Table of Contents

Executive Summary

One of the most troubling social trends in recent years has been the rapid increase in the number of people without health insurance. According to the Census Bureau, since 1990 the uninsured population has grown by nearly 10 million and stood at 44.3 million—or one-sixth of the total U.S. population in 1998. Both presidential candidates have proposed major new initiatives costing billions of dollars per year to address the problem.

Efforts to explain the problem have generally focused on trends in employment practices, the rising costs of health care insurance, changes in eligibility for government programs, or the demographic characteristics of the uninsured. To date, relatively little effort has been focused on the impact of immigration policy on this problem. This paper examines the composition of persons without health insurance using the latest data available from the Census Bureau. The findings indicate that while other factors have contributed to the problem, immigration has had an enormous impact on the size and growth of the uninsured population in the United States.

Findings

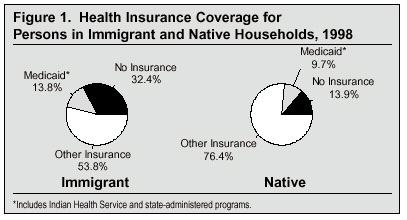

- In 1998, 32.4 percent of persons living in immigrant households (primarily immigrants and their children) lacked health insurance—more than twice the 13.9 percent of persons in native households without insurance.

- Immigrants who arrived between 1994 and 1998 and their children accounted for 59 percent (2.7 million people) of the growth in the size of the uninsured population since 1993.

- The impact of immigration on the overall size of the uninsured population is dramatic. The total uninsured population is one-third larger (32.7 million versus 44.3 million) when the 11.6 million persons in immigrant households without insurance are counted.

- Immigration has made it much more difficult to reduce the size of the uninsured population. For example, in just the last few years immigration has increased the number of uninsured children in the United States by 700,000, enough to offset most of the gains made so far under the State Children’s Health Insurance Program (SCHIP) enacted by Congress in 1997 at a cost of $4 billion a year.

- Although they comprise 13.1 percent of the nation’s total population, persons in immigrant households now account for 26.1 percent of the nation’s uninsured.

- Lack of insurance remains a severe problem even after immigrants have been in the country for many years. In 1998, 37 percent of immigrants who entered in the 1980s still had not acquired health insurance, and 27.2 percent of immigrants who entered in the 1970s remained uninsured.

- The lack of insurance coverage associated with immigrants is primarily explained by their much lower levels of education and their resulting higher poverty rates relative to natives. Because of the limited value of their labor in an economy that increasingly demands educated workers, many immigrants hold jobs that do not offer health insurance and their comparatively low incomes make it very difficult for them to purchase insurance on their own.

- Low levels of education and a high incidence of poverty do not account for all of the difference between immigrant and native households. Even educated and higher income immigrant households are much more likely to be uninsured than similarly situated natives.

- Continued high rates of Medicaid use (Figure 1) among immigrants coupled with low levels of insurance coverage means that almost half (46.2 percent) of persons in immigrant households either have no insurance or have it provided to them at taxpayer expense.

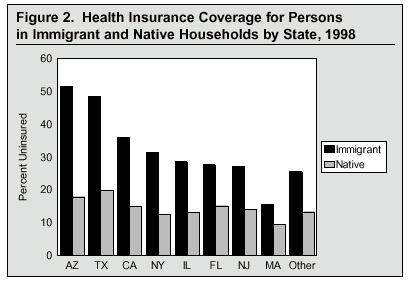

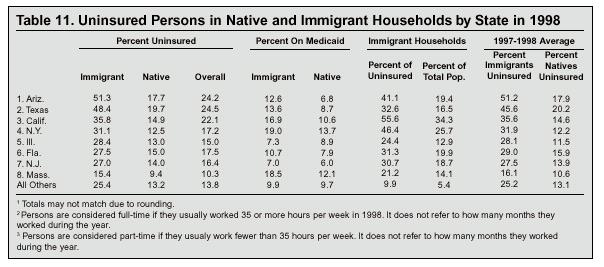

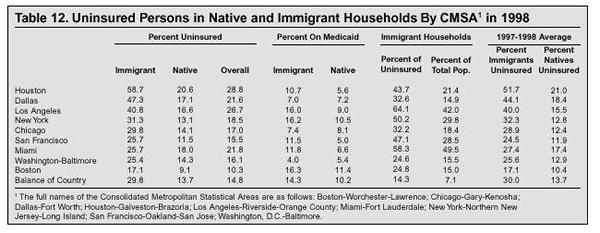

- In every major immigrant-receiving state and metropolitan area in the country, persons in immigrant households are dramatically more likely to be without health insurance than persons in native households (see Figure 2).

- Health insurance coverage varies significantly by country. Households headed by immigrants from Mexico, Central and South America, and Korea are the least likely to have health insurance, while those from Europe, Canada, and the Philippines are the most likely to be insured.

Factors Not Accounting for the Lack of Insurance Coverage Associated with Immigrants

- Although a very high percentage of illegal aliens do not have health insurance, they comprise only an estimated 26.8 percent of the uninsured living in immigrant households.

- The denial of benefits to some legal immigrants enacted as part of the1996 welfare reform legislation is not the reason so many persons in immigrants households do not have health insurance. Before welfare reform was enacted, nearly 31 percent of persons in immigrant households lacked health insurance, very similar to the current rate. Moreover, immigrant households continue to use Medicaid at higher rates than native households.

- The high percentage of persons in immigrant households without insurance is not explained by the presence of humanitarian immigrants (refugees and asylees). Because they have immediate access to the welfare system, including Medicaid, these immigrants and their children are somewhat more likely to have insurance than are other immigrants.

Why Study Immigration’s Impact on the Size of the Uninsured Population?

One may reasonably ask what effect, if any, does a larger national or local uninsured population have, especially for the majority of the population who do have health insurance? In addition to altruism, there are a number of very practical reasons to be concerned about the level of health insurance coverage in America and the role that immigration policy may be playing in this growing problem.

Impact on the Uninsured Already Here

The most obvious reason for concern is that by increasing the size of the uninsured population, immigration makes it much more difficult to help the uninsured already here. A recent study jointly released by the National Academy of Sciences and the Institute of Medicine concluded that the viability of care providers to the uninsured is more at risk today than ever before partly because of the growing size of the uninsured population. The cost of efforts to provide insurance or just basic care to the uninsured is dependent on the number of people in need of such assistance. If immigration increases the number of people who require government-financed health care, then the total cost of such efforts must grow accordingly. This can only reduce political support for such efforts. Alternately, if federal, state, and local outlays for the uninsured remain the same, then the level of services provided to each recipient must be reduced. This, too, is certainly not in the interest of America’s uninsured. Therefore, if one is concerned about the uninsured already here, significantly increasing the size of the uninsured population is certainly counterproductive.

Effect on Taxpayers

Although they do not have insurance, the uninsured still become sick or injured and require medical care. In many cases, the cost of providing medical services to the uninsured is paid by federal, state, and local governments. Many counties and cities that operate public hospitals and/or clinics and which provide services to the uninsured devote a sizable portion of their total budgets to the uninsured. In addition, health care providers are often reimbursed by the federal government for costs incurred treating the uninsured. While no definitive estimate exists for the reimbursement, it is likely that between $15 and $30 billion a year is spent on the uninsured by government at all levels. These costs do not include the more than $150 billion spent annually to provide Medicaid coverage to low-income residents.

Higher Premiums and Costs for Those with Insurance

While governments at all levels do compensate health care providers for some of the care given to the uninsured, a significant share is not compensated. Providers of health care to the uninsured simply cannot absorb all of the costs of providing such charity care, so they pass at least some of the costs along to paying customers in the form of higher prices for treatment, which in turn creates higher insurance premiums for those with insurance. Thus, a growing uninsured population creates a vicious cycle by driving up premiums, thereby reducing the number of employers who can afford to provide insurance. Additionally, higher premiums push the costs of insurance out of reach for many Americans who must purchase coverage on their own.

