National Review, April 13, 2023

Numerous commentators have argued that there is a shortage of immigrant workers because of the slowdown in new arrivals during the pandemic. The Associated Press asserts that immigration to the U.S. after the Covid outbreak “ground to a near complete halt.” For CBS News, immigration “hit a brick wall” during that period. “America doesn’t have enough immigrants” to fill jobs, according to CNN.

The falloff in immigration caused by the pandemic was short-lived, however, and it is the native-born — not immigrants — who are absent from the labor force. Partly as a result of the ongoing border crisis, the number of foreign-born workers has rebounded spectacularly since the end of 2020 and is now well above pre-pandemic levels. To the extent that there might be a worker shortage, the cause is the troubling decades-long decline in the labor-force-participation rate of the U.S.-born population.

The foreign-born population in the U.S. includes naturalized citizens, permanent residents, temporary visitors, and illegal aliens. In statutory language, “immigrants” are permanent residents, but most people use the term synonymously with “foreign-born,” and I will do the same here. The legal-immigrant population grew by about 5 million in the decade before the pandemic, while the illegal population remained roughly stable. Yes, hundreds of thousands of illegals cross the border or overstay visas each year, but hundreds of thousands also get deported, leave on their own, or die. Others are legalized, typically through the granting of asylum or marriage to an American citizen.

The total foreign-born population (legal and illegal) fell during the pandemic but exploded after Joe Biden’s election. The government’s household survey shows that, from October 2020 to November 2022, the immigrant population increased by 4.5 million, reaching an all-time high of 48.4 million. Immigrants now constitute a slightly smaller share of the total population — 14.7 percent — than they did in 1890, when the immigrant share of the total population was 14.8 percent. But if the growth of the foreign-born population continues at the current pace, we will blow past that record by this summer. While the delayed processing of Covid-era legal-immigration backlogs accounts partly for this recent surge, my colleague Karen Zeigler and I have estimated that about 60 percent of the increase is due to new illegal immigrants.

