The argument that America needs to increase its rate of population growth has become common. Many opinion pieces and articles have bemoaned newly released census numbers showing that the U.S. population increased by “only” 22.7 million (7.4 percent) between 2010 and 2020. This compares to 9.7 percent between 2000 and 2010. In his new book, “One Billion Americans: The Case for Thinking Bigger”, Matthew Yglesias argues for a host of pro-natalist policies and massive increases in immigration that he believes would revitalize the country.

In a piece for CNN and a report for the immigration advocacy group fwd.us, George Mason University’s Justin Gest argues for doubling immigration to make the United States 166 million people larger in 2050 than it would be without any immigration. This, he contends, would make the country more “productive” and “richer”. In truth, there is no clear evidence that population growth necessarily improves a country’s standard of living.

To be sure, a larger population almost always results in a larger aggregate economy. More workers, more consumers, and more government spending will make for a larger GDP. But the standard of living in a country is determined by per capita (i.e., per person) GDP, not the overall size of the economy. If all that mattered were the aggregate size of the economy, then a country like India would be considered vastly richer than a country like Sweden because it has a much larger economy. In reality, per capita GDP determines a country's standard of living.

One might think that given all the voices calling for more population growth, there must be a large body of research showing that population growth increases per capita GDP. But that is not what the research shows. In a well-known meta-analysis, Derek D. Headey and Andrew Hodge examined dozens of previous studies that had looked for a relationship between population growth and per capita economic growth. They found evidence that population growth actually adversely impacts economic growth.

More recently, Ronald Lee and Andrew Mason found that low fertility — around the current rate in the United States — actually increases per capita economic growth and raises standards of living. They conclude that “low fertility is not a serious economic challenge.” Instead, they find that “The effect of low fertility on the number of workers and taxpayers has been offset by greater human capital investment, enhancing the productivity of workers.” They even add that “Targeted immigration policy might be helpful, although we are somewhat skeptical on this point.”

Straightforward comparisons of population growth and per capita economic growth tend to support the idea that population is not positively associated with per capita growth. Table 2 reports the population growth and per capita GDP growth over the last two decades based on World Bank data for OECD countries that are designated as high-income by the World Bank. (Figures showing per capita GDP in constant U.S. dollars for each country can be found here, and population by country can be found here.) If population growth drove economic growth, then countries like Canada and Australia that have among the highest rates of immigration and resulting population growth should vastly outpace a country like Japan, which has relatively little immigration and whose population actually declined over the last decade. And yet in the most recent decade for which we have data, (2010 to 2019), Japan’s per-capita GDP grew 10.5 percent, slightly better than both Canada’s 8.7 percent and Australia’s 9.9 percent.

