Key Findings

This report examines the justifications given by sanctuary jurisdictions for their policies, and finds them to be largely unfounded:

- Cooperation with immigration enforcement has not been shown to undermine community trust nor cause immigrants to refrain from reporting crimes; there are better ways to address issues of access to police assistance without obstructing enforcement;

- Simply cooperating with federal immigration agencies does not turn local officers into de facto immigration officers, because federal officers make the decisions on which aliens are targeted for deportation;

- Such cooperation is not very costly for local jurisdictions because the removal of criminal aliens spares future victims and saves future supervision, incarceration, and social services costs to criminal aliens. In addition, cooperative localities can receive partial reimbursement for their incarceration costs.

- Claims by some local law enforcement agencies that they need a warrant in order to hold aliens for ICE are dubious but can be accommodated by the issuance of ICE administrative warrants.

The Trump administration has a number of tools available at its disposal and within the confines of executive authority to address the problem of sanctuaries and the public safety problems they create.

Here’s how to do so:

- Rescind the Obama administration actions and policies that encourage and enable sanctuaries, including clarifying that local agencies are expected to comply with detainers;

- Cut federal funding to sanctuaries;

- Initiate civil litigation to enjoin state or local laws and policies that egregiously obstruct enforcement of federal immigration laws and regulations;

- Selectively initiate prosecution under the alien harboring-and-shielding statute, which is a federal felony; and

- When requested, issue administrative warrants to accompany detainers as a reasonable accommodation to state or local concerns. Negotiating over which aliens will be subject to detainers, as is current policy, is not a reasonable accommodation.

- Direct ICE to begin publishing a weekly report providing the public with information on all criminal aliens released by the sanctuaries.

Introduction and Background

The Center for Immigration Studies has tracked the movement, repeatedly spoken out against it,1 and watched as it has grown under the policies of the Obama White House, whose aims have more closely mirrored those of open borders advocates than those of an administration constitutionally charged with faithfully executing the laws of the United States.2 There are now more than 300 state and local governments with laws, rules, or policies that impede federal efforts to enforce immigration laws.3In the past several years, a “sanctuary” movement has arisen in various states and political subdivisions around the country. This movement intends to, and does in fact, obstruct the efforts of federal officers to enforce immigration laws, substituting instead the views of the state or local jurisdiction over how or whether immigration laws will be enforced within its boundaries.

Donald Trump began his dark horse presidential candidacy by campaigning to restore respect for America’s borders and its immigration laws. Included in his platform was the message that sanctuaries which flouted those laws would not be tolerated. In his immigration policy speech in Phoenix in August, Trump said:

“Block funding for sanctuary cities ... no more funding. We will end the sanctuary cities that have resulted in so many needless deaths. Cities that refuse to cooperate with federal authorities will not receive taxpayer dollars, and we will work with Congress to pass legislation to protect those jurisdictions that do assist federal authorities.”

Mr. Trump’s platform resonated with voters and he is now president-elect.

Reacting to Trump’s election, a number of sanctuary cities have declared that they will not retreat from their existing policies. The statements from Mayors Rahm Emanuel of Chicago and Bill DeBlasio of New York, as well as a number of others, have had a particular “throw down the gauntlet” tone to them.4 Several police chiefs have taken a similar approach,5 and one governor has threatened to sue the federal government if it withholds funds from sanctuaries.6

In addition, the students and faculty at a number of colleges and universities nationwide have demanded that administrators declare their campuses to be sanctuaries.7 A publicly supported university in Oregon has done this,8 as have the private Wesleyan and Columbia Universities. Meanwhile these schools collect millions of dollars in federal research funds and are the happy beneficiaries of additional millions from students using federal Pell grants and federally-subsidized student loans to pay for their tuition.9

But even many of those institutions which do not declare themselves sanctuaries already openly accept illegal alien students, in flagrant disregard of the immigration laws, and offer them in-state tuition rates. Ironically, this includes the University of California system, whose president is Janet Napolitano, former secretary of the Department of Homeland Security (DHS) under the Obama administration. The UC system goes so far as to provide an online Undocumented Student Resources guide, declaring that “Undocumented students of all ethnicities and nationalities can find a safe environment and supportive community at the University of California...UC campuses offer a range of support services —from academic and personal counseling, to financial aid and legal advising...”10

The purpose of this paper is to consider the means available to the Trump administration to confront and dissuade sanctuaries and diminish their ability to impede enforcement of federal immigration laws.

What is a "Sanctuary"?

Different people and groups may have different definitions of a sanctuary, and there is a spectrum of such policies across the nation. For our purposes, a sanctuary is a jurisdiction that has a law, ordinance, policy, practice, or rule that deliberately obstructs immigration enforcement, restricts interaction with federal immigration agencies, or shields illegal aliens from detection. In addition, federal law includes two key provisions that forbid certain practices: one that forbids policies restricting communication and information sharing (8 U.S.C. Section 1373) and one that forbids harboring illegal aliens or shielding them from detection (8 U.S.C. Section 1324).

Information exchanges. 8 U.S.C. 1373 states:

“a Federal, State, or local government entity or official may not prohibit, or in any way restrict, any government entity or official from sending to, or receiving from, [federal immigration authorities] information regarding the citizenship or immigration status, lawful or unlawful, of any individual.”

A recent report from the Department of Justice’s Office of Inspector General (DOJ OIG)11, requested by Rep. John Culberson (R-Texas), who chairs the appropriations committee in charge of the DOJ budget, determined that sanctuary policies which prohibit local officers from communicating or exchanging information with ICE are “inconsistent” with federal law. Sanctuary jurisdictions do this by ignoring immigration detainers, which are filed by Immigration and Customs Enforcement (ICE) agents to signal their intent to take custody of aliens for purposes of removal, once state or local justice system proceedings are concluded. Some jurisdictions go further by prohibiting communication to advise or even acknowledge to ICE agents that the alien has been arrested. They also sometimes prevent ICE agents from access to the alien to conduct interviews.

The OIG report investigated the policies of 10 jurisdictions and found that they did indeed limit cooperation with ICE in an improper way:

“[E]ach of the 10 jurisdictions had laws or policies directly related to how those jurisdictions could respond to ICE detainers, and each limited in some way the authority of the jurisdiction to take action with regard to ICE detainers…We also found that the laws and policies in several of the 10 jurisdictions go beyond regulating responses to ICE detainers and also address, in some way, the sharing of information with federal immigration authorities.”

Harboring Aliens in Violation of Law. 8 U.S.C. 1324 states:

“Any person who…knowing or in reckless disregard of the fact that an alien has come to, entered, or remains in the United States in violation of law, conceals, harbors, or shields from detection, or attempts to conceal, harbor, or shield from detection, such alien in any place, …; encourages or induces an alien to come to, enter, or reside in the United States, knowing or in reckless disregard of the fact that such coming to, entry, or residence is or will be in violation of law; or engages in any conspiracy to commit any of the preceding acts, or aids or abets the commission of any of the preceding acts, shall be….fined under title 18, imprisoned not more than 5 years, or both...”12

Much of the sanctuary movement seems to be centered on shielding from federal action deportable aliens who have been arrested and charged with various crimes. But other jurisdictions have more expansive policies aimed at shielding some or all illegal aliens, including the so-called Dreamers and their families, from enforcement action.

