Thank you for the opportunity to testify on the effects of the Obama administration's termination of the enforcement policies and practices established under the Secure Communities program (SC) and their replacement with the Priority Enforcement Program (PEP). Since the implementation of PEP, there has been a significant decline in interior enforcement activity by ICE, with noticeably fewer criminal aliens being arrested by ICE and processed for deportation. This is occurring for three reasons: 1) because the new, more restrictive PEP prioritization scheme exempts a larger number of criminal aliens from deportation; 2) because PEP imposes new logistical hurdles for ICE, most notably the requirement that an alien be convicted before ICE takes custody — which can enable a criminal alien to abscond from facing charges, or in some cases walk out of a courthouse or jail before ICE is aware that the offender is being released; and 3) because PEP explicitly allows local governments to impose non-cooperation or sanctuary policies on local law enforcement agencies. The unfortunate result of these policies is that fewer criminal aliens are being removed from the country and criminal aliens who formerly would have been removed are now being released back to our communities only to commit new crimes.

Size of the Criminal Alien Population

ICE has estimated that approximately 2.1 million criminal aliens are living in the United States. Of these, about 1.9 million are removable, and the remaining 200,000 are green card holders who committed lesser crimes allowing them to avoid removal. According to ICE, each year about 900,000 aliens are criminally arrested. And, each year about 700,000 aliens are released from correctional custody (jail, prison, or probation). ICE estimates that there are more than 1.2 million criminal aliens who are at large in our communities.1

Needless to say, this large population of criminal aliens imposes enormous costs in American communities — for crime victims, for prosecution and justice, and for the degradation of quality of life that results. ICE officials have separately estimated that approximately 50 percent of these aliens will reoffend if released.

Background on Secure Communities

The mandate for Secure Communities dates back more than 15 years, to several cases of missed opportunities in apprehending criminal aliens who committed horrific crimes and drew the attention of lawmakers.2These include Rafael Resendez-Ramirez, the infamous "Railway Killer", who was linked to more than a dozen murders, many of which occurred in Texas. SC is part of a larger federal upgrade of information and identification systems that was coordinated by the FBI, known as Next Generation Identification. With respect to immigration law enforcement in particular, SC is an upgrade to the Institutional Removal and Criminal Alien Programs, and a response to longstanding congressional interest in facilitating the identification and removal of aliens who are a threat to public safety and well-being. It operates in complement with ICE's Law Enforcement Support Center, which is a 24/7 call center that responds to queries from official entities seeking information on the status of non-citizens. These queries can be made by telephone or sent electronically through the National Law Enforcement Telecommunications System (NLETS). The implementation of SC eliminated the need for manual queries by law enforcement officers, and made it comprehensive so that all those arrested were subject to screening based on the fingerprints.

The primary goal of SC was "to identify and process all criminal aliens amenable for removal while in federal, state and local custody."3 (Emphasis added.)

ICE officers do not patrol our streets; like other federal agencies, they depend on referrals from state and local law enforcement agencies to identify aliens who are causing problems in American communities. To replicate the benefits of SC, ICE would have to station thousands of agents in every jail in the United States, 24/7/365, to screen all those arrested. SC benefits local agencies by greatly reducing the time spent questioning inmates and querying ICE. Because it is based on biometrics, it also prevents criminals from evading detection with aliases and false identification. Unlike PEP, it prevents racial and ethnic profiling, because everyone who is arrested is screened, and local law enforcement agencies cannot pick and choose which inmates are subject to immigration screening.

Harris County, Texas, was one of two initial pilot jurisdictions for SC, beginning in November 2008. As of January 2013 SC was operational in all 3,181 jurisdictions in the United States.

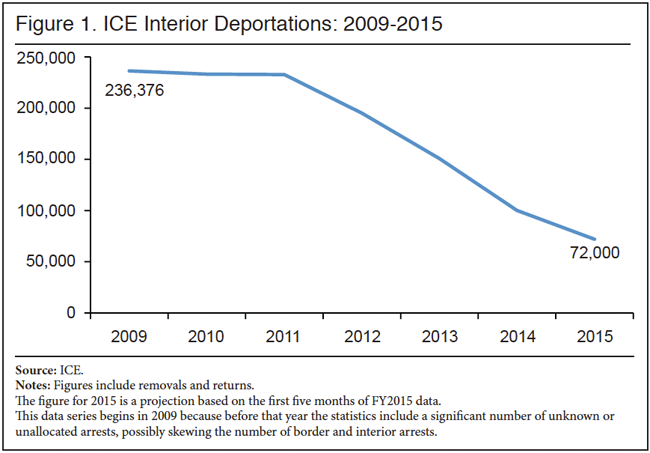

By 2011, when SC had been implemented throughout most of the United States, ICE was able to identify more criminal aliens than ever before. This was the peak of interior and criminal alien removals under the Obama administration.