Increasing the Risk for the Spread of Communicable Diseases

Because they often do not receive routine preventive care and often seek out medical attention only when their condition is more serious, the uninsured unintentionally extend the period of time the public is exposed to communicable diseases. This problem is of particular concern among immigrants, because most come from developing countries where communicable diseases are more common.

Implications for Immigrant and Immigration Policy

Evaluating health insurance coverage among immigrants and their children is important because it is one way of assessing the consequences of immigration policy. It also affords us the best idea of how immigrants admitted in the future are likely to do if current immigration policy remains unchanged. Low rates of coverage imply that a significant proportion of immigrants have not successfully adapted to life in their new country, at least with regard to health insurance. This is important because without a change in immigration policy, the Census Bureau projects that 11 million new immigrants will likely settle permanently in the United States in just the next decade. If current trends continue, immigration may add an additional three to four million people to the ranks of the uninsured over the next 10 years.

In addition to immigration policy, which is concerned with who may come and how many, there is immigrant policy, which deals with how we treat the foreign-born, living in United States. Examining health insurance coverage among immigrants is important because if a large percentage of immigrants and their children already here lack insurance, we must deal with this problem in a constructive manner, whatever immigration policy is adopted in the future.

Methods and Data

Definitions and Data

The data for this study come from the March 1999 Current Population Survey (CPS) collected by the Census Bureau. The 1999 CPS offers the most recent data available and is the source of most official government statistics on the uninsured. Moreover, it is one of the best sources of information on persons born outside of the United States—referred to as foreign-born by the Census Bureau. For the purposes of this report, foreign-born and immigrant are used synonymously.

This report relies on the definition of insurance used in the government’s publication on health insurance, Health Insurance Coverage 1998: Current Population Report P60-208. Persons are considered to have health insurance if they were covered by insurance in the year prior to the survey provided by an employer, a family member’s policy, the government (primarily Medicaid and Medicare), or insurance they purchased themselves. Because the survey was conducted in March of 1999, it measures insurance coverage for 1998.

Methods

This study examines insurance coverage for persons living in immigrant- and native-headed households. Individuals related to the household head by blood, marriage, or adoption, regardless of their own nativity, are considered to be in an immigrant or native household based on whether the household head is foreign-born or native. Individuals who are unrelated to the head are considered immigrant or native based on the nativity of the head of the family in which they reside. For example, a foreign-born husband and wife (one would be the head) with two young U.S.-born children are counted as four people living in an immigrant household. If the same family rents a room to an unrelated native-born woman with a child of her own, then the women and her child would be counted as a separate native household. Individuals who live by themselves or who live with others to whom they are unrelated are in effect their own households and are considered immigrant or native based on their own nativity. Households are defined in this way so that they more accurately reflect the kind of income sharing and insurance eligibility that exists among members of the same family. Using this definition of household, 92.4 percent of the people living in immigrant-headed households were immigrants themselves or the U.S.-born child (under 21) of an immigrant parent. Therefore, this approach primarily measures insurance coverage for immigrants and their children. Because a child’s standard of living, including access to health insurance, is a function of his or her parents’ income, this method captures the full effect of immigration on the size of the uninsured population in the United States.

Policy Implications

The findings in this paper clearly show that immigration policy has significantly increased the size of the uninsured population in the United States. Assuming that policymakers are concerned about this situation, two sets of policy options would seem to merit consideration. The first set of options might involve a new immigration policy that reduces the flow of immigrants who are likely end up among the ranks of the uninsured. This would help to ensure that immigration does not continue to add to the health insurance problem in the future. The second set of policy options would involve the development and implementation of policies that address the needs of uninsured immigrants and their children already here.

Changing Immigration Policy

The lack of insurance coverage among immigrants stems primarily from their low levels of education and high poverty rates. Because of the limited value of their labor in an economy that increasingly demands a highly educated workforce, workers with few years of schooling are the most likely to hold jobs that pay poverty level wages and do not offer health insurance. Given their limited income, less-skilled workers are also often unable to afford coverage when it is not provided by an employer. In 1998, for example, 19 percent of college-educated adults in immigrant households were uninsured, compared to 53 percent of high school dropouts. Therefore, selecting more immigrants based on their skills would increase the percentage of new arrivals in the future who are able to obtain insurance.

Of course, there are benefits from immigration, and these might be enough to offset the costs associated with the dramatic increase in the uninsured population caused by immigration. In 1997, the National Research Council (NRC) examined the economic effects of immigration and concluded that by holding down the wages of the lowest-skilled workers, immigration creates a very small net benefit to the United States. Of course, lowering the wages of the poorest workers may be viewed by many as a cost rather than a benefit. Moreover, the NRC also found that the net drain on public coffers (tax payments minus services used) from immigrant households is enough to offset entirely the small positive economic effects. While opinions over the costs and benefits of immigration differ, the NRC report does make clear that we can curtail immigration without any worry that it will harm the U.S. economy.

Changing Legal Immigration. In most years, 65 to 70 percent of the 700,000 to 900,000 visas awarded are allotted to the family members of U.S. citizens and lawful permanent residents (LPRs). The Commission on Immigration Reform chaired by the late Barbara Jordan suggested limiting family immigration to the spouses, minor children, and parents of citizens and the spouses and minor children of LPRs—eliminating the preferences for the siblings and adult children of citizens and LPRs as well as the visa lottery. The preference for the spouses and children of non-citizens should also probably be eliminated, since these provisions apply to family members acquired after the alien has received a green card, but before he or she has become a citizen. If the parents of citizens were also eliminated as a category, family immigration would be lowered to roughly 200,000 to 300,000 per year. Humanitarian immigration should also undergo some changes. While the system must remain flexible, and in some years may need to expand well beyond the 50,000 originally intended by the Refugee Act of 1980, keeping refugee admissions at around this level would still allow the United States to take in nearly all of the persons identified by the U.N. High Commissioner for Refugees as needing permanent resettlement. The aforementioned changes would significantly reduce the number of legal immigrants admitted each year without regard to their ability to compete in the U.S. economy. Even with these changes, the United States would continue to accept more than twice as many immigrants as any other country.

Reducing Illegal Immigration. While the overwhelming majority of people living in immigrant households without insurance are legal immigrants or are the U.S.-born children of immigrants, reducing illegal immigration would still be helpful in lowering the number of immigrants entering each year who do not have health insurance. Illegal immigration is undoubtedly the lowest-skilled immigration, with an estimated two-thirds having no health insurance. There is broad agreement that cutting illegal immigrants off from jobs offers the best hope of reducing illegal immigration. Doing so requires three steps: First, a national computerized system needs to be implemented that allows employers to quickly verify that persons are legally entitled to work in the United States. Second, Congress needs to provide more funding so the Immigration and Nationalization Service (INS) can increase worksite enforcement efforts. Third, despite recent increases in funding, more could be done at the border. Controlling the border with Mexico would require perhaps 20,000 agents and the development of a system of formidable fences and other barriers.

The cuts in legal immigration proposed earlier would also help reduce illegal immigration because there are approximately four million people waiting their turn to receive the limited number of visas available each year in the various family categories. Such a system encourages people to simply come to the United States and settle illegally in anticipation of the day their visa is issued. Eliminating the sibling and adult children categories would do away with the huge waiting lists. In the long run, cutting legal immigration would also be very helpful in controlling illegal immigration because recent legal immigrants serve as magnets for illegal immigrants, providing housing, jobs, and entree to America.

