In a March 2 post captioned “Biden Administration Lost — Yes, Lost — Nearly 20,000 Migrant Children”, I reviewed answers Rep. Andy Biggs (R-Ariz.) had received in response to questions he raised to the Department of Health and Human Services (HHS) about unaccompanied alien children (UACs) — alien minors who entered illegally and who have been released to sponsors in this country. HHS’s response suggests the Biden administration, in a rush to release UACs, is endangering migrant kids.

HHS’s Role in “Sheltering” and Releasing Unaccompanied Alien Children. As I explained in that earlier post, since 2003 the Office of Refugee Resettlement (ORR) in HHS has had responsibility for “sheltering” UACs apprehended by ICE and CBP. And since 2008, the Immigration and Nationality Act (INA) has favored the release of UACs from “non-contiguous countries” (i.e., other than Canada and Mexico) to “sponsors” in the United States.

You would expect that the federal government would take great care to place alien children in safe homes and regularly check in with sponsors to whom those children have been released to ensure the kids’ well-being. Such expectations, however, would be misplaced.

In 2019, the Senate Homeland Security and Governmental Affairs Committee (HSGAC) revealed that the vast majority of UACs are released to sponsors who themselves have no status in the United States. And as my colleague Jessica Vaughan reported in 2015, some of those UACs have been released to child molesters, abusers, and traffickers.

The Trump administration attempted to curb such unforced errors, including by requiring HHS to provide information on sponsors to DHS. Consequently, the time that UACs spent in ORR care while proper sponsors were located was 102 days in FY 2020.

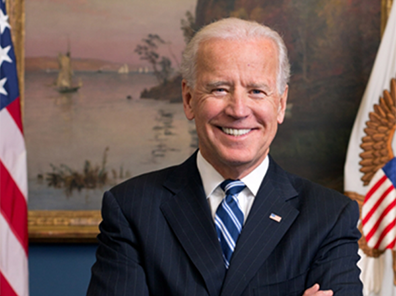

Biden Excoriates Trump Over Child Detention. Then-candidate Joe Biden excoriated Trump over UAC detentions, stating in the second sentence of his campaign website’s lengthy immigration page: “It is a moral failing and a national shame when ... children are locked away in overcrowded detention centers and the government seeks to keep them there indefinitely.”

As a result, there were a number of changes in the processes by which ORR releases unaccompanied children after Biden took office, even as the number of UACs apprehended at the Southwest border skyrocketed under his watch.

The new administration revoked the information-sharing agreement between HHS and DHS, and most significantly, as the Congressional Research Service has explained, ORR under Biden “has temporarily waived background check requirements for household members living with prospective sponsors and authorized its shelter operators to pay for some children’s transportation costs.”

Not surprisingly, the amount of time children spent in ORR custody plummeted, falling to 35 days in the first six months of FY 2021, a period that dropped to 30 days by the end of December.

To Whom Does HHS Release Unaccompanied Alien Children? “Quicker” does not always mean “better”, and there are some real danger signs in the response that Biggs received from HHS, which the congressman tweeted out:

Additional details from HHS ?? pic.twitter.com/BOssFTG32v

— Rep Andy Biggs (@RepAndyBiggsAZ) March 1, 2022

Many UACs are placed with their own parents in the United States. Then-DHS Secretary John Kelly revealed in a February 2017 memorandum that 60 percent of UACs who had been released in the prior three years went to live with parents illegally present here. And Kelly complained that many of those children “travel[led] overland to the southern border with the assistance of a smuggler who is paid several thousand dollars by one or both parents”.

That does not mean that UACs whose parents are not in the United States remain in HHS custody, however. Rather, ORR breaks potential sponsors into four categories, with two subcategories, as follows:

Category 1: Parent or legal guardian. This includes qualifying step-parents that have legal or joint custody of the child or teen.

