Download a PDF of this Backgrounder.

Steven A. Camarota is the director of research and Karen Zeigler is a demographer at the Center for Immigration Studies.

Data from the Census Bureau shows that 42.4 million immigrants (both legal and illegal) now live in the United States. This Backgrounder provides a detailed picture of immigrants, also referred to as the foreign-born, living in the United States by country of birth and state. It also examines the progress immigrants make over time. All figures are for both legal and illegal immigrants who responded to Census Bureau surveys.

Among the report's findings:

Population Size and Growth

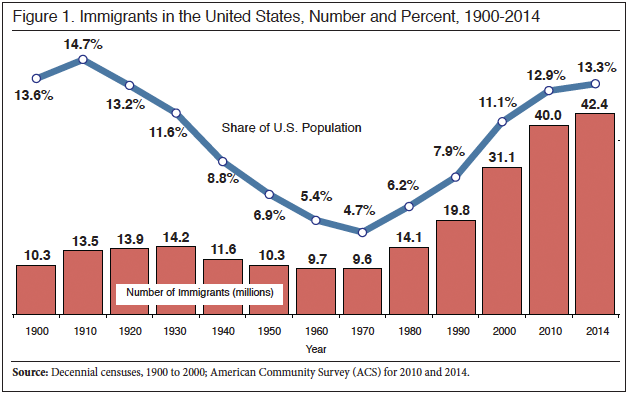

- The nation's 42.4 million immigrants (legal and illegal) in 2014 is the highest number ever in American history. The 13.3 percent of the nation's population comprised of immigrants in 2014 is the highest percentage in 94 years.

- Between 2000 and 2014, 18.7 million new immigrants (legal and illegal) settled in the United States. Despite the Great Recession beginning at the end of 2007, and the weak recovery that followed, 7.9 million new immigrants settled in the United States from the beginning of 2008 to mid-2014.

- From 2010 to 2014, new immigration (legal and illegal) plus births to immigrants added 8.3 million residents to the country, equal to 87 percent of total U.S. population growth.

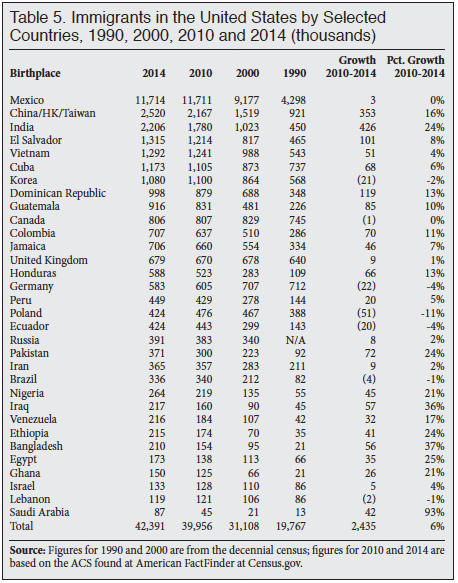

- The sending countries with the largest percentage increases in immigrants living in the United States from 2010 to 2014 were Saudi Arabia (up 93 percent), Bangladesh (up 37 percent), Iraq (up 36 percent), Egypt (up 25 percent), and Pakistan, India, and Ethiopia (each up 24 percent).

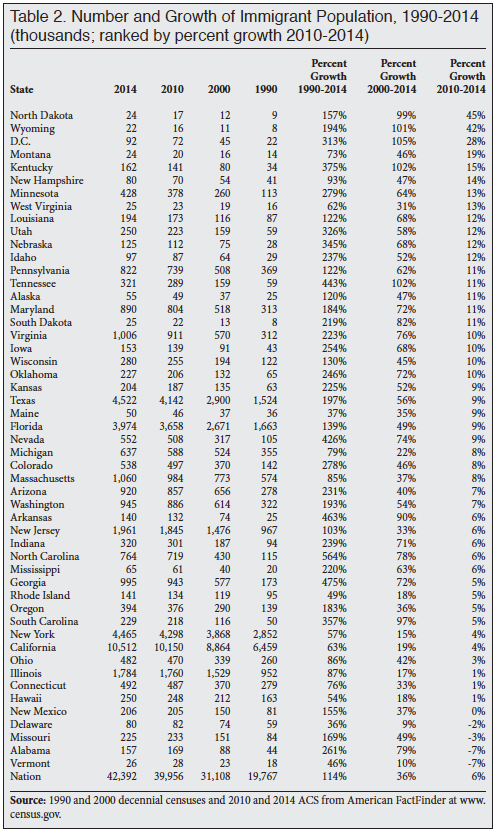

- States with the largest percentage increases in the number of immigrants from 2010 to 2014 were North Dakota (up 45 percent), Wyoming (up 42 percent), Montana (up 19 percent), Kentucky (up 15 percent), New Hampshire (up 14 percent), and Minnesota and West Virginia (both up 13 percent).

Labor and Employment

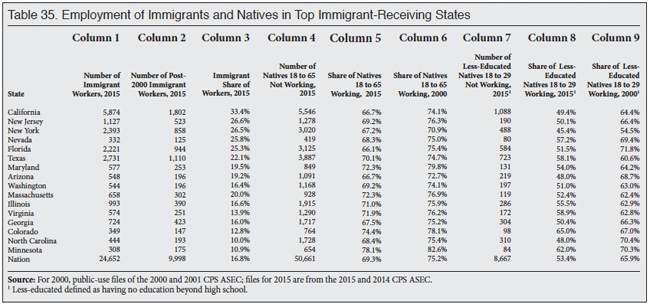

- Rates of work for immigrants and natives tend to be similar — 70 percent of both immigrants and natives (ages 18 to 65) held a job in March 2015.

- Immigrant men have higher rates of work than native-born men — 82 percent vs. 73 percent. However, immigrant women have lower rates of work than native-born women — 57 percent vs. 66 percent.

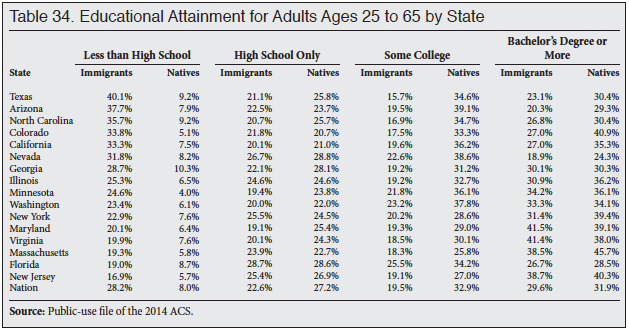

- A large share of immigrants have low levels of formal education. Of adult immigrants (ages 25 to 65), 28 percent have not completed high school, compared to 8 percent of natives. The share of immigrants (25 to 65) with at least a bachelor's degree is only slightly lower than natives — 30 percent vs. 32 percent.

- Because many immigrants have modest levels of education, they have significantly increased the share of some types of workers relative to others.

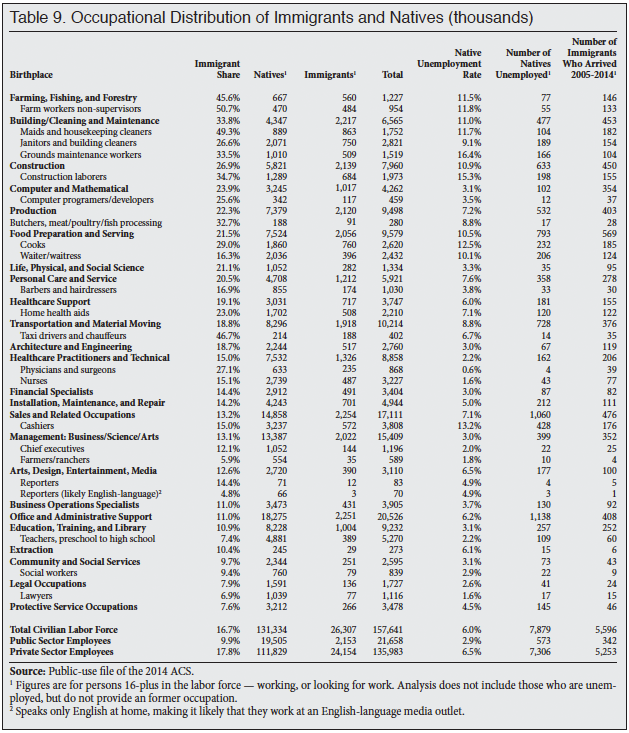

- In 2014, 49 percent of maids, 47 percent of taxi drivers and chauffeurs, 33 percent of butchers and meat processors, and 35 percent of construction laborers were foreign-born.