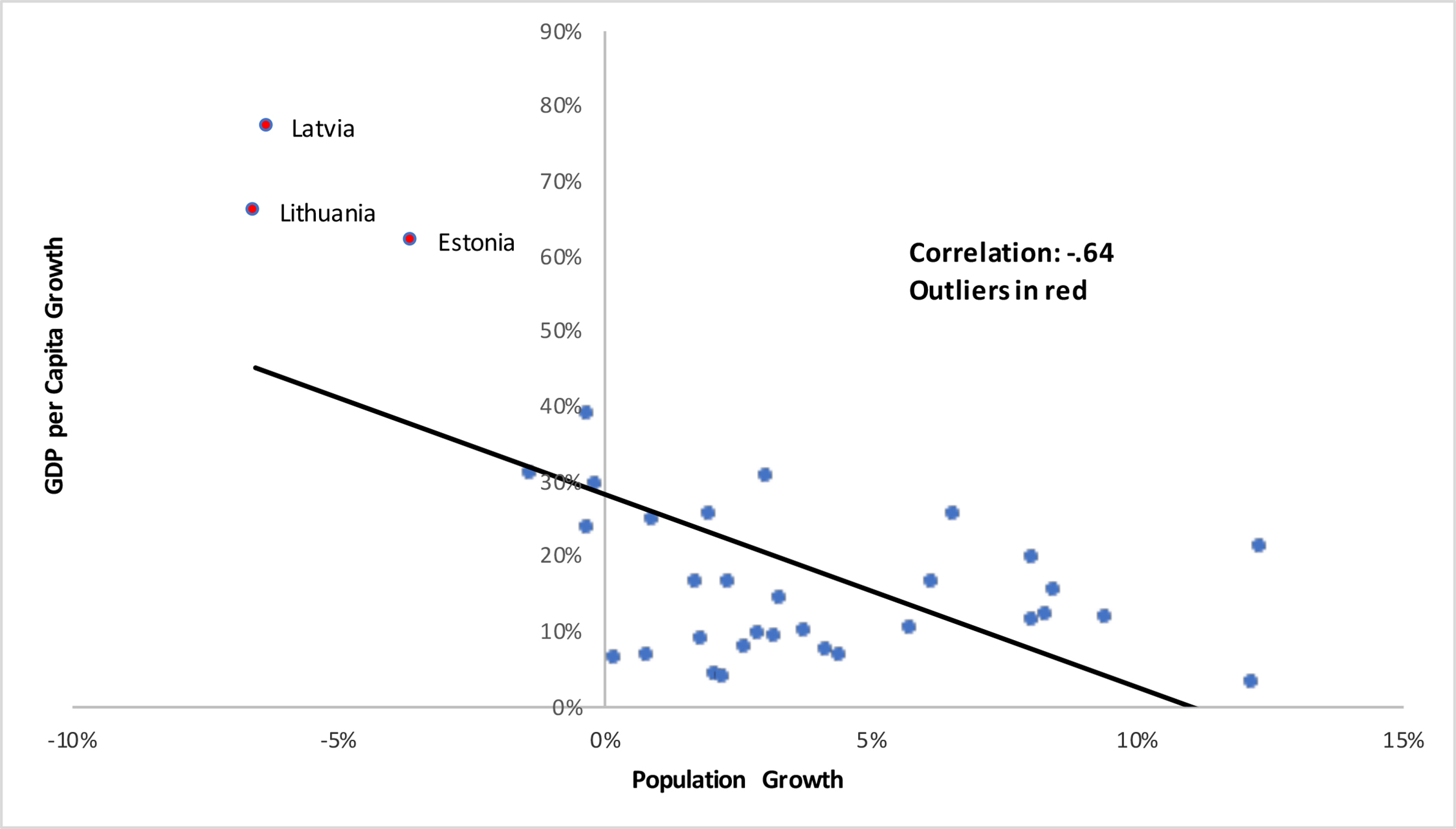

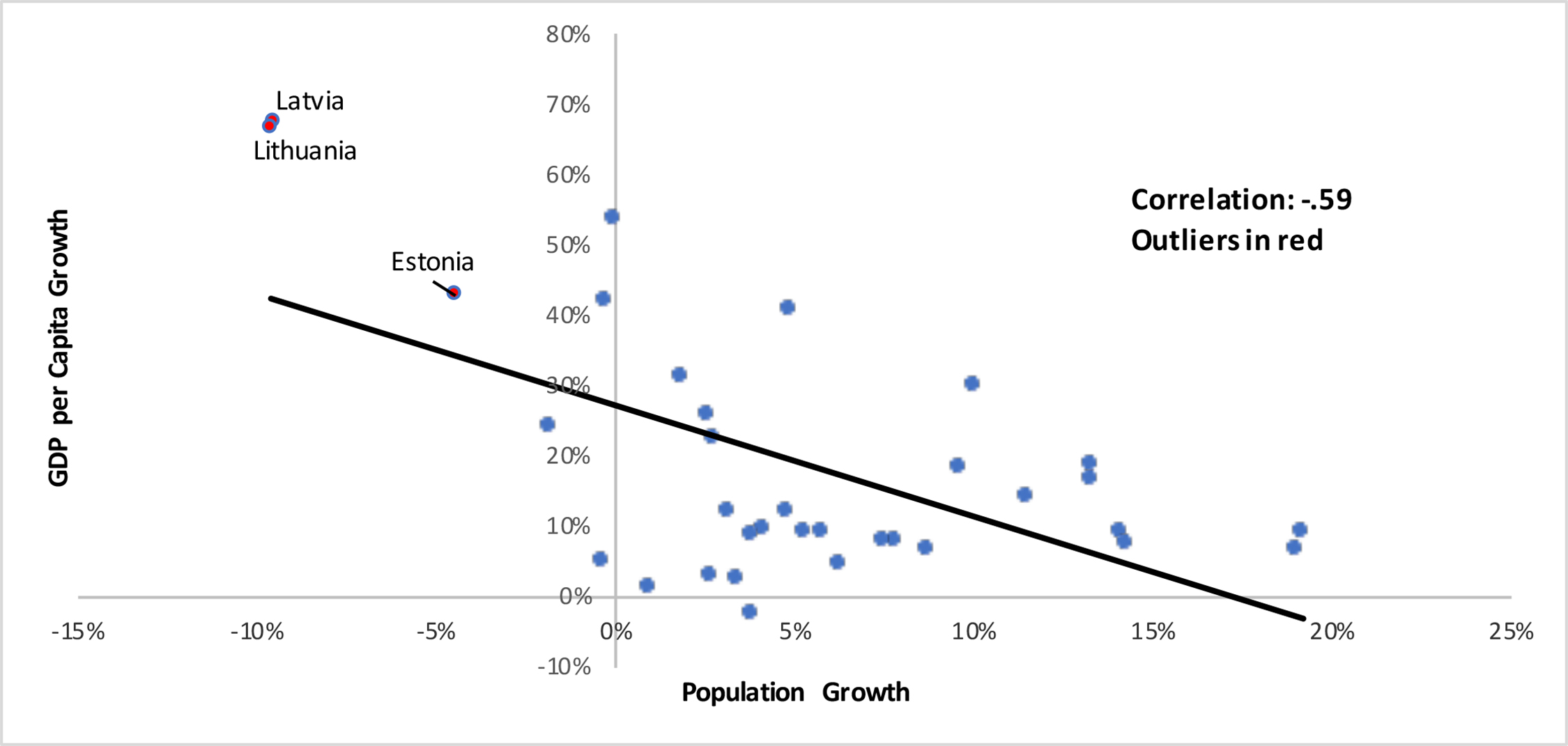

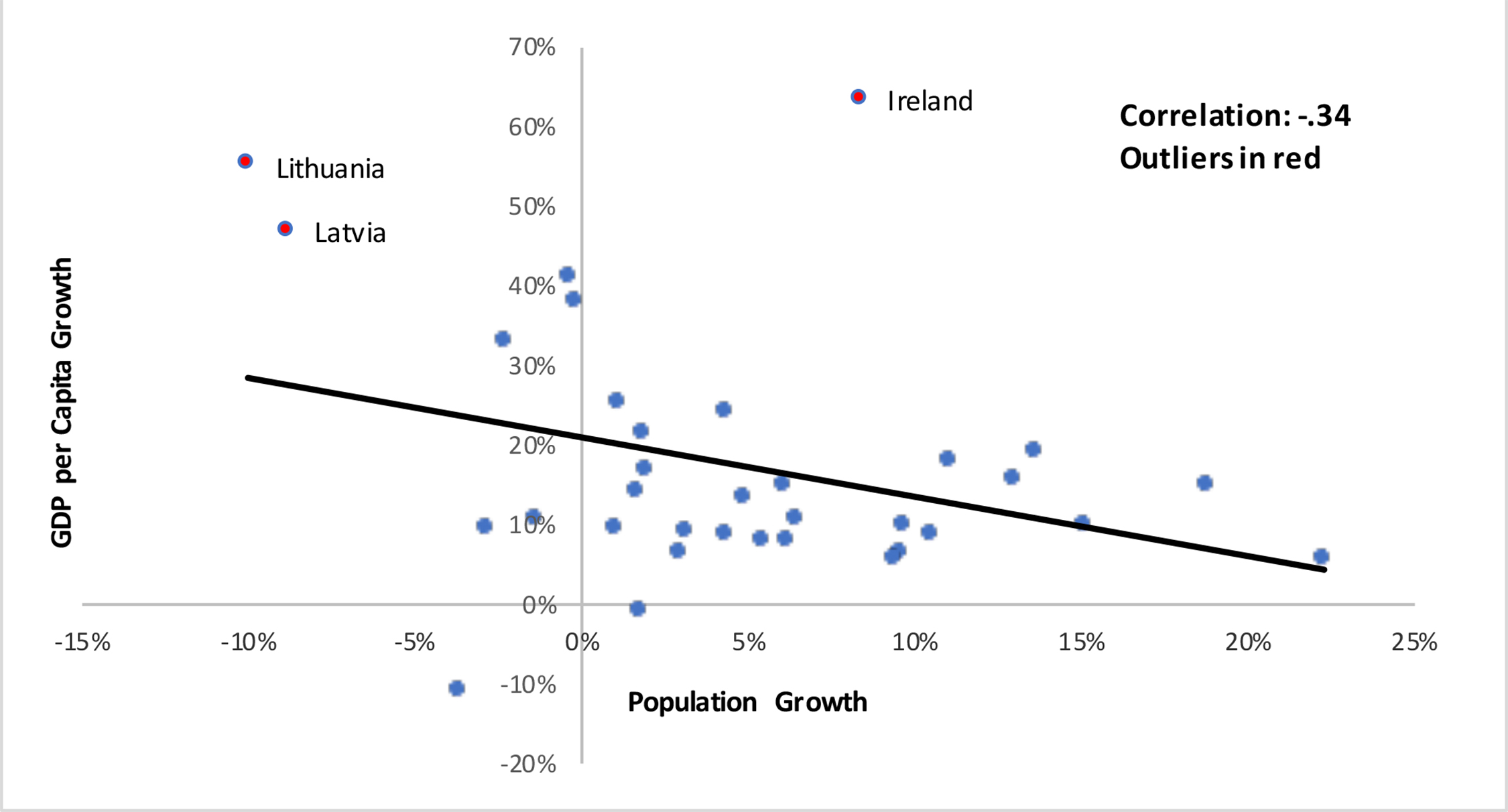

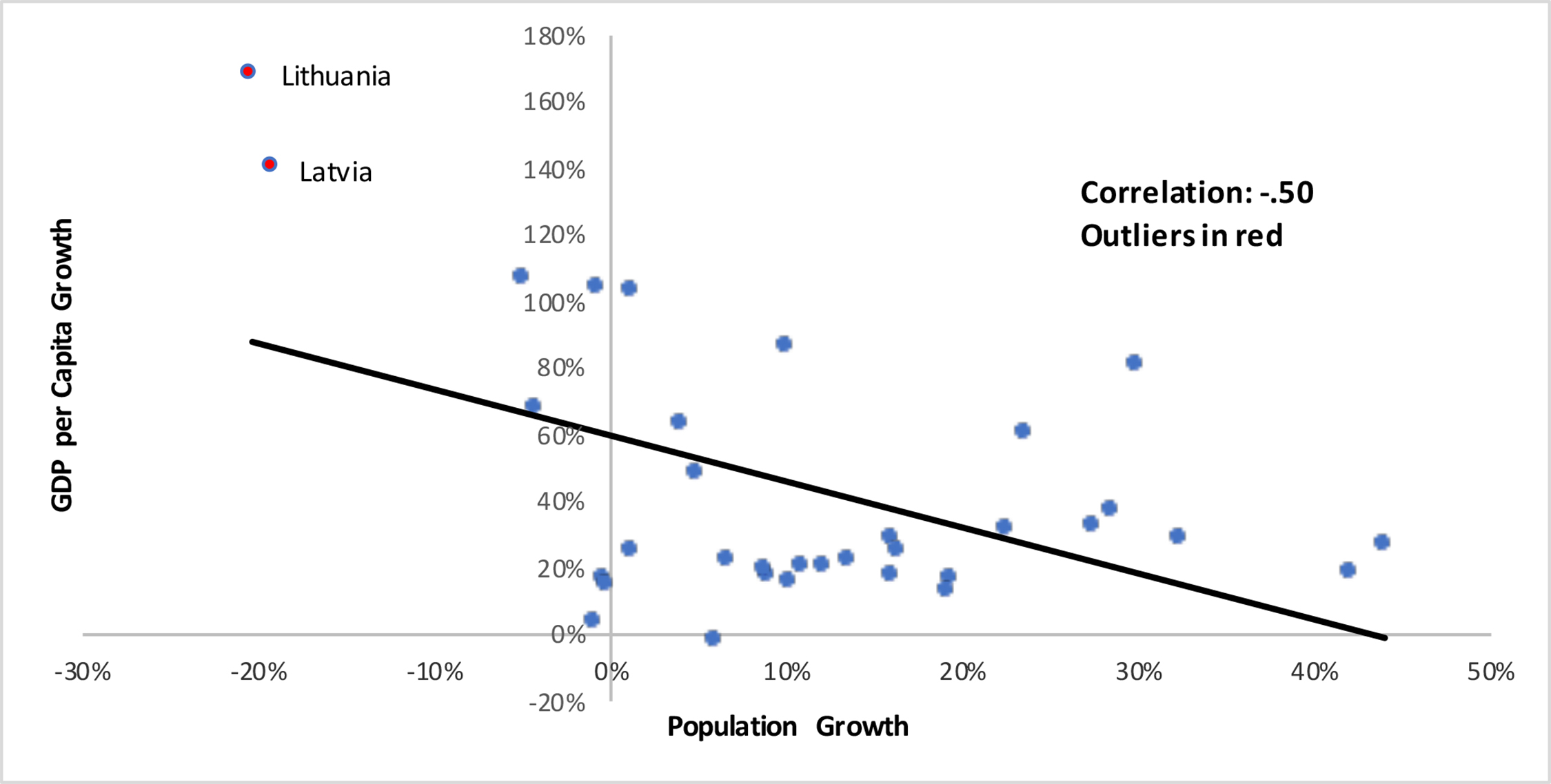

The scatter plots below show the relationship between population growth and per capita GDP growth over the last two decades. Because of the Great Recession that began in 2007, we report the correlations from 2000 to 2006 and for 2000 to 2009. We also report the relationship for 2010 to 2019 and for the entire period 2000 to 2019. All of the slopes in the scatter plots are downward sloping, indicating that countries with more population growth had less per capita economic growth than countries with less population growth. In all four time periods examined, population is not associated with economic growth.

Table 1 shows that all of the correlations are negative. Again, this means that population growth is associated with lower rates of per capita economic growth and slower rates of population growth are associated with more per capita economic growth. It should be obvious that many different factors determine the rate of economic growth in the country, and a simple correlation in no way controls for them. But our correlations are consistent with the possibility that more rapid population growth tends to slow per capita economic growth in developed countries, perhaps for the reasons outlined by Lee and Mason. At the very least, there is no evidence that higher rates of population growth result in higher rates of per capita economic growth in the way that so many population boosters seem to imagine.