Increasing Insurance Coverage Among Immigrants Already in the Country

While lowering the number of less-skilled legal and illegal immigrants entering each year would ensure that fewer immigrants admitted in the future end up among the ranks of the uninsured, it would not immediately increase the rate of insurance coverage among immigrants and their children currently residing in the United States. The most direct and simplest way to provide health insurance to persons in immigrant households would be for the government to provide it. Of course, the primary disadvantage of this approach is the cost. Health coverage for the more than 30 million recipients of Medicaid currently amounts to more than $150 billion a year. Providing coverage to the 11.6 million uninsured in immigrant households, or even only the 7.4 million who live in or near poverty, to say nothing of the poor in native households, would cost billions of dollars a year.

Even if providing coverage to all of the uninsured with low-incomes, including those in immigrant households, is thought to be prohibitively expensive, more can be done to increase their rate of insurance coverage. As we have seen, most persons without health insurance live in households where at least one person works. Thus, one set of options that could be pursued would involve changing regulations and tax policy with the intent of making it less expensive for businesses to provide insurance. In addition, both candidates for president have proposed tax credits for the working poor and near-poor so that they can more easily purchase private health insurance if it is not provided by an employer. So as to contain costs, efforts to provide insurance or tax credits could be specifically targeted at subgroups of the uninsured, such as children or those with the lowest incomes. The new State Children’s Health Insurance Program (SCHIP), enacted by Congress in 1997 at an annual cost of $4 billion, is one such effort. By April of 2000, SCHIP had insured an estimated one million of the 2.5 million low-income children who are eligible. As SCHIP shows, even providing insurance coverage to only a small fraction of the uninsured will not be cheap. It also highlights the necessity of changing immigration policy so that it does not continue to add to the problem.

Conclusion

In any discussion of the impact of immigration on the size of the uninsured population, it is important to keep in mind that immigration is different from other factors that have contributed to the problem because it is a discretionary policy of the federal government. The federal government controls both legal immigration and the level of funding to control illegal immigration. Even if it were desirable, Congress cannot legislate a pause in the advance of medical technology or easily reduce the strong demand for health care in an aging and increasingly secular society, both of which have driven up costs. But it can change immigration policy.

Why Has the Problem Been Ignored?

Part of the reason policymakers and researchers interested in health insurance coverage have not devoted much attention to immigration’s role in this growing problem is that they have generally been focused on other issues such as rising health care costs, changing employment practices, and Medicaid eligibility. In addition, only in 1994 did the Census Bureau begin to ask a nativity question on a regular basis as part of the CPS, making it possible to measure the impact of immigration. Moreover, immigrants are not politically powerful, so politicians can ignore them without paying much of a political price. Additionally, elected officials may be reluctant to call attention to the fact that a policy they have either supported or at least not tried to modify has led to an enormous growth in the uninsured population.

Another important reason the problem has not received the attention it should stems from the fact that most of the advocates for immigrants are also advocates for the current high level of immigration. These advocacy groups cannot call too much attention to the fact that immigration is responsible for a large share of the growth in the uninsured population because to do so would highlight a fundamental problem with the very policy they work so hard to keep in place. Calling for costly new programs to provide health coverage to immigrants would undermine the argument made by the advocates that high immigration is an economic and fiscal boon to the country. This conflict of interest between being an advocate for immigrants and an advocate for mass immigration means that relatively little attention is paid to the millions of immigrants and their children without adequate health care.

A Problem that Cannot be Ignored

While some may be tempted to ignore the lack of health insurance among immigrants and their children at a time of relative prosperity, this seems very unwise. In just the last four years immigration has increased the size of the uninsured population by 2.7 million people. Without a change in immigration policy and greater efforts to increase health care coverage among immigrant families already in the country, the problem will only grow much worse. The implications of this situation for the immigrants themselves, their children, the nation’s health care system, and society are too important to ignore.

Introduction

A large body of research indicates that, at least since 1987, both the number and percentage of U.S. residents who do have health insurance has been on the rise (Fronstin, 1998; Lewis, Ellwood, and Czajka, 1998). In 1999, the Census Bureau reported that nearly one out of six persons in the United States lacked health insurance in 1998, and the total size of the uninsured population now stands at more than 44 million (Campbell, 1999). Health care in general and the problem of the uninsured in particular have become the subject of intense national debate and the discussion over what to do about the uninsured has taken center stage in the current presidential race. Both presidential candidates have made major policy speeches on the subject and proposed significant new initiatives to deal to with the growing problem. Governor Bush has proposed tax credits costing an estimated $34.7 billion over five years to low-income families so that they can afford to purchase insurance. Vice President Gore has also proposed tax credits for the uninsured as well as an expansion of the Medicaid system, with an estimated total cost of $146 billion over 10 years (Mitchell, 2000). As these and other proposals suggest, fixing the problem is likely to be very costly, no matter what solutions are envisioned.

The increase in the size of the uninsured population has grown worse throughout the 1990s, despite a strong economy and the lowest unemployment rate in years. Examinations of the problem have generally focused on broad trends in employment practices, the costs of health care and health insurance, changes in eligibility for Medicaid and other government programs, or the socio-demographic characteristics of the uninsured (Fronstin, 1998; Budetti et al., 1999; Lewin and Altman, 2000; Holahan and Brennan, 2000). To date, however, relatively little effort has been made to evaluate the impact of immigration policy on the size of the uninsured population. This report looks at the composition of persons without health insurance. The findings indicate that nearly one in three persons living in households headed by immigrants (primarily immigrants and their children) have no health insurance and that immigrant households now account for one-fourth of the uninsured. Moreover, newly arrived immigrants and their children account for more than half of the growth in the size of the uninsured population in recent years. Immigration policy has become central to understanding the growing health care insurance problem in the United States.

Trends in Health Insurance

Prior to the Second World War, few Americans had health insurance of any kind. Because of wage controls imposed during the war, employers began to offer non-wage compensation, such as health insurance, in an effort to attract and retain workers (Styring and Jonas, 1999; Health Policy Consensus Group, 1999). Early on, the Internal Revenue Service ruled that such compensation was not taxable. This made and continues to make employer-provided health insurance more favored as a means of insurance purchase than for individuals to buy their own insurance with after-tax dollars. As a result, employers became the primary source for health insurance for most Americans in the workforce. From the 1940s on, health insurance primarily took the form of a fee-for-service coverage system under which health care providers were paid by insurance companies for each treatment given. The lack of cost controls in the fee-for-service system, demand for expensive new technologies and treatments, heavy government spending on health care, and other factors created upward pressure on health care cost in the 1980s that reached double-digit annual increases by 1990. Because of rising costs, many employers turned to managed care to insure employees.

While managed care has been partly successful in stemming the rise in health care costs, insurance remains very expensive. This has made it much more difficult for employers, especially small businesses, to provide coverage. As a result, fewer employers offer health insurance today than in the recent past. Moreover, many employers who do offer health insurance now pass along a larger share of the costs to employees. Because of the limited value of their labor in an economy that increasingly demands educated workers, less-skilled workers in particular are the most likely to hold jobs that do not have health insurance as a fringe benefit or, if insurance is offered, the employee must pay a large share of the costs. Those under the age of 65 whose employers do not provide health insurance, must purchase it for themselves and their children if they are not covered by another family member’s insurance or if they are not eligible for government-provided insurance under the Medicaid or SCHIP systems. Because individually purchased policies, in most cases, are bought with after-tax dollars and are not granted the same full tax deductibility and groups rates available to employers, individual plans can be prohibitively expensive. This, of course, is especially true for low-wage workers and their families, who are the least likely to be in a position to afford private insurance and who may choose not to accept insurance offered by their employers if a large percentage of the costs is borne by the worker (Campbell, 1999; Styring and Jonas, 1999; Health Policy Consensus Group, 1999).