|

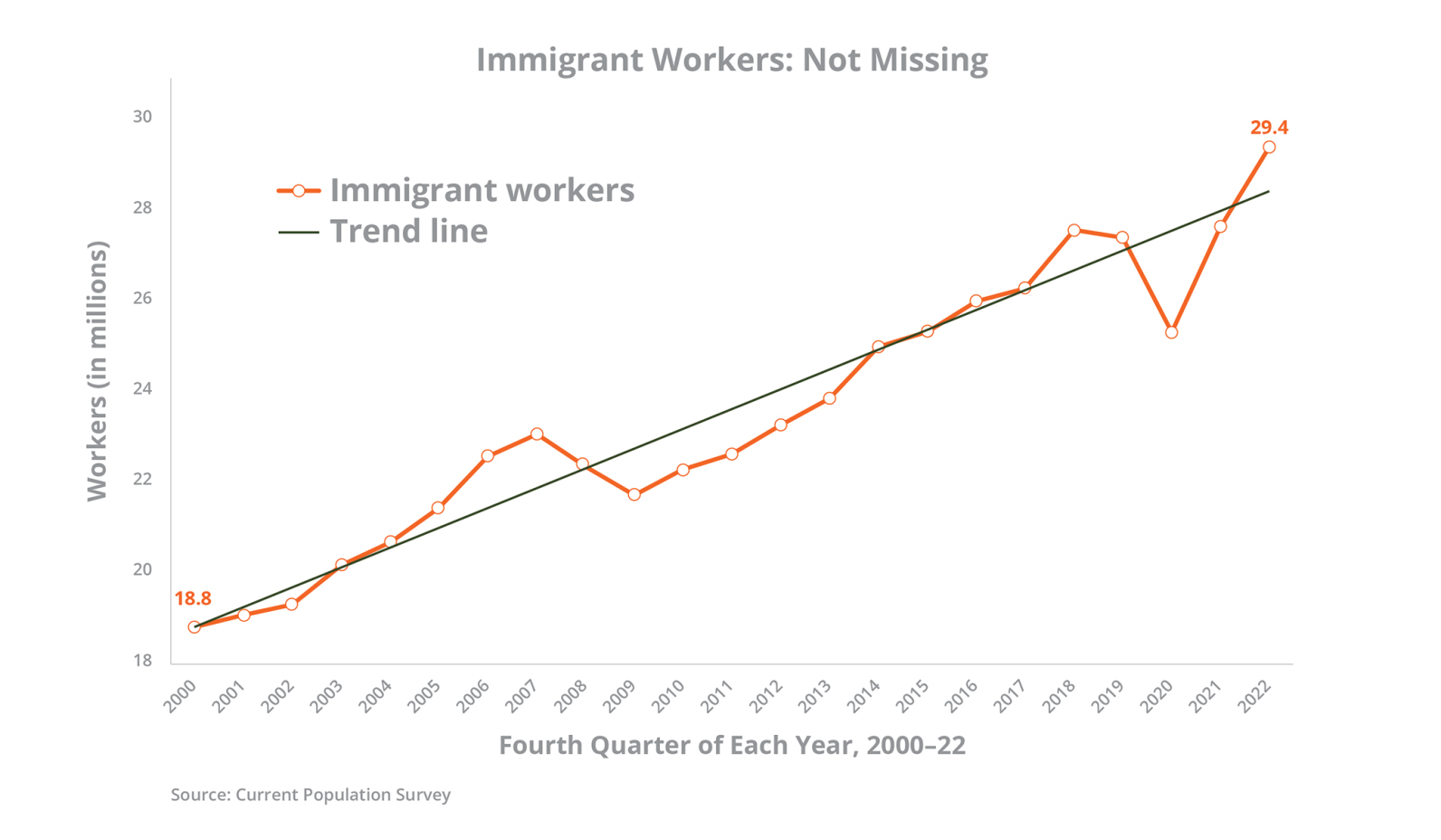

The number of immigrant workers did decline by 2 million from 2019 to 2020, but by the fourth quarter of 2021, it had fully recovered. By the fourth quarter of 2022, there were 2 million more immigrant workers in the U.S. than there had been before the pandemic — well above the long-term trend line. By contrast, there are 2 million fewer U.S.-born workers now than in 2019. Clearly those “missing” from the workforce aren’t the immigrants.

Since immigration has rebounded, why is there so much coverage of a supposed shortfall in immigrant workers? Part of the reason could be the Census Bureau’s estimate that migration was very low through mid 2021. That estimate has since been revised upward. More important, the 2021 estimate is out of date. The bureau’s new estimate (which is almost certainly still too low) shows that immigration through mid 2022 more than doubled compared with the year before.

The missing-immigrants narrative was also boosted by an analysis by UC Davis economists Giovanni Peri and Reem Zaiour, who argue that the pandemic slowdown led to 1.7 million “missing” immigrant workers through June of last year. But their analysis (which is based on older data) focuses on working-age immigrants, not actual workers. Nevertheless, when the media pick up on a talking point that supports their preexisting policy preferences — in this case, their preference for increasing the level of immigration — that talking point tends to persist even in the face of contrary evidence.