What are the Arguments Made by Sanctuary Advocates?

The arguments have several distinct but interrelated themes:

- Police cooperation with immigration agents erodes trust between immigrants and authorities, and causes immigrants to refrain from reporting crimes;

- We don’t want to act as immigration agents;

- We don’t get reimbursed for incarceration costs;

- Cooperation is voluntary;

- Detainers must be accompanied by warrants;

- States are sovereign entities that have the right to make their own decisions on immigration.

In our view, when examined critically none of these arguments holds water, except for the one having to do with warrants, and that argument holds only to a certain degree, which we will discuss further below.

Police cooperation compromises community trust and safety. One of the most common reasons offered for non-cooperation policies is that they are needed so that immigrants will have no fear of being turned over for deportation when they report crimes. This frequently-heard claim has never been substantiated, and in fact has been refuted by a number of reputable studies. Not a shred of evidence of a “chilling effect” on immigrant crime reporting when local police cooperate with ICE exists in federal or local government or police data or independent academic research.

It is important to remember that crime reporting can be a problem in any place, and is not confined to any one segment of the population. In fact, most crimes are not reported, regardless of the victim’s immigration status or ethnicity. According to the Bureau of Justice Statistics (BJS), in 2015, only 47 percent of violent victimizations, 55 percent of serious violent victimizations, were reported to police. In 2015, the percentage of property victimizations reported to police was just 35 percent.13 These rates have been unaffected, either by changes in the level of interaction between local and federal enforcement from 2009-2012 (which coincides with the implementation of the Secure Communities biometric matching program) or by the spread of sanctuary policies since 2014.

Data from BJS show no meaningful differences among ethnic groups in crime reporting. Overall, Hispanics are slightly more likely to report crimes than other groups. Hispanic females, especially, are slightly more likely than white females and more likely than Hispanic and non-Hispanic males to report violent crimes.14 This is consistent with academic surveys finding Hispanic females to be more trusting of police than other groups.15

A multitude of other studies refute the notion that local-federal cooperation in immigration enforcement causes immigrants to refrain from reporting crimes:

- A major study completed in 2009 by researchers from the University of Virginia and the Police Executive Research Forum (PERF) found no decline in crime reporting by Hispanics after the implementation of a local police program to screen offenders for immigration status and to refer illegal aliens to ICE for removal. This examination of Prince William County, Virginia’s 287(g) program is the most comprehensive study to refute the “chilling effect” theory. The study also found that the county’s tough immigration policies likely resulted in a decline in certain violent crimes.16

- The most reputable academic survey of immigrants and crime reporting found that by far the most commonly mentioned reason for not reporting a crime was a language barrier (47 percent), followed by cultural differences (22 percent), and a lack of understanding of the U.S. criminal justice system (15 percent) — not fear of being turned over to immigration authorities.17

- The academic literature reveals varying attitudes and degrees of trust toward police within and among immigrant communities. Some studies have found that Central Americans may be less trusting than other groups, while others maintain that the most important factor is socio-economic status and feelings of empowerment within a community, rather than the presence or level of immigration enforcement.18

- A 2009 study of calls for service in Collier County, Fla., found that the implementation of the 287(g) partnership program with ICE enabling local sheriff’s deputies to enforce immigration laws, resulting in significantly more removals of criminal aliens, did not affect patterns of crime reporting in immigrant communities.19

- Data from the Boston, Mass., Police Department, one of two initial pilot sites for ICE’s Secure Communities program, show that in the years after the implementation of this program, which ethnic and civil liberties advocates alleged would suppress crime reporting, showed that calls for service decreased proportionately with crime rates. The precincts with larger immigrant populations had less of a decline in reporting than precincts with fewer immigrants.20

- Similarly, several years of data from the Los Angeles Police Department covering the time period of the implementation of Secure Communities and other ICE initiatives that increased arrests of aliens show that the precincts with the highest percentage foreign-born populations do not have lower crime reporting rates than precincts that are majority black, or that have a smaller foreign-born population, or that have an immigrant population that is more white than Hispanic. The crime reporting rate in Los Angeles is most affected by the amount of crime, not by race, ethnicity, or size of the foreign-born population.21

- Recent studies based on polling of immigrants about whether they might or might not report crimes in the future based on hypothetical local policies for police interaction with ICE, such as one recent study entitled “Insecure Communities”, by Nik Theodore of the University of Illinois, Chicago, should be considered with great caution, since they measure emotions and predict possible behavior, rather than record and analyze actual behavior of immigrants.22 Moreover, the Theodore study is particularly flawed because it did not compare crime reporting rates of Latinos with other ethnic groups.

For these reasons, law enforcement agencies across the country have found that the most effective ways to encourage crime reporting by immigrants and all residents are to engage in tried and true initiatives such as community outreach, hiring personnel who speak the languages of the community, establishing anonymous tip lines, and setting up community sub-stations with non-uniform personnel to take inquiries and reports – not by suspending cooperation with federal immigration enforcement efforts. Proposals to increase ICE-local cooperation, such as the Davis-Oliver Act, which was passed by the House Judiciary Committee in 2015, enjoy strong support among law enforcement leaders across the country. These leaders — sheriffs, police, and state agency commanders — routinely and repeatedly express concern over crime problems associated with illegal immigration and routinely and repeatedly express their willingness to assist ICE, and that it is their duty to assist ICE.23 The National Sheriffs Association and numerous individual sheriffs and police chiefs have endorsed the Davis-Oliver Act.

Instead of pushing sanctuary policies, advocates for immigrants in the community should be stressing that victims and witnesses are never targets for immigration enforcement (unless they, too, are criminals). If immigrant advocates would help disseminate this message, instead of spreading the myth that immigrants have something to fear from interaction with local police, then everyone in the community would be safer. It is important to remember that much of the crime inflicted on aliens comes from other aliens—for instance, coyotes, drug dealers, gangbangers and other career criminals—who prey on their own communities. When this is the case, alien victims and witnesses, significantly including aliens illegally in the United States, have every reason to want them plucked out of their midst by local law enforcement and removed by ICE.

What is more, aliens tend to be very familiar with the workings of immigration law, much more so than the average citizen, because it is in their interest to do so. As such, while they may not be able to cite specific visa categories, they are quite likely to know that immigration law and policy actually contain provisions to protect victims and witnesses from removal actions so that they can provide key information to police and prosecutors. If police officers want to be able to help immigrants who are victimized to take advantage of these programs, they need to have a good working relationship with ICE – and they also need to be allowed to inquire about immigration status so that they can offer this protection.

Lastly, we should point out that while state and local governments can’t point to any credible studies to support their argument that cooperation with ICE diminishes trust levels in ethnic and alien communities, there is plenty of empirical, and powerful anecdotal, evidence which shows the damage done to communities when alien offenders are inappropriately released back to the street, whether by state and local police or by ICE, rather than being detained and removed from the United States for their offenses.24 There have been so many victims of criminal behavior by illegal aliens that surviving family members of those killed have banded together to draw attention to their plight, and to the danger posed by sanctuary policies.25 The families of these victims have been steadfastly ignored by law enforcement organizations and governments engaged in sanctuary policies, and they were ignored by the Democratic party during the presidential campaign. (Even before that, one Democratic representative went so far as to refer to the murder of a young woman by a multiply deported illegal alien felon as “a little thing”.26) But the families of the victims were not ignored by presidential candidate Trump; he embraced them publicly, and they appeared frequently with him on the campaign trail as he promised to address the problem of sanctuaries if elected.