Category 2A: A brother; sister; grandparent or other immediate relatives (e.g., aunt, uncle, first cousin) who previously served as the UC’s primary caregiver. This includes biological relatives, relatives through legal marriage, and half-siblings.

Category 2B: An immediate relative (e.g., aunt, uncle, first cousin who was not previously the UC’s primary caregiver. This includes biological relatives, relatives through legal marriage.

Category 3: Other sponsor, such as distant relatives and unrelated adult individuals.

Category 4: No sponsor identified.

Interestingly, HHS told Biggs that of the 146,248 UACs ORR placed with sponsors in the United States between January 20, 2021, and February 7, 2022, 62.3 percent were released to Category 2 and 3 sponsors, that is, people who were not the child’s parents.

That said, let’s start with the child’s own parents. Those individuals have been in the United States for an indefinite period that the child has been living back home, and there is no guarantee that there is an actual relationship — aside from sanguinity — between the child and the parent.

That goes double for a child’s “guardians”. The whole idea of being a “guardian” is that one is present for a child. If the guardian has been here, however, while the child has been hundreds — if not thousands — of miles away, it is questionable whether the guardian has been filling such role.

Taking that thought one step further, how exactly would a sibling, grandparent, aunt, uncle, or first cousin be a “primary caregiver” to a child who lives abroad for purposes of Category 2A at any point in the recent past?

If my aunt babysat my son a decade ago when he was of tender years, does she count as a person who was a “primary caregiver” for him in the past? ORR seemingly elides even this fine point in categories 2A and 2B.

Nor does a blood relationship (let alone a relationship based solely on affinity) guarantee that a sponsor has any interest in the well-being of a child. That is not to say that there are not plenty of extended relatives who are kind and loving caregivers, but many of those individuals are little more than strangers having family ties in common with the child.

Then, there is Category 3.

As HHS states in its response to Biggs: “For unrelated adults, it is common among the UC population [“unaccompanied child”; Biden forbade the executive branch from using the word “alien”, even though “unaccompanied alien child” is defined in statute] for these potential sponsors to include fictive kin such as godparents or close family friends who, while not related to the UC by birth or marriage, have an emotionally significant relationship with the child.”

I consider myself a well-read and educated individual, but “fictive” was a new word for me (this is not the first time Biden administration immigration policies have sent me to the dictionary). Here is how Merriam Webster defines the term: “1: not genuine : FEIGNED; 2: of, relating to, or capable of imaginative creation; 3: of, relating to, or having the characteristics of fiction : FICTIONAL”.

That may be a little harsh, as I likely have a “fictive” association (as HHS appears to be using the word) with any number of friends’ kids. Mine is an “avuncular” relationship with those children, although we share neither name nor blood.

Of course, I am around those children regularly, a fact that would appear to not be true as it relates to those Category 3 sponsors, who have been living in a different country for an indefinite period.

And other people’s children are not like a car or a stamp collection that someone else has bequeathed to you. They require constant attention and care. How many “fictive kin” are up to the task, really?

And, as for the “UC population”, I assume HHS is referring to UACs from Central America and societal norms therein, but that does not account for the more than 7,000 UACs CBP encountered at the Southwest border in FY 2021 who were neither Mexican nationals nor from El Salvador, Guatemala, or Honduras.

Potential Risks to Unaccompanied Alien Children. The bigger problem, however, has to do with how ORR by its own admission is screening potential sponsors.

HHS explains that it runs a public records and sex-offender registry check on all sponsors, but the department makes clear that it does not require fingerprints “for Category 1 and 2 sponsors who meet eligible criteria” (whatever that means) and does not even do the background check for other adults living in a sponsor’s house unless it is “appropriate” — based on criteria that HHS fails to share.

As an INS prosecutor and an immigration judge, I dealt with any number of cases in which abuse — both physical and sexual — was inflicted on a child by a parent or extended relative or family “friend” living in the child’s household. Background checks are often flawed or inconclusive, and sex registries only contain information on individuals who had the means or opportunity in the past to prey on victims and who have been forced to register, usually because they were caught and convicted.

