Read the report: Growing Numbers of Cuban Migrants in the United States

Jessica Vaughan, Director of Policy Studies, Center for Immigration Studies

Kausha Luna, Research Associate, Center for Immigration Studies

Dan Cadman, Fellow, Center for Immigration Studies

www.superiortranscriptions.com

JESSICA VAUGHAN: Good morning, and welcome to this CIS teleconference. And thank you for participating.

I’m going to go a little bit slowly to begin with because I understand there may be some people having trouble calling in. But this morning we’re going to be talking about the recent surge of Cuban migrants and the larger issue of how our asylum system has evolved in recent years to the point where it is now a major way of entry not only for Cubans, but for illegal immigrants in general from a lot of different countries.

Most Americans are aware that the United States has had a unique immigration policy for Cubans since the 1960s and since the – and the advent of communism on that island, and the idea was to offer a safe haven to those Cubans who were fleeing oppression by the regime of Fidel Castro. There have been times when this special pathway has become a major migration event, both in the ’50s and ’60s, and also in the mid-’90s, when a very large number of Cubans were arriving.

Most people tend to think of Cubans fleeing Cuba by boat, and thousands do do that every year. But actually, the number of people arriving at the land ports of entry has always been much, much larger than the number arriving to the United States by boat. And not arrivals at the port of entry in Miami, but it has always been the port of entry in Laredo, Texas – at least for the last 10 years – were the majority of Cubans have arrived in the United States.

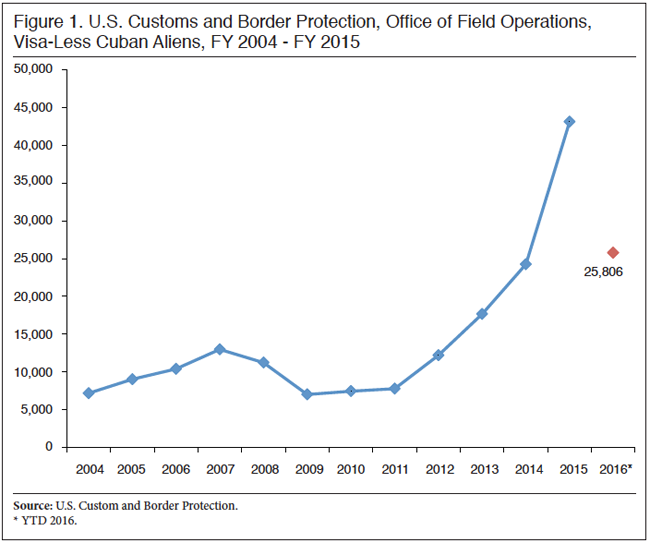

We’ve seen a significant increase in the number of arrivals in the last few years. There were about 24,000 who arrived in 2014. That went up to 43,000 who came in 2015. And so far this year, in 2016, there are already about 26,000 Cubans who’ve arrived by land.

And so we’re going to explore the reasons behind this phenomenon. My colleague Kausha Luna, who is a research associate at the Center, has been covering these land arrivals for a number of months, and she’s going to tell us the roots of this new growth in arrivals – how it has happened and how it’s – how it is taking place.

And my colleague Dan Cadman, who is a senior fellow with the Center, is going to talk about the – what in our immigration law – what our immigration law provides in the way of asylum-seekers, both in general and with respect to Cubans; how U.S. policy has evolved under the Obama administration; and also a little bit about what could be done to address this problem.

And then, afterwards, we’re going to have a question-and-answer session. And at that point, I will turn it over to my colleague Bryan Griffith, who will explain how to participate in that.

But for now, I’d like to turn the forum over to Kausha Luna.

KAUSHA LUNA: Good morning. Thank you for calling in. As my colleague Jessica explained, today I’m going to be going through a step-by-step process of Cuban migration and the general route that they’re taking, as well as some of the factors that are influencing the uptick that we’re seeing in Cuban migration through the land borders in particular.

