Download a PDF of this Backgrounder.

Steven A. Camarota is the director of research at the Center.

Summary

This analysis measures the socio-economic status (SES) of U.S.-born adult (ages 25 to 29) children of immigrants (second-generation Americans). We focus on this age group because by this age individuals have traditionally become independent of their parents, but are still young enough that their immigrant parents are relatively recent arrivals. We find that the SES of these younger second-generation adults nearly equals that of third-generation-plus Americans (those with U.S.-born parents) in most but not all measures of SES. However, this overall picture obscures the situation for second-generation Hispanics — who comprise more than half of all children born to immigrants in recent decades, and who have much lower SES than second-generation Americans generally. In fact, even third-generation Hispanics have a SES that is a good deal lower than for third-generation Americans overall. Though they lag behind third-generation Americans, second-generation Hispanics are still much better off than were their immigrant parents. It also bears mentioning that second-generation Americans 25 to 29 examined in this analysis are not the children of today’s immigrants. On average, we estimate that the parents of even these relatively younger adults arrived four decades ago. The children born to immigrants who arrived in the last 30 years are too young to measure their SES separately from their parents.

Introduction

We do not know how children born to immigrants today will fare once they reach adulthood, as they are still too young to measure their socio-economic status (SES) as independent adults.1 Economic and social conditions in the United States are constantly changing and the dramatic growth in the immigrant population over the past several decades means that immigrants are arriving into a very different country than immigrants in prior periods of American history, to say nothing of the how the immigrants themselves may have changed.2

Although we cannot know how the children of today’s immigrants will do in the future, we can still look at how children born to immigrants in the past have fared. This may provide some insight into how well the children born to immigrants today may do as adults. This report focuses on the youngest group of the second generation possible, those who, for the most part, are old enough to be independent of their parents — 25 to 29-year-olds — but young enough that their parents are still relatively recent arrivals. We use the terms “immigrant” and “foreign-born” interchangeability in this analysis to mean all those who were not U.S. citizens at birth, including naturalized citizens, legal permanent residents, and illegal immigrants, all of whom are captured in Census Bureau data. We define the second generation as anyone with a foreign-born mother or father and the third generation as anyone with two U.S.-born parents.

When thinking about the economic assimilation of the children of immigrants, it is also important to remember that a significant share of immigrants arrive in America well educated or specifically came to America in order to earn a bachelor’s or graduate degree. Tables 1 and 2 report the education level and average income from all sources for immigrants and the native-born in 1990 and 2019. The tables show enormous differences between sending countries and regions in education and income. The offspring of well-educated immigrants do reasonability well, but it may not be entirely accurate to describe prosperous parents having relatively prosperous children as successful assimilation. Rather, it may simply reflect the advantages that well-educated, higher-income parents commonly transfer to their children in all countries — regardless of parental nativity.

