Introduction

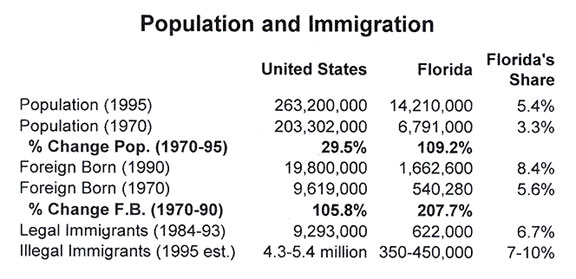

Florida is now the fourth largest state in the nation, with more than 14 million people in 1995. It is a fast-changing state, with a growth rate over the past 25 years of more than three times that of the entire nation. Many in business, politics or other pursuits are convinced that rapid growth is an asset, that "bigger is better," and that the state prospers by growing. Could they be wrong? Could rapid population growth be harmful? Could this growth involve costs — usually overlooked — and an undesirable impact on quality of life? This paper addresses these questions in the context of immigration and calls on Floridians to reassess the impact of growth upon the state.

Within the lifetime of a few old-timers, Florida' s population has surged from less than one million in 1920 to almost five million in 1960 to 9.7 million in 1980, and to 13 million a decade later. This growth of more than three million persons in the 1980s exceeded the total population of Florida in 1950 (see Figure 1).

Since Florida became a state 150 years ago, its population has grown on average 2½ times as fast as the entire United States. One result of rapid growth is a relatively high density of population. Florida's is more than 3½ times the national figure.

Rapid growth has transformed Florida's landscape from rural to urban in a few decades; by 1990, 85 percent of its people lived in urban areas. Swamps have become golf courses and shopping malls. Once-isolated beaches are now dominated by high-rise hotels and condominiums. Quiet country roads have been replaced by highways buzzing with traffic. Cities have arisen with both skyscrapers and slums, surrounded by burgeoning suburbs with their own schools, hospitals and shopping centers.

The components of population growth are fertility, mortality and migration. In Florida, natural increase (births minus deaths) constitutes a minor factor in growth. The relative shares of recent population growth allocate to natural increase only 13 percent of the state's growth, while migration (domestic and international) was responsible for 87 percent, or five-sixths of Florida's increase. The rate of increase in Florida's foreign-born population is twice that of the state’s very high overall rate of increase, demonstrating that immigration is leading that increase, second only to domestic migration from other states.

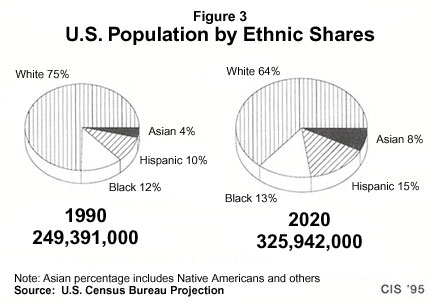

This report focuses on immigration and how it is contributing to change in Florida's population. As recently as 1940, only 4.1 percent of Floridians were foreign born compared to 8.8 percent for the nation. By 1990, more than one in eight (12.8%) of the state's residents were immigrants compared to less than one in twelve (7.9%) for the nation. We also explore what the prospects are for the future, if these current trends continue.

National Population Change and Immigration

Although immigration plays a major role in the growth of Florida, many aspects of it are beyond the policy purview of state authorities. The Mariel boatlift and the agreement with Cuba to admit a minimum of 20,000 Cubans each year are examples that come readily to mind. The same is true of overall population change. Whether it's fertility or migration, the federal role is far more determinant than that of the states. For that reason, we begin this report with a brief review of the current national demographic picture, a retrospective look back 25 years and then speculation on what the next 25 years hold in store.

The Present

The nation's population has now reached about 263 million, an increase of 14 million since the 1990 census. In that five-year period, about nine million people have been added through natural increase and another five million through net international migration. At current rates, net migration will be over 10 million during this decade. No records are kept on how many leave the country permanently nor on how many enter illegally. It is generally agreed, however, that between 160,000 and 250,000 people leave every year while hundreds of thousands enter the country clandestinely or fail to depart at the end of a temporary stay — for a net addition of at least 300,000. As a result, net immigration, whether legal or illegal, accounts for at least one-third of recent population growth.

The Recent Past (1970-1995)

Over the past quarter of a century the U .S. population has increased at a faster pace than that of any other industrialized nation. The 1970 U.S. census enumerated 203 million people. That number had surpassed 249 million by 1990; by 1995, 60 million people had been added to the nation's population in just 25 years. This represents an annual average rate of growth of over 1.1 percent per year. If that rate is maintained, the population will double in less than 65 years.

What was the impact of immigration? According to a recent study prepared by the Urban Institute, if immigration had come to an end in 1970, the 1990 population of the United States would have been 229 million rather than 249 million. Thus, immigration, directly and indirectly, accounted for 44 percent of all growth over those two decades. A recent estimate by the Center for Immigration Studies puts the share of population growth due to immigrants and their U.S.-born children at over 50 percent.

