Download a PDF of this Backgrounder.

Steven A. Camarota is the director of research and Karen Zeigler is a demographer at the Center.

There is significant literature, including some new research on Covid-19, indicating that overcrowded housing increases the spread of communicable diseases. Using a standard definition, we examine overcrowding among immigrant workers (legal and illegal) and native-born workers based on the Census Bureau’s 2018 American Community Survey (ACS). We find that 14.3 percent of immigrant workers live in overcrowded housing, four times the 3.5 percent for native-born workers. Due to their high rates of overcrowding, immigrants account for nearly half of all workers living in overcrowded households. And, in a number of occupations, they are an outright majority. Many of these occupations are thought to be essential during the Covid-19 pandemic.

Many factors having nothing to do with immigration have contributed to the Covid-19 pandemic. Nonetheless, the evidence indicates that overcrowding facilitates its spread and immigration has added enormously to overcrowded conditions in many parts of the country. Therefore, reducing immigration levels in the future would reduce overcrowding over time. Moreover, since overcrowding declines with higher wages, less immigration would also be helpful by putting upward pressure on wages for existing workers — immigrant and native-born alike. Other policy options that increase wages, such as raising the minimum wage, should also be considered.

Among the findings:

- Immigrant workers are four times as likely as native-born workers to live in overcrowded housing. As a result, they comprise 17 percent of all workers, but 46 percent of workers living in crowded conditions.

- Immigrant workers make up a large share of workers living in overcrowded housing in many sectors thought to be essential during the Covid-19 epidemic, including those in production, healthcare support, transportation and moving, food preparation, sales, and farming.

- In specific occupations within these sectors, immigrants (legal and illegal) comprise a disproportionate share of workers in overcrowded conditions. For example:

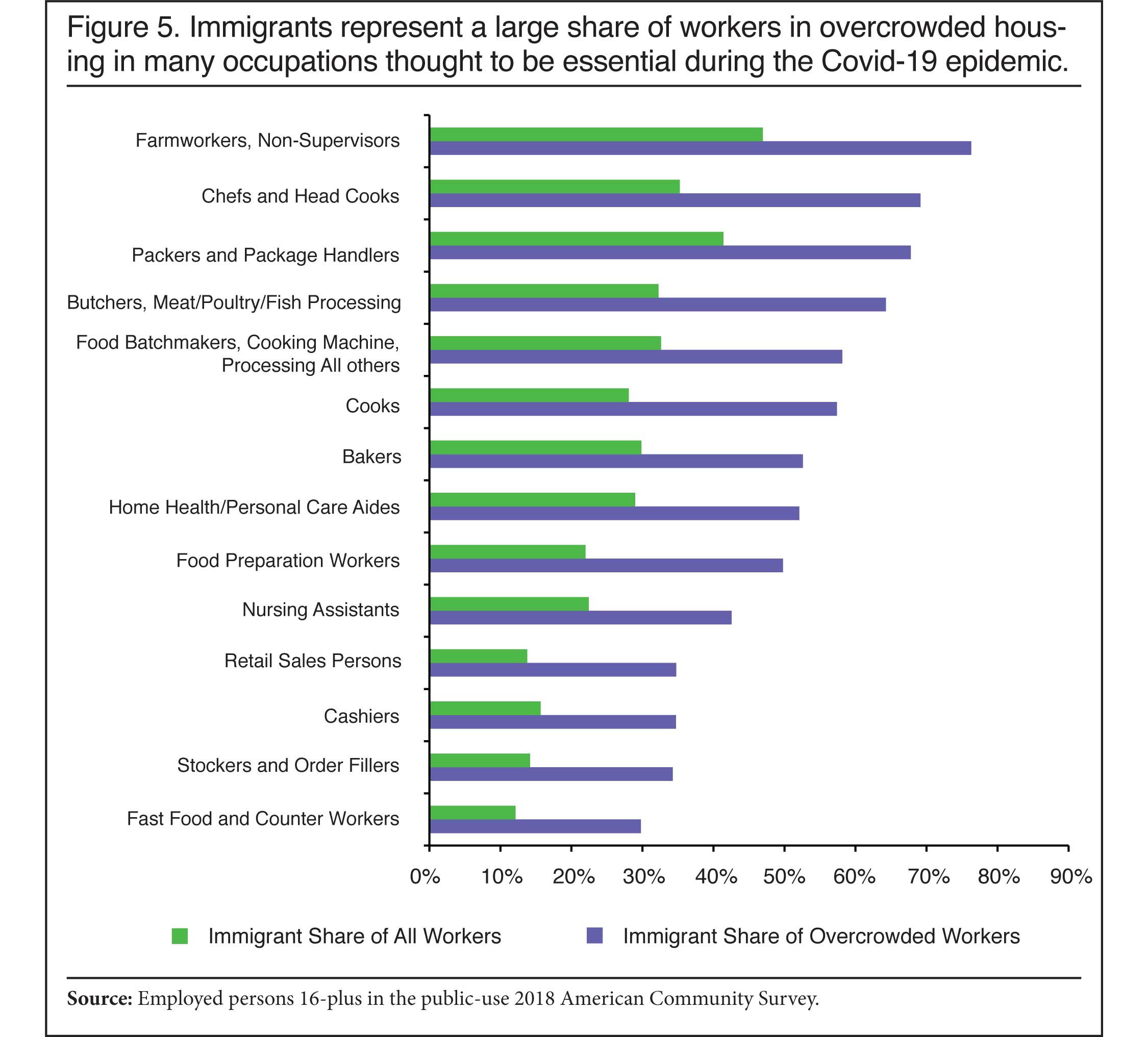

- Immigrants are 47 percent of farmworkers, but 76 percent of farmworkers in crowded housing.

- Immigrants are 41 percent of packers, but 68 percent of packers in crowded housing.

- Immigrants are 32 percent of butchers/meat processors, but 64 percent of such workers in crowded housing.

- Immigrants are 28 percent of cooks, but 57 percent of cooks in crowded housing.

- Immigrants are 30 percent of bakers, but 53 percent of bakers in crowded housing.

- Immigrants are 29 percent of health care aides, but 52 percent of health care aids in crowded housing.

- Immigrants are 22 percent of food prep. workers, but 50 percent of prep. workers in crowded housing.

- In 24 states immigrants account for more than one-third of workers in overcrowded households.

- Overall, immigrants are much more likely than native-born workers to work in low-wage jobs, reside in urban areas, and live in larger households; this partly explains why they are much more likely to live in overcrowded conditions.

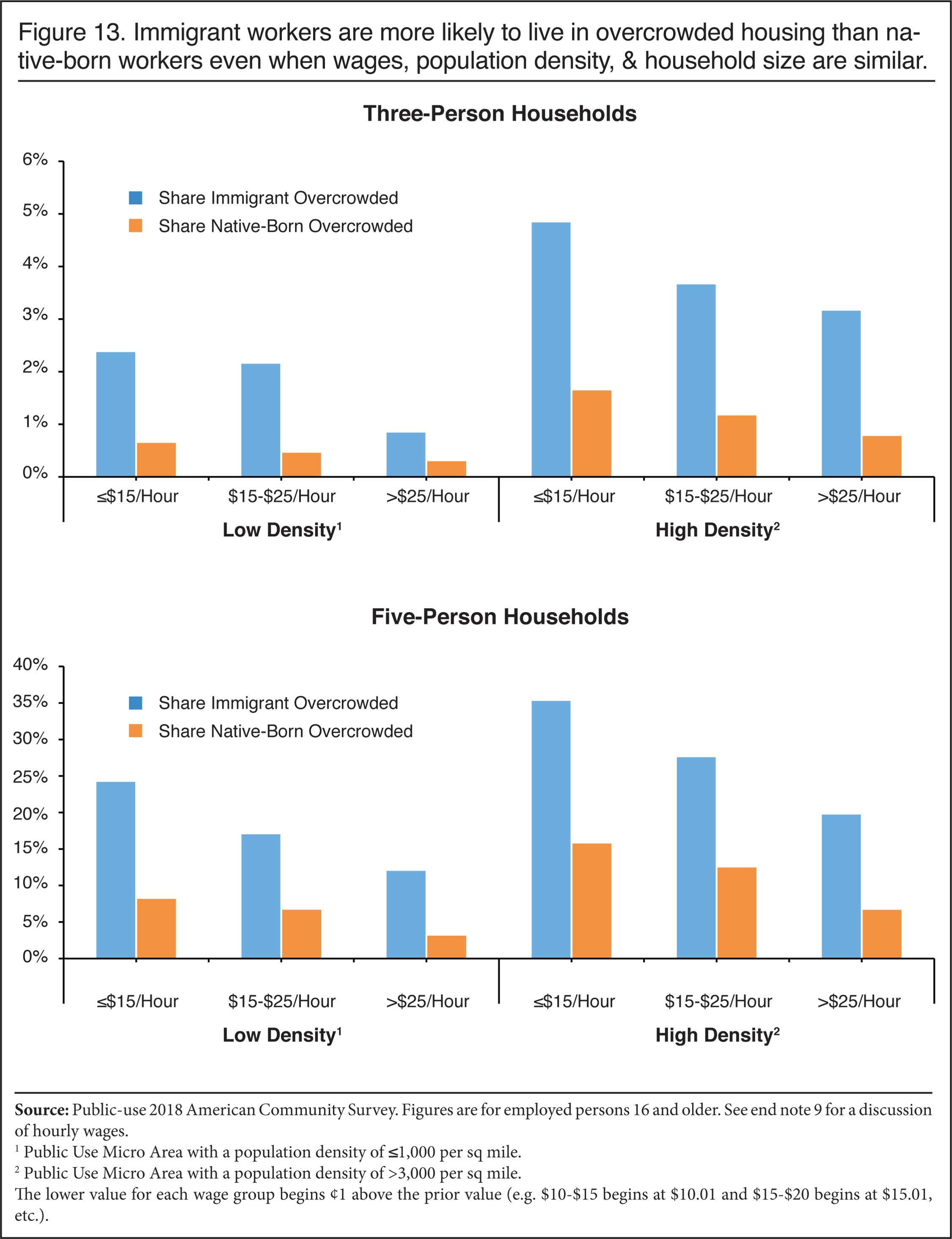

- However, even taking into account wages, household size, and the population density where they live, immigrants are still much more likely to reside in overcrowded housing. For example, 35 percent of immigrant workers who live in an urban area, have five members in their household, and earn $10 an hour or less live in an overcrowded home, compared to 16 percent of natives who live in the same conditions.

- Cultural preferences about personal space and immigrants’ desire to send money home rather than spend it on housing likely help to explain immigrants’ higher rates of overcrowding compared to the native-born, even when controlling for several factors at once. But these factors are not the focus of the analysis and would require more research to fully address.

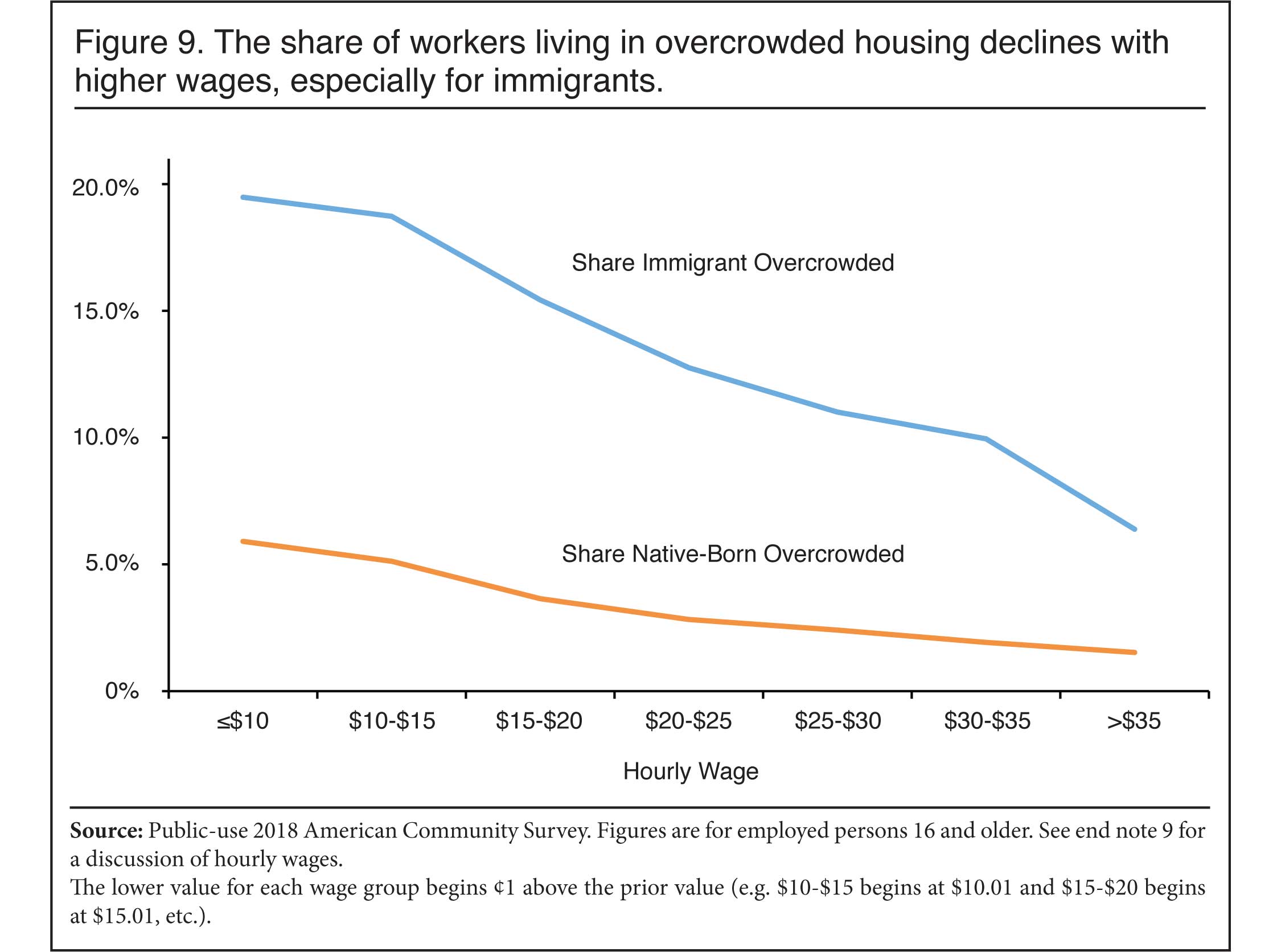

- Despite the differences between immigrants and natives, it is clear that immigrants, as well as the native-born, have much lower rates of overcrowding the higher their wages. Of immigrants (legal and illegal) earning $15 an hour or less, 19 percent live in overcrowding housing; for those earning at least $35 an hour, the rate is just 6 percent.

- Paying higher wages to workers would almost certainly reduce overcrowding. Curtailing the future flow of legal and illegal immigrants into the country would help raise wages and reduce the direct impact immigration has on crowding. Other policies that raise wages should also be considered, such as increasing the minimum wage and strengthening labor unions.

Estimates by legal status:

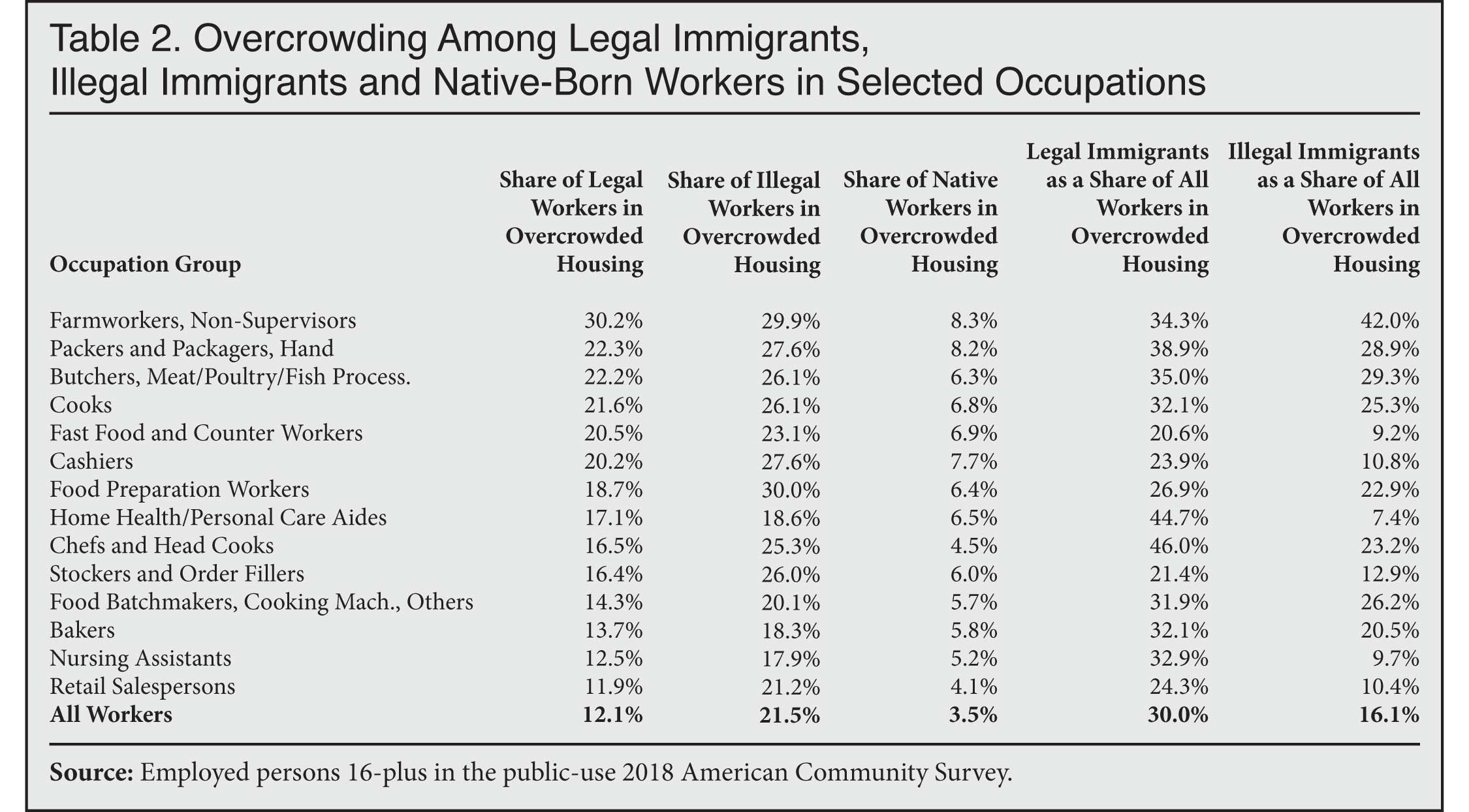

- We estimate that the share of illegal immigrant workers (21 percent) in overcrowded housing is about five times as high as the share of native-born workers (4 percent). At 12 percent, the share of legal immigrant workers in overcrowded housing is three times that of the native-born.

- Because overcrowding is so much more common among legal and illegal immigrant workers, they comprise a disproportionate share of those living in overcrowded homes:

- Legal immigrants are 13 percent of all workers, but 30 percent of all workers in overcrowded conditions.

- Illegal immigrants are 4 percent of all workers, but 16 percent of all workers in overcrowded conditions.

Introduction

There are several possible measures of what constitutes an overcrowded household.1 When using Census Bureau data, it is most common to define a household as overcrowded when there is more than one person per room living in a housing unit, excluding bathrooms, porches, balconies, foyers, halls, or unfinished basements.2 Except where indicated, this analysis uses the public-use files of the American Community Survey (ACS), which is collected by the Census Bureau, and follows this common definition. We exclude those residing in group quarters such as prisons, nursing homes, and college dorms. We use the terms “overcrowded” and “crowded” throughout this report interchangeably.

Overcrowded residential housing is a problem for a number of reasons. Most relevant to the current situation, there is significant literature on the role that overcrowded housing can play in facilitating the spread of communicable diseases, including in first-world countries.3 A number of studies have specifically examined the role of overcrowding in the United States, defining overcrowding in the same manner as this analysis. These analyses all show that crowded conditions is one factor that increases the risk of being hospitalized by the seasonal flu.4

There have also been several new analyses done since the current epidemic began, showing a strong link between the incidence of Covid-19 and overcrowded housing.5 An analysis by the Donahue Institute at the University of Massachusetts (UMDI) found that overcrowded housing was "the most indicative measure of Covid-19 spread that UMDI observed". In addition to this research, a blog post for the Center for Immigration Studies by Jason Richwine and Steven Camarota also shows a correlation between the share of a county’s households that are overcrowded and Covid-19 infection rates.6 The relationship is especially strong in the nation’s largest counties, where estimates of immigration and overcrowding are the most statistically robust.

Since the Covid-19 outbreak began, major media outlets have been raising the concern that overcrowded housing can facilitate its spread.7 Covid-19 has caused significant outbreaks and shutdowns at warehouses and packaging and food processing facilities, including those run by Amazon and Walmart. In May and June of this year, the CDC reported that 111 meat and poultry processing facilities have had outbreaks of the disease and 24 shut down temporarily.8 In much of the analysis that follows, we focus on workers in food processing, packaging and storage facilities, and other jobs often thought to be essential during the Covid-19 outbreak. These jobs typically pay modest wages and, as we will see, many of the workers in such jobs live in crowded housing. In order to better understand overcrowding among workers, this analysis examines in detail crowding among immigrant and native-born workers. Immigrants, which the Census Bureau refers to as the “foreign-born”, are individuals who were not U.S. citizens at birth. They include naturalized citizens, legal permanent residents (green card holders), temporary visitors (primarily guestworkers and foreign students), and illegal immigrants, almost all of whom are captured in ACS data. Later in this report we provide our best estimate of overcrowding by legal status.

Findings

Wages

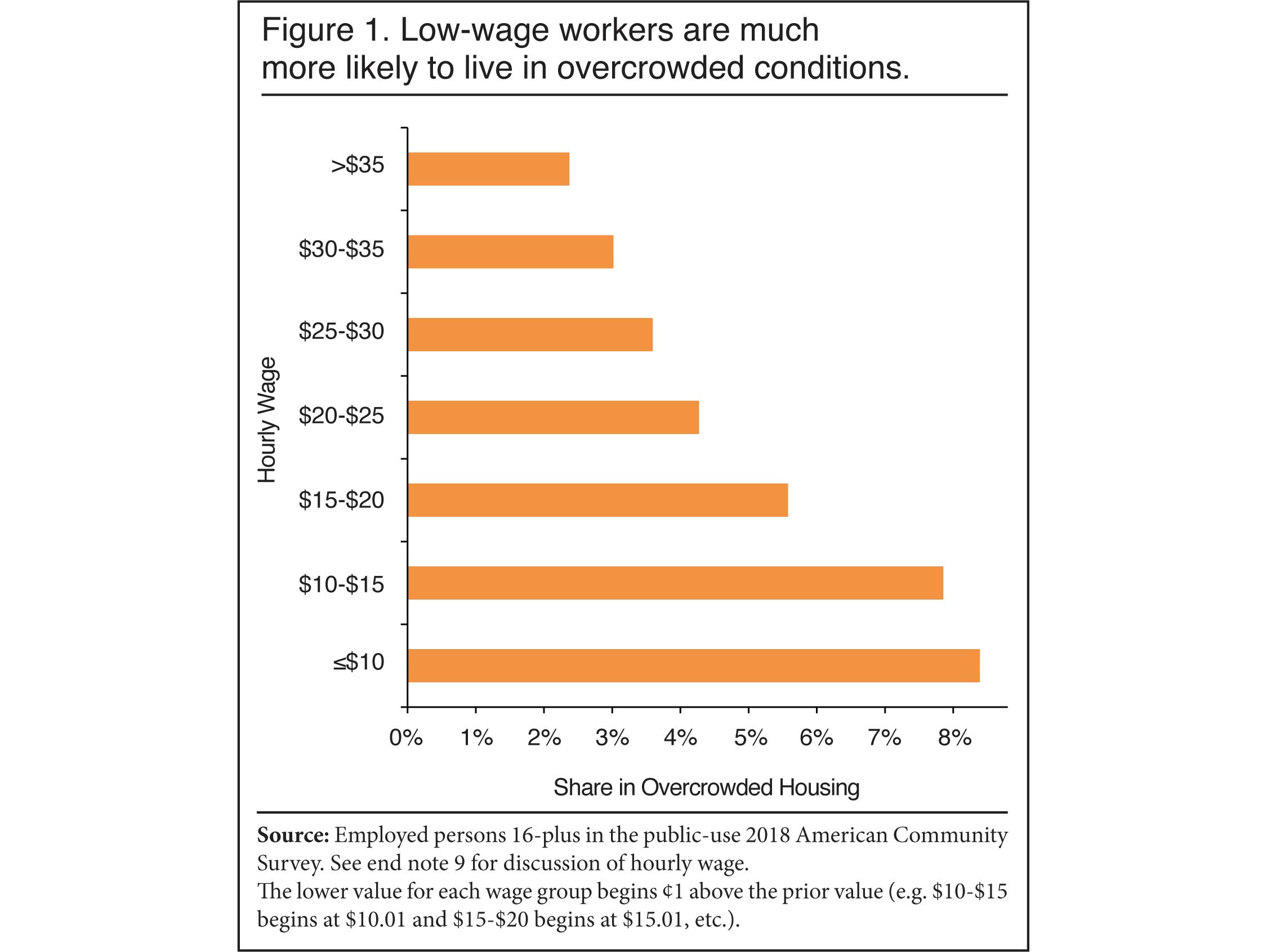

Figure 1 shows that overcrowding is clearly linked to wages, with the poorest workers being the most likely to live in overcrowded conditions.9 This of course makes sense as those with less income are more likely to struggle to find affordable housing. Because overcrowding is more common among those who have modest earnings, low-wage workers comprise the majority of those living in overcrowded households. In 2018, workers earning less than $10 an hour accounted for 18 percent of all workers but 28 percent of those living in crowded housing. In fact, more than half (55 percent) of all workers living in overcrowded conditions earn $15 an hour or less even though these workers account for only 37 percent of the total workforce. In short, overcrowding is primarily, but by no means exclusively, a problem associated with low-wage workers.

