reasonable to argue that with the exception of the roughly 6 percent of the total immigrant population who were admitted for humanitarian reasons (e.g. refugees and asylees), immigrant welfare use should be very low.6 To be sure, the extent to which immigrants use welfare does not settle the immigration debate. There are many other things to consider when deciding on immigration policy. That said, immigrants’ use of welfare should not be seen as them “gaming” the system nor should it be understood as reflecting a moral failing on their part. There is no evidence in this data that immigrants are using fraudulent means to access these programs. Rather, they are simply using programs for which they or their children are eligible at a time when the social stigma surrounding these programs has largely disappeared.

Findings

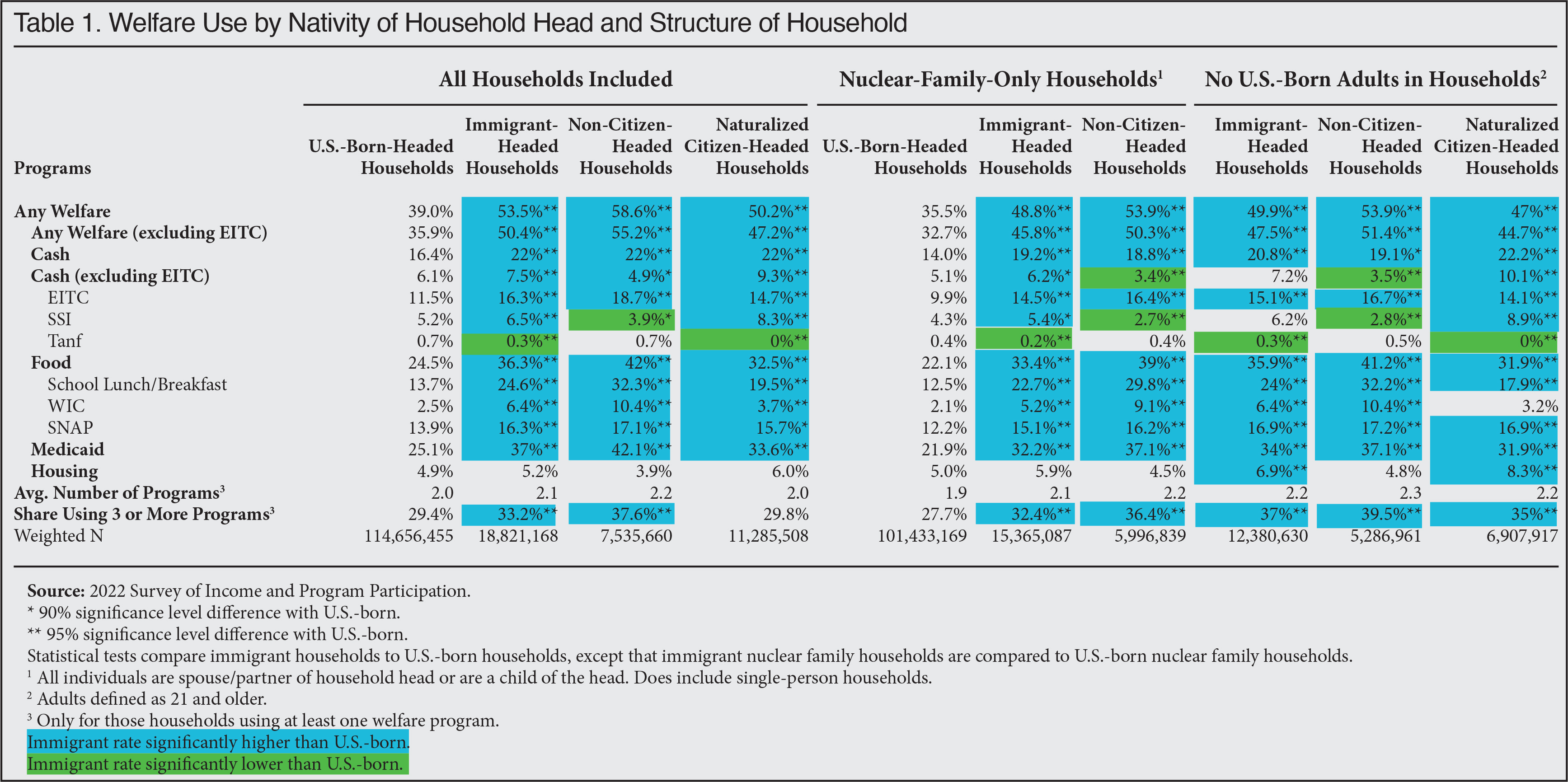

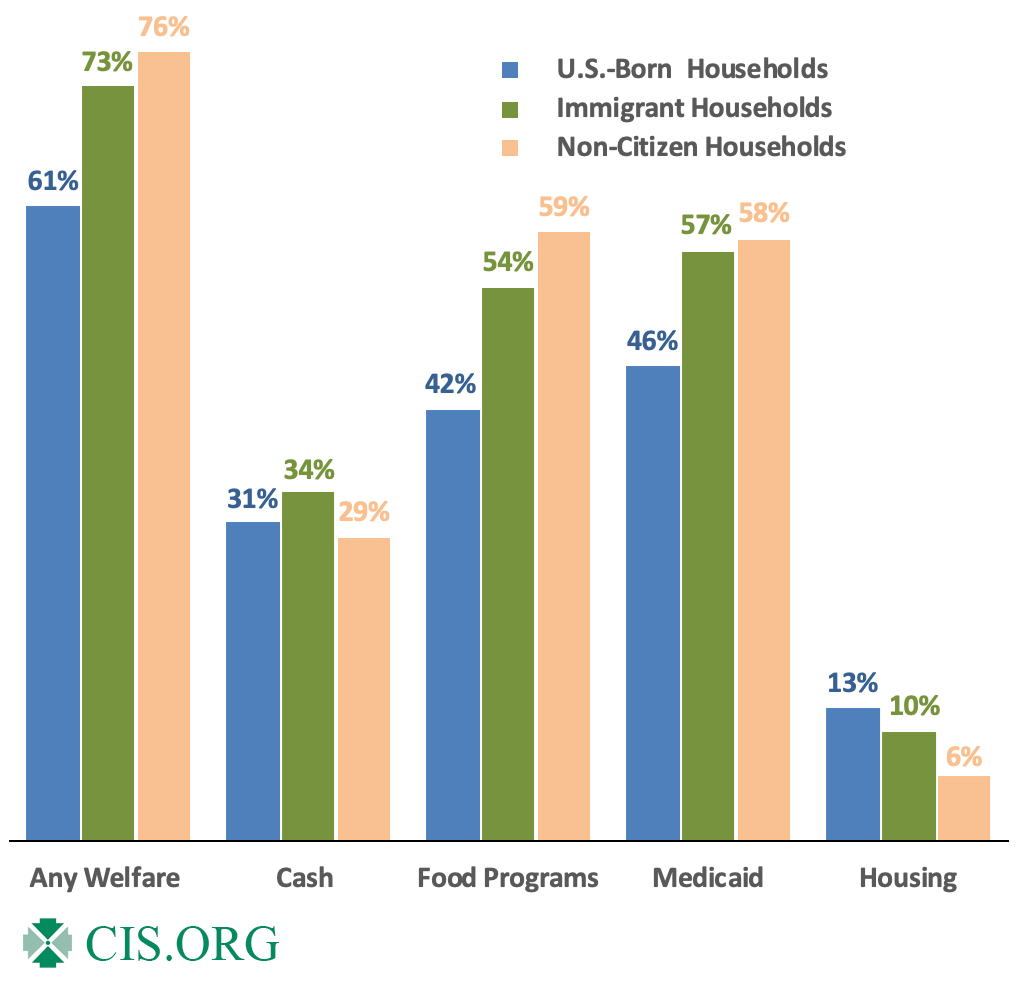

Overall Use of Programs. Figure 1 and Table 1 report our estimates of welfare use from the SIPP based on the nativity of the household head. The figure shows that welfare use is common for both immigrant and native households. Based on the 2022 SIPP, 53.5 percent of all immigrant-headed households and 39 percent of households headed by the U.S.-born used at least one major program. The 14.5 percentage-points higher rate for all immigrants relative to the U.S.-born is statistically significant. If we excluded naturalized American citizens, and look only at households headed by a non-citizen, it shows a welfare use rate of 58.6 percent — nearly 20 percentage points higher than the U.S.-born. This is also a statistically significant difference.

Figure 1. Welfare Use by Nativity |

|

|

Source: 2022 Survey of Income and Program Participation. See text for welfare programs included in each category. |

|

The overall rates include the Earned Income Tax Credit (EITC). In our view, this program is unambiguously a welfare program, as it is a means-tested anti-poverty program.7 However, it is different from the other programs because recipients must have earned income to receive it.8 That is, they have to work. For this reason, we report overall welfare use with and without the EITC in Table 1.9 Whether the EITC is included or not, the difference in overall welfare use between the foreign born and the U.S.-born is still 14.5 percentage points, which is statistically significant.

Specific Programs. Looking at broad categories of welfare programs in Figure 1 shows that immigrant-headed households compared to U.S.-born households have especially high use of Medicaid (37 percent vs. 25 percent for natives) and food programs (36 percent vs. 25 percent for natives). The difference for cash programs when the EITC is included — 22 percent vs. 16 percent — is also statistically significant. Table 1 provides more specific information for individual programs and significance tests for each. The table shows that compared to households headed by the U.S.-born, immigrant households have statistically significant higher use for every program except TANF and housing. It should be noted that the SIPP is not very good at measuring use of the seldom-used TANF. This is particularly the case for sub-populations such as immigrants or non-citizens because such a small share of all U.S. residents — immigrant or U.S.-born — avail themselves of what is now a relatively small program.10

Household vs. Families. A household according the Census Bureau is all the people living in the same housing unit. Households can have more than one family. A family is defined by the Census Bureau as any two or more related individuals (by blood, marriage, or adoption) living in the same household. Much of the prior research on welfare use has used households as the unit for a number of reasons.11 Nonetheless, there is a stereotype of immigrant households as very large, containing multiple generations, more than one family, distant relatives, or unrelated individuals. It might be supposed such households, with so many disparate people, are more likely to have someone on welfare. Of course, more people also means more potential workers, raising the income and reducing the need to access welfare. In fact, at 83 percent, immigrant households are more likely to have at least one worker present than U.S.-born households at 73 percent. Moreover, immigrant households with at least one worker have 1.34 workers on average compared to 1.09 workers in U.S.-born households with at least one worker.

