Download a PDF of this Backgrounder.

Jason Richwine, PhD, is a public policy analyst based in Washington, D.C., and a contributing writer at National Review.

One of the many trade-offs inherent to immigration policy is efficiency vs. distribution in the labor market. Importing more workers from abroad can lower the cost of production, but the savings come in large part from holding down wages. Anyone who claims that immigration offers only benefits or only costs to the labor market is not being honest about the issue. Unfortunately, immigration advocates have a habit of developing exactly those sorts of one-sided talking points. One of the most prominent right now is the idea of a "labor shortage". Forget all this talk about trade-offs, they say, employers simply cannot find any more workers without immigration.

That claim is false. Neither theory nor evidence backs the existence of a "labor shortage". As discussed below, when employers complain of a "shortage", they really mean a shortage of people willing to work for the (low) wage that employers would like to pay. The percentage of working-age Americans in the labor force remains significantly below the level from the year 2000, and employers should strive to bring those potential workers back.

Key Points

- Shortages should not occur in a free market.

- Tight labor markets benefit marginalized groups.

- Wages have been stagnant over the long term.

- Labor force participation is down over the long term.

- Domestic industries should hire Americans.

- Natives participate in all major occupations.

- Plenty of STEM workers are available.

- Gains to the economy are not the same as gains to natives.

- Immigration is not an efficient solution to population aging.

Shortages Should Not Occur in a Free Market

A shortage implies that we have somehow run out of workers to fill essential jobs. Even just on an intuitive level, this seems unlikely. After all, how could the world's largest economy, boasting a population of 329 million, have no one available to work in large industries such as farming, or construction, or software development? And if the United States is in dire need of more workers, how do countries with far smaller labor forces, such as South Korea or Finland, maintain such strong economies?

The answer, of course, is that none of these countries has run of out of workers. In fact, the very notion of a "shortage" in a free market economy is dubious. As long as prices are free to adjust, the market will generally do a good job of matching supply with demand. If the demand for a particular good or service increases, buyers will be willing to pay a higher price, which causes more suppliers to come into the market. That's why we can always take our car to the gas station and fill up the tank, even though the world oil market is routinely buffeted by supply and demand shocks. The price of gasoline changes to absorb those shocks, thus ensuring enough supply to meet demand. It is only when gas prices are not allowed to rise — for example, the Nixon- and Carter-era price controls — that we get genuine shortages.

The market for labor works in a similar way. Employers demand labor, workers supply it, and the market wage is the price at which they meet. Just as with gasoline, there should not be a shortage of labor as long as the price (the wage) can rise. If employers demand more labor, they need to increase the wage in order to increase the supply of workers, just as the price of gasoline rises when demand increases.

When employers today complain of a "labor shortage", what they really mean is there are not enough Americans willing to work at the wage employers want to pay. Employers' unwillingness to raise wages gives the appearance of a "shortage," for which employers claim the only solution is to increase the labor supply by bringing in workers from abroad.

Tight Labor Markets Benefit Marginalized Groups

Sometimes employers are explicit about their desire to keep wages low through immigration. For example, a 2015 report from the farm lobby argued that 0.6 percent annual wage increases for field workers are "a strain on many U.S. farms", and that more guestworkers are needed "to fill job vacancies without upward pressure on wages."1

The better outcome for American workers would be to raise wages. In fact, a tight labor market is the rare uplift program that does not require any new taxes or regulations. It naturally incentivizes employers to raise wages, improve working conditions, and recruit from marginalized groups.

"The tightest labor market in more than half a century is finally lifting the wages of the least-skilled workers on the bottom rung of the labor force, bucking years of stagnation," according to the New York Times.2

"[B]ig companies such as Walmart and Koch Industries ... are turning to an underutilized source of labor: inmates and the formerly incarcerated," according to the Washington Post.3

The low unemployment rate "has brought record numbers of people with disabilities into the workforce," also according to the Post.4

It would be a shame to short-circuit employer outreach to marginalized Americans by importing more foreign workers instead.

Wages Have Been Stagnant Over the Long Term

Despite the recent outreach, the long-term wage trend in the United States is discouraging. According to Pew, "Today's average hourly wage has just about the same purchasing power it did in 1978, following a long slide in the 1980s and early 1990s and bumpy, inconsistent growth since then. In fact, in real terms average hourly earnings peaked more than 45 years ago."5 Since 2000, the bottom quarter of earners saw just a 4.3 percent real-wage increase — equivalent to an annual raise of just 0.2 percent.