Table 1. Correlations Between Population

|

||||

| 2000- 2006 |

2000- 2009 |

2010- 2019 |

2000- 2019 |

|

| Correlation Between Population Growth and per Capita GDP Growth |

-0.64 | -0.59 | -0.34 | -0.50 |

| Correlation Between Population Growth and per Capita GDP Growth (Excluding Outliers) |

-0.27 | -0.27 | -0.17 | -0.22 |

|

Source: World Bank population and per capita GDP figures in constant |

||||

In any correlation, outliers can exert significant influence on the data. The second row in the table shows the correlation if we exclude outliers, which are shown in red in the scatter plots below. These are mainly the Baltic countries, where the population has declined significantly, but economic growth is quite strong. Without the outliers, the size of the correlations is a good deal smaller, but remains negative for all four time periods, so the basic finding holds even when these countries are excluded. Of course, there is no obvious reason to exclude them as they are OECD countries with high incomes as defined by the World Bank.

It is worth adding that arguments for more population growth may be heard more sympathetically by many Americans who think of slow population growth or population decline as inherently undesirable because it is often associated with cities where problems like crime, chronic unemployment, and poor public services are pronounced (e.g. Detroit). But in such places the falloff in population is a symptom of social problems, as people fled the city; it is not the cause of the problems. Moreover, the United States is not in any “danger” of population decline. Even under the Census Bureau’s “low immigration” scenario, the U.S. population is projected to be 376 million in 2060 — 43 million more than today. In short, the depopulation of struggling American cities is in no way analogous to slowing population growth in the United States.

The chief justification for advocates who want to spur population growth, including through increased immigration, is that doing so is vital to maintaining robust economic growth. In truth, there is no clear link between the two. More people will generally make for a larger economy, but it is per capita GDP, not aggregate GDP, that determines the standard of living in the country. Prior research and the results presented here show that population growth may actually reduce per capita economic growth in developed countries. This should give pause to anyone who is convinced that slowing population growth in the United States necessarily “portends a population disaster”.

Figure 1. Scatter Plot of Population Growth and per Capita Economic Growth in Developed Countries, 2000-2006 |

|

|

Source: World Bank population and per capita GDP figures in constant 2010 U.S. dollars for OECD high-income countries. |

Figure 2. Scatter Plot of Population Growth and per Capita Economic Growth in Developed Countries, 2000-2009 |

|

|

Source: World Bank population and per capita GDP figures in constant 2010 U.S. dollars for OECD high-income countries. |

Figure 3. Scatter Plot of Population Growth and per Capita Economic Growth in Developed Countries, 2010 to 2019 |

|

|

Source: World Bank population and per capita GDP figures in constant 2010 U.S. dollars for OECD high-income countries. |

Figure 4. Scatter Plot of Population Growth and per Capita Economic Growth in Developed Countries, 2000-2019 |

|

|

Source: World Bank population and per capita GDP figures in constant 2010 U.S. dollars for OECD high-income countries. |