Despite the stereotype of very large households, on average immigrant households have 2.9 people in the SIPP. While certainly larger than the 2.3 individuals in the average U.S.-born household, most immigrant households are not very large. In fact, only 7 percent of immigrant households have more than five people. Furthermore, the overwhelming majority (82 percent) of immigrants can be described as “nuclear households” — comprised of either a one-person household or a household with a head, his or her spouse/partner, and the head’s children.12 Some 88 percent of U.S.-born households fit this definition as well. In short, in more than four out of five immigrant households there are no individuals unrelated to the head, nor are there any in-laws, grandchildren, or any other non-nuclear relatives.

Welfare Use by Household Type. The middle of Table 1 reports welfare for only what we henceforth will call “nuclear family households". At 48.8 percent, the overall welfare use rate for immigrant households of this kind is not very different from the 53.5 percent for all immigrant households. At 35.5 percent, the welfare use rate for nuclear family U.S.-born households is similar to all such households. The gap in overall welfare use between immigrants and the U.S.-born narrows a bit to 13.3 percentage points when only nuclear households are compared, down from 14.5 percentage points when all households are considered. But the higher rate for immigrants remains statistically significant. The same is generally true for most individual programs. For nuclear households headed by a non-citizens, the gap with the U.S.-born overall also narrows only slightly. In general, the structure of immigrant households is not that different from households headed by the U.S.-born, at least as measured by the SIPP. Further, to the extent immigrant households include extended family members and unrelated individuals, it does not explain their higher use of welfare.

The Presence of U.S.-Born Adults. The right side of Table 1 looks at immigrant households excluding U.S.-born adults. These are typically the spouse, partner, or U.S.-born adult children of the household head. These individuals have full welfare eligibility, making it possible that their presence explains a good deal of the welfare use of immigrant households. While these individuals are certainly common in immigrant households, when they are not included the welfare use of immigrant households only drops to 49.9 percent overall. Again, this is not very different from the 53.5 percent for all immigrant households. This difference is still nearly 11 percentage points higher than for U.S.-born households and it is statistically significant. For individual programs, the gap between immigrant and U.S.-born households also narrows a bit in most cases when households with U.S.-born adults are excluded. For non-citizen households, the welfare use rate overall is also lower when U.S.-born adults are excluded, but it is still 53.9 percent and the difference with the U.S.-born is still statistically significant. The presence of U.S.-born adults in immigrant households is common and their presence does increase welfare use for immigrant households somewhat, but excluding them does not make that much difference.

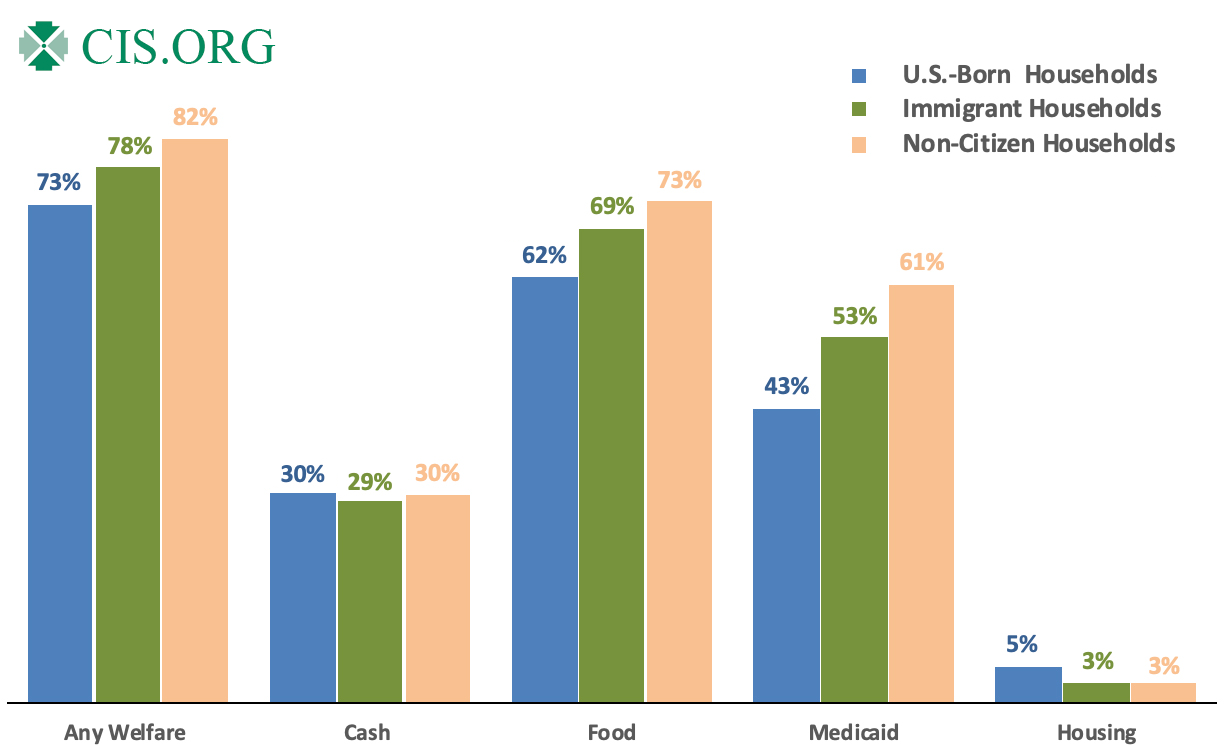

Legal Immigrants. Determining the legal status of immigrants in the Census Bureau data is always difficult and comes with significant uncertainty. The appendix at the end of this report explains how we do this. In short, we use the self-reported characteristics of immigrants to assign weighted probabilities to the foreign-born to create a representative population of illegal immigrants, which we subtract from the total immigrant population to estimate the legal immigrant population (mainly naturalized citizens and green card holders).13 Figure 2 and Table 2 (Excel link) show that legal immigrants, which includes naturalized citizens, have high welfare use overall at 52.1 percent. With the exception of housing and TANF, legal immigrants have higher use rates than the U.S.-born for most programs. Turning to households headed by non-citizen, legal immigrants (mainly green card holders), shows even higher overall welfare use at 56.4 percent. Looking at specific programs, legal, non-citizen households have statistically significant higher welfare use than the U.S.-born for the EITC, school lunch/breakfast, WIC, and Medicaid. There are no programs in which legal non-citizens have statistically significant lower use.

Figure 2. Welfare Use by Nativity and Legal Status |

|

|

Source: 2022 Survey of Income and Program Participation. See text for welfare programs included in each category. |

Illegal Immigrants. Figure 2 and Table 2 indicate that households headed by illegal immigrants, also called the undocumented or unauthorized, have higher overall welfare use rates than the U.S.-born and the difference is statistically significant. We estimate that 59.4 percent of illegal immigrant households use one or more welfare programs. Compared to the U.S.-born, illegal-headed households use every program at statistically significant higher rates than the U.S.-born, except for SSI, TANF, and housing. Even the larger share of illegal immigrant-headed households using three or more programs at 35.5 percent (shown at the bottom of Table 2) is statistically significant relative to U.S.-born households.14 Assuming our estimates are correct, the SIPP data indicates that use of the welfare system by illegal immigrant households is extremely common. It is also important to note that we have no evidence that their use rates reflect cheating or fraud. Their high rates of welfare use primarily reflect their generally lower education levels and their resulting low-incomes, coupled with the large share who have U.S.-born children who are eligible for all welfare programs from birth.

Why Is Illegal Immigrant Welfare Use So High? The high use of welfare by illegal immigrant-headed households may seem implausible. However, there are several things to consider: First, more than half of all illegal immigrant households have one or more U.S.-born children.15 Second, many states offer Medicaid directly to illegal immigrants. For example, a dozen states offer Medicaid to all low-income children regardless of immigration status and even more states provide it to all low-income pregnant women, again without regard to legal status. A few states go beyond this and offer Medicaid to other adult illegal immigrants.16 Third, illegal immigrant children have the same eligibility as citizens for free subsidized school lunch/breakfast and WIC under federal law. Fourth, six states also offer SNAP benefits to illegal immigrants under limited circumstances.17 Fifth, several million illegal immigrants have work authorization, which provides a Social Security number and with it EITC eligibility. This includes those with DACA, TPS, many applicants for asylum, and those granted suspension of deportation and withholding of removal.18 Sixth, prior research indicates that the overwhelming majority of illegal immigrants have no education beyond high school and, as a result, a very large share of illegal immigrants have incomes low enough to qualify for welfare.19 Finally, it should be remembered that the job of the those in the welfare bureaucracy is to help low-income residents receive the welfare for which they are eligible.

