Summary

- The Biden administration has granted parole to over one million aliens in just over two years, including over 800,000 inadmissible aliens the administration invited into the U.S. or apprehended at the border and released – and it’s just getting started.

- These Biden parolees will become “qualified aliens” with respect to eligibility for major federal welfare programs after one year in parole status. While in some cases they will become eligible to receive benefits as soon as they become “qualified”, in most cases, they will become eligible after five years as parolees. This privileged status is equivalent to that of lawful permanent residents for purposes of welfare eligibility.

- Because of severe backlogs in our immigration courts and because the Biden administration has released hundreds of thousands of aliens apprehended at the border without even bothering to issue them notices to appear in court, many of Biden’s parolees will still be in parole status after five years (and, for many, far beyond that). Once the five-year “parole payday” arrives, the cost to American taxpayers will reach about $3 billion per year per million parolees.

- Congress should seriously consider amending federal law to deny Biden’s parolees privileged access to federal welfare programs, leaving them eligible only for those welfare benefits available to illegal aliens.

Introduction

Milton Friedman famously postulated that “It’s just obvious that you can’t have free immigration and a welfare state.” President Biden is aiming to prove Friedman wrong.

In the Personal Responsibility and Work Opportunity Reconciliation Act of 1996 (PRWORA), Congress dramatically curtailed the federal means-tested benefits (read: welfare) available to noncitizens and set forth a “national policy with respect to welfare and immigration”, stating in part that “the availability of public benefits [should] not constitute an incentive for immigration to the United States” and “[i]t is a compelling government interest to remove the incentive for illegal immigration provided by the availability of public benefits.”

PRWORA, however, contains a gaping vulnerability that will in a few short years result in a multi-billion-dollar bill to American taxpayers. The vulnerability? PRWORA grants parolees in such status for at least a year eligibility for major federal welfare programs on the same basis as it does lawful permanent residents. This is not really a big issue in those rare instances in which the Department of Homeland Security grants parole in circumstances contemplated by Congress. But it becomes a huge issue in the context of the Biden administration’s abuse of the parole program. Team Biden has already — in little more than two years — paroled in excess of one million aliens, including those whom DHS released on parole after they were apprehended along the border and those that DHS invited into the U.S. as parolees despite their not being admissible under the duly-enacted laws of the United States. After five years of presence in the U.S., Biden’s parolees will become eligible (per PRWORA) for billions of dollars a year in federal welfare benefits. And they are likely to spend many years, if not decades, in the U.S., and give birth to many U.S. citizen children. As Sen. Everett Dirksen is reputed to have said, “A billion here, a billion there, and pretty soon you're talking real money.”

The Biden Administration’s Misadministration of Parole

The statutory parole power provides that:

[The Secretary of Homeland Security] may ... in his discretion parole into the United States temporarily under such conditions as he may prescribe only on a case-by-case basis for urgent humanitarian reasons or significant public benefit any alien applying for admission to the United States, but such parole of such alien shall not be regarded as an admission of the alien and when the purposes of such parole shall, in the opinion of the [Secretary], have been served the alien shall forthwith return or be returned to the custody from which he was paroled and thereafter his case shall continue to be dealt with in the same manner as that of any other applicant for admission to the United States.

Congress was clear in granting this power to the executive branch in 1952 that:

[The power should be] carefully restricted to those cases where extenuating circumstances clearly require such action and that the discretionary authority should be surrounded with strict limitations. ... to permit the Attorney General to parole inadmissible aliens into the United States in emergency cases, such as the case of an alien who requires immediate medical attention before there has been an opportunity for an immigration officer to inspect him, and in cases where it is strictly in the public interest to have an inadmissible alien present in the United States, such as, for instance, a witness or for purposes of prosecution. [Emphasis added.]

As I have written, while the executive branch’s abuse of the parole power has been a perennial problem almost since its inception, President Biden has taken that abuse to a new level:

-

The Biden administration has notoriously used the parole power to release into our communities hundreds of thousands of illegal aliens apprehended at the border.

-

Could it get any worse? [In January,] the Biden administration issued press releases announcing new “border enforcement measures to improve border security” and “create additional safe and orderly processes” for Cubans, Haitians, Nicaraguans, and Venezuelans “fleeing humanitarian crises”. As DHS proclaims:

[T]hese processes will provide a lawful and streamlined way for qualifying nationals of Cuba, Haiti, Nicaragua, and Venezuela ... to seek advance authorization to travel to the United States and be considered, on a case-by-case basis, for a temporary grant of parole. ... These processes will allow up to 30,000 qualifying nationals per month from all four of these countries to reside legally in the United States for up to two years and to receive permission to work here, during that period.

This represents the arrival of up to 360,000 aliens a year. And the administration could up the number with the stroke of a pen. It sure sounds like a categorical parole program intended to flout the immigration laws passed by Congress, the sort of program regarding which Congress thought it had bid good riddance.

-

Until [the announcement], the Biden administration was pursing this agenda under the guise of relative secrecy for Mexicans and Central Americans, as my colleague Todd Bensman has uncovered. Now, post-election, the breathtaking scale of what President Biden is attempting is all out in the open.