Refusal to act as immigration agents. Much of the controversy surrounding sanctuary policies has to do with state and local law enforcement agencies refusing to honor immigration detainers filed by ICE agents against aliens arrested for criminal offenses, aliens whom the agents have determined to be deportable and intend to take custody of, once state or local criminal justice proceedings are done. The detainer is a notification to the arresting/holding agency of ICE’s intention to assume custody.27

Many state and local agencies complain that by being asked to honor the detainer, they are being forced to act as surrogate immigration officials. This belies the fact that when ICE agents file detainers against an individual in police custody, they have already made determinations about his alienage and deportability. They are not asking the police either to render that judgment on their own, or to second-guess their decision-making. For this reason, state and local agencies are not being asked to act as immigration agents; they are simply expected to tender to the federal authorities the individual identified in the detainer.

What is more, the reality of sanctuaries is that there are many variations on the theme: a number of jurisdictions make decisions about whether to honor a detainer based on the crimes for which an alien has been charged or convicted. When they do this, they are effectively substituting their judgment for federal statutes which make clear the offenses that render an alien to be deportable, and so it is dishonest and deceptive for such jurisdictions to complain about acting as surrogates. They have already done so—and done it in a way that is contrary to law.

Reimbursement for incarceration costs. Many jurisdictions complain that it costs them hundreds of thousands (sometimes millions) of dollars each year arresting, prosecuting, and incarcerating deportable aliens, or holding them for additional time (up to 48 hours) on an ICE detainer. They charge that, in turn, they get reimbursed for only a portion of those costs, usually via the State Criminal Alien Assistance Program (SCAAP). They ask, then, why they should honor immigration detainers. It is worth observing, though, that the amounts being disbursed are significant. In 2015 more than $165,342 million was disbursed to state, county, and city law enforcement entities—including to sanctuary cities that thumb their nose at federal immigration agents and provide no cooperation whatever, or actively impede enforcement efforts.28

But putting aside the millions of dollars being disbursed, there are at least three additional, obvious, flaws in this train of logic.

- First, although control of immigration is in fact a federal responsibility—and one which the Obama administration has been notoriously reluctant to embrace—it does not follow that the federal taxpayer should be on the hook for the entire cost of locking up aliens who are arrested and charged with state crimes, especially if state or local policies encourage or tolerate illegal settlement.

- Second, if the complaint of non-cooperating jurisdictions is that the federal government has substantially failed in its job of keeping aliens from illegally crossing the border and in preventing aliens from overstaying their visas, thus resulting in increased numbers of alien criminals and heavier burdens for state and local law enforcement, then how does it follow that the solution is to release these aliens onto the street and back into the community rather than give custody of them over to federal agents to remove them, once the state criminal justice proceedings have concluded? Where is the logic in that?

- Third, many state and local law enforcement agencies report that cooperating in the removal of criminal aliens actually saves the community significant sums of money. As is the case with other offenders, criminal aliens are prone to re-offend (at rates comparable to native-born criminals). When criminal aliens are removed instead of returned to the community, the community is spared the cost of their future crimes and the associated costs of incarceration and supervision, not to mention the pain and trauma of future victims.

The previously-referenced OIG report mentioned ICE’s view that, until there is further clarification that cooperation with federal immigration authorities is obligatory, then state and local governments can get away with refusing cooperation on budgetary grounds. Indeed, many of the sanctuary policies specify that no funds may be expended to assist the federal government in immigration enforcement. Yet in some cases, notably Cook County, Illinois, when ICE has offered to repay the cost of any additional time in custody for the criminal alien, the county did not accept the offer, which makes clear that cost was not the real reason for the sanctuary policy.

Cooperation is voluntary. This argument is closely aligned with the prior discussion about detainers, as well as the discussion that follows regarding states’ rights. The “cooperation is voluntary” argument suggests that state and local agencies may choose whether or not they cooperate with federal immigration authorities—usually, in relation to ICE and its detainers. The Obama administration has given power to this argument by public pronouncements to this effect from one of its senior ICE officials; pronouncements made, we note, with no legal justifications to support them that we can determine.29 Moreover, the Priority Enforcement Program (PEP) implemented in November 2014 as part of a large set of executive actions explicitly allows local jurisdictions to ignore ICE attempts to gain custody of a criminal alien in their custody, and allows local jurisdictions to dictate to ICE which criminal aliens will be subject to enforcement.30

When considering the validity of the pronouncement that honoring of detainers is voluntary, it is well to keep in mind that the Obama administration made a similar argument about whether or not state and local governments were obliged to cooperate with the biometric matching that forms the heart of the successful Secure Communities program—an argument it was later forced to admit was untrue and which had no factual basis in the law, although it repeatedly made the assertion until events forced them to backtrack on their prior assertion.31

What is more, the suggestion that honoring detainers is voluntary, or in some way optional, defies the ordinary practices, procedures, and expectations of all other federal, state, and local agencies where detainers are concerned. When other agencies file detainers, they fully expect them to be honored. Imagine, if you will, the United States Marshals Service suggesting that a detainer which it files with state or local law enforcement agencies is “voluntary”—it’s unthinkable.

Some have said that the fundamental difference is because immigration detainers are issued by administrative authorities, as opposed to judges. This flies in the face of reality: parole boards are administrative authorities, yet parole officers routinely file detainers to take back into custody parole violators, which detainers are uniformly honored. So, too, with military police authorities who file detainers to take into custody soldiers or sailors who have deserted or are absent without leave, when they are arrested by police? Should these detainers be rejected by state or local governments because, hypothetically, they disagreed with laws under which the offender was convicted and paroled, or with the federal government’s wars in Iraq or Afghanistan? Again, unreasonable.

In any case, questioning the issuing authorities is beyond the purview of state or local officials. Immigration officials who issue detainers (and, in fact, even warrants for the arrest of aliens in removal proceedings) are indeed administrative officials—but so are immigration judges who hear the deportation cases. All of them are the individuals who have been given the authority under the laws passed by Congress and signed into law by various presidents which, under the federal preemption and supremacy doctrines (discussed below), puts them uniquely within the purview of the federal government. That state and local governments like or agree with the statutory scheme is neither here nor there.

Detainers must be accompanied by warrants. Several sanctuary jurisdictions have indicated that they will honor detainers only when accompanied by warrants. The nature of the warrant has not been specified in many jurisdictions, but a few have been clear that what they are looking for is a judicial warrant.

The argument behind this approach is that a detainer, in and of itself, does not reflect the probable cause needed to justify detention and arrest.32 We believe that this argument is beyond the scope of state or local jurisdictions to assert, because it is not their business to stand behind immigration agents looking over their collective shoulder, rendering legal determinations on the adequacy of their work—such a notion flies in the face of federal supremacy in the matter of immigration (see our discussion below, under “States rights”).