- While the above occupations are often thought of as overwhelmingly comprised of immigrants, most of the workers in these jobs are U.S.-born.

- Workers in other occupations face relatively little competition from immigrants. In 2014, 5 percent of English language journalists, 6 percent of farmers and ranchers, and 7 percent of lawyers were immigrants.

- At the same time immigration has added to the number of less-educated workers, the share of young less-educated natives holding a job declined significantly. In 2000, 66 percent of natives under age 30 with no education beyond high school were working; in 2015 it was 53 percent.

Socioeconomic Status

- Despite similar rates of work, because a larger share of adult immigrants arrive with little education, immigrants are significantly more likely to work low-wage jobs, live in poverty, lack health insurance, use welfare, and have lower rates of home ownership.

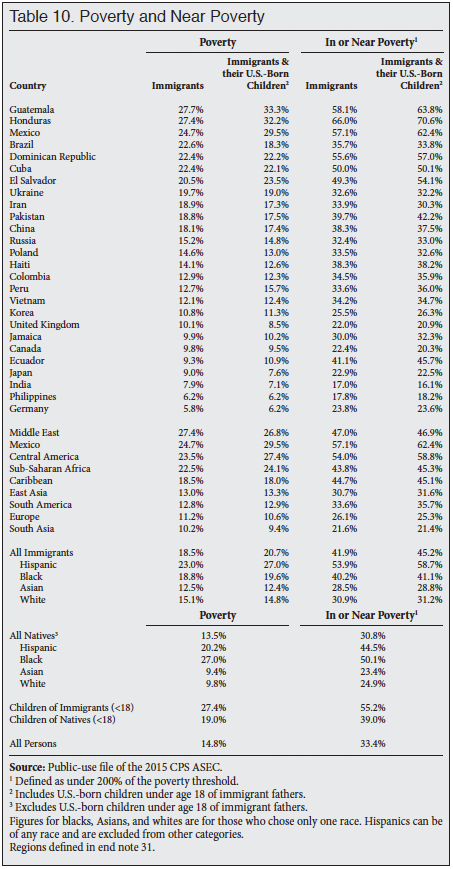

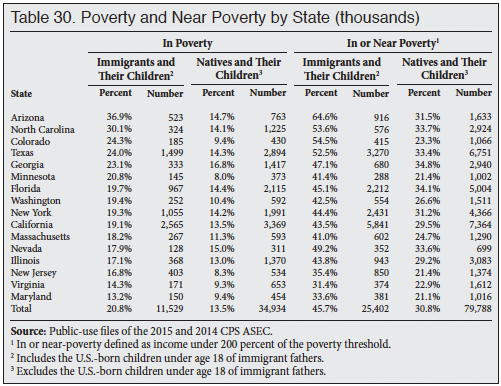

- In 2014, 21 percent of immigrants and their U.S.-born children (under 18) lived in poverty, compared to 13 percent of natives and their children. Immigrants and their children account for about one-fourth of all persons in poverty.

- Almost one in three children (under age 18) in poverty have immigrant fathers.

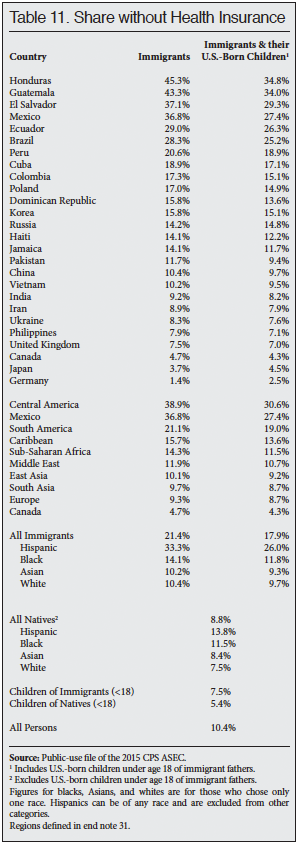

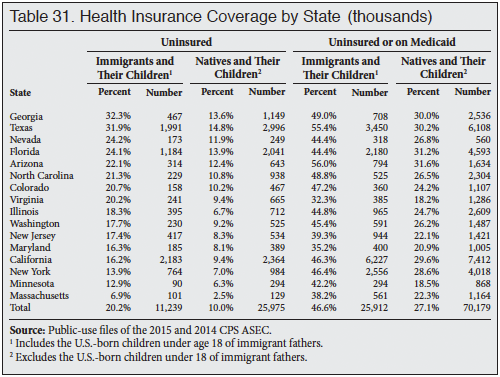

- In 2014, 18 percent of immigrants and their U.S.-born children (under 18) lacked health insurance, compared to 9 percent of natives and their children.

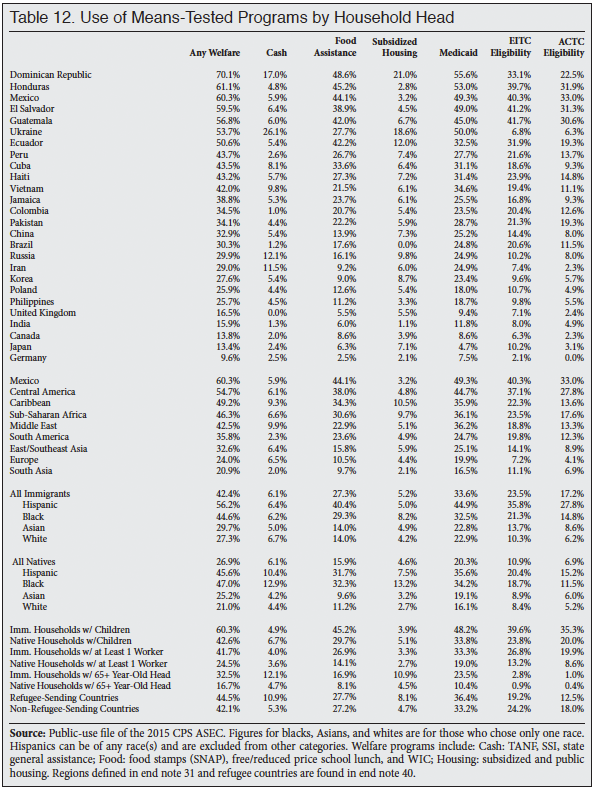

- In 2014, 42 percent of immigrant-headed households used at least one welfare program (primarily food assistance and Medicaid), compared to 27 percent for natives. Both figures represent an undercount. If adjusted for undercount based on other Census Bureau data, the rate would be 57 percent for immigrants and 34 percent for natives.

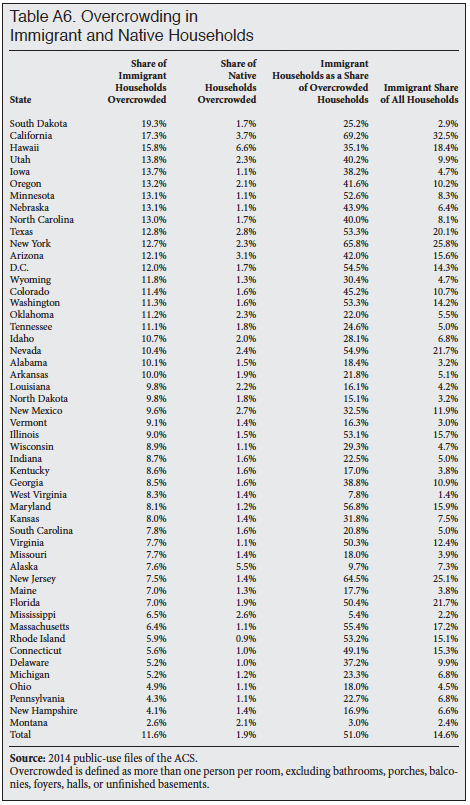

- In 2014, 12 percent of immigrant households were overcrowded, using a common definition of such households. This compares to 2 percent of native households.

- Of immigrant households, 51 percent are owner-occupied, compared to 65 percent of native households.

- The lower socio-economic status of immigrants is not due to their being mostly recent arrivals. The average immigrant in 2014 had lived in the United States for almost 21 years.