Labor Force Participation Is Down Over the Long Term

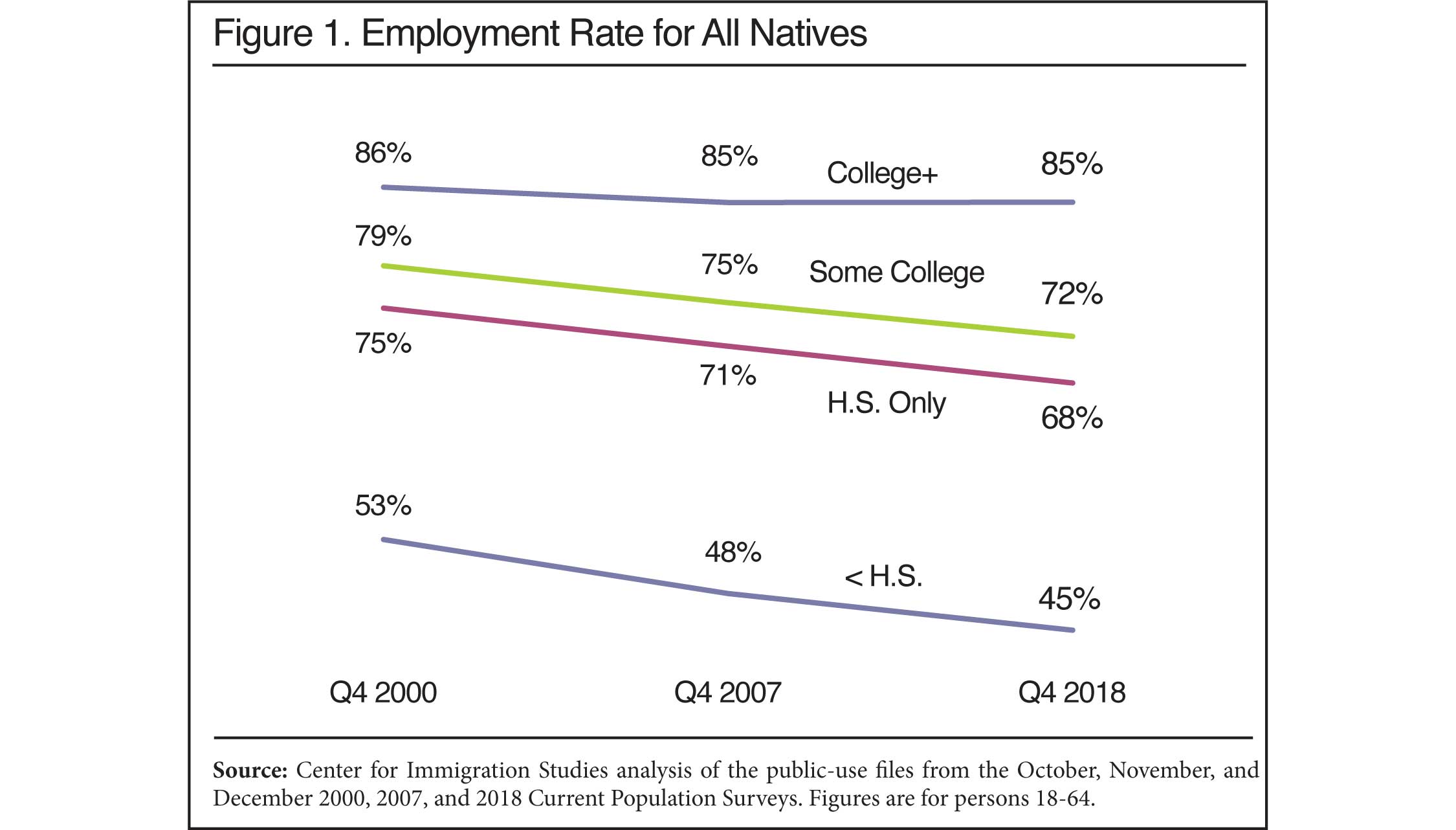

The current unemployment rate of 3.8 percent is historically low, but that figure includes only people who are working or who have looked for work in the past month. The long-term trend in overall employment — including people who say they haven't been looking for work — has been downward.6 Among working-age natives who do not have a bachelor's degree and are not incarcerated, the percentage who were employed fell from 73 percent in 2000 to 67 percent in 2018. In absolute terms, nearly 35 million less-skilled, working-age Americans do not have jobs in the midst of this "labor shortage".