|

Overcrowding by Occupation

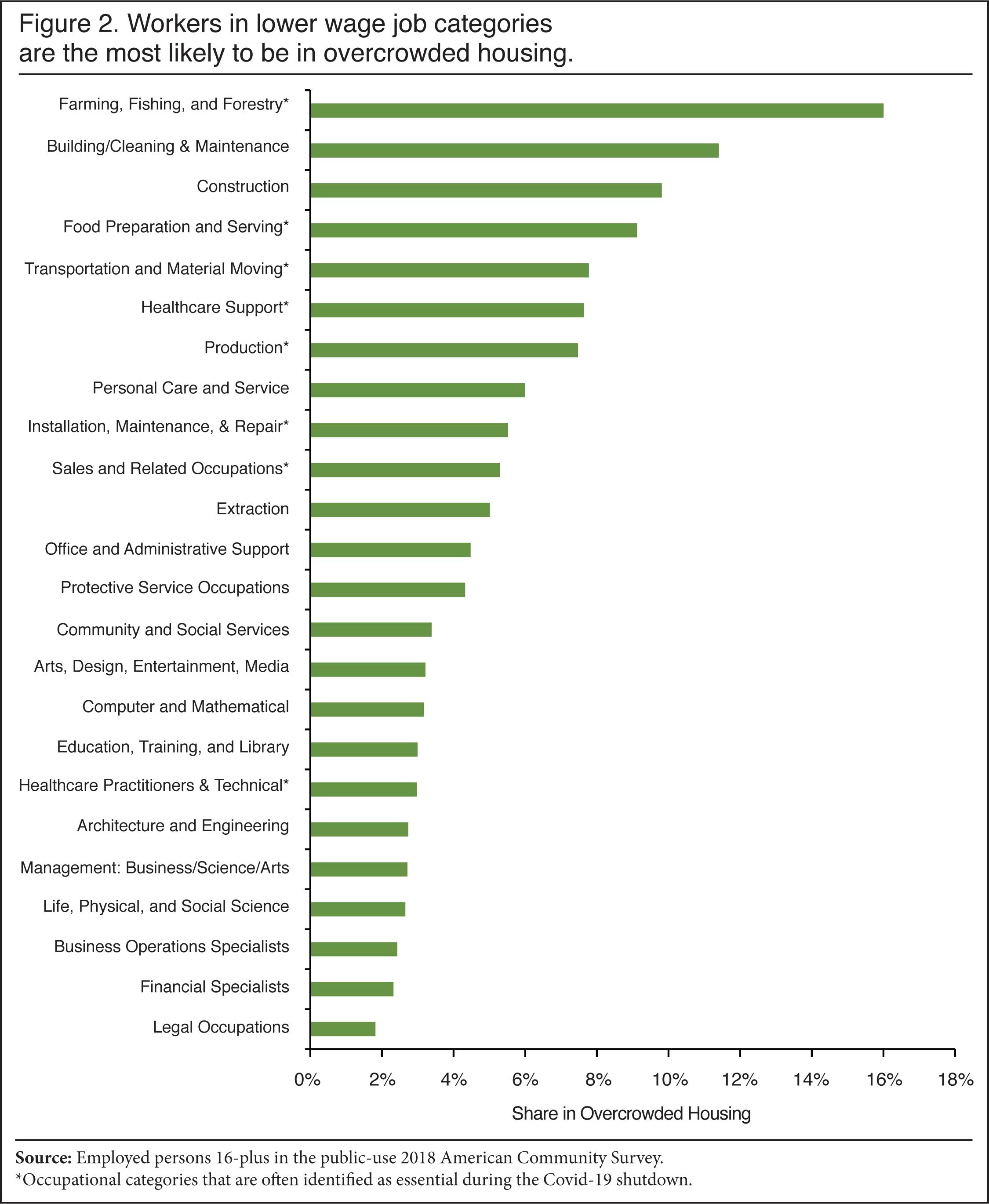

Figure 2 reports the share of workers (immigrant and native) in broad job categories who live in overcrowded housing. These broad occupational categories are defined by the Department of Commerce and coded into the American Community Survey (ACS).10 A broad category is one such as “production workers”, which includes all those who make or manufacture things. An example of a specific occupation within that category would include only workers who are involved in processing meats. Later in this report, we provide figures for specific occupations. Figure 2 shows that workers employed in farming, fishing, and forestry; building cleaning and maintenance; construction; food preparation; transportation and moving; health care support; production; personal care and service; installation, maintenance and repair; and sales and related jobs are among the most likely to live in crowded housing. Many of these job categories are low-wage and are also thought to be essential during the Covid-19 pandemic. In the eight essential job categories combined identified in the figures, 16.5 percent of immigrant workers live in crowded housing compared to 4.4 percent of native-born workers. Taken together, immigrants comprise 18.3 percent of all workers in these jobs, but 45.9 percent of those in crowded conditions.

|

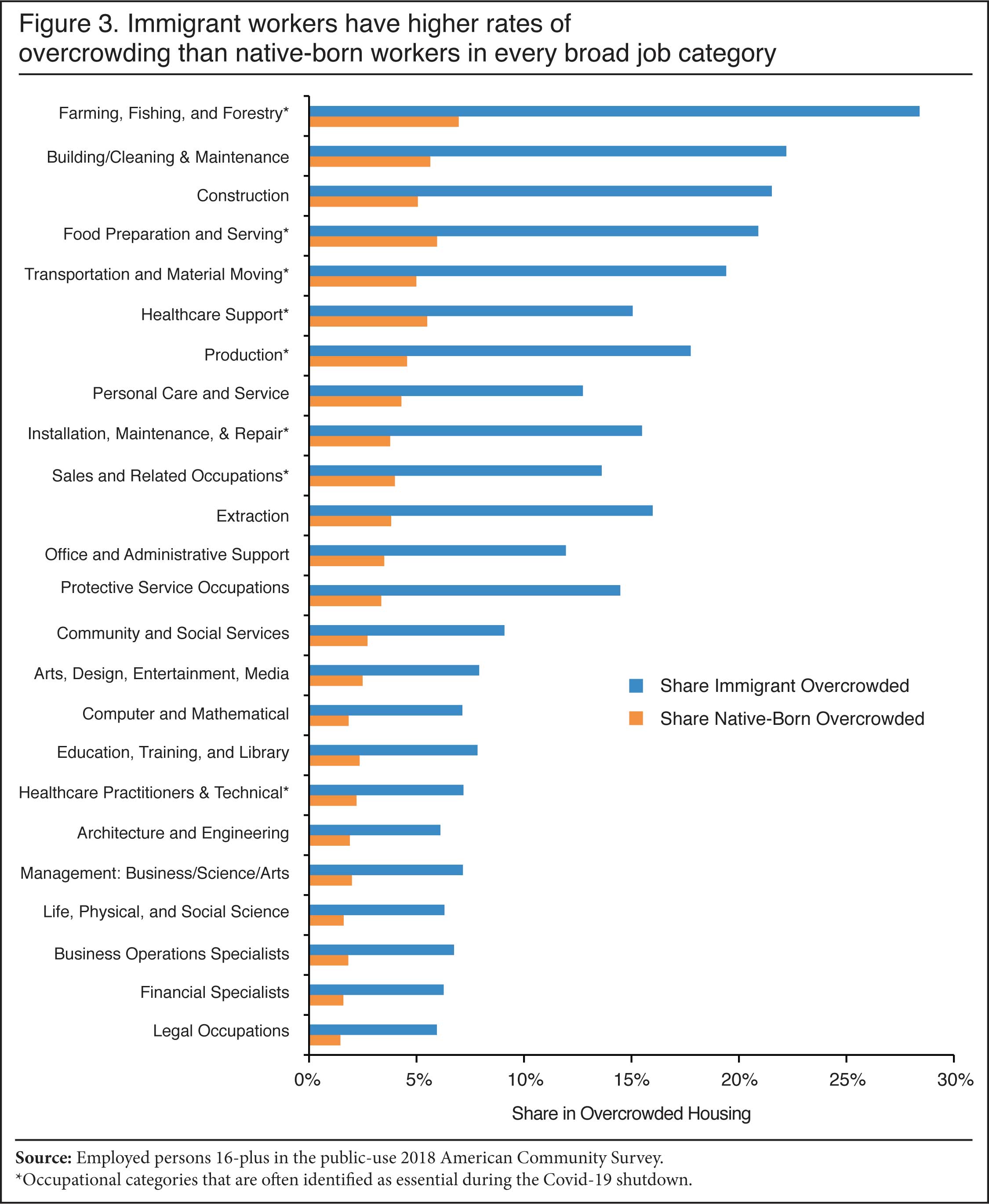

Figure 3 reports the share of immigrant and native-born workers living in overcrowded conditions in these same broad job categories. Foreign-born workers are much more likely to live in crowded homes than natives in every type of job. Figure 4 shows the same pattern holds in specific occupations within the broad categories thought to be essential, with immigrants being much more likely to live in a crowded home than natives who work at the same occupation.11 Some of the occupations are critical to the nation’s production, transportation, and sale of food.

|

|

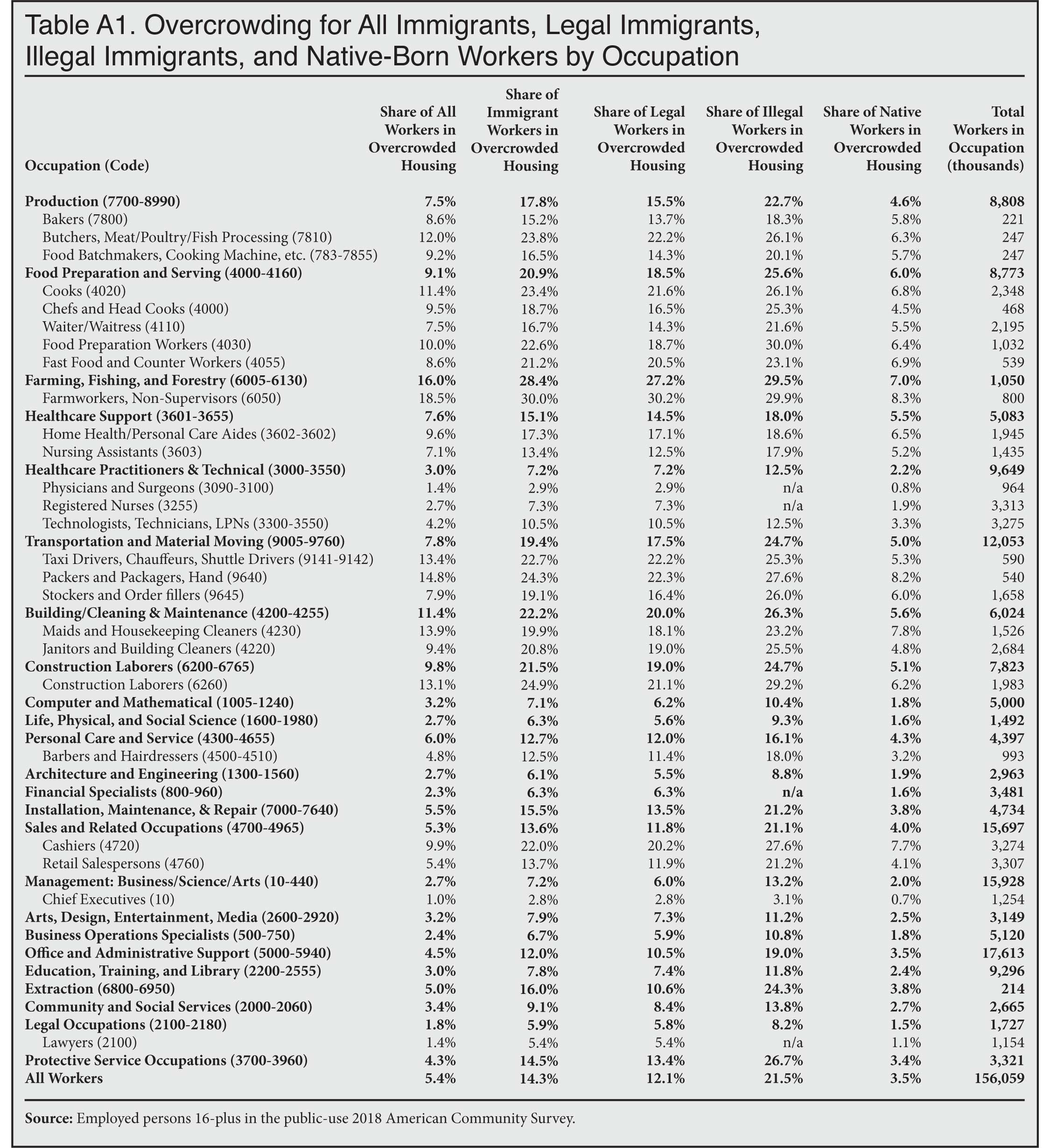

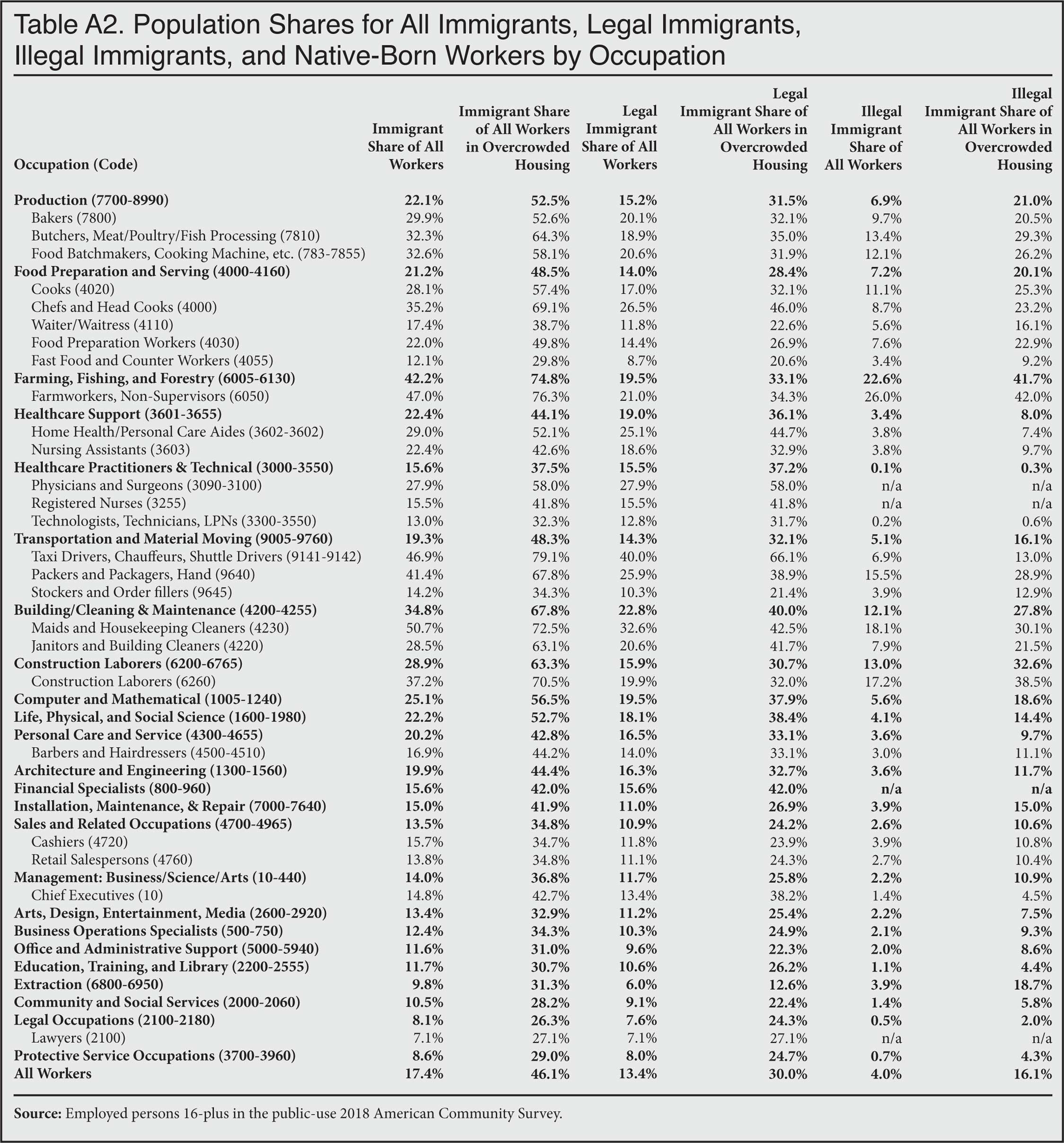

Immigrants comprise a very large share of workers in crowded housing in all of the specific occupations shown in Figure 5. Perhaps surprisingly for some, the upper smaller bar in Figure 5 shows that immigrants are not the majority of workers in any of these occupations. Most workers in every one of these occupations are native-born. Despite not being a majority of all workers in any of the 14 specific occupations reported in the figure, immigrants are the majority of workers living in overcrowded conditions in eight of the occupations. In four of the specific occupations (butchers and other meat processors, packers and package handlers, chefs and head cooks, and farmworkers), immigrants account for nearly two-thirds or more of those whose homes are overcrowded. (Tables A1 and A2 in the appendix of this report show more detailed overcrowding statistics for specific occupations as well as broad occupational categories.) Any understanding of overcrowding in these occupations has to appreciate the important role immigration plays in dramatically increasing the number of overcrowded workers in some sectors of the economy.

|

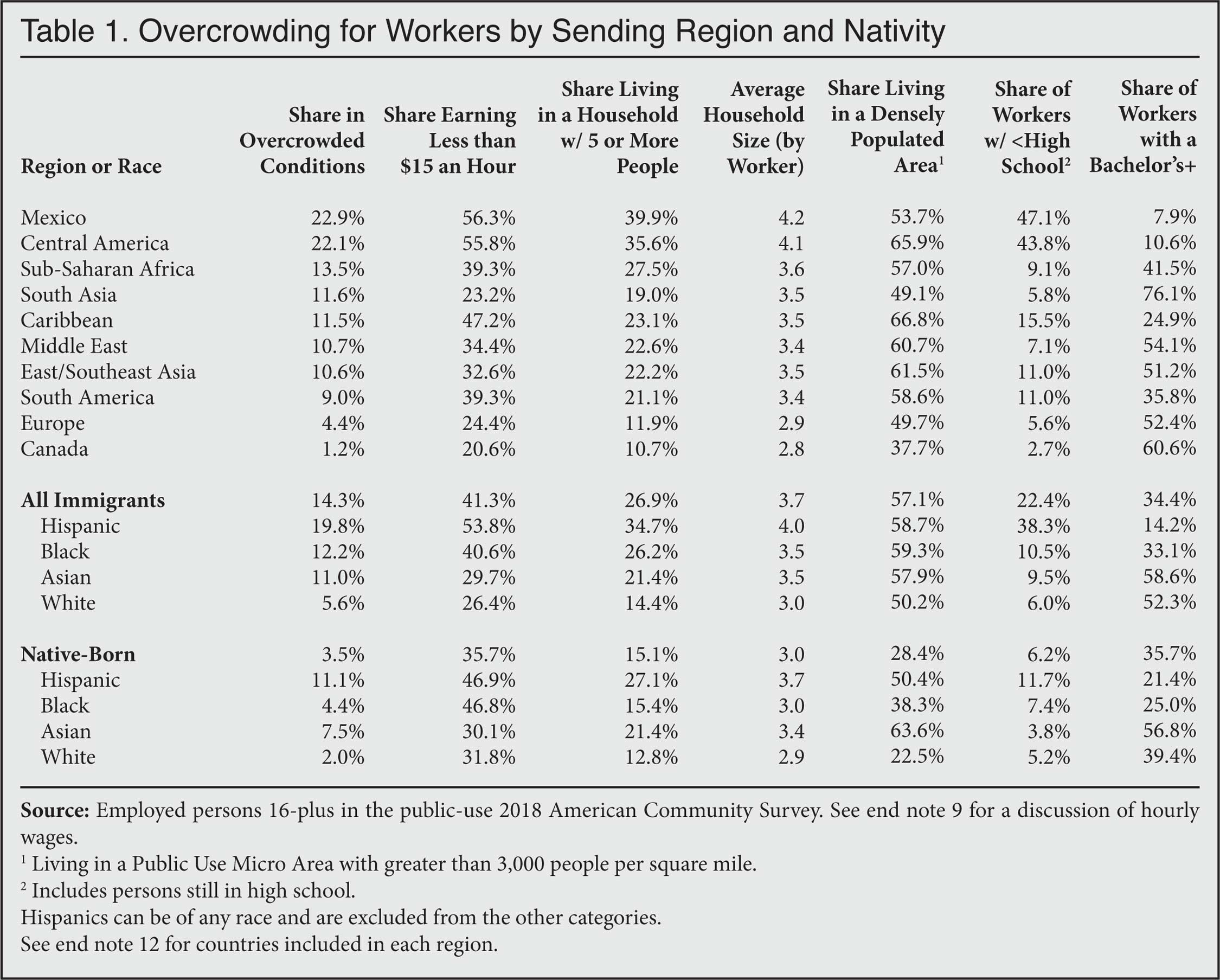

Sending Regions

Table 1 shows overcrowding for workers by sending region, with Canada and Mexico shown separately.12 The table indicates that overcrowding is higher among immigrant workers from most of the major sending regions compared to native-born workers. Not surprisingly, Table 1 shows that immigrants from sending regions earning lower wages tend to have higher rates of overcrowding. Also not surprising is that those immigrant groups that have lower levels of education also tend to earn modest wages. In addition to wages and education, Table 1 indicates that workers from regions that have larger household sizes and are concentrated in more densely populated areas are also more likely to live in overcrowded housing. As we will see, these factors are often linked to crowding as well.

