pp. 15-17 in Immigration Review no. 22, Fall 1995

The public recently has received a dose of press accounts about a rush of immigrants applying to become U.S. citizens. This has been attributed to various influences, but most often to a fear — in the wake of the adoption of Proposition 187 in California — of discrimination against aliens. A similar influence identified in many news accounts is the "Contract With America" effort by the Republican majority in Congress to balance the federal budget in part by curtailing welfare programs for non-citizens, among others. The number of citizenship applications certainly is higher than at this time last year, yet a look at the trend suggests that the increase is part of a surge in applications that began in 1992 — well before Proposition 187 was proposed or reform of welfare eligibility gained momentum.

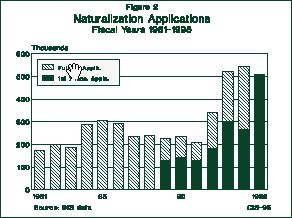

The reason for the upsurge in naturalization applications in large measure is simply the increase in the number of eligible immigrants. For the seven years before the 1986 IRCA legislation went into effect (1981-87) the average number of new legal immigrants recorded by the INS was about 581,000 per year. During the next seven years the average jumped by over 25 percent to 729,400 per year — not counting the illegal aliens who were granted legal residence under the IRCA amnesty provision. When they are included in the calculation, the average number of new immigrants over the most recent seven-year period increased by nearly 47 percent to about 853,000 per year.

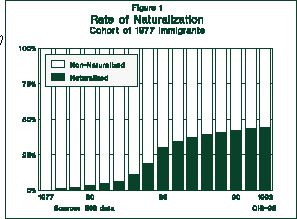

Citizenship eligibility normally requires five years of residence in the United States (spouses and children of U.S. citizens are eligible after three years, and special provisions allow even faster naturalization for children of government employees being sent abroad). Therefore, the first of this new wave of immigrants became eligible to apply for citizenship in 1992. However, the bulk of naturalizations historically have occurred in the seventh or eighth year after entry (see Figure 1 below).

Figure 1.

The speed of processing an application for citizenship — which includes a fee, a test of English comprehension for all but elderly long-time residents, and a civics test — varies among jurisdictions, but may take a year or more, and the wait has become longer with the increased number of applicants. During FY'94, about 450,000 applications were either approved or denied, but that was less than the 543,000 applications filed, so the waiting list grew longer.

Naturalization applications, which averaged 235,573 per year during the 1980s and were 206,688 in 1991, jumped to 342,269 in FY'92, and then by over 52 percent to 521,868 in FY'93. FY'94 maintained the high level of naturalization applications, but the level of further increase was a modest 4.1 percent to 543,353. This sharp upward trend beginning in FY'92 (see Figure 2 below) constitutes the trend for evaluating the FY'95 increase. Partial data for the first seven months of FY'95 — through April — put the number of applications at 508,521, over 90 percent higher than for the same seven months the previous year, but only two-thirds higher than in the same period in FY'93. These data show that interpretations ascribing the increase in naturalization applications to the welfare reform legislation and Proposition 187 may be misleading if they ignore the fast pace of increase that antedated those developments.

Figure 2.

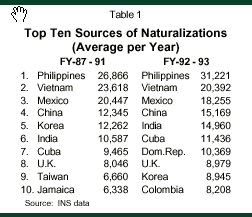

Looking at INS data on naturalizations ‹ which differ from application data because they exclude applications that are denied (about 9% in FY-94) and because processing lags behind applications — ten countries account for about two-fifths of all new citizens (see Table 1). However, a change occurred among the top ten between FY-87-91 and FY-92-93. In the most recent period, the Dominican Republic and Colombia replace Taiwan and Jamaica.