|

Granted, some people who have dropped out of the labor force have significant personal problems, such as criminal records, drug abuse, and welfare dependency. Re-integrating these downtrodden Americans will be a challenge. However, importing more workers from abroad allows us to ignore that challenge rather than confront it head on.7

Domestic Industries Should Hire Americans

Some employers of low-skill labor, particularly farmers, insist that raising wages is out of the question. They say higher wages would damage their industry because it would raise the price of domestic goods, and consumers would opt for cheaper foreign goods instead. This is effectively an argument for open borders. Almost any goods-producing industry in the United States could argue that it loses at least some level of sales to foreign companies because the U.S. labor pool has not been sufficiently augmented with immigrants.

If an American manufacturer cannot survive by hiring Americans, then perhaps it should not survive in its present form. After all, in a free trade context we often hear that if foreign countries can produce certain goods more cheaply than we can, then American industry should refocus on different products on which it has a comparative advantage. The main argument for preserving a domestic industry is that it keeps jobs in the United States, but employers want to preserve the industry without the jobs for Americans. Surely the benefit to Americans of maintaining a particular domestic industry is much attenuated if that industry does not employ Americans.

Natives Participate in All Major Occupations

Some employers argue that, even if they could raise wages, natives will never do certain jobs because the working conditions are so bad. One might respond that limiting immigration would incentivize employers to pursue automation and improve conditions for the remaining workers. More to the point, however, natives are well represented in all major occupations.8 While the data obviously cannot speak to every individual job in the economy, the Census Bureau has sorted workers into 474 different occupational groups. Natives are a majority of the workers in all but six of those occupations. Even within those six majority-immigrant occupations, natives are still 46 percent of all workers.

Of course, there are more majority-immigrant occupations in localities with high levels of immigration, but natives clearly are willing to do these jobs. In low-immigration cities such as Pittsburgh, the houses still get built, the lawns still get mowed, and the hotel beds still get made. Moreover, Canada and Australia maintain thriving first-world economies without huge flows of low-skill workers from abroad, although they both admit significant numbers of skilled immigrants.

Plenty of STEM Workers Are Available

While farmers and other employers of low-skill labor are sometimes open about their desire to pay low wages, companies looking to bring in high-skill immigrants generally insist that the "labor shortage" they face has nothing to do with wages. Instead, they claim they simply cannot find Americans with the needed skills.

