The issue of the impact of immigration on black Americans has long been debated. During the previous great wave of immigration at the turn of the last century, most black leaders such as W.E.B. Dubois, Booker T. Washington and A. Phillip Randolph felt that immigration harmed their community. Job competition has traditionally been the key issue, but other concerns exist as well. For example, the strain illegal immigration may create on public services may be particularly problematic for African Americans because, in many cases, schools and hospitals in some black areas are already stressed. Illegal immigration may add to this problem. There is also concern that by increasing demand, illegal immigration may drive up costs for low-income rental housing. When it comes to possible job competition, there are a number of areas of debate, but there are several areas on which there is general agreement. These areas of agreement are important because they should help frame the debate.

I will start my discussion with three areas on which there is general agreement. I will then move on to areas on which there is less agreement.

Three Areas of Agreement

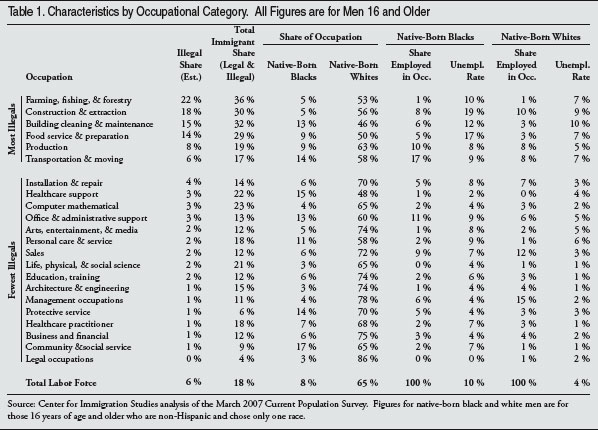

First, there is little debate that illegal immigration primarily, though not exclusively, increases the supply of workers at the bottom end of the labor market. Occupational categories such as building cleaning and maintenance, food service and preparation, and construction are the most heavily impacted (See Table 1). If illegal immigration has a negative impact on U.S.-born workers, it will tend to be on those who have the least education because this is the kind of worker who generally does this type of job.

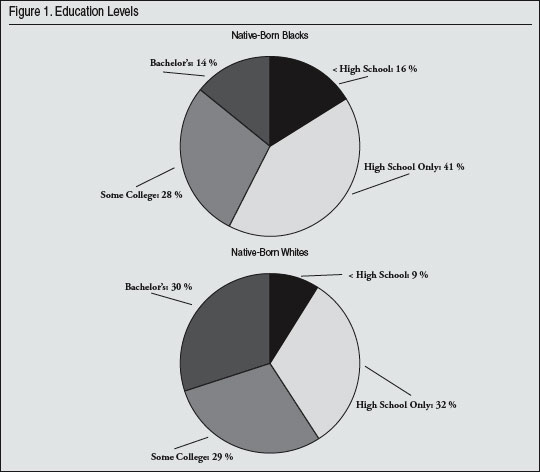

Second, all of the available data show that black men are disproportionately employed at the bottom end of the labor market. Compared to white men, a much larger share of native-born black men have relatively little education. About six out of 10 adult black men have only a high school degree or failed to graduate high school, compared to about four out of 10 white men (see Figure 1). I have estimated, as shown in Table 1, that about half (47 percent) of black men are employed in occupational categories that could be described as illegal-immigrant heavy. And unemployment among black men averages 13 percent in these same occupations. In contrast, only 34 percent of native-born white men are employed in occupations that have a heavy concentration of illegal immigrants; unemployment for white men averages 7 percent.

Third, there is a large body of research showing that less-educated black men, like less-educated workers overall, have generally not fared well in the U.S. labor market in recent years. This is true whether we look at wages, benefits, or labor force attachment. Workers with less than a high school education or those with only a high school education have seen wages decline or stagnate. The share of these workers offered benefits like health insurance by their employers has also declined. And while employment is cyclical, there has been a long-term trend of declining employment and labor force participation for less-educated native-born men, including less-educated black men.1

The overall deterioration in employment rates, wages, and benefits is a strong indication that less-educated labor is not in short supply. If such workers were in short supply, wages and benefits and employment rates would all be rising, as employers try desperately to attract and retain the relatively few workers available. But this seems to be exactly the opposite of what has been happening. The deterioration in the labor market for less-educated black men is particularly problematic because they already tended to make the lowest wages and have the lowest labor force participation rates.

There may be many possible explanations for the problems experienced by less-educated workers. But anyone asserting that labor is in short supply must directly address the declining wages and benefits. For example, if one argues that trade is a key reason for the decline, then it still means that access to foreign labor, through trade, is increasing the effective supply of labor in the United States and exerting downward pressure on wages. If one argues that technological innovation is increasing productivity, which may also increase the effective supply of workers as well as reduce demand for less-skilled workers, then once again the supply of workers is being increased, and this undermines the idea that workers are scarce. Any assertion that less-skilled workers are very scarce must address the overwhelming economic evidence in wages, benefits, and employment to the contrary. Testimonials from employers who understandability wish to keep wages low, is not systematic evidence.