According to my calculations, at the very least, the Biden administration has granted parole to 1,075,664 aliens. Even excluding the almost 200,000 Afghans and Ukrainians granted parole, the number of Biden parolees is at the very least 880,220. Here are the numbers, month-by-month:

- January 21-31 2021: 261

- February 2021: 889

- March 2021: 1,607

- April 2021: 2,994

- May 2021: 5,731

- June 2021: 8,156

- July 2021: 10,706

- August 2021: 24,072

- September 2021: 25,841

- October 2021: 16,880

- November 2021: 15,353

- December 2021: 23,098

- January 2022: 18,576

- February 2022: 13,413

- March 2022: 36,777

- April 2022: 91,250

- May 2022: 68,527

- June 2022: 54,894

- July 2022: 39,877

- August 2022: 31,090

- September 2022: 95,191

- October 2022: 68,822

- November 2022: 90,468 + 5,587 (estimated Venezuelan parolees, November-December 2022, pursuant to the new migration enforcement process for Venezuelans)

- December 2022: 130,505 + 5,470 (estimated Venezuelan parolees, November-December 2022, pursuant to the new migration enforcement process for Venezuelans)

- January 2023: 5,214 + 11,637 (Cuban, Haitian, Nicaraguan, and Venezuelan parolees) = 16,851

- February 2023: 28 + 22,755 (Cuban, Haitian, Nicaraguan, and Venezuelan parolees) = 22,783

- Afghan parolees: 75,898

- Ukrainian parolees (estimated grants of parole pursuant to DHS’s Uniting for Ukraine progam, since May 2022): 119,546

(My colleague Andrew Arthur provided invaluable assistance to me in the derivation of these estimates.)

The Welfare Thoroughfare

PRWORA provides (with some exceptions) that “an alien who is not a qualified alien ... is not eligible for any Federal public benefit.” Who is a “qualified alien”? Illegal aliens are generally not, nor are aliens in the U.S. on temporary visas. The categories of aliens qualified to be “qualified” primarily encompass lawful permanent residents, refugees, and asylees, but also include “an alien who is paroled into the United States ... for a period of at least 1 year”. (Emphasis added.)

Qualified aliens generally have to meet special eligibility requirements for the most important federal welfare programs, in addition to meeting the eligibility standards for U.S. citizens:

- In general, qualified aliens are eligible for food stamps — the Supplemental Nutrition Assistance Program (SNAP, formerly known as food stamps) — “who ha[ve] resided in the United States with a status within the meaning of ... ‘qualified alien’ for a period of 5 years or more beginning on the date of the alien’s entry into the United States”. However, with respect to qualified alien parolees, those under 18 years of age are immediately eligible, as are those who meet one of three “military-related” tests: they are 1) on active duty in the Armed Forces (other than for training), 2) veterans who have been honorably discharged and who have completed the shorter of 24 months of continuous active duty or the full period for which they were called or ordered to active duty, or 3) the spouses and unmarried dependent children of such service members or veterans, or unremarried surviving spouses.

- In general, qualified aliens are eligible for Medicaid at the option of the state in which they reside after the “period of 5 years beginning on the date of alien’s entry into the United States with a status within the meaning of ... ‘qualified alien’”. However, with respect to “qualified” parolees, those who meet a “military-related” test are immediately eligible.

- In general, qualified aliens are eligible for the State Child Health Insurance Program (SCHIP) at the option of the state in which they reside after the “period of 5 years beginning on the date of alien’s entry into the United States with a status within the meaning of ... ‘qualified alien’”. However, with respect to “qualified” parolees, those who meet a “military-related” test are immediately eligible, as are women during pregnancy and during the 60-day period beginning on the last day of the pregnancy, and persons under 21 years of age.

- In general, qualified aliens are eligible for the Temporary Assistance for Needy Families (TANF) program at the option of the state in which they reside after the “period of 5 years beginning on the date of alien’s entry into the United States with a status within the meaning of ... ‘qualified alien’”. However, with respect to “qualified” parolees, those who meet a “military-related” test are immediately eligible.

- In general, qualified aliens are eligible for programs funded by Social Security block grants at the option of the state in which they reside after the “period of 5 years beginning on the date of alien’s entry into the United States with a status within the meaning of ... ‘qualified alien’”. However, with respect to “qualified” parolees, those who meet a “military-related” test are immediately eligible. What do Social Security block grants involve? Federal law provides that:

For the purposes of consolidating Federal assistance to States for social services into a single grant, increasing State flexibility in using social service grants, and encouraging each State, as far as practicable under the conditions in that State, to furnish services directed at the goals of—

(1) achieving or maintaining economic self-support to prevent, reduce, or eliminate dependency;

(2) achieving or maintaining self-sufficiency, including reduction or prevention of dependency;

(3) preventing or remedying neglect, abuse, or exploitation of children and adults unable to protect their own interests, or preserving, rehabilitating or reuniting families;

(4) preventing or reducing inappropriate institutional care by providing for community-based care, home-based care, or other forms of less intensive care; and

(5) securing referral or admission for institutional care when other forms of care are not appropriate, or providing services to individuals in institutions,

there are authorized to be appropriated for each fiscal year such sums as may be necessary to carry out the[se] purposes.