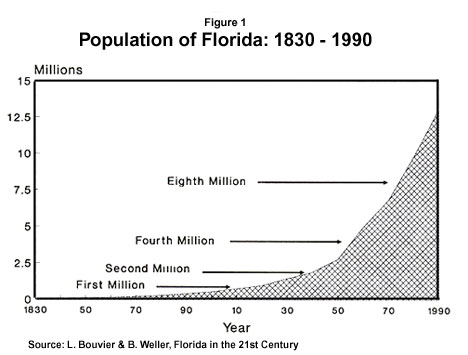

Immigration has increased in recent years. New immigrants -not counting illegal entrants — totaled 4.5 million in the 1970s; in the 1980s, they rose to 7.3 million; and at current rates, they will exceed nine million this decade (see Figure 2). The pattern of immigration can be seen when examining the numbers and regional origin of immigrants arriving over the past four decades. Because of this escalating immigration, the foreign-born population in the United States reached 24 million in 1995, fully 9.2 percent of the population, and it likely will exceed ten percent at the turn of the century.

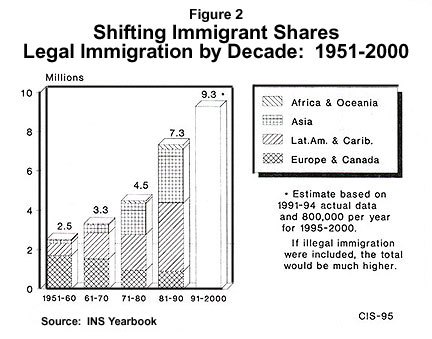

Because the origin of recent immigrants is very different from the ethnic background of our country, immigration is the major cause of rapid change in the diversity of the nation. In 1970, non-Hispanic Whites (hereinafter simply Whites) comprised 85 percent of the nation's population. Now, that share is below 75 percent. The Black proportion has remained fairly stable, rising from 10 to 12 percent during these two decades. In contrast, the Hispanic share has doubled from 5 to 10 percent and Asians have seen their share grow from less than one percent in 1970 to close to four percent today.

The Near-Term Future (1995-2020)

According to the Census Bureau's medium projection, the population will teach 275 million in 2000, rise to 298 million in 2010, and approximate 323 million in 2020. If both fertility and immigration remain at current levels, some 70 percent of the growth between 1995 and 2020 will be attributable to immigration, whether directly by the newcomers or indirectly by their U.S.-born offspring.

The Census Bureau now projects a U.S. population, based on current trends, of about 400 million by the middle of the next century, 50 percent more numerous than today. Whether this projection becomes reality will depend on actions we take today to shape our future.

Current immigration levels will continue to produce rapid change in the nation's ethnic composition. The Census Bureau projects that, by 2020, Whites will represent 63.9 percent of the population; Blacks 13.3 percent; Hispanics 15.2 percent; and Asians 7.6 percent (see Figure 3). If the trends in fertility and immigration continue to mid-century, by 2050, no single ethnic group will constitute a majority of the populace.

Can the United States accommodate this change, given the current problems of its cities, the shortages of water, the accumulation of wastes, the persistent poverty and recurring cycles of unemployment? Over the past 25 years, the nation has added 60 million people. Can it realistically accommodate another 60 million over the next 25 years plus another 75 million in the following 30 years? A growing number of Americans — scientists, environmentalists and others — consider the United States already to be overpopulated.

Of course, decisions taken today by individuals and by government at all levels will shape the future. Fertility might decline from its present average rate of 2.0 births per woman to 1.7 by 2000 and then gradually to 1.6 by 2020, but this would not in it itself stop the population surge. The change in fertility plus reduced immigration — to about 200,000 annually — would still result in a population of almost 300 million by 2020. This would be a large increase to accommodate, but some 25 million fewer than if current trends continue. Beyond that date — after 2020 — a leveling in population size would begin to take hold.

These are issues affecting every American and every immigrant to our shores. Many are already feeling the pinch. And in the states most affected by immigration, like Florida, steps are already underway to attempt to influence the future course of events without waiting for Washington to act.

Florida's Population Boom

Florida's growth can best be termed a "population boom." The Census Bureau estimates the July 1, 1995 population at 14,210,000. Given the usual undercount, it is perhaps safe to say that by now there are close to 15 million Floridians, not counting "snow birds" (northerners who spend their winters in the South) and other long-term vacationers. The state has added 1.2 million people over the past five years, more than any other state except California and Texas, and at a higher rate of increase than those two larger states.