Immigrant Progress Over Time

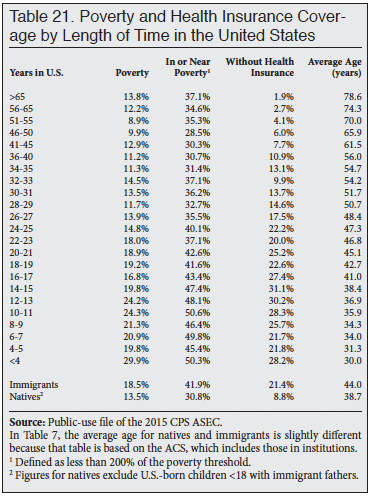

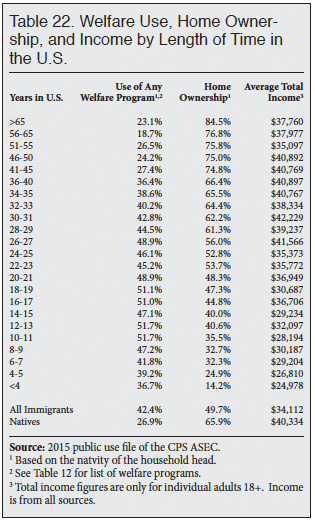

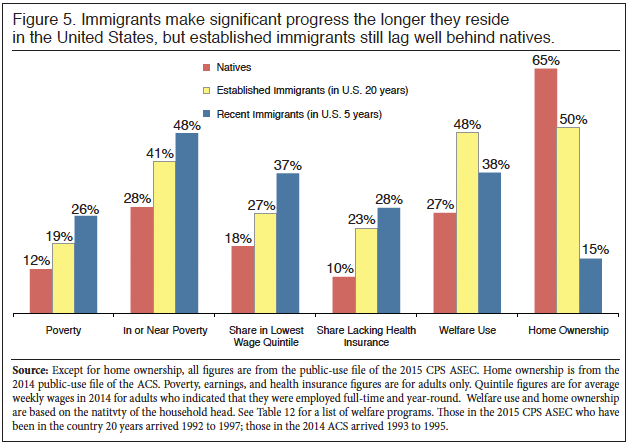

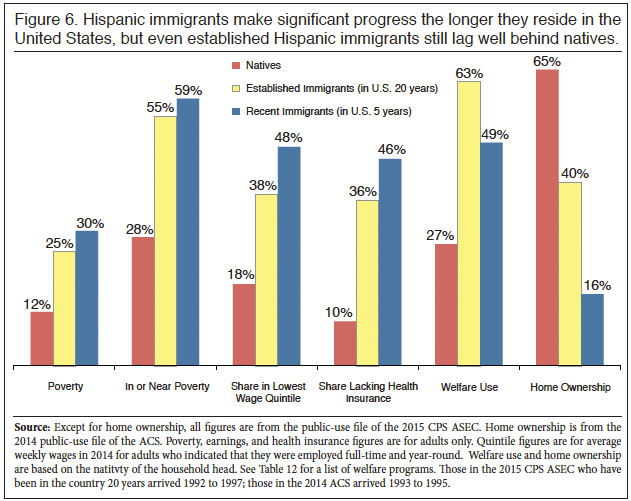

- Immigrants make significant progress the longer they live in the country. However, even immigrants who have lived in the United States for 20 years have not come close to closing the gap with natives.

- The poverty rate of adult immigrants who have lived in the United States for 20 years is 57 percent higher than for adult natives.

- The share of households headed by an immigrant who has lived in the United States for 20 years using at least one welfare program is 80 percent higher than native households.

- The share of households headed by an immigrant who has lived in the United States for 20 years that are owner occupied is 24 percent lower than that of native households.

Impact on Public Schools

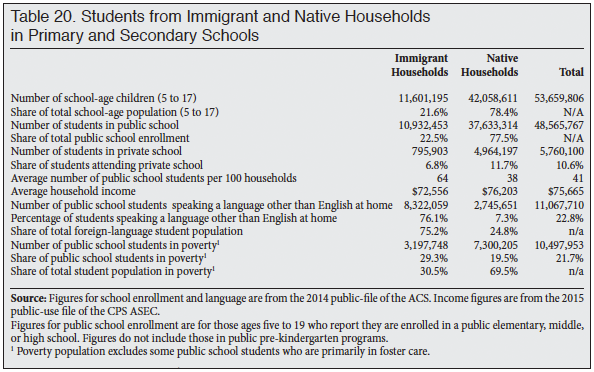

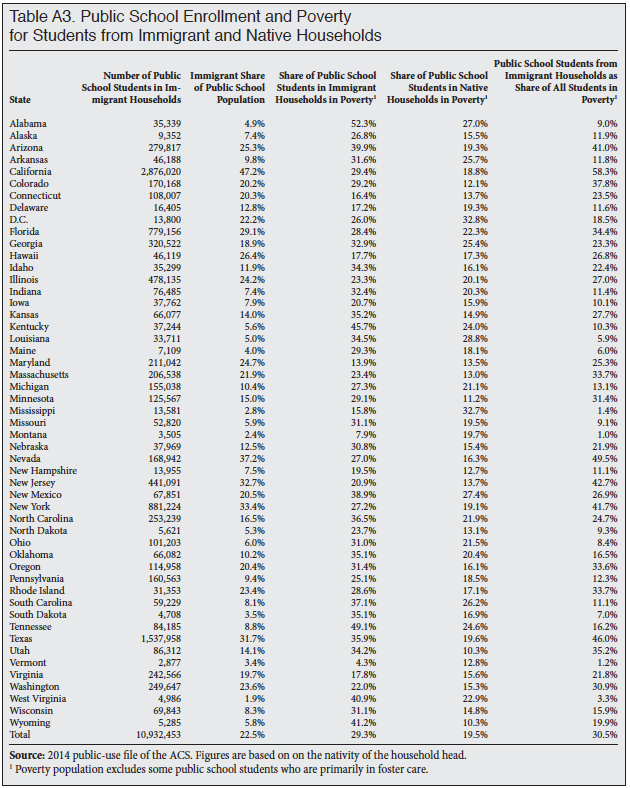

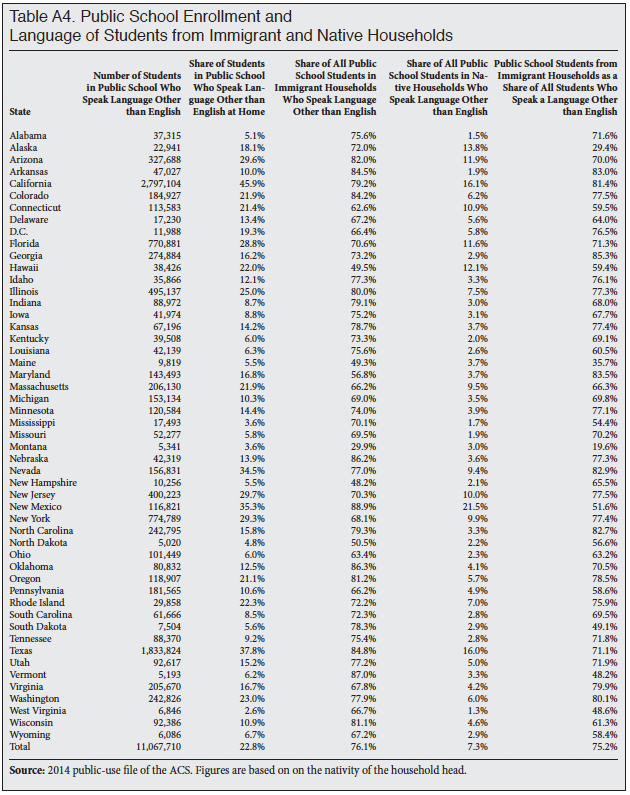

- There are 10.9 million students from immigrant households in public schools, and they account for nearly 23 percent of all public school students.

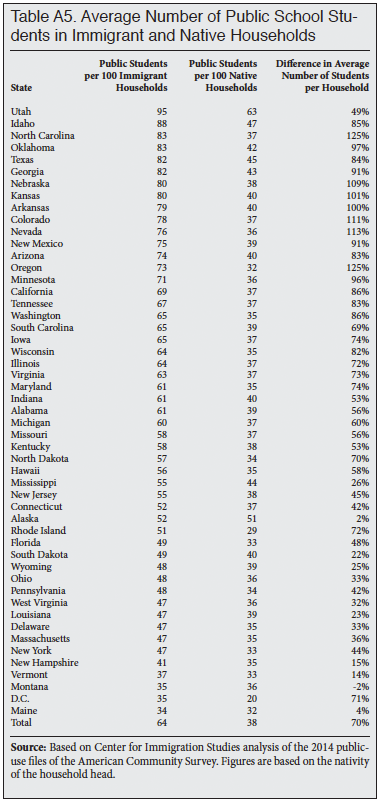

- There are 64 public school students per 100 immigrant households, compared to 38 for native households. Because immigrant households tend to be poorer, immigration often increases school enrollment without a corresponding increase in the local tax base.