What if Illegal Immigrants Don’t Use Welfare? Some may remain convinced that illegal immigrants are unaware of welfare or are too fearful to use it. But if we are mistaken and somehow illegal immigrants do not use welfare as we show, then mathematically it must mean that the number of legal immigrant households using welfare must be correspondingly much higher because immigrant-headed households in the SIPP can only be headed by legal or illegal immigrants. If we assume that illegal aliens are in the survey, which they must be, but use no welfare, then all the households receiving welfare would have to be legal immigrant households. If that is the case, then the welfare use rate for legal immigrants would have to be 66.5 percent, compared to the 52.1 percent we actually estimate.20 Use of individual programs would increase correspondingly as well. The reality is that illegal immigrants are included in the SIPP, a large share of them are poor, and they or their U.S.-born children have welfare eligibility; and many take advantage of this eligibility.

Illegal Immigrant Welfare Use Matters. Beyond just the direct impact on public coffers of illegal immigrant use of welfare, their use of these programs shows that many illegal immigrants are struggling in the United States. Moreover, if even illegal immigrant-headed households have high welfare use, then it shows that efforts to restrict immigrants from programs once in the country is politically and practically difficult and not likely to be very effective. It also means that the current influx of illegal immigrants that has caused this population to increase dramatically in the last 2.5 years has profound implications for public coffers. This is especially true because a large share of those released into the country have been granted parole. Parolees are “qualified aliens”, which means they generally have the same welfare eligibility as new permanent legal immigrants. After five years, this becomes full welfare eligibility with the exception of SSI, which requires 10 years of work.

Excluding Programs. One might think that the higher overall rate of welfare use by immigrants is caused by just one or two particular programs. But as we have already seen when we look at individual programs in Tables 1 and 2, immigrant rates are higher than those of the U.S.-born for most individual programs. Table 3 looks at this question by excluding one program at a time. The table indicates that doing so does not make much difference in the overall welfare use rates of immigrants relative to the U.S.-born. This is the case whether we look at all immigrant households, non-citizen households, legal immigrant households, or illegal immigrant households. There is one notable exception — excluding the free and subsidized school lunch/breakfast program for households with children. Doing this causes the share of immigrant households with children accessing any welfare to drop substantially, from 78.4 percent to 61.3 percent. But on the other hand, overall welfare use for U.S.-born households with children drops even more, from 72.8 to 51.5 percent. As a result, the gap between immigrant and U.S.-born households with children actually widens substantially from 5.5 percentage points when school meals are included, to 9.8 percentage points when meals are excluded. That said, all the higher use rates for immigrants reported in Table 3 are statistically significant. Clearly, no one program explains the higher overall welfare use rate of immigrants.

|

Poverty and Welfare Use. Though there are numerous exceptions, welfare is linked to income, with many programs phasing out around 250 percent of the poverty threshold. Because poverty controls for family size, it is a good way to think about the relationship of income and welfare use. In 2021, based on the SIPP, 14.8 percent of immigrant households were in poverty compared to 11.6 percent of U.S.-born households. Perhaps more important, 42 percent of immigrant households vs. 34 percent of U.S.-born households have incomes below 250 percent of poverty ($54,900 for a typical family of three in 2021).21 The higher rates of poverty or near-poverty for foreign-born households helps explain their higher overall use of welfare. Figure 3 shows that, as expected, both low-income immigrant and U.S.-born households make extensive use of welfare. Looking at the top portion of Table 4 (Excel link), we see that all low-income immigrant and low-income non-citizen households have statistically significant higher overall welfare use than the low-income U.S.-born. For immigrant households, the same is true specifically for the EITC, WIC, the school lunch/breakfast program, and Medicaid. The same basic pattern holds for non-citizen households. In the case of TANF and housing, all immigrant households have statistically significant lower rates than the U.S.-born and for non-citizens the rate is significantly lower for only housing.

Figure 3. Welfare Use by Nativity of Household Head with Income <250% of Poverty |

|

|

Source: 2022 Survey of Income and Program Participation. |

The lower portion of Table 4 reports use rates for nuclear households only. In general, low income households with no extended family or unrelated individuals show the same pattern as nuclear low-income U.S.-born households. The finding that low income immigrant households have higher welfare use overall and for some programs contradicts the argument made by some that low-income immigrants use welfare less than the low-income U.S.-born. Of course, focusing on low income immigrants and natives overlooks the more important issue mentioned at the outset of this discussion — the larger share of immigrant households with low incomes in the first place, which contributes to their higher welfare use.

High Income Households. One striking finding in Table 4 is that households with income above 400 percent of poverty ($87,840 for a family of three in 2021) use welfare at surprisingly high rates — 30.7 percent for immigrants and 22.6 percent for the U.S.-born. One thing to keep in mind is that we are calculating poverty based on the income and family size of the household head. If other families or individual(s) are present, then they could have incomes low enough to qualify for welfare. But their income and expense would generally have to be considered separately for them to qualify for social welfare programs. Moreover, the lower portion of Table 4 shows that 24.7 percent of nuclear family immigrant households with high incomes access one or more welfare programs, as do 20 percent of high-income nuclear U.S.-born households. This means that much of the welfare use of high-income families is not explained by the presence of extended family or unrelated individuals living with the primary high-income family. The relatively high use of welfare even of high-income nuclear family households may seem strange, however there are actually a number of ways this can happen.22

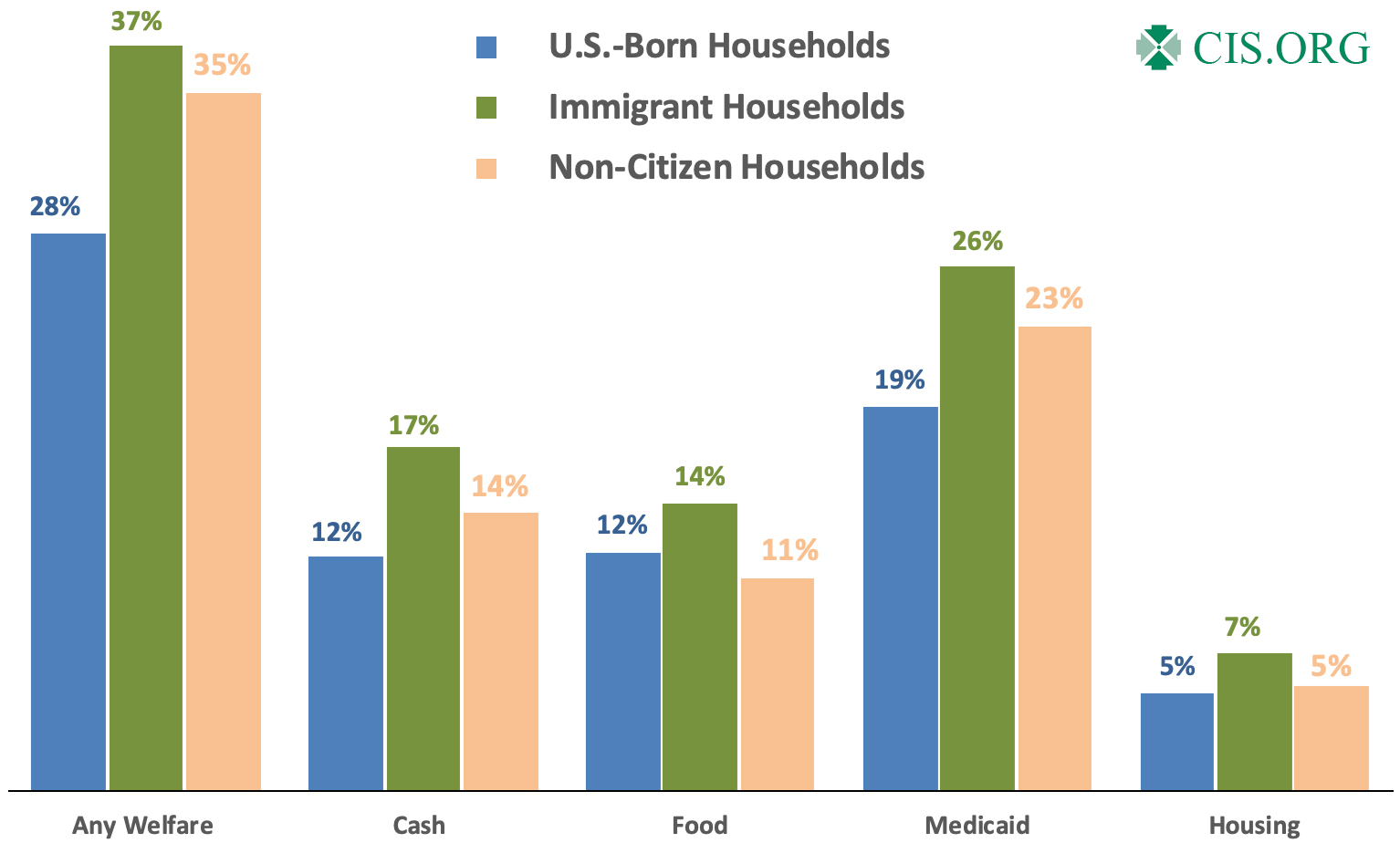

Households with Children. Much of the nation's welfare system is specifically designed to help low income parents with children. Programs like TANF (formerly called Aid to Families with Dependent Children), the Women, Infants, and Children nutrition program, free/subsidized lunch/breakfast for students, and Medicaid for children (referred to as the Children's Health Insurance Program) were explicitly created for minors. Immigrant households are more likely to have children — 40.1 percent vs. 25.2 percent of the U.S.-born. This fact contributes to immigrants’ higher use of welfare. Immigrant households are not only more likely to have children, but when they do, they are also more likely to be low-income. In the 2022 SIPP, 45.2 percent of all immigrant households with children and 55.9 percent of non-citizen households had incomes below 250 percent of poverty, compared to 35.9 percent of U.S.-born-headed households.