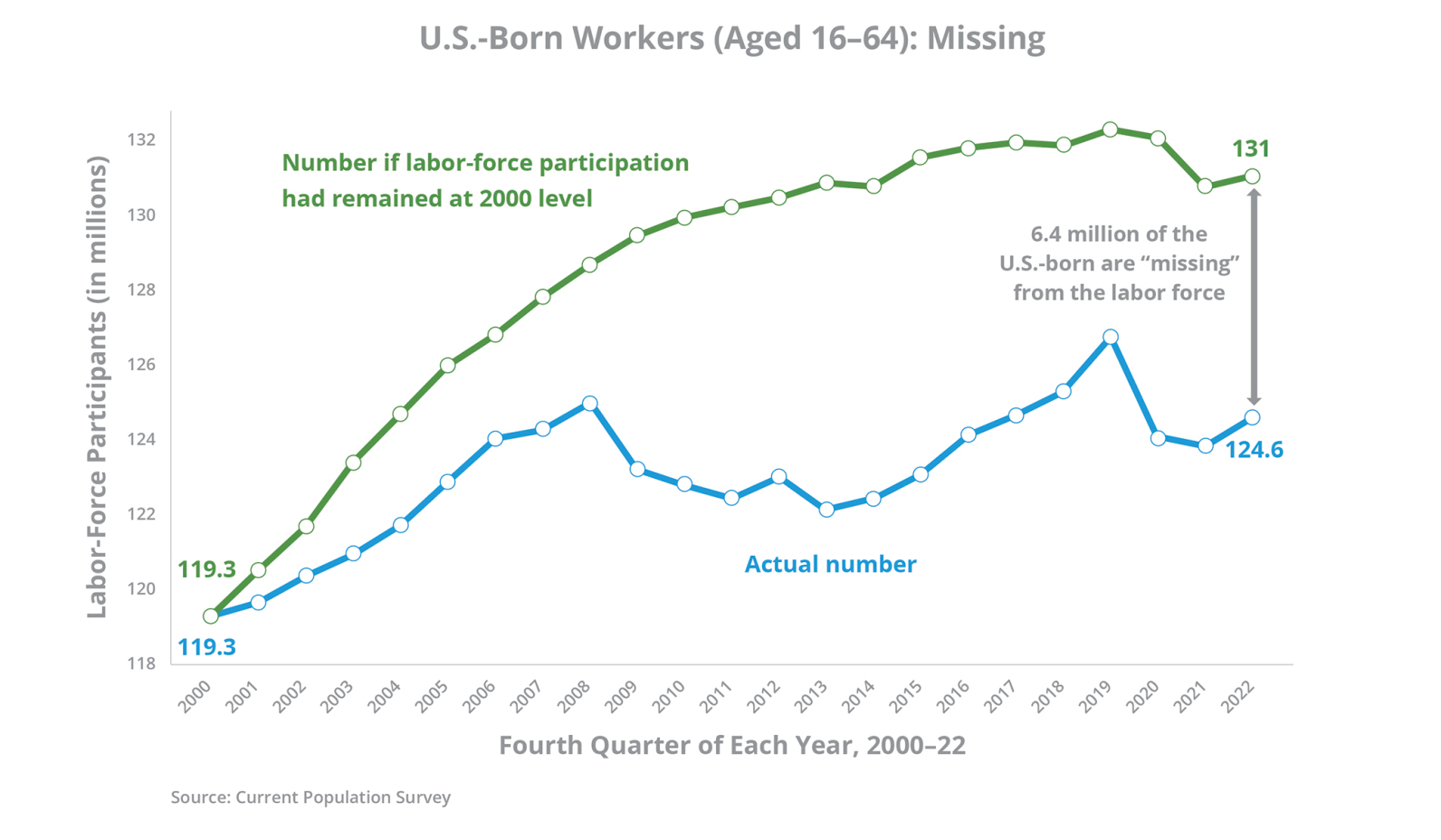

The key problem for the U.S. labor market is not a lack of immigrant workers; rather, it’s that too many working-age natives are sitting on the sidelines. Excluding inmates, the share of working-age U.S.-born men who hold a job, or are at least looking for one, has declined steadily since the 1960s. The labor-force-participation rate of U.S.-born women rose until about the year 2000 and has declined since, even as the share of U.S.-born women with children has also declined significantly. The decline in employment is primarily among the U.S.-born non-college-educated, and this holds true whether one studies the 16-to-64, 18-to-64, or 25-to-54 age range.

|

Recessions tend to accelerate the decline: The labor-force-participation rate recovers somewhat with the economy but never reverts to where it was before the downturn. For example, the labor-force-participation rate for U.S.-born adults aged 18 to 64 without a bachelor’s degree was 70.3 percent in the fourth quarter of 2022, compared with 71.4 percent in 2019 (before the pandemic), 74.8 percent in 2006 (before the Great Recession), and 76.4 percent in 2000 (before the dot-com crash).

We probably can never get back to the labor-force-participation rates for men that we observed in the 1960s or even the 1980s. But if U.S.-born men and women of working age had participated in the labor force in the fourth quarter of 2022 at the same rates at which they did in 2000, there would be an additional 6.4 million workers today.

Although rarely discussed in the context of immigration policy, the decline in the labor-force-participation rate of the native-born is hardly a secret. It has been studied extensively, for example, by the Obama White House and the Federal Reserve. One of the best books on the subject is Nicholas Eberstadt’s Men without Work.

