Download a PDF of this Backgrounder

Steven A. Camarota is the Director of Research and Karen Zeigler is a demographer at the Center for Immigration Studies.

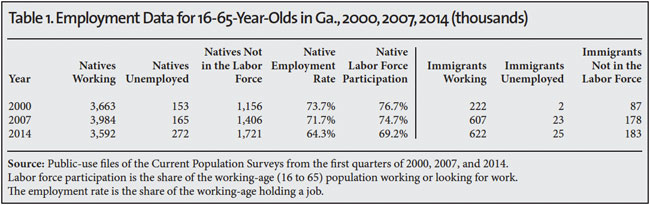

The Gang of Eight immigration bill (S.744) passed by the Senate last June would have roughly doubled the number of new foreign workers allowed into the country, as well as legalized illegal immigrants, partly on the grounds that there is a labor shortage. Many business groups and politicians in Georgia supported the legislation. However, an analysis of government data shows that, since 2000, all of the net increase in the number of working-age (16 to 65) people holding a job in Georgia has gone to immigrants (legal and illegal). This is the case even though the native-born accounted for 54 percent of growth in the state's total working-age population. Perhaps worst of all, the labor force participation rate of Georgia's natives shows no improvement through the first part of this year despite the economic recovery.

Findings:

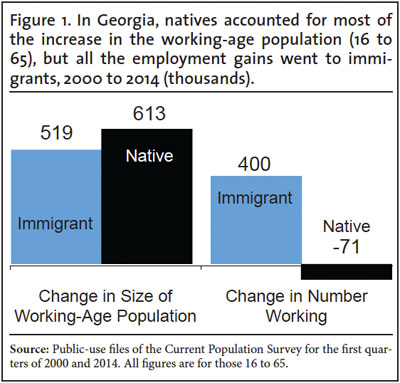

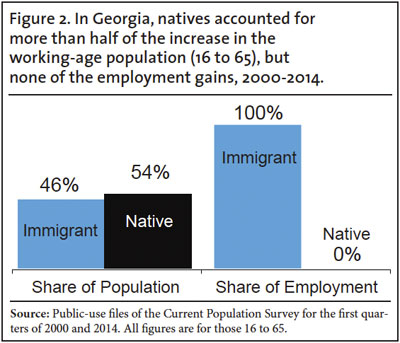

- The total number of working-age (16 to 65) immigrants (legal and illegal) holding a job in Georgia increased by 400,000 from the first quarter of 2000 to the first quarter of 2014, while the number of working-age natives with a job declined by 71,000 over the same time frame.

- The fact that all the long-term net gain in employment among the working-age went to immigrants is striking because natives accounted for 54 percent of the increase in the total size of the state's working-age population.

- In the first quarter of this year, only 64 percent of working-age natives in the state held a job. As recently as 2000, 74 percent of working-age natives in Georgia were working.

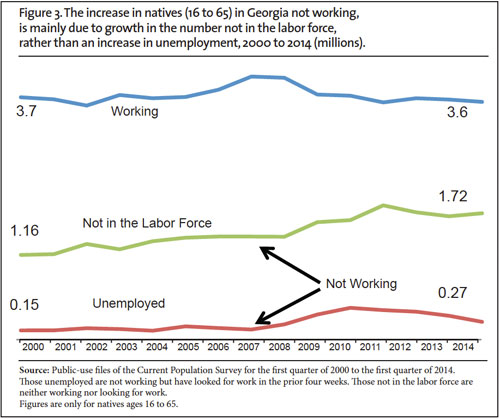

- Because the native working-age population in Georgia grew significantly, but the share working actually fell, there were 684,000 more working-age natives not working in the first quarter of 2014 than in 2000 — a 52 percent increase.

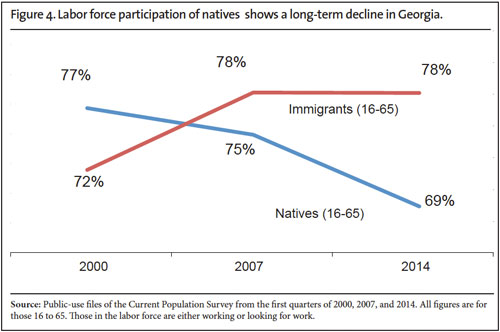

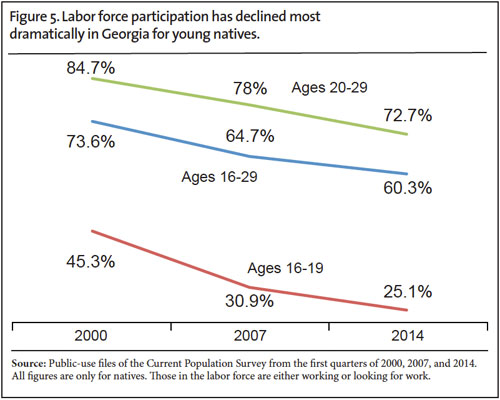

- Perhaps most troubling is that the labor force participation rate (share working or looking for work) of Georgia's working-age natives has not improved, even after the jobs recovery began in 2010.1

- In fact, the labor force participation of natives in Georgia shows a long-term decline, with the rate lower at the last economic peak in 2007 than at the prior peak in 2000.