Figure 4. Welfare Use by Households with Children |

|

|

Source: 2022 Survey of Income and Program Participation. |

Table 5 (Excel link) shows that 78.4 percent of immigrant households with children use at least one welfare program, and it is 72.8 percent for U.S.-born households with children, which is a statistically significant difference. While the overall rate of welfare use seems extraordinarily high for immigrants and natives, it should be remembered that Table 3 showed that for households with children, excluding the school/lunch breakfast program reduces the use rate to 61.3 percent for immigrant households with children and to 51.5 percent for U.S.-born households with children. That said, the difference is actually larger when school meals are excluded. Table 5 shows that immigrant households with children have significantly higher use of WIC, school meals, and Medicaid, while immigrant use is significantly lower for TANF and housing. It seems fair to say based on this data that a very large share of immigrants come to America, have children, struggle to provide for them, and so turn to taxpayers for support. This can be seen as especially problematic given that there is already a large number of Americans who are also struggling to provide for their children.

Households with Children by Legal Status. As already discussed, the presence of U.S.-born children is one of the main ways illegal immigrants can access welfare. Of minor children in legal and illegal immigrant households, we estimate that nearly nine out of 10 are U.S.-born. Furthermore, even illegal immigrant children are eligible for some programs nationally, and some states add to this eligibility. Equally important, of households with children headed by illegal immigrants, 60.4 percent have incomes below 250 percent of poverty. This is the case for 39.4 percent of households headed by legal immigrants with children. The large share with low incomes means their welfare use rates will be high as well.

Table 6 (Excel link) reports use of welfare for households with children based on the legal status of the household head. At 84.6 percent, the share of illegal immigrant households with children accessing one or more welfare programs is very high, as is the 76 percent for legal immigrants. Both are significantly higher than the 72.8 percent for U.S.-born households, though the rate for the U.S.-born is certainly very high as well. Table 6 also shows that illegal immigrant households with children use school meals, WIC, and Medicaid at significantly higher rates than the U.S.-born, while their use of the EITC and SSI is lower. As for legal immigrant households, their use of WIC, and Medicaid is significantly higher than their U.S.-born counterparts, while their use of SNAP and housing is significantly lower.

Households Without Children. Figure 5 reports welfare use for households without children. Table 7 (Excel link) provides more detailed information. Since a primary goal of the welfare system is to help low-income households with children, it is not surprising that use of welfare by childless households is much lower than for households with children. Yet, as Table 7 shows, at 36.9 percent the share of immigrant households using welfare or even the 27.6 percent for U.S.-born childless households can be seen as surprisingly high. The 9.3 percentage-point higher use of any welfare program by immigrant households without children is statistically significant. Childless immigrant households have significantly higher use rates than the U.S.-born for all the programs that childless households can access — the EITC, SSI, SNAP, Medicaid, and housing.23 We also find that welfare use for childless non-citizens and legal immigrant-headed households tends to be higher than for U.S.-born households. But this is not true for illegal immigrants without children. This is to be expected since so much of illegal immigrant welfare use is due to the presence of their U.S.-born children.

Figure 5. Welfare Use for Households Without Children |

|

|

Source: 2022 Survey of Income and Program Participation. |

In interpreting the findings in Figure 5 and Table 7 it should be kept in mind that most immigrant and U.S.-born households do not have children. This means that childless households have a very large impact on the welfare use rates for all immigrant and all U.S.-born households. As already discussed, one of the reasons immigrant households have higher use of welfare overall is that they are more likely to have children, and such households are more likely to access welfare. However, another factor contributing to immigrants’ higher welfare use is that immigrant households without any children are also significantly more likely to use welfare than childless U.S.-born households.

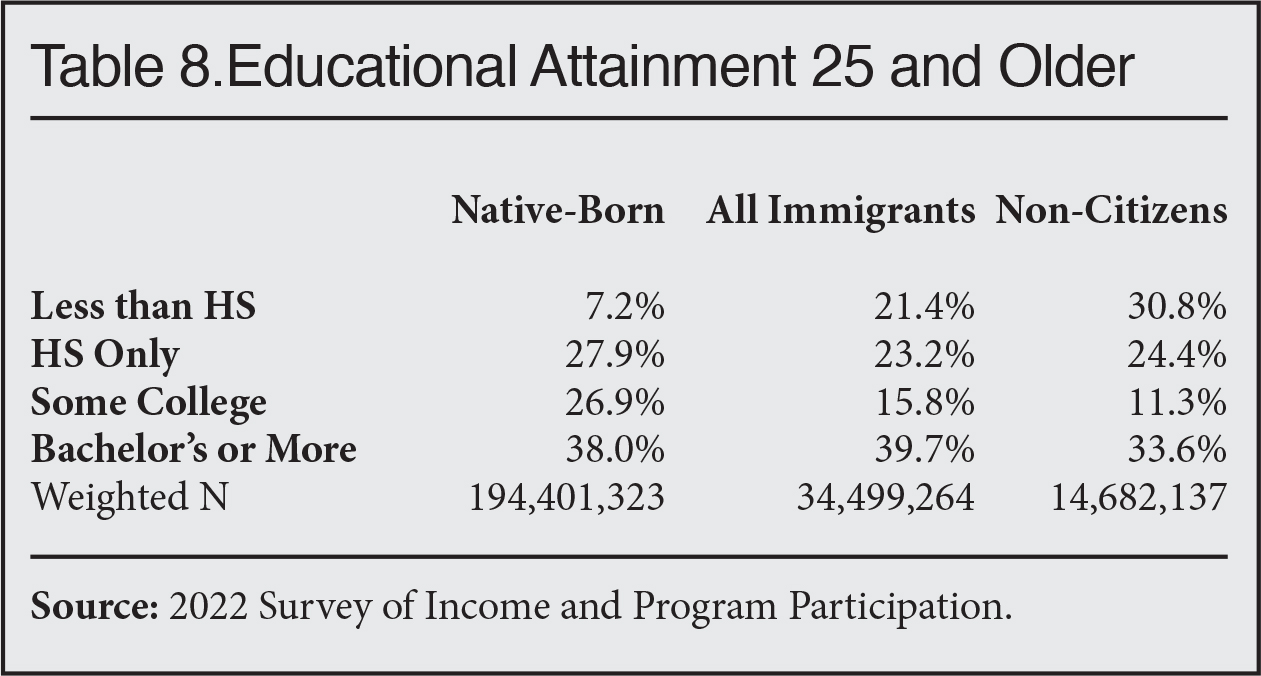

Immigrant Education Levels. It is well established that educational attainment is one of the best predictors of income in the modern American economy and, as a result, welfare use. Table 8 reports the educational attainment of immigrants 25 and older based on the SIPP. It shows 44.6 percent of immigrants have no education beyond high school, compared to 35.1 percent of the U.S.-born. At the higher end of the educational distribution, the share of immigrants and the U.S.-born with at least a bachelor’s degree is quite similar at 39.7 percent for immigrants and 38 percent for the U.S.-born.24 Further, analysis of standardized tests shows that immigrants with the same nominal education level as a U.S.-born person score significantly lower on literacy, math, and computer skills and tend to earn less as a result.25 This is the case even for immigrants with a bachelor’s degree earned overseas. As we have seen, a significantly larger share of immigrant households are in poverty or have low income more broadly defined. Given the larger share of immigrants with modest levels of education and their lower average skills when they are foreign educated, it is not surprising that a larger share of households headed by immigrants have incomes low enough to qualify for welfare.