Methods and Data

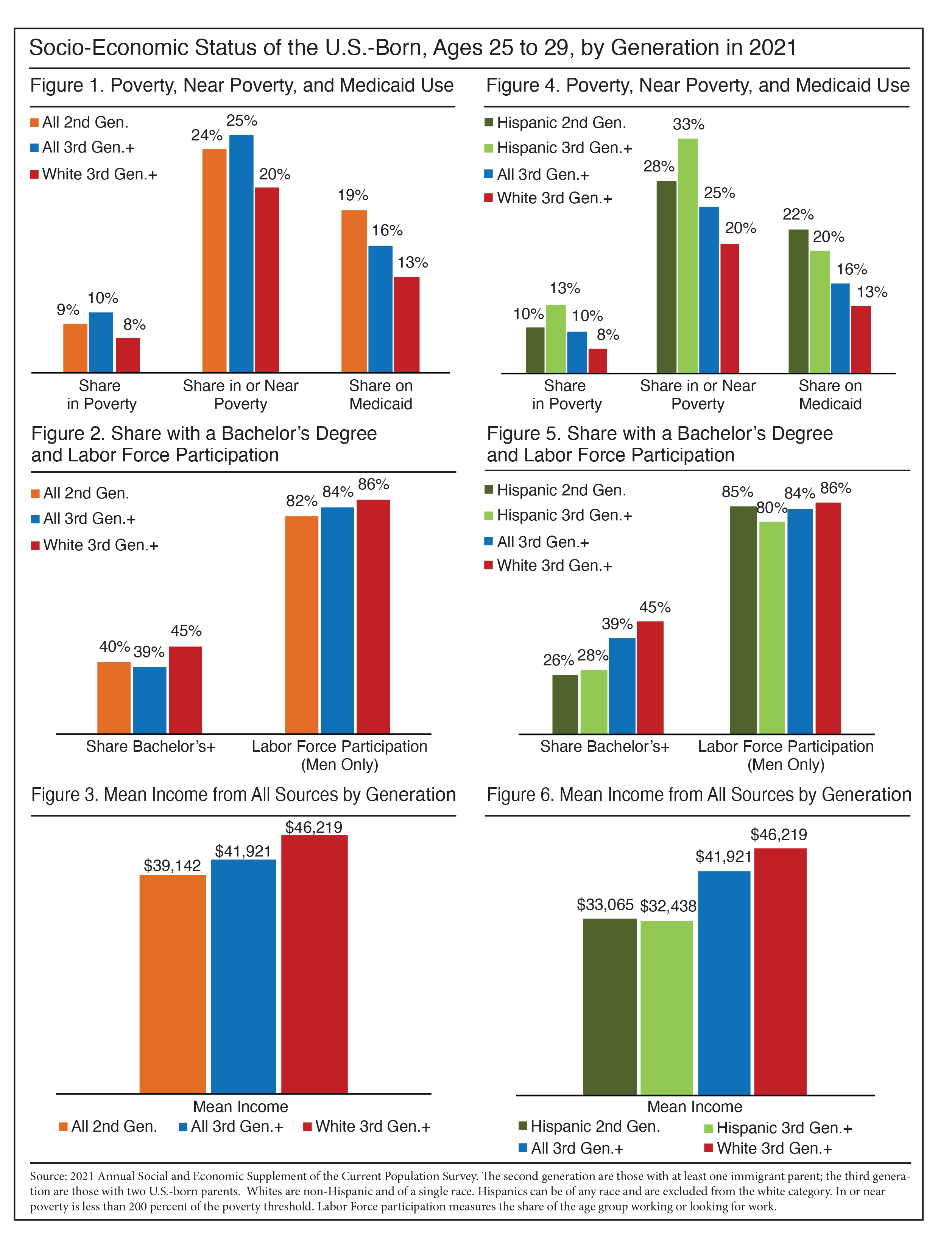

Measures of Social Economic Status. Figures 1 through 6 summarize many of our results on the socio-economic status of 25- to 29-year-olds by generation. (Table 3 reports more detailed information, including breakdowns by gender.) All of the numbers in the figures and table are based on our analysis of the Annual Social and Economic Supplement to the Current Population Survey (ASEC CPS) collected in March 2021 by the U.S. Census Bureau.3 The survey is one of the only large government surveys that asks respondents about their citizenship and parents’ place of birth, making it possible to identify the foreign-born (immigrants), the second generation, and all those in the third generation and beyond. For simplicity, throughout the remainder of this Backgrounder we use the term “third generation” to mean all those with two U.S.-born parents, which includes the third generation, but also the fourth generation and beyond.

Target Population of Second-Generation Americans. We examine individuals 25 to 29 because by this age people are unambiguously adults, and typically have completed a bachelor’s degree, if they went to college. They also are typically in the labor market (working or looking for work) and traditionally are independent of their parents. We also focus on this age cohort because they are young enough that their immigrant parents are still relatively recent arrivals. Looking at the children of more recent immigrants should be more relevant to the current debate over immigration. If we examined second-generation, U.S.-born Americans in older age groups, then their parents would have arrived correspondingly even further back in time.