Each year from 1990 to 1995, Florida gained about 70,000 people through legal immigration, a flow which represents about 30 percent of the state's annual growth. The Immigration and Naturalization Service estimates that in 1992 about 322,000 illegal immigrants — 11 percent of the national total at that time — resided in the state. With continued large-scale illegal immigration, Florida' s resident illegal population today could be as high as 450,000.

Demographically, Florida is distinct. Because of the influx of retirees, its average age is much higher than elsewhere, and its births barely exceed deaths. Migration from other states continues to be the prime contributor to population growth, but international migration plays an important role, particularly in the southern parts of the state. Florida has, by far, the largest net domestic migration in the nation and ranks third in international movements.

Current Conditions

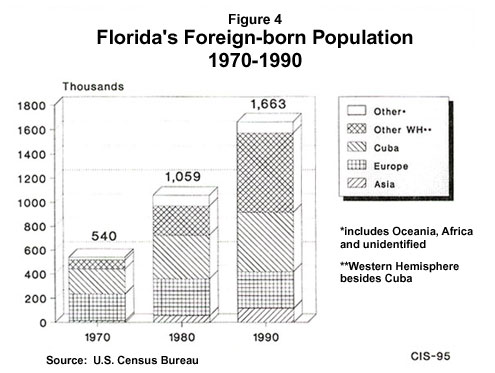

Almost 1.7 million foreign-born people lived in Florida in 1990 representing 12.8 percent of the state's population (see Figure 4). That is more than half again the national 7.9 percent foreign- born rate in 1990. The Florida total has since increased to perhaps two million. About 40 percent of the foreign born arrived since 1980. As shown in Table 2, in 1990 nearly 30 percent had come from Cuba (497,610). Other leading sources included Haiti (83,249), Canada (77,559), Jamaica (74,863), Nicaragua (72,060), Colombia (66,614) and the United Kingdom (61,069).

Only 43 percent of Florida's immigrants have become U.S. citizens. The proportions vary from 80.4 percent for those born in Italy and 76.2 percent for those from Germany to six percent for Nicaraguans and 19.3 percent for those from Haiti. The naturalization rate for the Cuban born is 47.2 percent.

With the growing foreign-born population, it is not surprising that of all Floridians age five and over, more than one in six (17.4%) do not speak English at home. And of those, 45.8 percent admit that they either speak no English or speak it poorly. In Dade County, well over half (57.4%) do not speak English at home, and most of those (54.6%) either do not speak English at all or speak it poorly. These proportions and numbers will have increased since the 1990 census with the continued surge in immigration, legal and illegal.

The 1990 census identified 5,134,869 households in Florida, of which 69 percent were family households. Four out of five (80.4%) of these were married couple households with or without children. The married couple proportion is greater among Whites and Asians (85.6% and 75.8%) than among Hispanics and Blacks (75.6% and 50.5%). Family size averaged 2.95 persons. It was lower among Whites (2.79) and higher among all other groups.

Recent immigrants have come primarily from Latin American and Caribbean sources. As a result, the Hispanic population more than trebled (from 451,382 in 1970 to 1,574,143 in 1990). From 15,006 in 1970 the Asian population has grown more than twelve-fold to 187,000 in 1990. Together with the Native Americans, they comprise 1.4 percent of the state’s population. While Cubans hold the largest share of the Hispanic population (slightly more than half), no single group predominates among Asians. Koreans, Vietnamese, Indians, Filipinos, Chinese and Japanese are all represented.

As a result of this growing level of immigration, the majority White share of the state’s population dropped from 84.3 percent in 1970 to 76.7 in 1980 and to 73.2 in 1990. It is possibly below 70 percent today. Similarly, the Black share of the population also fell -from 15.3 percent in 1970 to about 13 percent in 1990 - while their number over the years was increasing - going from just over one million in 1970 to 1.7 million in 1990. This is due to the continued in-migration of Whites from other parts of the country, as well as the wave of immigrants.

Median family income was $32,212 in 1990, while per capita income was $14,390. Income variations by ethnicity were substantial. While White families had median family incomes of $34,928, Blacks earned $20,334 and Hispanics $26,907. The family income of Asians was $33,821. About nine percent of Florida families had incomes below the poverty level ($13,359 for a family of four). The respective shares of incomes under the poverty level were: Whites-5.9 percent; Blacks-27.9 percent; Hispanics-15.6 percent; Asians-12.4 percent.

Health-related data for Florida present a mixed picture. The state's infant mortality rate is 7.4 per 100,000 for Whites and 16.6 for Blacks. This is slightly better than the national averages: 7.6 and 18.0, respectively. However, in 1993, there were 79.9 new AIDS cases per 100,000 population in Florida — double the national rate. Only New York had a higher rate. In Florida, there are fewer physicians per 100,000 population than nationwide (202 compared to 216), but there are more hospital beds per 100,000 than nationally (381 compared to 366).