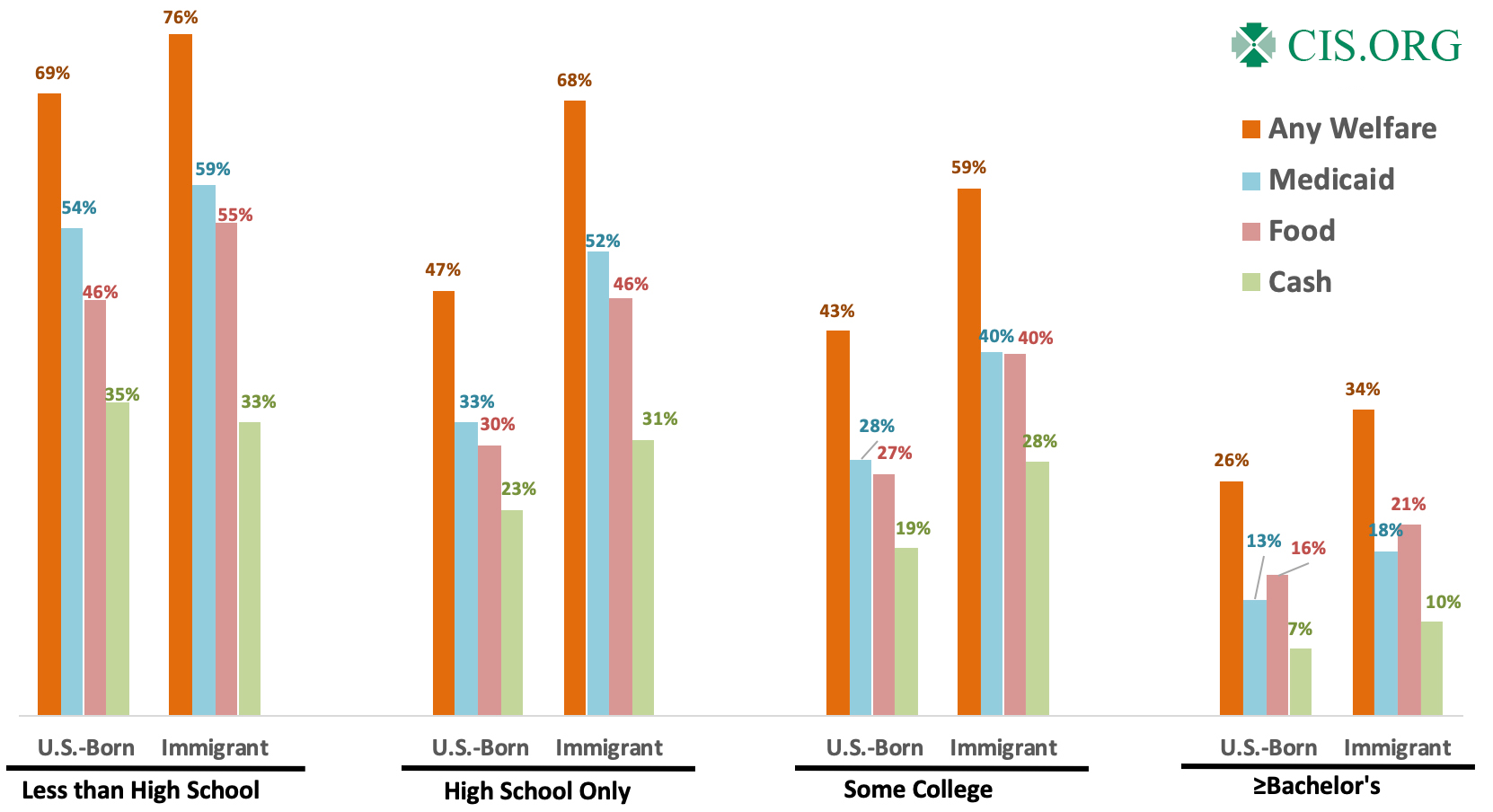

|

Welfare Use by Education Level. Figure 6 shows welfare use by types of programs based on the education level of the household head. Table 9 (Excel link) provides more detailed information on program use and significance tests. As expected, educational attainment has a huge impact on welfare use for immigrants and the U.S.-born. For example, 75.7 percent of immigrant households headed by someone without a high school diploma access one or more welfare programs. For U.S.-born households with a head with this level of education it is 69.1 percent. In contrast, 34 percent of immigrant households headed by someone with at least a bachelor’s use welfare as do 26.1 percent of U.S.-born households headed by someone with at least a bachelor’s. Educational attainment is a very good predictor of income and, not surprisingly, welfare use. The fact that a much larger share of immigrant households are headed by someone with a modest level of education is one of the reasons immigrant households generally have high welfare use.

Figure 6. Welfare Use by Education and Nativity of the Household Head |

|

|

Source: 2022 Survey of Income and Program Participation. |

The second important finding in Figure 6 is that the overall share of immigrant households using welfare is higher at every level of education than for the U.S.-born with the same education. However, this is not true for all individual programs. Looking at Table 9 (Excel link) we see that households headed by less-educated immigrants — less than high school and high school only — use of welfare is higher than the U.S.-born for some programs, but lower for others, while there is no statistically significant difference for others. What is perhaps more striking, well-educated immigrant households tend to have higher welfare use overall and for most programs than their U.S.-born counterparts. This parallels our finding that higher-income immigrant households have higher welfare use than higher-income U.S.-born households. This pattern exists for all immigrants and naturalized citizens, but is not really the case for non-citizen households.

Welfare Use for Working Households. Table 10 (Excel link) looks at welfare use for households with one or more workers. The idea that work precludes welfare use is simply wrong. In fact, it is not too much to say that one of the primary goals of the American welfare system is to assist low-wage workers, particularly those with children. Table 10 shows that 53.2 percent of immigrant households with at least one worker access the welfare system, as do 39.8 percent of working U.S.-born households. In the 2022 SIPP, most households accessing the welfare system had a worker present. This is the case for 73 percent of all U.S.-born households using one or more welfare programs, and 83 percent of all immigrant households using welfare. That said, immigrant households with a worker are more likely to use welfare than working U.S.-born households for most individual programs. This is true even though, as already mentioned, immigrant households with at least one worker have 1.34 workers on average compared to 1.09 workers in U.S.-born households with at least one worker.26 The larger share of immigrant workers with lower levels of education likely helps to explain this result.

Why Welfare Use by Working Households Matters. The fact that welfare use is so high for working households is a reminder that immigrants are not simply workers. In the 2022 SIPP, 83 percent of all immigrant households had at least one worker, compared to 73 percent of U.S.-born households. So immigrant households are significantly more likely to be “working households”. But this fact has not prevented immigrant households from having higher welfare use rates than the U.S.-born overall. Arguing, as former President George W. Bush once did, that all that really matters is matching employers with “willing workers” is an extremely simplistic way of thinking about immigration. Immigrants are people with families and children. They have their own cultures, values, and perspectives. Their presence in the United States has impacts for many aspects of American society, including the welfare system.

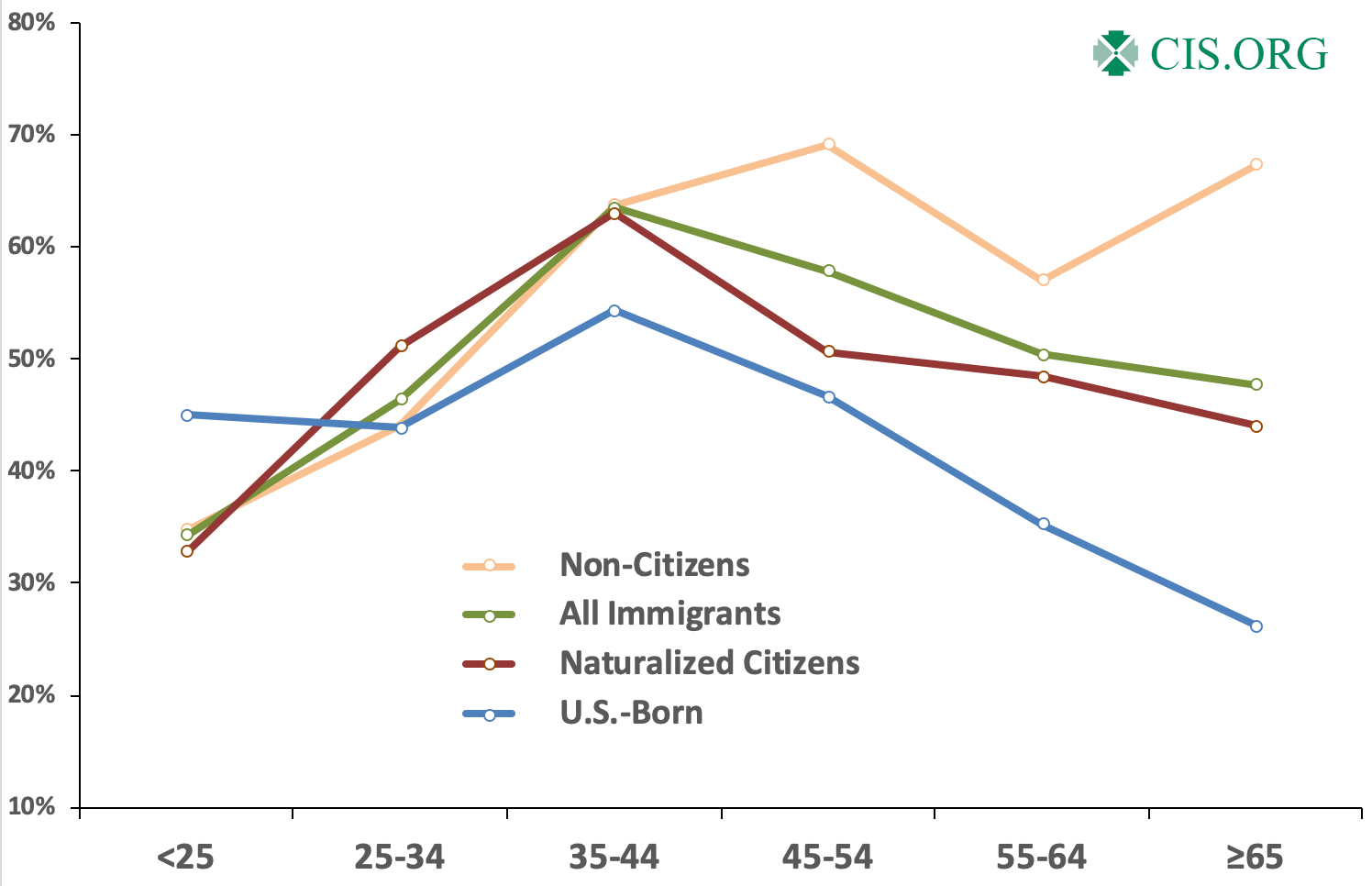

Welfare Use by Age. Figure 7 reports the share of immigrant and U.S.-born households using one or more welfare programs based on the age of the household head. It shows that the youngest households, those with heads under age 25, have the lowest overall use of welfare, with the U.S.-born having higher use rates than the foreign-born in this youngest age group. However, very few households fall into the age category, with only 4.2 percent of U.S.-born households and just 2.8 percent of immigrant households having a head under 25. This is because most immigrants arrive after age 24 and relatively few young people (immigrant or native) have set up their own households. Figure 7 shows that, with the exception of non-citizens, welfare use tends to peak when the household head is 35 to 44 and then decline to some extent thereafter. Because use of welfare falls off more steeply for the U.S.-born as they age, immigrant-headed households have higher welfare use in all the older age cohorts than the U.S.-born of the same age. Moreover, the largest gap between immigrants and the U.S.-born in overall use of welfare tends to be among households headed by those 65 and older.

Figure 7. Welfare Use Based on Age, Nativity, and Citizenship of the Household Head |

|

|

Source: 2022 Survey of Income and Program Participation. |

Table 11 (Excel link) reports detailed program use and significance tests by nativity, citizenship, and age of the household head. It shows that, for a few programs, immigrant households tend to use less than the U.S.-born at younger ages. In contrast, in the households headed by people in the older age cohort, immigrant use tends to be significantly higher for most programs. In fact, when all immigrants are considered in the four age groups 35 and older only TANF and SSI are used significantly less by immigrants in some cases. Young immigrants tend to be newer arrivals for the simple reason that immigrants age over time. It seems older and more established immigrants make the most extensive use of welfare relative to older U.S.-born Americans. This is not surprising since as immigrants age they generally are allowed to access more welfare programs and they are more likely to have children. If those children are U.S.-born, which is true in the vast majority of cases, then they will have full welfare eligibility.