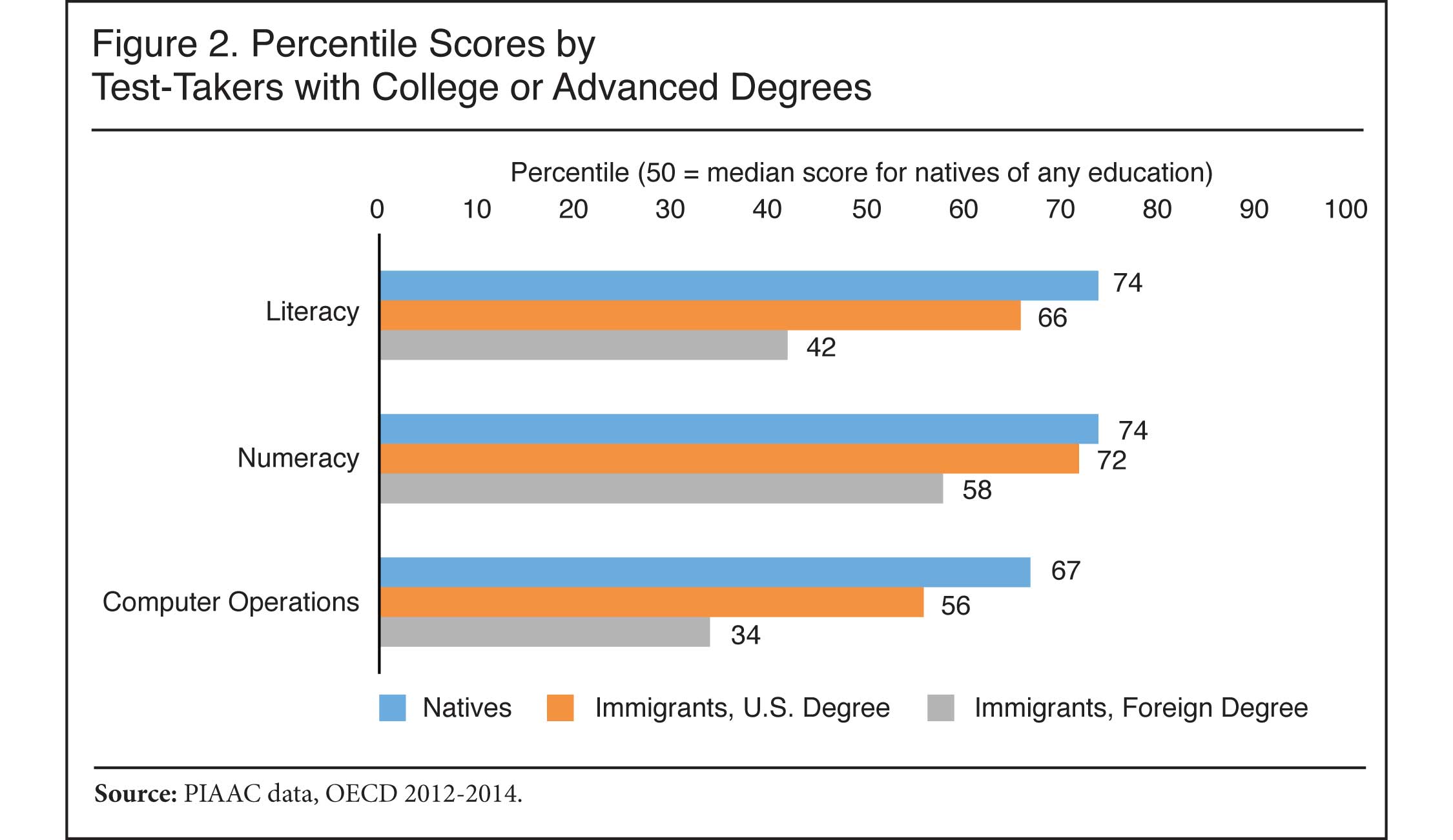

That claim is most commonly heard from the technology industry, but it is inconsistent with several facts. First, only about one third of natives with college degrees in STEM fields actually hold STEM jobs — surely they could be recruited before bringing in foreigners?9 Second, U.S.-educated immigrants with college degrees are no more skilled, on average, than comparably educated natives, and foreign-educated immigrants are substantially less skilled.10

|

Third, companies that lose the lottery for H-1B workers do not have lower levels of employment than companies that win the lottery.11 Presumably, companies who lose out on hiring an immigrant simply go ahead and hire an American for the job.

Some immigrants with "high-skill" visas are Einstein-level talents, but most are just run-of-the-mill college graduates, similar to the 65 million working-age college graduates the United States already has. Adding more could certainly have some positive economic effects, but there is no "shortage" of them in the United States. Again, it is not plausible that a $21 trillion economy with the world's third largest population and a vast system of higher education is unable to produce, say, computer programmers.

Gains to the Economy Are Not the Same As Gains to Natives

Isn't it always "good for the economy" to have more workers? Yes, but it is important to understand the difference between "the economy" as measured by total GDP and individual earnings as measured by per capita GDP:

Imagine that the United States clones itself. From our population of 329 million, we create another 329 million people whose distribution of skills exactly mirror that of the existing population. The clones also come with a stock of capital equipment identical to the country's pre-existing capital. By doubling labor and capital, we double our GDP. "Cloning is essential to our economy," advocates declare. "Without it, we would be only half as rich as we are now." Is that argument persuasive?

Of course not. The clones make the U.S. economy larger, but per-capita income stays the same, leaving the average person no better off than before. Put another way, the clones double the economic pie and then promptly eat half of it themselves.12

It is per capita GDP, not total GDP, that measures living standards. Anyone who doubts that should remember that Bangladesh has a higher total GDP than New Zealand, but New Zealand obviously has a higher standard of living.

Although the distinction between gains to the economy vs. gains to natives seems like a simple one, the media are frequently confused by it. CNN once warned that the Cotton-Perdue RAISE Act — which would reduce immigration over the long term by eliminating chain migration — would lead to "4.6 million lost jobs by the year 2040". As I commented at the time:

What the CNN reporters mean by "jobs", however, is "workers". There will be 4.6 million fewer workers in the United States under the RAISE Act because there will be roughly 10 million fewer immigrants! All this result says is that a smaller population will have a smaller number of workers than a larger population. It says nothing about the economic impact on Americans.