|

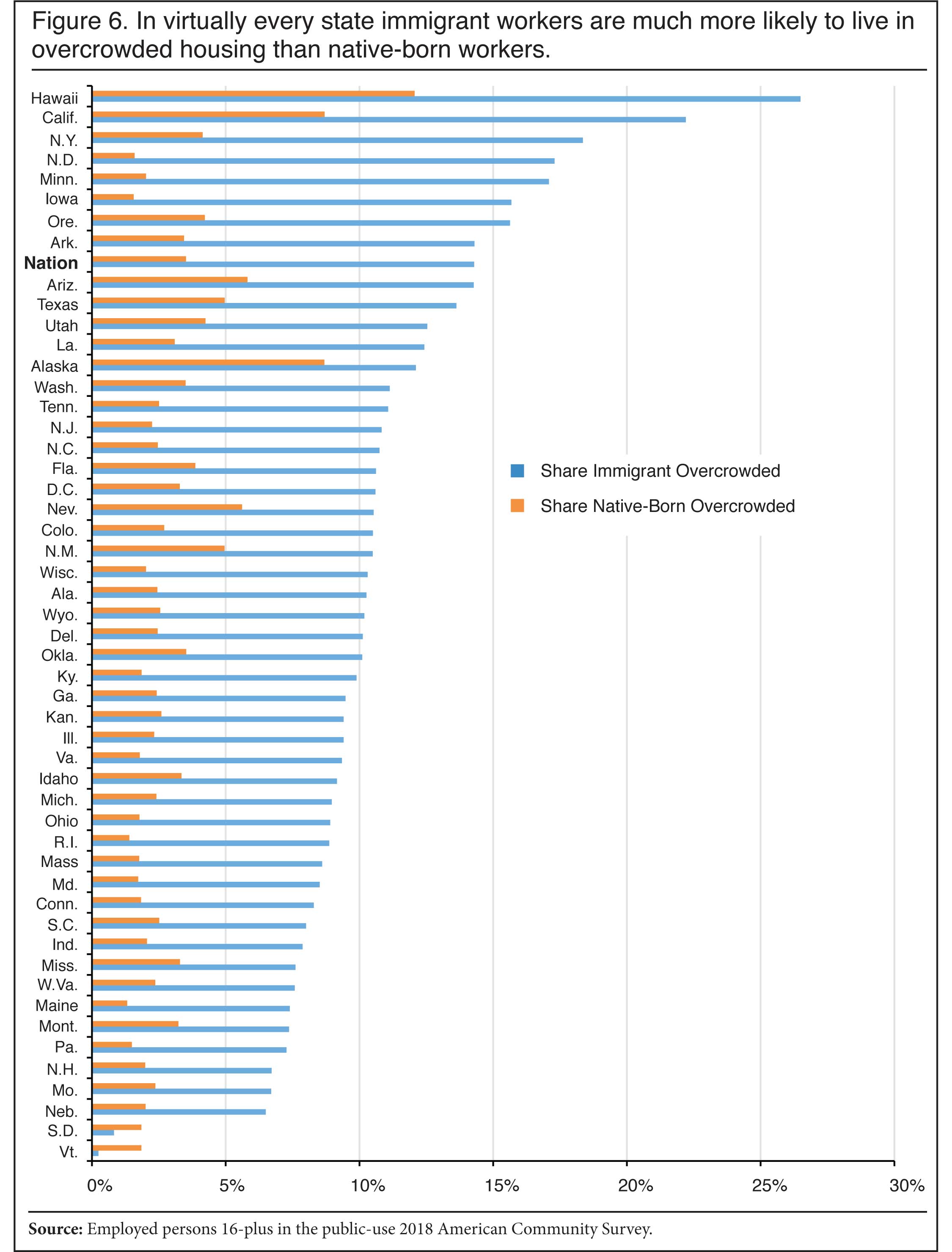

States, Cities, and Counties

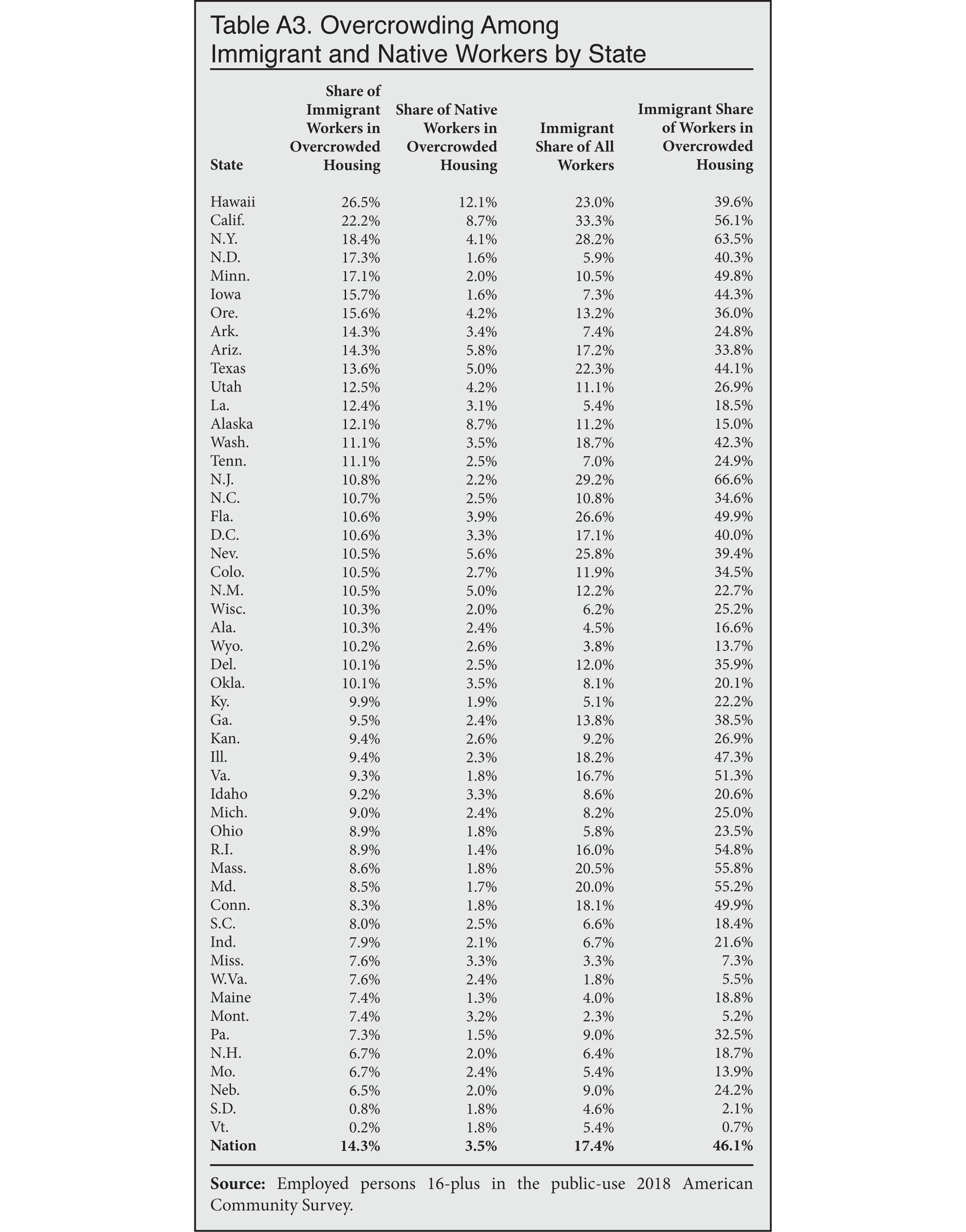

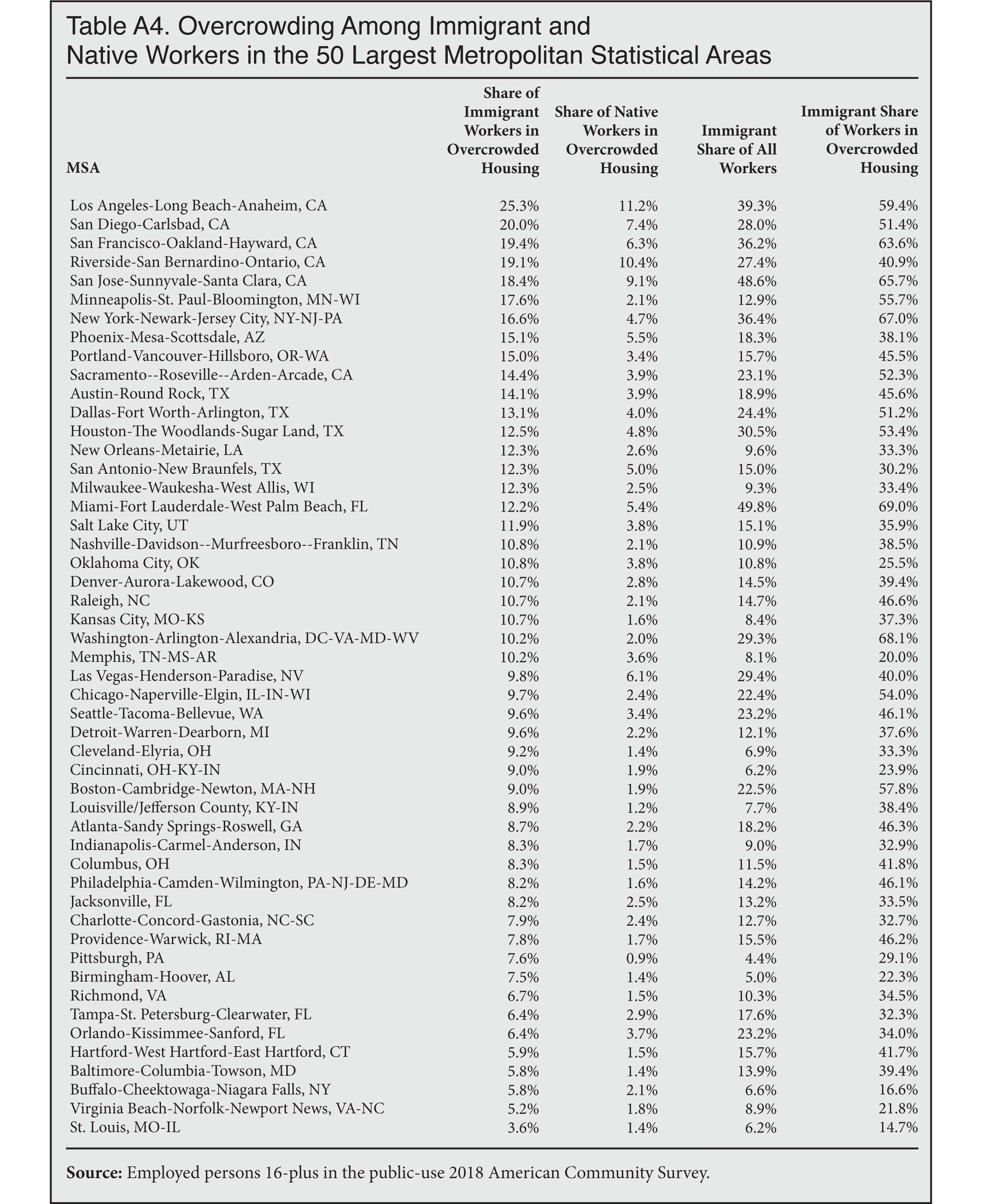

In Figure 6, we see that overcrowding is much more common among immigrants workers than native-born workers in just about every state in the country. Table A3 in the appendix reports additional information by state. (Appendix Table A4 provides information for the 50 largest metropolitan areas.) Nationally, the 14.3 percent of immigrant workers living in overcrowded housing is four times that of the 3.5 percent of native-born workers. In 46 states and the District of Columbia, crowding among immigrant workers is at least twice that of natives. In 22 states, the rate for immigrant workers is at least four times as high as that of native workers. As a result, immigrants comprise a very large share of workers living in crowded conditions in many states. Table A3 indicates that in 10 states immigrant workers accounted for about half or more of those in overcrowded households and in 14 additional states they account for one-third or more. Nationally, they account for 46.1 percent of all workers living in crowded conditions, compared to their 17.4 percent share of all workers.

|

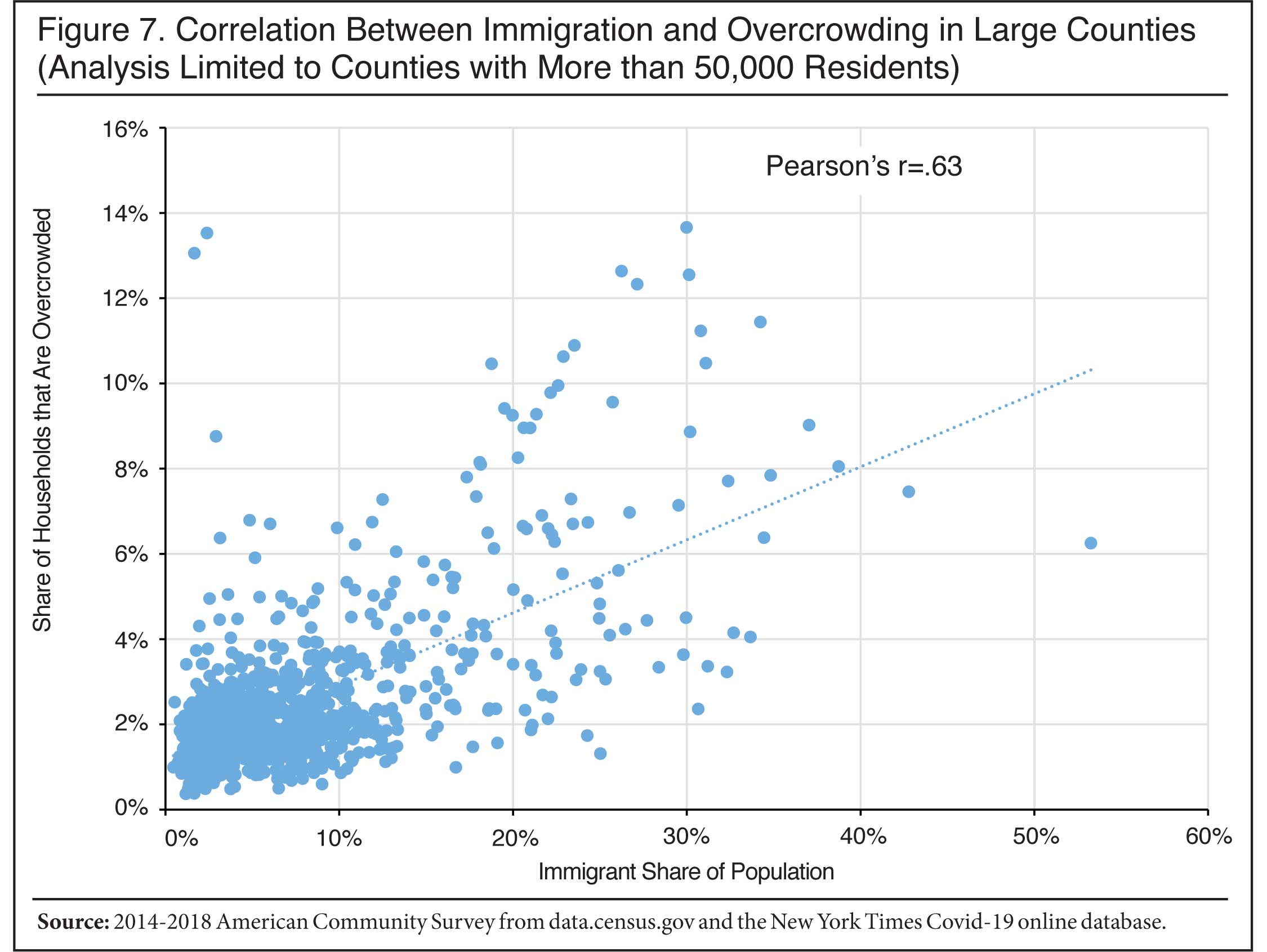

The impact of immigration on overcrowding can also be seen at the county level. A comparison across the nation’s largest counties shows a correlation of .63 between the immigrant share of the population and the share of households that are overcrowded.13 The scatterplot shown in Figure 7 illustrates the relationship. The square of a correlation, in this case .40, can be interpreted as indicating that the presence of immigrants explains 40 percent of the variation in overcrowding across counties. However, a correlation only reports the relationship between two variables, and should always be interpreted with caution. Factors other than immigration impact the incidence of overcrowding. Once more data becomes available and the disease has run its course, researchers will be better able to determine the complex relationship between all the variables that contributed to the spread of Covid-19. However, it seems certain that overcrowding is one of the factors facilitating the spread of the disease, just as it does other similar infections. It is worth adding that the correlation in larger counties between the immigrant share of the population and per capita positive Covid-19 test results is .36. It is likely that one of the reasons for this relatively strong correlation is the large impact immigration has on overcrowding.14

|

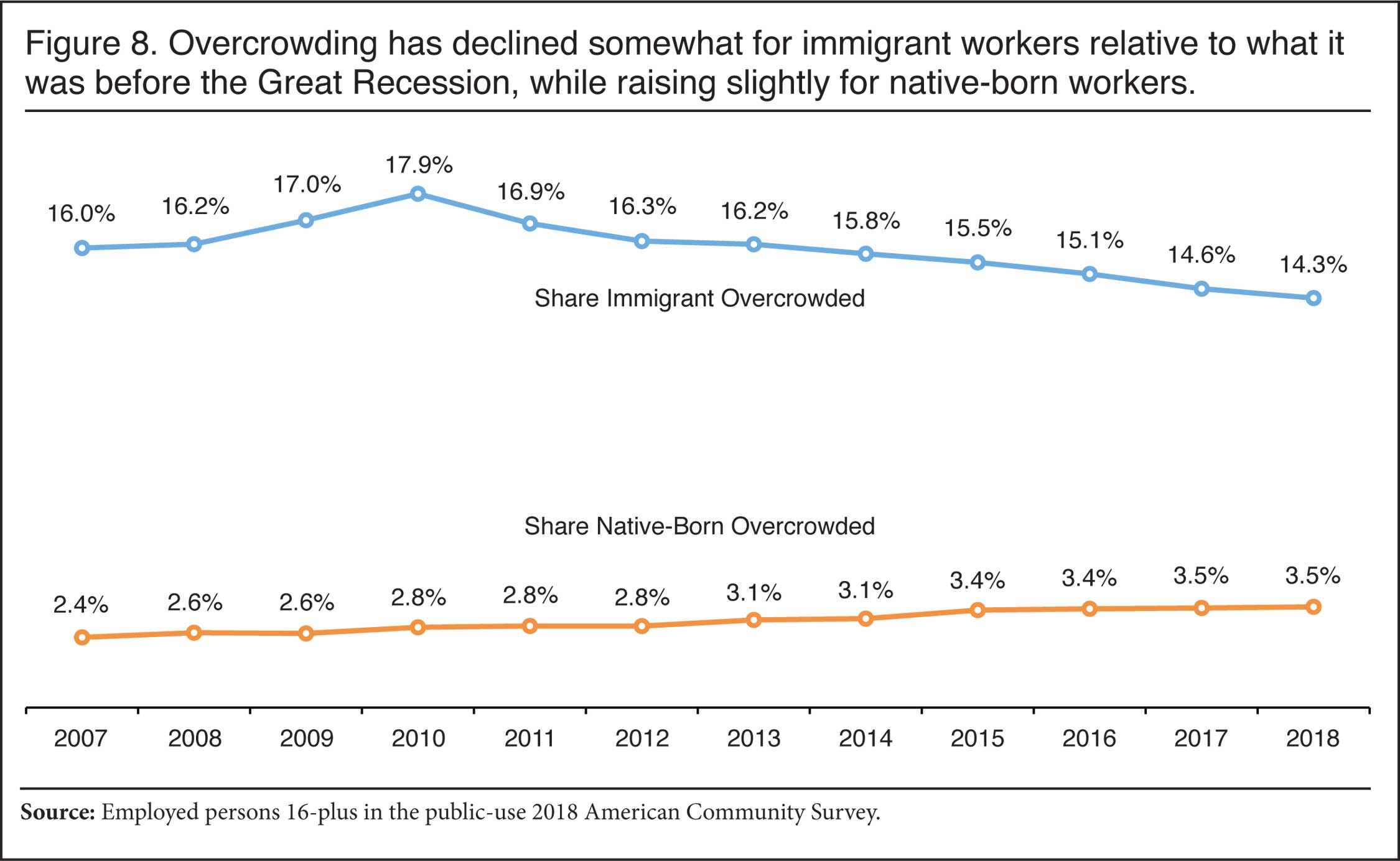

Overcrowding Over Time

The share of immigrant workers in overcrowded housing has been relatively stable, though it has declined somewhat in recent years. Figure 8 shows that before the Great Recession in 2007, 16 percent of immigrant workers lived in overcrowded housing compared to 14.3 percent in 2018. Overcrowding among native-born workers has increased slightly, by 1.1 percentage points, so the difference between the two groups has narrowed some. One reason for the modest decline in the overall share of immigrant workers living in crowded conditions is that the share who are recently arrived in the United States has declined. In 2007, 32 percent of immigrant workers had lived in the country for less than 10 years, whereas in 2018 it was 22 percent. Since overcrowding tends to be more pronounced among new arrivals, this decline lowers the fraction of all immigrant workers who are in crowded conditions. However, it is worth adding that overcrowding is not simply a problem among new arrivals. Of immigrant workers who had lived in the country for 10 or more years, 13.4 percent lived in overcrowded housing in 2018.

|

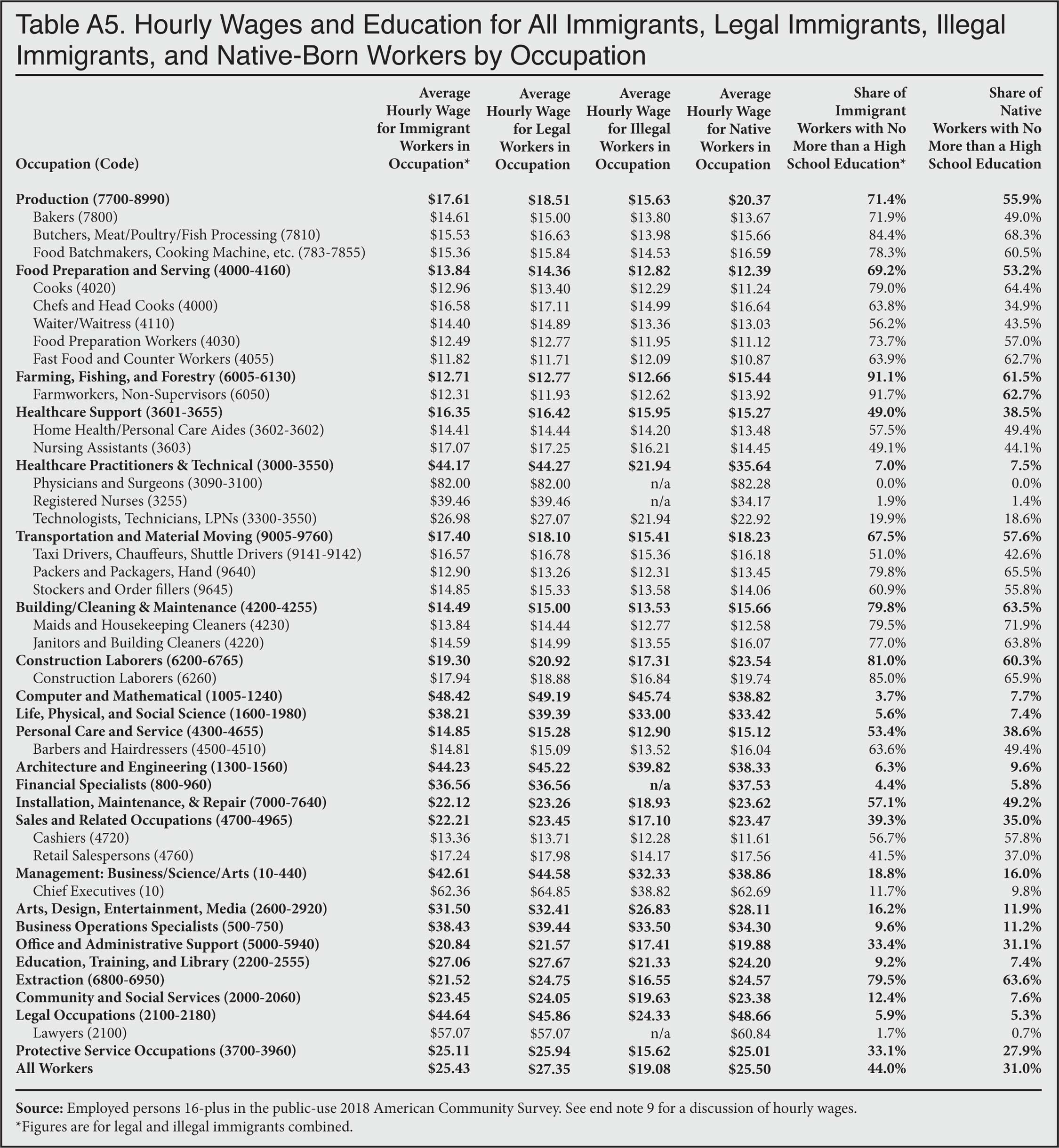

Wages by Occupation

One might assume foreign-born workers earn much less than natives in the same occupations, and this explains why they are much more likely to live in overcrowded conditions. However, this is not a very plausible explanation when looking at specific occupations. Table A5 in the Appendix shows the average hourly wage of immigrants and natives in each occupation shown in Figures 4 and 5, as well as some other specific occupations. In general, the differences in hourly wages are not that large, averaging only about 4 percent in the 14 specific occupations reported in Figures 4 and 5.15 It should be noted that many things can impact average wages for immigrants and natives, such as education level, gender, age, and the local cost of living. However much these things may matter, Table A5 indicates that immigrants and natives who work in the same specific occupation generally earn similar wages. This should not be too surprising since the table shows that the education levels of immigrants and natives are similar in the same occupation. Moreover, since they are doing the same work, we would expect both groups to earn roughly the same wage. Despite similar wages, however, immigrant workers are much more likely to live in crowded conditions in the same occupation.

In eight of the 14 specific occupations shown in Figures 4 and 5, Table A5 indicates immigrant workers actually earn more than natives, though typically not much more. For example, foreign-born cooks earn about 15 percent more than native-born cooks, which is one of the larger differences in hourly wages in these 14 occupations. But immigrant cooks are three times more likely to live in a crowded home than their native-born counterparts. Factors other than simply hourly wage must explain the large difference in rates of overcrowding between foreign-born and native-born workers within the same occupation.