- In addition to increasing enrollment, immigration often creates significant challenges for schools by adding to the number of students with special needs. In 2014, 75 percent of students who spoke a language other than English were from immigrant households, as are 31 percent of all public school students in poverty.

- States with the largest share of public school students from immigrant households are California (47 percent), Nevada (37 percent), New York and New Jersey (33 percent each), and Texas (32 percent).

Entrepreneurship

- Immigrants and natives have very similar rates of entrepreneurship — 12.4 percent of immigrants are self-employed either full- or part-time, as are 12.8 percent of natives.

- Most of the businesses operated by immigrants and natives tend to be small. In 2015, only 16 percent of immigrant-owned businesses had more than 10 employees, as did 19 percent of native-owned businesses.

Impact on the Aging of American Society

- Recent immigration has had a small impact on the nation's age structure. If post-2000 immigrants are excluded from the data, the median age in the United States would still be 37.

- Recent immigration has had a small impact on the nation's fertility rate. In 2014, the nation's total fertility rate (TFR) was 1.85 children per women. Excluding all immigrants, it would have been the rate for natives — 1.78 children per woman. The presence of immigrants has increased the nation's TFR by about 4 percent.

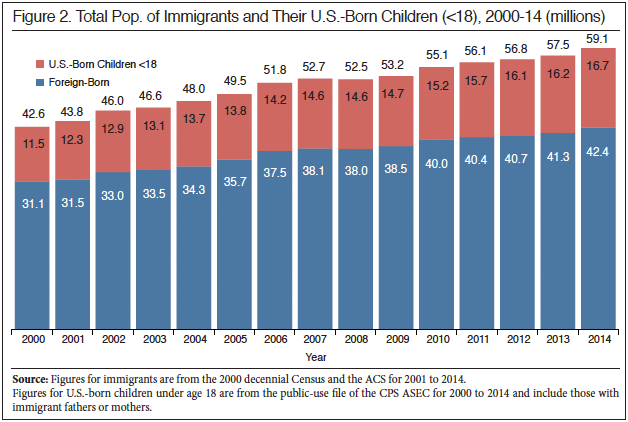

Introduction

This Backgrounder uses the latest Census Bureau data from 2014 and 2015 to provide the reader with information to make sound judgments about the effects of immigration on American society with the hope that it will shed some light on what policy should be in the future. There are many reasons to examine the nation's immigrant population. First, the 59 million immigrants and their U.S.-born children in 2014 comprise nearly one-fifth of U.S. residents. How they are faring is vitally important to the United States. Moreover, understanding how immigrants are doing is the best way to evaluate the impact of immigration on American society. Absent a change in policy, between 12 and 15 million new immigrants (legal and illegal) will likely settle in the United States in the next 10 years. And perhaps 30 million new immigrants will arrive in the next 20 years.1

Immigration policy determines the number allowed in, the selection criteria used to admit them, and the level of resources devoted to controlling illegal immigration. The future, of course, is not set and when deciding on what immigration policy should be it is critically important to know the impact of immigration in recent decades.

There is no single approach to answering the question of whether the country has been well served by its immigration policy. Although not explicitly acknowledged, the two most important ways of examining the immigration issue are what might be called the "immigrant-centric" approach and the "national" approach. They are not mutually exclusive, but they are distinct.

The immigrant-centric approach focuses on how immigrants are faring, or what is sometimes called immigrant adaptation or assimilation. The key assumption underlying this perspective is not so much how immigrants are doing relative to natives, but rather how they are doing given their level of education, language skills, and other aspects of their human capital endowment. This approach also tends to emphasize the progress immigrants make over time on its own terms, and the benefit of migration to the immigrants themselves. The immigrant-centric view is the way most, but by no means all, academic researchers approach the issue.

The other way of thinking about immigration can be called the national perspective, which is focused on the impact immigration is having on American society. This approach implicitly assumes that immigration is supposed to benefit the existing population of American citizens; the benefit immigrants receive by coming here is less important. So, for example, if immigration adds significantly to the population in poverty or using welfare programs, this is seen as a problem, even if immigrants are clearly better off in this country than they would have been back home and are no worse off than natives with the same education. This approach is also focused on possible job competition between immigrants and natives and the effect immigration has on public coffers. In general, the national perspective is the way the American public thinks about the immigration issue.

When thinking about the information presented in this report, it is helpful to keep both perspectives in mind. There is no one best way to think about immigration. By approaching the issue from both points of view, the reader may arrive at a better understanding of the complex issues surround immigration.

Data Sources and Methods

Data Sources. The data for this Backgrounder comes primarily from the 2014 American Community Survey (ACS) and the March 2015 Current Population Survey (CPS). In some cases, for state-specific information we combine the March 2014 and 2015 CPS to get a larger, more statistically robust sample. The 3/8 file of the March 2014 CPS was chosen as this is compatible with the March 2015 CPS for income and poverty statistics.2 The ACS and CPS have become the two most important sources of data on the size, growth, and socio-economic characteristics of the nation's immigrant population. In this report, the terms foreign-born and immigrant are used synonymously. Immigrants are persons living in the United States who were not American citizens at birth. This includes naturalized American citizens, legal permanent residents (green card holders), illegal aliens, and people on long-term temporary visas, such as foreign students or guestworkers, who respond to the ACS or CPS.3 We use the terms illegal alien and illegal immigrant interchangeability. The 2014 and 2015 March CPS files were downloaded from the Data Ferret website provided by the Census Bureau. Historical files in Figure 2 (2000-2013) were downloaded from IPUMS.

The public-use sample of the 2014 ACS used in this study has roughly 3.1 million respondents, nearly 360,000 of whom are immigrants. It is by far the largest survey conducted by the U.S. Census Bureau. The ACS includes all persons in the United States, including those in institutions such as prisons and nursing homes. Because of its size and it more complete coverage of the total population, we use the ACS in this report for the overall number of immigrants and their year of arrival at the national and state level. Because it includes questions on language and public school enrollment not found in the CPS, we also use the ACS to examine these issues. Although the ACS is an invaluable source of information on the foreign-born, it contains fewer questions than the CPS. The 2014 ACS file was downloaded from IPUMS.

The March Current Population Survey, which is called the Annual Social and Economic Supplement, includes an extra-large sample of minorities. The survey is abbreviated as the CPS ASEC or just the ASEC. While much smaller than the ACS, the CPS ASEC still includes about 200,000 individuals, more than 26,000 of whom are foreign-born. Because the CPS contains more questions, it allows for more detailed analysis in some areas than the ACS. The CPS has been in operation much longer than the ACS and for many years it has been the primary source of data on the labor market characteristics, income, health insurance coverage, and welfare use of the American population. The CPS is also one of the only government surveys to include questions on the birthplace of each respondent's parent, allowing for generational analysis of immigrants and the descendants of immigrants.

Another advantage of the CPS, unlike the ACS, is that every household in the survey receives an interview (phone or in-person) from a Census Bureau employee.4 Like the ACS, the CPS is weighted to reflect the actual size of the total U.S. population. Unlike the ACS, the CPS does not include those in institutions and so does not cover the nation's entire population. However, those in institutions are generally not part of the labor market, nor are they typically included in statistics on health insurance coverage, poverty, income, and welfare use.

The ACS and CPS each have different strengths. By using both in this report we hope to provide a more complete picture of the nation's foreign-born. However, it must be remembered that some percentage of the foreign-born (especially illegal aliens) are missed by government surveys of this kind, thus the actual size of the population is somewhat larger than what is reported here. There is research indicating that some 5 percent of the immigrant population is missed by Census Bureau surveys.5

Historical Trends in Immigration

Immigration has clearly played an important role in American history. Figure 1 reports the number and percentage of immigrants living in the United States from 1900 to 2014. The figure shows very significant growth in the foreign-born both in absolute numbers and as a share of the total population since 1970. The immigrant population in 2014 stood at 42.4 million in the ACS. The Department of Homeland Security estimates that 1.85 million immigrants are missed in the ACS. 6 So the actual number of immigrants may have been 44.25 million in 2014. Even without accounting for those missed by the Census Bureau, it is still the case that the foreign-born population in 2014 has more than doubled since 1990, tripled since 1980, and quadrupled since 1970, when it stood at 9.6 million. The increase in the size of the immigrant population has been so dramatic (22.6 million) since 1990 that just this growth is double the size of the entire foreign-born population in 1970 or even 1900.