What is more, federal law very clearly provides for arrest of an alien believed to be illegally in the United States without warrant by a federal officer when “he has reason to believe that the alien so arrested is in the United States in violation of any such law or regulation and is likely to escape before a warrant can be obtained for his arrest”.33 Often when immigration agents file detainers with police, sheriffs, and jails, they don’t know how quickly the alien may be released from custody on bond or on order of a presiding judge or magistrate, and time is of the essence. The exigency will depend in large measure on how many hours have elapsed between the initial arrest of the alien by police and when ICE officers become cognizant of the arrest. If it has been a substantial period of time, they may seek to stay that release with a detainer long enough to be able to follow up afterward with additional charging documents, such as a warrant of arrest in immigration proceedings, and ultimately assume custody.

However, we understand that open borders and migrant advocacy groups have been aggressively litigious in recent years, and that the Obama administration has exhibited a disturbing tendency to leave its “law enforcement partners”, as they are wont to describe state and local enforcement agencies, in the lurch when lawsuits over detainers have been filed34 (something we believe is less likely to occur with a President Trump and an Attorney General Sessions in office).

For this reason, there is the potential for compromise within certain boundaries, where jurisdictions insist on warrants. But to be specific, the warrants we describe are not judicial warrants. There are no judicial warrants available to immigration agents when seeking to arrest an alien and charge him in removal proceedings for being in the United States in violation of law.

The only judicial warrants available to immigration agents would be those obtained to criminally prosecute an alien, for instance if he has unlawfully reentered the United States after deportation, or if he has committed some kind of fraud, or the like. Thus when sanctuary jurisdictions demand a judicial warrant to accompany a detainer filed in civil removal proceedings, they either have no idea what they are insisting upon—or they do, and they know such a demand, being impossible to meet, will obstruct the arrest and deportation of illegal aliens, including aliens who have been arrested, prosecuted, and convicted by state and local authorities for crimes. Of course, this results in such criminals being released back into the community to reoffend, often with horrendous consequences.

When state or local jurisdictions ask ICE to accompany detainers with copies of a warrant, but don’t insist on it being a judicial warrant, this is the area in which compromise is possible. The Immigration and Nationality Act provides that “On a warrant issued by the [Secretary of Homeland Security], an alien may be arrested and detained pending a decision on whether the alien is to be removed from the United States”.35

To be clear, this provision of law refers to a civil warrant issued by federal immigration officers who have been delegated authority flowing from the Secretary. Thus, when jurisdictions seek to protect themselves from the possibility of tort litigation by asking for warrants then, absent exigent circumstances, the prevailing ICE policy should be to accommodate the request by concurrently filing with the detainer an administrative warrant (form I-200) or, if the alien is already a fugitive from deportation proceedings against whom a final order of removal is outstanding, then a warrant of removal (form I-205).

However, it is important to emphasize that decisions about which deportable aliens to take custody of and initiate deportation proceedings against must always be a federal decision and not left to the discretion of state and local governments, which have no constitutional role in that process.

The Suffolk County Solution. The practice of issuing administrative warrants along with the detainer is precisely the solution that has been worked out in Suffolk County on Long Island, New York. In September of 2014, Sheriff Vincent DeMarco was told by county officials that the county would no longer indemnify his department against lawsuits instigated by anti-enforcement advocacy groups if he continued to comply with ICE detainers.

Following the deployment of Secure Communities fingerprint-matching in Suffolk County in February of 2011, ICE had been able to increase the deportations from Suffolk County jails by 60 percent. Suffolk County cases represented nearly 20 percent of the criminal alien deportation workload for the New York City ICE field office, so this was a hard blow to immigration enforcement in the area, not to mention its detrimental effect on community safety.

The enforcement disruption came just at the time when communities in Suffolk County had begun to experience the arrival of hundreds of illegal alien youths from Central America, including many who were involved with MS-13, the violent transnational street gang dominated primarily, but not exclusively, by members from El Salvador.

Despite pressure from advocacy groups to bar ICE from the jail and cease communicating with ICE, Sheriff DeMarco continued to cooperate with them in other ways, and complied with all ICE requests for notification of the release of any deportable aliens in custody at the jail. Still, a number of criminal aliens fell through the cracks and had to be released instead of being held and turned over to ICE for deportation proceedings.

Inexplicably, while this was playing out, ICE failed to inform Sheriff DeMarco that the Supreme Courts of New York, sitting in two neighboring counties, had decided in two different cases in 2014 and 2015 (People vs. Xirum and Josue Chery v Sheriff of Nassau) that holding an alien on an ICE detainer after a finding of probable cause is entirely permissible and is not a violation of the alien’s civil rights. Said the court in Xirum:

“this court cannot say that under a Fourth Amendment analysis it is unreasonable for the [county Department of Corrections] to further hold a defendant for at most 48 hours as requested in the Detainer after the conclusion of the state case in order to give DHS an opportunity to seize the subject of the deportation order.”

Further:

“Similar to the fellow officer rule that permits detention by one police officer acting on probable cause provided by another, the DOC had the right to rely upon the very federal law enforcement agency charged under the law with ‘the identification, apprehension, and removal of illegal aliens from the United States.’”

Meanwhile, the number of new illegal alien youth arrivals from Central America doubled, and violence attributed to MS-13 and some of the youths affiliated with the gang significantly escalated. Since 2014, there have been at least seven murders attributed to MS-13 in just one Suffolk County town (Brentwood), including the slaying of two 16 year-old girls not involved with the gang.36

After meeting with local lawmakers concerned about the public safety implications of the forced sanctuary policy, and after learning that New York courts had held that there were no legal obstacles to a fully cooperative policy, Suffolk County reversed its position. Sheriff DeMarco was able to secure an agreement from ICE to issue administrative warrants of arrest or removal to accompany the detainers, and announced an end to the sanctuary policy on December 5, 2016.

States have the sovereign right to choose sanctuary policies. Much of the argument devolving around the obligation to honor immigration detainers, and otherwise cooperate with federal immigration authorities surrounds the issue of states’ rights. This argument derives from the Tenth Amendment to the Constitution, which states that “The powers not delegated to the United States by the Constitution, nor prohibited by it to the States, are reserved to the States respectively, or to the people.”37

It is true that the Constitution preserves only a select few powers to the federal government—powers which, if left to the states, might very result in an unraveling of our republic. However, among those reserved powers are foreign policy, interstate and foreign commerce and, most specifically relevant to the issue at hand, immigration.38 This fundamental fact would seem to foreclose the argument that states (or their political subdivisions) can pick and choose from among the federal immigration statutes they wish to see enforced, while frustrating the remainder by refusal to cooperate with federal efforts.

Imagine, if you will, a state insisting that it had the right to establish its own foreign policy and decided to initiate “diplomatic” ties with North Korea. Or imagine that a state or one of its political subdivisions decided that it could not support a trade embargo established by the federal government, and therefore began trade negotiations with the renegade nation? Is there any doubt that the federal government would squelch any such an initiatives at their first inception and land on the backs of the intransigent state and local officials with very heavy boots? Yet this is exactly what has transpired with immigration law and policy in the last few years.