We can also see this is clearly the case in Figure 9, which reports overcrowding by wage for all immigrants and natives. The figure shows that immigrant workers earning about the same wage as natives are still much more likely to live in overcrowded housing. This further demonstrates that wages alone do not explain the large difference in the share in overcrowded households between immigrants and natives. That said, it is also the case that workers earning higher wages are much less likely to live in overcrowded housing. This is especially true for immigrant workers. With higher incomes, overcrowding declines more steeply for the foreign-born than for native-born workers. This is an important fact that indicates that if lower-wage jobs paid more, then it is likely that overcrowding would be less pronounced, particularly among immigrants.

|

Household Size

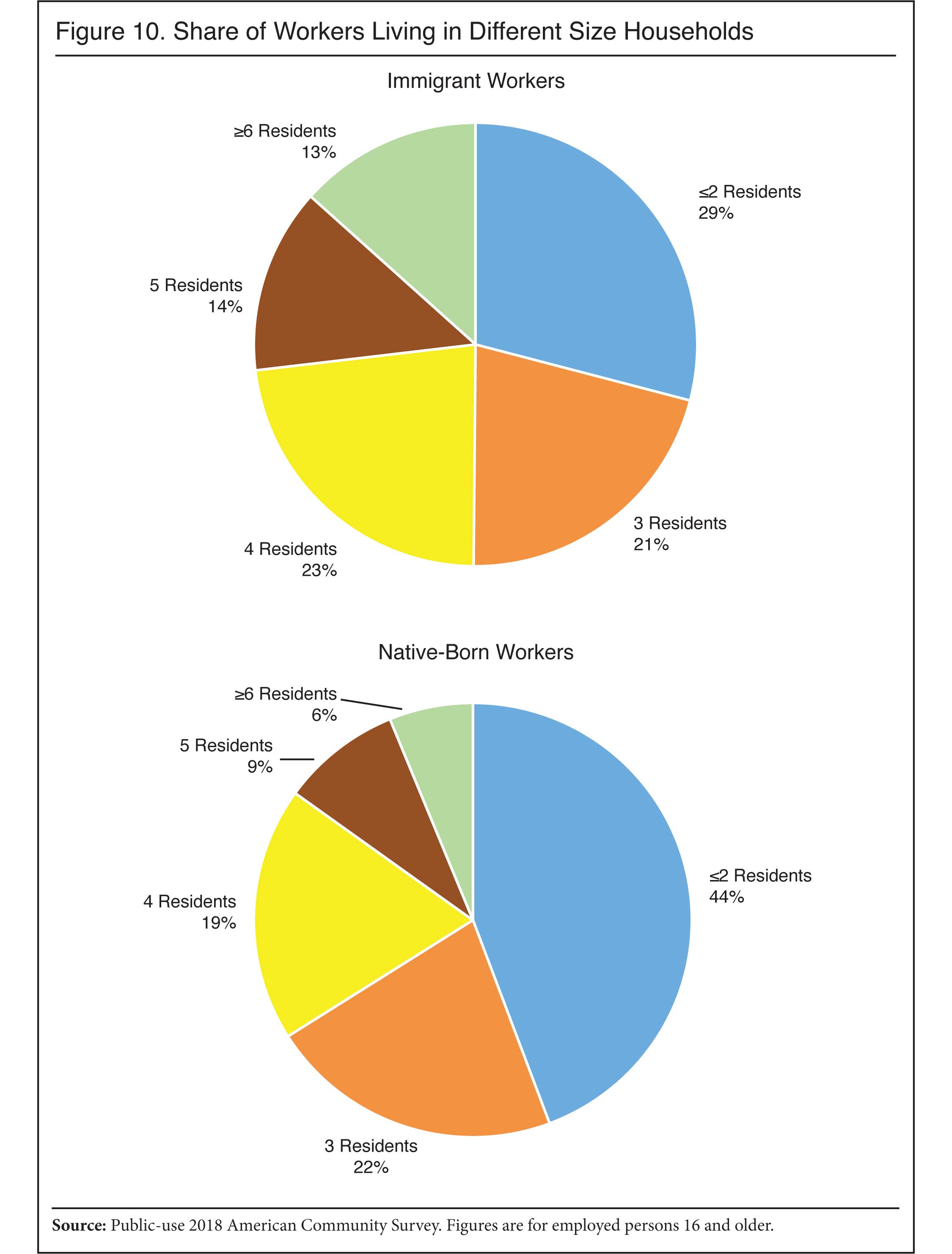

Figure 10 reports the share of immigrant and native workers living in different size households. Immigrants are much more likely to live in larger households — 27 percent of immigrant workers live in a household of five or more compared to 15 percent of natives. This is important because workers, immigrant or native, living in larger households are much more likely to reside in overcrowded conditions. In 2018, 24 percent of workers (immigrant and native) lived in households with five or more members and were overcrowded. In contrast, only about 1 percent of workers in households with three or fewer members were overcrowded.

|

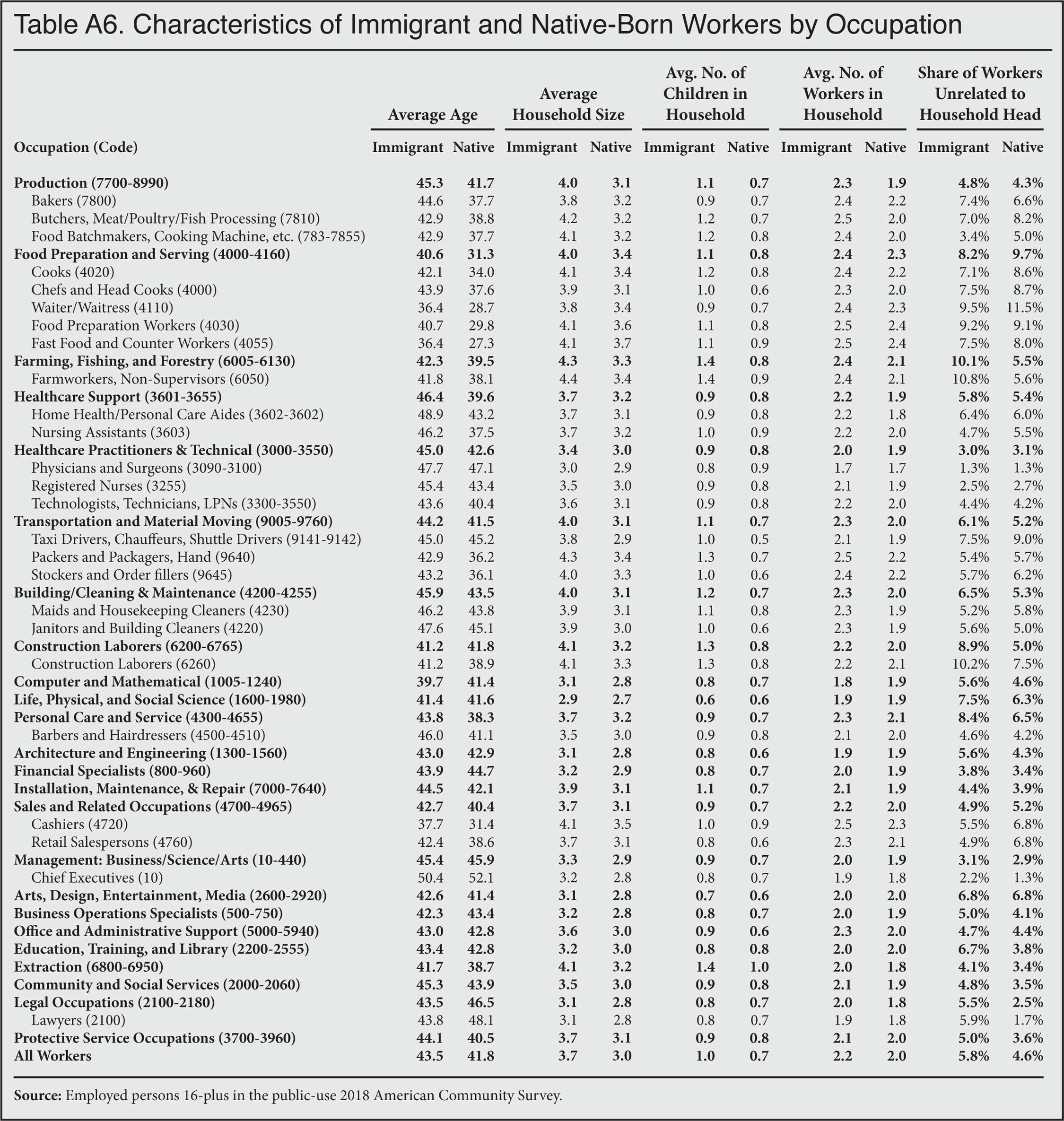

Appendix Table A6 reports more detailed information about the kinds of households in which immigrant and native workers live. On average, Table A6 shows that workers in immigrant households live with one child, while the average native-born worker lives in a household with .7 children. This is a significant difference. Table A6 shows that immigrant workers also live with more adults on average. The presence of more children and more adults explains why immigrant worker households are larger. Of course, more adults can mean more workers and income, and Table A6 does show that on average immigrant workers live in households with more workers. But despite the potential for more income, foreign-born workers are still more likely to live in a crowded household.

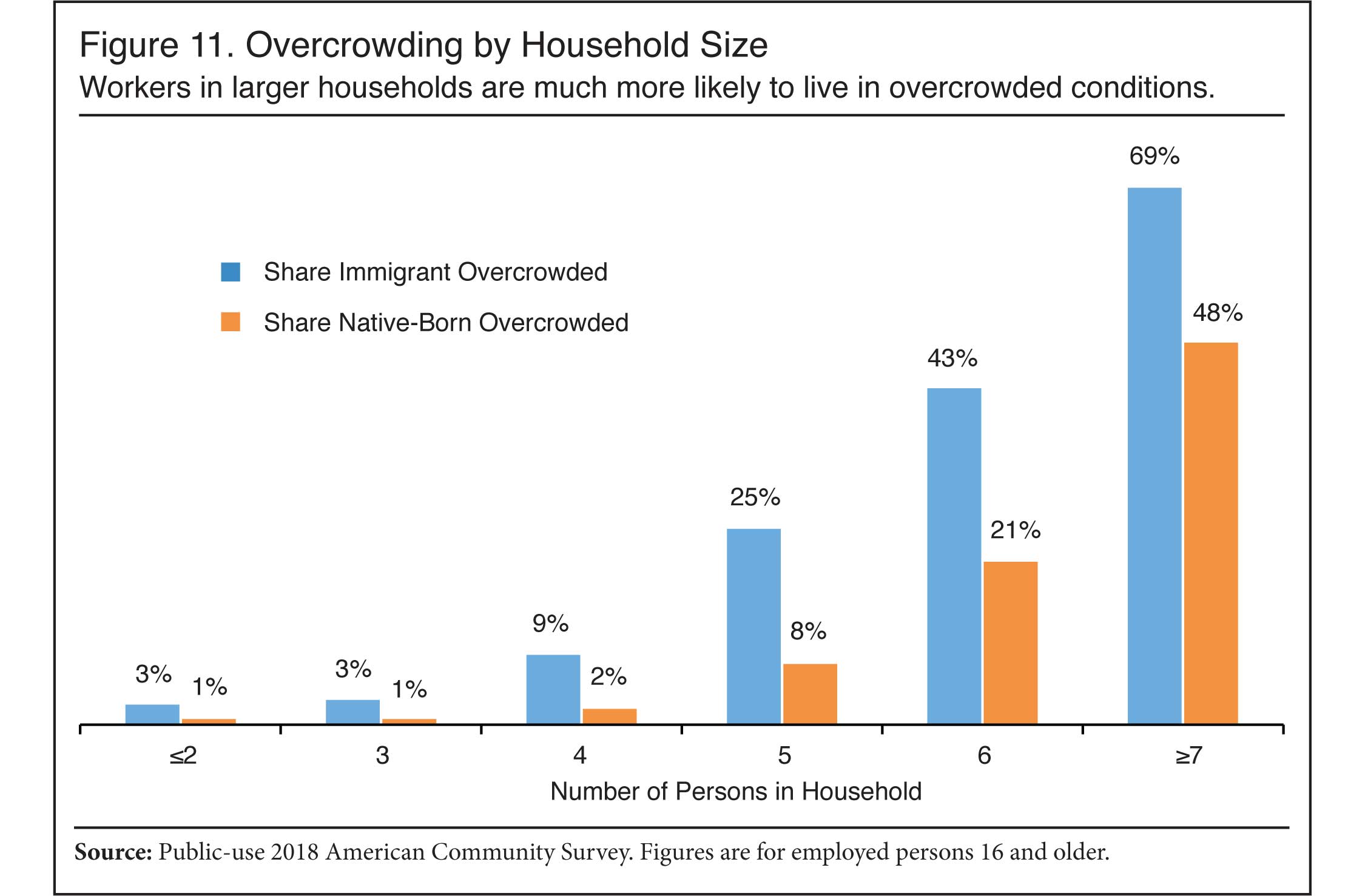

Figure 11 shows the share of immigrant and native workers living in crowded households based on the number of people living with them. The figure indicates that foreign-born workers are still much more likely to live in overcrowded housing even when there is the same number of people in the household. For example, 25 percent of immigrant workers living in five-person households are in overcrowded homes, compared to 8 percent of native-born workers living in the same size household. As is the case with wages, differences in household sizes do not by themselves entirely explain the difference between immigrant and native overcrowding.

|

Urban Areas

Cities tend to have higher housing costs and, as a result, overcrowding tends to be higher in urban areas. While not the best data for exploring this question, the ACS does include a variable that identifies those who live in the central city of Metropolitan Statistical Areas (MSA), but unfortunately, 47 percent of workers in the 2018 sample are coded as “indeterminable”.16 Still, we do find that 10 percent of workers residing in a central city live in overcrowded housing compared to 5 percent who live outside of a central city. For those who report a value for the central city variable, 39 percent of immigrant workers live in a central city compared to 23 percent of the native-born. In 2018, 93 percent of immigrant workers lived in an MSA, compared to 78 percent of natives. However, MSAs include outlying areas that can be quite rural, so simply living in an MSA does not mean a person lives in an urbanized or even suburban area.

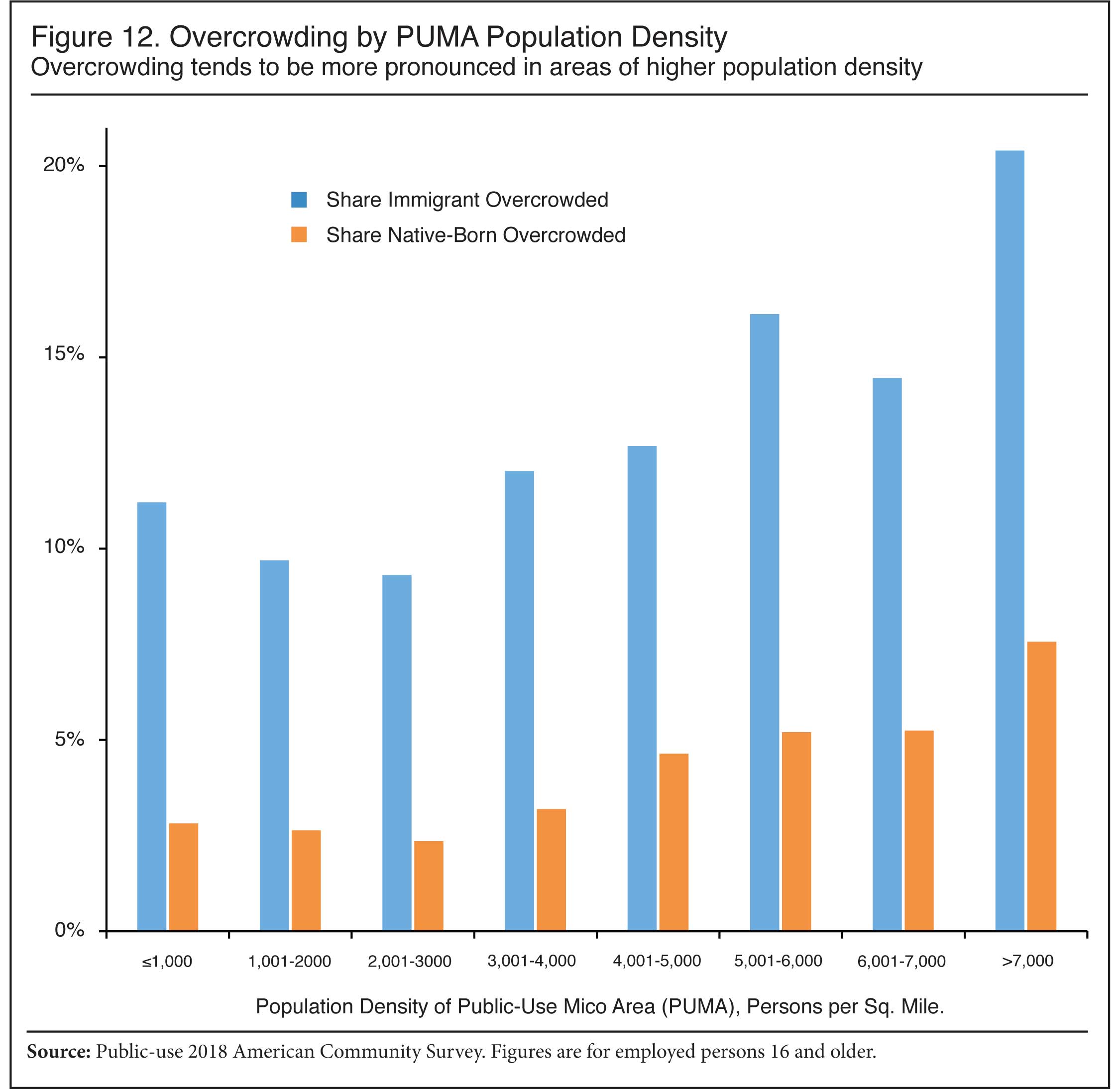

The public-use ACS data does include the population density of the Public Use Micro Area (PUMA) for every respondent. PUMAs vary a lot in land area but have at least 100,000 inhabitants. On average, foreign-born workers live in a PUMA with a population density of 8,805 people per square mile compared to 3,694 for the average native-born worker.17 There is no question that foreign-born workers are more likely to live in densely settled areas than are the native-born. Figure 12 shows the share of immigrant and native-born workers who live in crowded housing based on the population density of their PUMA. In general, areas of greater population density tend to have more overcrowding. Also, Figure 12 indicates that even when they live in areas of similar population density, immigrant workers are more likely to reside in overcrowded housing than are native-born workers.

|

It is worth noting that areas of less than 1,000 people per square mile actually have more overcrowding than more moderately dense areas with 1,000 to 3,000 people per square mile. This is because the least dense PUMAs include rural areas where farmworkers reside and where a good deal of meat and poultry processing takes place. As we have seen, these two types of workers have high rates of overcrowding. So while more densely populated areas with their higher cost of living do tend to have more overcrowding, there is significant overcrowding in some rural areas as well.