The most common route taken by the islanders is as follows. They are flying from Cuba to Ecuador, which, prior to December 1st of last year, did not require a tourist visa. And, as such, they have been able to fly out of Cuba more readily, as well as, as of 2013, Raul Castro lifted a travel ban, which has also made it a lot easier for these migrants to leave the island.

In addition to these two policy changes abroad, the United States, as early as of 2011 under the Obama administration, lifted a series of remittance levels that can be sent to Cuba, as well as the amount of remittances licensed carriers can take to the island with them. Reports have shown that these remittance levels sent to Cuba are expected to double in 2016, and these increased levels of income can facilitate the expenses that are required to leave the island and travel to the United States via airplane, land, and as well as expenses required to be covered for smugglers to cross the various borders which they are crossing.

From Ecuador, they are crossing from Colombia into Panama, most often using smugglers. These borders are very porous, so it is relatively easy for them to use a smuggler and get from one country to the next. And from Panama, then they are able to continue their way north through Costa Rica and the rest of Central America until they reach Mexico.

Once in Mexico, the Cubans are either detained or they present themselves to the National Institute for Migration, which is the institution in Mexico which is in charge of managing migration through the country and in and out. Actually, in October, about 900 Cuban migrants in Chiapas, Mexico, which is a southern border state along the Guatemala-Mexico border – 900 Cubans, in fact, turned themselves in to the authorities for them – for them to be processed.

Once in the custody of the National Institute for Migration, or INM by its Spanish-language initials – the INM then contacts the appropriate embassy to confirm the alien’s nationality. In fact, when my colleague Jessica and I were able to visit the border, we spoke with a high-level official at INM who explained the process, and she explained that once they communicate with the appropriate embassy they allot for a 15-day period for Cuba to recognize their citizen per Mexico’s immigration law before they release the islander.

About 3.7 percent of Cubans apprehended are deported. That means the majority, once they come to INM, are released with a 20-day safe passage permit, which allows them to then regulate their stay in Mexico or, as the majority do, continue their way through Mexico to the northern border with the United States. Once the islander has been granted the safe passage permit, they are let go. And, as the official noted, none of them want to stay in Mexico, as their ultimate goal is to reach the United States.

When they reach the United States, as my colleague Jessica noted, the majority are crossing through ports of entry as opposed to attempting to cross the border illegally. And the majority, about 70 percent of them, are doing so in Laredo, Texas, through Bridge 1.

During our visit to the border, we were also able to speak with CBP officials, which then noted that the majority of Cubans are merely showing up and, in Spanish, saying “I’m here for Cuban adjustment,” making it very clear that the primary magnet is the United States’ immigration policies.

During our visit to Bridge 1, we were able to see the Cubans have their own line at the port of entry, and where they arrive and are waved in in order to be processed. Once they’re waved in, they fill out a worksheet with biographical information and get their pictures taken, as well as fingerprinted and checked for prior deportations and serious criminal history. Once they go through this process, they are generally paroled into the country, at which point the benefit of the “wet-foot, dry-foot” policy, as well as the Cuban Adjustment Act, kick in. However, during our visit, we learned that this has not always been the case, and the policy of parole has been interpreted differently across time, which my colleague Dan will speak to once I am finished.

And then, once they are paroled into the country, we are – they are welcomed by a banner directly across the bridge by an NGO called Los Cubanos en Libertad, which is an NGO that provides them guidance in order to tap into the benefits granted to these presumed refugees, which include TANF, SNAP and Medicaid.

The problem with the processes and these flows that we’re seeing is that the Cuban Adjustment Act and the accompanying “wet-foot, dry-foot” policy were intended for refugees and dealing with the flows that we were experiencing during the Cold War and under the communist regime in place at the time. But the issue now is that these migrants are generally not refugees. In fact, as we learned during our visit, these migrants are coming from all socioeconomic backgrounds, and many of them are actually professionals.