The Recent Past (1970-1990)

Immigration to Florida is a recent phenomenon. As the Orlando Sentinel noted in an August 27, 1995 article: "Sparsely populated and with no industrial base, Florida was by-passed by the immigrants who flooded northern cities during the 19th and early 20th centuries. Only four percent of Florida residents in 1880 were foreign born. Tampa and Miami, combined, had only three Cuban-born residents that year."

But immigration has become a major contributor to population growth in Florida in recent years. Between the 1980 and 1990 censuses, Florida had the nation' s eighth fastest rate of increase in its foreign-born population — 57 percent. Between 1985 and 1990 alone, some 350,000 entered the state legally. Because of these growing movements of people from overseas to Florida, the foreign-born population of the state has grown from 540,284 in 1970 to perhaps two million today.

The source of this immigration has also shifted somewhat. In 1970, the Cuban-born population numbered 206,347. Just over 15,000 were foreign-born Asians. Together, Italy and Germany had 56,646 immigrants living in Florida. Other leading countries of origin included Canada (43,816) and the United Kingdom (40,192). Only 3,068 came from Mexico.

The 1980s provided the big push in immigration. In 1980, there were slightly over one million foreign born living in Florida. The number of European-born residents hardly changed over the 1980-1990 decade. The German-born population (35,023 in 1970) grew from 53,376 in 1980 to 55,321 in 1990. But the Asian and Hispanic-born populations soared. In 1980, Florida had 7,139 persons born in the Dominican Republic; by 1990, they numbered 23,373. The numbers from Vietnam doubled — from 6,347 to 12,843. Asian Indians more than tripled their numbers to 12,221. Colombians rose from 23,577 to 66,614 — all in but ten years.

The changes in both the size and sources of immigration to Florida are dramatic. While the share of the total population that is foreign born only rose from 10.8 to 12.8 percent between 1980 and 1990, the number increased by more than 600,000.

Regional Impact

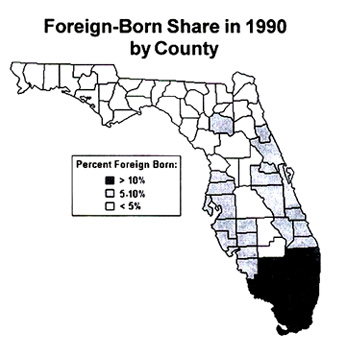

Various parts of a state may be affected differently by immigration, and this is particularly true of Florida. Miami (and the surrounding counties of Dade and Broward) represents the main magnet for immigrants, but with the growing tide of immigration the foreign-born have spread outward. For example, Hispanics make up 15 percent of Tampa's population and 14.2 percent of that of West Palm Beach. Central Florida rural counties have large Hispanic populations (Hardee 23.4%; Henry 22.3%; Collier 13.6%). But Florida's northern parts tell a different story .In Jacksonville, Hispanics form only 2.6 percent of the population and in Pensacola 1.6 percent.

Osceola county, near Orlando, had the largest percentage increase of Hispanics of any county in the nation during the 1980s. By 1990, 12 percent of its population was Hispanic. Once a small, rural county, Disney World opened just fifteen miles from Kissimmee, the county seat. Changes followed. According to an August 16, 1993 article in the Los Angeles Times, "Now, more changes are taking place…and the accent is Spanish." Between 1980 and 1990, the Hispanic population of the county rose from 1,089 to 12,866. It is now well over 15,000.

Conflict with long-time residents has occurred from time to time. One new Latino resident was cited in the same Los Angeles Times article as commenting: "Many people resent the fact that we're here. They think we've come too fast. I've been asked: Why did you come over here? My answer: 'Why not?'"

Miami

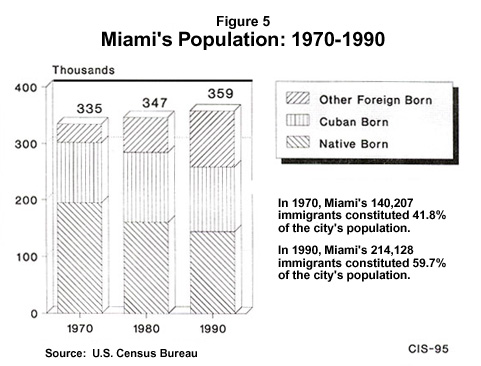

Miami, however, continues to represent the main center for immigration in Florida. In 1992, its estimated population was 367,016 and it is the 44th largest city in the nation. But since 1970, little growth has occurred in the city itself. Its population then was 334,859; by 1980, it had reached 346,681. Over the same period, however, the Miami metropolitan area grew very rapidly — from 1.2 million in 1970 to more than 2 million today. If the Ft. Lauderdale metropolitan area is included, the population has expanded from 1.9 million in 1970 to over 3.2 million.