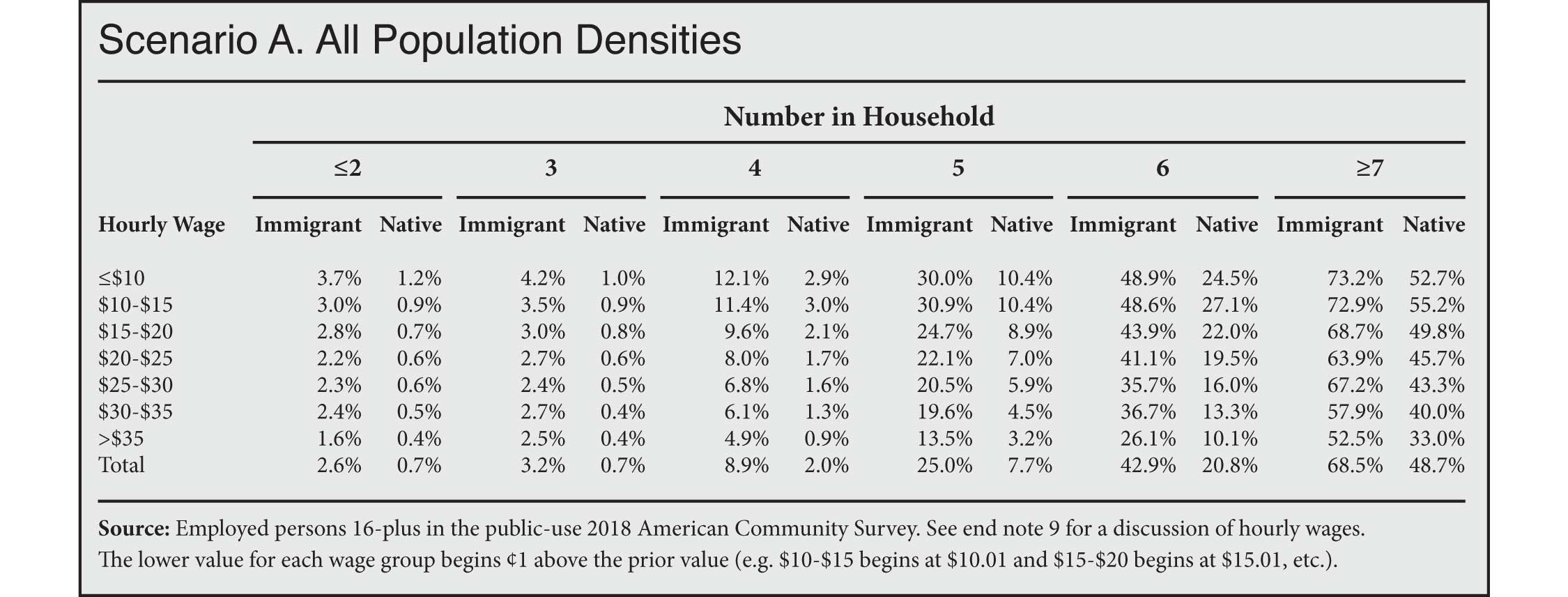

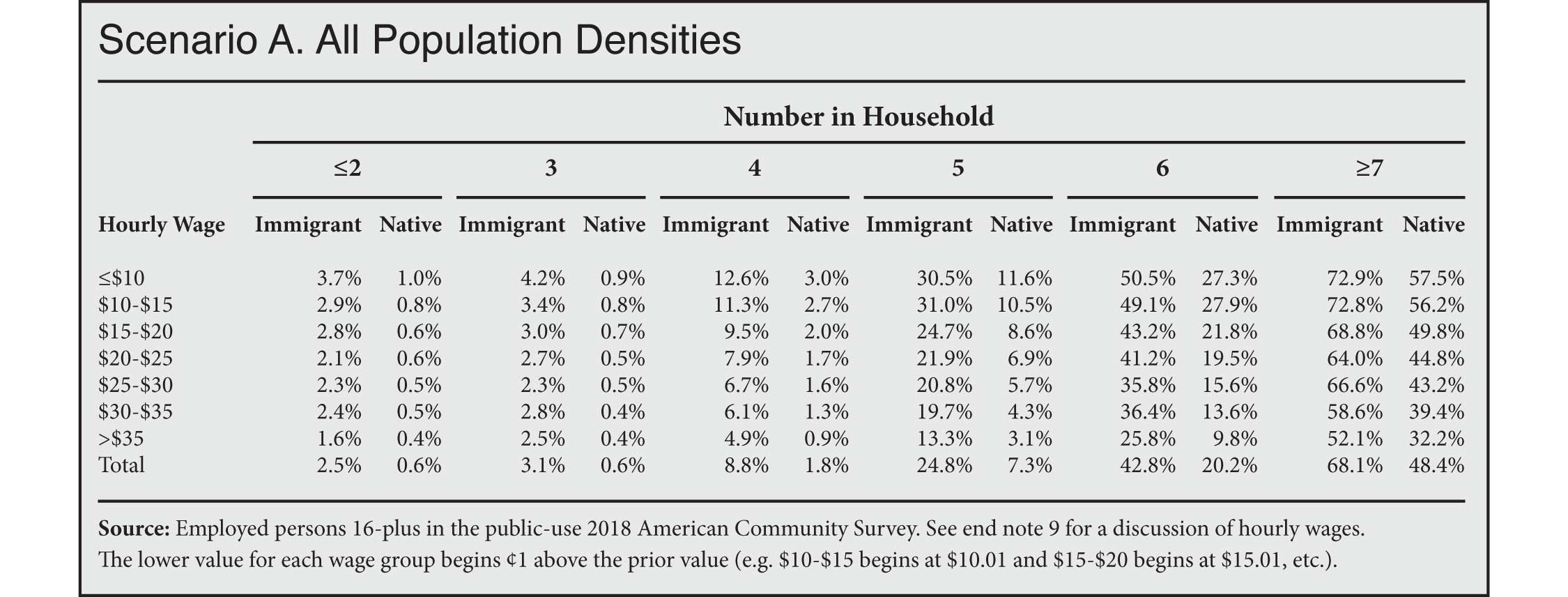

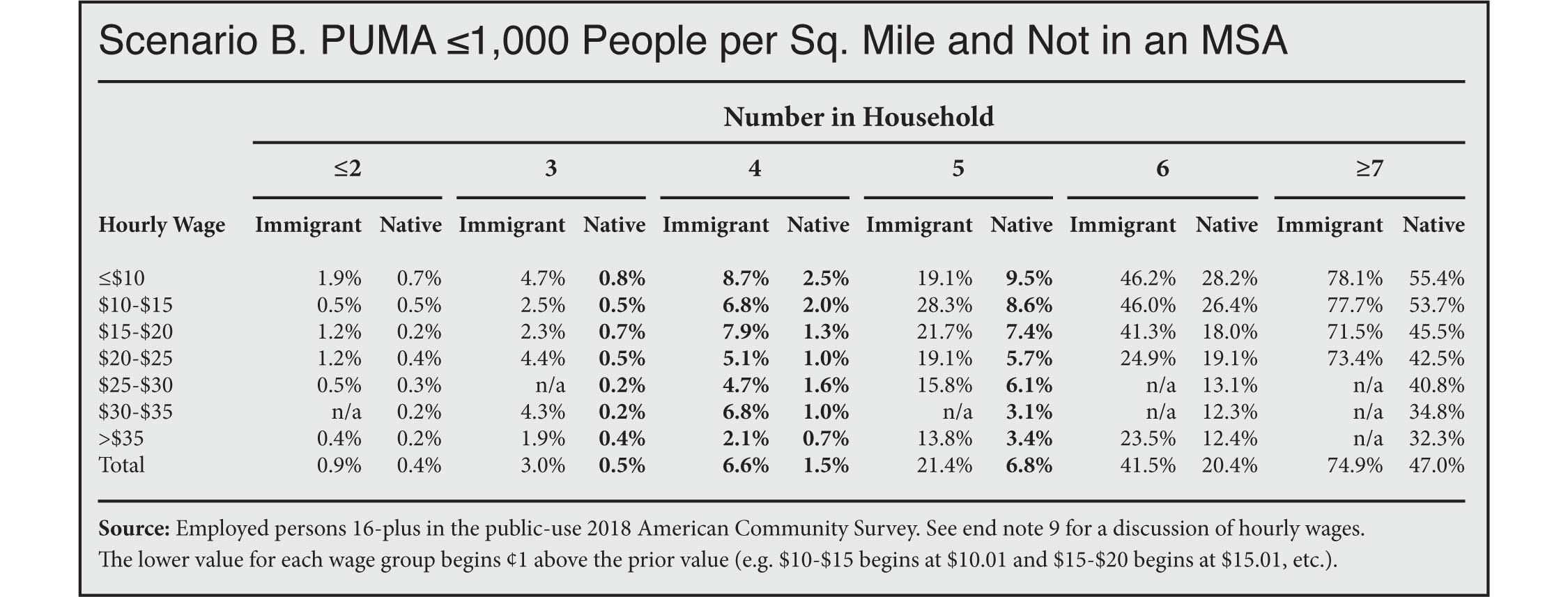

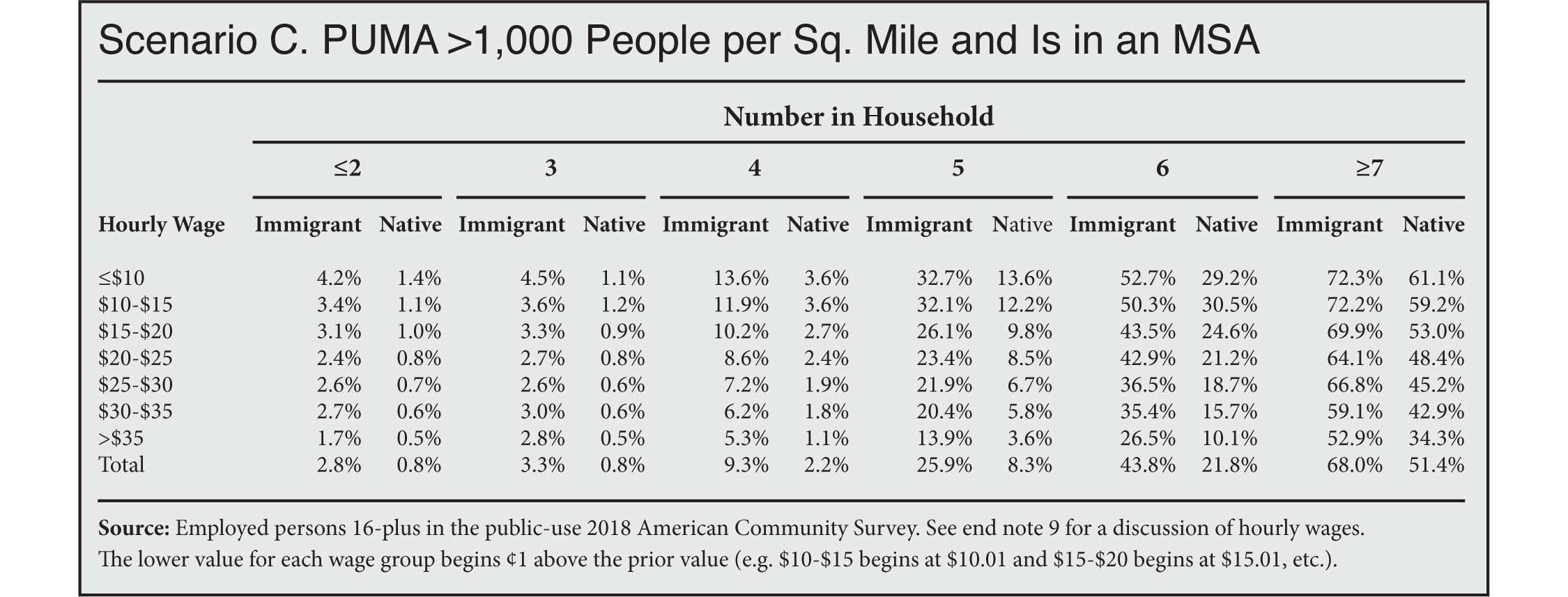

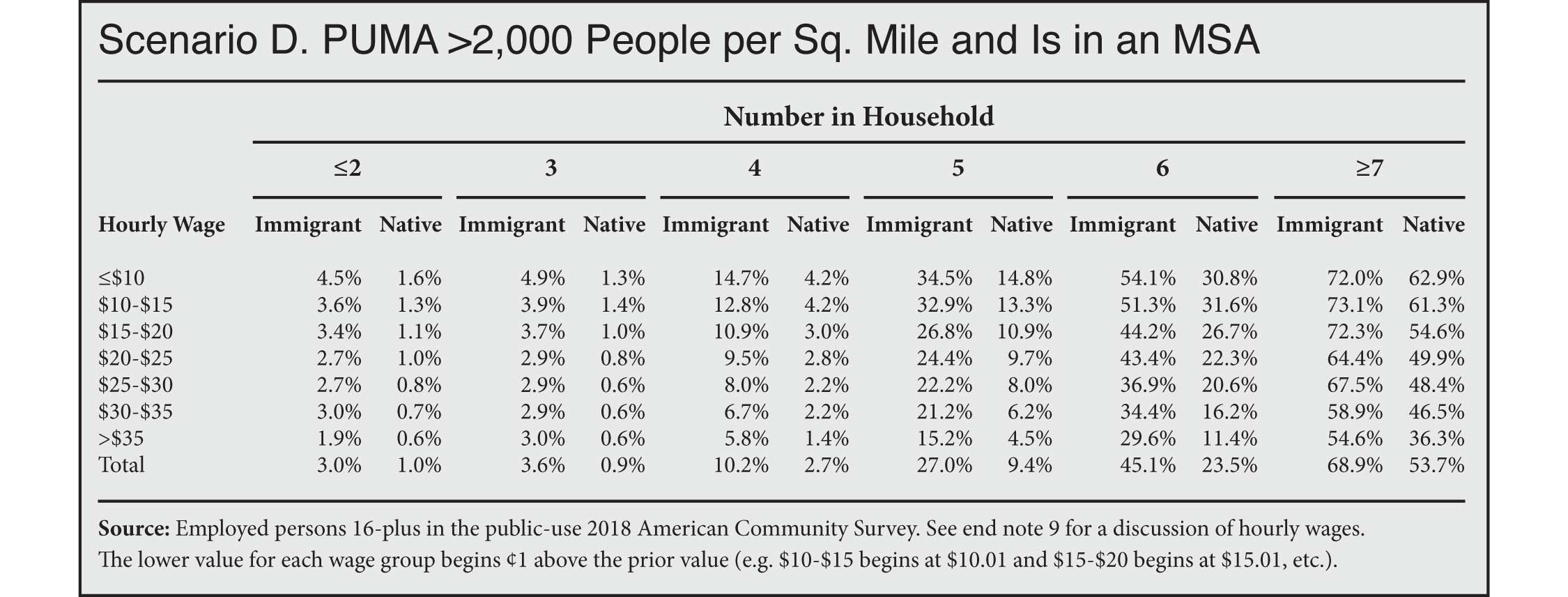

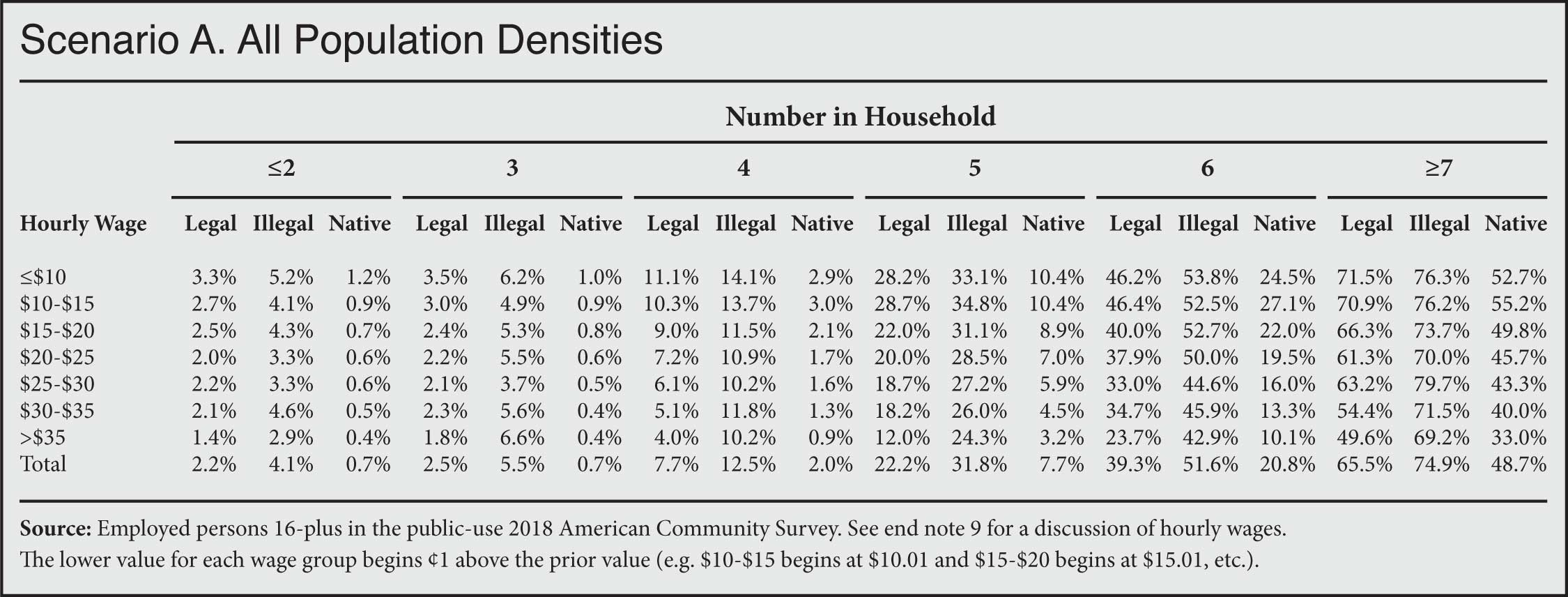

Wages, Household Size, and Density

Figure 13 examines overcrowding by several factors at once. The top part of the figure reports overcrowding for workers in households of three people. The figure further divides the data by wage and population density. For the purposes of the figure, high-density areas, which can be thought of as urban areas, are PUMAs with a population density of 3,000 or more people per square mile. Low-density areas are those with fewer than 1,000 people per square mile, which can be thought of as rural areas. The bottom of the figure shows the same information except for households with five members. As we have seen, overcrowding is relatively uncommon for workers who live in households with three or fewer members. That said, foreign-born workers in households with three members, earning similar wages to the native-born and living in areas of similar population density, are still quite a bit more likely to live in crowded housing. The bottom of Figure 13 shows that immigrant workers in five-person households are also much more likely than native workers to live in crowded housing, even when they earn similar wages, and live in areas of similar population density.

|

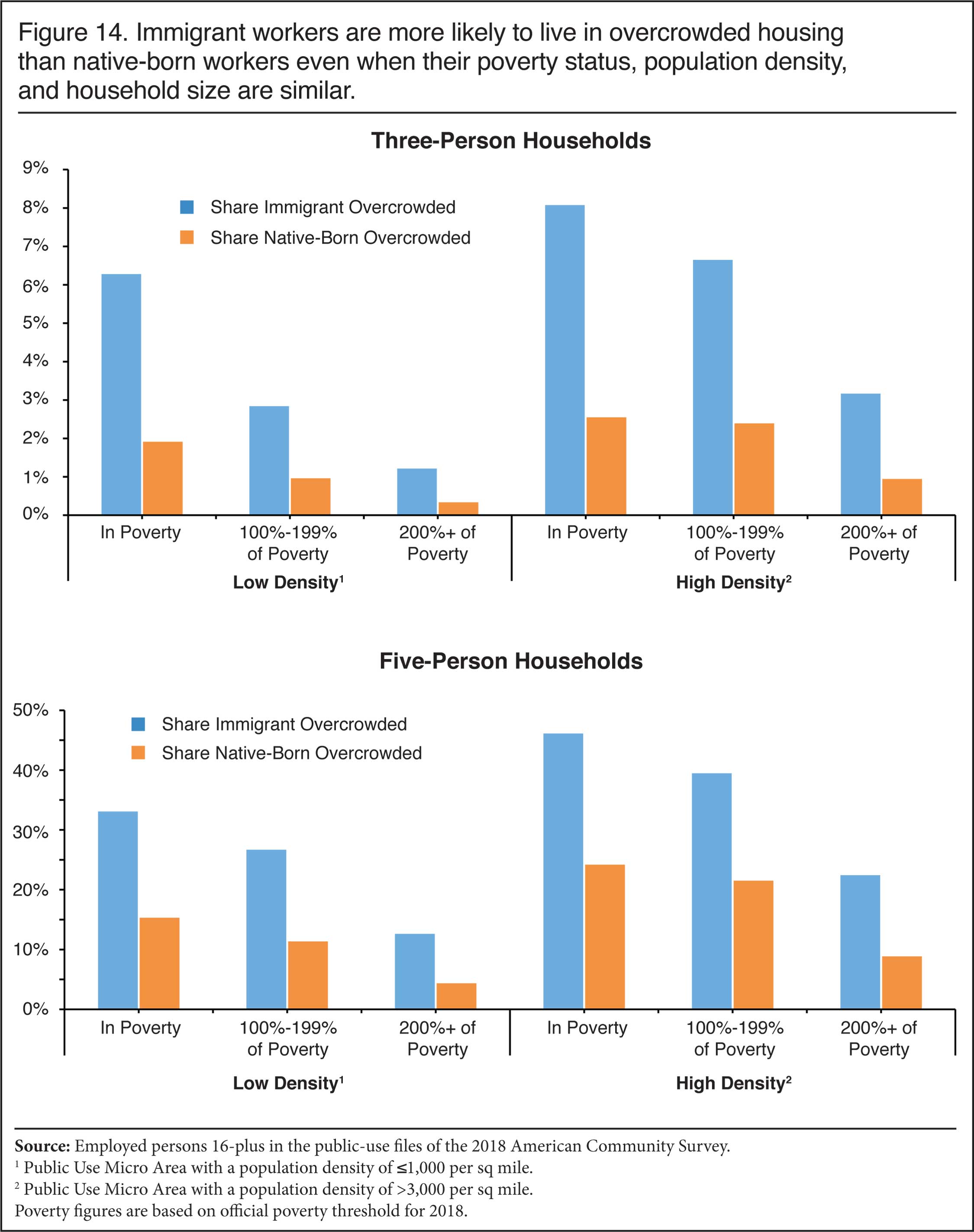

Poverty, rather than wages, is another measure of one’s economic situation. Poverty is based on a family’s total income from all sources, not just wages, and it reflects the number of people in the family.18 Immigrant workers are somewhat more likely to live in poverty than native-born workers — 8 percent vs. 5.5 percent. And this does contribute to the larger share in overcrowded housing. However, focusing only on those in poverty still shows immigrant workers are much more likely to live in crowded conditions. Of immigrant workers in poverty, 27.3 percent live in an overcrowded household compared to 9.1 percent of native-born workers in poverty. Immigrants also are more likely to live just above poverty, with an income between 100 percent and 199 percent of the poverty threshold. Of immigrant workers who can be thought of as living near the poverty line, 23.4 percent live in crowded homes compared to 8.1 percent of natives. Thus, immigrants’ higher rate of poverty or near-poverty cannot entirely explain their much higher rates of overcrowding.19 We can see this is the case even when household size and population density are included in the analysis.

Figure 14 is similar to Figure 13, except that, instead of wages, it reports overcrowding by poverty status along with household size and population density. Those with incomes 100 percent to 199 percent of the poverty threshold can be thought of as the near-poor. The figure shows that foreign-born workers in poverty or those with incomes that put them near the poverty line are much more likely to live in overcrowded households than their native-born counterparts, even when their household size is the same and they live in areas of similar population density. The same thing is also true for high-income immigrant workers. None of this should be surprising because, as we have seen, immigrant workers are much more likely to live in crowded households than are native workers, regardless of wages, household size, and population density. Figure 14 confirms the fact that immigrants’ hig rates of overcrowding are not simply because a larger share have low incomes. It is also worth adding that less than half of all workers in crowded homes, immigrant or native, are in or near poverty.20