- In general, qualified aliens are not eligible for Supplemental Security Income (SSI). However, with respect to “qualified” parolees, those who meet a “military-related” test are eligible.

There are two bits of ambiguity here regarding parolees. First, since parolees are only considered qualified aliens if they are paroled into the U.S. for a period of at least a year, it would seem that, for them, the 5 year waiting period is actually a 6 year waiting period. The 5 year clock wouldn’t start ticking until an alien has been in parole status in the U.S. for a year. But, this is not how federal agencies have interpreted the waiting period. In, 1997, the Department of Justice issued Interim Guidance on Verification of Citizenship, Qualified Alien Status and Eligibility Under Title IV of the Personal Responsibility and Work Opportunity Reconciliation Act of 1996, and that guidance states that the documentary evidence to demonstrate status as a qualified parolee is “Form I–94 [arrival/departure record] with stamp showing admission for at least one year under section 212(d)(5) of the INA. (Applicant cannot aggregate periods of admission for less than one year to meet the one-year requirement.)”. Thus, an alien becomes qualified as soon as he or she gets a stamp showing admission for at least a year -- they don't have to wait around for a year in the U.S. before being considered qualified. And SNAP regulations, for example, specify that qualified aliens “must be in a qualified status for 5 years before being eligible to receive SNAP benefits”.

Second, as mentioned, qualified aliens are eligible for food stamps “who ha[ve] resided in the United States with a status within the meaning of ... ‘qualified alien’ for a period of 5 years or more beginning on the date of the alien’s entry into the United States”. The language of the five-year waiting period for the other federal programs is a bit different — after the “period of 5 years beginning on the date of alien’s entry into the United States with a status within the meaning of ... ‘qualified alien’”. (Emphasis added.)

What does “entry” mean? Prior to the enactment of the Illegal Immigration Reform and Immigrant Responsibility Act of 1996, the INA defined “entry” as “any coming of an alien into the United States, from a foreign port or place or from an outlying possession, whether voluntary or otherwise”. While no longer defined in the INA, the term now generally has the same meaning.

I read the non-food stamp waiting period language as requiring that an alien have been in a status within the meaning of “qualified alien” at the time of their entry into the U.S. The legislative history supports my interpretation. The House Budget Committee’s report on H.R 3734, the “Welfare and Medicaid Reform Act”, the bill that was to be enacted as PRWORA, states that the five-year waiting period language (identical to that in PRWORA as enacted) “provides that an alien who enters the U.S. as a qualified alien on or after the date of enactment of this Act is not eligible for any Federal means-tested public benefit for a period of 5 years beginning on the date of the alien’s entry into the U.S.” (Emphasis added.) Thus, a parolee who enters the U.S. illegally, is apprehended, and is then released from detention pursuant to a grant of parole, can never satisfy the five-year waiting period because they were not the beneficiary of a grant of parole (and thus a qualified alien) at the time they entered the U.S. Such a parolee can never become eligible for federal means tested benefits subject to the five-year waiting period (unless qualifying for some statutory exception). However, I am not aware that this issue has ever been litigated.

Incidentally, you might be asking “What about all the other federal welfare programs?” Well, that is a sore subject with me. The Clinton administration figured out a (quite questionable) way to justify exempting other programs from PRWORA’s limitations on the eligibility of qualified aliens, and the Clinton exemptions have never been altered. I’ll let the U.S. Department of Health and Human Services explain:

-

HHS is defining “Federal means-tested public benefit” to apply only to benefits provided by Federal means-tested, mandatory spending programs, and not to any discretionary spending programs.

-

Early versions of PRWORA contained a definition of “Federal means-tested public benefit” that could have encompassed benefits provided by both discretionary spending programs and mandatory spending programs. ... During debate over the bill in the Senate, a member of the Senate raised a point of order pursuant to the Byrd Rule, and the definition was struck. The Senate Parliamentarian upheld the Byrd Rule objection, the Senate did not appeal the ruling, and PRWORA was ultimately enacted without defining the term. PRWORA was subject to Section 313 of the Congressional Budget Act of 1974, also known as the “Byrd Rule,” because it was enacted as a budget reconciliation bill. Under the Byrd Rule, a Senator may raise a point of order to strike or prevent the incorporation of “extraneous” material. A provision in a reconciliation bill will be considered “extraneous” and subject to a point of order if, among other things, “it produces changes in outlays or revenues which are merely incidental to the non-budgetary components of the provision[”]. ... Therefore, to the extent the definition of “Federal means-tested public benefit” included benefits provided by discretionary spending programs, it was subject to a Byrd Rule objection.

The Clinton administration’s Department of Agriculture and Social Security Administration reached identical conclusions. Inside baseball? Sure, but with huge ramifications in the outside world. This legislative legerdemain to a significant extent defanged PRWORA. At the time (1997), I believed the Clinton administration’s rationale to be specious. With a bit of chutzpah, I requested a meeting with Attorney General Janet Reno to make my case. AG Reno actually agreed to come to the Hill to discuss the matter with me. Of course, I didn’t persuade her, but I was — and remain to this day — deeply impressed that she actually took time out of her day to sit down with me. In any event, that is another story for another day.