Parental Year of Entry. Even though these second-generation Americans 25 to 29 are relatively young, their parents are still not that recently arrived. We estimate that, in 2021 a little less than a third of the parents of our target population of second-generation Americans arrived in 1979 or earlier, about half arrived in the 1980s, and about one-fifth arrived 1990-1996. The estimated mean year of arrival in the United States for these immigrant parents is 1983.4 Even though the second-generation Americans we focus on here are only in the latter half of their 20s, their parents still arrived about four decades ago on average.

SES of Immigrant Parents. In the early 1990s, 45 percent of the immigrant parents of our target population of second-generation adults 25 to 29 had not completed high school and 19 percent had at least a bachelor’s degree. The parents of third-generation Americans 25 to 29 were much more educated at that time, with only 14 percent not having completed high school and 23 percent having at least a bachelor’s degree. The immigrant parents of U.S.-born, second-generation Hispanics tend to be much less educated than immigrant parents overall or third-generation parents — 64 percent of Hispanic immigrant parents had not completed high school and only 6 percent had at least a bachelor’s degree back then. The share of immigrant parents with low incomes — in or near poverty — was also much higher than that of U.S.-born parents. Of the parents of our target second-generation population, 63 percent were in or near poverty (less than 200 percent of the poverty threshold) in 1997 when their children were young. The figure is 77 percent for the immigrant Hispanic parents of the second generation. In contrast, 43 percent of the parents of third-generation Americans 25 to 29 in 2021 were in or near poverty back in 1997.5

The above statistics are only for one point in time. The National Academy of Sciences’ extensive 2017 study of immigration to the United States found that each new wave of immigrants since the 1960s has tended to start out poorer and not speak English well at least through the 1990s. Moreover, the progress they make in the United States over time, while substantial, still leaves them less able to speak English well and poorer than prior waves of immigrants relative to the U.S.-born.6 If a larger share of immigrants struggle with English and earn lower wages at arrival and over time than earlier waves, then this may have important implications for the assimilation of their U.S.-born children. Given the slowing progress of immigrants, it may be premature to assume that the children of more recent immigrants will do as well as immigrants who arrived in generations past.

|

Findings

The Second Generation Compared to the Third. Figures 1 through 6 report the SES of second- and third-generation Americans 25 to 29. Table 3 reports more detailed information, including SES by gender. Turning first to Figure 1, it shows that, relative to the third generation of the same age, the second generation is as likely to be in poverty or in or near poverty as all third-generation Americans. However, relative to third-generation white Americans, the rates of poverty and near poverty for second-generation Americans are somewhat higher.7 In terms of being on Medicaid, Figure 1 shows that the second generation is more likely to use the program relative to the third generation — 19 percent vs. 16 percent.8 There is more difference with third-generation whites, 13 percent of whom are on Medicaid.

Figure 2 shows that the share of the second generation with at least a bachelor’s degree is basically identical to the third generation, though the rates for the second-generation do lag behind third-generation whites somewhat. The labor force participation of men — the share working or looking for work — is somewhat lower for the second generation than for the third, especially relative to third-generation whites, though the differences are not that large. Finally, Figure 3 shows that the second generation overall has lower mean income than the third generation and this is especially true when compared to third-generation whites. But again, the differences are not that large.

In sum, Figures 1 through 3 show that the second generation has similar SES with the third generation in terms of the share that have low income and have at least a bachelor’s degree. Their labor force participation, Medicaid use, and average income lag the third generation somewhat. But overall it is fair to say that the difference between third-generation Americans and second-generation Americans in their late 20s is not very large. This is particularly encouraging when we recall that the immigrant parents of the current group of second-generation Americans 25 to 29 years old were much less likely to have completed high school than the parents of third-generation Americans. They were also much more likely to have low incomes back in the early 1990s when second-generation Americans were very young.