Many readers are probably aware that “states’ rights” as embodied by the Tenth Amendment (the argument being used by sanctuary apologists today) was one of the principle arguments made by rebellious states which attempted to secede from the Union to form the Confederacy.39 We are neither the first nor the only ones to note that irony.40 There is something perverse about so-called progressives using a neo-Confederate states’ rights argument to avoid meeting their responsibilities under the law, which includes acknowledging federal supremacy on the subject of immigration. Some on the ultra left have even gone so far as to urge California’s secession from the United States (often referred to as “Calexit”).41

Make no doubt, we believe in states’ rights—the right, for instance, of individual states to enact laws that support, and are consonant with, federal efforts at controlling illegal immigration in order to safeguard their own communities and preserve their limited resources for persons lawfully present. But in the topsy-turvy world of the Obama administration, those were the efforts that resulted in lawsuits and injunctions, while sanctuary jurisdictions have been left untouched to fester and grow.

We see sanctuary policies as nothing more, and nothing less, than a “nullification of law” effort much akin to past attempts by some states to defy federal integration policies in the field of civil rights—only this time, because the policy underlying the nullification argument is fashionable among open borders elitists, they choose to clothe it in other garb. This is unconscionable, and it is a situation that Donald Trump has vowed to change.

How can the New Administration Tackle Sanctuaries?

There are a number of options available to the new administration in order to begin the process of dismantling sanctuaries and restoring a clear understanding of federal supremacy in immigration matters, where state and local governments, and even universities public or private, are concerned:

- Rescinding “prosecutorial discretion” and “priority enforcement program” policies;

- Restoring effective alien criminal identification programs and technology;

- Defunding of federal monies now pouring into sanctuary states and local governments;

- Decertifying various authorizations, such as the ability to enroll foreign students on campuses that declare themselves to be sanctuaries;

- Initiating civil litigation to enjoin obstructive laws or policies;

- Criminally prosecuting the most egregious cases of harboring and shielding criminal illegal aliens from ICE by state or local government agencies; and

- Issuing administrative warrants to accompany detainers.

It’s important to recognize that dismantling state and local government sanctuaries also requires attending to, and eliminating, those factors at the federal level that have contributed to the creation and expansion of sanctuaries during the last several years.

Rescinding “prosecutorial discretion” and “priority enforcement program” policies. In the past several years, the Obama administration has overseen the implementation of a significant number of policy memoranda and binding guidance that tie the hands of immigration agents and trial attorneys trying to go about the business of arresting, litigating against, and removing illegal aliens, including most especially alien criminals.42

All of these policy documents have been based on the argument that finite resources require prioritizing which aliens merit investigative and prosecutorial attention. But what they have actually done is effectively eviscerate immigration enforcement by virtually any measure one might choose to use: the number of detainers permitted to be filed against aliens in police custody; the number of aliens arrested by ICE; the incredible number of aliens inappropriately released and now on the streets of American cities, many of them under unexecuted final orders of removal; and historic lows in the number of removals.

When we hear of the “broken immigration system” we are repeatedly reminded that it is dysfunctional in great measure because this administration has willfully and deliberately chosen to undermine it. In our view, the first order of business for the new leadership at DHS must be to rescind these policies and make clear that ICE agents and prosecutors are free within the boundaries of the law to pursue their mission.

Restoring effective criminal alien identification programs and technology. When DHS secretary Jeh Johnson issued his series of November 2014 executive actions, which significantly impinged on the already weakened interior enforcement structure, he directed the end of the Secure Communities (SC) program, which had proven itself an effective and efficient means of obtaining near-realtime information about criminal arrests of aliens nationwide, so that agents could follow up by filing detainers and taking custody of the aliens at the earliest opportunity. He substituted instead the Priority Enforcement Program (PEP), which has proven itself a failure by even further hamstringing the agents.43 PEP must be rescinded and SC reinstituted.

Even before that, DHS and ICE leaders had taken steps to cripple another extremely successful enforcement program called “287(g)” after the provision in the INA on which it is based. The 287(g) program provides for delegation of authority to state and local enforcement officers so that if, in the course of their own patrol or jail duties, they encounter situations having obvious immigration implications (for instance, state police encountering alien smuggling loads on interstate highways), they could act as immigration officers in order to secure the aliens, transport them, and even process them if needed, until ICE agents could arrive.44 Importantly, the 287(g) program also provided those state and local officers with immunity to the same extent as is enjoyed by federal officers. The 287(g) program should be resuscitated and invigorated so that there are the greatest possible number of state and local agencies participating nationwide.

Taking the above steps will go far toward restoring a balance in tone and approach on the part of the federal government clearly reflecting its own commitment to fair but vigorous enforcement in the interior of the United States.

From here on, we focus on what actions may be taken against state and local sanctuary governments. Although they may be perceived as a hierarchy of actions that rise in level of severity, it’s important to note that nothing requires them to be used sequentially; they could potentially be used all at once, or in any combination, as the occasion, jurisdiction, or circumstance require.

Publish Information on Criminal Releases. One of the Trump administration’s first moves to address the sanctuaries should be to provide the public with more information on the practical effect of these policies. ICE should be directed to publish a weekly list of details about the criminal aliens who are freed by the sanctuaries, including criminal histories. In addition, where possible, the victims should also be notified.

The list should be known as “Denny’s List,” named for Dennis McCann, who was killed by an illegal alien in Chicago in 2011, who ran over him while driving drunk, just months after completing probation for a prior aggravated drunk driving conviction. The illegal alien, Saul Chavez, was released within weeks after Cook County adopted one of the most extreme sanctuary policies in the country. Chavez fled to Mexico and has never faced charges for McCann’s death.

Defunding. One of the quickest, most obvious ways to get the attention of state and local authorities is via the power of the purse. Tens of millions of dollars are given away in various grant programs yearly. Withholding of these funds would make a serious dent in the budgets of state and local agencies. This can, for the most part, be done without the need for new legislation because federal rules already require that grant funding applicants be in conformance with all federal laws before they can be found eligible to receive funds. As discussed above, the most applicable and relevant section of the law is 8 U.S.C. 1373.45

This was always a tool available to the Obama administration, which opted not to use it until recently when Rep. Culberson made clear that he would hold back Department of Justice (DOJ) funding unless DOJ, in turn, began forcing compliance and withholding Bureau of Justice Assistance (BJA) monies from sanctuary jurisdictions. That, of course, got the attention of the attorney general.46

On July 7, 2016, DOJ released updated guidelines that disqualify sanctuary jurisdictions from receiving DOJ law enforcement funding if they are found to be in violation of 8 U.S.C. 1373, among other laws. All state and local agencies were told that they would have to attest to compliance with the law as a part of the application process. According to the revised guidance:

“If the applicant is found to be in violation of an applicable federal law by the OIG, the applicant may be subject to criminal and civil penalties, in addition to relevant OJP programmatic penalties, including suspension or termination of funds, inclusion on the high risk list, repayment of funds, or suspension and debarment.”