Parole Payday

So, how much will all this cost American taxpayers? I should first point out that as soon as parolees, or any aliens for that matter, have U.S. born-children, those children are U.S. citizens courtesy of birthright citizenship and eligible for federal welfare benefits to the same extent as any other similarly situated U.S. citizens. The benefits check? It will go directly to the parents or legal guardians, whether or not they are eligible for benefits themselves. As to federal housing benefits, as long as one member of a household is eligible, the whole household can receive benefits.

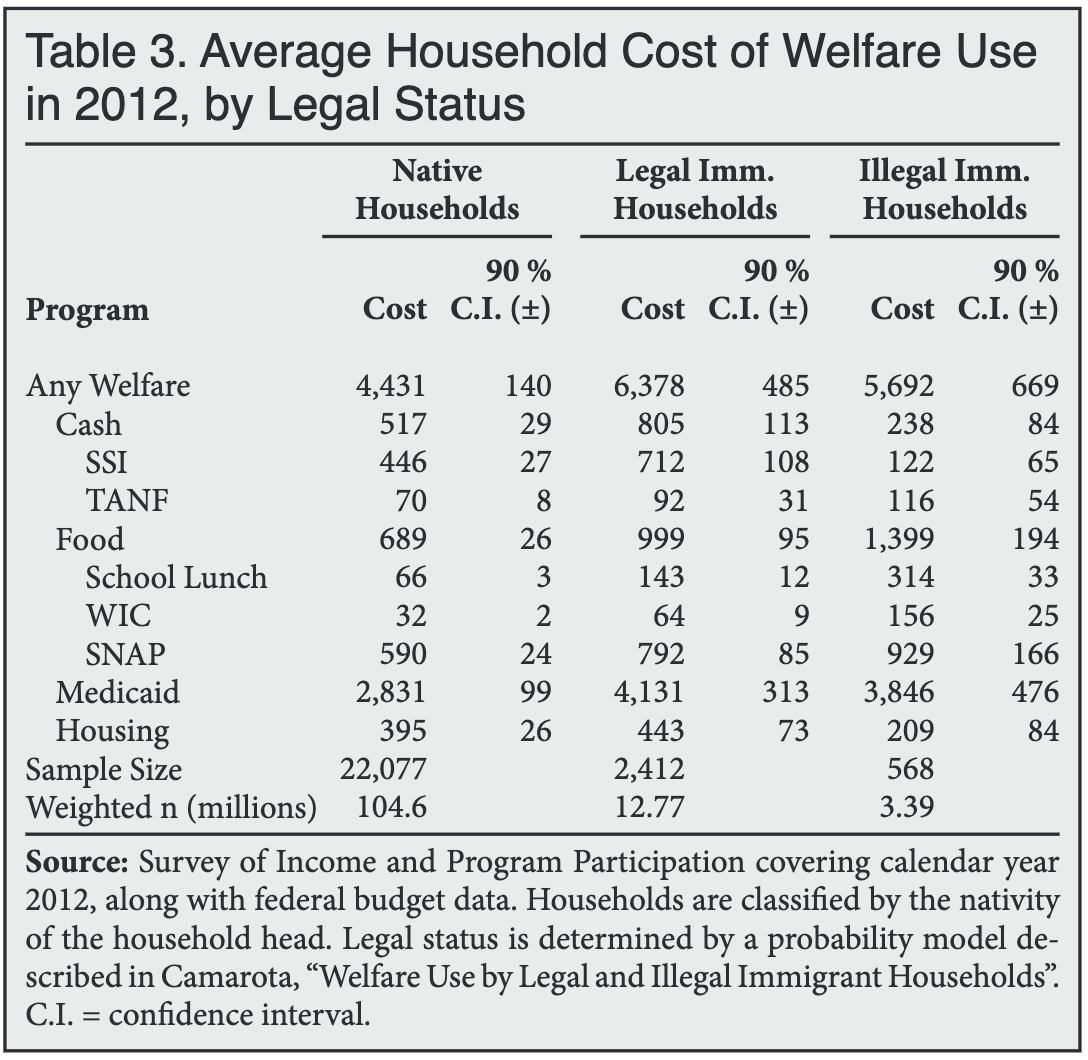

Obviously, the longer parolees reside in the U.S., the more likely they are to have U.S. citizen children. My colleague Jason Richwine estimates that households headed by illegal aliens consume on average $5,692 worth of federal welfare benefits each year, driven largely by the presence of U.S.-born children. The key table from that 2016 report:

|

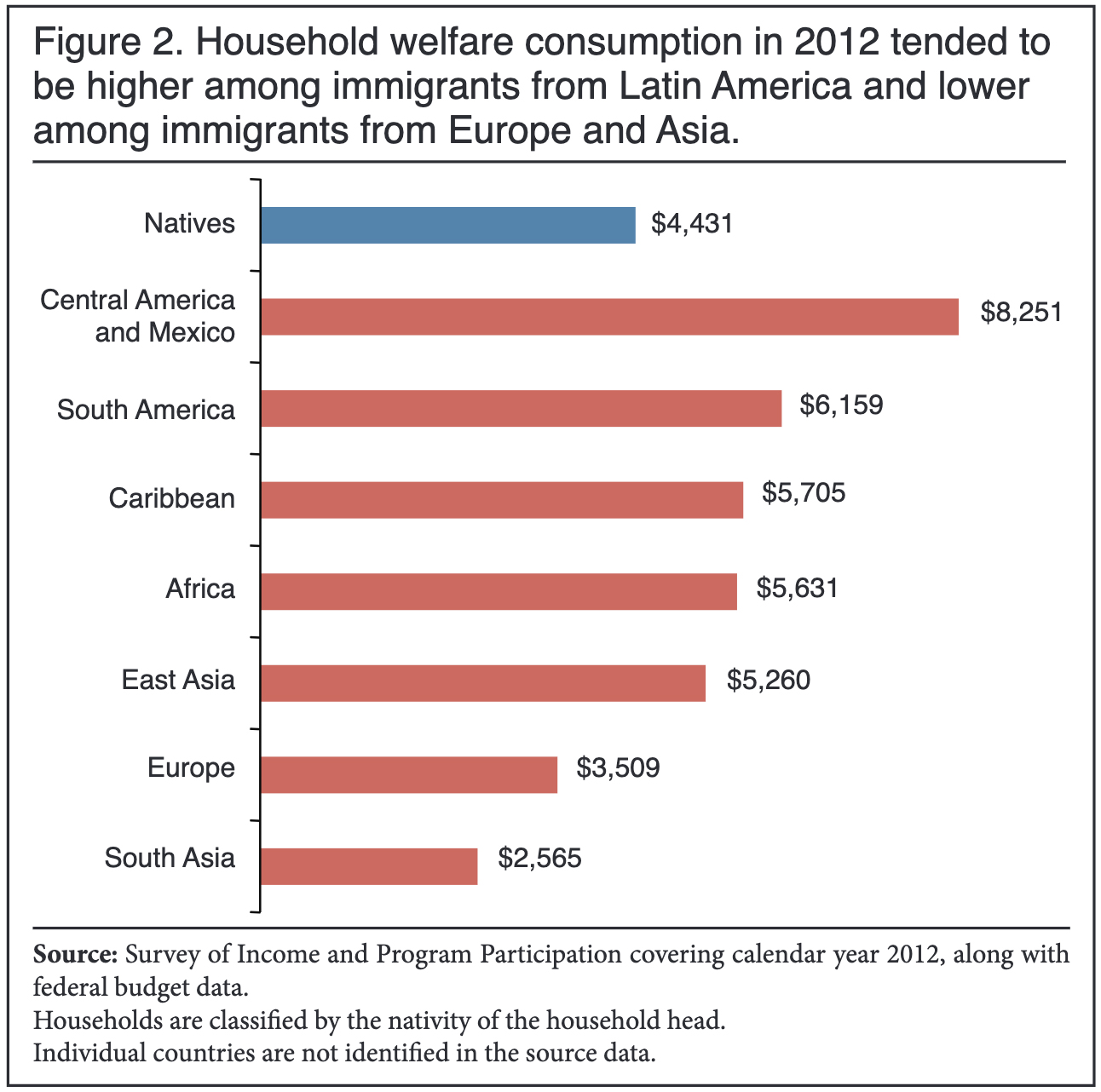

That figure is likely higher for households headed by illegal aliens from Central America and Mexico, as Richwine estimates that household consumption of federal welfare programs is higher among immigrants as a whole from those areas. From that same report:

|

As my colleague Steven Camarota reports in the following table from a 2015 report, households headed by illegal aliens are more than twice as likely to use federal welfare programs as are households headed by natives:

|

It is reasonable to assume that parolees with U.S.-born children receive a similar level of federal welfare benefits before they become eligible themselves for various federal programs.

It is true that aliens apprehended along the border and released on parole by the Biden administration would enjoy the same access to such benefits (on behalf of their children) if they had been released through a non-parole mechanism. And it is true that aliens ushered into the U.S. through Biden administration categorical parole programs would enjoy the same access to this level of benefits had they entered illegally. However, many would never have tried to enter illegally or would have been unsuccessful in their attempts, had parole not been available and had the Biden administration not dismantled Trump-era border security programs such as the Migrant Protection Protocols.

In any event, let’s focus on the federal welfare benefits for which aliens will become eligible only as a consequence of their becoming “qualified aliens” on the basis of grants of parole. How much is/will be the cost to taxpayers? To answer this question, we need a sense of how long parolees will remain in such status in the U.S.

Of course, aliens in a parole status for less than a year (i.e., those granted parole consistent with Congress’ intent) will not receive a “parole payday”. And for those in parole status for a year or more, most, but not all, of the payday will only come to those who are still parolees five years after getting their stamps. Additionally, some parolees will be able to adjust status to lawful permanent residence, such as by marrying a U.S. citizen, or for Cubans, by being physically present in the U.S. for a year.

For those aliens invited into the U.S. through Biden administration grants of parole, DHS can hand out parole extensions — “re-parole” — at its discretion. As U.S. Citizenship and Immigration Services puts it:

Presumably, the Biden administration will hand out extensions for the asking. Post-Biden administrations might or might not do so.