Also, they’re not all leaving from Cuba directly to the United States. Some of them, in fact, have been living in Ecuador. For instance, one Cuban we spoke to had been living in Ecuador for several years and then had flown to Mexico to come into the U.S. through Bridge 1. Also, others are living in Spain and other European countries to fly into Mexico and then cross into the border. Here we see that the policies in place are indeed not serving refugees, but are creating a magnet for an array of Cuban migrants – generally, economic migrants.

And most recently, these policies have created – have instigated a series of airlifts from Costa Rica and Panama, and have been directly flown to our border with the understanding that they will be let into the country. However, the administration has acknowledged its awareness of these airlifts, and has continuously stated that it will not be changing any of the policies in place. And of course, all of these migration flows are costing – of significant expense for American taxpayers, as when they arrive they are given a series of access to benefits.

And with that, I will turn it over to my colleague Dan.

MS. VAUGHAN: Great. Thank you, Kausha.

I just wanted to mention also to our listeners, in case you’re not aware, Kausha’s full report is on our website at https://cis.org/. And there you can also find a few reports by Dan Cadman, who’s going to speak next. Some of his are linked in our announcement of this event today.

So, Dan, I’d like to turn it over to you now for the next segment of our presentation.

DAN CADMAN: Thanks, Jessica.

Kausha has talked about the systematic nature of what’s going on at the southern land border, particularly in Laredo. And I think it’s significant to try and tie that back to the U.S. maritime policy, which people who are participating in this as listeners may recall has evolved over time, and in the early ’90s, because of the huge flow of Cuban and Haitians arriving in Southern Florida on scows, rafts, et cetera, resulted in a presidential decision directive from President Clinton at the time giving the Coast Guard a very clear migrant interdiction role. And under the terms of that migrant interdiction operation – MIO – which is ongoing to this day, the Coast Guard was directed to pick these people up in international waters, both to ensure their safety but at the same time to secure the coasts of the United States against illegal entry.

And in order to balance law enforcement with humanitarian and refugee requirements, asylum officers were assigned to those Coast Guard cutters, and I believe are to this very day, so that when people are brought onboard those cutters they are administered what’s called a credible fear test to determine whether they actually have a fear of persecution in their country of origin – and in this case we’re talking about Cubans – or whether they are, in fact, economic migrants. And if they are economic migrants, they are returned to their country of origin without being given the opportunity to set foot in the United States and trigger what we see going on at the southern land border.

And I think one of the ironies of what we’re seeing is that the United States is undercutting its own policy by allowing the Cubans an alternative path which involves them moving southward into Latin America and then through various paths – by airplane and train, bus and foot – showing up at the ports of entry and simply saying “I’m here for the Adjustment Act” and having themselves waved through almost like dropping a token in a turnstile at a subway station, and being allowed in without even going through the requirement of being put to a credible fear test.

And, as Kausha said, many, many of these individuals – probably the vast majority – are economic migrants. They are not people who have opposed the Castro regime. They are not dissidents. They are not members of Mothers in White. They are, by and large, individuals who see their circumstances changing where they’re at. For instance, in Ecuador, the economy has collapsed, and if they had been residing in Ecuador they want out. And word gets out very quickly that the United States is choosing to apply a very liberal policy by presenting themselves at the port of entry, not even requiring that they show that they are potential asylees, and simply paroling them in.

And I would note this: The Cuban Adjustment Act is only effective upon the grant of that parole. It is unique to Cubans. It doesn’t apply to other nationalities. If some other nationality were to show up at a U.S. port of entry, and Customs and Border Patrol officers were to be presented with an alien who had no visa, no permit, no reason – no rational reason or basis to enter, they would be excluded. There is no reason that that same process should not apply to these Cuban individuals because there is no requirement that they be paroled. There is nothing in the Adjustment Act that requires their parole.