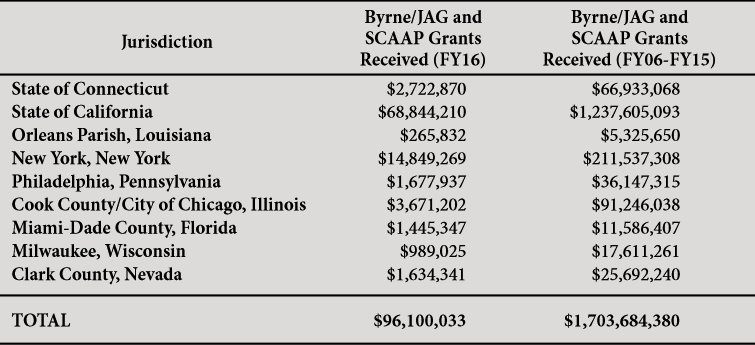

The affected programs administered by BJA include SCAAP, and Byrne JAG and possibly other grants. They were told that they had until June 30, 2017 to change their sanctuary policies to avoid running afoul of federal law.

Nonetheless the 10 jurisdictions investigated by the Inspector General still received about $96 million in grants for 2016. It remains to be seen whether they will change their position by the looming deadline or new policies or actions to be taken by the Trump administration. So far, Philadelphia, Chicago, and New York City, among others, have announced that they intend to keep their sanctuary policies despite notification from DOJ that they are inconsistent with the law.

The table below lists the 10 jurisdictions that are on notice and the amount of funding that they could potentially have to return if they are found to be non-compliant.

There are additional programs containing substantial pots of money that could be withheld from obstructionist jurisdictions, such as the various homeland security grant programs administered by DHS, which are provided to state, county, and city governments all over the nation (in 2015, DHS disbursed more than $1.044 billion to state and local jurisdictions under its extensive grant programs47). DHS is, after all, the primary cabinet department charged with defending America’s borders and enforcing its immigration laws. Why should it continue to provide funds to scofflaw governments who by their sanctuary actions make the country, and their own communities, significantly less safe?

Another area ripe for consideration is the Department of Defense program which provides military surplus vehicles, equipment, and supplies to state and local law enforcement agencies for little or nothing.

Depending on the level of intransigence, a Trump administration might even consider withholding community development and community services block grants to sanctuary jurisdictions. These are programs administered by the federal Departments of Housing and Urban Development and Health and Human Services, respectively.

Such a move could be justified on the grounds that sanctuary policies encourage illegal settlement, thereby increasing the number of people who need costly social and educational services and who are not contributing significantly to tax revenues.

Decertification. Almost all public and private universities seek approval from DHS to permit foreign students and exchange visitors to attend their institutions. This permits them to issue the forms that potential students and exchange scholars need to present to American consular officers in order to obtain the required visas for entry.48 They do this for reasons of prestige and, not least, money: foreign students are a ready source of revenue because they usually pay much higher tuition rates than citizen or resident alien students. Such a constant and reliable stream of money can make the difference between solvency and the need to raise tuition rates across the board.

It is an irony that even as most institutions of higher learning seek and obtain DHS approval to enroll the foreign students and exchange visitors, many have a policy of permitting illegal aliens to attend classes, often at subsidized in-state tuition rates or with targeted scholarship or tuition waiver programs, even if they don’t make any public announcements that they are pursuing official sanctuary non-cooperation policies, such as the University of California system we described earlier.

The answer to this conflicting and oxymoronic policy is self-evident. DHS need only implement a policy to decertify any and all institutions with sanctuary policies, official pronounced or not, and deny them the opportunity to enroll foreign students and exchange visitors until they mend their ways.

Decertifying sanctuary institutions from the list of schools approved to receive foreign students should also be coupled with a loss of research and other federal funding dollars, such as the university-based centers of excellence administered by DHS49, or the Department of Education’s Fund for the Improvement of Post-Secondary Education (FIPSE). The denial of such grants has been used in the past to incentivize certain behavior; for instance, schools that bar military recruiters from campus are prohibited from receiving FIPSE awards. It seems to us appropriate to take the same course of action to curb obstruction of federal immigration laws.

The Trump administration may also wish to initiate the practice of refusing to provide Pell grant or other tuition monies to students who enroll in sanctuary institutions, thus forcing them to choose schools whose policies are more in line with the requirements of federal immigration law.

Civil Litigation. The Trump administration should consider filing lawsuits against sanctuary jurisdictions and seek to enjoin laws, regulations, policies, and operating instructions in those jurisdictions that obstruct proper and effective enforcement of the nation’s immigration laws. We recognize that even the federal government has finite resources and not all sanctuary governments will likely be sued, no matter how richly deserving, but the obvious place to start would be the most egregious, perhaps defined as the jurisdictions that free the most criminal aliens who are subject to ICE detainers. Reportedly, the following five large sanctuary jurisdictions are refusing to cooperate with ICE in any way whatsoever: San Francisco, California; Cook County, Illinois; Contra Costa County, California; Santa Clara County, California; and King County, Washington.

The previously-mentioned provisions of federal law that proscribe any government entity from prohibiting or impeding communication of its employees to or from federal authorities regarding an alien’s status in the United States is a good starting point to initiate such injunctive action. It’s worth noting that while these provisions are particularly pertinent to exchanges of information between ICE and state and local law enforcement agencies for the purpose of identifying and apprehending alien criminals, on their face they apply to any government agency, including for instance state motor vehicle departments, as well as state-supported university and college systems.

Criminal Prosecution. Several sanctuary jurisdictions appear to us to have crossed the line with their conduct and activities into criminal behavior, as well as potentially leaving themselves open to civil lawsuits filed by victims or surviving family members of individuals killed or harmed by illegal aliens.50

The murder of Kate Steinle in San Francisco is one example. In that case, the multiply-deported alien criminal was actually turned over to local enforcement authorities by ICE after having been apprehended by its agents. He was tendered to local authorities on the basis of an outstanding criminal warrant, which was later dismissed by the District Attorney. The San Francisco County Sheriff, however, refused to return custody of the alien to ICE, citing sanctuary noncooperation policies as his rationale—even though he had received the prisoner from ICE to begin with. Instead, the alien was released onto the streets of the community, only to murder Ms. Steinle a short time afterward. While the sheriff later lost his reelection bid, it seems to us that he ought to have been prosecuted for his actions. Equally outrageous, though, was the inexplicable Obama White House assertion that Steinle’s death could have somehow been avoided had “comprehensive reform” (meaning a general amnesty) been enacted.51

The relevant law is a federal felony statute that prohibits “harboring and shielding from detection” aliens in the U.S. in violation of law. The statute applies to governmental officials as readily as it does to employers, private citizens or even corporations.52 Using this criminal statute seems to us an appropriate remedy in egregious cases such as that of Ms. Steinle (and, frankly, a host of others that have occurred in recent years, the stories of many of whom can be found on the Remembrance Project website previously mentioned) to ensure that state and local officials understand the seriousness with which the federal government is going to take their intransigence and obstruction.

Using the harboring and shielding statute as a tool to dismantle sanctuaries was item 50 in the series of recommendations we at the Center made in a backgrounder published this past April, “A Pen and a Phone: 79 immigration actions the next president can take.”53

Conclusion

Mr. Trump has announced that he would nominate Senator Jeff Sessions as his attorney general. During his tenure in the Senate, Mr. Sessions has been an unapologetic advocate of immigration enforcement, and a steadfast believer that immigration policies should serve the national interest and the interests of ordinary Americans. As the attorney general, Sen. Sessions, working with the new DHS secretary, will have the legal mechanisms at his disposal to tackle sanctuaries on every front.