Table 2. Percent Population Growth

|

|||||||||

| GDP per Capita Growth

|

Population Growth

|

||||||||

| Country Name |

2000- 2006 |

2000- 2009 |

2010- 2019 |

2000- 2019 |

2000- 2006 |

2000- 2009 |

2010- 2019 |

2000- 2019 |

|

| Luxembourg | 12.3% | 9.1% | 5.8% | 18.8% | 8.3% | 14.1% | 22.3% | 42.1% | |

| Israel | 3.0% | 6.7% | 14.9% | 27.2% | 12.2% | 19.0% | 18.8% | 44.0% | |

| Australia | 11.5% | 16.8% | 9.9% | 29.0% | 8.1% | 13.3% | 15.1% | 32.4% | |

| Iceland | 19.7% | 18.8% | 19.3% | 37.0% | 8.0% | 13.3% | 13.6% | 28.5% | |

| New Zealand | 15.4% | 14.3% | 15.7% | 32.8% | 8.5% | 11.5% | 13.0% | 27.5% | |

| Chile | 25.4% | 29.8% | 17.8% | 60.2% | 6.6% | 10.1% | 11.1% | 23.5% | |

| Canada | 16.6% | 18.3% | 8.7% | 31.1% | 6.1% | 9.6% | 10.5% | 22.5% | |

| Sweden | 16.4% | 12.0% | 9.7% | 29.1% | 2.3% | 4.8% | 9.7% | 15.9% | |

| Switzerland | 7.4% | 7.9% | 6.4% | 17.1% | 4.2% | 7.8% | 9.6% | 19.4% | |

| Norway | 10.0% | 8.0% | 5.5% | 13.4% | 3.8% | 7.5% | 9.4% | 19.1% | |

| Ireland | 21.2% | 9.1% | 63.6% | 80.7% | 12.3% | 19.2% | 8.4% | 29.9% | |

| United Kingdom |

14.4% | 9.3% | 10.8% | 22.5% | 3.3% | 5.7% | 6.5% | 13.5% | |

| Austria | 9.4% | 9.8% | 7.9% | 20.4% | 3.2% | 4.1% | 6.1% | 10.8% | |

| United States | 10.5% | 6.5% | 15.0% | 24.7% | 5.7% | 8.7% | 6.1% | 16.3% | |

| Belgium | 9.7% | 9.4% | 7.9% | 20.3% | 2.9% | 5.3% | 5.4% | 12.0% | |

| Denmark | 9.0% | 2.5% | 13.4% | 17.9% | 1.8% | 3.4% | 4.9% | 9.0% | |

| Korea, Rep. | 30.6% | 40.9% | 24.2% | 86.0% | 3.0% | 4.9% | 4.3% | 10.0% | |

| Netherlands | 7.7% | 8.8% | 8.9% | 19.5% | 2.6% | 3.8% | 4.3% | 8.8% | |

| France | 6.6% | 4.6% | 9.1% | 15.7% | 4.4% | 6.2% | 3.1% | 10.1% | |

| Finland | 16.3% | 12.0% | 6.3% | 22.3% | 1.7% | 3.1% | 2.9% | 6.6% | |

| Slovenia | 24.9% | 25.8% | 16.7% | 48.1% | 0.9% | 2.6% | 1.9% | 5.0% | |

| Czech Republic |

29.5% | 31.3% | 21.6% | 63.0% | -0.2% | 1.8% | 1.9% | 4.0% | |

| Italy | 4.3% | -2.3% | -0.9% | -1.8% | 2.1% | 3.8% | 1.7% | 5.9% | |

| Germany | 6.4% | 4.9% | 14.2% | 25.1% | 0.2% | -0.4% | 1.7% | 1.1% | |

| Slovak Republic |

39.1% | 53.4% | 25.4% | 103.5% | -0.3% | 0.0% | 1.2% | 1.2% | |

| Spain | 11.8% | 7.7% | 9.5% | 17.5% | 9.4% | 14.3% | 1.1% | 16.0% | |

| Poland | 23.7% | 41.9% | 38.0% | 103.7% | -0.3% | -0.3% | -0.2% | -0.8% | |

| Estonia | 62.0% | 42.8% | 41.0% | 107.3% | -3.6% | -4.5% | -0.4% | -5.0% | |

| Japan | 6.7% | 1.3% | 10.5% | 16.6% | 0.8% | 0.9% | -1.4% | -0.5% | |

| Hungary | 30.8% | 24.2% | 33.2% | 67.7% | -1.4% | -1.8% | -2.3% | -4.3% | |

| Portugal | 3.8% | 2.9% | 9.6% | 14.7% | 2.3% | 2.7% | -2.9% | -0.2% | |

| Greece | 25.4% | 22.5% | -10.7% | 3.2% | 2.0% | 2.8% | -3.6% | -0.8% | |

| Latvia | 77.3% | 67.5% | 46.9% | 140.1% | -6.3% | -9.5% | -8.8% | -19.2% | |

| Lithuania | 65.9% | 66.6% | 55.2% | 168.4% | -6.6% | -9.6% | -10.0% | -20.4% | |

|

Source: World Bank population and per capita GDP figures in constant 2010 U.S. |

|||||||||