Over the last decade the Census Bureau has tracked the size of the uninsured population using the Current Population Survey. In 1987 an estimated 31 million U.S. residents lacked insurance. Since 1987, the size of the uninsured population has grown by more than one million people per year on average. Moreover, the proportion of the population lacking health insurance has increased from 12.9 percent of the population in 1987 to 16.3 in 1998. This increase continued even after the recession of the early 1990s. Between 1992 and 1998, the size of the uninsured population grew by 5.6 million and the proportion of the population without insurance increased by 1.3 percentage points. This increase in the uninsured population has puzzled some health care experts because the generally favorable economic condition for most of the 1990s reduced unemployment and should have created pressure on employers to offer health insurance as a means of attracting and retaining workers in a tight labor market.

Recent Trends in Immigration

Partly as a result of changes made in immigration law in the mid-1960s, as well as subsequent changes, the level of immigration has been rising steadily for the last three decades. At present, between 700,000 and 900,000 legal immigrants and an estimated 420,000 illegal immigrants settle permanently in the country each year (Statistical Yearbook of the Immigration and Naturalization Service, 1997). As a result, the immigrant population has grown rapidly, almost tripling in number from 9.6 million in 1970 to 26.5 million by the beginning of 1999, not including the U.S.-born children of recent immigrants.

As the level of immigration has increased over the last three decades, the education level of each new wave of immigrant has declined in comparison to natives (Borjas 1999; Edmonston and Smith, 1997). Because education has become so central to economic well-being in the modern American economy, this decline has prompted many to worry that immigrants may be falling behind natives in a variety of social measures. One of the most worrisome consequences of declining immigrant skills is that a large percentage may end up in jobs that pay poverty-level wages and provide few non-monetary fringe benefits—including health insurance. Under such circumstances a large share of immigrants and their dependents would not only lack employment-based health coverage, they also would find it difficult to purchase it privately given their limited financial resources.

Purpose of Research

The overriding goal of this paper is to help bridge the gap between health insurance and immigration policy circles. As this paper will make clear, the two issues are much more intimately linked than is commonly supposed. To this end we first examine the direct effect immigration has on the size and growth of the uninsured population at the national level, and where possible at the state and local level, using the latest data available. Second, in order to better understand why immigrants and their children lack insurance, this paper provides detailed information on the socio-demographic characteristics of the uninsured based on whether they reside in a native- or immigrant-headed household. It is our hope that this will help to better inform policymakers, researchers, and others interested in the ongoing debate over health care and immigration.

What Does it Mean to be Uninsured?

There are, of course, many different kinds of health insurance. Moreover, tests and procedures covered, drug benefits, ability to choose one’s doctor, deductibles, and total benefit limits vary widely among plans. This paper relies on the definition of insurance used in the Census Bureau publication, Health Insurance Coverage 1998: Current Population Report P60-208. We also use the same data source used in that report, the March 1999 Current Population Survey (CPS) collected by the U.S. Census Bureau. While other data sources are also used, much of the previous research, as well as figures published by the federal government on the uninsured, relies on this definition and data source.1

A person is considered to have health insurance if he or she responds yes to any of a series of questions that ask whether the person was covered by insurance provided by an employer (including insurance provided to military personnel, veterans, and their families), or whether he or she was covered by a family member’s policy, Medicare, Medicaid,1 or insurance purchased by him- or herself during the year prior to the survey. These questions are designed, according to the Census Bureau, to measure whether an individual was without health insurance coverage during the entire calendar year. Based on the March 1999 CPS, persons who responded that they did not have any type of health insurance in the prior year are considered to have been uninsured for all of 1998.

Why Study Immigration’s Impact on the Size of the Uninsured Population?

In any discussion of immigration’s impact on the size of the uninsured population, it is important to keep in mind that immigration is different from other factors that may have contributed to the problem because immigration is a federal policy. The federal government controls both the number of legal immigrants allowed into the country each year and the selection criteria used for admission. Moreover, the federal government determines the level of resources and the tactics devoted to controlling illegal immigration. Thus, the level of immigration and the composition of the immigrant population stems directly from federal policy — a policy that can be altered at any time. Even if it were desirable, the government cannot legislate a pause in the advance of medical technology or easily reduce the strong demand for health care in an aging and increasingly secular society, two factors which have driven up costs. But it can change immigration policy.

One may still reasonably ask if it matters what proportion of persons in immigrant households, or even in native households for that matter, do not have health insurance. What effect, if any, does a lower national or local rate of health insurance coverage have on the country as a whole or in a particular part of the country, especially for the majority of the population who do have health insurance? In addition to altruism, there are a number of very practical reasons to be concerned about the level of insurance coverage in America and the role that immigration policy may be playing in this growing problem.

Impact on The Uninsured Already Here

Probably the most obvious reason for concern is the impact on the uninsured already here, both native and immigrant. The cost of efforts to provide insurance to those without it or to provide basic care if more comprehensive insurance is not provided, depends in large part on the number of people in need of such assistance. If immigration increases the number of people who require government financed or subsidized health care, then the total cost of such efforts must grow accordingly. Increasing the total cost of efforts to provide insurance and health care to the uninsured can only reduce political support for such efforts. Alternately, if federal, state, and local government outlays on programs for the uninsured remain relatively constant, then the level of services provided to each recipient must be reduced. This, too, is clearly not in the interest of America’s uninsured. A large increase in the size of the uninsured may also strain the resources of non-governmental institutions and charities that provide health care to the uninsured, thereby reducing what they can provide to each individual. A recent report from the Institute of Medicine concluded that the financial viability of institutions that provide health care to the uninsured is more at risk today than in the past; partly because of the rising number of uninsured individuals (Lewin and Altman, 2000). Therefore, if one is concerned about the uninsured already here, significantly increasing the size of the uninsured population is clearly counterproductive. This is likely to be the case no matter what solution is favored to deal with the problem.

Effect on Taxpayers

Probably the most self-interested reason to be concerned about a rise in the uninsured population resulting from immigration is its effect on public coffers. The uninsured still become injured or ill and need medical attention. While their options may be more limited, not having health insurance does not mean that uninsured patients receive no medical care. Rather, they often postpone medical attention until their condition has worsened (Budetti et al., 1999). The uninsured seek treatment from "safety net providers," such as public hospitals, community health clinics, and local health departments (Lewin and Altman, 2000; Gage and Regenstein, 1999). Thus, individuals without insurance do receive care, but often it is the most expensive and least efficient means of obtaining treatment.

In many cases, the cost of providing medical services to the uninsured is paid for by federal, state, and local governments. For many counties and cities, the costs of operating a public hospital and/or clinics, which provide much of their services to the uninsured, account for a sizable portion of their total budget. In addition, health care providers are often reimbursed by the federal government for costs incurred in providing care to the uninsured. The amount of public money that goes to provide health care to the uninsured is substantial. Because of the diversity of funding sources, the complex and decentralized way in which they are administrated, and the limited availability of data, no exact estimate exists for the total public cost of providing care to the uninsured. It is likely, however, between $15 and $30 billion per year is spend on the uninsured by government at all levels.3 These costs do not include the more than $150 billion spend annually by the federal government and states to provide Medicaid coverage to low-income residents. Whatever the cost of providing services to those without insurance, there can be no doubt that an increase in the size of the uninsured population resulting from immigration has significant negative implications for taxpayers.

Higher Premiums and Costs for Those with Insurance

While governments at all levels do compensate health care providers for some of the care given to the uninsured, a significant portion of the care is not compensated and must be simply written off by providers as charity because collecting money from the uninsured can be very difficult given their limited financial resources in most cases. (Lewin and Altman, 2000). Hospitals and other health care providers simply cannot absorb all of the costs of providing such charity care and so they pass at least some of the costs along to paying customers in the form of higher prices for treatment, which in turn creates higher insurance premiums for those with insurance. There is evidence, however, that in the new managed-care environment, cost-shifting has become difficult for health care providers, though it is clear that some cost-shifting continues to occur from those with insurance to those without (Morrisey 1996).

