The U.S. government is running out of money, as a continuing resolution (CR) temporarily funding federal operations — passed on September 30 — is due to expire on December 16. Republicans will take over control of the House in January, and many in the GOP are calling for a short-term CR in lieu of a full-year “omnibus” budget that will give the party more control over spending in FY 2023. While all that’s going on, the White House wants billions to paper over its border disaster, which has no end in sight.

“Power of the Purse”. The Founding Fathers laid out a map Congress still follows in funding the federal government, and gave the House of Representatives an outsized role in the process.

Among Congress’ enumerated powers in Article I, section 8, clause 1 of the U.S. Constitution is the “Power To lay and collect Taxes, Duties, Imposts and Excises, to pay the Debts and provide for the common Defence and general Welfare of the United States”, commonly known as the “Spending Clause”.

Then, there is Article I, section 8, clause 7, which states, in part: “No Money shall be drawn from the Treasury, but in Consequence of Appropriations made by Law”. Thus, even if the executive branch has some extra cash lying around, it cannot spend it except in accordance with appropriations made by Congress.

Next is the “origination clause” in Article I, section 7. It provides: “All Bills for raising Revenue shall originate in the House of Representatives”. That has been interpreted to mean that all spending bills must arise in the House, as well, and it’s not for nothing that James Madison wrote in Federalist No. 58:

The House of Representatives cannot only refuse, but they alone can propose, the supplies requisite for the support of government. They, in a word, hold the purse. ... This power over the purse may, in fact, be regarded as the most complete and effectual weapon with which any constitution can arm the immediate representatives of the people, for obtaining a redress of every grievance, and for carrying into effect every just and salutary measure.

Budget Process, in Brief. The budget process begins when the president sends a budget request for the next fiscal year to Congress, which is supposed to be due on the first Monday in February.

Congress then drafts a budget resolution (passed by both Houses but not sent to the president for signature), setting forth the parameters of its spending plan. This process is supposed to be completed by April 15, but that does not always happen. That budget resolution includes what is known as a “302(a) allocation”, which is an overall cap on discretionary spending.

Thereafter, the appropriations committees in the House and Senate start work on funding the government. There are 12 separate subcommittees in the two chambers, each of which has “responsibility for developing one regular annual appropriations bill to provide funding for departments and activities within its jurisdiction”.

They are supposed to pass their individual appropriations bills by October 1, but that rarely happens. Usually (of late) appropriations are rolled into one large bill (an Omnibus) or into a CR to keep the cash spigot on.

Current Funding and the Administration’s “Assumptions”. Which brings me to the current funding cycle. Congress hasn’t passed its appropriations bills and is scrambling to avoid a federal shutdown when the current CR expires on December 16. Politico reports that key leaders in the two parties “are still tens of billions of dollars apart on a total amount for domestic programs”.

“Without a deal”, the outlet explains, “congressional leaders have warned that federal agencies could be saddled with stagnant budgets for the better part of 2023, an outcome that Pentagon leaders have said would be devastating for military readiness and U.S. assistance to Ukraine.”

Concerned that budgets will be flat for the current fiscal year (FY 2023), the White House sent its “FY 2023 Full-Year Continuing Resolution Assumptions” to the Hill on December 5.

The current CR includes $1.383 billion for what it terms “Southwest Border Management”, providing “operations and support” for ICE and CBP and “federal assistance” for the Federal Emergency Management Agency (FEMA).

The White House asserts that it will need a whopping $4.865 billion for these programs, or $3.482 billion over what the current CR provides. The justification for that request explains:

DHS requires additional funding in FY 2023 for management of the southwest border. Funding would be required for CBP border processing ($2 billion), ICE transportation, removal, detention, and Alternatives to Detention ($2 billion), and FEMA Emergency Food and Shelter — Humanitarian grants ($820 million).

CBP Border Processing. There is a lot to unpack there, but I will start with CBP’s “border processing” request.