It is clear that a showdown is coming. What form it will take remains to be seen.

End Notes

1 See, for instance, Mark Krikorian, “No Sanctuary for Sanctuary Cities”, Center for Immigration Studies (CIS) blog, Feb. 25, 2009; https://cis.org/krikorian/no-sanctuary-sanctuary-cities and W.D. Reasoner, “Which Way, New York?” CIS blog, Oct. 2011. https://cis.org/nyc-local-interference

2 Article II, Section 3 of the United States Constitution requires that “[The President] shall take Care that the Laws be faithfully executed....” See, e.g.,“The Heritage Guide to the Constitution” http://www.heritage.org/constitution/articles/2/essays/98/take-care-clause.

3 For an interactive map of existing sanctuary locations, see Bryan Griffith and Jessica Vaughan, “Map: Sanctuary Cities, Counties, and States: Sanctuary Cities Continue to Obstruct Enforcement, Threaten Public Safety” CIS backgrounder, orig. Jan. 2016, updated Aug. 31, 2016. https://cis.org/Sanctuary-Cities-Map

4 Associated Press, “Mayor Rahm Emanuel says Chicago will remain sanctuary city for immigrants” The Herald News, Nov. 14, 2016 http://www.theherald-news.com/2016/11/14/mayor-rahm-emanuel-says-chicago... ; David Goodman, “ ‘The Ball’s in His Court,’ Mayor de Blasio Says After Meeting With Trump”, New York Times, Nov. 16, 2016 http://www.nytimes.com/2016/11/17/nyregion/donald-trump-mayor-bill-de-bl... ; Neil W. McCabe, “Mayor Trolls President-elect Trump: Take Our Federal Funds, We Will Stay a Sanctuary City Forever”, Breitbart.com, Nov. 21, 2016. http://www.breitbart.com/big-government/2016/11/21/mayor-trolls-presiden... take-our-federal-funds-we-will-stay-a-sanctuary-city-forever/

5 See, for example, the statements made by the Los Angeles Police Department Chief: “Chief Beck: LAPD Will Not Aid Trump Deportation Efforts”, Police Magazine, Nov. 15, 2016. http://www.policemag.com/channel/pa trol/news/2016/11/15/chief-beck-lapd-will-not-aid-trump-deportation-efforts.aspx

6 Mark Davis, “Malloy says he’ll sue if Trump attempts to punish ‘Sanctuary City’ New Haven”, News8 WTNH online, Nov. 22, 2016. http://wtnh.com/2016/11/22/malloy-says-hell-sue-if-trump-attempts-to-pun...

7 Edmund Kozak, “Students Rage for ‘Sanctuary’ Campuses: Fearful of Trump, college agitators demand colleges become safe spaces for illegal aliens” Lifezette online magazine, updated Nov. 17, 2016. http://www.lifezette.com/polizette/students-rage-sanctuary-campuses/ and John Binder, “Vanderbilt Students Demand ‘Sanctuary Campus’”, Breitbart.com, Nov. 28, 2016. http://www.breitbart.com/texas/2016/11/28/vanderbilt-students-demand-san...

8 “President Wim Wiewel declares PSU a sanctuary university”, press announcement, Portland State University website, Nov. 18, 2016. http://www.pdx.edu/news/president-wim-wiewel-declares-psu-sanctuary-univ...

9 Blake Neff, “Columbia University Declares Itself a Sanctuary Campus for Illegal Immigrants”, The Daily Caller, Nov. 21, 2016. http://dailycaller.com/2016/11/21/columbia-university-declares-itself-a-...

10 “Undocumented Student Resources”, University of California website, accessed on December 2, 2016. http://undoc.universityofcalifornia.edu/

11 Memorandum from Michael E. Horowitz, Inspector General, “Department of Justice Referral of Allegations of Potential Violations of 8 USC 1373 by Grant Recipients,” May 31, 2016, https://oig.justice.gov/reports/2016/1607.pdf.

12 With regard to the potential penalty, note, though, that the statute says, “in the case of a violation...resulting in the death of any person, be punished by death or imprisoned for any term of years or for life, fined under title 18, or both.” An extreme reading of the statute might lead one to conclude that the actions of the San Francisco sheriff in releasing a multiply-deported alien felon which in turn led him to murder of Kate Steinle (discussed later in the body of this report) would subject him not only to prosecution but punishment under this enhancement of the available penalties.

13 Jennifer Truman, Ph.D., Lynn Langton, Ph.D., and Michael Planty, Ph.D., Bureau of Justice Statistics, “Crime Victimization 2012,” http://www.bjs.gov/content/pub/pdf/cv12.pdf.

14 See additional data from the National Crime Victimization Survey here: http://www.bjs.gov/content/pub/pdf/cvus0805.pdf.

15 Lynn Langton, Marcus Berzofsky, Christopher Krebs, and Hope Smiley-McDonald, Bureau of Justice Statistics report, “Victimizations Not Reported to the Police, 2006-2010,” http://www.bjs.gov/content/pub/ pdf/vnrp0610.pdf.

16 Evaluation Study of Prince William County’s Illegal Immigration Enforcement Policy: FINAL REPORT 2010, http://www.pwcgov.org/government/dept/police/Documents/13185.pdf.

17 Robert C. Davis, Edna Erez and Nancy Avitabile, “Access to Justice for Immigrants Who are Victimized. The Perspectives of Police and Prosecutors” Criminal Justice Policy Review, 12(3): 183-196, 2001.

18 Menjivar, Cecilia and Cynthia L. Bejarano, “Latino Immigrants’ Perceptions of Crime and Police Authorities in the United States: A Case Study from the Phoenix Metropolitan Area,” Ethnic and Racial Studies 27(1): 120-148, 2004.

19 Commander Michael Williams, Collier County (Fla.) Sheriff’s Office, as reported here: http://cis.org/files/articles/2009/leaps/index.htm.

20 Boston Police Department report on calls for service by precinct provided by Jessica Vaughan.

21 Los Angeles Police Department annual Statistical Digest, available at www.lapdonline.org.

22 Nik Theodore, “Insecure Communities: Latino Perceptions of Police Involvement in Immigration Enforcement”, College of Urban Planning & Public Affairs, University of Illinois at Chicago, May 1, 2013. https://greatcities.uic.edu/2013/05/01/insecure-communities-latino-perce...

23 See for example, the remarks of sheriffs at these events by the Center for Immigration Studies: https://cis.org/Videos/Sanctuary-Cities-Panel, https://cis.org/Videos/Panel-Crime-Challenges, and https://cis.org/vaughan/sheriffs-skeptical-chilling-effect-secure-communi...

24 Jessica Vaughan, “The Non-Departed: 925,000 Aliens Ordered Removed Are Still Here” CIS backgrounder, June 30, 2016. https://cis.org/vaughan/non-departed-925000-aliens-ordered-removed-are-st...