Fingerprint checks, on the other hand, are a much more reliable method of determining whether an individual (or a family or other household member) has been arrested for a crime and/or has been convicted. Such checks are not difficult for either the potential sponsor or the agency to complete and should be the baseline for any release decision involving a child.

Note further that it’s not even clear from its response that HHS mandates fingerprint checks for all Category 3 sponsors.

Worse, the department states: “ORR still requires a fingerprint check on sponsors where the public records check reveals possibly disqualifying sponsor criteria; there is a documented risk to the safety of the child; or the child is especially vulnerable and/or the case is being referred for a home study.”

Consider that statement. Why, exactly, would ORR continue to think about releasing a child where “the public records check reveals possibly disqualifying sponsor criteria” or where “there is a documented risk to the safety of the child”?

More saliently, however, that statement reveals ORR runs fingerprint checks in cases where the background and registry checks reveal derogatory information to see whether the child could still be placed with a potential sponsor for whom it has discovered such information, not to verify that the child should not be so placed.

The Biden Administration Should Be Discouraging Minors from Entering Illegally. Given the volume of UACs with whom the Biden administration is dealing (CBP has encountered more than 175,000 unaccompanied alien children at the Southwest border since February 2021), one could understand the president’s dilemma in dealing with the flow.

These are children, however, and so expediency should not be a factor in their releases. Detention in an ORR shelter may not seem like it is in the “best interest of the child”, but it is when the alternative is a risk of sexual or physical abuse, trafficking, or neglect with an unfit (or worse) sponsor in the United States.

Biden should do what his old boss, President Obama did, when he was faced with a surge in UACs in June 2014: Ask Congress to amend the 2008 law that encourages those children from “non-contiguous” countries to enter illegally by all-but-mandating their release to sponsors in the United States.

The law in question, the Trafficking Victims Protection Reauthorization Act of 2008 (TVPRA, which was passed well into FY 2009) is the main pull factor that encourages children to enter the United States illegally. More specifically, it encourages their smugglers and family members to bring them here, in the knowledge that almost all will be released.

Want proof? The Administration for Children and Families (ACF), the HHS component overseeing ORR, explains that: “For the first nine years of the UC Program at ORR, fewer than 8,000 children were served annually.” Again, ORR gained jurisdiction over UACs in 2003, so the time period in question is between FY 2003 and FY 2011.

ACF continues: “Since Fiscal Year 2012 (October 1, 2011 – September 30, 2012), this number has jumped dramatically.” Has it ever. Since smugglers discovered the TVPRA loophole, the number of UACs has surged, with DHS referring 13,625 children to ORR by the end in FY 2012; 24,668 in FY 2013; 57,496 in FY 2014; 33,726 in FY 2015; 59,170 in FY 2016; 40,810 in FY 2017, 69,488 in FY 2019; and 15,381 in FY 2020.

Even by historical standards, however, Biden’s own campaign rhetoric has turbocharged UAC illegal entries. In FY 2021, DHS referred an eye-popping 122,731 UACs to ORR.

Further, between March 2003, when ORR was given responsibility for UACs, and the end of FY 2021 (a 19-year period), ORR has placed more than 410,000 UACs with sponsors. More than a quarter (26.3 percent, just short of 108,000) of those children were released in FY 2021 alone.

By the way, about 11 percent (nearly 11,800) of those UACs released by ORR in FY 2021 were placed with Category 3 sponsors, those “distant relatives and unrelated adults”, including “fictive kin”.

Three Options. The Biden administration has three options: (1) It can keep releasing unaccompanied alien children as it is now, at risk that some will be subject to trafficking and abuse; (2) it can thoroughly vet all potential UAC sponsors, a process that will take time and money; or (3) it can work with Congress to remove the incentives for alien children to enter illegally. Option 3 is the safest for the kids, and the best for the country.