Even in 1970, the city of Miami had a large foreign-born population (see Figure 5). It was one of the first cities in the nation to become a "minority-majority." In 1970, 44.6 percent of Miami’s population was Hispanic, 41.7 percent was White, 13.1 percent was Black and 0.6 percent was Asian or other. Already in 1970, 41.8 percent of Miamians were foreign born. The original exodus from Cuba began in the early 1960s. Thus, by 1970, large numbers of Cubans were already living in Miami — a total of 107,445 or about three-quarters of all the foreign born in Miami at that time.

Miami's ethnic composition was transformed in the 1970-1990 period. Coinciding with the rapid influx of immigrants, the White exodus began. From 139,798 Whites in 1970, the number had dwindled to 67, 799 by 1980. By then, Whites comprised but 19.5 percent of the population. Six out of ten Miamians were Hispanic -both native and foreign born — and still predominantly Cuban. Their numbers had climbed from 107,445 in 1970 to 149,305 in 1980. The Black population almost doubled between 1970 and 1980 and made up 23.6 percent of Miami's 1980 population. Less than one percent of the population was Asian or other. By 1990, the Hispanic share, now numbering 194,185, was up to 62.4 percent while Whites, at 44,091, made up but 12.3 percent. The Black ;hare remained quite constant at 24.7 percent and Asians and others remained at 0.6 percent of the population.

The sources of immigration to Miami have shifted somewhat since 1970, though they have remained mainly Hispanic. As noted, in 1970, of the 149,305 foreign-born residents, 75 percent were Cuban born. By 1990, Cubans barely made up the majority of the foreign-born population, then numbering 214,128, or more than 60 percent of the city's population.

During the 1980s and into the 1990s, large numbers of newcomers came from Nicaragua, Colombia, Peru and the Dominican Republic. Blacks came from Jamaica and Haiti. By 1990, 26,321 Nicaraguans and 18,035 Haitians were counted in the census. This compares to 158 and 486, respectively, in 1970. On the other hand, the European-born population of Miami fell from 15,286 in 1970 to 5,956 in 1990. The Asian-born rose from 1,525 to 2,013.

Unlike the situation in many metropolitan areas, greater Miami also has a large Hispanic population. Hialeah is 87 percent Hispanic and over half of Dade County's population is Hispanic. Middle and upper class Cubans, among others, have settled in the suburbs.

Of all of America's cities, only seven were revealed by the 1990 census to have more immigrants than native born. Miami is the largest city among this small number, and its foreign-born share (59.7%) is second only to Hialeah (70.4%). It is not that Miami has become more diverse; rather it has become increasingly a city of immigrants from Latin America. And the socioeconomic results have not been an unalloyed blessing.

Dade County schools are significantly over-crowded — in Florida, school districts are coterminous with counties — primarily because of continued immigration from Latin America. For example, Ben Sheppard Elementary in Hialeah may well be the largest such school in the nation, with almost 3,000 students. Only 12.8 percent of Miami adults have completed college, compared to the national average of 20.3 percent. Half of all Miamians age five and over admit to either not speaking English at all or speaking it poorly; and 73 percent speak a language other than English at home. However, three out of five foreign-born Miamians are naturalized, suggesting that many of the early arrivers from Cuba have taken up U.S. citizenship.

Miami has long had one of the highest crime rates in the nation. In 1991, there were 18,394 serious crimes per 100,000 compared to 5,928 for the nation.

Today, Miami stands out as an exception to most cities in Florida and in the nation. Yet, it may be a harbinger of things to come should immigration to the United States remain at its present high level. Within Florida, other areas also are rapidly being transformed.

Counties

We previously noted the distinction of Osceola County having the nation’s fastest rate of growth of its Hispanic population.

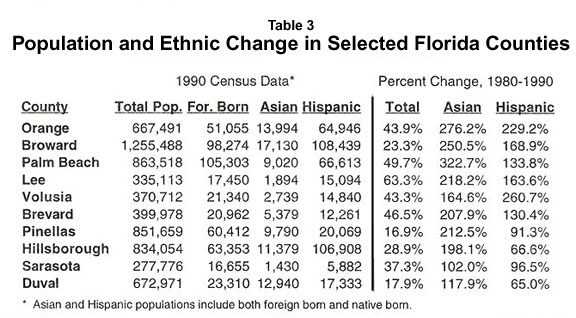

Other much larger counties that began with larger ethnic minority shares have also experienced large increases over the 1980-90 decade, albeit less dramatic in percentage terms. Dade County, the state's largest, increased 19.2 percent in overall population over this decade, while the share of the Hispanic population increased by 64.1 percent and the Asian population grew by 115.8 percent. The increase in these two ethnic groups was greater than the total population increase, representing an extreme case of demographic change. This means that at the same time as these minorities were increasing, Whites and/or Blacks were declining in number. Although some of this increase may be due to natural increase and internal migration, it seems likely that a major portion of it reflects the impact of international migration.