For workers whose employers pay for all or almost all of their health care premiums, these costs remain largely hidden (Castro, 1994). But in the long run, the rising costs associated with providing care to the uninsured must make employers increasingly reluctant to offer it or to require employees to pay an ever larger share of the premiums. The higher costs caused by the uninsured may also force some employers with limited financial resources, who wish to continue to provide coverage, to offer smaller wage increases or curtail other fringe benefits so that they can continue to afford higher insurance payments. The situation is even worse for Americans who must purchase their own insurance without the aid of an employer, because they will be forced to bear the costs of higher premiums directly, without an employer to share part of the increase.

In this way a growing uninsured population creates its own momentum by making it more likely that employers will shift the costs of insurance to their employees and by pushing the costs of insurance out of reach for Americans with moderate incomes who must purchase insurance on their own. There can be little doubt that increases in the cost of health insurance can only make it more difficult for employers and low-income Americans to afford health insurance. Thus, while it may appear at first glance that the growth in the uninsured population is of little concern to those who have insurance, this is clearly not the case.

In modern America, at least some services will always be provided to those without insurance, even if the costs of doing so are high. Thus, the size of the uninsured population should be of concern to all members of society because all members will have to pay for these costs through higher taxes, higher premiums, or some combination of the two.

Increasing the Risk for the Spread of Communicable Diseases

In addition to monetary concerns over the costs of the uninsured, there are also very real public health issues associated with a large uninsured population. Because they often do not receive routine preventive care and often seek out medical attention only when their condition is more serious, the uninsured may unintentionally extend the period of time the public is exposed to communicable deceases. This problem is likely to be of particular concern among immigrants because most come from developing countries where communicable diseases are more common. For example, tuberculosis in the United States is disproportionately concentrated in the immigrant population. In 1998, about 42 percent of the 18,361 known cases in the United States were among immigrants (Sachs, 2000). The resurgence of TB, especially strains of the disease that are drug resistant, constitutes a growing health care threat. If many immigrants are uninsured, this may represent a significant impediment to dealing with this problem. At the very least, it is clear that a lack of health insurance among immigrants has important implications for the health of the entire society.

Implications for Immigrant and Immigration Policy

In addition to the impact on native-born Americans, looking at insurance among immigrants and their children is also important because it is one way of evaluating the consequences of current immigration policy. Perhaps most important, it also gives us a good idea of how immigrants admitted in the future are likely to do in the United States if immigration policy remains unchanged. Having health insurance and access to health care is one measure of incorporation and integration in the economic and social mainstream. Low rates of coverage imply that, for whatever reason, a significant proportion of immigrants have not successfully adapted to life in the new country, at least with regard to health insurance. This is particularly important because, without a change in immigration policy, 10 million new immigrants will likely settle permanently in the United States in just the next decade. If current trends continue, immigration may add an additional three to four million people to the ranks of the uninsured over just the next 10 years. Of course, the extent to which persons in immigrant households have health insurance today does not tell us exactly how those admitted in the future will fare. Looking at past immigrants, however, is probably the best means we have of predicting how tomorrow’s immigrants will do if the same selection criteria for admission continue to be used.

In addition to immigration policy, which is concerned with who may come and how many, there is immigrant policy, which deals with how we treat the foreign-born living in United States. Looking at health insurance coverage among immigrants is important because if a large percentage of immigrants and their children already here lack insurance, we need to deal with this problem in a constructive manner, whatever immigration policy is adopted in the future. Such things as tax incentives to employers so that they will provide coverage for employees, increasing immigrant use of government-provided health insurance for which they are eligible but do not use, and efforts to improve the labor market skills of immigrants so that they find jobs that offer insurance may all need to be designed with the intent of addressing the particular needs of immigrants. At the very least, if immigrants and their children now comprise a large share of the uninsured, our efforts to deal with this problem, as well as research on health insurance coverage, must take this new reality into account.

Methods and Data

Definitions and Data Sources

The data for this study come from the March 1999 Current Population Survey (CPS) collected by the Census Bureau. The CPS is used because it is the most recent survey available and is the source of most official government statistics on the uninsured. Moreover, it is one of the best sources of information on persons born outside of the United States—referred to as foreign-born by the Census Bureau.4 Persons not born in the United States, one of its outlying territories, or to U.S. parents living abroad are foreign-born. All persons born in the United States, including the children of illegal aliens, are natives. For the purposes of this paper, foreign-born and immigrant are used synonymously.

As already described, this paper relies on the definition of insurance used in the government’s publication, Health Insurance Coverage 1998: Current Population Report P60-208. Persons are considered to have health insurance if they respond "yes" to any of a series of questions that asks whether they were covered by insurance in the year prior to the survey provided by an employer, family member’s policy, the government, or by insurance they purchase themselves. Since the survey was conducted in March 1999, it measures insurance coverage for 1998. No adjustments of any kind are made to the definition of insurance or the data in this paper. Totals for the uninsured presented here match those published by the Census Bureau.

This paper examines insurance coverage for persons living in immigrant- and native-headed households. Individuals related to the household head by blood, marriage, or adoption, regardless of their own nativity, are considered to be in an immigrant or native household based on whether the household head is foreign-born or a native. Individuals unrelated to the head are considered immigrant or native based on the nativity of the head of the family in which they reside. For example, a foreign-born husband and wife (one of them would be the head) with two young U.S.-born children are counted as a household of four people living in an immigrant household. If the same family were to rent a room to an unrelated native-born woman with a child of her own, then the woman and her child would be counted as a separate native household, even though she and her child live under the same roof as the immigrant family and are technically in the same household as the immigrant family. Persons who live by themselves or with others to whom they are unrelated are, in effect, their own households and are considered immigrant or native based on their own nativity. Households are defined in this way so that they more accurately reflect the kind of income sharing and insurance eligibility that exists among members of the same family. Its worth noting that individuals unrelated to the household head only comprise about 4 percent of the population, therefore how they are allocated does not substantially affect the results.

Composition of Immigrant Households

Using the above definition, 92.4 percent of the people living in immigrant-headed households were immigrants themselves (67.3 percent) or the native-born child under age 21 (25.1 percent) of an immigrant father or mother based on the March 1999 CPS. In households headed by immigrants who arrived after 1970, 96.3 percent of the people are either immigrants or their U.S.-born children under the age of 21. Therefore, this approach primarily measures insurance coverage for immigrants and their children. Since a child’s standard of living, including access to health insurance, is a function of his parents’ income, this method captures the full effect of immigration on the size of the uninsured population in the United States. Unless otherwise indicated, country of origin and year of entry for immigrant households are based on the responses of the household head.

Findings

High Percentage of Persons in Immigrant Households Lack Insurance

Figure 1 shows the proportion of persons in immigrant- and native-headed households who have no health insurance, also referred as the uninsured. Figure 1 also shows the percentage who are covered by Medicaid, the means-tested health insurance program provided by the federal government and states. (The figures for Medicaid include persons using the Indian Health Service as well as state programs, such as California’s Medi-Cal). In 1998, 32.4 percent of all persons in immigrant households were without health insurance. This was more than twice the rate for persons in native households — 13.9 percent of whom lacked health insurance. This means that, astonishingly, nearly one out of three persons in immigrant households had no health insurance in 1998. The difference in rates of insurance coverage is statistically significant using either a 90 percent or 95 percent confidence level. This means that we can say with 95 percent certainty that the gap in rates of insurance coverage in the CPS represents a real difference in the actual population.