As to those parolees who were apprehended at the border and placed into removal proceedings, the Departments of Homeland Security and Justice recently reported that “[e]xcluding in absentia orders, the mean completion time for [Executive Office for Immigration Review] EOIR cases completed in FY 2022 was 4.2 years.” The departments elaborate:

[T]he process for those who establish a credible fear is quite lengthy, with half of all cases taking more than four years to complete, and in many cases much longer. Indeed, 39 percent of all [southwest border] SWB credible fear referrals to EOIR from FY 2014 to FY 2019 remain in EOIR proceedings today. As of FY 2022 year-end, more than a quarter (26 percent) of EOIR cases resulting from SWB encounters making credible fear claims from as long ago as FY 2014 remained in proceedings, one-third (33 percent) of EOIR cases resulting from FY 2016 encounters remained in proceedings, and almost half (48 percent) of EOIR cases resulting from FY 2019 encounters remained in proceedings.

For those ordered removed, either in person or in absentia (for those who don’t show up for their removal proceedings), DHS will presumably rescind their grants of parole (“when the purposes of such parole shall, in the opinion of the [Secretary], have been served the alien shall forthwith return or be returned to the custody from which he was paroled”). Those granted asylum will become eligible for federal welfare benefits on an even more privileged basis than are parolees.

So, at an incredible average of more than four years (“and in many cases much longer”) between an apprehended alien being issued a notice to appear (NTA) for removal proceedings and an immigration judge issuing a decision, many parolees will indeed make it to their parole payday.

And the timeframe is likely to only continue to lengthen. The Transactional Records Access Clearinghouse at Syracuse University (TRAC) reports that the number of pending asylum cases in immigration court has risen from 105,919 at the end September 2012 to 787,882 at the end of November 2022 (an increase of 644 percent), and that the subset of pending defensive asylum cases (those raised as a defense to removal in removal proceedings) has increased over this time period from 32,243 to 606,738 (an increase of 1782 percent). TRAC explains that:

These rising case numbers, however, still underestimate the actual total backlog of asylum seekers in the United States awaiting their hearings. For asylum seekers who are put into the deportation process, their deportation case begins before their asylum case begins. The formal application for asylum is usually filed months after their NTA is issued and after the case is added to the Immigration Court, typically due to the time needed to get an attorney and assemble what can often be quite complex cases. But from a data tracking perspective, it is only with the filing of an asylum application that a case can be identified as part of the asylum backlog. If the number of asylum seekers are rising, the asylum backlog count lags behind the number of asylum seekers who have entered the Court’s workload.

Then, TRAC explains the difficulty of estimating how long it will take to complete removal proceedings in the future:

Only about four out of ten (43%) individuals in the current asylum backlog have an actual individual proceeding scheduled to hear the evidence on the merits of that asylum seeker’s claims.

The remaining majority of cases fall into one of two groups. For 35 percent of those waiting in the asylum backlog, the hearing scheduled is still at the “master calendar” stage. For these initial hearings, a group of individuals are summoned to appear together where they are advised of their rights and procedures, the charges and factual allegations contained in the [NTA] are explained, and cases are sorted as to what comes next. More than one of these master calendar hearings may occur if an individual needs more time to find an attorney to represent them, or an attorney once found, needs time to secure documents and obtain testimony to support the asylum application. Only after these master calendar hearings come to a conclusion, is an individual hearing scheduled on the asylum seeker’s claims. Only one hearing is set at any point in time. Thus, for those scheduled for master calendar hearings, no information is available on just when the actual merits hearing eventually may occur.

On the remaining 22 percent of asylum seekers waiting in the backlog, no hearing of either kind is currently scheduled. These don’t tend to be newly arriving cases. Those without any scheduled hearing have already been waiting an average of 1,092 days, or 3 years.

The percentage of asylum seekers with no next hearing scheduled has grown. For example, during FY 2020 only 12 percent of cases in the backlog had no hearing scheduled as compared with 22 percent now.

...

Average wait times are of necessity based upon the recorded times of the next scheduled hearing for each case. Where many cases do not even have their asylum hearing scheduled, clearly the resulting estimate is a mere “guesstimate” at best.

But that is not the end of the matter. To make things even worse, the Biden administration has not even been issuing NTAs to many apprehended aliens, but rather has been telling them to show up at a U.S. Immigration and Customs Enforcement (ICE) office at some point in the future to receive an NTA. And that is just to let them know when to show up at immigration court for the initiation of their proceedings. As U.S. District Court Judge T. Kent Wetherell II explained in March, the resulting backlog in NTAs not yet issued will add additional years to the process:

-

[A]s of April 26, 2022, there had been over 226,000 aliens released under “prosecutorial discretion” under the [Notice to Report] NTR and Parole+ATD [Alternatives to Detention] policies. More than 110,000 of those aliens had not been issued NTAs and more than 66,000 were outside the period that they were supposed to have reported to ICE to be issued an NTA.

ICE officials estimated that it would take nearly 3 years ... to clear the “backlog” and issue NTAs to these 110,000 aliens if the Parole+ATD policy was stopped at that point.