These figures are deportations of aliens from within the interior of the United States by Immigration and Customs Enforcement (ICE). They do not include deportations effected by the Border Patrol or other DHS agencies, nor do they include deportations by ICE of aliens apprehended while crossing illegally into the United States (also known as "recent border crossers").

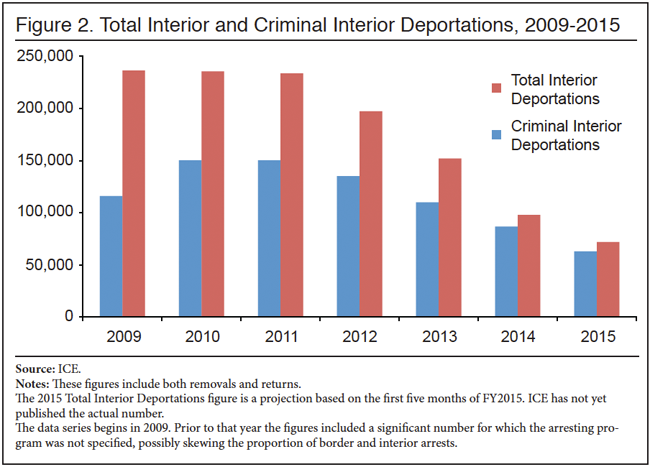

This figure breaks out interior criminal alien deportations (the first bar in each pair) as a subset of total interior deportations (the second, higher, bar in each pair). Criminal aliens are non-citizens who have been convicted of a crime.

Beginning in 2012, the Obama administration began to scale back enforcement by imposing new guidelines on the types of cases ICE officers could pursue, and by restricting instances in which ICE officers were allowed to issue detainers. In general, ICE officers were to refrain from taking enforcement action against illegal aliens unless they had been convicted or charged with a serious crime, convicted of a felony or at least three misdemeanors, or had been deported before. This caused the number of enforcement actions, and eventually the number of deportations, to decline.

The Priority Enforcement Program (PEP)

In November 2014, as part of a set of sweeping executive actions, the Obama administration announced the termination of the Secure Communities program and the implementation of PEP as a substitute. The guidelines for enforcement activity were tightened to require criminal convictions before ICE officers could take action, to exempt those who had been deported before January 1, 2014, to exempt those who were convicted of identity theft, immigration fraud, or similar crimes; to apply federal definitions or classification for crimes instead of state definitions; and to exempt from deportation those aliens with a long list of vaguely-defined "humanitarian" concerns, including U.S.-born or legally resident family members, ties to the community, and health problems, among other conditions. In addition, other DHS enforcement agencies such as the Border Patrol were also told to adjust their practices to comply with these priorities.

The result, as illustrated by the figures above, is that enforcement activity has declined significantly since the implementation of PEP. Not only have total interior deportations fallen sharply, but deportations of criminal aliens have also fallen, despite the administration's insistence that criminal aliens are the highest priority for ICE. ICE claims that it is focused like a laser on deporting "the worst of the worst", but the reality is that these policies are allowing many of "the worst" to remain in American communities.

Post-Conviction Enforcement Fails Public Safety Tests

As mentioned, the PEP rules call for ICE to wait, in most cases, until the alien has been convicted of a crime before ICE will take custody of a removable alien. The Chairman of the U.S. Senate Judiciary, Chuck Grassley, has called this policy a "moral hazard".

A recent case illustrates the problem with this approach. In Omaha, Neb., on January 31, 2016, an illegal alien named Eswin Mejia, age 19, was drag racing while drunk and crashed his pick-up truck into the back of a car driven by Sarah Root, age 21. She died in the hospital soon after, just a day after her graduation from college. Mejia was arrested several days later for felony motor vehicle homicide. He had prior infractions as well. Bail was set at $50,000. Knowing Mejia was an illegal alien, local police contacted ICE and urgently requested a detainer, fearing he would flee after making bail. ICE refused, saying that Mejia "did not meet ICE's enforcement priorities". Mejia has since disappeared, and ICE Director Sarah Saldana has testified that he is now a top priority for apprehension.4

The following table illustrates the decline in enforcement activity in Texas since the implementation of PEP.