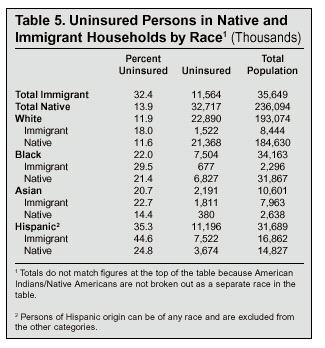

Compared to other subgroups in the population, the percentage of persons without health insurance in immigrant households is extremely high. Even in comparison to groups that traditionally have a high percentage without insurance, the rate for those in immigrant households stands out. For example, it exceeds the rate for African-Americans, 22.2 percent of whom lack insurance, and also exceeds the rate for high school dropouts,5 26.7 of whom lack insurance, and it is about equal to the 32.3 percent of all persons living in poverty who are uninsured. If many observers have described the fact that 16.3 percent of the nation’s total population lacks insurance as a severe problem, then the situation for immigrants and their children can only be described as a crisis.

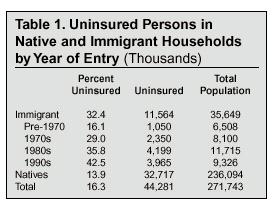

Immigrant Households Account for a Large Share of Uninsured Population

The high percentage of persons in immigrant households without insurance coupled with the very large number of people living in immigrant households means that immigration has had a very significant effect on the overall size of the uninsured population. Table 1 provides percentages and totals for persons without health insurance living in immigrant and native households. In 1998, persons in immigrant households accounted for 26.1 percent or 11.6 million of the 44.3 million people in the United States who lacked health insurance. Since persons in immigrant households account for only 13.1 percent of the country’s total population, their disproportionate representation among the uninsured reflects the very high percentage who do not have health insurance. Put another way, the uninsured population is one-third larger (32.7 million versus 44.3 million) because of immigration. Clearly, the impact of immigration on the health insurance problem in the United States is difficult to overstate.

Welfare Reform is Not to Blame

In 1996, concern over immigrant use of means-tested programs led Congress to reduce welfare eligibility for some immigrants as part of a general overhaul of the welfare system. In particular, Congress made some recent non-humanitarian immigrants (i.e., not refugees and asylees) ineligible to receive several federally funded programs, including SSI, AFDC/TANF, and food stamps, until they had been in the country for a certain period of time. Since persons receiving cash assistance programs like SSI and AFDC/TANF are automatically eligible for Medicaid coverage, changes in immigrant eligibility for these programs might explain why so many persons in immigrant households do not have health insurance. The available evidence, however, indicates that this is clearly not the case. Lack of insurance coverage was a severe problem for persons in immigrant households before welfare reform. In 1995, 30.5 percent of persons in immigrant households were uninsured.6 This is very similar to the 32.4 percent who were uninsured in 1998. Moreover, the gap between persons in immigrant and native households has remained roughly the same size since 1995. In that year, 13.2 percent of persons in native households lacked health insurance, so there was a 17.3 percentage point gap between immigrant and native households. This is only slightly smaller than the 18.5 percentage point gap that existed in 1998 between the two groups. It is true that Medicaid use among persons in immigrant households has fallen significantly since 1995, but it has also fallen sharply for persons in native households. Between 1995 and 1998, Medicaid use declined 15 percent for persons in native households and a little less than 18 percent for persons in immigrant households. As Figure 1 shows, despite falling Medicaid use, persons in immigrant households are still significantly more likely to be on Medicaid than those in native-headed households.7 In 1998, 13.8 percent of persons in immigrant households used Medicaid compared to 9.7 percent of people in native households. Since the percentage of persons in immigrant households on Medicaid remains higher than that of persons in native households, it is hard to argue that low rates of Medicaid use alone account for the higher percentage of immigrants and their children who are uninsured.

The fact that welfare reform does not explain the lack of insurance coverage for persons in immigrant households does not mean that Congress was right to curtail welfare eligibility for immigrants. As we will see, the low level of educational attainment and high poverty rates of many immigrants and their children indicates that they need access to the welfare system even more than do natives. While it may make little sense to have an immigration policy that admits large numbers of people who end up in or near poverty and need to use means-tested programs, cutting welfare benefits to immigrants after they have already been allowed into the country seems neither fair nor wise.

Recent Immigration Accounts for Much of Growth in the Uninsured Population

One of the reasons policymakers, politicians, the media, and researchers have devoted so much attention to the uninsured population is that it has grown significantly in recent years. As previously discussed, both the percentage of the population without health insurance and the size of the uninsured population have grown significantly in recent years. The growth in the uninsured population continued through the 1990s, despite a strong economy over most of the decade. What has not been generally acknowledged is that much of this increase was caused by newly arrived immigrants and their children. The Current Population Survey asks immigrants when they came to the United States. therefore, it is possible to estimate the direct impact of recent immigration on the size of the uninsured population. In 1998, 2.58 million of the 5.32 million immigrants who indicated that they had arrived between 1994 and 1998 lacked health insurance. In addition, 114,000 of the 424,000 children born in the United States to immigrants that arrived in this time period also lacked health insurance.8 This means immigration accounted for 2.7 million or an astonishing 59 percent of the 4.67 million increase in the size of the uninsured population that took place after 1993. Looked at from a different point of view, if all persons in immigrant households are excluded from the data, the percentage of the population without health insurance in the United States would be 13.9 percent (the current rate for persons in native households and the national rate back in 1990). These numbers indicate that immigration policy has become central to an understanding of the growing health care insurance crisis in the United States. Without immigration, the size and scope of the problem would be significantly different.

Lack of Insurance Remains a Problem Even After Many Years in the Country

While recent immigrants and their children account for much of the recent growth in the uninsured population, this would not be as much a matter of a concern if immigrants obtained insurance soon after arriving in the country. In addition to overall totals, Table 1 reports the percentage of persons who lack health insurance based on the year of entry of the household head. Looking at insurance coverage by entering cohort is useful because it is one of the best ways of determining the progress of immigrants over time. Table 1 shows that the longer immigrants reside in the United States, the more likely they are to have health insurance. This is certainly to be expected. As immigrants become more familiar with their new country and as their work experience grows, their access to health insurance increases. However, the table also shows that even after immigrants have been in the country for a long period of time, the percentage without health insurance remains extremely high. For example, 35.8 percent of persons living in households headed by an immigrant who arrived in the 1980s still did not have insurance in 1998, even though in most cases the household head had been in the country for 10 or more years. Turning to persons living in households headed by immigrants who arrived in the 1970s, 29 percent were without coverage, even though most of the heads of these households had been in the country for more than 20 years. With the exception of pre-1970 immigrant households, the differences between persons in immigrant and native households by year of entry is statistically significant. The higher rates of insurance coverage of pre-1970 immigrants may partly reflect the fact that most of these immigrants were admitted under the system that existed prior to 1965, which tended to produce a more educated flow of immigrants. The results in Table 1 make clear that although the percentage without insurance does decline over time, many persons in immigrant households do not acquire insurance even after they have been in the country for many years.

The figures in Table 1 report insurance coverage for all persons in immigrant households. One might assume that the immigrant themselves have much higher rates of insurance coverage, but that it is their dependents who are often without insurance. Analysis of only immigrants, however, indicates that this does not appear to be the case. In 1998, 27.2 percent of immigrants who arrived in the 1970s were without insurance; for 1980s immigrants, the figure was 37 percent and for immigrants who arrived in the 1990s, 47.2 percent lacked insurance. While these percentages differ somewhat from those in Table 1, the same basic pattern remains. Even after they have lived in the United States for many years, lack of insurance coverage among immigrants is very common. These findings indicate that despite generally favorable economic conditions over the last two decades, many immigrants are unable or are unwilling to acquire health insurance. Even 1970s immigrants are twice as likely as natives to be uninsured. The fact that such a high percentage of established immigrants do not have insurance raises the question of whether low rates of insurance coverage, at least to some extent, reflect a choice on the part of some immigrants, rather than economic necessity. This issue will be explored later in this report.