- The supply of potential workers in Georgia is very large: In the first quarter of 2014, two million working-age natives were not working (unemployed or entirely out of the labor market), as were 208,000 working-age immigrants.

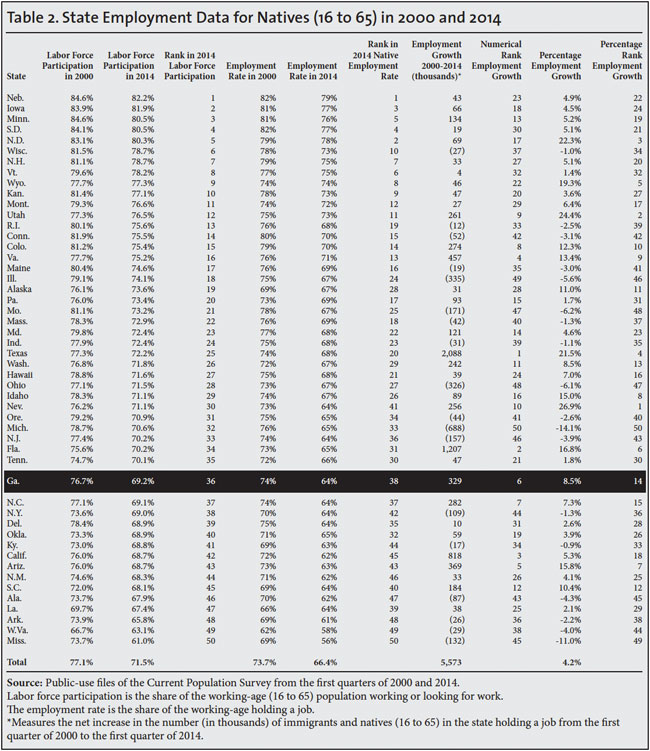

- In terms of the labor-force participation rate among working-age natives, the state ranks 36th in the nation.

- Two key conclusion from the state's employment situation:

- First, the long-term decline in employment for natives in Georgia and the enormous number of working-age natives not working clearly indicates that there is no general labor shortage in the state. Thus, it is very difficult to justify the large increases in foreign workers (skilled and unskilled) that would be allowed into the country by a bill like S.744.

- Second, Georgia's working-age immigrant population grew 167 percent from 2000 to 2014, one of the highest of any state in the nation. Yet the number of working-age natives working in 2014 was actually lower than in 2000. This undermines the argument that immigration, on balance, increases job opportunities for natives.

Data Source

This analysis is based on the "household survey", collected by the government. The survey is officially known as the Current Population Survey (CPS), and is the nation's primary source of labor market information.2 Many jobs are created and lost each quarter and many workers change jobs as well. But the number of people employed reflects the net effect of these changes. We focus on the first quarter of each year 2000 to 2014 in this analysis because comparing the same quarter over time controls for seasonality. We also emphasize the economic peaks in 2000 and 2007 as important points of comparison.

This analysis focuses on those 16 to 65 so that we can examine the labor-force participation rate (share working or looking for work) and the employment rate (share working) of native-born Americans.3 Labor-force participation and the employment rate are measures of labor force attachment that are less sensitive to the business cycle than the often-cited unemployment rate. Immigrants (legal and illegal) are individuals who are not U.S. citizens at birth. Prior research indicates that about half of immigrants in Georgia are in the country illegally.4

Click on the table for a larger version

Click on the table for a larger version

End Notes

1 In the first quarter of 2010, 71.8 percent of natives 16 to 65 in Georgia were in the labor force; in 2011 it was 68.7 percent; in 2012 it was 70.1 percent; and in 2013 it was 70.3 percent. In the first quarter of 2014 it was 69.2 percent. These small changes represent sampling variability and therefore there has been no statistically significant change in the labor force participation of working-age natives in Georgia since 2011.

2 The Current Population Survey does not include those in institutions such as prisons. We do not use the "establishment survey", which measures employment by asking businesses, because that survey is not available to the public for analysis. Equally important, it does not ask if an employee is an immigrant.

3 Those 16 to 65 years of age account for some 95 percent of all workers. When examining the share working or in the labor force it is necessary to limit the age range because, although the under-16 and over-65 populations are quite large, only a small share work.

4 Based on the American Community Survey (ACS), the Department of Homeland Security estimated 400,000 illegal immigrants in the state in 2012 (see Appendix). The ACS found that the total immigrant population (legal and illegal, working and not working, of all ages) in the state in 2012 was 941,000. The Department of Homeland Security and others have estimated that about 90 percent of illegal immigrants are included in Census Bureau data such as the CPS and ACS. Thus, in 2012 about 45 percent of Georgia's immigrant population were illegal aliens. The monthly CPS (2012 to 2014) shows modest growth in the state's total foreign-born so it is unlikely that the illegal share of the state's immigrant population changed significantly between 2012 and 2014.