25 See http://www.theremembranceproject.org/.

26 Mark Krikorian, “Kate Steinle Day”, CIS blog, July 1, 2016, https://cis.org/krikorian/kate-steinle-day

27 For an in-depth discussion of detainers, see Dan Cadman and Mark Metcalf, “Disabling Detainers”, CIS Backgrounder, Jan. 2015. https://cis.org/disabling-detainers

28 A spreadsheet of yearly SCAAP disbursements to each receiving location can be found on the Department of Justice Bureau of Justice Assistance website, by clicking on the “Archives” tab in the SCAAP section: https://www.bja.gov/ProgramDetails.aspx?Program_ID=86#horizontalTab8

29 Cadman and Metcalf, op. cit.

30 Jessica Vaughan, “Public Safety Impact of the Obama Administration’s Priority Enforcement Program,” testimony before the Texas Senate Subcommittee on Border Security, Mar. 23, 2016, https://cis.org/Testimony/Vaughan-Public-Safety-Impact-of-the-Obama-Admin....

31 See, for example, “ICE: Secure Communities program not optional”, Homeland Security News Wire, Mar. 7, 2011. http://www.homelandsecuritynewswire.com/ice-secure-communities-program-n...

32 The very reference to “probable cause” as the legal standard for arrests pursuant to civil removal proceedings is mistaken, because that is not the standard at play. This insistence itself reflects the many misunderstandings that prevail when state and local authorities start substituting their judgment for that of the officials responsible for enforcing the federal scheme of immigration control.

33 8 U.S.C. Sec. 1357(a)(2). https://www.law.cornell.edu/uscode/text/8/1357

34 W.D. Reasoner, “Leaving a Local Law Enforcement Partner in the Lurch: With Friends Like ICE, Who Needs Enemies?”, CIS blog, Sep. 4, 2012. https://cis.org/reasoner/leaving-local-law-enforcement-partner-lurch-fr…

35 8 U.S.C. Sec. 1226(a). https://www.law.cornell.edu/uscode/text/8/1226

36 Joseph J. Kolb, “Brentwood, NY Consumed by MS-13 Crime Wave,” CIS backgrounder, Nov. 2016, https://cis.org/Brentwood-NY-Consumed-by-MS-13-Crime-Wave.

37 The Legal Information Institute of Cornell University Law School phrases it this way: “The Tenth Amendment helps to define the concept of federalism, the relationship between Federal and state governments. As Federal activity has increased, so too has the problem of reconciling state and national interests as they apply to the Federal powers to tax, to police, and to regulations such as wage and hour laws, disclosure of personal information in recordkeeping systems, and laws related to strip-mining.” https://www.law.cornell.edu/constitution/tenth_amendment

38 Article 1, Section 8, Clause 4 states, “The Congress shall have Power...To establish an uniform Rule of Naturalization[.] http://www.usconstitution.net/xconst_A1Sec8.html The Supreme Court has ruled the federal preeminence in naturalization matters to include not just naturalization, but immigration generally, since entry of an alien into, and residence within, the United States are the precursor steps to naturalization.

39 For a topical treatment of the subject, see “States’ Rights: The Rallying Cry of Secession”, The Civil War Trust, http://www.civilwar.org/education/history/civil-war-overview/statesright...

40 See Victor Davis Hanson, “Enemies of Language”, National Review Online, Nov. 24, 2016. http://www.nationalreview.com/article/442459/language-police-liberals-se...

41 Austin Yack, “California’s Secession Movement Gains Traction After Trump’s Victory, National Review Online, Nov. 10, 2016 http://www.nationalreview.com/corner/442096/california-secession-trumps-... ; and Joel B. Pollak, “Calexit: Leftists File Papers to Secede, Form New Confederacy”, Breitbart.com, Nov. 22, 2016. http://www.breitbart.com/california/2016/11/22/calexit-leftists-file-pap...

42 An exhaustive list of the various prosecutorial discretion policy memoranda, which increasingly inhibited the ability of ICE agents to initiate arrests, and of trial attorney prosecutors to pursue removal cases can be found in an online article by Van Esser titled, “Executive Amnesty Review Promises More Twists and Turns (of the Law)”, Numbers USA, March 20 2014. The article also provides hotlinks to the documents themselves. https://www.numbersusa.com/content/nusablog/van-esser/march-20-2014/exec...

43 Vaughan, op. cit., Texas testimony.

44 Jessica Vaughan and James R. Edwards, Jr., “The 287(g) Program, Protecting Home Towns and Homeland”, CIS backgrounder, Oct. 2009. https://cis.org/287greport.

45 In addition to the prohibition against impeding communication with federal immigration authorities found in 8 U.S.C. 1373, https://www.law.cornell.edu/uscode/text/8/1373 there is a second, similar provision to be found at 8 U.S.C. 1644, https://www.law.cornell.edu/uscode/text/8/1644 although it is not cited as frequently when discussing state or local intransigence.

46 Jessica Vaughan, “House Appropriations Boss Initiates Crackdown on Sanctuaries”, CIS blog, Feb. 1, 2016 https://cis.org/vaughan/house-appropriations-sanctuaries ; and “Justice Department Agrees to End Subsidies for Sanctuaries” Feb. 25, 2016. https://cis.org/vaughan/justice-department-agrees-end-subsidies-sanctuaries

47 Archived records relating to the various programs and amounts for 2015 can be found online at https://www.fema.gov/media-library-data/1438021101390-ce3bbdde8b84b174b8... and a list of the various Homeland Security grants that were available in FY 2016 can be found at https://www.fema.gov/fiscal-year-2016-homeland-security-grant-program.

48 The responsibility for oversight of foreign students and exchange visitors, as well as approval, denial, or withdrawal of approval (decertification) of schools and institutions of learning seeking permission to enroll them, is handled by the Student Exchange Visitor Program (SEVP) at Immigration and Customs Enforcement. For 18, grounder, Jan. 2015. https://cis.org/disabling-detainers Sanctuaries” Feb. 25, 2016. https://cis.org/vaughan/justice-department-agrees-end-subsidies-sanctuaries

49 The DHS Centers of Excellence homepage can be found at https://www.dhs.gov/science-and-technology/centers-excellence. Within that web page, one can then click on the tab labeled “Office of University Programs” for more information about the interconnection between DHS and institutions of higher learning. A glance at current and “emeritus” centers of excellence include universities that are already or contemplating becoming, sanctuaries.

50 Dan Cadman, “Hammering Sanctuaries with Lawsuits”, CIS blog, Jul. 24, 2015. https://cis.org/cadman/hammering-sanctuaries-with-lawsuits

51 Dan Cadman, “Rending the Fabric of Truth in the Steinle Case”, CIS blog, Jul. 9, 2015, https://cis.org/cadman/rending-fabric-truth-steinle-case

52 The statute can be found at 8 U.S.C. § 1324. https://www.law.cornell.edu/uscode/text/8/1324 For more information on its potential application, see W.D. Reasoner, “Looking to One’s Own Backyard”, CIS blog, Jan. 2, 2012. https://cis.org/reasoner/looking-to-ones-own-backyard

53 “A Pen and a Phone: 79 immigration actions the next president can take”. CIS backgrounder, April 2016. https://cis.org/A-Pen-and-a-Phone-79-immigration-actions-the-next-preside...