Hispanic Share of Second-Generation Americans. Figures 4 through 6 report the SES of second- and third-generation Hispanics. Examining Hispanics is especially important because they comprise such a large share of immigrants. Of our target population of U.S.-born 25- to 29-year-olds with at least one immigrant parent, 58 percent are Hispanic. Hispanics make up such a large share of the second generation because their parents represent a large share of all immigrants and because Hispanics tend to have higher fertility than other immigrant groups. In addition to their population size, focusing on Hispanics is also important because, as already discussed, they tend to be less educated than other immigrants, both now and in the early 1990s. This raises the possibility that a significant share of their children may struggle in the United States.

Second-Generation Hispanics Have Lower SES. Figures 4 through 6 show that second- and third-generation Hispanics tend to lag third-generation Americans overall and non-Hispanic whites in most measures of SES. This is true for the share with low incomes (but not second-generation poverty), Medicaid dependency, completion of a bachelor’s degree, and mean income. In terms of labor force participation, second-generation Hispanic men have very similar rates of work as the third generation overall. One of the largest differences between second-generation Hispanics and third-generation Americans overall is income. Figure 6 shows that the average income of second-generation Hispanics is only 79 percent of third-generation Americans overall and just 72 percent that of third-generation whites.

Third-Generation Hispanics. Perhaps the most troubling finding in Figures 4 through 6 is the seeming lack of progress between the second and third generation for Hispanics and even indications that the third generation is worse off than the second. This is by no means an unexpected finding, as a number of other researchers have found the same thing.9 However, it should be kept in mind that the third-generation Hispanics in Figures 4 through 6 are not the offspring of the second-generation Hispanics shown in the figures. In fact, many third-generation Hispanics are not the descendants of immigrants at all and are instead either Puerto Ricans, who are all American citizens at birth, or are descendants of long-standing Mexican-American communities in the southwest. Second, even though the third-generation Hispanics shown in the figures are no better off and in some ways are worse off than the second generation, this actually does not mean there is no progress between the second and “true” third generation (those with immigrant grandparents).

As already indicated, the third generation in the figures includes the true third generation and older generations as well. There is research showing progress for Mexican-Americans, who are by far the largest Hispanic group in the United States, between the second and third generation. But, on the other hand, that does not mean the third generation reaches parity with other third-generation Americans.10 Moreover, the extent to which there is progress between the second and the true third generation does not change the fact that Figures 4 through 6 show that third-generation-plus Hispanic-Americans are still more likely to be poor, are less educated, have lower labor force participation, access Medicaid at higher rates, and have lower average incomes than third-generation-plus Americans generally.

Conclusion

We find that, overall, second-generation Americans 25 to 29, whose parents we estimate arrived about four decades ago, are as likely to have completed college or live in or near poverty as third-generation Americans. In terms of Medicaid use, labor force participation, and average income, the second generation still lags behind the third generation, but the differences are not very large. However, the more positive picture of the second generation overall obscures the significantly lower SES of second- and even third-generation Hispanics, who lag significantly behind third-generation Americans overall. That said, second-generation Hispanics, like second-generation Americans generally, are significantly better off than their immigrant parents on average.

Of course, it must always be remembered that even the younger adult second-generation Americans examined here are not the children of today’s immigrants. The children of immigrants who have entered in the last 30 years are too young for us to measure their SES independent of their parents. Economic opportunities in the United States are continually changing and the children of immigrants are growing up in a country with a dramatically larger immigrant population than was true in the recent past. It is simply unknown how changing conditions in this country will help or hinder the successful economic integration of immigrants entering today or their U.S.-born children once they reach adulthood.