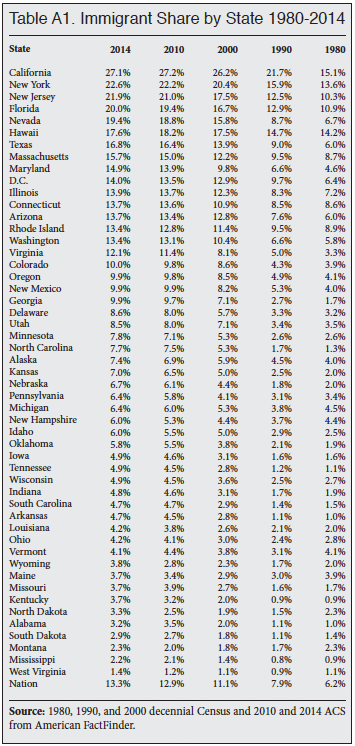

While the number of immigrants in the country is higher than at any time in American history, the immigrant share of the population in 2014 (13.3 percent) was somewhat higher a century ago. Absent a change in policy, the number and share of immigrants in the population will continue to increase for the foreseeable future. The most recent Census Bureau projections indicate that by 2023 the foreign-born share of the U.S. population will reach 14.8 percent, the highest percentage in American history. Moreover, the share of the population will continued to increase through 2060, according the Census Bureau.7

In terms of the impact of immigrants on the United States, both the percentage of the population made up of immigrants and the number of immigrants are clearly important. The ability to assimilate and incorporate immigrants is partly dependent on the relative sizes of the native and immigrant populations. On the other hand, absolute numbers also clearly matter; a large number of immigrants could create the critical mass necessary to foster linguistic and cultural isolation regardless of their percentage of the overall population. Whether one focuses on numbers or population share, the growth of the foreign-born population in recent decades is extraordinary and the latest projections indicate that the country is headed into uncharted territory.

Recent Trends in Immigration

Total Numbers. Figure 2 reports the size of the foreign-born population from 2000 to 2014 based on the ACS and the number of children (<18) with immigrant fathers or mothers based on the CPS.8 The figure shows significant growth during the last 14 years. Figure 2 shows a significant fall-off in the growth of the immigrant population from 2007 to 2009, with an increase of only 450,000 over that two-year period. This slowing in the growth likely reflects a reduction in the number of new immigrants (legal and illegal) settling in the country and an increase in out-migration. The deterioration in the U.S. economy coupled with stepped-up enforcement efforts at the end of the Bush administration almost certainly accounts for much of this decline. In a series of reports looking that this time period, the Center for Immigration Studies estimated immigration and emigration rates throughout the decade. In general, our prior research found good evidence that the level of new immigration fell at the end of the decade and that out-migration increased.9 Since 2012, growth in the foreign-born population has picked up, increasing by 1.7 million in the two years prior to 2014. Figure 2 also shows that the number of U.S.-born children of immigrants under age 18 has also increased significantly.

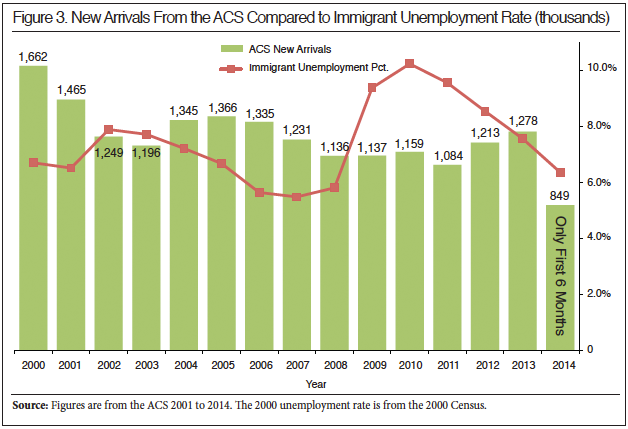

Flow of New Immigrants. Another way to examine trends in immigration is to look at responses to the year-of-arrival question. Figure 3 reports new arrivals based on the ACS from 2000 to 2014. (The ACS for each year provides complete arrival data for the preceding calendar year, so, for example, arrival figures for 2013 are from the 2014 ACS and the figures for 2012 are from the 2013 ACS.) Data for 2014 is only for the first six months of that year, as the ACS reflects the U.S. population as of July 1. Figure 3 also reports the unemployment rate for immigrants during the same time period. The figure indicates that the number of new arrivals was higher in the first part of the decade relative to the end of the decade. But the key finding is that immigration remained very high, even when immigrant unemployment increased dramatically.

Over the entire period 2000 to 2014, 18.7 million new immigrants arrived. Figure 3 also shows that, despite the Great Recession, which began at the end of 2007, and the weak economic growth that followed it, 7.9 million new immigrants still settled in the United States from the beginning of 2008 to mid-2014. This is an enormous flow of new people entering the country during a steep recession and relatively weak recovery. During the very worst of the economic downturn, 2008 to 2011, Figure 3 still shows 4.5 million new immigrants settled in the country.

The results in Figure 3 are a reminder that immigration is a complex process; it is not simply a function of labor-market conditions in the United States. While the state of the U.S. economy can impact the pace of immigration, the desire to be with relatives or to enjoy greater political freedom and lower levels of official corruption also play a significant role in the decision to come to the United States. The generosity of America's public benefits and the quality of public services also make this country an attractive place to settle. These things do not change during a recession, even a steep one.

Figure 3 also shows an increase in new arrivals 2011 to 2013. This fact, and the increase in growth 2012 to 2014 already discussed in Figure 2, supports the idea that immigration maybe rebounding — with more immigrants arriving and perhaps fewer returning home each year.

It is worth pointing out that the results in Figure 3 do not exactly match some of the tables in this report when we report figures by decade of arrival for the immigrant population in 2014. For example, in Table 1 we show 5.2 million immigrants living in the country who arrived in 2010 or later. Yet, Figure 3 indicates that 5.58 million arrived 2010 to 2014. The difference reflects return migration and deaths among those who arrived 2010 to 2014. The difference also reflects sampling variability for both sets of numbers.10

Mortality Among the Foreign-Born. By definition, no one born in the United States is foreign-born and so births cannot add to the immigrant population. Moreover, each year some immigrants die and others return home. There is some debate about the size of out-migration, but together deaths and return-migration should equal about 1.5 percent of the immigrant population annually, or roughly 600,000 a year. (Note that this estimate of deaths and out-migration applies to the entire foreign-born population, not just new arrivals.) For the foreign-born population to grow, new immigration must exceed deaths and outmigration.

It is possible to estimate deaths and outmigration based on the ACS data. Given the age, gender, race, and ethnic composition of the foreign-born population, the death rate over the last decade should be about seven per 1,000. (These figures include only individuals living in the United States and captured by the ACS, not any deaths that occur among illegal immigrants trying to cross the border illegally.) This means that the number of deaths 2010 to 2014 was 1.15 million, or an average of 288,000 deaths per year.

Net Immigration. Figure 3 shows that new immigration was 5.58 million from 2010 to 2014. However, these figures are for all of 2010 while the growth figures (2.44 million) are from July 1, 2010, to July 1, 2014. Excluding one-half of the new arrivals in 2010 so that arrivals correspond to the growth figures means new immigration from July to July equaled five million. Out-migration can be estimated using the following formula: outmigration = new arrivals – (growth + deaths). Plugging in the numbers we get the following: 1.41 million = 5 million – (2.44 million + 1.15 million). This implies 1.41 million immigrants left the United States during the four years from 2010 to 2014, or about 350,000 annually. Demographers often use the term "net immigration" to describe the difference between new arrivals and those leaving. Based on the above calculations, net immigration was 3.59 million from 2010 to 2014. To estimate net immigration, we subtract new arrivals (five million) from emigration (1.41 million) for net immigration of 3.59 million since 2010. It should be noted that emigration occurs among the entire immigrant population, not just among new arrivals. In fact, most of those leaving the country 2010 to 2014 arrived years earlier.

There are several caveats about these numbers. First, the estimates are for a four-year period and outmigration may have varied from year to year. Second, there is no adjustment for undercount in these numbers, which is not trivial among new arrivals. Third, this approach assumes that growth in the foreign-born population can only be caused by those who report that they are new entrants. In fact, growth can be caused by immigrants returning to the United States after spending time outside of the country. It is not clear what year these returning immigrants will report when asked by the Census Bureau what year they "came to live in the United States".11 Despite these possible sources of error, the level of out-migration and net immigration reported above provides a reasonable estimate of the flow of people into and out of our country.

