Between 2012 and 2014, the Program for the International Assessment of Adult Competencies (PIAAC) administered a test of English literacy to over 8,000 American adults. The results have been revealing. Using scores from the PIAAC test, my CIS Backgrounder from last month showed that the magnitude and persistence of low English literacy among immigrants is a serious concern, and that immigrants' subjective assessments of their English ability tend to understate the problem.

In a follow-up post, I noted that natives with low earning power also struggle with English literacy. Almost all natives speak English, of course, but many of the least skilled are "functionally illiterate", meaning they have trouble applying their English knowledge to language-intensive tasks. Some economists believe that low-skilled natives can avoid competition with immigrants by specializing in jobs requiring English proficiency, but the PIAAC data suggest that is too optimistic.

This third entry in my PIAAC series puts the focus back on immigrants and attempts to answer a frequently asked question: How well do naturalized citizens score on the English test? Applicants for U.S. citizenship must "be able to read, write, and speak basic English", yet the PIAAC scores are so low among immigrants that it seems unlikely the literacy problem could be limited to the non-naturalized.

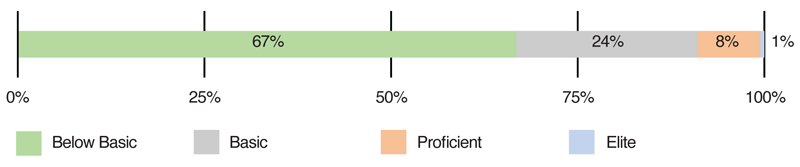

Unfortunately, the PIAAC dataset provides no specific information on citizenship, but there are a couple of ways to address the issue indirectly. The first is to analyze Hispanic immigrants who arrived more than 15 years ago. This group performed especially poorly on the literacy test, with 67 percent scoring "below basic" — a level that some scholars classify as functional illiteracy.

Figure 1. Distribution of Literacy Test Performance by Hispanic Immigrants Who First Arrived More Than 15 Years Ago

Source: CIS analysis of the Program for the International Assessment of Adult Competencies.

Responses are limited to adults ages 16 to 74.

Note: According to the American Community Survey, 50 percent of Hispanic immigrants who first arrived more than 15 years ago are naturalized citizens.

As noted above, the PIAAC dataset cannot tell us how many of the "below basic" scorers are naturalized citizens. However, we know from the American Community Survey (ACS) that 50 percent of Hispanic immigrants who first arrived more than 15 years ago are naturalized. Even if we assume that all of the elite, proficient, and basic scorers in the chart above are naturalized, we have accounted for only two-thirds of the naturalized citizens. Therefore, a minimum of one-third of naturalized Hispanic immigrants who first arrived more than 15 years ago have below basic literacy.

What about naturalized citizens overall? That requires another indirect method. Both the ACS and the PIAAC ask respondents to self-assess their English ability. We can use those self-assessments to link the ACS naturalization data with the PIAAC literacy test scores. Table 1 shows how naturalized immigrants in the ACS self-assess their English-speaking ability, while Table 2 shows the percentage of immigrants in each self-assessed category who score below basic on the PIAAC test.

Table 1. Distribution of Responses by Naturalized Citizens to Census Question:

|

|||

| Speaks English … | Hispanic | Non-Hispanic | All |

| Very well* | 51% | 68% | 63% |

| Well | 26% | 20% | 22% |

| Not well or not at all | 23% | 11% | 15% |

Source: CIS analysis of the 2012-2014 American Community Surveys

* Or only English at home.

Responses are limited to adults ages 16 to 74.

Table 2. Percentage of Immigrants Who Have "Below Basic" Literacy,

|

|||

| Speaks English … | Hispanic | Non-Hispanic | All |

| Very well | 21% | 15% | 16% |

| Well | 56% | 30% | 43% |

| Not well or not at all | 84% | 57% | 80% |

| All naturalized citizens* | 45% | 23% | 32% |

Source: CIS analysis of the Program for the International Assessment of Adult Competencies

* Estimate based on distribution of English ability in previous table.

Responses are limited to adults ages 16 to 74.

The percentage of naturalized citizens who are below basic is just a weighted average of the two tables. For example, we know from Table 1 that 63 percent of naturalized citizens say they speak English "very well", and we know from Table 2 that 16 percent of the "very well" group actually score below basic. Therefore, (16 percent)(63 percent) = 10 percent of naturalized citizens say they speak English "very well" but are below basic. A similar calculation reveals that 9.5 percent of naturalized citizens say they speak English "well" but are below basic, and another 12 percent of naturalized citizens say they speak English "not well or not at all" and are below basic. Add up those percentages, and we get about 32 percent of naturalized citizens who are below basic, as shown in the last row of Table 2.

Based on population counts from the ACS, 32 percent of naturalized citizens equates to over five million people, including roughly equal numbers of Hispanics and non-Hispanics. (Hispanic naturalized citizens are about twice as likely as non-Hispanic naturalized citizens to be below basic, but non-Hispanics outnumber Hispanics by about two to one among naturalized citizens.)

How did millions of immigrants become citizens without basic English literacy? The simple answer is that the government's English test is far less demanding than the PIAAC test. The PIAAC definition of literacy is "understanding, evaluating, using, and engaging with written text to participate in society, to achieve one's goals, and to develop one's knowledge and potential." Simply reading and writing basic English sentences does not necessarily meet that definition. As mentioned above, even some native English speakers struggle to apply their knowledge to language-intensive tasks.

By contrast, naturalization applicants need only "read aloud one out of three sentences correctly" and "write one out of three sentences correctly" to prove their English ability. Does a person who passes this test sound ready to fully participate in the nation's social, economic, and civic interchange? Though its content already seems insufficient, the test is not even required of applicants who have reached certain age and residency milestones. If we are serious about new citizens developing functional English skills, the United States should adopt more rigorous language requirements.