Table 3 above reflects similar data for other large counties, all of which have experienced greater levels of change than Dade County. Using Orange County (Orlando) as an example, the county’s population increased by about 44 percent between 1980 and 1990. Meanwhile, the Asian population increased by 276 percent and the Hispanic population by 229 percent. The data also show that the Asian and Hispanic populations together are larger than the 1990 foreign-born population, meaning that many of them are native-born Americans. The increase in Asian and Hispanic populations in Broward, Hillsborough and Orange counties represented over a quarter of the overall population increase.

The Next 25 Years (1995-2020)

Projections of current trends indicate that Florida’s population will surpass 15.3 million by the end of the century .The state’s Bureau of Economic and Business Research projects a population in 2020 of 20,158,000. In 2015, Florida is expected to pass New York to become the third largest state in the nation. It is estimated that four million persons will be added to Florida’s population between 1990 and 2020 through domestic migration. Only California and Texas will outstrip Florida in overall growth.

It is possible that the Census Bureau and the state have underestimated Florida’s growth. If Florida simply continued to increase by over 30 percent per decade — as it has since 1920 — the population in 2020 would be over 27 million. The Census Bureau assumes decreasing fertility and a constant level of immigration of just under 65,000 individuals annually, not including illegal entries. However, since 1985, legal immigration to Florida has approached 70,000 per year, again not including illegal entries. In addition, the agreement with Cuba to increase immigration to a minimum of 20,000 per year will be a significant boost to immigrant settlement in Florida. Further, case studies have shown that once an ethnic base of immigrants has been established, it builds on itself like a coral reef, as more immigrants, often from the same province of a foreign country, have come to join friends and relatives. Finally, immigrant women tend to have higher fertility than the native born, thus raising the overall fertility rate in the process.

Domestic in-migration is expected to continue at the rate of 150,000 per year as people continue to retire to Florida or come to the state to find employment. Yet this number could increase beyond expectations as the aging of the rest of the nation continues. Taking these factors into consideration, we believe that Florida’s population could surpass 22 million in 2020. If this proves correct, the state will have gained eight million inhabitants since 1995, a growth of 57 percent in just 25 years.

Impact of Population Growth

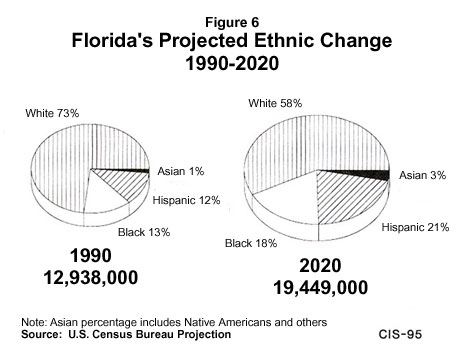

The demographic dice well may be cast. Without declines in fertility and migration (domestic and international), Florida will grow rapidly through this century and the next according to Census Bureau Projections. Florida's ethnic composition will change gradually with the share of Whites continuing to fall from 73.2 percent in 1990 to about 58 percent in 2020 (see Figure 6). Hispanics will likely increase from 12.1 percent in 1990 to nearly 21 percent in 2020. Asians will increase their share from 1.4 to three percent. The Black share will continue to increase slowly, aided in part by possibly growing numbers of immigrants from the Caribbean. From 13.2 percent in 1990, the Black proportion of the state's population likely will reach nearly 18 percent in 2020.

Will Florida in 2020 be on its way to being a heterogeneous, multi-racial society where no single group will predominate numerically, or will portions of the state become enclaves heavily shaped by foreign settlement, as Miami has become, while other areas continue to be less attractive to the influx from abroad? While changes in ethnicity have produced serious social problems in Florida, as well as in other states, perhaps Florida can profit from these experiences and avoid further inter-ethnic tensions.

The Aging of the Population

Florida has the largest population share (19%) of senior citizens (65 and older) in the nation. This elderly share compares with an estimated 12.8 percent for the nation in 1995. The fastest growing segment of the elderly are those age 85 and over. The rising number of elderly calls for more health professionals and technicians, for more clinics and hospitals, indeed a growth in every aspect of the health care establishment. Senior citizens also use libraries and take courses in schools and universities. Will Florida be ready to increasingly provide for the needs of the elderly in its educational and health care systems? Not unless expansion takes place in these areas.

Florida's elderly population is projected to more than treble over the next 30-year period. Looking beyond 2020, and due to the baby boomers becoming seniors, Florida can expect even more rapid growth among its elderly. By 2050, the elderly could number seven million, according to current trends. With growth amounting to 180,000 in this decade alone, now is the time for the state to begin making serious plans for the health and welfare of this rapidly growing segment of its population.

Education

Over 2.3 million children under 18 attended public school in Florida in 1994. School enrollment (pre-K through grade 12) will grow rapidly in future years. By 2000, over 2.8 million children will be attending the public schools of Florida. That number will increase to over three million by 2020.