The U.S. government could reasonably, to shut this flow down, say we are not going to admit you. We are going to hold you in exclusion proceedings. If you have a fear of return, you’ll be given the opportunity to explain that and justify it, and prove that you have the right to asylum. And you can wait in Mexico until the time of that hearing. And if you prove your case, then we will parole you in. And if you do not, we are going to leave you in Mexico for the Mexican authorities to deal with. If the United States government chooses another course – as it has in this case – essentially, they are condoning an organized smuggling ring involving tens of thousands of individuals.

And you have to ask yourself why the U.S. government would do that – why, by their own admission, they are cooperating closely with the Mexican authorities at INM to allow these individuals in. And it actually leads me to ask whether there isn’t some basis to believe that, quietly in the background, the Obama administration isn’t underwriting the cost of these flights. Charter flights are inordinately expensive. Most of the countries in Central America do not have the kind of funding available to afford this. And I have to believe that if the U.S. government were to put its foot down and say absolutely not, given the massive amounts of aid that flow into those countries, they would recognize that they would have to abide by the U.S. decision not to accept this state of affairs or risk that aid. But we don’t see that happening. And I cannot help but wonder whether Freedom of Information Act requests would show a different story than we are seeing in the public eye.

But suffice it to say the Cuban Adjustment Act does not require that they be paroled in. And fairness dictates that these individuals who show up with no visas, no permits be treated as any other nationality, and doing otherwise makes absolutely no sense whatsoever. And it particularly doesn’t make sense given that the United States has normalized relations with Cuba now, and should not allow itself to be held hostage to the equivalent of a Cold War relic, which is what the Adjustment Act is, and which even Marco Rubio has said should be repealed.

So that’s pretty much about what I have to say.

MS. VAUGHAN: Thank you so much, Dan.

Now I’d just like to offer a few more observations from recent trips that I’ve taken to other ports of entry as well about the magnitude of the flow of asylum-seekers that we’re experiencing.

So, as we’ve seen here, there is a detectable relationship between the number of arrivals from Cuba and U.S. policy and how we process Cubans. This is not a random migration event, a force of nature, and nor is it directly related to anything that’s going on in Cuba other than, you know, the policies they have of making it easier for people to leave.

While this phenomenon, this surge, is especially true of Cubans because we have the most lenient policy for them and they’re most assured of getting permanent status and it’s – you know, there are many incentives, including the welfare benefits that they have access to upon arrival, this phenomenon is by no means limited to Cubans alone. What I have observed at other land ports of entry, most recently San Ysidro, is that we are seeing also a major spike in asylum-seekers from other nations, as well as Cubans. The Cubans are coming to Laredo. Now some of them are being flown to El Paso from Panama. But we’re also seeing spikes of arrivals of Chinese; Indians; Ecuadorans; Venezuelans; Haitians; Brazilians into Brownsville, Texas; Eritreans into Hidalgo. And there is – there are discernable patterns that Customs and Border Protection has seen – that, you know, for example, the Brazilians go to Brownsville, the Haitians go to San Diego, the Indians go to Arizona, the Eritreans go to Hidalgo – which indicates that, you know, there are organized smuggling rings who are well aware of what U.S. policies are and what will happen to people when they arrive at the legal port of entry and claim asylum. They’re coached on what to say and they know what the result will be. And under the current administration, the result is that they will be allowed to stay and make an asylum claim.

In San Ysidro a couple of weeks ago, I saw that they have a dedicated line at the pedestrian crossing point specifically for asylum-seekers. They’re getting so many every day they no longer have enough room to keep them in detention. Their capacity is 3(00) to 400 that they can handle in detention and, you know, the line that I saw was quite long of people showing up. And there, half of the people who are coming to claim political asylum are from Mexico.