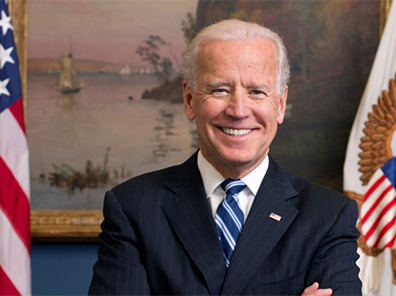

Joe Biden inherited what his first Border Patrol chief, Rodney Scott, described in a September 2021 letter to Senate leadership as “arguably the most effective border security in” U.S. history.

Scott complained, however, that Biden quickly allowed things at the border to “disintegrate” as “inexperienced political appointees” ignored “common sense border security recommendations from experienced career professionals”.

The former chief did not go into detail about what those “recommendations” entailed, but Biden quickly ended most of the successful border policies that his predecessor had put into place to bring control to the border.

Most importantly, the new president first suspended and then allowed his DHS secretary to end (twice) the Migrant Protection Protocols (MPP), better known as “Remain in Mexico”.

MPP allowed DHS to return non-Mexican aliens who had entered the United States illegally back across the border to await hearings on their asylum claims.

An October 2019 DHS assessment of the program determined that Remain in Mexico was “an indispensable tool in addressing the ongoing crisis at the southern border and restoring integrity to the immigration system”, particularly as related to alien families. Asylum cases were expedited under the program, and MPP removed incentives for aliens to make weak or bogus claims when apprehended.

Then-candidate Joe Biden derided MPP during his 2020 presidential campaign, and his administration has been fighting an effort by state plaintiffs in federal court since April 2021 to force DHS to reinstate the program — thus far successfully, albeit largely on technical grounds.

Keep in mind that a month before taking office, Biden had promised to reverse those Trump policies but averred that he would do so “at a slower pace than he initially promised, to avoid winding up with ‘2 million people on our border’” and only after erecting “guardrails” to prevent a border surge.

No such guardrails were ever implemented. Consequently, Border Patrol agents have been facing a human tsunami at the Southwest border since Biden took office, setting new yearly records for apprehensions there in FY 2021 (when they stopped nearly 1.66 million illegal entrants), and again in FY 2022, as apprehensions soared past 2.2 million.

That has left agents stuck transporting, processing, and caring for aliens who have surrendered in droves in the (reasonable) expectation they will be released, and thus rendered Border Patrol unable to stop a flood of drugs and other illegal entrants who have no intention of getting caught.

How bad is that problem? In FY 2021, there were an estimated 389,000 “got-aways”, illegal migrants who successfully evaded agents and made their way into the United States, as well as an additional 599,000 in FY 2022. Fox News reports that there have been 137,000 got-aways in just the first two months of FY 2023, including a record number (73,000-plus) in November alone.

That’s unsustainable, but note that the White House’s CR assumptions only talk about CBP “processing” those aliens, not removing them.

That’s because, as I have explained elsewhere, the administration has largely refused to use the most important tool Congress gave DHS — expedited removal — to quickly remove aliens who have entered illegally. Instead, its fallback position is to release those aliens into the United States, where they will remain indefinitely, if not forever.

Biden did, however, keep one quasi-border policy implemented by the Trump administration: expulsion of illegal entrants pursuant to CDC orders issued under Title 42 of the U.S. Code in response to the Covid-19 pandemic.

Even then, however, Biden attempted to end Title 42 on May 23, despite DHS warnings that up to 18,000 aliens would cross the Southwest border illegally per day once Title 42 ended, up from an already unsustainable average of just over 6,045 per day in FY 2022.

The administration was stymied in that effort by a federal judge who enjoined the end of Title 42 in an order issued on May 20, but unfortunately (for those interested in national security or sovereignty) a separate federal judge in November ordered the government to end Title 42 on December 21.

Given that, the Biden administration should be reconsidering those Trump border policies, but it’s not, instead asking Congress in the CR for $2 billion for CBP “processing” of illegal entrants.