One reason why all the potential workers on the economic sidelines are often ignored in the public discourse is that many observers are distracted by deceptively low unemployment rates. But these statistics include only those who report that they have sought work in recent months. They do not include the roughly 54 million working-age people who are neither working nor looking for work.

The explanations for the decline in labor-force participation are as varied as the proposed solutions. Some blame the easily accessible welfare and disability systems. Others emphasize the large number of less educated men with criminal records, who have an especially difficult time finding willing employers. Some believe that structural changes in the economy — particularly the declining wages of the non-college-educated — are the real problem. Eberstadt emphasizes changes in the expectations and values related to work, including a decline in institutions that encourage it, particularly the family.

Competition with immigrants has also played a role in reducing the labor-force participation of natives. One large 2016 study by the National Academies of Sciences, Engineering, and Medicine concluded that immigration reduces wages for some U.S.-born workers, mainly the less educated, which reduces the incentive to work. An analysis of Equal Employment Opportunity Commission discrimination cases by my colleague Jason Richwine found that employers tend to favor foreign-born over native-born workers for manual-labor jobs. More specifically, there is research showing that immigrants displace high-school-age Americans from the labor force. More than one recent academic paper finds a geographic crowd-out effect: Immigrants tend to move into economically dynamic areas, reducing the incentive for natives to relocate there. Of course, not every job taken by an immigrant is one lost by a native, but allowing in millions of immigrant workers has consequences.

Some may think that immigrants take only the jobs that Americans don’t want, but the U.S.-born make up the majority of workers in all but six of the 474 government-defined occupational categories. Even in the 20 occupations with the highest shares of immigrants, there are still 3.5 million U.S.-born workers. The idea that immigrants and natives never compete is simply untrue. It is true that most workers in agriculture are immigrants, but they constitute less than 1 percent of the total workforce, and there is already an unlimited guest-worker program to serve the needs of this tiny sector.

Beyond direct job competition between immigrants and natives, there is perhaps a more profound issue: Bringing in so many immigrant workers year after year allows us to simply ignore all the Americans who are out of the labor force and the social and other pathologies that follow their joblessness. After all, why worry about people on the economic sidelines when we can hire eager immigrants instead?

Those pathologies include higher levels of substance abuse, welfare dependency, mental-health problems, obesity, crime, and failure to form families, as well as lower life expectancy. Of course, these things interact in complex ways, but the evidence is clear that when the able-bodied, particularly men, decline even to look for a job, their families and their communities suffer alongside them. We can either figure out how to get more Americans back into the labor force or continue to allow large numbers of foreign workers to meet our labor needs and then try to apply Band-Aids to worsening social problems.

To be sure, encouraging and helping less educated Americans to find jobs will not be easy. It will require difficult reforms of our welfare and disability systems. We will have to deal with the opioid and mental-health crises. Improving job training and even re-examining trade policies must be part of the solution. Probably the most challenging but necessary task will be to re-instill in these individuals an appreciation of the value of work and self-sufficiency. Allowing wages to rise for the less educated, partly by reducing immigration, would certainly help.

It may be tempting to throw up our hands and say, “Forget lazy Americans, let’s just bring in immigrants who will work.” But the higher costs of welfare, disability, law enforcement, and health care associated with low labor-force participation are paid by taxpayers. Moreover, the crime and social dysfunction that are so common among men who do not work affect everyone around them, and as more kids grow up in households where work is not the norm, the problem is likely to get worse.

Perhaps the most important reason we should care about those who remain out of the labor force is that they are our fellow Americans, even if some of them have made bad choices. Most immigrants, even illegal immigrants, are decent people who come to America for the same reasons people have always come: They are simply looking for a better life. But our fellow Americans, particularly those who are struggling, should have a much greater claim on us than prospective immigrants. Immigration is much more than a way for employers to hire new workers, and the current level has serious implications for everything from schools to the health-care system to physical infrastructure to culture. To allow more immigration simply as a way to address a labor-force shortage is to turn a blind eye to the destructive impact of idleness among our fellow citizens.