ICE Enforcement Metrics for Texas, Oklahoma, and New Mexico: 2014 (under SC) and 2015 (under PEP)

| 2014-Total | 2015-Total | Change | 2014-Criminal | 2015-Criminal | Change | |

| Encounters | 69,369 | 58,844 | -15% | 42,471 | 32,671 | -23% |

| Arrests | 50,760 | 35,376 | -30% | 38,822 | 30,177 | -22% |

| Detainers | 35,837 | 22,164 | -38% | 26,811 | 16,306 | -39% |

| Charging Documents Issued | 34,277 | 21,916 | -36% | 21,809 | 17,060 | -22% |

| Deportations | 177,450 | 143,596 | -19% | 86,451 | 77,831 | -10% |

This table shows the change in ICE enforcement activity from FY2014 (when Secure Communities priorities were in effect) to FY2015 (after the Priority Enforcement Program (PEP) was implemented). The statistics are for ICE Field Offices in Dallas (includes Oklahoma), El Paso (includes New Mexico), Houston, and San Antonio.

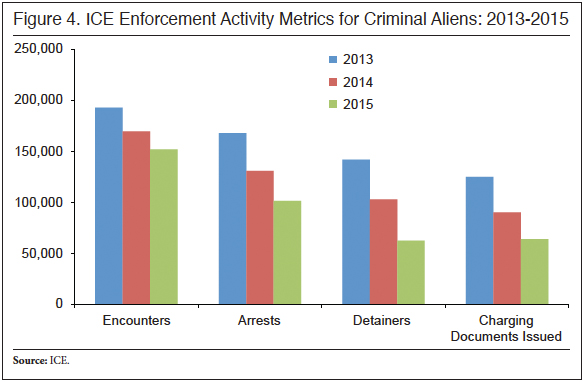

Nationally, under PEP, ICE enforcement activity is at half the level that ICE attained under the Secure Communities protocols. Again, this is not because there are fewer criminals for ICE to arrest (the size of the illegal population living in the United States has not declined), but because ICE officers are not allowed to process as many illegal aliens and criminal aliens as they were before November 2014.

This figure shows the total change in ICE enforcement activity nationwide. Under PEP priorities, the number of detainers and charging documents issued by ICE is approximately one-half of the number issued by ICE in 2013 under Secure Communities priorities.

PEP Creates Logistical Hurdles for ICE

PEP makes it harder for ICE to take custody of criminal alien offenders who are identified through fingerprint matching or after referral from a local law enforcement agency because it restricts use of detainers. This is one of the main differences from Secure Communities. Under Secure Communities, ICE could take action to prevent an alien's release from the time of initial booking into local custody, and the alien could not be released before ICE could take custody. Now, ICE has to wait until the outcome of charges, which cannot be predicted, and the practical result is that some aliens will be able to walk out of custody before ICE can act. For example, an alien who has been in jail for several months awaiting trial has his hearing, is found guilty, and is sentenced to time served. That offender could be released immediately from the courthouse, and even if the local authorities notify ICE, realistically ICE most likely cannot dispatch officers quickly enough to arrest the convicted criminal alien. It's impossible for ICE to station officers in every courthouse waiting to see if illegal aliens are convicted of whatever crimes they commit. This program opens up huge cracks in the system of deporting criminal aliens. One Texas sheriff told me that potentially as many of 40 percent of the criminal aliens in his jail would fall into this category, and likely would escape immigration enforcement as a result of PEP.

PEP Facilitates Sanctuary Policies

In addition to scaling back enforcement activity by ICE, the PEP policy explicitly allows state and local governments to enact sanctuary policies that obstruct immigration enforcement and restrict local law enforcement agencies from cooperating with ICE and the Border Patrol. In the November 20 memorandum establishing PEP, DHS Secretary Johnson stated: "Nothing in this memorandum shall prevent ICE from seeking the transfer of an alien from a state or local law enforcement agency when ICE has otherwise determined that the alien is a priority. ... and the state or locality agrees to cooperate with such transfer." (Emphasis added.)

The effect of this language is that local governments could adopt policies or ordinances that prohibit local law enforcement agencies or officers under their control from cooperating with ICE. This is despite the fact that such non-cooperation policies would be a violation of 8 USC 1373, which says that no government may in any way restrict communication or the exchange of information with federal immigration authorities. In addition, such policies could put a jurisdiction in violation of 8 USC 1324, which prohibits shielding a removable alien from detection by federal authorities.

Such policies are welcomed by criminal aliens and their families, but the consequences can be tragic for other families who suffer harm when these protected criminal aliens re-offend. And we know that they do re-offend. In 2014, one-fourth of the criminal aliens released by sanctuary jurisdictions were arrested again within just eight months.5 According to Texas Department of Public Safety statistics, about 40 percent of criminal aliens arrested in the state are recidivists, either after being released by the feds, the local governments, or because they come back illegally after deportation.

Cooperation with Federal Authorities Does Not Compromise Community Policing

One of the most common claims made by proponents of sanctuary policies is that they are needed to enable immigrants to feel comfortable reporting crimes. This claim has never been substantiated and, in fact, has been refuted by a number of reputable studies. No evidence of a "chilling effect" from local police cooperation with ICE exists in federal or local government data or independent academic research.