State Numbers

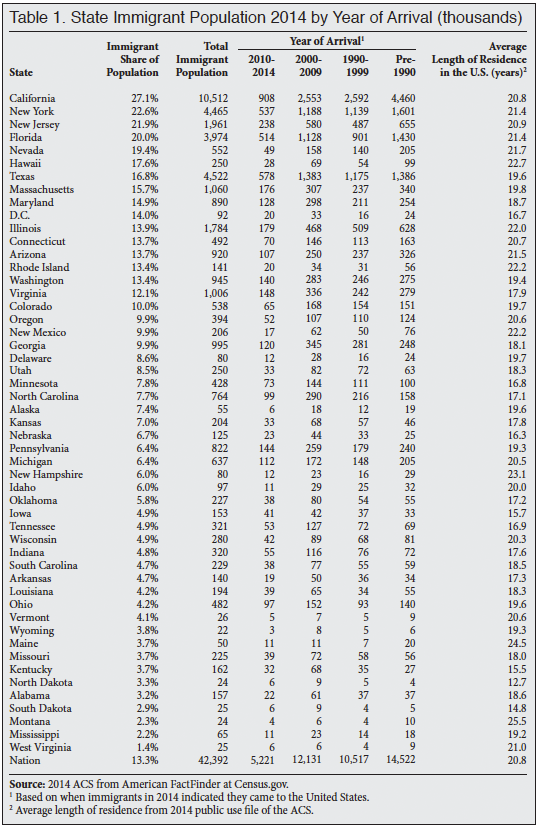

State Data. Table 1 shows the number of immigrants in each state and the share that is immigrant in 2014. California, Texas, New York, Florida, New Jersey, Illinois, Massachusetts, Virginia, Georgia, Washington, Arizona, Maryland, and Pennsylvania have the largest immigrant populations. Each of these states had more than 800,000 foreign-born residents in 2014. California has the largest immigrant population, accounting for one-fourth of the national total. New York and Texas are next with over 10 percent of the nation's immigrants. With 9 percent of the nation's immigrants, Florida's foreign-born population is similar in size. New Jersey and Illinois are next with 5 and 4 percent of the nation's immigrants, respectively. Table 1 shows that the immigrant population is concentrated in relatively few states. Six states account for 64 percent of the nation's foreign-born population, but only 40 percent of the nation's overall population.

Table 1 also reports year of arrival for the foreign-born population in each state in 2014. In 2014, there were 5.2 million immigrants who indicated they had arrived in the United States in 2010 or later. As already discussed, the actual number of new arrivals 2010 to 2014 was higher, but some who came in this period went home or died over this time.

Table 1 shows that the average immigrant has lived in the United States for almost 21 years.12 Thus the immigrant population in the United States is comprised mostly of long-time residents. This is important: As will become clear in this report, immigrants have much higher rates of poverty, uninsurance, and welfare use and lower incomes and rates of home ownership. However, the economic status of the immigrant population is not because they are mostly new arrivals.

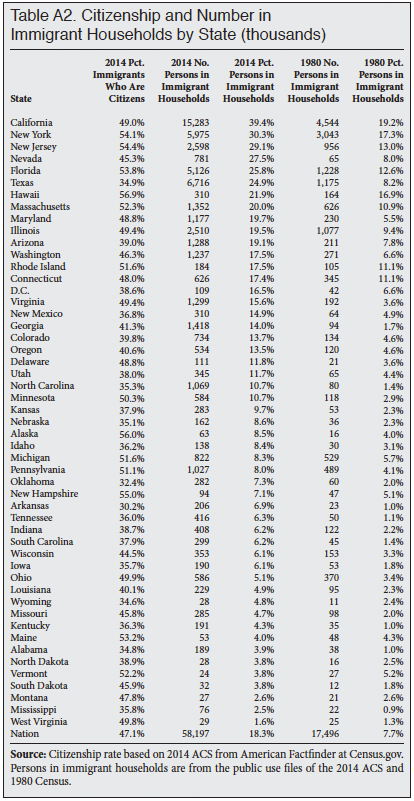

Looking at the immigrant share of each state's population shows that in general many of the states with the largest immigrant populations are also those with the highest foreign-born shares. However, several smaller states such as Hawaii and Nevada rank high in terms of the percentage of their populations that is foreign-born, even though the overall number of immigrants is more modest relative to larger states. Table A.1 in the appendix at the end of this report shows the immigrant share of each state's population from 1980 to 2014. Table A.2 in the appendix shows citizenship rates and the number of persons in immigrant households by state.

In addition to total numbers, Table 1 shows the immigrant populations by state based on their year of arrival, grouped by decade. Table 2 reports the size of state immigrant populations in 2014, 2010, 2000, and 1990. While the immigrant population remains concentrated, it has become less so over time. In 1990, California accounted for 33 percent of the foreign-born, but by 2000 it was 28 percent and by 2014 it was 25 percent of the total. If we look at the top six states of immigrant settlement, they accounted for 73 percent of the total foreign-born in 1990, 68 percent in 2000, and 64 percent in 2014.

Table 2 also shows there were nine states (10 if we count the District of Columbia) where the growth in the immigrant population was more than twice the national average of 6 percent over the last four years. These states were North Dakota (45 percent), Wyoming (42 percent), Montana (19 percent), Kentucky (15 percent), New Hampshire (14 percent), Minnesota and West Virginia (both 13 percent), and Louisiana and Utah (both 12 percent). It is worth noting that the growth rate in California, the state with the largest immigrant population growth, was about 4 percent, lower than the national average. Table 2 makes clear that the nation's immigrant population has grown very dramatically outside of traditional areas of immigrant settlement like California.

Immigrants by Country of Birth

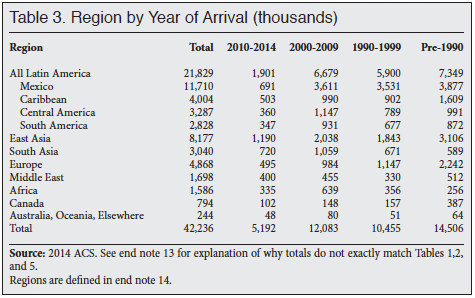

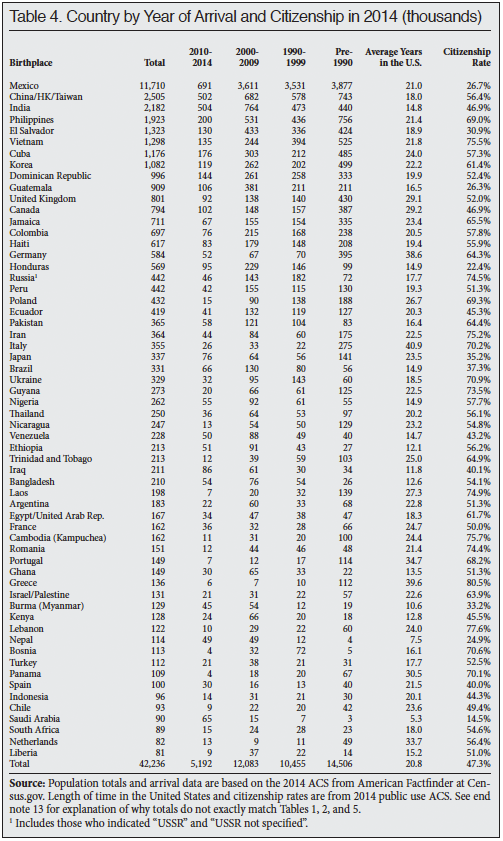

Tables 3, 4, and 5 report immigrant figures in 2014 by region and country of birth and the year they came to the United States.13 Table 3 shows regions of the world by year of arrival, with Mexico and Canada reported separately.14 Latin America accounts for almost 52 percent of immigrants overall. In terms of the number of post-2010 immigrants, 37 percent of those who came 2010 to 2014 are from Latin America (Mexico, Central America, South America and the Caribbean). Table 4 reports the top immigrant-sending countries in 2014. In terms of sending the most immigrants 2010 to 2014, Mexico, India, China, the Philippines, Cuba, the Dominican Republic, and Vietnam were the top countries.

Table 4 also reports the number of immigrants from each country who arrived in 2010 or later. Thus, the table reads as follows: 5.9 percent of Mexican immigrants in 2014 indicated in the survey that they arrived in 2010 or later. For immigrants from Saudi Arabia, 72 percent arrived in 2010 or later. Countries such as Nepal (43 percent), Iraq (41 percent), Burma (35 percent), and Spain (30 percent) had higher percentages of recent arrivals. In contrast, for countries like Poland and Laos, few are recent arrivals. Table 5 shows the top sending countries in 2014 and those same countries in 2010, 2000, and 1990. Table 5 shows that, among the top sending countries, those with the largest percentage increase in their immigrant populations in the United States from 2010 to 2014 were Saudi Arabia (93 percent), Bangladesh (37 percent), Iraq (36 percent), Egypt (25 percent), and Pakistan, India, and Ethiopia (all 24 percent). This compares to an overall growth rate of 6 percent during the time period.