ICE Funding. As noted, the White House is also asking Congress to give ICE $2 billon for “transportation, removal, detention, and Alternatives to Detention” to deal with the disaster Biden has created at the Southwest border.

Notably, the administration fails to explain how much of that funding would go to detention or removal. In section 235 of the Immigration and Nationality Act (INA), Congress mandates that DHS detain all illegal entrants, from the point they are apprehended until they are either granted asylum or removed. Given that, additional funding for detention and removal to extricate the country from this mess is appropriate.

The Biden administration has largely ignored that detention mandate, however, releasing into the United States (by my estimates) more than 1.5 million aliens who were apprehended at the Southwest border, and more than 89,000 in October alone.

Why has Congress mandated that such “arriving aliens” be detained? As DHS explained in its October 2019 MPP assessment, aliens use non-meritorious asylum claims as a “free ticket into the United States”, and once Remain in Mexico denied them immediate entry, they began to go home.

The same is true of detention. It keeps aliens safe and provides for their needs while they make their way through the asylum system, but it also denies them the ability to live and work here until they are actually granted asylum.

Despite those facts, and even though it’s facing a massive wave of illegal entrants, the Biden administration has allowed ICE detention spaces to sit empty while asking Congress to cut the number of detention beds the agency has available to it in the president’s FY 2023 budget request.

In lieu of real detention, Biden has been opting instead for so-called Alternatives to Detention (ATD). Not only does ATD have no foundation in the INA, it doesn’t work and it’s more costly than detention itself.

Here’s the rub: In Supreme Court arguments on November 29 in U.S. v. Texas — a suit brought by states challenging administration “guidelines” that contravene congressional arrest and detention mandates for criminal aliens — the government argued it lacks detention space to comply with Congress’ directives, essentially blaming Congress for not giving it money.

Disingenuously, however, the administration is now seeking money for ATD, a program under which — by definition — aliens would not be detained. The justices will rule in Texas strictly on the law, but if I were them, I would be plenty steamed by this glaring incongruity.

It’s no wonder that Speaker-presumptive Kevin McCarthy (R-Calif.) wants budget negotiators to hold off on full-year funding until the GOP takes the House budget reins in January.

FEMA Emergency Food and Shelter — Humanitarian Funding. Which brings me to the third item: the White House’s request for $820 million for FEMA’s Emergency Food and Shelter Program — Humanitarian (EFSP-H).

In September, I explained that ESFP began as a Reagan-administration program to help homeless vets, the elderly, and the handicapped, but has now transmogrified into a grant program (ESFP-H) to private and governmental organizations that feed, shelter, and transport illegal migrants released by DHS at the border.

When I wrote that, the Biden administration was “just” asking for $154 million for ESFP-H in FY 2023, but as the humanitarian border disaster it created has spun even further out of control, it now wants five times that amount, or about $122 million more than the total budgetary resources of the U.S. Export-Import Bank.

Democratic mayors have complained of late about efforts by the Republican governors of Texas and Arizona to bus a few thousand migrants released by DHS in those states to their “sanctuary” cities, but this request shows how misplaced such grumblings have been.

The Biden administration has transported many times the number of aliens that those governors have, and if the president’s request for $820 million in ESFP-H funding is approved, that endeavor will simply be turbocharged.

Of course, that will simply encourage even more foreign nationals to venture to the border, fed by tales of those who have gone before about the U.S. government’s accommodations and largesse.

A Better Idea. You will note that neither the Trump administration nor any presidency that preceded it ever had to go to Congress and demand billions of dollars to deal with record border surges.

That’s because every president before Biden had a policy of deterring illegal entrants, as my colleague Mark Krikorian recently explained. As he put it, “This administration ... is the first in our nation’s history to reject the very idea of deterring illegal immigration”.

Unless Biden takes steps to reduce the number of migrants entering the United States illegally by detaining them or — alternatively — returning them back across the border to await their hearings, the situation will just get worse. Until then, taxpayers better open their checkbooks because bus tickets don’t buy themselves and those migrants will be expecting a free ride — literally and metaphorically.