When Michael McLaughlin applied to be a driver for Helados La Tapatia, a frozen-dessert producer in California, the hiring manager allegedly warned him that the company rarely hires non-Hispanics. The manager “had to pull a lot strings” to get McLaughlin on board, but the employment didn’t last. Despite a spotless training record, McLaughlin was quickly fired by the company’s president for not speaking Spanish. There was no indication that Spanish was necessary to perform his job, but the company allegedly used the language requirement as a means to avoid non-Hispanics.

McLaughlin was one of several non-Hispanic whites and blacks who were named plaintiffs in a case brought against Helados La Tapatia by the Equal Employment Opportunity Commission (EEOC). The EEOC alleged that among the company’s 475 hires over a four-year period, only 12 were white, and just two were black. In response to the EEOC lawsuit, the company recently agreed to pay a $200,000 fine, compensate the plaintiffs, and change its hiring practices.

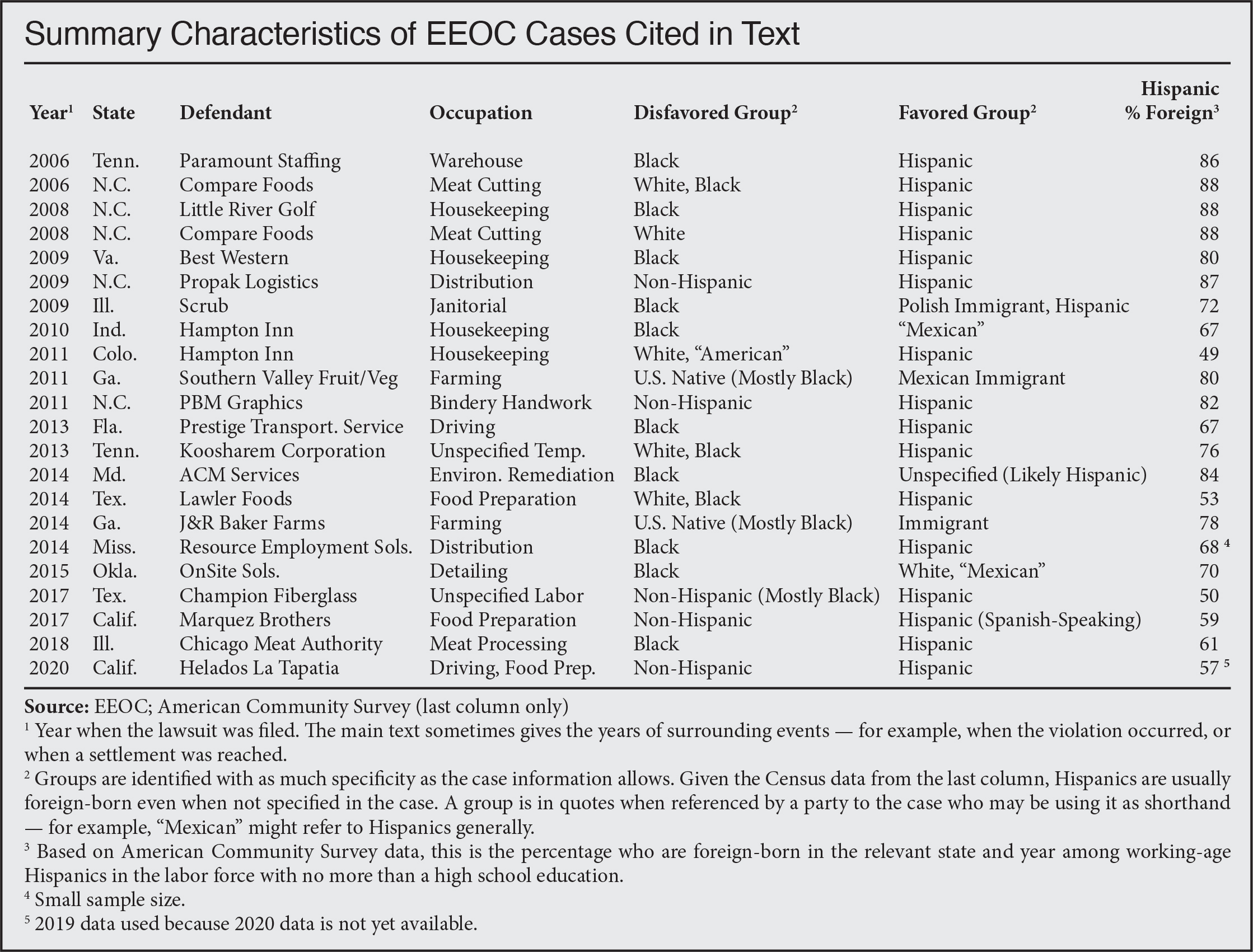

The lawsuit against Helados La Tapatia is the latest in a long string of immigrant- or Hispanic-preference EEOC cases that I documented in a 2019 CIS report, entitled “No Americans Need Apply: EEOC lawsuits reveal how employers are eager to replace low-skill native workers with immigrants”. Although this most recent case was not about favoring immigrants per se, one can infer that immigrants received an advantage, given that 57 percent of California’s working-class Hispanics are foreign-born. In other EEOC cases, the anti-native bias is more explicit. Here is an excerpt from the CIS report:

Southern Valley Fruit and Vegetable, located in Georgia, favors foreign-born labor. According to a 2011 EEOC lawsuit, Southern Valley primarily employs Mexicans for the harvest season, but would (initially) hire Americans as well. Shortly after each harvest began, most of the Americans would be summarily discharged. “All you Americans are fired,” one manager told a group of 80 who were let go at the same time.

On another day that at least 16 Americans were fired, a manager stated, “All you black American people, fuck you all. ... [J]ust go to the office and pick up your check.” In an accompanying press release, the district director in the EEOC's Atlanta office claimed that “the practices alleged in the lawsuit are relatively common in the industry.” An attorney with Georgia Legal Services added, “Discrimination against American workers in the H-2A guestworker program is endemic. We hope this case will bring attention to that problem.”

As the passage suggests, the Americans who are disfavored for low-skill work are most often black. Another example:

When a warehouse in Memphis, Tenn., began using a new employment agency called Paramount Staffing to fill its daily work crew, Paramount “essentially replaced the African Americans with Hispanics,” according to the EEOC. Potential workers would line up outside the warehouse each day, but Paramount would select Hispanics over blacks, even when black workers were experienced and farther ahead in line. Sometimes Paramount's managers would send potential black workers home by announcing in English that there were no more positions. “After the African Americans left, the Hispanics were allowed to come into the warehouse and work.”

Why do these anecdotes matter? Because the patterns of employer behavior on display here are consistent with the claim that immigration hurts the labor-market prospects of low-skill native workers. In combing through the EEOC’s casework, it’s clear that hiring bias is not random. One can easily discern a pattern in which employers of low-skill labor prefer to hire immigrants (particularly Hispanics) over natives (particularly blacks). In fact, when Hispanics are the plaintiffs in EEOC cases, it is rarely because they were denied employment or replaced as workers by another group. Instead, Hispanics file claims about working conditions, such as low pay and harassment. The implication is that employers use immigration to maintain an easily controlled and replaceable workforce.

Surveying these EEOC cases helps to supplement econometric work with the kind of tangible, on-the-ground evidence that can often seem more compelling than empirical models. It also shows that immigration advocates who claim “zero” negative impacts on the labor market are out of touch with reality.

The CIS report contained a summary table of each EEOC case it profiled. Here is an updated version that includes the lawsuit against Helados La Tapatia:

|