The comparison of the two periods reflects a significant drop in naturalizations by Koreans (down 27%) and an even greater decline among immigrants from the former Soviet Union (down 48%). However, the greater number of increases is explained by an overall eight percent rise in naturalizations in the FY-92-93 period. Among countries on the top ten list, naturalizations by persons from the Dominican Republic increased by nearly 80 percent, from Colombia by 65 percent, from India by 41 percent, from China by 23 percent, and from Cuba by 21 percent. Other nationalities that registered major increases in naturalizations included Canadians (up 59%), Haitians (up 32%), Pakistanis (up 31%) and Guyanese (up 27%).

Of particular note from this country-of-origin data is the fact that the number of Mexicans naturalizing registered a slight drop, rather than the increase that would have been expected if the change were due to the immigrants newly eligible to apply for citizenship as a result of the IRCA amnesty. This is not to say that the continued rapid increase in applications experienced this year is not fueled by the amnesty, but it was still too early for much of the legalized population to apply two or three years ago. This underscores the fact that the earlier increase, and probably much of the current trend, results from the general increase in immigration, rather than that specific program.

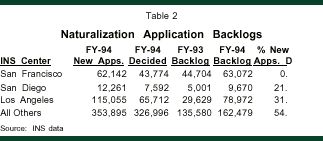

The largest numbers of citizenship applications have come from the states with the greatest concentration of new immigrants — California and Texas. In California, none of the three INS offices processing applications has been able to keep up with demand (see Table 2). In San Francisco, fewer applications were processed than were on the waiting list at the start of the year. Therefore, if the waiting list cases were processed first, no new applications were decided (although we assume there may have been a few expedited cases for dependents of U.S. government employees assigned overseas.) Even when the California data are separated from the national data, the INS offices were able to act on only slightly more than half of the new citizenship applications filed during FY-94.

Citizenship re-quires that the immigrant renounce allegiance to any other country of nationality, in exchange for which is gained the ability to fully participate in the governance of this country by voting in elections and becoming eligible for elective office. For this reason, many commentators have lamented the generally low percentage of immigrants who naturalize. The 1990 census found that about eight million (40%) of 19.8 million foreign-born residents included in the census (without regard to their legal status) were naturalized U.S. citizens. The other 11.8 million — including 2-2.5 million illegal immigrants and 3-3.5 million recent immigrants, who were ineligible to apply for naturalization — clearly included a very large number of immigrants eligible to apply for citizenship, but who had not done so. Some of these persons could be joining the more recent immigrants who are becoming newly eligible and applying for citizenship, but this remains to be seen.

The Mexican government is considering legislation to allow its citizens to retain Mexican nationality even though they renounce Mexican citizenship to become U.S. citizens. This may remove a disincentive to Mexican immigrants applying for U.S. citizenship. At present, under Mexican law, naturalization removes the right to own property in Mexico along the frontiers. Commentators have suggested that this explains much of the low rate of naturalization by Mexican immigrants (22.6% in 1990) and indicates that a still greater future surge in naturalization applications is possible. However, as noted above, the Mexican data may be distorted by a significant number of nationals in the 1990 census who were not eligible for U.S. citizenship because they are illegal residents, and others may be deterred from applying by a low level of academic achievement, which makes passing the civics and English tests more difficult.

"The INS could not have anticipated the surge which many current applicants have attributed to the policy debate over eliminating noncitizens' rights."

—INS Commissioner Doris Meissner

April 13, 1995 San Francisco Chronicle

The INS has recognized the challenge of the burgeoning naturalization application workload and the growing backlog. It has been authorized to hire more than 1,000 additional people to process the applications. It estimates that it will be able to increase processing capacity from 504,000 to 720,000 applications annually with the new personnel and some streamlined procedures — although it didn't actually handle 504,000 cases last year, and the number this year will be in excess of 720,000. INS Commissioner Meissner, who earlier announced plans to encourage naturalization by working with voluntary organizations, now has announced a $500,000 fund for a pilot project in California to facilitate naturalization applications. However, it makes little sense to devote resources to increasing naturalization applications at a time when there are already more than the INS can handle.

—John Martin