Following trends in the general population, the ethnic composition of the school population will change. Between 1993 and 2020, the White proportion will fall from 61.1 percent to 54 percent; Hispanics will rise from 12.9 percent to 18 percent; Blacks will remain more or less steady at 24 percent; and Asians and others will move from 1.8 percent to four percent. The proportion of Hispanics and Blacks will be even greater in Dade County.

This forecast means that the state school system can expect to add as many as 750,000 pupils between 1995 and 2020. At current standards for building, the state would have to build a new school every five days for the next 25 years. Even assuming per capita expenditures of $3,000 per student, an additional $150 million will have to be allocated for the state's school system every year .In the recent state government report, "The Unfair Burden," it was estimated that educating limited English proficiency students cost the state over $518 million in 1993. As the tide of immigrants swells, that amount will grow. Florida must be prepared to spend more, not less, to educate its children for the challenges of the twenty-first century. Indeed, the growing complexity of technology, the need for retraining, and the increasing gap between the earnings of college graduates and those with only high school diplomas, will likely bring more students to colleges and universities in the state, further increasing the state's bill for education.

Transportation

The problems facing Florida's transportation infrastructure are immense and growing. Freeways, bridges, railroad tracks and mass transit are all deteriorating more rapidly than they are being replaced. In recent decades traffic has grown much faster than highway capacity.

Florida has 5.4 percent of the nation's population but just 2.8 percent of the road mileage. On average, Florida's roads have twice the traffic of typical roads in the United States, because Florida has half the lane-miles of roads per capita as the national average. What about the future, as the state's population (and the number of cars) keeps increasing?

The number of lane-miles in Florida increased by 14.8 percent during the 1980s. Yet the population increased by 32 percent. Maintaining 1990 per capita levels would require adding 168,000 lane-miles to the existing system by the year 2020. Given the resources currently at the disposal of the Florida Department of Transportation, such a development is unlikely. Further, many cities, e.g., Tampa, recognize that additional road building in the metropolitan area is prohibitive in cost and that t a mass transit system of railroads, subways and — trolleys is needed. But such improvements in efficiency and reduction of pollution are currently beyond the financial resources of state and local government. Nor is the federal government as likely to provide assistance to localities as it has in the past. The bottom line appears to be that the transportation structure of Florida can barely be maintained, let alone improved.

Crime

Many Floridians are demanding reform of the criminal justice system -including longer prison terms and serving out the sentences imposed, especially for dangerous criminals. Currently there are about 350 prisoners per 100,000 population. That rate has been rising every year at least since 1987 when it was 265. Even if it ceases to rise, by 2000 the number of people in Florida's jails will approach 55,000. At that fate of growth, the prison population in 2020 could be as high as 95,000. This would require a tremendous increase in funds for building prisons and hiring the prison personnel needed.

"The Unfair Burden" reported that in 1993 the state spent about $44 million on immigrant-related criminal justice. "Since 1988, Florida has assumed over $52 million in unreimbursed costs [for Mariel Cuban incarcerations]." This figure represents a sum nearly five times greater than expenditures made by the federal government and has contributed to Florida's over-crowded prisons. Without adequate prison space, as ordered by the Federal courts, Florida is forced to discharge many violent criminals before they have served 85 percent of their sentences, thereby contributing to the crime rate. This is an expensive cycle that has to be corrected. The $1.5 billion lawsuit filed in 1994 by Gov. Lawton Chiles sought to recoup these costs, among others, from Washington. Despite the doubt surrounding the future of the suit, the federal government has accepted the validity of the state's complaint.

Environment

The damage done to the environment by population growth is well-known. One of the state's (and nation's) premier parks provides an example: settlement, flood control and the draining of wetlands for agriculture have reduced by half the original Everglades system. In this area, disruption of natural water flows and pollution have dramatically reduced populations of wading birds and other species, damaged the Florida Keys' reef system and degraded fisheries in Florida Bay.

Elsewhere in the state, housing developments invade wetlands, which have declined from 51 percent of the state’s surface in 1900 to less than 30 percent today, and destroyed the natural habitat of some wildlife. The Florida panther and the manatee, among other species, are nearly extinct. The more humans expand into the habitats of other living things, the more biodiversity is reduced. Florida biologists calculate that, if the state is to save its birds, reptiles and mammals from extinction, an additional five million acres must be set aside to protect wildlife. But such a move is not in the cards at present. Instead, with the migrant-driven expansion of population, greater encroachment of developers into wetlands and farmland seems likely.