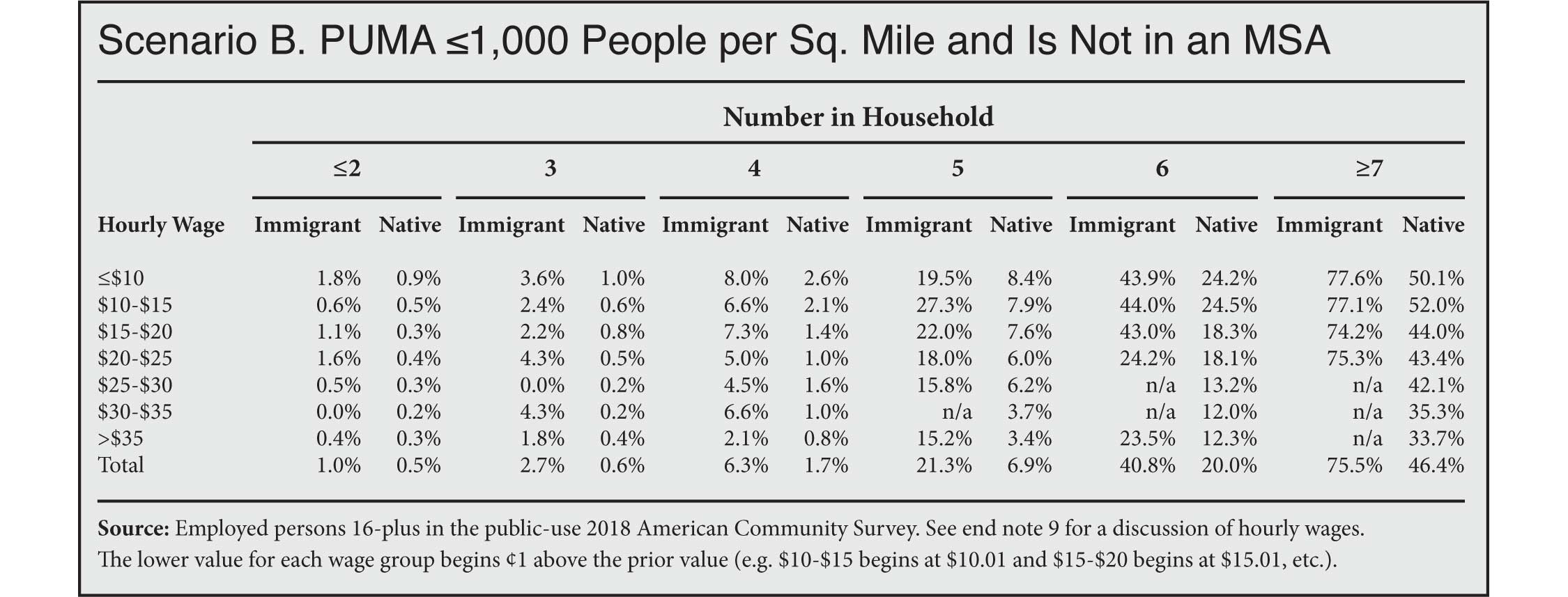

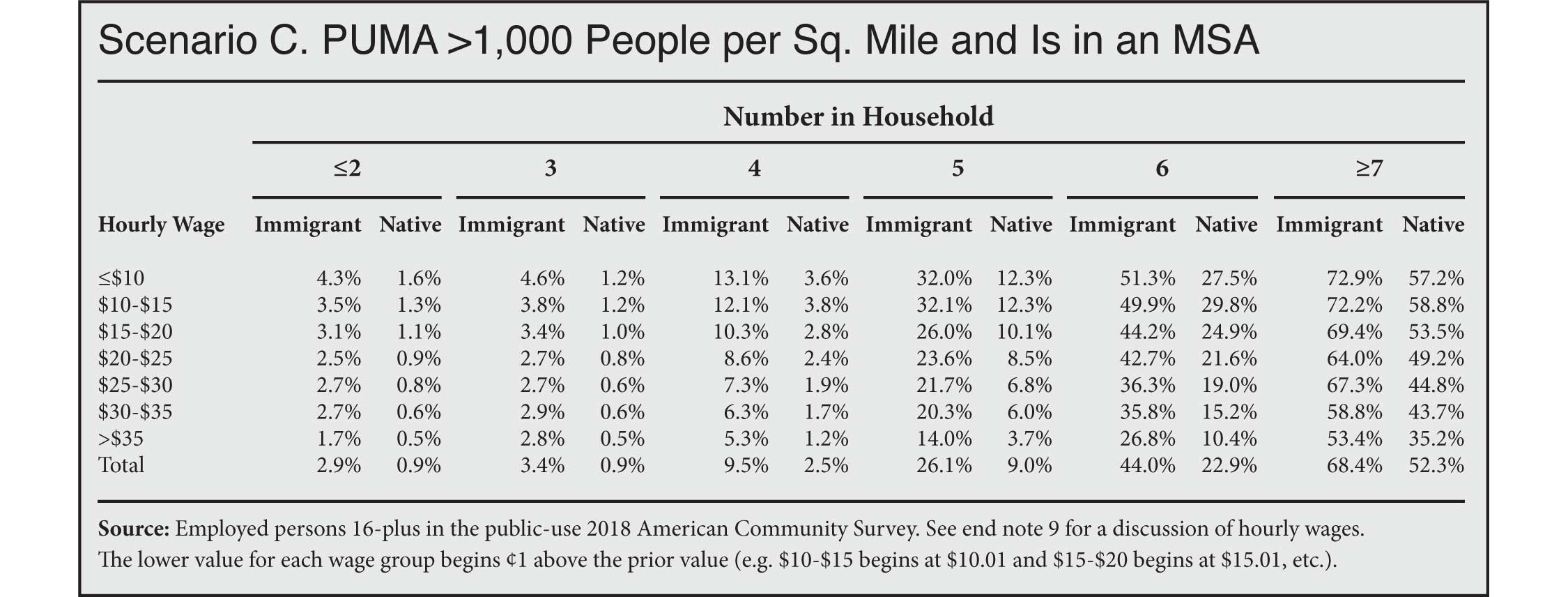

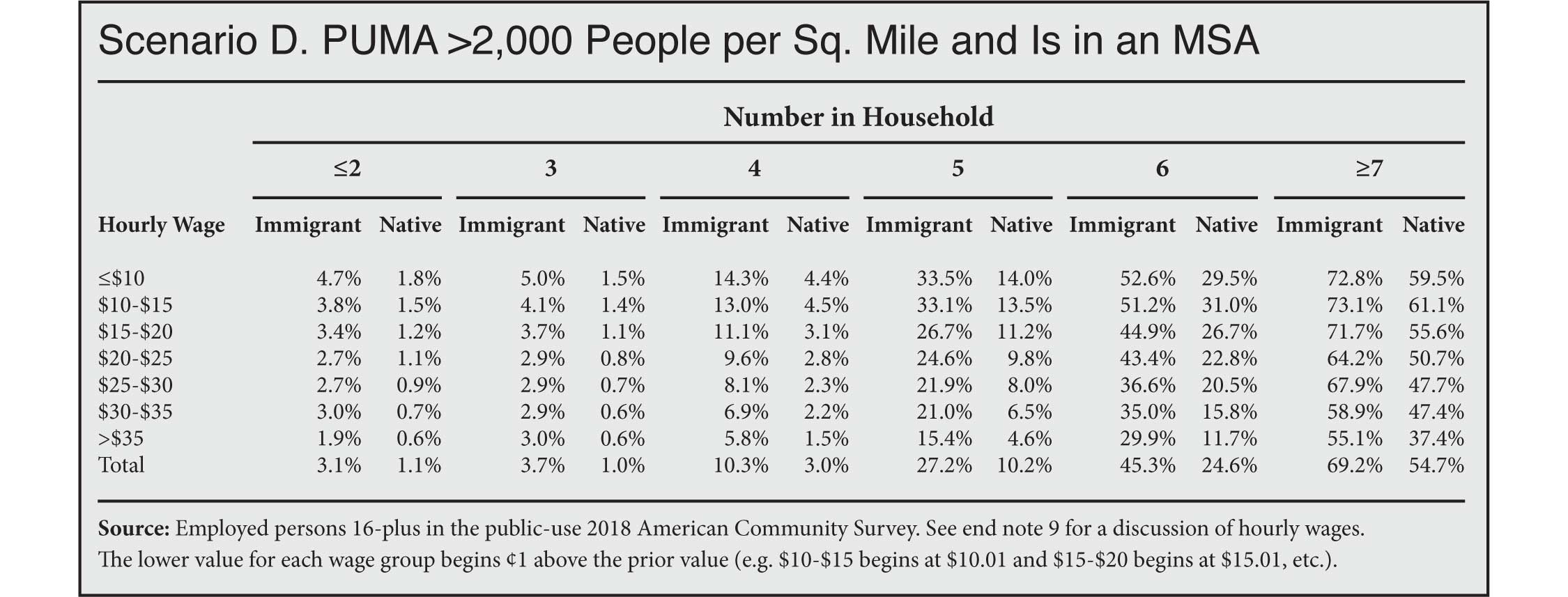

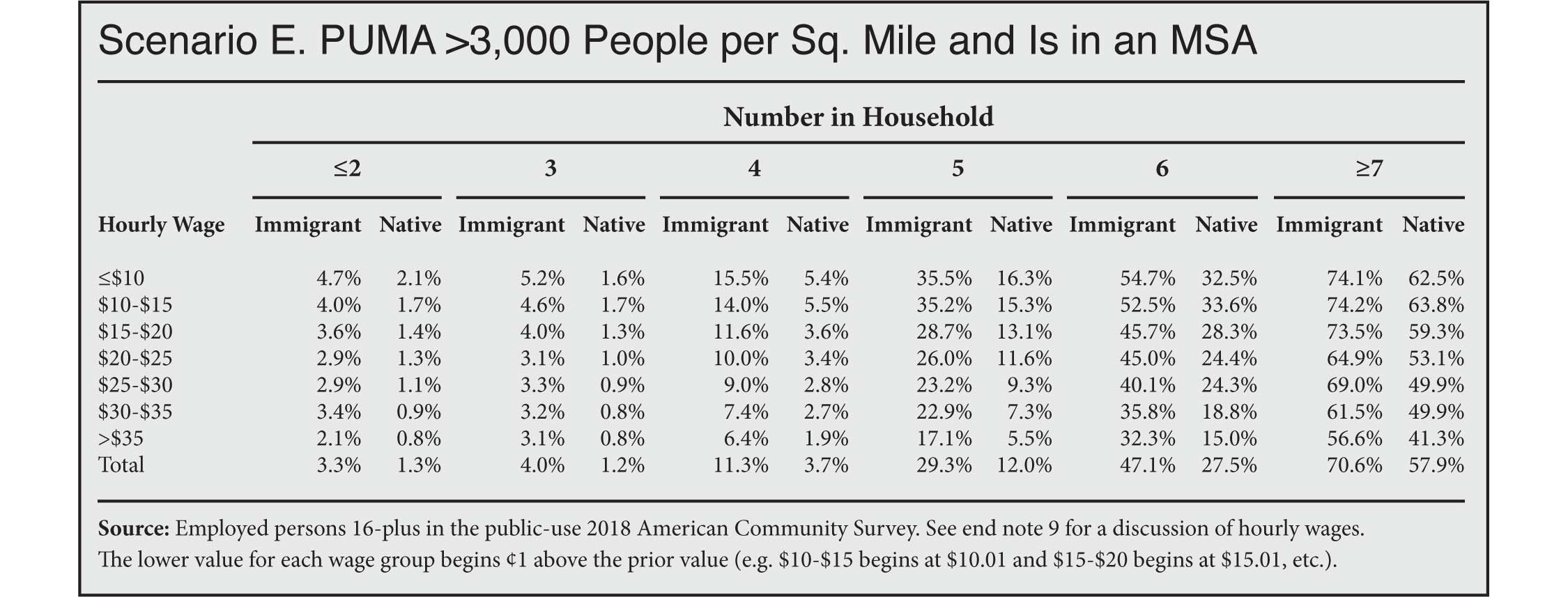

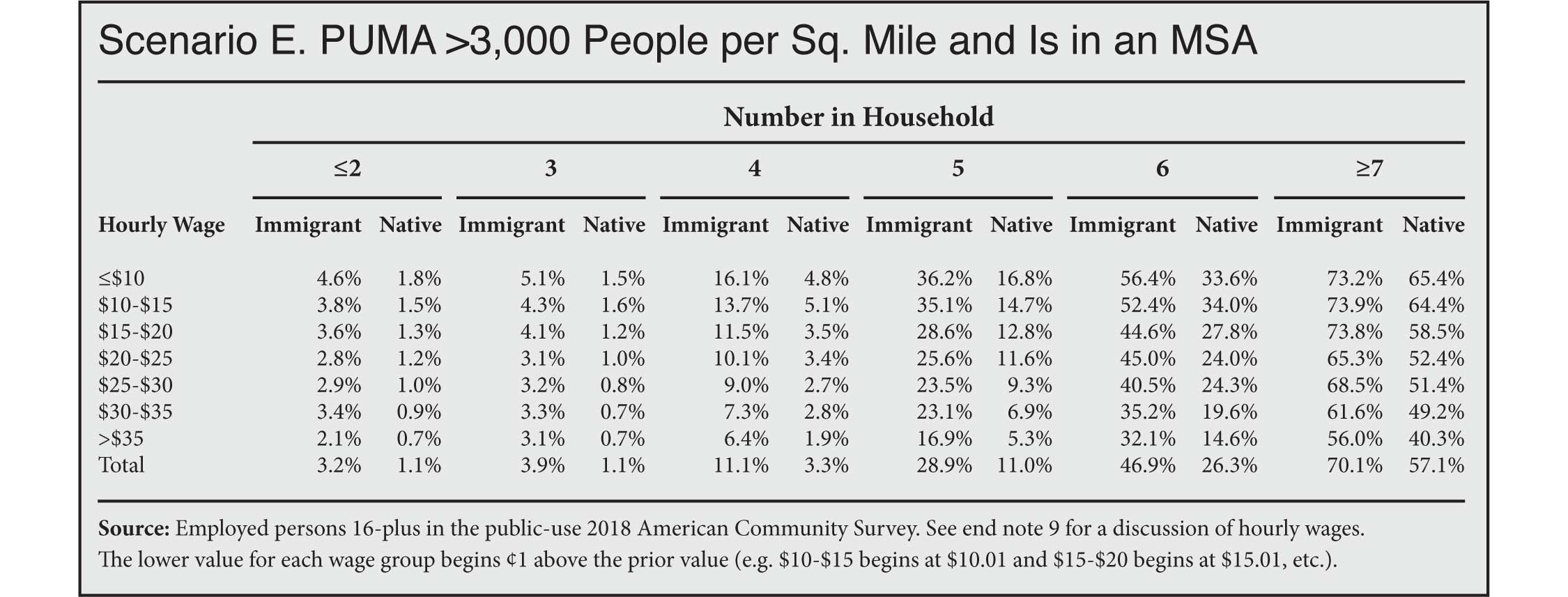

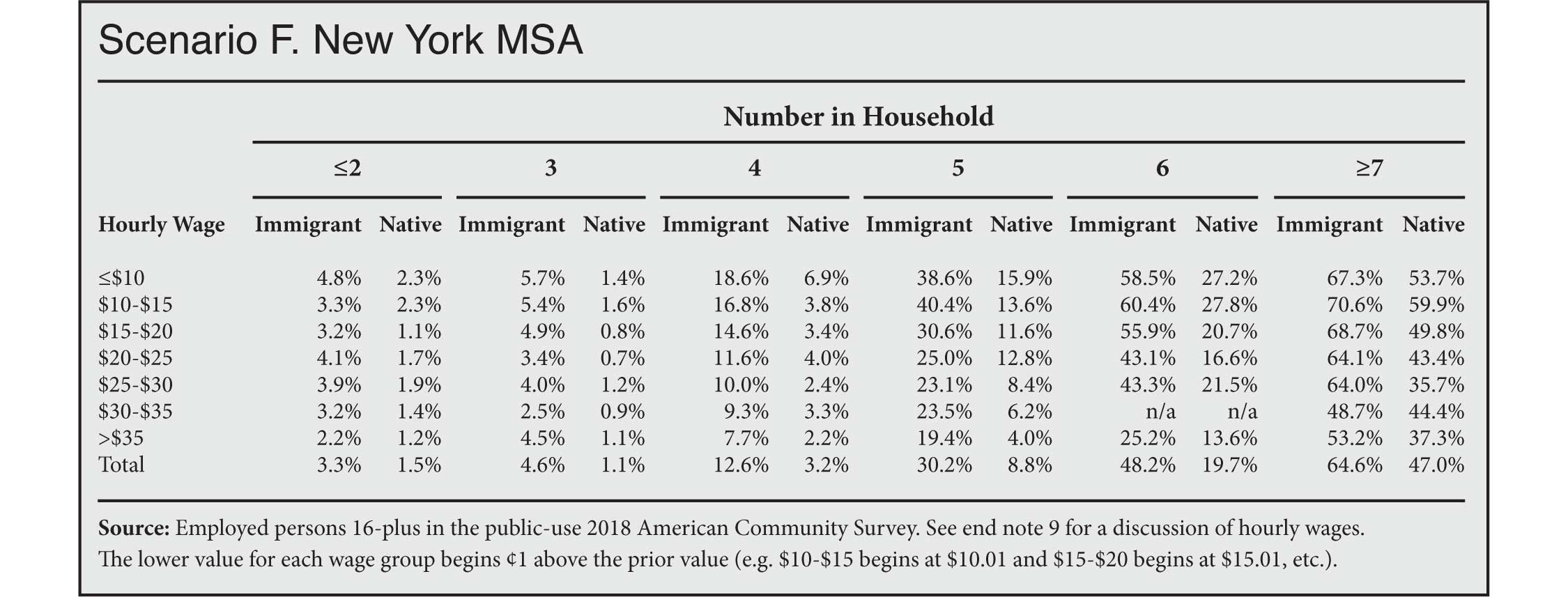

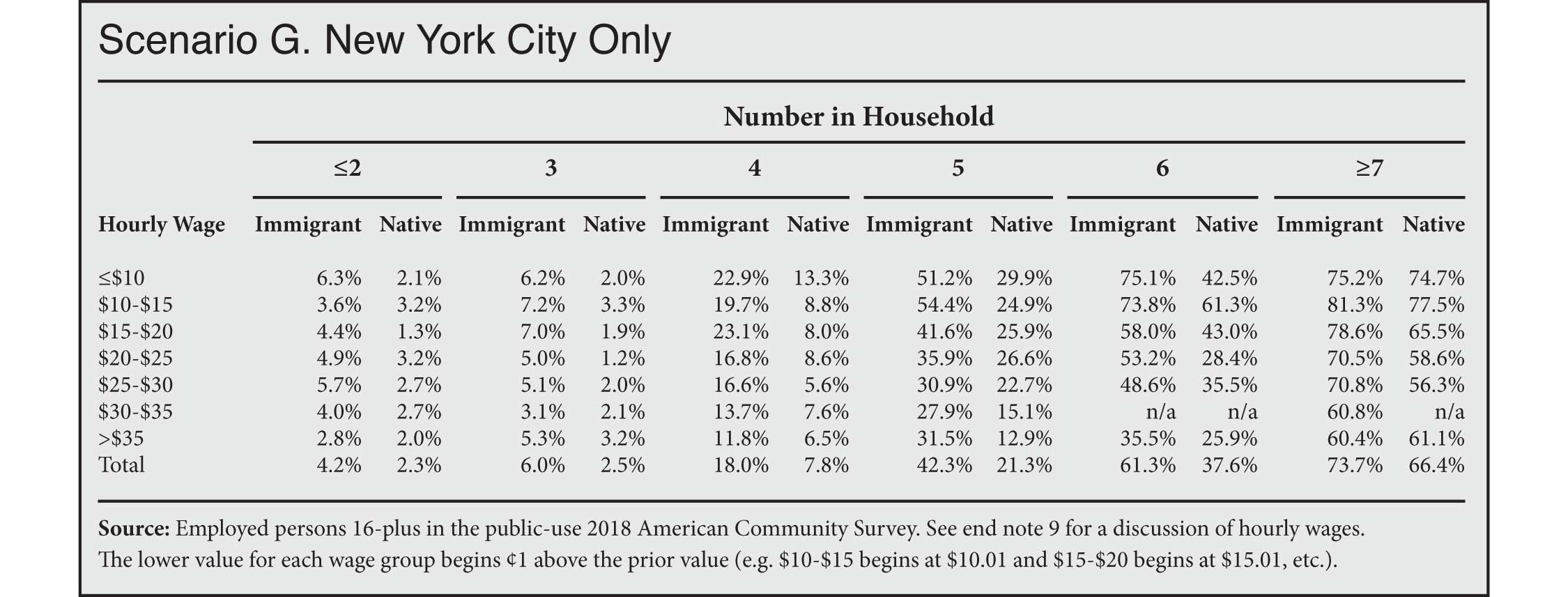

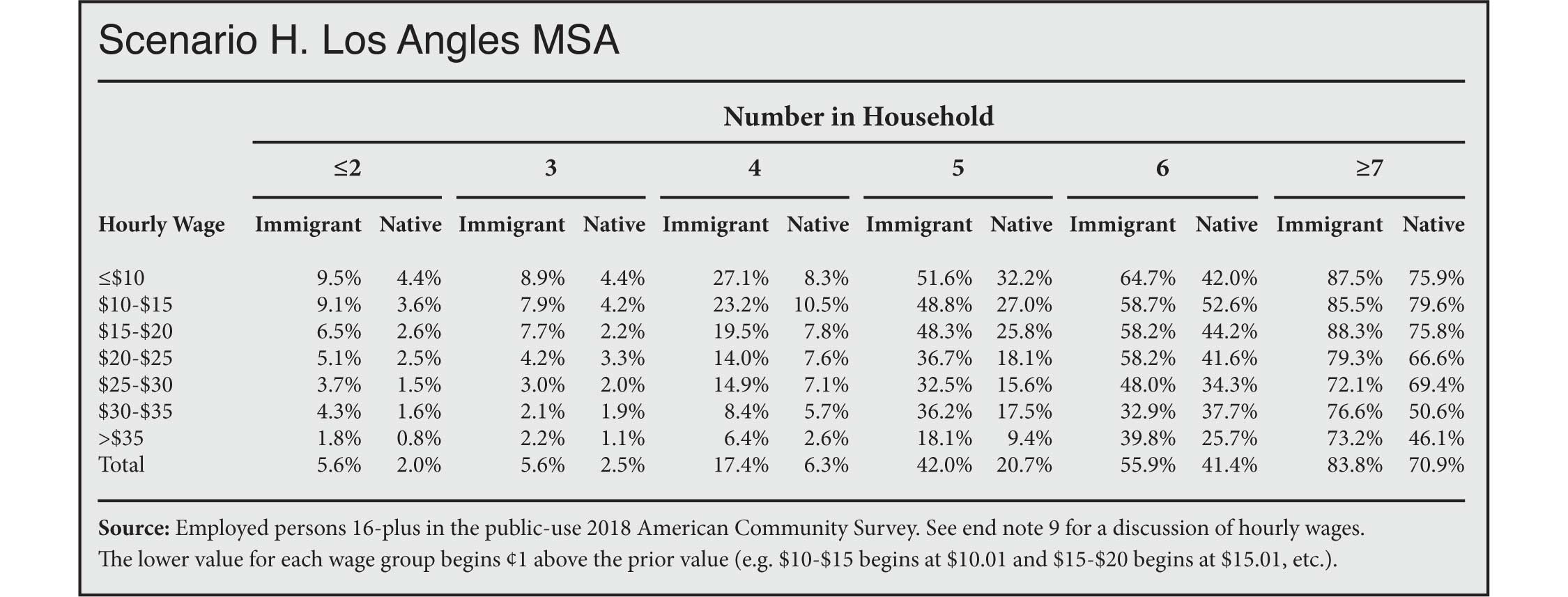

|

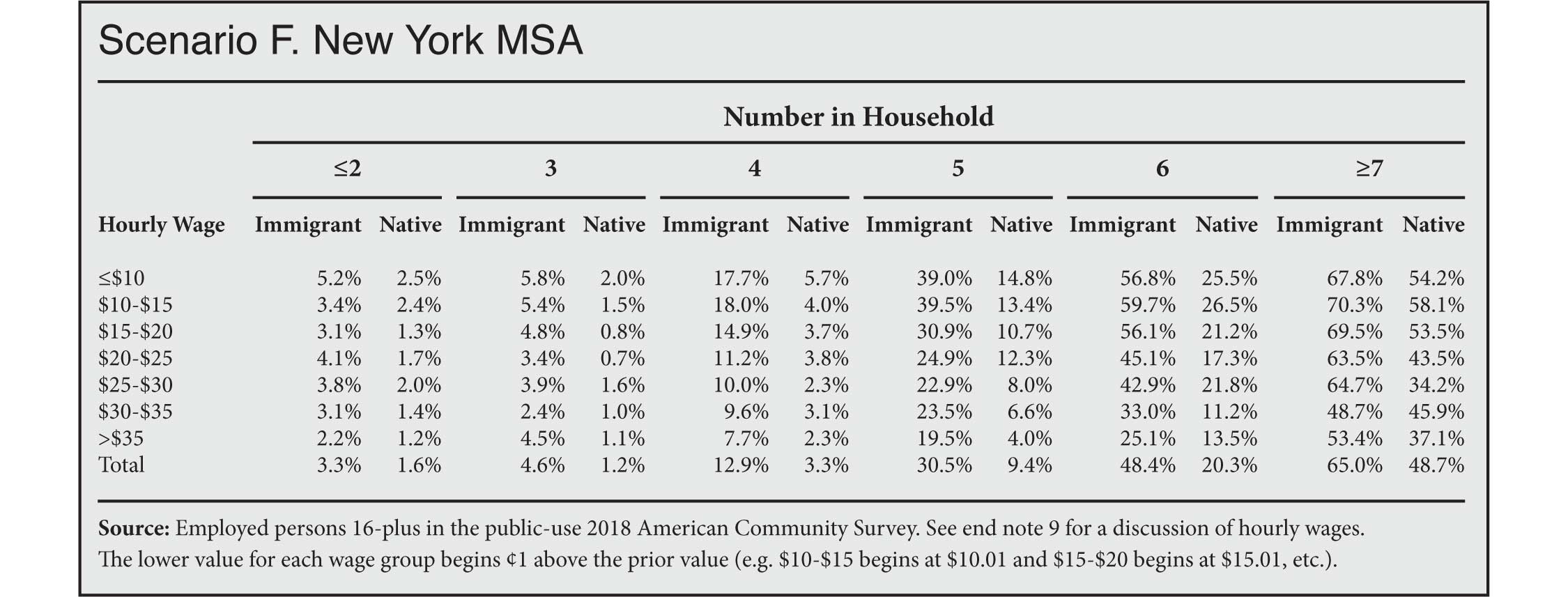

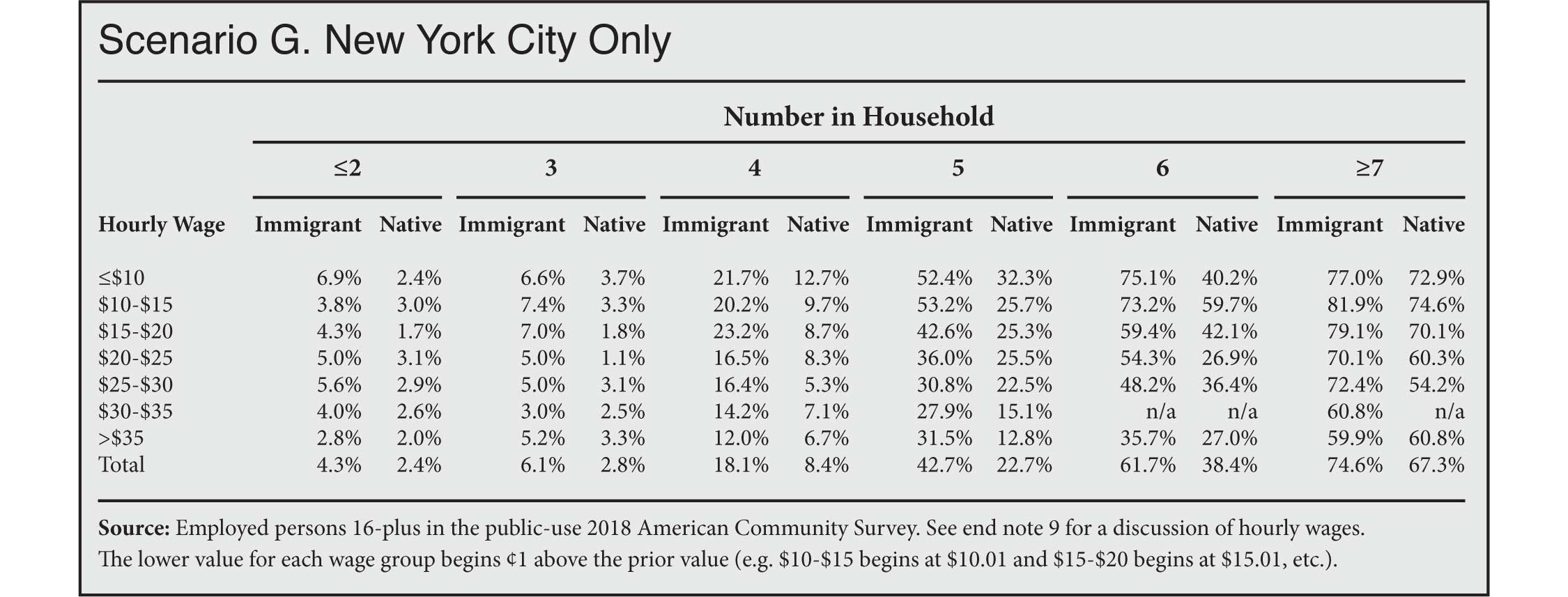

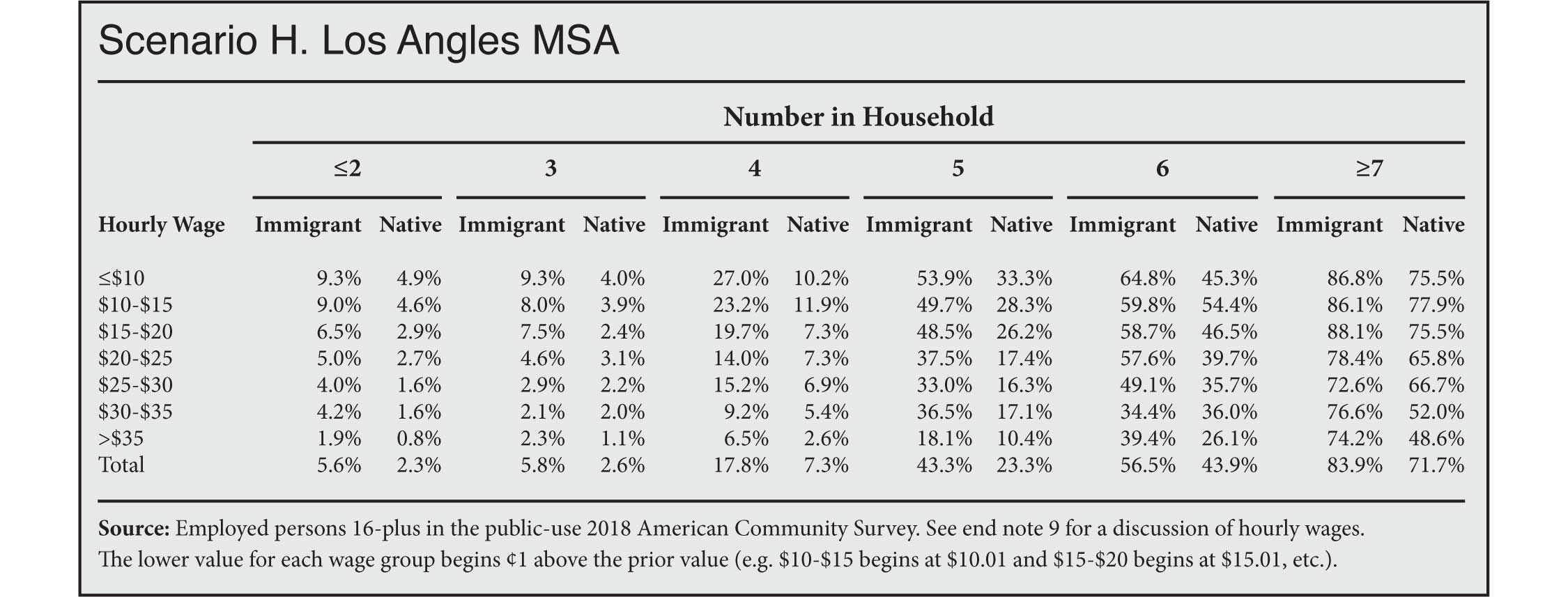

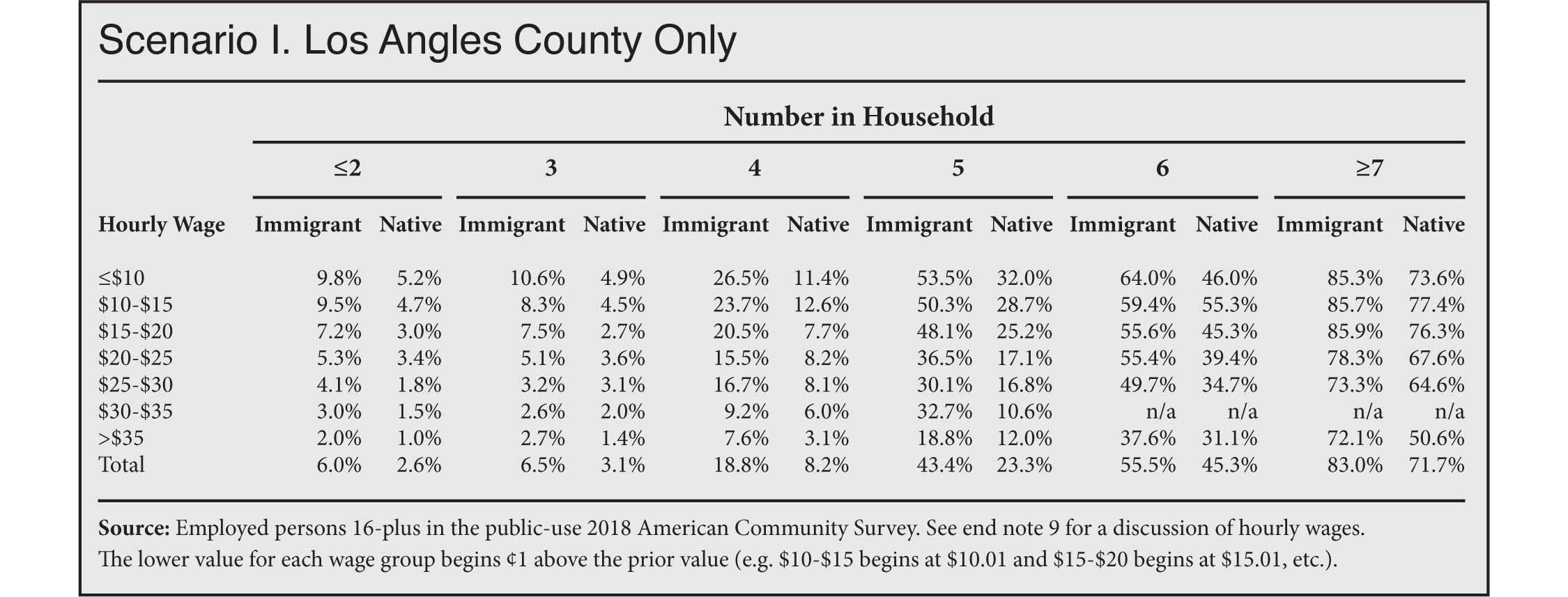

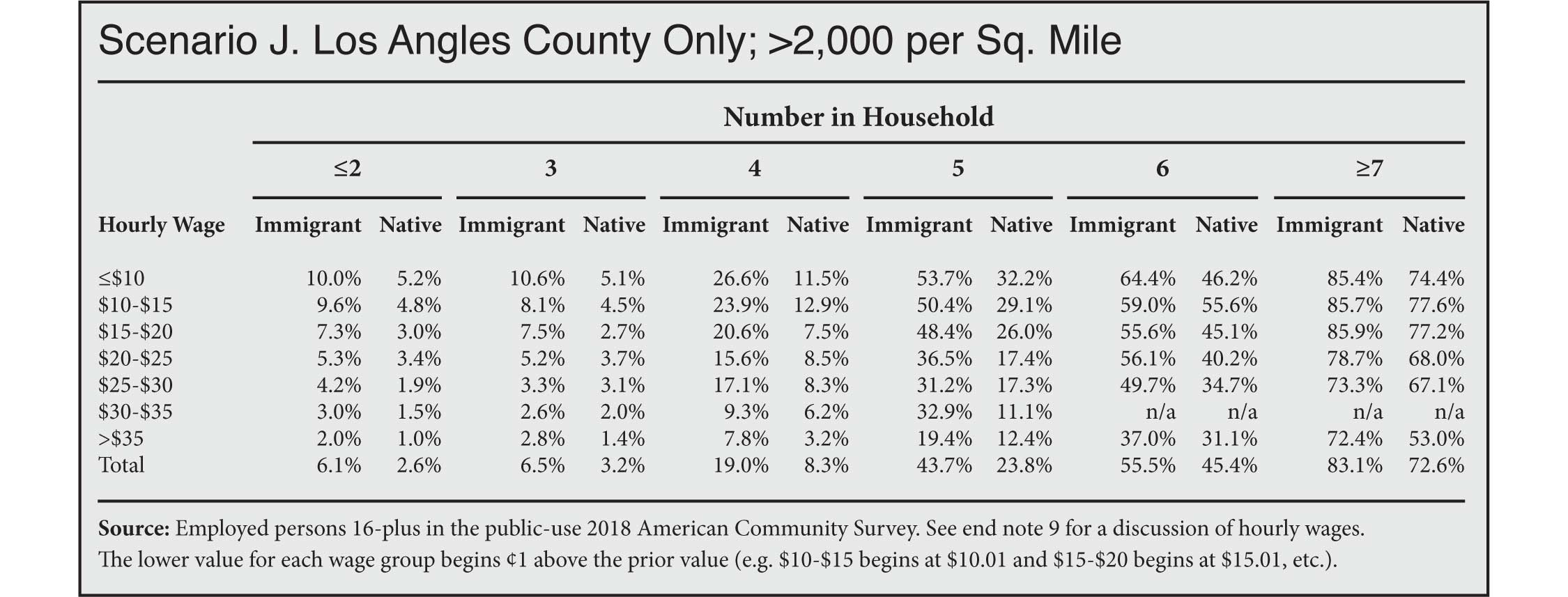

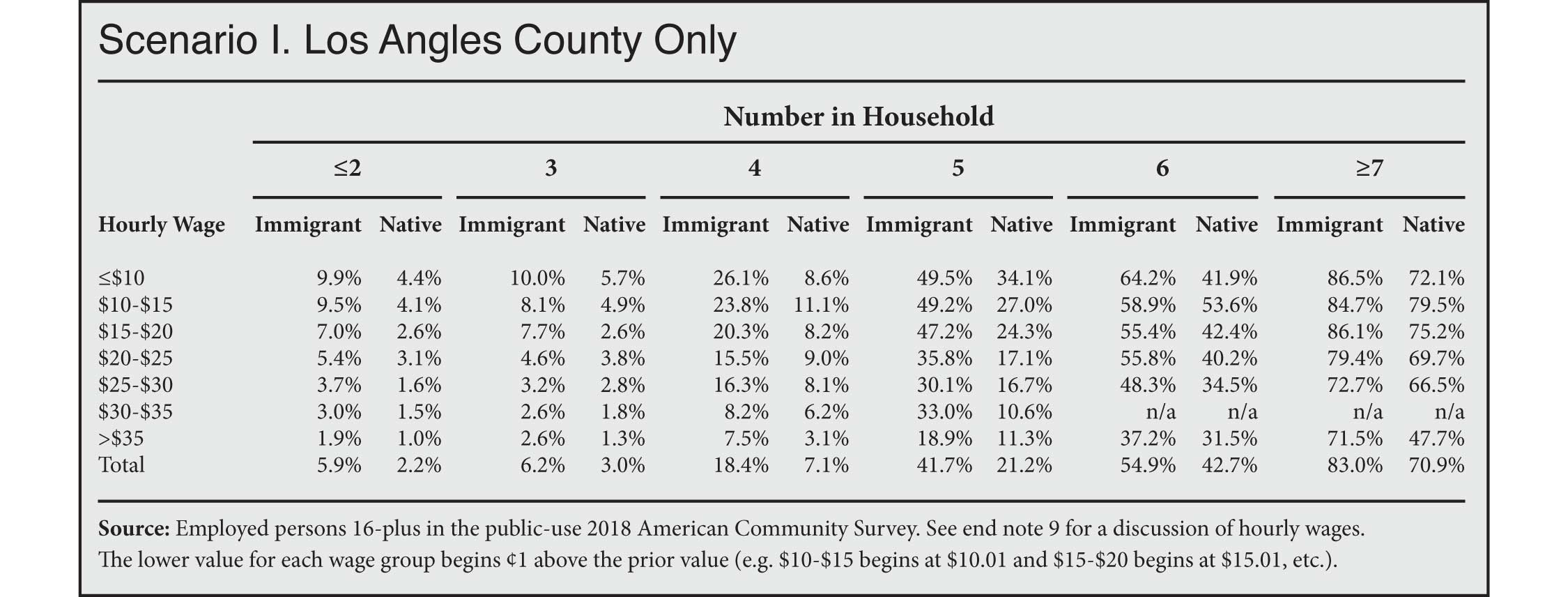

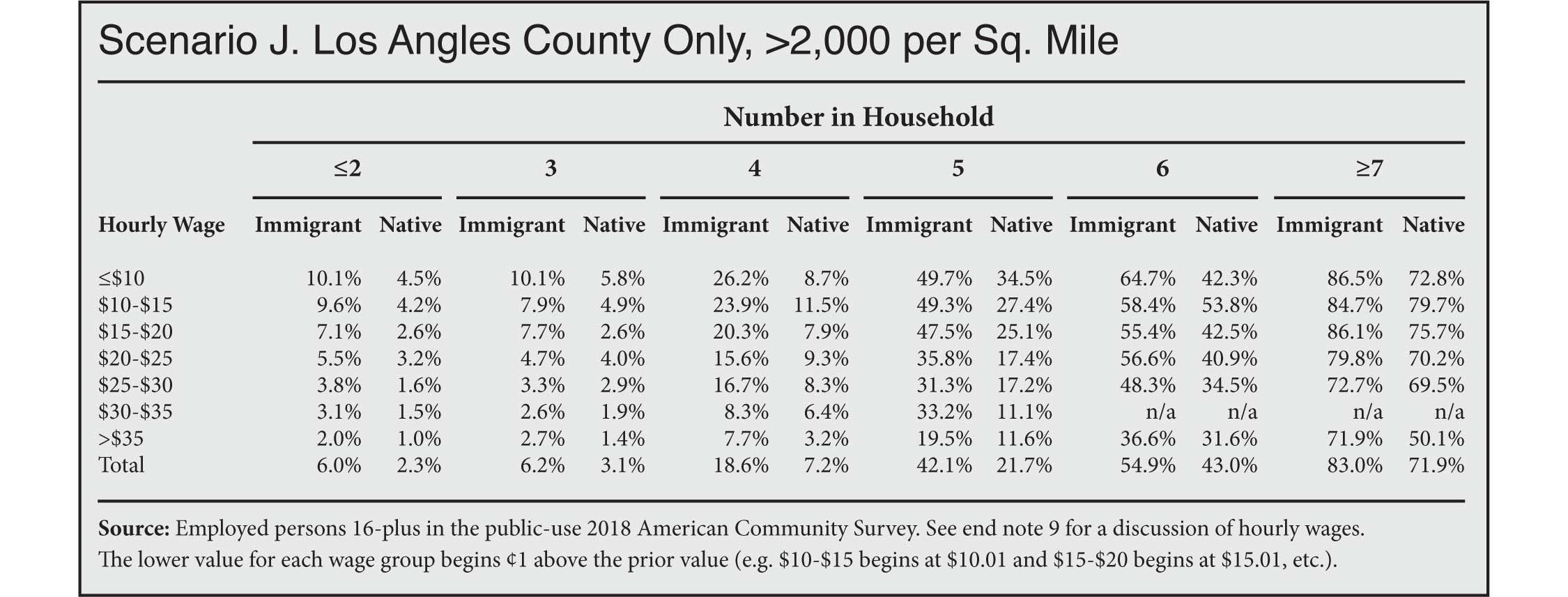

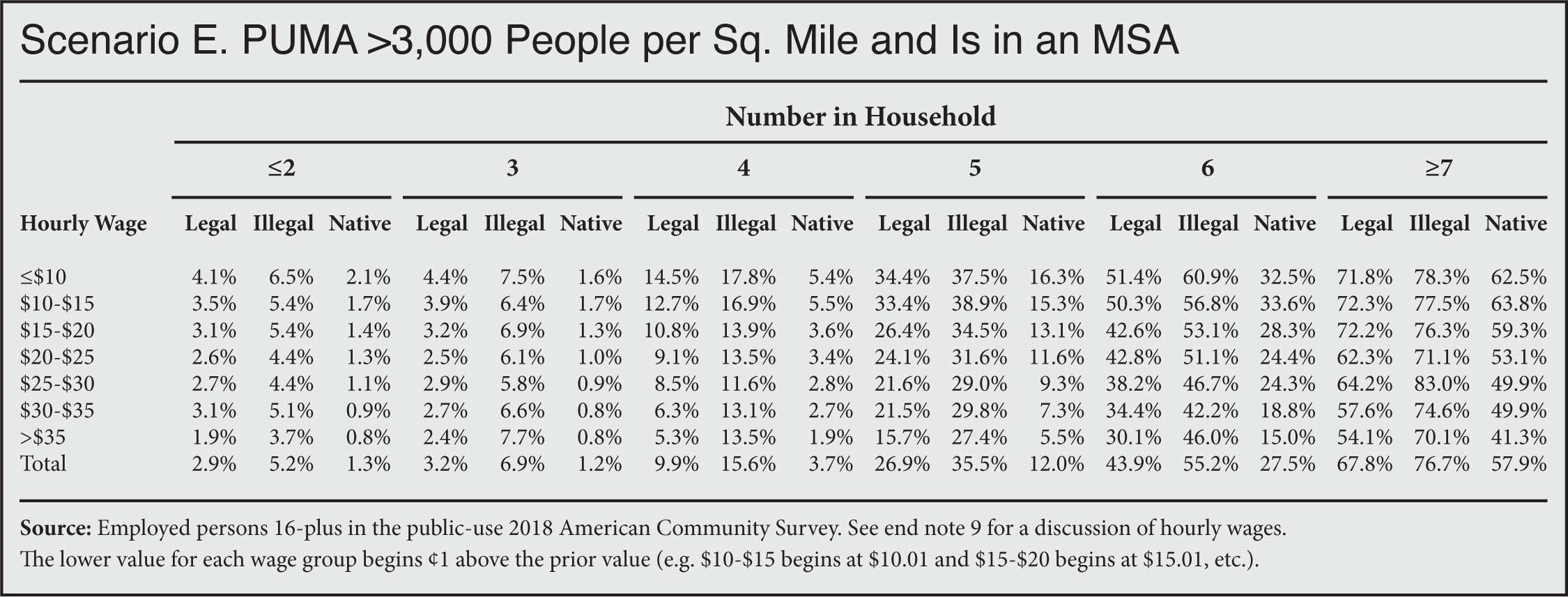

Figures 13and 14 are not fully developed models that explain the large differences in overcrowding between native-born and foreign-born workers. Table A7 in the Appendix reports crowding by more narrow wage intervals than Figure 13, different household sizes, and for areas of different population densities. Scenarios F through J of the table also report overcrowding for the New York and Los Angeles Metropolitan Statistical Areas (MSA), and New York City and Los Angeles County separately. While there are 10 different scenarios in Table A7, in general, the table shows that even when immigrants live in similar circumstances, they are much more likely to live in overcrowded conditions. For example, foreign-born workers who live outside of an MSA in an area with a population density with less than 1,000 people per square mile (Scenario B) are significantly more likely to live in overcrowded housing than native-born workers. In 34 of the 36 comparisons that are possible in Scenario B, immigrants have higher rates of overcrowding. On average, Scenario B shows that the share of immigrant workers in overcrowded housing is 8.9 percentage points higher than for native-born workers. If we look at those PUMAs with a density of 3,000 or more people per square mile in an MSA we find a 9.9 percentage-point average difference even after taking into account wages and household size.

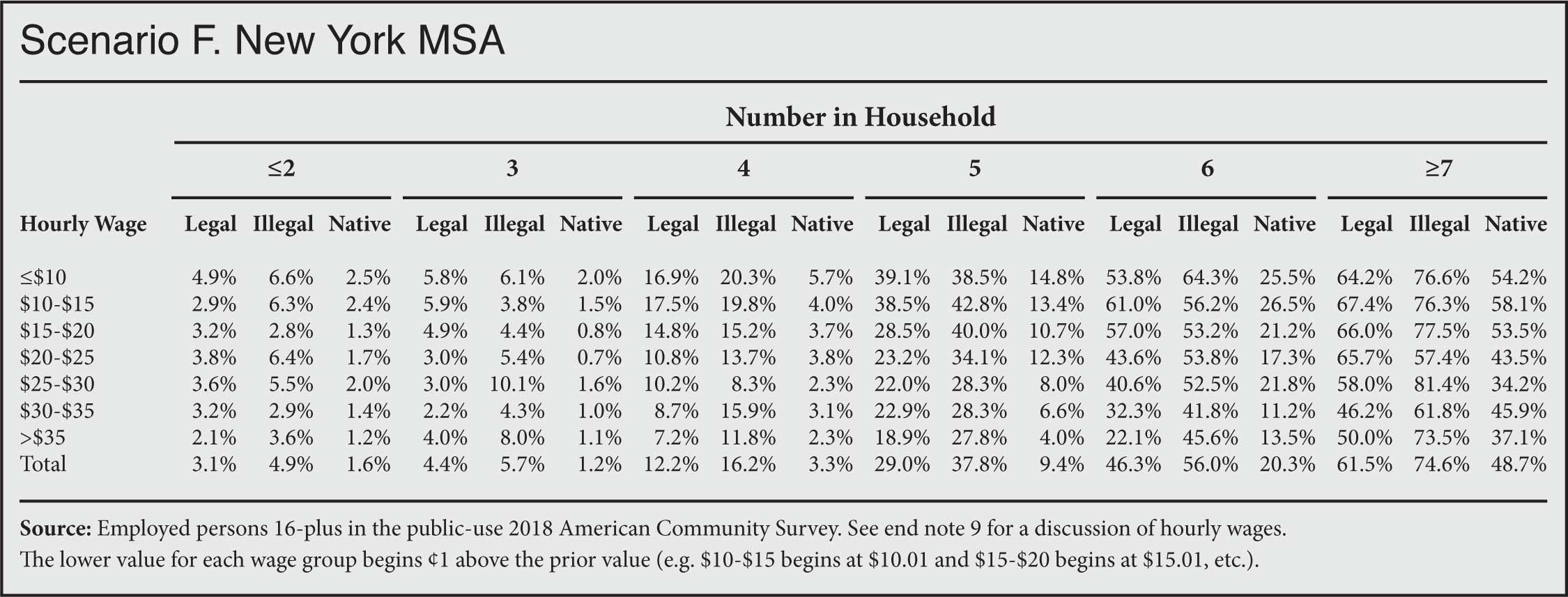

Toward the bottom of Table A7, overcrowding statistics are reported for workers in the New York and Los Angles MSAs, two very high cost of living areas with large immigrant populations. The New York and Los Angles scenarios again show that immigrant workers are much more likely to live in crowded housing even when they live in the same size household and earn similar wages in the same city. For example, immigrant workers in the New York MSA (Table A7, Scenario F) are more likely to live in overcrowded housing in all 42 comparisons that control for wage and household size. When we focus only on New York City (Scenario G) we find a similar pattern, though the differences are not quite as pronounced as when we look at the entire New York MSA.

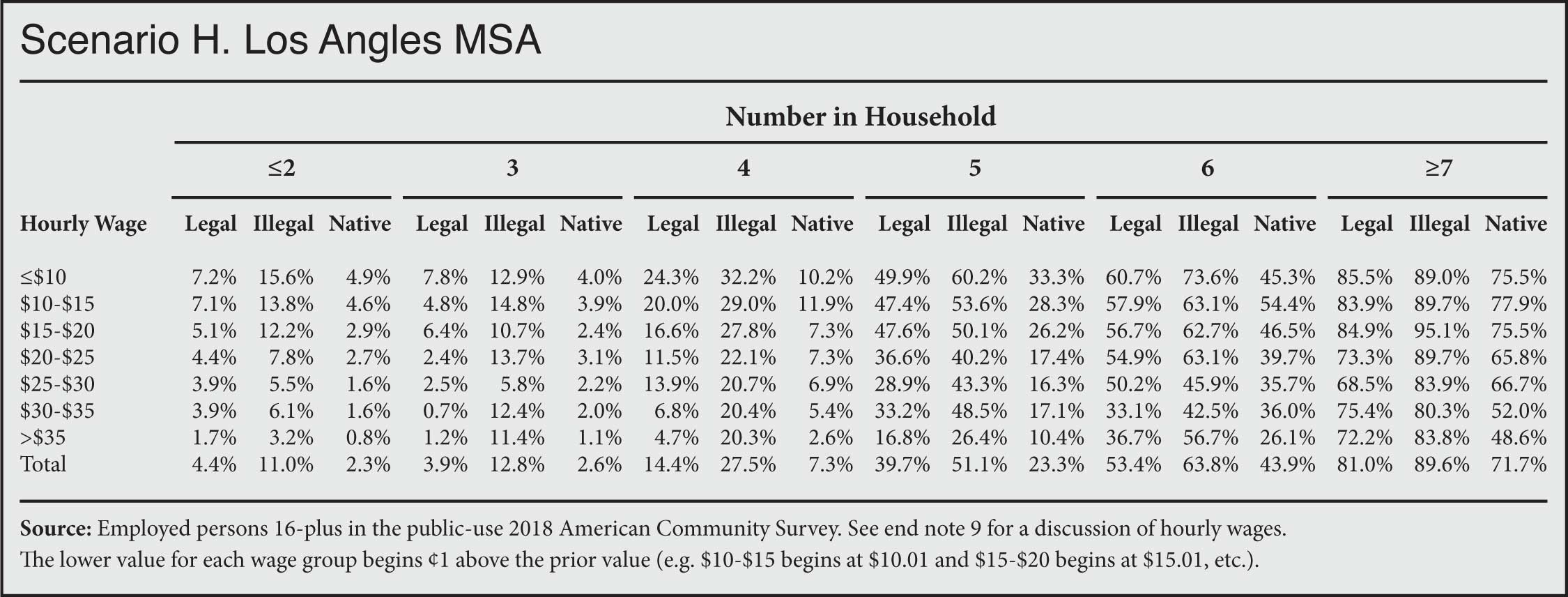

The New York City-only analysis (Scenario G) is particularly interesting because that city has very high housing costs. Despite this, the results in Scenario G show that most of the difference between immigrants and natives remains even when we look at just the city vs. the entire New York MSA.21 When we look at the Los Angles MSA (Scenario H), Los Angeles County only (Scenario I), or only the most densely settled part of Los Angeles County (Scenario J), we find the same pattern as our New York MSA and New York City-only analyses — immigrant workers are much more likely to live in overcrowded conditions even when they live in the same size household and earn roughly the same wages.22 Household size, wages, and settlement in higher cost of living areas do partly explain why immigrant workers are much more likely to live in overcrowded conditions. But clearly large differences remain even when we try and take these things into account.