End Notes

1 As a general rule, the U.S.-born children of immigrants have parents who arrived in America roughly 10 years prior to their birth. So, for example, a second-generation American who is 40 years old today typically has parents who arrived roughly 50 years ago. This is only a generalization and it should be obvious that some immigrants have children almost immediately upon arrival, while in some cases immigrants have their children decades after first coming to the United States, particularly those who themselves arrived as children.

2 It may be a mistake to assume, for example, that an immigrant (and subsequently their U.S.-born children) arriving today with only a high school education will do about as well an immigrant who arrived 40 years ago from the same country with the same education. Opportunities in the U.S. economy may have changed in the intervening years for immigrants by education level. In fact, as a recent CIS analysis shows, the value of foreign degrees varies considerably in the modern American economy.

3 We also examined the 2019 ASEC CPS, collected before Covid-19 hit, but the results were similar to the 2021 data. We use the 2021 ASEC CPS because it is the newest version of the data available.

4 We roughly estimate the year of arrival of the parents of these second-generation Americans by using the 1997 ASEC CPS. We look at second-generation children ages 1 to 5 in the 1997 data and use responses to the year-of-entry question of the household head to determine when the parent(s) arrived. The primary limitation of this approach is that not all children in a household are the offspring of the household head, though our analysis finds that the vast majority are. While most second-generation children do live in households headed by immigrants, a modest share do not. Typically, this is because only one of their parents is foreign-born. Finally, it must be remembered that the ASEC CPS groups year-of-arrival data into multi-year entering cohorts in the public-use data in order to preserve anonymity. This makes precisely estimating the mean year of arrival impossible. These limitations aside, it is still the case that we can obtain reasonable estimates of when the parents of second-generation Americans ages 25 to 29 arrived in the United States.

5 We use the same 1997 ASEC CPS data to estimate parental education and the share with low incomes as we used to estimate year of arrival (see end note 4). Like our year of parental arrival, we use the characteristics of household heads who have children ages 1 to 5 in 1997. The shares in or near poverty in the early 1990s may seem high relative to our target population of 25- to 29-year-olds, but it must be remembered that the economy was recovering from a recession back then and poverty or near-poverty reflects both income and family size. As a result, families with children always have dramatically higher rates of poverty or near-poverty than those without children. In contrast, most 25- to 29-year-olds do not yet have children and the share in or near poverty reflects this fact.

6 National Academies of Sciences, Engineering, and Medicine, The Economic and Fiscal Consequences of Immigration, The National Academies Press: Washington, D.C., 2017. Chapter 3 of the report discusses the slowdown in immigrant progress.

7 In or near poverty, which is defined here as less than 200 percent of the poverty threshold, is an important measure of socio-economic status as those with income above this level can be seen as part of the “middle class”. Below this income level, families or individuals begin to be eligible for welfare programs, and do not generally pay federal income tax.

8 Medicaid is an individual-level welfare program, making it an ideal measure for the individual-level analysis done here. In contrast, welfare programs like food stamps or public housing provide subsidies to the entire family.

9 Work by Livingston, Kahn, and others has long shown that Mexican-Americans, even in the third generation, lag behind other third-generation Americans. See, for example, Joan R. Kahn, “An American Dream Unfulfilled: The Limited Mobility of Mexican Americans”, Social Science Quarterly, February 2003.

10 Building on work by Duncan et al., an analysis by the Center for Immigration Studies finds that “the grandchildren of Mexican Americans improve upon their second-generation parents' low average education. However, significant deficits remain. Compared to fourth-plus generation white Americans, third-generation Mexican Americans graduate from college less often, score lower on the AFQT, and earn less income.” These findings are further strengthened by the fact that the prior CIS analysis does not depend on ethnic self-identity and so avoids the problem of ethnic attrition — the tendency of some U.S.-born Americans to no longer identify with their ancestral homeland over the generations. Instead, the analysis directly measured the SES of persons with Mexican grandparents. See Jason Richwine, “Grandchildren of Low-Skill Immigrants Have Lagging Education and Earnings”, Center for Immigration Studies, November 2018.