Majority in Immigrant Households Without Insurance Are Legal Residents

While Table 1 indicates that persons in immigrant households make up a large share of the uninsured, it does not provide information about their legal status. It is possible that illegal aliens (also called undocumented or unauthorized immigrants) account for a large percentage of persons in immigrant households without insurance. Knowing the legal status of those who lack insurance may be important because it provides useful information about the extent to which the problem is explained by the presences of illegal immigrants in the country. While it is not possible to definitely identify illegal aliens in the CPS, it is possible to estimate their number and their rate of insurance coverage. Research by Clark and Passel (1998) and Warren (1999) indicates that five million illegal aliens were counted in the March 1999 CPS.9 To estimate the percentage who lack insurance, it is possible to use persons with demographic characteristics that are thought to be similar to those of illegal aliens. This paper uses immigrants who are not citizens; who lack a college education; who are under age 65; who are from Mexico, the Caribbean (excluding Cuba), and Central America; and who arrived between 1986 and 1998 as representative of illegal aliens. In the March 1999 CPS, the percentage of these individuals who lacked insurance was very high — 63.9 percent. To calculate the impact of illegal aliens on the size of the uninsured population, we assume that the same percentage of illegals (96.9 percent) live in immigrant households as our surrogate population. If the rate of insurance coverage and distribution across households is the same for illegal aliens as for this surrogate population, then 3,095,955 or 26.8 percent of the 11,564,000 people without insurance living in immigrant households are in the country illegally. Alternately, 73.2 percent or 8,468,045 of persons in immigrant households were legal immigrants or the U.S.-born children of immigrants. These results also imply that 27.5 percent of persons in immigrant households who reside in the country legally are without health insurance. While this is somewhat lower than the 32.4 percent for all persons in immigrant households when illegal aliens are included, it is still dramatically higher than the 13.9 percent for persons in native households. Clearly, these estimates indicate that illegal aliens contribute significantly to the problem. However, they also indicate that illegals account for only about one quarter of persons in immigrants households who do not have insurance. Even when illegals are excluded, the 27.5 percent of persons in immigrant households who are without insurance is still about twice the rate for individuals in native households.

The estimates provided above probably overstate the impact of illegal immigration for two reasons. First, defining who is an illegal alien is not as straightforward as it might seem. A large percentage of those in the country "illegally" actually have the permission of the federal government. Many are asylum applicants awaiting the outcome of their petition to stay in the country. Others enjoy temporary protected status (TPS) because, although they do not qualify for political asylum, the federal government will not deport them or require them to leave because it is thought conditions in their home countries are too unstable or chaotic for them to return. In addition, there are still several hundred thousand persons who are the spouses and children of amnesty beneficiaries from the 1980s who are also allowed to stay in the country. If all of these "semi-legal" immigrants are excluded, illegal aliens would account for an even smaller share of those without insurance living in immigrant households.

The second reason that the estimated impact of illegal aliens may be overstated in the above calculations is conceptual. It may make more sense when evaluating the impact of immigration to view legal and illegal immigration as closely linked and not as distinct phenomena. Many illegal aliens come to the United States to join friends and family members who are legal residents. Sociological research indicates that one of the primary factors influencing a person’s decision to emigrate is whether a family member or person from their home community has already come to United States (Massey and Espinosa 1997; Palloni, Spittel, and Ceballos 1999). Communities of recent legal immigrants serve as magnets for illegal immigration by providing housing, jobs, and entree to America. The close link between legal and illegal immigration can also be seen in analysis done by the Congressional Research Service that estimates that one out of four legal immigrants who receives a green card in any given year is in fact an illegal alien already living in the country (Cited in Vaughan,1997). Thus, it is probably more accurate to view illegal immigration as a direct consequence of large-scale legal immigration and not as a separate phenomenon. If this is correct, it makes more sense to look at the characteristics of all immigrants as reflective of the nation’s immigration policy in its totality, not to separate out illegal aliens from legal immigrants.

Socio-Demographic Characteristic

Insurance Coverage by Educational Attainment

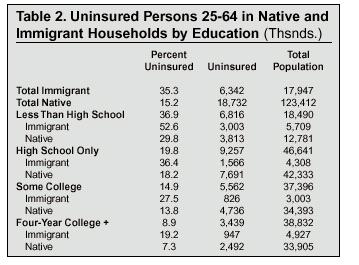

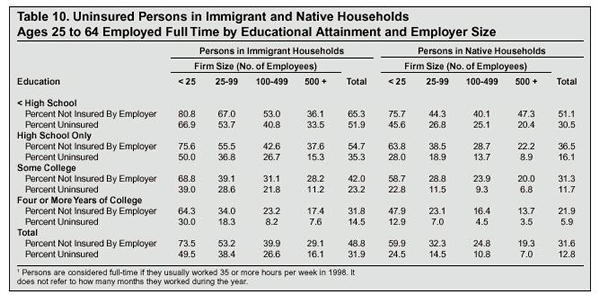

One of the best predictors of the propensity to have insurance is a person’s education level, regardless of nativity or income. This is true for several reasons. First, because of the limited value of their labor in an economy that increasingly demands more skilled workers, those with little education are the most likely to hold jobs that do not offer health insurance as a fringe benefit or, if insurance is offered, the workers must pay a large share of the costs. Second, those with little education have the lowest incomes and may find it very difficult or simply impossible to afford to insurance on their own. Third, persons with few years of education have the most unstable employment histories—suffering higher unemployment rates and longer periods of unemployment than educated workers whose skills are more in demand. Since loss of insurance often accompanies loss of employment, higher rates of unemployment should have an effect on rates of insurance coverage. Table 2 reports the health insurance coverage of persons between 25 and 64 years of age in immigrant and native households by educational attainment. The table indicates that insurance coverage varies enormously based on education level, regardless of nativity. In 1998, 36.9 percent of all dropouts were without insurance; for persons with only a high school education, 19.8 percent were uninsured; for those with some college, 14.9 percent had no insurance; and 8.9 percent of individuals with four years of college were without health insurance. Since persons aged 25 to 64 in immigrant households are much more likely than those in native households to lack a high school education (31.8 percent compared to 10.4 percent), the high percentage of persons in immigrant households who have no insurance is at least partly explained by the higher proportion with few years of schooling.

Table 2 also shows, however, that education alone does not account for the lower rate of insurance coverage associated with immigrants. At every education level, adults in immigrant households are twice as likely as adults in native households to lack insurance. Thus, a lower level of education is by no means the only factor accounting for the high percentage of persons in immigrant households who lack insurance.

One way of examining the importance of education in explaining the lack of insurance associated with immigrants is to calculate the rate of coverage for persons 25 to 64 in immigrant households, assuming that their educational endowment was the same as persons in native households. In other words, what percentage of working age adults in immigrant households would lack insurance if their distribution across educational categories was the same as persons in native households and their rate of insurance coverage by education was unaltered. In 1998, if persons in immigrants households had the same educational endowment as natives, but retained the same rates of coverage by educational category, 30.9 percent of persons in immigrant households would have been without insurance. While this is less than the actual 35.3 percent who lacked insurance in 1998, it is still dramatically higher than the 15.2 percent for working-age adults in native households. This suggests that 4.4 percentage points or 22 percent of the 20.1 percentage point gap in the insurance coverage for persons 25 to 64 in immigrant and native households is accounted for by the lower levels of education associated with immigrants. While these results indicate that education is clearly an important factor, the causes of the problem are more complex. Other factors must also contribute significantly to the lack of insurance for individuals in immigrant households.