-

[T]his backlog only accounts for the time needed to begin removal proceedings — not the additional time required to complete those proceedings and remove aliens. ... [T]he backlog created by Parole+ATD will take decades to overcome.

It’s 2023. How large is the backlog now? NBC News reported last month that:

In late March 2021 ... [U.S. Customs and Border Protection] CBP began releasing migrants with what is known as a “Notice to Report,” telling them to report to an [ICE] office, rather than a “Notice to Appear,” which instructs migrants when to appear in court to determine whether they will be deported or given protections to remain legally in the U.S.

But that process proved problematic, as reports emerged that many migrants were not showing up at ICE offices to receive court dates.

So ICE began a new program in July 2021 ... known as . . . Parole Plus ATD. ... [which] allowed migrants to be released without charging documents while their whereabouts were tracked with ankle monitors, by checking in on an app or telephonically.

Between late March 2021 and late January 2023, more than 800,000 migrants were released on Notices to Report or Parole Plus ATD. About 214,000 of them were eventually issued charging documents with court dates, according to data obtained by NBC News, meaning that roughly 588,000 did not know when or where to report for their asylum hearings.

And how long is the backlog now? In some cases, DHS is telling parolees to show up to receive an NTA a decade from now! Steven Nelson recently reported in the New York Post that:

-

The backlog means migrants may have to wait almost a decade just to enter the immigration court process — which is beset by further delays stretching out years, sources said.

-

New York City’s [ICE] office is “fully booked through October 2032” for appointments to process migrants released at the southern border, according to an official document exclusively reviewed by The Post.

-

The document reviewed by The Post lists the “Top 10 Parole/NTR Appointment Backlog Locations” and said that as of Feb. 13, there were 39,216 non-citizens with appointments at ICE’s New York City office — making it the most clogged jurisdiction in the country.

The second-most backlogged ICE office is in Jacksonville, Fla., which was “mostly booked” for appointments through June 2028 with 2,686 migrants in line.

Third-place Miramar, Fla., is “fully booked” through January 2028 with 24,747 migrants who have appointments.

Rounding out the top 10 were offices in Atlanta (“mostly booked” through January 2027), San Antonio (“fully booked” through February 2027), Mount Laurel, NJ (“fully booked” through May 2026), Chicago (“mostly booked” through February 2026), Baltimore (“mostly booked through” January 2026), Milwaukee (“fully booked” through February 2026) and Indianapolis (“fully booked” through January 2026).

-

ICE, given more than a week to comment by The Post, neither disputed the accuracy of the reported backlog figure nor contradicted sources’ contention about what it meant.

So, given that a large number of Biden parolees seem destined to remain in such status for many years to come and thus reap the benefit of a parole payday, can we estimate how much the average payday is worth? In essence, the payday is equivalent to the value of federal welfare benefits that parolees will receive, generally after their fifth year as parolees, over and above those received by all aliens who have recently arrived.