We don’t have exact numbers on exactly how many people are claiming asylum. It’s hard to pin down. But I have seen some figures from 2015. About a year ago, there were about 82,000 asylum cases that were pending in immigration court. But that’s not all of them, when you consider that only about half of them actually get to immigration court. Many of them are disposed of by USCIS asylum officers, and they received – last numbers I saw – about 7,000 a month. These cases are put into our – you know, some of them can be approved by USCIS, but many of them are allowed into the United States to wait for their immigration court hearing, which can take years.

We also know that, in 2015, there were about 50,000 work permits that were issued, not only to Cuban parolees but also other nationalities who are requesting political asylum. And I think part of the issue here is that, unlike the maritime interdiction program that Dan described where, you know, people were – you know, had the opportunity to make their claim literally onboard when they were picked up, there are no asylum officers that are posted at the ports of entry. And that means, ultimately, that many of them end up getting released into the country to await the opportunity to make a claim, or to not show up when they make that claim.

So it’s well-known now, and the smuggling organizations market the fact that if you arrive on our doorstep and claim a fear of return, no matter how dubious it might seem, that’s your ticket into the United States. And this should be of great concern, not just for the integrity of our immigration system but what – from what I’ve heard from CBP officials in various places that it’s not just economic migrants who are taking advantage of this policy, it is now, in the words of one official, the easiest way to return to the United States if you are a previously deported criminal alien is to appear at a legal port of entry with – you know, ideally with your children, and claim a fear of return to your home country. We’re starting to see an increase in the number of previously deported criminal aliens showing up and also gaming the system in the same way that the Cubans and the Eritreans and the Mexicans and the Indians are doing it – claim a fear of return. And depending on which state you enter in, you may be released depending on whether or not that state government will take custody of your children.

So, again, we don’t have any numbers on this, but hope to be able to obtain them through information requests.

So clearly our asylum system and the policies that enable people to take advantage of this route into the United States are something that ought to be high on the agenda for Congress and for all candidates for federal office, whether congressional or presidential candidates.

So let’s open it up now to questions from people on the other side of the line.

BRYAN GRIFFITH: Hi, this is Bryan Griffith. I am about to start the question-and-answer – (audio break) – I apologize for that. It muted me when I did that. In order to get in the question-and-answer queue, just press star-six and then one. That’s star-six and then the number one. And once we have people in the queue, I’ll identify you if I can by name or the last four digits of your phone number, and more importantly you should begin speaking when you hear the voice prompt that tells you that you are unmuted.

So I believe we’re going to start with someone with the last name Kirby. Please identify yourself. I could be incorrect about your name. Last name Kirby, last four digits of your phone number is 0910. I am going to unmute you.

Q: Yeah, hi. This is Brendan Kirby from LifeZette.

I was wondering if you could give us an idea of how much money in benefits the United States is paying to asylees coming in through this Cuban route.

MS. VAUGHAN: That’s a good question. It’s significant, because – but it’s different depending on whether they come from Cuba or from one of the other countries. My understanding is that it is the – specifically the Cubans and Haitians who arrive who are the only ones able to take immediate advantage of the refugee resettlement assistance, which is about $1,800, depending on how much the NGO that is assisting them takes from it for the services that they provide. But they are also immediately eligible for other social services, like Medicaid, Temporary Aid to Needy Families, and the other – the full array of benefits, you know, as if they were citizens or long-term legal public residents.

We’ve done some studies on the cost of resettling refugees through the Refugee Program, which is about 60,000 (dollars) a year. The asylees – or, excuse me, the people coming in, like Cubans and so on, are probably – you know, could – depending on how quickly they are able to get a job, could be something close to that. But I am not aware of any specific calculations, although, you know – and again, it depends on whether – you know, how quickly they are able to find work, if they are.

Q: Thanks.

MR. GRIFFITH: All right, on to the next question. Again, if other folks want to get in the queue, it’s star-six and then one. That’s star-six and then the number one.

The next question is from Bedard, 1073. I’m going to unmute you.