Excluding Young Workers

A large share of workers employed in some low-wage jobs such as retail or fast food are often young people supported by their parents and therefore may be less likely to live in overcrowded housing despite their low earnings. Because immigrants generally arrive in the United States in their late twenties or early thirties, only 6.2 percent are aged 16 to 24, compared to 13.6 percent of native workers.23 It is possible that part of the reason low-wage native workers are less likely to live in overcrowded housing compared to low-wage immigrant workers is that immigrants are older workers supporting themselves, while a significant share of low-wage native-born workers are supported by their parents.

Table A8 in the appendix tests this argument by using the same scenarios as Table A7, except that it excludes all young people by confining the analysis to only workers 25 and older. Overall, the various scenarios in Table A8 show the same pattern as Table A7 that included young people. For example, in rural areas (Scenario B) in Table A8, which excludes young people, immigrant overcrowding is 8.6 percentage points higher on average in the 36 comparisons that can be made. In the same scenario in Table A7, which includes young workers, the share of foreign-born workers living in overcrowded housing is 8.9 percentage points higher on average than native-born workers. The other scenarios show the same general pattern. The inclusion of young people does not explain the large difference between foreign-born and native-born workers in overcrowding.

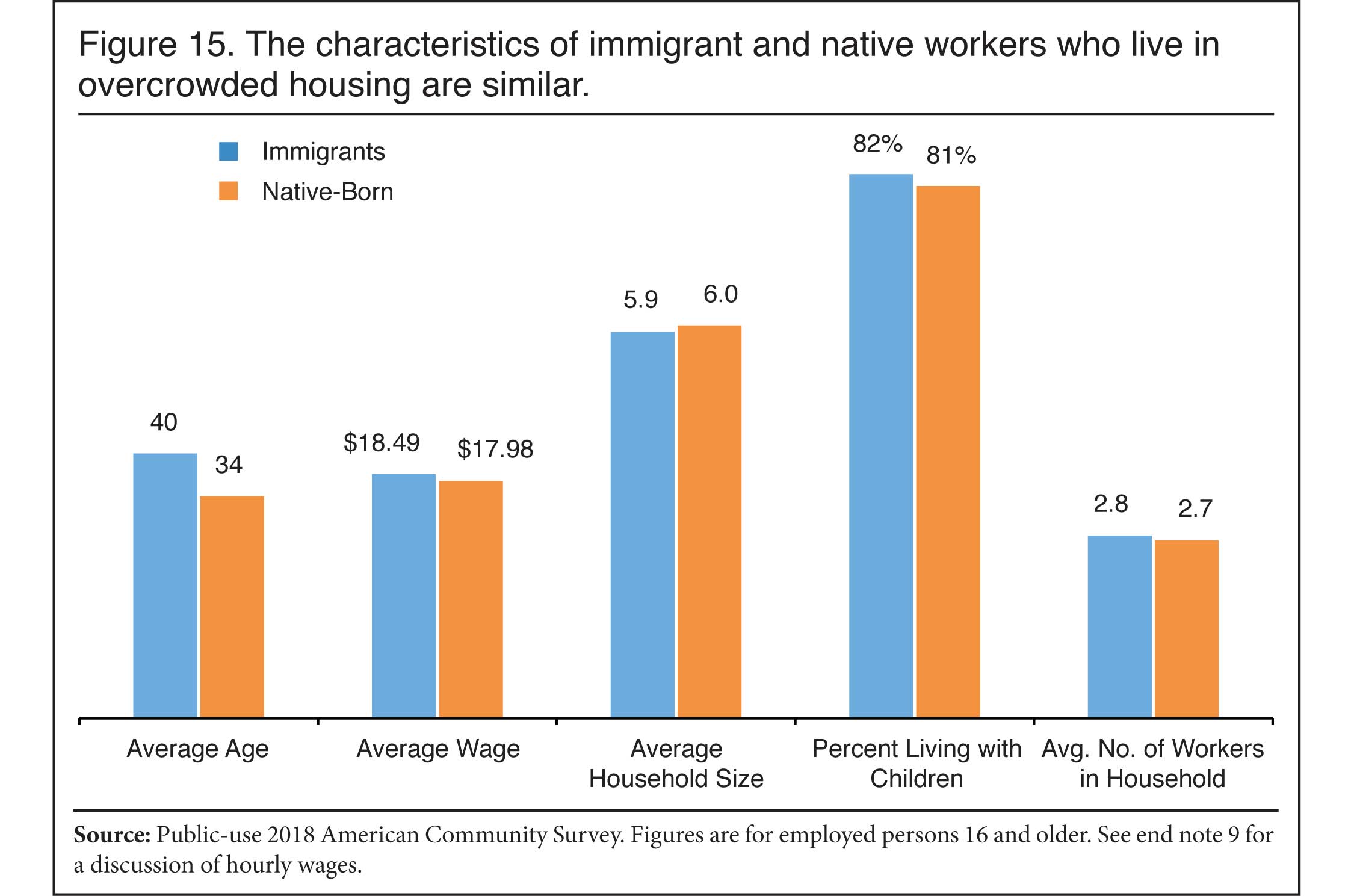

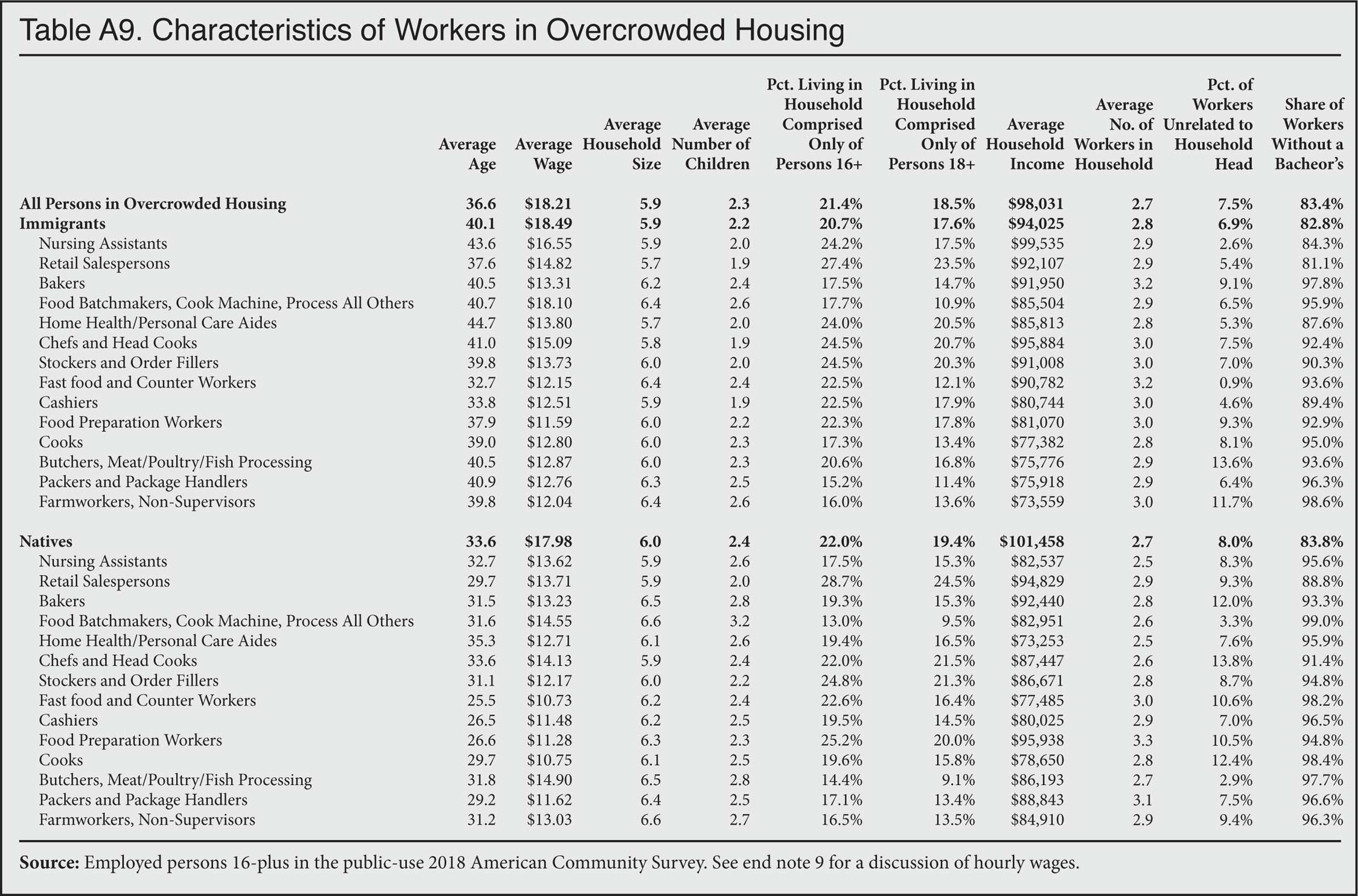

Characteristics of Those in Overcrowded Housing

Figure 15 shows that, in general, immigrant and native workers who live in crowded housing have very similar characteristics, with the exception that the native-born tend to be relatively younger, averaging 34 years of age on average compared to 40 years for immigrant workers. This may partly reflect the fact that the average immigrant worker is about two years older than the average native worker. Moreover, as already pointed out, a significantly larger share of all native-born workers are young, under age 25, than immigrant workers. As already mentioned, this is because immigrants generally arrive in their late 20s or early 30s, while native-born workers typically start work in their teens or early 20s. So it may not be that unexpected that native-born workers in overcrowded housing are younger than immigrant workers.

|

Figure 15 also indicates that the hourly wage of immigrants and native workers in overcrowded housing is similar, as is the number of people in the household and the share living with one or more children. Appendix Table A9 provides additional information about workers living in overcrowded conditions by occupation.24 In general, Figure 15 and Table A9 show that overcrowded households are large in size and are comprised of related people, typically with children present, in which the workers earn modest wages, though there are nearly three workers per household on average. It also shows that the vast majority of these workers do not have bachelor’s degrees. All of this is true for both immigrant and native workers living in overcrowded households.