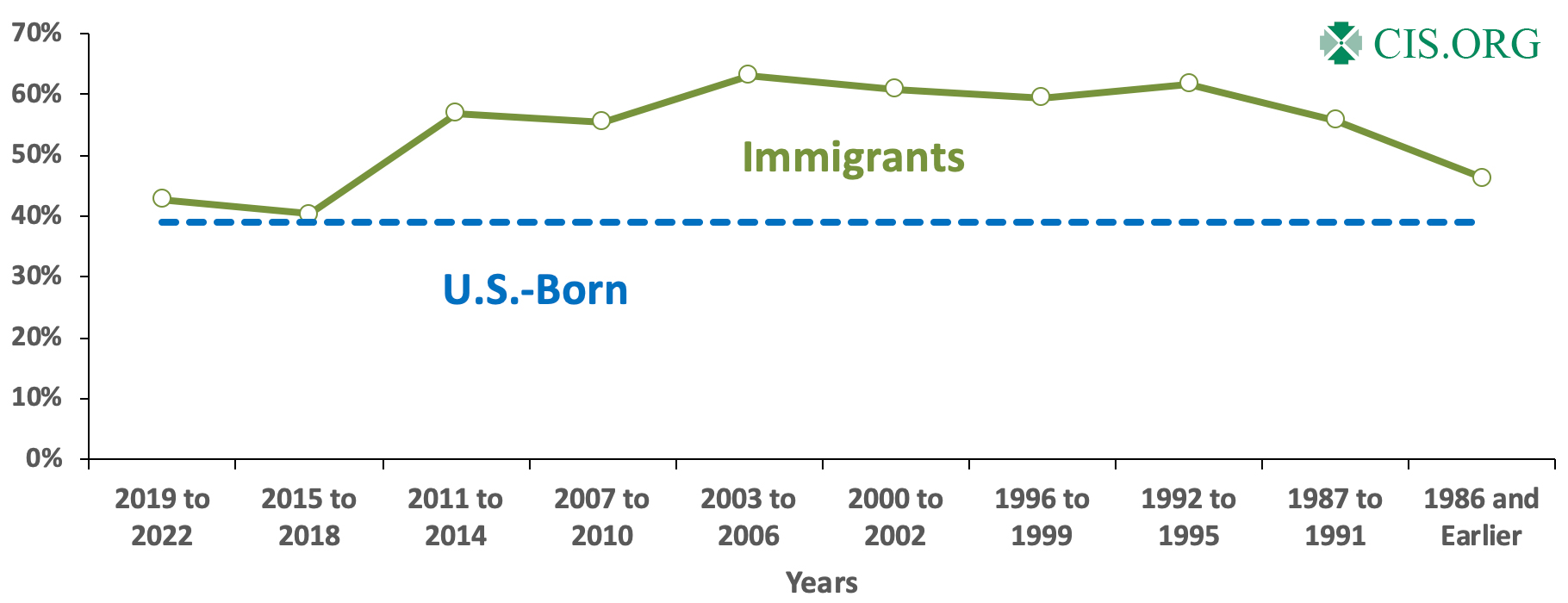

Welfare Use Based on Year of Arrival. The SIPP asks respondents the year they came to the United States to live. We can use responses to this question to explore how immigrant welfare use changes the longer they are in the country. Figure 8 shows that in general welfare use is surprisingly high for households headed by new arrivals. It then rises and stays higher than the U.S. born for decades. Based on the 2022 data, it seems clear that welfare is not simply something only newcomers use, but then once they adapt to life here their use declines rapidly.

Figure 8. Use of Any Major Welfare Program for Immigrant Households Based on Year of Arrival |

|

|

Source: 2022 Survey of Income and Program Participation. |

Given the sample size of the immigrant population in the SIPP, it is not possible to divide the population by year of entry and individual programs.27 However, we are able to report in Table 12 (Excel link) types of welfare programs and significance tests by year of arrival. In general, after the first few years in the country, immigrant households tend to have higher welfare use than U.S.-born households for most types of programs.

Table 13 (Excel link) reports detailed welfare use and significance tests for immigrant households based on if the head has lived in the country for less than 10 years or 10 or more years. The first thing to note is that the vast majority of immigrant households are headed by someone who has been in the country for 10 or more years — 15.6 million immigrant households, or 83 percent. This means that most immigrant households are unlikely to be impacted by the 10-year deeming requirement, which considers their sponsor's income, if they have one, when determining eligibility for some programs. The same goes for the five-year bar on some welfare programs that applies to most new non-humanitarian green card holders. Table 13 also shows that immigrant households headed by someone in the U.S. for 10 or more years have a higher welfare use rate than the U.S.-born overall and for almost all programs. Households headed by a non-citizen in the country for less than 10 years have lower welfare use for some programs than the U.S.-born. But only about 14 percent of all immigrant households are headed by non-citizens who have been in the country for less than 10 years. These newly arrived non-citizens do not impact the overall numbers that much.

Sending Region and Race. The public-use SIPP does not release detailed information on the country of birth for immigrants. It only provides the immigrants’ home “region”, which is defined very broadly. Table 14 (Excel link) reports welfare use by the regions available in the SIPP. The table shows that households headed by immigrants from the Western Hemisphere and Africa tend to have the highest rates of welfare use; and, those from Asia and Europe the lowest. Asian and European immigrants tend to be more educated so it is not surprising they have lower welfare use. Table 15 (Excel link) reports welfare use by race. It is important to note that the racial groups shown for the U.S.-born in Table 16 are generally not the offspring of today’s immigrants, who very often are still children. Rather, in the vast majority of cases the parents and ancestors of the U.S.-born are the progeny of people who arrived decades or in many cases centuries earlier.

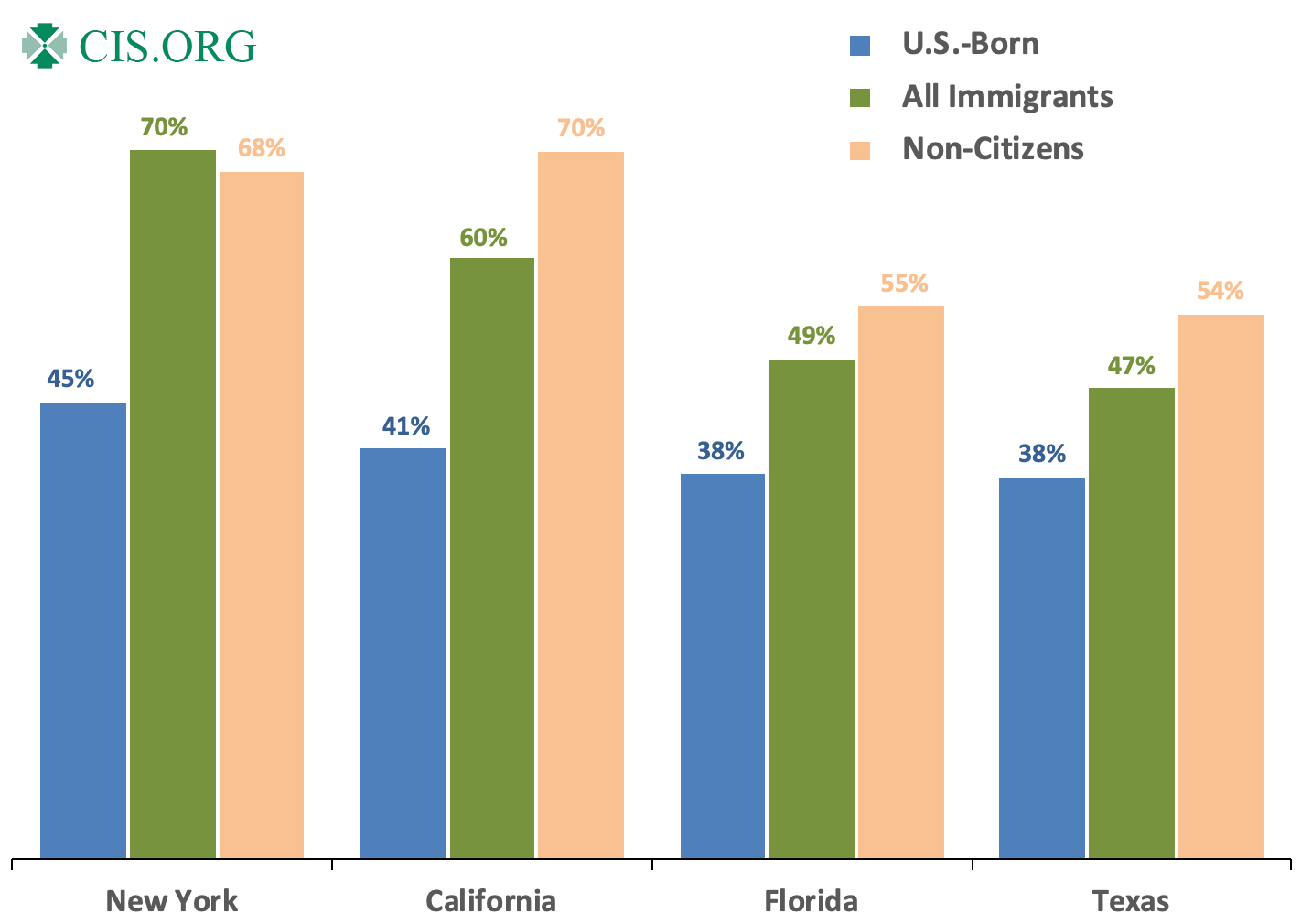

Welfare Use in New York and California. The sample size of immigrants in the SIPP makes it difficult to find statistically significant differences at the state level. Figure 9 and Tables 16 through 19 show welfare use by nativity in the four largest states. New York and California not only have the fourth and first largest immigrant populations respectively, they both have relatively generous welfare systems, particularly toward immigrants. Table 16 (Excel link) shows that, at 70.3 percent, New York’s immigrant households have the highest immigrant welfare use in the four largest states. This is 25.1 percentage points higher than the 45.2 percent of U.S.-born households in the state using welfare. The non-citizen rate in the Empire State is 22.8 percentage points higher than that of the U.S.-born; both differences are statistically significant. Table 17 (Excel link) shows that in California 59.5 percent of immigrant households use one or more welfare programs in the Golden State, which is quite high. The rate for non-citizens is 70 percent, which is even higher. The gap between all immigrants in the state and the U.S.-born is 18.8 percentage points and is even larger at 29.2 percentage points for non-citizens compared to the U.S.-born, which are both statistically significant. It seems likely that the very high welfare use by immigrants in these two states, both in absolute terms and relative to the U.S.-born, in part reflects the relatively generous welfare systems in both states, particularly for immigrants.28