Q: Hey, thanks. Jess and Kausha, those numbers are pretty high, right? You’ve got more in the first two months of this year, Cubans coming into the U.S., than all of 2014.

MS. VAUGHAN: Correct.

Q: Is there – is it the opening – open doors kind of between the president and Castro that has prompted that?

MS. VAUGHAN: Kausha, do you have any thoughts on that?

MS. LUNA: Generally speaking, the president’s announcement of warmed relations between Cuba and the United States seems to have induced a fear that policies would change. However, as we mentioned in the report, there are a series of policy changes that have made it even more attractive to come to the United States and facilitated that process. But one of those factors is the warming of relations. However, I would hold that the Cuban Adjustment Act and the benefits that accompany it are the primary magnet for the increased flow.

MS. VAUGHAN: Yeah, there definitely is a sense in Cuba that, you know, they’re aware of the new relationship and that something might change.

Q: Yeah.

MS. VAUGHAN: In fact, today is the third meeting of the bilateral commission that’s been set up to talk about a variety of issues, including migration. But Cubans also know that the only route through our legal immigration system would be to have a family relationship or an employer who sponsors someone for an employment-based green card, and most Cubans, just like most people in the world, do not qualify for those legal routes. And they’re also aware that if they make it to the United States that the current policy is to allow people to enter and to receive parole and then adjust through the Cuban Adjustment Act.

But they also know this has not always been the case. I mean, until 1996 we used to send Cubans who arrived at Laredo or any other land port of entry back to Mexico City to wait there for an interview to have their asylum claim reviewed. That’s not so attractive an option because, you know, there was – there was more chance that you might be refused and you would have to hang around in Mexico for a while. And even in recent years, prior to the Obama administration, according to CBP officers that we talked to, there would – there would be interviews in which people would actually have to establish that they faced some sort of oppression in Cuba. And it might be determined through an interview that they, you know, really had not been singled out for any kind of oppression or persecution, and they would not be allowed to enter to adjust. But in recent years, it – you know, it – there has been no screening for that aspect of qualifying.

Basically all they have to show is their Cuban passport and submit fingerprints, and they are allowed in to pursue adjustment. They’re paroled in. We were told that the only people who are rejected for parole are people with a criminal history or who had been deported before, or who had worked for the Cuban government. But it has not been clear to me whether they would actually be repatriated or simply just not allowed to adjust, because we do not – you know, we cannot remove people or deport people to Cuba. And it’s not clear –

MR. CADMAN: Let me add, if I may –

MS. VAUGHAN: – that Mexico would actually take them back, either.

MR. CADMAN: Let me add, if I may, also that with regard to criminal histories or work for the Cuban government, the immigration officers at that port of entry don’t really know whether or not these individuals have a criminal history in Cuba or have worked for the Cuban government except to the extent that an individual reveals that, because the relationship with Cuba is not such that the Cuban police authorities share that information or that the Cuban government shares information about its former employees and bureaucrats. So, you know, there is ever possibility that some of the individuals being paroled into the United States do, in fact, have criminal histories in Cuba. And if they don’t admit to it, we don’t have any way to know that.

Q: Thanks. That was my next question. Appreciate it.

MR. GRIFFITH: OK, on to the next question. This one will be from White; last four digits of your phone number are 8963. Please wait for the unmute to begin your question.

Q: Hi, yeah. This is Peter White in Congressman Mo Brooks’ office.

I was wondering if any of the Latin American countries have commented on or spoken out on the CAA.

MS. LUNA: I will speak to that. The Central American countries have indeed spoken out on the Cuban Adjustment Act, and have been very clear on identifying it as a factor that is attracting these flows. Not only that, they have made calls for it to be repealed, and additionally they have identified the current flow of migrants as not being refugees.

For example, the Foreign Ministry of Guatemala has said that these people are not political refugees; they have not been affected by war or natural disaster. They migrate for the same reasons Guatemalans do, identifying economic improvement and family unification as the factors that are causing migration from Guatemala.