In fact, the report itself hints that Americans will have more job opportunities: "The RAISE Act also reduces employment because the domestic worker participation rate won't increase enough to fill the jobs that would have been held by immigrants who are no longer allowed in the country." That suggests not only that Americans will work more under the RAISE Act, but also that the "lost jobs" will be lost not by Americans, but by the immigrants who would not arrive.13

Again, immigration has a variety of economic effects, both positive and negative, but a larger GDP by itself has little impact on the average American — unless per-capita GDP is rising with it.

Immigration Is Not an Efficient Solution to Population Aging

Due to population aging, the ratio of workers to retirees in industrialized nations is declining, resulting in lower productivity and strains on social services. This is a genuine long-term problem, but it is not the cause of the "labor shortage" alleged to exist today. As explained above, employers claim a labor shortage because they do not wish to raise wages sufficiently to recruit the tens of millions of working-age Americans who are out of the labor force. Population aging really is a separate issue, but since it so often comes up in the context of a "shortage", it's worth a few comments here.

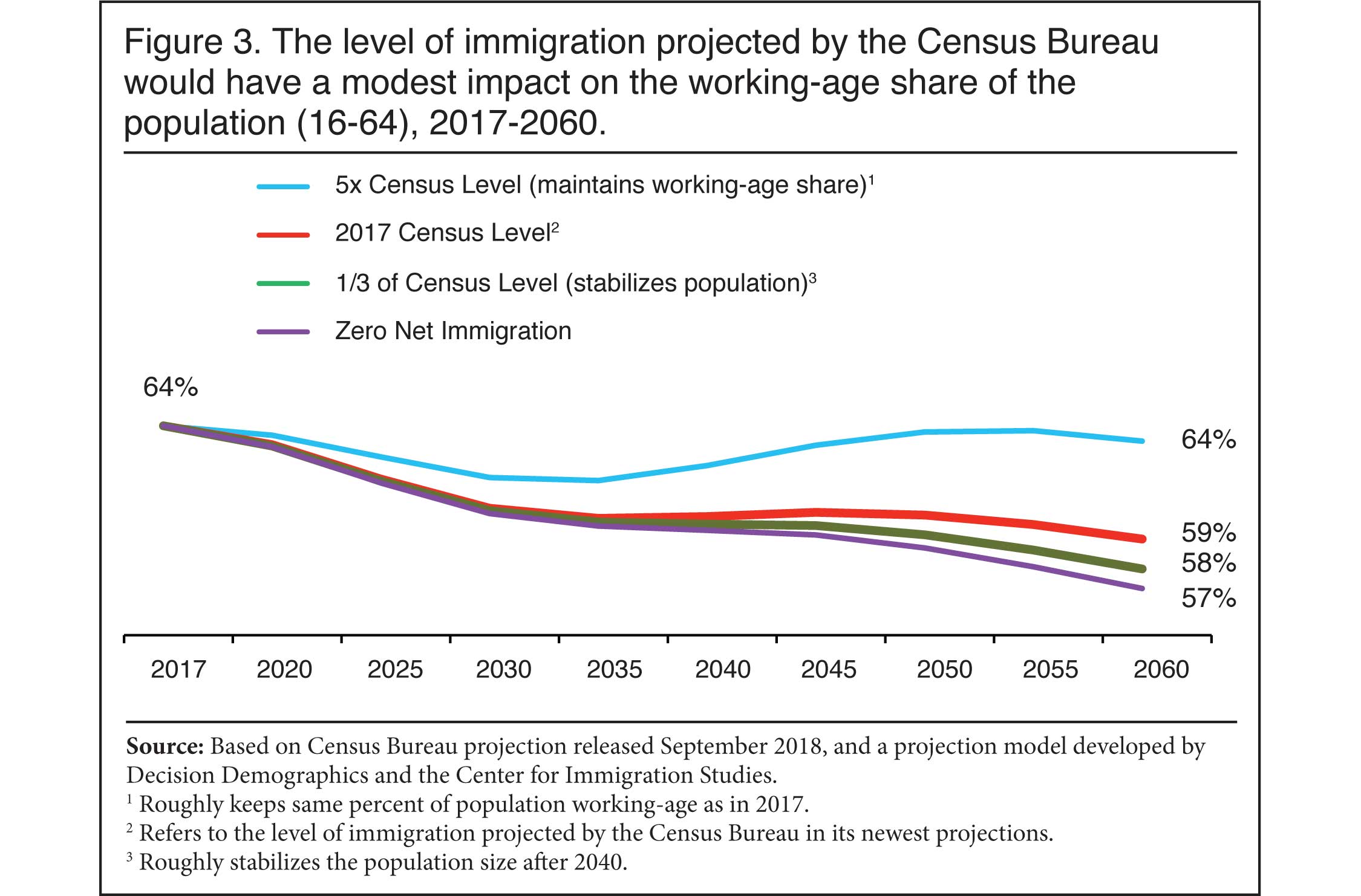

Immigration can certainly improve the worker to retiree ratio, but it is a "highly inefficient" method of doing so, in the words of the Census Bureau.14 In a 1992 article in Demography, economist Carl Schmertmann showed that "constant inflows of immigrants, even at relatively young ages, do not necessarily rejuvenate low-fertility populations."15 In fact, present levels of immigration would need to roughly quintuple over the next 40 years in order to maintain today's share of the population that is working-age.16

|

Among the reasons are that the U.S. population is already large, that immigrants are only modestly younger than natives on average, and that immigrant fertility tends to decline by the second generation. Although the aging problem has no simple solution, coaxing more working-age Americans back into the labor force, along with gradual increases in the retirement age and a boost in fertility (if possible) would be less socially disruptive compared to mass immigration.

Conclusion