Figure 9. Share of Households Using Any Welfare by State and Nativity of Household Head |

|

|

Source: 2022 Survey of Income and Program Participation. |

Welfare Use in Texas and Florida. In contrast to New York and California, the states of Florida and Texas, which have the second and third largest immigrant populations respectively, have less generous welfare systems. The 49.4 percent of immigrant households in Florida using welfare and the 46.6 percent in Texas are much lower than in New York or California, as are the rates for non-citizens. Still, as shown in Table 18 (Excel link) immigrant households’ welfare use overall in the Sunshine State is 11.3 percentage points higher than for the U.S.-born and its 16.6 percentage points higher for non-citizens; both of these differences are statistically significant. The 8.9 percentage points higher welfare use for immigrants relative to the U.S.-born (Table 19, Excel link) in the Lone Star State is also statistically significant, as is the 16.1 percentage points higher welfare use for non-citizens. The less generous welfare policies of Florida and Texas do seem to matter, though more research would be necessary to determine if the relatively lower welfare use in those state reflects state policies or characteristics of the immigrants. For individual programs, welfare use tends to be higher for immigrants in all four states. But the differences are not always statistically significant, which is not surprising given the sample size at the state level and the much smaller share of the population that uses individual programs compared to overall use.

Conclusion

It is sometimes asserted that immigrant welfare use is low because most new legal immigrants as well as illegal immigrants are barred from using most welfare programs. But the 2022 Survey of Income and Program Participation (SIPP), which is specifically designed to measure use of government programs, shows that more than half of immigrant households use one or more major welfare programs, compared to 39 percent of households headed by the U.S.-born. We also estimate that about 59 percent of households headed by illegal immigrants access welfare, as do 52 percent of households headed by legal immigrants.

Immigrant households can access welfare in a number of different ways. First, immigrants are able to receive benefits on behalf of U.S.-born children; the restrictions on new arrivals do not apply to all programs, nor do the restrictions apply to non-citizen children for some types of benefits. Furthermore, most legal immigrants have lived here long enough to qualify for welfare. A number of states also provide welfare to otherwise ineligible immigrants on their own. Finally, by naturalizing, immigrants gain full welfare eligibility.

High immigrant use of welfare is due in part to the larger share with modest levels of education and resulting low incomes. Another factor contributing to higher immigrant use of welfare is that they are more likely to have children than U.S.-born households. The vast majority of these children are U.S.-born with full welfare eligibility. Many immigrants come to America and work, have children, and then struggle to support them and turn to taxpayers and the welfare system for assistance. Somewhat surprisingly, we also find that immigrant higher-income, better-educated, and childless households are all more likely to use welfare than their U.S.-born counterparts. It is not entirely clear why this is the case. There is research showing that foreign-educated immigrants tend to be significantly less skilled as measured by standardized tests and typically earn less than immigrants educated in the United States or natives with the same education level. This could help explain why households headed by better educated immigrants have higher welfare use than households headed by natives with the same education level. But it would not explain why childless or higher-income immigrant households use more welfare than their U.S.-born counterparts.

One factor that does not explain immigrant households’ higher use of welfare is an unwillingness to work. In fact, immigrant households are more likely to have a worker present than households headed by the U.S.-born. But all eight major programs (SSI, TANF, EITC, school meals, WIC, SNAP, Medicaid, and housing) examined in the report can be received by workers or members of their households if incomes are low enough.

It is also the case that the presence of extended family or unrelated individuals does not explain immigrant households’ heavy use of welfare. When we look at only households comprised of nuclear families, which constitute the overwhelming majority of immigrant and U.S.-born households, the gap between the two groups remains about the same.

The high use of welfare by immigrants is important for a number of reasons. First, it shows that past efforts to prevent immigrants, including illegal immigrants, from using the welfare system have not been very effective. Second, immigrant welfare dependence means that current immigration is unlikely to improve the fiscal picture of the government. This is not simply because of the direct costs of the programs; it is also because those receiving welfare typically pay little to no federal income tax. All of this means that the current family-based legal immigration system, and widespread toleration of illegal immigration, is very unlikely to shore up public coffers, even though immigrants have relatively high rates of work.

If we wish to avoid high use of welfare by the foreign-born in the future, then moving to a system that selects immigrants based on their education or skills would likely be the most effective way of doing so. Since about one-fifth of all immigrant households using welfare are headed by an illegal immigrant, enforcing immigration laws, and reducing the size of the illegal immigrant population would also be helpful in lowering future immigrant welfare use.

There is an unfortunate tendency for many to think of immigrants one-dimensionally. This is especially true in the business community, where they are seen simply as workers. But this ignores the enormous impact immigrants have on American society, including the welfare system. Given their welfare use rates, knowledge of government programs is clearly extensive in immigrant communities. To be sure, use of welfare is only one facet of immigration. But the impact immigrants are having on the welfare system and public coffers at least needs to be part of the immigration debate.

Appendix: Estimating Illegal Immigrants in the SIPP

Based on our estimates of illegal immigrants in the monthly CPS, we believe the total weighted illegal immigrant population in mid-2022 in the monthly CPS was 11.8 million. We use this number to estimate illegal immigrants in the 2022 SIPP. The SIPP and CPS use similar weighting schemes, but the surveys cover different population universes. Since there is no body of research on the SIPP vs. the CPS coverage of illegal immigrants, we assume that the ratio of illegals in the two surveys is the same as the ratio of non-citizen, post-1980 Hispanics, a population that significantly overlaps with illegal immigrants. The ratio is .75 when the 2022 July monthly CPS is compared to the 2022 SIPP. Our analysis therefore assumes that there is a weighted count of 8.85 million illegal immigrants in the 2022 SIPP (11.8 million times 0.75).

To determine which SIPP respondents are most likely to be illegal aliens, we first exclude immigrant respondents who are almost certainly not illegal aliens — for example, spouses of native-born citizens; veterans; adults who receive direct welfare payments; people who have government jobs; Cubans (because of special rules for that country); immigrants who arrived before 1981 (because the 1986 amnesty should have already covered them) or they arrived after age 59; people in certain occupations requiring licensing, screening, or a government background check (e.g., doctors, pharmacists, and law enforcement); people likely to be on student visas, and workers who earned more than $150,000 in the past year.

The remaining candidates are weighted to replicate known characteristics of the illegal population (age, gender, continent of origin, certain states of residence, and length of residence in the United States). CIS has previously used the Department of Homeland Security (DHS) as the source of those known characteristics; however, DHS’s most recent estimates are for 2018. We instead turn to 2019 estimates from the Center for Migration Studies (CMS). The resulting illegal population, which consists of a weighted set of SIPP respondents, is designed to match CMS on the known characteristics listed above, as well as education. The total size of the population, however, is controlled to our 8.85 million estimate of illegal immigrants in the SIPP.

End Notes

1 It is possible Covid and the economic dislocations it created caused unusually high welfare use in 2021, the year measured by the 2022 SIPP. However, the 2021 SIPP, which measured program use in 2020, when the pandemic peaked, shows that 51.4 percent of immigrant households used at least one welfare program and the figure was 36.1 percent for the U.S.-born. Unemployment, economic growth, and labor force participation were all worse in 2020 than 2021, so it does not seem that the results in the 2022 SIPP reflect unusually high welfare use caused by Covid. Further, our prior analysis of the 2018 SIPP, well before Covid, shows similar use rates for individuals programs to the 2021 and 2022 data, though overall use is higher in the more recent data.

2 The Census Bureau website states that “unauthorized migrants are implicitly included in the Census Bureau estimates of the total foreign-born population”. For the SIPP in particular, the bureau states in its Source and Accuracy statement for the survey that the sample used to weight the SIPP specifically includes unauthorized migration.

3 State-sponsored general assistance (GA) cash programs are relatively small and are also included in our analysis under cash programs, though figures are not reported separately for GA, which only a very small share of immigrant or U.S.-born households use.

4 The Congressional Research Service reported that the federal government spent more than $817 billion in 2020 on the major welfare programs examined in this report. See “Federal Spending on Benefits and Services for People with Low Income: FY2008-FY2020”, Congressional Research Service, December, 2021. In addition, state governments spend more than $200 billion annually on Medicaid alone.

5 The public-use Current Population Survey Annual Social and Economic Supplement (CPS ASEC) shows that, of immigrant households that receive at least one of these welfare programs, 66 percent paid no federal income tax in 2022. Further, the average tax payment of those using these programs is just 5 percent of those not using one of these programs. We use the CPS ASEC because it includes estimated tax payments, though it is thought to not measure welfare as well as the SIPP. The SIPP has no tax payment estimates. Also, because there are some schools where all children receive free school lunch, even if they come from higher income households, we exclude the free and reduced priced school lunch/breakfast program from the above estimate.