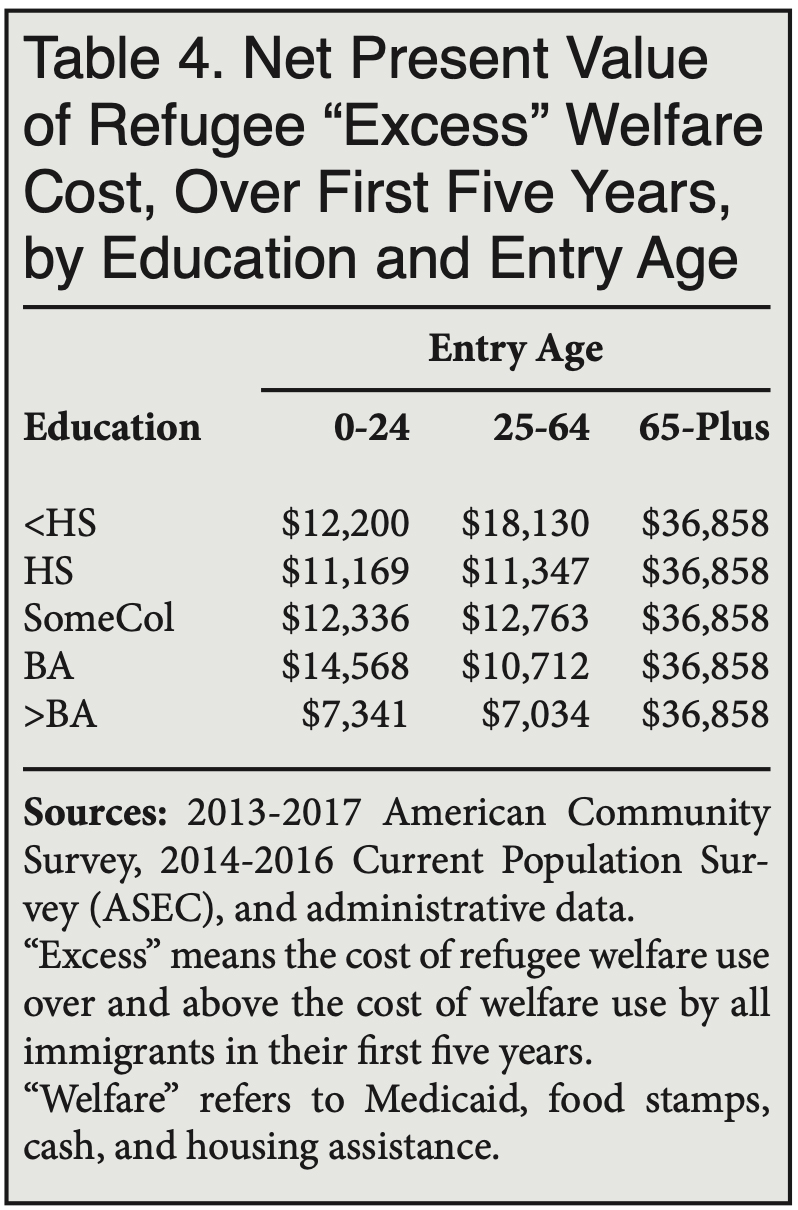

A rough estimate can be derived by looking at the net present value of refugees’ “excess” welfare costs during their first five years in the U.S. My colleagues Jason Richwine, Steven Camarota, and Karen Zeigler did just this:

-

[R]efugees are immediately eligible for federal welfare programs, while most other immigrants must be legal permanent residents for five years before accessing benefits. The “Plus Five-Year Welfare Costs” ... includes the added cost of Medicaid, cash assistance, food stamps, and housing benefits that refugees consume in excess of what the average immigrant consumes within the first five years.

-

To ensure that we are capturing only added costs associated with refugee status, we subtract the welfare costs associated with all recent immigrants. ... We sum these excess costs over five years of welfare eligibility, discounting at 3 percent.

The results, as calculated by Richwine, Camarota, and Zeigler, are as follows:

|

So, the “excess” costs range from a present value of about $7,000 over five years for a refugee who came to the U.S. between the ages of 25 and 64 with an education level of more than a bachelor’s degree, to a present value of $36,858 over five years for a refugee who came at the age of 65 or higher. For refugees who came to the U.S. before age 65, the estimated “excess” welfare cost is dependent on education level. Camarota concluded in 2017 that:

Because illegal border-crossers are overwhelmingly from Mexico and the rest of Latin America, we use the education level of illegal immigrants from Latin America to estimate border-crossers' education profile. My analysis of illegal immigrants from Latin America indicates that they have the following education: 57 percent, less than high school; 27 percent, high school only; 10 percent, some college or associate's degree; 4 percent, bachelor's only; and 2 percent, more than a bachelor's.

Using the educational data that Camarota reported in 2017, the average net present value for “excess” federal welfare costs for refugees arriving at ages 25-64 is $15,243 over five years, or about $3,000 per year. If we were to use this value as an estimate of the parole payday for parolees once they have been in that status for five years, the yearly cost of President Biden’s parole bender will be about $3 billion a year per million parolees. The first Biden parolees will begin receiving their parole paydays in January 2026.

Conclusion

It is one thing to make certain federal welfare programs available to all aliens, including illegal aliens. Under PRWORA, all aliens are eligible for:

-

Medical assistance ... for care and services that are necessary for the treatment of an emergency medical condition.

-

Short-term, non-cash, in-kind emergency disaster relief.

-

Public health assistance ... for immunizations with respect to immunizable diseases and for testing and treatment of symptoms of communicable diseases whether or not such symptoms are caused by a communicable disease.

-

Programs, services, or assistance (such as soup kitchens, crisis counseling and intervention, and short-term shelter) ... which (i) deliver in-kind services at the community level, including through public or private nonprofit agencies; (ii) do not condition the provision of assistance, the amount of assistance provided, or the cost of assistance provided on the individual recipient’s income or resources; and (iii) are necessary for the protection of life or safety.

But to direct billions of taxpayer dollars a year specifically to persons who would for all intents and purposes be illegal aliens, were it not for the abusive parole practices of the Biden administration, is quite another thing.

Of course, the optimal outcome would be for the Supreme Court to declare unlawful the Biden administration’s misadministration of the parole power or for Congress to clarify that the executive branch, going forward, may not engage in such abuse of the power. But, at the very least, Congress should end the perverse result of current law — rewarding otherwise illegal aliens granted parole by giving them billions of dollars a year in federal welfare benefits for which most legal aliens (other than lawful permanent residents, refugees, and asylees) are ineligible.

The main impact of the parole paydays for Biden parolees won’t hit for about three years. Congress might well want to consider in the interim amending PRWORA to remove parolees from the definition of “qualified aliens”.

And Congress might well want to consider amending PRWORA to add back the definition of federal means-tested public benefit program that the Senate dropped (a “Byrd dropping”). This would fulfill the goal of PRWORA’s drafters to make nonqualified aliens ineligible for almost all federal means-tested benefits and to subject qualified aliens to the five-year test for all federal means-tested benefits (unless specifically exempted).

Oh, and if Congress does not act, certain states (you know who you are) might want to challenge the legality of considering long-term parolees who did not enter the U.S. in that status to have met the five-year test for eligibility for many federal welfare benefits.