Population Growth

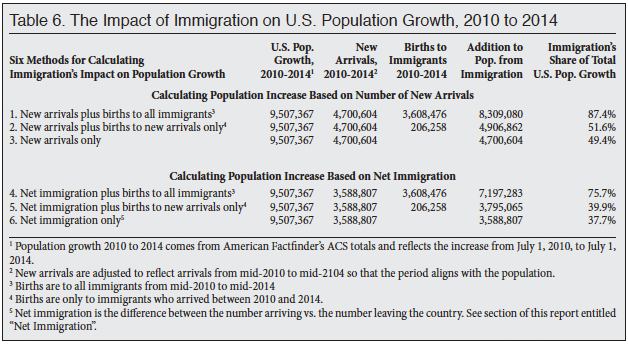

The ACS can be used to provide insight into the impact of immigration on the size of the U.S. population. Table 6 reports six different methods using the 2014 ACS to estimate the effect of immigration on U.S. population growth since 2010. The first column in the table shows that between July 2010 and July 2014, the U.S. population grew by 9.5 million people. The first three rows of Table 6 use the number of immigrants who arrived in the United States in the last four years, and are still in the country, to estimate the impact of immigration on U.S. population growth. In 2014, there were 5.2 million immigrants who indicated that they had entered the country in 2010 or later. That is, they came to the country in this time period and have not left the country.15

Because arrival numbers from the ACS are for January 1, 2010, to July 2014, we adjusted new arrivals by subtracting half of those who arrived in 2010 from this total so that new arrivals from mid-2010 to mid-2014 total 4.7 million and comport with the period of time that is measured by population growth figures. Of course, immigrants do not just add to the population by their presence in the United States.

Based on the 2014 ACS, there were 3.6 million births to immigrants in the United States over the last four years.16 The top of Table 6 adds the 4.7 million new arrivals to the 3.6 million births for a total of 8.3 million additions to the U.S. population from immigration. This equals 87.4 percent of U.S. population growth from July 2010 to July 2014. Not all births during the decade to immigrants where to those who arrived 2010 to 2014. Method 2 reports that of the 3.6 million births during the decade, just 206,258 were to immigrants who arrived during the time period. (Not surprisingly, most births were to immigrants who arrived before 2010.) If we add those born to new arrivals to the number of new entrants, we get 4.9 million additions to the U.S. population, or 51.6 percent of population growth.

The lower part of Table 6 uses net immigration instead of new arrivals to estimate the impact of immigration on population growth. As discussed in the section on deaths and outmigration, our rough estimate is that net immigration from 2010 to 2014 was 3.6 million. This is the difference in the number arriving and the number leaving. If we add net immigration to total immigrant births during the decade it equals 7.2 million, or 75.7 percent of population growth, as shown in Method 4. Method 5 uses net immigration and the number of births to new immigrants for a total addition of 3.8 million, which equals 39.9 percent of population growth. Net immigration by itself equals 37.7 percent of population growth, as shown in Method 6.

It may be worth noting that growth in the immigrant population of roughly 2.4 million (see Figure 1) is not an accurate way of assessing the impact of immigration policy on population size because it includes deaths that are not a function of policy and are not connected with new arrivals.17 Table 6 makes clear that whether new immigration or net immigration is used to estimate the impact, immigration policy has very significant implications for U.S. population growth.

The same data used in Table 6 not only provides an estimate of immigration's impact on population growth, it has other uses as well. For example, if we wished to allow the current level of immigration, but still wished to stabilize the U.S. population by reducing native fertility, we can roughly estimate what it would take based on the table. In 2014, there were about 15.4 million children living in the country who were born to natives 2010 to 2014. As shown above, immigration added 8.3 million to the U.S. population. To offset these additions, it would have required 8.3 million fewer births to natives, or roughly a reduction in native fertility of about half. Since the native-born population already has slightly below replacement level fertility, to advocate a one-half reduction in their fertility to accommodate immigration seems impractical in the extreme.

Characteristics

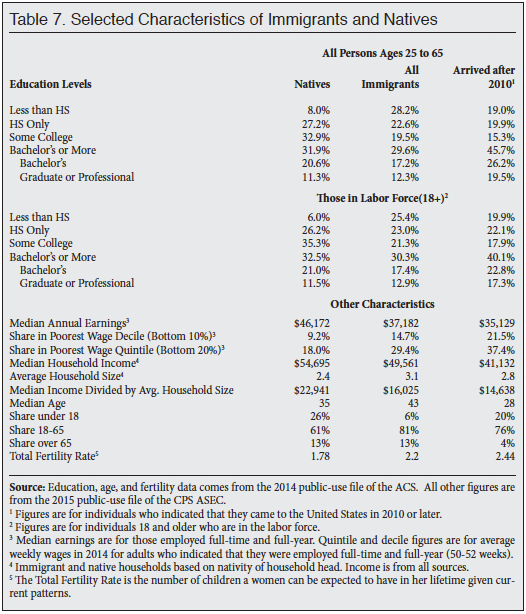

Educational Attainment. Table 7 reports the education level of immigrants and natives. The top of the table reports figures for all persons ages 25 to 65. Based on the 2014 ACS, about 28 percent of immigrants 25 to 65 have not completed high school, compared to 8 percent of natives. This difference in the educational attainment of immigrants and natives has enormous implications for the social and economic integration of immigrants into American society. There is no single better predictor of economic success in modern America than one's education level. As we will see, the fact that so many adult immigrants have little education means their income, poverty rates, welfare use, and other measures of economic attainment lag well behind natives.

Table 7 also shows that a slightly larger share of natives has a bachelor's degree than immigrants, and the share with a post-graduate degree is almost identical for the two groups. Historically, immigrants enjoyed a significant advantage in terms of having at least a college education. In 1970, for example, 18 percent of immigrants had at least a college degree, compared to 12 percent of natives.18 This advantage at the top end has now entirely disappeared.

The middle of the Table 7 reports education level only for adults in the labor force.19 The figures are not entirely the same because those who are in the labor force age (18 and older) differ somewhat from the entire population (ages 25 to 65) in their educational attainment. For example, the least-educated natives in particular are much less likely to be in the labor force — working or looking for work. The right side of the table reports figures for those immigrants who arrived in 2010 or later. More recently arrived immigrants are significantly more educated than immigrants overall, with 40 percent of new arrivals having at least a college degree. However, it is still the case that new immigrants are about three times as likely to lack a high school education as natives. The increase in the education of new immigrants almost certainly reflects at least in part the decline of illegal immigration. Whether this large increase in immigrant skills is a temporary or permanent change is unknown.

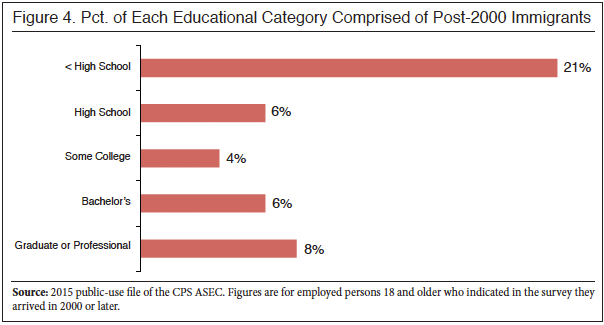

Overall, 16.8 percent of workers are immigrants and this is somewhat higher than their 13.3 percent share of the total U.S. population because, in comparison to natives, a slightly larger percentage of immigrants are of working age. The large number of immigrants with low levels of education means that immigration policy has dramatically increased the supply of workers with less than a high school degree, while increasing other educational categories more moderately. This is important because it is an indication of which American workers face the most job competition from foreign workers.

While immigrants comprise 16.8 percent of the adult total workforce, they comprise almost half (47.6 percent) of adults in the labor force who have not completed high school. Figure 4 shows how recently arrived immigrants have increased the supply of different types of workers. It reports the number of immigrants who arrived in 2000 or later divided by the total number of workers in each educational category (immigrant and native). Thus, the figure shows that post-2000 immigrants have increased the supply of dropout workers by 21 percent, compared to 4 to 8 percent in other educational categories. This means that any effect immigration may have on the wages or job opportunities of natives will disproportionately affect the least educated native-born workers.