In addition, the Costa Rican government has also called for – identified the Cuban Adjustment Act as the main pull factor for these flows. And actually, late last week the ambassador from Costa Rica to the United States spoke to the nature of parole that is identified in the Cuban Adjustment Act. And as Dan pointed out, he highlighted the notion of interpretation of parole and identified that it’s really a question of political will whether we continue to parole Cubans or not, and that it’s not a matter of – it doesn’t require an action of Congress in order to halt these flows. It requires – it could take an executive action and changing interpretation of parole in order to at least end that immediate access to the United States.

MR. CADMAN: And it’s important to note that under the Obama administration there is, in fact, a policy memorandum that has been issued as guidance by Customs and Border Protection headquarters which pretty much requires the inspecting officers at the ports of entry to act as they have been in paroling these individuals by the thousands. And I would note that that seems to be in contradiction with the Immigration and Nationality Act, which specifies that parole is to be granted sparingly and only on a case-by-case basis; whereas, as we can see from what’s happened, it’s being applied to an entire class of individuals with no discrimination as to who, why or where, other than you’re a Cuban, which is contrary to the whole premise of parole.

MS. VAUGHAN: Right. There’s no question that, with – if these Central American countries through which the migrants are passing, Cubans and others, didn’t have some certainty that the United States was going to accept these migrants, their policies would be different as well. And we certainly – and they are different. I mean, they have no interest in accommodating these migrants.

When we met with the senior official from the Mexican Institute for Migration, we asked her specifically: Do any of the Cubans want to stay in Mexico? And she said, oh, no, we know they all want to go to the United States. One tried that I remember, this guy said he wanted to stay in Mexico, but we told him you don’t have any ties here and you don’t have any money, so you can’t stay in Mexico, so you’re going to the United States. I mean, they’re well aware that the – you know, the official policy of the U.S. government right now is to take one, take all.

MR. GRIFFITH: OK, we’ll move on to the next question. Just as a reminder, if anybody wants to enter the question-and-answer queue, you just press star-six and then the number one.

Next question is from last four digits 8185.

Q: Hi. Actually, you know, I did read, you know, that Nicaragua and Costa Rica have closed down their borders for a little while now, but that Panama now is doing the same. How do you expect that to impact the numbers making it to the southern border here?

MR. CADMAN: This is – this is Dan. I’ll take that one. It is interesting that Nicaragua shut its borders, which left Costa Rica in kind of a bind for a while because the flow had been enter Costa Rica as a tourist, migrate through the Costa Rica-Nicaragua border en route upward toward the United States. And the Nicaraguans decided that they had had enough and that they weren’t going to accept that anymore, and shut down the border, which is one of the reasons that Costa Rica is now changing its approach.

But my – excuse me, my own view is, as with Kausha having mentioned before that Ecuador is now a route, is that unless and until there is a firm policy on the part of the United States to discourage and impede this flow, if one country shuts down, as long as there are a multiplicity of other countries willing to put up with it as long as we act in our country as the escape valve, the individuals are just simply going to shift their route, with the assistance of the smugglers and the organizations that are active right now to get them up the port of entry at Laredo or wherever. They’ll just shift how they get here. But as long as the impetus is here to allow them to enter, then it will continue.

MS. LUNA: And let me add to that that when we spoke to officials, both CBP and the Mexican officials, they noted that and speculated that, as these Central American countries continue to close their borders, the shift could happen to Cubans leaving Cuba via maritime, but instead of heading north towards Florida they will head towards the Yucatan Peninsula instead.

MR. GRIFFITH: There are currently no other questions in the queue, Jessica.

MS. VAUGHAN: All right. Well, thank you all very much. I hope you will check out our reports on our website – again, https://cis.org/. And please feel free to contact any one of us, either directly or through our website, or through our media director, Marguerite Telford. Her email address is [email protected]. Thank you, and have a great day.

(END)