Insurance Coverage by Age

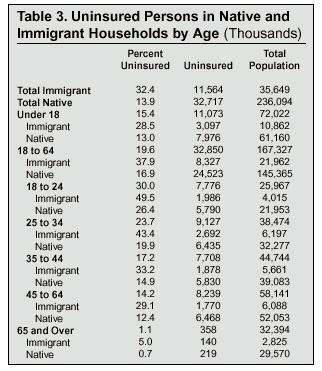

In addition to education, age also has an impact on one’s likelihood of having health insurance. Table 3 reports health insurance statistics by age for persons in immigrant and native households. As the table indicates, insurance coverage is less common among those 18 to 64 than for both children and older people. Most persons over 65 have insurance because all persons who receive Social Security, or who have a spouse who receives Social Security, automatically qualify for Medicare. While a larger share of persons in native households are over age 65 (12.5 percent compared to 7.9 percent for immigrants), this does not explain the difference in rates of insurance coverage between immigrant and native households. Even when retired persons are excluded, the gap between immigrants and natives remains.

Turning to children (17 and under) first, we see that overall they have a somewhat higher rate of insurance coverage than adults because children in low-income families are often eligible for government-provided means-tested insurance even when their parent are not. Since 1997, the federal government, along with the states, has had some success in increasing insurance coverage among children in low-income families under the State Children Health Insurance Program or SCHIP (Morse, 2000). Even so, about one in seven children in the United States was without health insurance in 1998.

Table 3 shows that children in immigrant households have much lower rates of insurance coverage than do their counterparts in native households. In 1998, 28.5 percent of children in immigrant households were without health insurance, compared to 13 percent in native households. The 3.1 million children in immigrant households who lack insurance now represent 28 percent of all uninsured children. There can be little doubt that recent immigration is making it more difficult and costly to reduce the number of children without insurance under SCHIP. Congress passed SCHIP in 1997 in an effort to increase insurance coverage among low-income children and it is expected to cost the federal government $20 billion over five years. By April of 2000, an estimated one million eligible children have been provided insurance as part of SCHIP (Morse, 2000). But immigration certainly has the potential to undo much of that progress. In 1998 there were 588,000 immigrants under the age of 19 (SCHIP’s target population) without insurance who had arrived in just the last four years. In addition, there were 114,000 children born to adult immigrants who arrived during the same period who did not have insurance in 1998. Thus, because of recent immigration the number of children without health insurance was more than 700,000 larger than it would otherwise have been, erasing most of the gains made so far under SCHIP. In the years to come, it is very likely that immigration may offset much of the progress made as a result of SCHIP

While the gap between children in immigrant and native households is very large, it is also extremely large for persons between the ages of 18 and 64 and for all subdivisions of that age group. Table 3 indicates that 37.9 percent of individuals in immigrant households between 18 and 64 lacked insurance in 1998, compared 16.9 percent of individuals in native households. This difference can only be described as huge, with those in immigrant households being more than twice as likely to lack insurance as those in native households. Table 3 also shows that differences in the age distribution between persons in immigrant and native households do not account for the dramatically lower rates of insurance coverage associated with immigrants. In some of the younger age groups, the gap between persons in immigrant and native households is actually larger than the gap among all persons in immigrant households and all persons in immigrant households. For example, there is a 23.1 percentage point gap between persons aged 18 to 24 in immigrant and native households. This difference is slightly larger than the 18.5 percentage point gap that exists when comparing all persons in immigrant households to all persons in native households. Therefore, the age distribution of persons in immigrant households would seem to account for little if any of the large difference between the two groups in insurance coverage. We must look elsewhere if we are to understand why so many immigrants and their children lack health insurance.

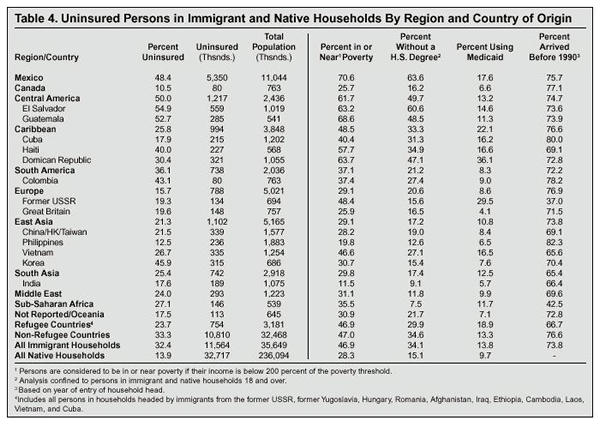

Insurance Coverage by Country and Region of Birth

Table 4 reports insurance coverage by regions of the world and country of birth based on the household head. Turning to region of birth first, the table reveals that while persons in immigrant households are much more likely to be without insurance than those in native households, there are substantial differences among immigrants. Persons in Mexican- and Central and South American-headed households are the most likely to lack health insurance. In contrast, households headed by Canadian and European immigrants are the most likely to have health insurance. The sizes of the differences between regions are very large in some cases. Persons in Mexican and Central American households, for example, are more than three times as likely to be uninsured as persons in households headed by immigrants from Europe and Canada.

While there are some immigrant groups who are about as likely as natives to have insurance, lack of health insurance coverage is widespread among immigrants and is not simply confined to a few groups. In addition to the very large share of persons in Mexican and Cental American households without insurance, persons in households headed by immigrants from Sub-Saharan Africa, the Middle East, South Asia, South America and the Caribbean are either twice as likely to be without insurance as are persons in native households or very nearly so. While it is clear that lack of health insurance is a much greater problem for some groups than others, low rates of insurance coverage is common among many immigrant groups.

In addition to insurance coverage by region of origin, Table 4 also reports the percentage uninsured for the 15 countries with the largest number of post-1970 immigrants living in the United States in 1998. Given the sample size of immigrants from some countries, however, the differences between countries should be interpreted with caution. Smaller sample size means that there is greater variability for individual country estimates than for the estimates based on region of origin. The estimates for individual countries should be used to make determinations of the relative differences between countries, and should not be seen as quantified absolute differences. Table 4 shows that like the data by region, rates of insurance coverage differ significantly by country. In fact, the variation between immigrant households from different countries is much larger than is the difference between persons in immigrant and native households. In 1998 for example, the percentage of persons without insurance in Salvadoran households was more than five times that of persons living in households headed by Canadian immigrants. Even among immigrants from the same region of the world, rates of insurance coverage vary significantly. For example, persons in Korean households are much more likely to be uninsured than immigrants from other East Asian countries. Among Caribbean immigrants, persons in Cuban household are much more likely to be uninsured than are persons in households headed by immigrants from that region.

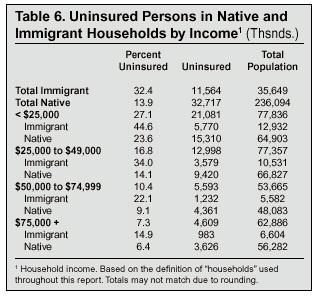

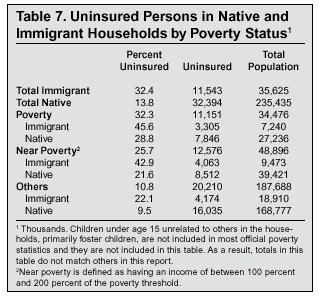

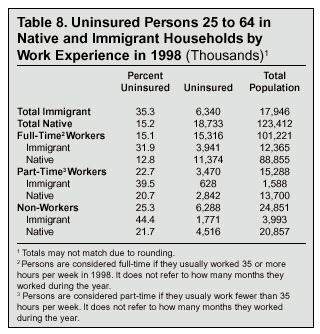

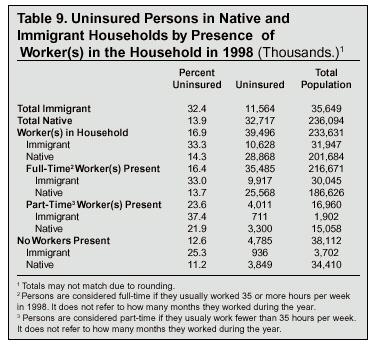

What Accounts for the Large Differences Between Immigrant Groups?