6 To the best of our knowledge, there are no up-to-date estimates of the total population of refugees, those formally granted asylum, and other smaller categories admitted for “humanitarian” reasons living in the United States. However, some 3.5 million refugees have been settled in the United States since 1975. Adding asylum and other categories brings that number closer to four million over the last five decades. Making reasonable assumptions about mortality and emigration, it is likely the total number of immigrants who had been admitted for humanitarian reasons was very roughly three million in 2022. Assuming a total immigrant population of 48 million in the middle of 2022 would mean about 6 percent of the total foreign-born were humanitarian immigrants. Of course, this is only a rough estimate but it seems certain that this population could not be dramatically larger or smaller than 6 percent of all immigrants. There is good evidence that humanitarian immigrants, especially recent arrivals, make extensive use of the welfare system. It is therefore certainly reasonable to argue that non-humanitarian immigrants should have very low rates of welfare use to offset costs created by refugees, asylees, and the like.

7 Unlike other programs reported in the SIPP, respondents are asked about use of the EITC, “for the tax year preceding the reference period”. In the 2022 SIPP, the reference period is 2021 (January to December); however, for the EITC, the survey is measuring use in 2020. This is done because people typically need to file their income tax return to know if they are eligible for the program. This does have the effect that households in the SIPP that have no workers during the reference period can still be reported as having received the EITC.

8 While technically there is a work requirement for TANF, numerous exceptions exist, which differ from state to state. The exceptions can include, but are not limited to, the following: the child is under one year of age; the child is under age 6 and the parent(s) are unable to obtain child care; the parent(s) are disabled; the parent(s) need to care for someone else in the household; the child’s guardian is over 60; the parent(s) need treatment for drug or alcohol use; or the child’s mother is pregnant. None of this applies to the EITC, which simply requires income from earnings without exception.

9 It is worth pointing out that, as we will discuss later in this report, most households that access welfare programs — immigrant and U.S.-born — have at least one worker. So, the idea that working and use of welfare are separate is itself incorrect.

10 HHS reports there were only 804,000 families on TANF in 2021. While families are not exactly the same as households, we also find just 809,000 households used TANF in the 2022 SIPP. This is less than 1 percent of all households. Only 59,000 of these are immigrant households in the SIPP; this constitutes just 0.3 percent of all immigrant households in the survey. It is not likely the SIPP can accurately measure use of a program used by such tiny percentage of the immigrant population.

11 The National Research Council 1997 study also included a household-level analysis in its fiscal estimates because "the household is the primary unit through which public services are consumed". The Census Bureau in more than one study, also reported use of social services by household. The Heritage Foundation used households as the unit of analysis in their analysis as well. The late Julian Simon of the Cato Institute, himself a strong immigration advocate, also argued that it did not make sense to examine individuals when looking at the fiscal impact of immigrants. He observed that, "One important reason for not focusing on individuals is that it is on the basis of family needs that public welfare, Aid to Families with Dependent Children (AFDC), and similar transfers are received." For this reason, Simon examined families, not individuals. While not exactly the same as households, as Simon also observed, the household "in most cases" is "identical with the family". Another reason to look at households is that some of the welfare variables in the SIPP are reported at the household level.

12 On average, nuclear family immigrant households have 2.6 members compared to 2.1 members in U.S.-born nuclear-family-only households. This larger size reflects in part the fact that immigrants tend to have more children on average.

13 The SIPP attempts to capture the entire U.S. population and so long-term temporary visa holders should also be among the legal immigrant population — mainly guestworkers and foreign students.

14 Tests of statistical significance are only based on the sample size and the other properties of the SIPP. It must be remembered that legal status, unlike being foreign-born or a non-citizen, is an imputed value, which means it has added uncertainty. The significance tests do not account for the added uncertainty of our imputed value.

15 This eligibility extends even to housing. HUD’s handbook covering regulations states that if at least one member of a family is eligible (e.g., a U.S.-born child), then the family can live in federally subsidized housing, though they may receive prorated assistance. New York City has a similar rule for its own housing programs.

16 A good recent example of this is California’s expansion of Medicaid access to low-income illegal immigrants 50 and older. The state also covers all income-eligible young adults as well. In New York State, illegal immigrant adults with DACA can also be enrolled in Medicaid.

17 According to the National Immigration Law Center, six states provide SNAP benefits to illegal immigrants even if they do not have U.S.-born children, typically only if they meet certain hardship requirements in addition to having low incomes.

18 Based on administrative data, we estimated in 2021 that there were roughly two million illegal immigrants with work authorization and valid Social Security numbers (SSNs), which allows receipt of the EITC. Since 2021, the administration has further expanded work authorizations to illegal immigrants with the recent influx of asylum applicants. Prior research by the Social Security Administration also estimated some 700,000 illegal immigrants use stolen SSNs. It is simply unclear if such individuals would be detected and prevented from receiving the EITC by the IRS. It should be noted that our methodology for selecting illegal immigrants assumes that only those with citizen children may receive the EITC. Any immigrant receiving the EITC without having a U.S.-born child is assumed to be a legal immigrant.

19 The Center for Migration Studies estimates that in 2019 67 percent of illegal immigrants had no education beyond high school, 14.5 percent have some college, and 18.5 percent have a bachelor’s or more. The Migration Policy Institute’s estimate based on pooled data from 2015 to 2019 shows that 70 percent of illegal immigrants have no education beyond high school, 12 percent have some college, and 18 percent have at least a college education.

20 We can do this calculation rather simply by assuming that the roughly 2.18 million illegal-headed households using welfare are all actually legal-headed households so that there are a total of about 10.07 million legal households using welfare out of the total of 15.14 million legal immigrants we estimate are in the 2022 SIPP. Individual programs would be correspondingly higher, too.

21 In 2021, the poverty “line” or “threshold” for the typical family of two was $17,420, $21,960 for a family of three, and $36,500 for a family of four. It should be noted that there are differences depending on the presence of children, if the household head is 65 and older, or if the family resides in Alaska or Hawaii.

22 One of the more common ways a person could be on welfare in the higher-income households, even a nuclear-family-only household, is if the household head has an unmarried partner or adult child whose income and expenses were reported separately when they applied for benefits. This could allow them to receive Medicaid, SSI, EITC, and even WIC if they are pregnant. This should not happen for programs such as SNAP or housing because eligibility for these programs is generally based on household income, not family or individual income. Among the less common ways a higher-income household can have a person or persons on welfare include the following: In the SIPP person(s) can join a household during the year. If that person used welfare prior to joining the household, it would still count as welfare use by someone in the household during that year. Further, poverty status in the SIPP reflects annual income. If a household’s income was much lower for part of the year, then it is possible that individuals in a household could have qualified for welfare at that time, even though the household’s total income by the end of the year was much higher. Moreover, while the free and subsidized school lunch and breakfast program is normally linked to income, there are some schools where all students receive free meals and this probably explains much of the use of this particular program for high-income households. Additionally, foster children can sometimes retain their welfare eligibility for Medicaid, and other programs without regard to their parents’ income, though households with foster children are not included in our nuclear family households as these children are unrelated the head. In addition, premature babies can be enrolled for Medicaid in many states, often as secondary insurance, without their parents meeting strict income requirements. Finally, it is possible the SIPP is picking up some fraudulent use of welfare, but we have no evidence for this. It is more likely there are some coding errors in the data.

23 Table 7 does show some use of TANF, WIC, or school meals by childless households, which should not be possible. Assuming there are no coding errors in the data, this rare circumstance arises in the SIPP if a child lived in the household at some point during the year and received these programs but was not living there at the beginning of the year, which is when we measure if there is a child present. Also, a pregnant woman on WIC, who has no other children, would constitute a household without children using the WIC program. But use of TANF, WIC, and school meals combined total less than 1 percent in the table and has no meaningful impact on the overall results.

24 Calculating educational attainment by legal status is not really possible given that we use education as a predictor of legal status. See the appendix for a discussion of our methods for determining the legal status of SIPP respondents.

25 Among immigrants with only a high school education the research shows that, 51 percent are foreign educated and for those with a bachelor’s it is 47 percent.

26 It should be pointed out that overall and for a few programs working households actually have higher welfare use than households without a worker. While this may seem strange, one reason for this is that non-working households tend to be comprised of retirees and as such have access to Social Security, retirement accounts, and pensions, which can give them income that is too high to qualify for welfare. Moreover, such households typically have no children, which also makes a large difference in welfare use. The EITC is also a program that requires earned income.

27 The SIPP asks individuals the year they came to America, but then recodes the responses in two-year cohorts, primarily to preserve anonymity. So, for example, the most recent cohort in the 2022 data is those who came in 2021 and 2022, then 2019 and 2020, and so on, back to the mid-1980s when they are grouped into larger arriving cohorts by the Census Bureau. However, the number of immigrant households that fall into these small two-year groups is not very large. For this reason, in Figure 8 and Table 12 we group them into larger multi-year arrival cohorts to obtain more statistically robust results.

28 If we look at the education level of immigrants at the state level using the SIPP it shows California has the largest gap between immigrants and the U.S.-born. Of persons 25 and older, 50.2 percent of immigrants in the Golden State have no education beyond high school, compared to 28.3 percent of the U.S.-born — a 22 percentage-point difference. But in the other three states the gap is between 11 percent and 13 percent, so California is somewhat of an outlier in this regard. New York immigrants, with their very high immigrant welfare use, are not dramatically less educated than immigrants in other states. Nor are they particularly less educated relative to natives. Differences in education levels, and other measures of social capital across states, likely do explain some of the differences in welfare use. However, the way welfare is administrated in each state, specifically immigrant eligibility, almost certainly accounts for a good deal of the variation in program use by immigrants, both in absolute terms and relative to the U.S.-born.