Water Resources

Florida is already in trouble with regard to water. Given the extent to which water is used for residential purposes — an average of 1,318 gallons per day per Floridian, and given the high share of land now going for residences, i.e., the state's population is 85 percent urban — migrant-driven population growth will severely impact water resources. More people mean a greater demand for water, urbanization paves over the land and reduces its absorption capabilities; and more people produce more pollution. In excess of 90 percent of the state’s water is drawn from underground, but Florida's sands and porous limestone are poor filters for the chemicals and toxins increasingly generated by humans. Water is becoming increasingly contaminated and shortages of water re more common.

In Southwest Florida, the watering of lawns is severely restricted, greater amounts of waste water are treated and recycled, and there is an ongoing dispute among Pinellas, Hillsborough and Pasco counties over water from wells. In South Florida the combination of dense coastal development and loss of interior wetlands has resulted in a rate of underground water pumping greater than the rate of recharge. This has caused water levels to drop, and the aquifer, acting as a sponge, has taken in ocean water and salinated the region’s fresh water supply.

Further population growth and urbanization can only accentuate the water problem. As the Orlando Lake Sentinel pointed out on July 16,1995, "At stake is destruction of the environment, including wetlands, private wells, lakes and estuaries that nourish one of the greatest fishing nurseries in the country." Some environmentalists and lawmakers have begun to call for a construction moratorium. The Sentinel quoted one environmentalist as saying, "We should really stop growing until we catch up with our resources." Water shortages are likely to become one of Florida’s most acute problems as it enters the 21st century.

Conclusion

It is said that demography is destiny. Past and present demographic behavior has produced 14 million Floridians. No doubt Florida is destined to continue to grow, to become more ethnically diverse, and to age even more.

The question is not whether Florida should or should not grow and change. The question before Floridians is the pace of change and how the state can best cope with increased growth, diversity, and aging. Florida's best course of action is to anticipate continued population increase, and while trying to reduce that increase, plan for it in such a way as to minimize any adverse effects on the persons already here. Florida’s citizens must consider the impact of future growth on resources and quality of life so that these may be passed on to the next generation with no diminution.

How can the pace of growth be slowed in Florida? There are only two real options — reducing fertility or reducing migration. While state government policies may be able to contribute to further reducing fertility and discourage migration from other states, it is foreign immigration which can be most directly shaped by government decisions.

Policies affecting legal and illegal immigration are established at the federal level. It is the federal government's responsibility both to limit legal immigration and keep out or remove illegal immigrants. Recent outcries against illegal immigration have compelled the" federal government to expand its Border Patrol and crack down on employers who knowingly hire illegals, but these efforts can be intensified. Florida sued the federal government for the money spent on caring for illegal immigrants and political refugees, mostly from Cuba, Haiti, and Honduras. In 1991 alone, it is estimated that these costs amounted to $195 million for education; $30 million for prisons; and $2.7 million for the state's share of Medicaid costs. The lawsuit was dismissed by a federal judge, but the state has vowed to pursue the case to the Supreme Court.

More important than recouping the expenses is the reminder to Washington that failed immigration policies have fiscal costs that the entire nation becomes accountable for. Perhaps because of this activism, and because of the new agreement with Cuba for an increased flow of Cuban immigrants, the administration announced in August 1995 the first award — of $18 million — would go to Florida under the new federal immigration emergency fund.

If Florida is to have any hope of achieving a sustainable population in the future, it must see to it that not only illegal immigration is halted but that legal immigration is reduced sharply by Federal action. At present over a million immigrants enter the United States each year, including new illegal residents, the highest number for any industrialized nation. Legislation has been introduced in Congress that would curtail legal immigration. If such legislation were passed, and illegal entry forestalled, immigration, and thus population growth, in Florida could be significantly reduced.

Floridians should recognize that growth comes at a cost. If Floridians ignore the issues of migration and lower fertility, and refuse to provide revenue for the public sector at a pace sufficient to keep up with population growth, then per capita services and the quality of life will deteriorate. Roads will be more congested, the justice system will be overburdened, health services will be inadequate and Florida's educational system — the investment in human resources that pays high dividends in future years — will go downhill. At some future point, Florida's population density and deteriorating infrastructure would make it an undesirable place to live. At some future point, Florida's wealth of natural resources and wildlife could be depleted beyond renewal.

Floridians — whether native-born or foreign-born — are rapidly letting the natural heritage they will leave to future generations be eroded by population growth. Now is the time to face up to the need to reverse the trend. It requires foresight, altruism, political courage and a crusading spirit; that is the challenge.

Dr. Leon Bouvier is a Senior Fellow at the Center for Immigration Studies and Adjunct Professor of Demography at the Tulane University School of Public Health. He is also a Visiting Scholar at Stetson University and served as a demographer to the U.S. Select Commission on Immigration and Refugee Policy in 1980.

William Leonard is Adjunct Professor of International Studies at the University of South Florida and President of Floridians for a Sustainable Population.

John Martin is the Director of Research at the Center for Immigration Studies in Washington, D.C. He is a former career Foreign Service Officer who specialized in policy formulation and political analysis.