Hesitancy to report crime is a problem in many places and is not confined to any one segment of the population. In fact, most crimes are not reported, regardless of the victim's immigration status or ethnicity. Data from the Bureau of Justice Statistics show no meaningful differences among ethnic groups in crime reporting. Overall, Hispanics are slightly more likely to report crimes. Hispanic females especially are slightly more likely than white females and more likely than Hispanic and non-Hispanic males to report violent crimes. This is consistent with academic surveys finding Hispanic females to be more trusting of police than other groups.

A number of academic studies refute the notion that local-federal cooperation in immigration enforcement causes immigrants to refrain from reporting crimes. One example is a major study completed in 2009 by researchers from the University of Virginia and the Police Executive Research Forum (PERF). It found no decline in crime reporting by Hispanics after the implementation of a local police program to screen offenders for immigration status and to refer illegals to ICE for removal. This study also found that the county's tough immigration policies likely resulted in a decline in certain violent crimes.6

The most reputable academic survey of immigrants on crime reporting found that by far the most commonly mentioned reason for not reporting a crime was a language barrier (47 percent), followed by cultural differences (22 percent), and a lack of understanding of the U.S. criminal justice system (15 percent) — not fear of being turned over to immigration authorities.

Data from the Boston, Mass., Police Department, one of two initial pilot sites for ICE's Secure Communities program, show that in the years after the implementation of this program, which ethnic and civil liberties advocates alleged would suppress crime reporting, calls for service decreased proportionately with crime rates. The precincts with larger immigrant populations had less of a decline in reporting than precincts with fewer immigrants.

Similarly, several years of data from the Los Angeles Police Department covering the time period of the implementation of Secure Communities and other ICE initiatives that increased arrests of criminal aliens show that the precincts with the highest percentage foreign-born populations do not have lower crime reporting rates than precincts that are majority black, or that have a smaller foreign-born population, or that have an immigrant population that is more white than Hispanic. The crime reporting rate in Los Angeles is most affected by the amount of crime, not by race, ethnicity, or size of the foreign-born population.

Policy Options for Texas

A number of options are available to state lawmakers to minimize the adverse effects of the implementation of PEP on public safety in Texas. First, it is important that there be consistency state-wide on how non-citizens are handled within the criminal justice system. Lawmakers should not allow jurisdictions where immigration enforcement has become inappropriately politicized or where special interest groups have succeeded in pressuring local officials to adopt sanctuary policies to become the tail that wags the entire state. The standard should be a best practice determined by state officials in consideration of public safety, not a lowest common denominator set by anti-enforcement activist groups.

- No jurisdiction should be permitted to have a sanctuary or non-cooperation policy that is in violation of federal laws. The relevant sections of federal law are 8 USC 1373, which prohibits governments from restricting communication with federal authorities, and 8 USC 1324, which prohibits any person from shielding deportable aliens from detection.

- State and local law enforcement agencies should meet with ICE field office directors to identify areas of concern and to establish protocols and practices to minimize the risk of release of deportable criminal aliens.

- Lawmakers should review state policies on the fingerprinting of offenders to ensure that DHS will be able to receive information on all non-citizens who are arrested.

- Lawmakers should direct state public safety officials to issue guidance and provide training on further steps local law enforcement agencies can take to ascertain the immigration status of offenders, such as NLETS queries to ICE's Law Enforcement Support Center.

- The state should incentivize participation in ICE's 287(g) program, which includes advanced training, delegation of authority, qualified immunity, and direct access to DHS information systems.

Jessica M. Vaughan

Director of Policy Studies

Center for Immigration Studies

Washington, DC

End Notes

1 Jessica Vaughan, "Secure Communities, Please", Center for Immigration Studies, March 14, 2011.

2 IDENT/IAFIS: The Batres Case and the Status of the Integration Project, Dept. of Justice Office of the Inspector General, March 2004, and others.

3 U.S. Immigration and Customs Enforcement, "1st Quarterly Status Report (April-June 2008) for Secure Communities: A Comprehensive Plan to Identify and Remove Criminal Aliens", August 2008.

4 Joseph Morton, "Chuck Grassley invokes Omaha woman's death in criticizing Obama's immigration policy", Omaha World Herald, March 15, 2016.

5 U.S. Immigration and Customs Enforcement, "Declined Detainer Outcome Report", ICE Law Enforcement Systems & Analysis Unit, October 4, 2014. See also Jessica M. Vaughan, "Rejecting Detainers, Endangering Communities: Sanctuaries release thousands of criminals", Center for Immigration Studies, July 2015.

6 For complete references to all the studies cited, see this Center for Immigration Studies < ahref="/Immigration-Policy-Fact-Sheets/immigration-enforcement-and-community-policing" target="_blank">Fact Sheet.