The Impact of Immigration on Black Workers

Several studies have found that immigration has impacted the wages or employment of native-born African Americans. This includes recent studies by Borjas, Grogger, and Hanson that found that immigration reduces labor force participation of the least-educated black men.2 Research by Andrew Sum, Paul Harrington, and Ishwar Khatiwada at Northeastern University has found that immigrants are displacing young native-born men in the labor market and that the largest impact is on blacks and Hispanics.3 In my own research I have found that blacks are more likely to be in competition with immigrants than are whites.4 A 1995 study by Augustine Kposowa concluded that, "non-whites appear to lose jobs to immigrants and their earnings are depressed by immigrants."5 A 1998 study of the New York area by Howell and Mueller found that a 10-percentage-point increase in the immigrant share of an occupation reduced wages of black men about five percentage points. Given the large immigrant share of the occupations they studied, this implies a significant impact on native-born blacks.6

There certainly is a good deal of anecdotal evidence that employers often prefer immigrants, particularly Hispanic and Asian immigrants, over native-born black Americans. A more qualitative study by anthropologist Katherine Newman and Chauncy Lennon of fast food jobs in Harlem, found that immigrants are much more likely to get hired than are native-born black Americans.7

Some studies have not found an impact on blacks from immigration. Most studies that have found little or no impact are based on comparisons of labor market outcomes across cities with different levels of immigrants. Part of the reason it is hard to estimate the effect of immigration in this way is that we live in a national economy. The movement of capital, labor, goods, and services tends to create wage and employment equilibrium between American cities. Moreover, immigrants are attracted to cities with higher wage and employment growth. This will tend to mask the impact of immigration. As a result, comparisons across cities will tend to understate the immigration effect. Studies that have tended to treat the country as one large labor market have found larger effects than have cross city comparisons.

Conclusion

There is no debate that illegal immigration, and even immigration more generally, increases the supply of workers who are employed in lower-skilled, lower-wage sectors of the economy. It is also uncontested that a significant share of native-born black men have education levels that make them more likely to compete with illegal immigrants. Additionally, there is agreement that wages and employment for less-educated men, including black men, have generally stagnated or declined. The lack of wage growth makes it very difficult to argue that less-educated workers are in short supply. There are a number of studies indicating that immigration is harming the labor market prospects of black Americans. However, the debate over whether immigration reduces wages or employment among black Americans is not entirely settled. If one is concerned about less-educated workers in this country, it is difficult to justify continuing high levels of legal and illegal immigration that disproportionately impact the bottom end of the labor market.

It is important to understand that immigration does not simply reduce wages or employment. There is a good deal of agreement among economists that the benefit to more-educated natives that comes from reducing the wages of the least-educated Americans must be very small. A 1997 study by the National Research Council, The New Americans, has a good explanation as to why the gains are so small. There is no body of research showing large economic gains to native-born Americans from immigration. The primary beneficiary of immigration seems to be the immigrants themselves. A central part of the immigration debate is how we weight the benefits that go to immigrants against the losses suffered by the poorest and least-educated Americans. How one answers this question will have a significant impact on what immigration policy makes the most sense.

End Notes

1 See for example, The State of Working America, 2006/07 by Lawrence Mishel, Jared Bernstein, and Sylvia Allegretto.

2Immigration and African-American Employment Opportunities: The Response of Wages, Employment, and Incarceration to Labor Supply Shocks. By George J. Borjas, Jeffrey Grogger, and Gordon H. Hanson

Working Paper 12518.

3The Impact of New Immigrants on Young Native-Born Workers, 2000-2005, September 2006 By Andrew Sum, Paul Harrington, and Ishwar Khatiwada.

4In addition to the results shown in Table 1, which focus on illegal immigration, in a 1998 study published by the Center for Immigration Studies, I found that native-born blacks are more likely to be in competition with immigrants than are whites. The Wages of Immigration: The Effect on the Low-Skilled Labor Market.

5Augustine J. Kposowa, "The Impact of Immigration on Unemployment and Earnings among Racial Minorities in the United States," in Ethnic and Racial Studies, Volume 18, Number 3, July 1995.

6"The Effects of Immigrants on African-American Earnings: A Jobs-Level Analysis of the New York City Labor Market, 1979-89" (November 1997). Levy Economics Institute Working Paper No. 210. By David Howell and Elizabeth Mueller.

7"Finding Work in the Inner City: How Hard Is it Now? How Hard Will it Be for AFDC Recipients?" by Katherine Newman and Chauncy Lennon.