Special notice may be paid to the fact that Table A9 shows that, for the most part, workers in overcrowded housing are typically related to the household head — 93 percent for immigrants and 92 percent for natives. However, it is true that in some occupations a relatively large share of workers in overcrowded conditions is unrelated to the household head. For example, only 86 percent of immigrant butchers and meat processors who live in overcrowded conditions are related to the household head. Still, the vast majority of immigrant workers in this occupation living in crowded conditions are related to the household head. This would seem to indicate that, in general, those who are employed in this occupation and live in overcrowded conditions are living with family members. It is also the case that 82 percent of immigrant workers in overcrowded housing live with children, basically the same as the 81 percent of native workers living in crowded conditions. So the stereotype of many unrelated adult immigrant workers crowded into one housing unit does not seem to be correct.

Legal Status

It is well established that illegal immigrants do respond to Census Bureau surveys such as the ACS used here. To determine which respondents in the survey are most likely to be illegal aliens, CIS first excludes immigrant respondents who are almost certainly not illegal aliens.25 The remaining candidates are weighted to replicate known characteristics of the illegal population (population size, age, gender, region or country of origin, state of residence, and length of residence in the United States).26 We use the illegal estimates developed by the Center for Migration Studies (CMS), which are based on the 2018 ACS.27 The resulting illegal population, which consists of a weighted set of ACS respondents, is designed to match CMS on the characteristics listed above. However, we do not adjust the number of illegal immigrants for undercount in the ACS.28 Estimates for legal immigrants are calculated simply by subtracting estimated counts of illegal immigrants from the total immigrant population in the survey.

Like any estimate of illegal immigrants, ours comes with some important caveats. Looking at illegal immigrants captured in Census Bureau surveys provides useful insight into this population; however, such estimates contain both sampling error, which exists in any survey, and non-sampling error and should therefore be interpreted with caution. This is especially true because we use employment in some occupations as an indication of legal status and at the same time we report estimates by occupation. Nevertheless, our estimates represent our best estimate of illegal immigrants and are consistent with what other researchers have found.

Table 2 reports our estimates for the share of legal and illegal immigrants in crowded housing overall and for specific occupations. The right side of Table 2 shows the share of all workers in the occupation living in crowded conditions who are legal or illegal immigrants. So the table reads as follows: Of legal immigrant workers employed on farms in non-supervisory jobs, 30.2 percent live in overcrowded conditions and 29.9 percent of illegal immigrant farmworkers live in overcrowded conditions, as do 8.3 percent of native-born workers in the occupation. The right side of the table shows that legal immigrants account for 34.3 percent of all farmworkers in crowded conditions and illegal workers account for 42.0 percent. The bottom of Table 2 shows that, overall, 12.1 percent of legal immigrant workers live in crowded conditions compared to 21.5 percent of illegal immigrant workers. But legal immigrants account for a much larger share (30 percent) of all workers in overcrowded conditions compared to illegal immigrants (16.1 percent) because legal immigrants are much more numerous.29

|

Appendix Tables A1, A2, and A5 report additional information by legal status for broad occupational categories and more specific occupations. Table A5 indicates that illegal immigrant workers earn somewhat less than legal immigrants in the same occupation in some cases. But in the 14 specific occupations that are the focus of this analysis, the average hourly wage is only 8 percent lower than it is for legal immigrants. As already mentioned, when we compare immigrants overall (legal and illegal) to natives, we generally find that those in the same occupations typically earn wages that are not very different. To be sure, Table A5 indicates (at the bottom of the table) that illegal immigrants overall earn much less than either native-born or legal immigrant workers on average. Their lower average hourly wage reflects their much lower levels of educational attainment, resulting in their concentration in lower-paying jobs that require relatively modest levels of schooling. But lower overall average wages do not explain why illegal immigrant workers are so much more likely to live in crowded housing even when they earn roughly the same wages as native workers in the same occupations.

Table A10 is similar to Tables A7 and A8 in that it reports overcrowding by wage, household size, and population density, except that it also reports figures by legal status. While the number of scenarios is more limited in Table A10 due to sample size issues, it still shows illegal immigrants have higher rates of overcrowding than legal immigrants or native-born workers even taking into account wages, household size, and population density. This may not be too surprising. But the relatively high rates of overcrowding for legal immigrants relative to natives, even when controlling for these factors, maybe unexpected.

As already discussed, we estimate that 12.1 percent of all legal immigrant workers live in overcrowded housing compared to 3.5 percent of native-born workers — an 8.6 percentage-point difference. Table A10 shows this gap remains, for the most part, even when we take into account wages, household size, and population density. In Table A10 Scenario E, which reports figures only for workers in PUMAs with over 3,000 people per square mile, the average difference between natives and legal immigrants across the 42 comparisons is 8.4 percentage points, similar to the gap when comparing legal immigrants to natives without taking into account other variables.

Of course, like our prior analyses of this kind, Table A10 does not take into account all the possible differences between legal and illegal immigrants or legal immigrants and the native-born that might explain overcrowding. However, what we can say is that even when we try to control for some of the most important factors associated with overcrowding, legal immigrant workers are still much more likely to live in overcrowded conditions than the native-born. Moreover, there are almost twice as many legal immigrant workers living in overcrowded conditions as there are illegal immigrant workers.

Conclusion

Our analysis indicates that overcrowding is much more pronounced among immigrant workers (14.3 percent) than their native-born counterparts (3.5 percent). Immigrants account for nearly half of workers living in overcrowded conditions, but only about 17 percent of all workers. This is a concern because research shows that overcrowding can facilitate the spread of communicable diseases, including some new research on Covid-19. Since the Covid-19 outbreak, there have been a number of incidents of employees in the sectors examined in detail in our report having contracted Covid-19 resulting in the shutdown of facilities. The high incidence of overcrowding among workers in these sectors may be playing a role in spreading Covid-19. Of course, it would be unfair to assume that immigrants caused the spread of Covid-19 in all of these facilities. What we can say is that overcrowding is common among workers in these industries, particularly among immigrants. And, prior research indicates crowding facilitates the spread of infections like Covid-19. In addition to the spread of disease, overcrowding can also strain infrastructure and create other problems.

Somewhat surprisingly, our analysis shows that even when their wages, household size, and the population density of the areas in which they live are similar, both legal and illegal immigrant workers are much more likely to live in crowded conditions than their native-born counterparts. For example, an immigrant worker over age 25, making less than $10 an hour, living with five other people in an urbanized area is much more likely to live in an overcrowded home than a native-born worker with those same characteristics. This does not mean wages, household size, or settlement in urban areas do not matter. Immigrants tend to earn lower wages, live in larger households, and are more likely to live in high-cost-of-living urban areas. But even when these things are taken into account, immigrant workers are still much more likely to live in overcrowded housing than comparable native-born workers, meaning that other factors must contribute to immigrants’ high rates of overcrowding.

Immigrants (the "foreign-born") in the Census Bureau data used in this analysis include both legal immigrants and those in the country illegally. We estimate that 12.1 percent of legal immigrant workers live in crowded conditions, compared to 21.5 percent of illegal immigrant workers. But legal immigrants account for a much larger share (30 percent) of all workers in overcrowded conditions compared to illegal immigrants (16.1 percent) because legal immigrants are much more numerous. As is the case with immigrants overall, when we take into account wages, household size, and residence in an urban area, we find that both legal and illegal immigrants are still much more likely to live in overcrowded housing than comparable native-born workers.

The high rate of overcrowding among immigrant workers, even after accounting for wages, household size, and population density should not be seen as a moral issue. While more research is needed, cultural preferences about personal space and expectations about home size likely play some role in explaining why immigrants are much more likely to live in overcrowded housing. A very large share of immigrants come from developing countries where homes are generally much smaller than in the United States. So it should not be too surprising if they often choose to live in more moderately sized homes, saving money, and spending it on something else.

Immigrants’ desire to spend less on housing so they can send money back to their home countries may also contribute to their living in overcrowded housing. The ability to send remittances to their families in the countries from which they came is one of the primary reasons some immigrants come to the United States. The World Bank estimated that $68 billion in remittances were sent from the United States in 2018.30 The vast majority of this money comes from immigrants and likely represents a significant share of income for immigrants who send money abroad.31

The decision to allow in large numbers of immigrants, especially to fill low-wage jobs, has increased overcrowding significantly in the United States. Therefore, reducing future immigration would directly reduce overcrowding over time. We also find that overcrowding declines significantly with higher wages, particularly for immigrants. In addition to lessening immigration's direct impact on overcrowding, lower levels of future immigration could help reduce crowding by exerting upward pressure on wages. Other policies designed to raise wages, such as increasing the minimum wage, strengthening unions, and more robust enforcement of fair labor practices should also be considered.

Appendix

|

|

|

|

|

|

Table A7. Overcrowding for Immigrant and Native-Born Workers by Wage, Household Size and Population Density

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

Table A8. Overcrowding for Immigrant & Native-Born Workers Ages 25 & Older by Wage, Household Size, & Population Density

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

Table A10. Overcrowding by Legal Status, Wage, Household Size, and Population Density

|

|

|

|

End Notes

1 The Department of Housing and Urban Development has compiled a detailed summary of the overcrowding literature and the various ways to measure it. See Kevin S. Blake, Rebecca L. Kellerson, and Aleksandra Simic, “Measuring Overcrowding in Housing”, prepared for the U.S. Department of Housing and Urban Development Office of Policy Development and Research, 2007.

2 The Census Bureau records the number of rooms for each housing unit as part of the annual ACS by asking respondents: “How many rooms are in this house, apartment or mobile home?” The question provides a good deal of detail to those taking the survey about how rooms are defined, such as, “Rooms must be separated by built-in archways or walls that extend out at least 6 inches and go from floor to ceiling.” It also includes the instruction to exclude, “bathrooms, porches, balconies, foyers, halls, or unfinished basements”.

3 After reviewing 30 studies in the public health literature on risks associated with non-TB respiratory diseases and overcrowding, the World Health Organization (WHO) stated in 2018 that, “Across the majority of studies on non-TB respiratory diseases, the risk of acquiring the diseases was associated with crowding.” It goes on to state that, “the certainty of the evidence that reducing crowding would reduce the risk of non-TB respiratory disease was assessed as moderate to high, depending on the disease.” “Who Housing And Health Guidelines”, 2018, p. 26. In terms of tuberculosis, WHO reviewed 21 studies and concluded that the certainty that crowding increased the risk of the disease spread was “high”.

4 Recent studies in the United States that have found a link between overcrowding and influenza hospitalization include: Kimberly M. Yousey-Hindes and James L Hadler, “Neighborhood Socioeconomic Status and Influenza Hospitalizations Among Children: New Haven County, Connecticut, 2003-2010”, American Journal of Public Health, September 2011, pp. 1785-9. Chantel Sloan, Rameela Chandrasekhar, Edward Mitchel, William Schaffner, and Mary Lou Lindegren, “Socioeconomic Disparities and Influenza Hospitalizations, Tennessee, USA”, Emerging Infectious Diseases September 2015. Rameela Chandrasekhar et al. “Social determinants of influenza hospitalization in the United States”, Influenza and Other Respiratory Viruses, November 2017, pp. 479–488. Researchers tend to focus on hospitalizations rather than cases because hospitalizations reliably and accurately measure the extent of the disease.

5 Mark Melnik and Abby Raisz, "2020 Greater Boston Housing Report Card", University of Massachusetts Donahue Institute, July 14, 2020. Also see Ukachi N. Emeruwa, Samsiya Ona, Jeffrey L. Shaman, et al., “Associations Between Built Environment, Neighborhood Socioeconomic Status, and SARS-CoV-2 Infection Among Pregnant Women in New York City”, Research Letter, Journal of the American Medical Association, August 2020. An early analysis by the Furman Center at NYU also found that the prevalence of Covid-19 in New York City was highest in zip codes where more people lived in overcrowded housing units. See "COVID-19 Cases in New York City, a Neighborhood-Level Analysis", Furman Center Blog, April 10 2020.

6 Jason Richwine, Steven A. Camarota, and Karen Zeigler, “Household Overcrowding Facilitates the Spread of Covid-19”, Center for Immigration Studies blog, DATE.

7 See Conor Dougherty, "12 People in a 3-Bedroom House, Then the Virus Entered the Equation", The New York Times, August 1, 2020, and Ben Poston, Tony Barboza, and Ryan Menezes, "L.A.'s most crowded neighborhoods fear outbreaks: 'If one of us gets it, we are all going to get it'", The Los Angeles Times, April 22, 2020.

8 Michelle A. Waltenburg, et al., “Update: COVID-19 Among Workers in Meat and Poultry Processing Facilities — United States, April–May 2020”, Morbidity and Mortality Weekly Report, July 10, 2020.

9 Hourly wage figures only include employed workers for whom earnings were reported. In some cases, earnings in public-use Census Bureau data are implausible. Following the example of other researchers, we report hourly wages for individuals earning $1.01 to $202.58 an hour. Hourly wages are calculated by taking reported annual earnings and dividing that by the number of weeks worked in a year and the usual hours worked per week, both of which are reported in the survey. The “weeks worked last year” variable is only reported as intervals (e.g. 14-26 weeks) so we assign the mid-point of the interval to each respondent. Researchers at the Center on Wage and Employment Dynamics at the University of California, Berkeley, and researchers at the Brookings Institution follow this same basic approach when using the ACS. The Economic Policy Institute was the first to employ this approach. Our upper- and lower-wage bounds reflect their figures for 1989 adjusted to reflect inflation.

10 There are actually 23 broad occupational categories; however, we report figures for 24 because we have separated construction jobs from extraction jobs. These two categories are distinct and have very different immigrant shares.

11 Table A1 in the appendix reports the codes from the ACS for each broad job category and each specific occupation. In a few cases, we have combined occupations to obtain larger sample sizes and more robust statistical estimates.

12 The regions in this report are defined in the following manner: Countries that can be identified in the public-use 2018 ACS file are coded as the following regions: Mexico; Central America: Belize, Costa Rica, El Salvador, Guatemala, Honduras, Nicaragua, and Panama; South America: Argentina, Bolivia, Brazil, Chile, Colombia, Ecuador, Guyana, Paraguay, Peru, Uruguay, Venezuela, and South America not specified; Caribbean: Bermuda, Cuba, Dominican Republic, Haiti, Jamaica, Antigua-Barbuda, Bahamas, Barbados, Dominica, Grenada, St. Lucia, St. Kitts-Nevis, St. Vincent, Trinidad and Tobago, and Caribbean and West Indies and Americas not specified; South Asia: India, Bangladesh, Pakistan, Sri Lanka, Bhutan, and Nepal; East/Southeast Asia: China, Hong Kong, Taiwan, Japan, Korea, Cambodia, Indonesia, Laos, Malaysia, Philippines, Singapore, Thailand, Vietnam, Burma, Mongolia, Asia not specified; Europe: Denmark, Finland, Iceland, Norway, Sweden, England, Scotland, United Kingdom, Northern Ireland, Ireland, Belgium, France, Netherlands, Switzerland, Albania, Greece, Macedonia, Italy, Portugal, Azores, Spain, Austria, Bulgaria, Czechoslovakia, Slovakia, Czech Republic, Germany, Hungary, Poland, Romania, Yugoslavia, Croatia, Bosnia, Serbia, Kosovo, Belarus, Montenegro, Cyprus, Latvia, Lithuania, Byelorussia, Moldova, Ukraine, Armenia, Georgia, Russia, USSR not specified, and Europe not specified; Middle East: Afghanistan, Azerbaijan, Kazakhstan, Kyrgyzstan, Uzbekistan, Iran, Iraq, Israel/Palestine, Jordan, Kuwait, Lebanon, Saudi Arabia, Tunisia, United Arab Emirates, Syria, Turkey, Yemen, Algeria, Egypt, Morocco, Libya, Sudan, and North Africa not specified; Sub-Saharan Africa: Cape Verde, Ghana, Guinea, Liberia, Nigeria, Senegal, Sierra Leone, Ethiopia, Kenya, Somalia, Tanzania, Uganda, Zimbabwe, Eritrea, Cameroon, South Africa, Zaire, Congo, Zambia, Togo, Gambia, Rwanda, Ivory Coast, South Sudan, and Africa and Western and Eastern Africa not specified; Canada; Oceania/Elsewhere: Australia, New Zealand, Fiji, Tonga, Marshall Islands, Micronesia, American Samoa and Elsewhere. (Starting in 2018 the Census Bureau no longer automatically classifies those born in America Samoa as American citizens, as was the case in prior years. They can now be foreign-born. When persons from this territory indicate on the citizenship question that they were not citizens at birth, we include them with those born in Oceania or elsewhere.)

13 Larger counties are defined as those with a total population of at least 50,000 residents and come from the five-year (2014-2018) American Community Survey generated at data.census.gov. It is not possible to use public-use 2018 ACS data for a county-by-county analysis as many of the counties are not identified in the data. Therefore, it is necessary to use county data generated at data.census.gov. Data.census.gov does not allow for crowding statistics to be calculated for workers. So our analysis is based on all persons. There are 975 counties with populations over 50,000 and they account for nearly nine out of 10 of U.S. residents. Confining the analysis to these counties makes sense because the sample size in smaller counties is quite modest. Moreover, characteristics like overcrowding or the immigrant share of the population tend to be uncommon in many small counties, so any estimate is based on a tiny subset of an already small sample.

14 As is the case in Figure 7, the foreign-born share at the county level is based on the 2014 to 2018 American Community Survey from data.census.gov. The Covid-19 infection rate at the county level is based on the New York Times Covid-19 online database, as of September 1, 2020.

15 It makes less sense to compare average wages in the broad job categories because they include many very different specific occupations, some of which are relatively high paying and others relatively low paying. For example, doctors and licensed practical nurses are both in the healthcare professions broad job category, but they earn very different wages. Table A1 does provide hourly wages for the broad occupational categories.

16 The figures are similar in other recent years.

17 It is also the case that 63 percent of immigrant workers live in a PUMA that has a population density greater than 3,000 people per square mile, compared to 31 percent of native-born workers.

18 For the continental United States in 2018, the poverty threshold for a family of three was $20,780 and it was $25,100 for a family of four. Families, individuals, or, in the case of our analysis, workers, living below these thresholds are considered to be in poverty. Families are similar to households, but the two are not synonymous. A family is typically a group of two or more related people living together. Households are any group of individuals living in the same housing unit.

19 It is possible to calculate what share of immigrant workers would be in overcrowded conditions if the share in poverty or near poverty was the same as it is for natives. In 2018, 8 percent of immigrant workers lived in poverty and 19.2 percent lived in near poverty, as we define it. For native workers, 5.5 percent lived in poverty and 12 percent lived in near poverty. The remainder of the population can be thought of as at least lower-middle-class. The overcrowding rate for those not in or near poverty is 10.5 percent for immigrant workers and 2.5 percent for natives. If the share of immigrants in or near poverty was the same as it is natives, but they retained their overcrowding rates by poverty status, then 12.9 percent of immigrant workers would be in crowded housing. This is not very different than the 14.3 percent who are actually in crowded households. Clearly, the larger share of immigrants in or near poverty does not explain their much higher rates of overcrowding relative to natives. Rather, it is their high rates of overcrowding regardless of poverty status that accounts for almost all of the differences with natives.

20 In 2018, immigrant workers in or near poverty, as we define it, accounted for 46.6 percent of those in overcrowded conditions. Among native-born workers, those in or near poverty accounted for 41.8 percent of those in overcrowded conditions.

21 One way to think about the difference is that in the New York MSA (Table A7, Scenario F), in the 42 comparisons that are possible by wage and household size, the average difference between immigrants and natives is 12.4 percentage points. Looking at New York City only, 40 comparisons are possible that control for wage and household size, and the average difference is 9.4 percentage points. So most of the difference persists even when we focus on just the city itself.

22 In the 42 comparisons possible in the Los Angles MSA (Table A7, Scenario H) that control for wages and household size, the share of immigrant workers living in overcrowded housing averages 9.8 percentage points higher than that of the native-born. In the 40 comparisons possible for Los Angeles County only (Table A7, Scenario I), immigrant overcrowding averages 9.2 percentage points higher than that of native-born workers. And in the 40 comparisons possible for the most densely populated parts of Los Angeles County (Table A7, Scenario J), immigrant overcrowding averages nine percentage points higher than that of native-born workers.

23 Our prior analysis indicates that immigrants are coming to America at older ages. In 2017, the average age at arrival for new immigrants was 31 or 32 years, depending on how recent arrival is defined.

24 The seemingly high average household incomes for the households where workers in overcrowded conditions live is worth commenting on. The household income figures in Table A9 are by workers, not by households. This means that households with more than one worker will be counted more than once and averaged together. Nonetheless, the average household income would still be $81,244 for all overcrowded households, if measured by household rather than by worker. This is less than $98,031 shown at the top of Table A9 for all workers, but still relatively high. The key point is that overcrowded households are relatively large. In the case of immigrant workers, Table A9 shows the average income is $94,000 and for native workers, it is $101,00. Again, these values may seem surprisingly high. It must be remembered that in both cases these households have nearly three workers on average. So the average income figure reflects this fact. Each worker is still making a relatively modest wage as the hourly wage data indicates. Also note that all of the household income figures shown in the table are averages, not a median figure, which would be lower.

25 These include spouses of native-born citizens; veterans; people who have government jobs; Cubans (because of special rules for that country); immigrants who arrived before 1980 (because the 1986 amnesty should have already covered them); people in certain occupations requiring licensing, screening, or a government background check (e.g., doctors, pharmacists, and law enforcement); and people likely to be on student visas.

26 CIS has previously used the Department of Homeland Security (DHS) as the source of those known characteristics; however, DHS data were last published in 2015.

27 “State-Level Unauthorized Population and Eligible-to-Naturalize Estimates”, Center for Migration Studies, undated.

28 In 2018, CMS estimated a total illegal immigrant population of 10.6 million, which includes an undercount adjustment for those missed in Census Bureau data. Our analysis totals to 9.8 million illegal immigrants in the ACS without an undercount adjustment.

29 The bottom of Table A2 reports population shares by occupation and legal status. It shows that legal immigrants comprise an estimated 13.4 percent of all workers while illegal immigrants account for 4 percent of all workers.

30 World bank remittance estimates can be found here.

31 In 2008, the Census Bureau reported that 27 percent of immigrant households sent remittances and these households account for 90 percent of all money sent abroad from the United States.