Nothing in this report is meant to imply that immigration is entirely costly (or entirely beneficial) to the labor market. As mentioned in the introduction, immigration is fundamentally about trade-offs. Unfortunately, advocates have seized on the idea of a "labor shortage" in order to deny those trade-offs, arguing instead that immigration is necessary to fill jobs that cannot be filled by natives. Neither economic theory nor empirical evidence supports the notion of a "labor shortage". It's time to retire this talking point.

End Notes

1 Jason Richwine, "Farm Lobby: Our Workers Don't Deserve Higher Wages", National Review, August 28, 2015.

2 Eduardo Porter, "Short of Workers, U.S. Builders and Farmers Crave More Immigrants", The New York Times, April 3, 2019.

3 Heather Long, "His Best Employee Is an Inmate from a Prison He Didn't Want Built", The Washington Post, January 26, 2018.

4 Danielle Paquette, "She Cleaned for $3.49 an Hour. A Gas Station Just Offered Her $11.25", The Washington Post, June 21, 2018.

5 Drew DeSilver, "For Most U.S. Workers, Real Wages Have Barely Budged in Decades", Pew, August 7, 2018.

6 Steven A. Camarota, "The Employment Situation of Immigrants and Natives in the Fourth Quarter of 2018", Center for Immigration Studies Backgrounder, April 11, 2019.

7 Amy Wax and Jason Richwine, "Low-Skill Immigration: A Case for Restriction", American Affairs, Winter 2017.

8 Steven A. Camarota, Jason Richwine, and Karen Zeigler, "There Are No Jobs Americans Won't Do", Center for Immigration Studies Backgrounder, August 26, 2018.

9 Steven A. Camarota and Karen Zeigler, "Is There a STEM Worker Shortage?", Center for Immigration Studies Backgrounder, May 19, 2014.

10 Jason Richwine, "Foreign-Educated Immigrants Are Less Skilled Than U.S. Degree Holders", Center for Immigration Studies Backgrounder, February 24, 2019.

11 Jason Richwine, "On Foreign Tech Workers, the Evidence Is against Marco Rubio", National Review, March 14, 2016.

12 Jason Richwine, "Most of the Gains from Immigration Go to Immigrants Themselves – Not to Natives", Center for Immigration Studies blog, February 10, 2016.

13 Jason Richwine, "Breaking: Fewer Total People Means Fewer Total Workers", Center for Immigration Studies blog, August 10, 2017.

14 Frederick W. Hollmann, Tammany J. Mulder, and Jeffrey E. Kallan, "Methodology and Assumptions for the Population Projections of the United States: 1999 to 2100", Census Bureau, Population Division Working Paper No. 38, January 13, 2000.

15 Carl P. Schmertmann, "Immigrants' Ages and the Structure of Stationary Populations with Below-Replacement Fertility", Demography, November 1992.

16 Steven A. Camarota and Karen Zeigler, "Projecting the Impact of Immigration on the U.S. Population", Center for Immigration Studies Backgrounder, February 4, 2019.