Income and Wages. In this report we show figures for both earnings and income. Earnings are income from work, while income can be from any source, such as working, investments, or rental property. Given the large proportion of immigrants with few years of schooling, it is not surprising that the income figures reported at the bottom of Table 7 show that, as a group, immigrants have lower median earnings than natives.20 (Earnings from the CPS are based on annual income from work in the calendar year prior to the survey.) The annual median earnings of immigrants who work full-time and year-round are only about 81 percent those of natives. And for the most recent immigrants, median earnings are 76 percent those of natives. Another way to think about immigrants and natives in the labor market is to examine the share of immigrants and natives who work for low wages. In 2015, 14.7 percent of immigrants were in this bottom wage decile, compared to 9.2 percent of natives. If we examine the weekly wages for the poorest fifth of the labor market, 29.4 percent of immigrants fall into the bottom quintile, compared to 18 percent of native-born full time year round workers.

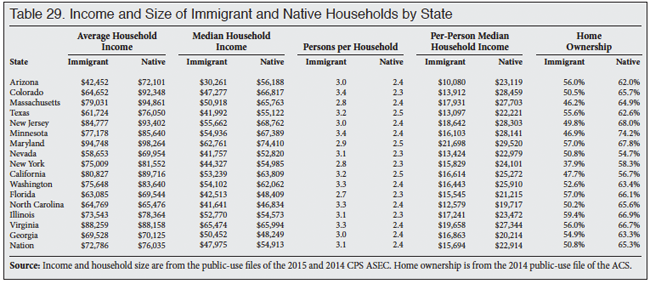

Household Income. Another way to think about the relative position of immigrants compared to natives is to look at household income. The bottom of Table 7 reports that the median household income of immigrant-headed households is $49,561, which is 91 percent that of the household income of natives — $54,695. In addition to having lower incomes, immigrant households are 30 percent larger on average than native households — 3.09 persons vs. 2.38 persons. As a result, the per capita household median income of immigrants is only 70 percent that of natives — $16,025 vs. $22,941. This is important not only as a measure of their relative socio-economic standing, but also because it has fiscal implications. Lower household income means that in general immigrant households are likely to pay somewhat less in taxes than native households. This is especially true for progressive taxes, such as state and federal income taxes, which take into account income and the number of dependents. Larger household size also means that, in general, immigrant households will use somewhat more in services than native households. Since households are the primary basis on which taxes are assessed and public benefits distributed in the United States, the lower income and larger size of immigrant households has implications for public coffers.

Age of Immigrants. The bottom of Table 7 shows that in 2014 the median age of an immigrant was 43, compared to a median of 35 for natives. The median overall age in the United States was 37. The fact that immigrants have a higher median age is a reminder that although immigrants may arrive relatively young, they age over time like everyone else. The bottom of Table 7 also shows that 13 percent of both immigrants and natives are over age 65. This, too, is a reminder that immigrants age. The idea that immigration is a solution to an aging society is largely misplaced partly because of the simple fact that immigrants age over time.

Those who argue that immigration will fundamentally change the age structure generally have in mind new arrivals. In 2014, the median age of an immigrant who arrived in 2010 or later was 28, compared to 35 for natives. Looking at the newest arrivals, those who came in 2013 or the first half of 2014, had a median age of 27. This confirms the common belief that immigrants are younger than natives at arrival, but the difference with natives is not enormous. The presence of these new immigrants has little impact on the age structure. If, for example, the 5.2 million immigrants who arrived in 2010 or later are removed from the data, the median age in the United States would still be 37 years.

But four years of immigration is not very long and the above analysis does not include children born to immigrants. If we remove from the 2014 ACS the 17.3 million immigrants who arrived since 2000 plus their 3.9 million native-born children, the median age in the United States would be 38 years.21 Again this compares to 37 years when post 2000 immigrants and their children are included. This means that the full impact of post-2000 immigration on the median age in the United States was to reduce it by only one year.22However, median age is probably not the best way to think about this question.

The main concern with an aging society is that there will not be enough people of working age to pay for government or support the economy. We can estimate the overall impact of immigration on the age structure by looking at the share of the population that is of working-age (16 to 65) using the 2014 ACS. In 2014, 66.2 percent of the total population was 16 to 65. If all 17.3 million immigrants in 2014 who indicated that they arrived in 2000 or later are removed from the data, 65.1 percent of the population would be of working age. If we remove post-2000 immigrants plus their 3.9 million native-born children, 66 percent of the U.S. population would be of working age. Again, this compares to 66.2 percent when these immigrants and their children are included. Clearly, the impact of immigration on the share of the population that is of working age is quite small. Immigration adds to the working-age population, but it also adds to the population too old or too young to work.

The modest size of the impact on aging is especially apparent when we consider that post-2000 immigration plus births to these new immigrants added some 21.2 million new people to the U.S. population. Even immigration and births to immigrants of this scale only has a small impact on changing the nation's age structure.

One of the reasons immigration will also have a modest impact on aging going forward is shown at the bottom of Table 7. Immigrant fertility is not that much higher than that of natives. The total fertility rate (TFR) of immigrant women in 2014 was 2.2 children, compared to 1.78 for natives. TFR is a measure of fertility used by demographers to measure the number of children a woman can be expected to have in her lifetime given current patterns.23 The ACS asks all women in their childbearing years if they had a child in the last year, so it is a straightforward matter to calculate fertility using the survey.

The total fertility rate in the United States (immigrant and native) is 1.85. Without immigrants the rate would be the TFR for natives of 1.78. Thus, the presences of immigrants raises the TFR of the country by .08 — about 4 percent.24 While immigrants do tend to arrive relatively young and have somewhat higher fertility rates than natives, immigrants age just like everyone else, and the differences with natives are not large enough to fundamentally alter the nation's age structure. Demographers, the people who study human populations, have long known this is the case.

In an important 1992 article in Demography, the leading academic journal in the field, economist Carl Schmertmann explained that, mathematically, "constant inflows of immigrants, even at relatively young ages, do not necessarily rejuvenate low-fertility populations. In fact, immigration may even contribute to population aging."25 The Census Bureau also concluded in projections done in 2000 that immigration is a "highly inefficient" means for increasing the percentage of the population that is of working-age in the long run.26 In a paper presented at the annual meeting of the Population Association of America in 2012 by myself and several co-authors, we also showed that immigration has only a small impact on aging, but a large impact on the size of the U.S. population.27 There is a clear consensus among demographers that immigration has a positive but small impact on the aging of society like ours. A simple analysis of the ACS data confirms this conclusion.

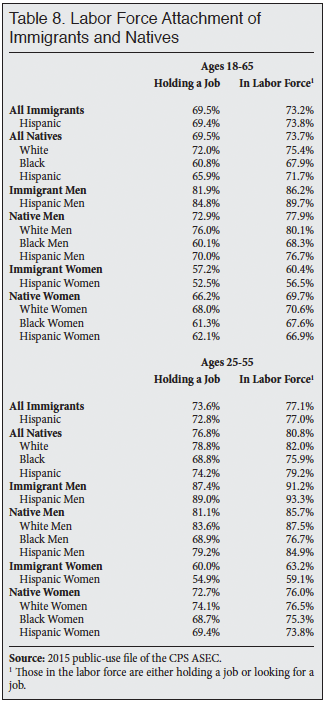

Labor Force Attachment. Table 8 shows the share of immigrant and native-born men and women holding a job or in the labor force based on the March 2015 CPS. Those in the labor force have a job or are looking for a job.28 The top of the table reports figures for persons 18 to 65 and the lower portion of the table provides the same figures for those in the primary working years of 25 to 55 — when rates of employment tend to be the highest. The table shows that immigrants and natives (18 to 65) overall have virtually identical rates of employment and labor force participation. However, male immigrants have higher rates of employment and labor force participation than native-born men, while female immigrants have lower rates than their native-born counterparts.

For those in the prime working years of 25 to 55, Table 8 shows that the overall rates of native employment and labor force participation are somewhat higher than for immigrants. But male immigrants 25 to 55 are still more likely to work or be looking for work than native-born men. In contrast, native-born women in the primary employment years are much more likely to work than are foreign-born women. As is discussed throughout this report, immigrants' income, health insurance coverage, home ownership, and other measures of socio-economic status lag well behind those of natives. But Table 8 shows that these problems are not caused by immigrants being unwilling to work. Immigrant men in particular have a strong attachment to the labor market.

Occupational Distribution. Table 9 shows the occupational concentration of immigrants and natives. The major occupational categories are shown in bold and ranked based on immigrant share, shown in the first column. The numbers in the second and third columns show natives and immigrants in each occupation (whether working or looking for work in the occupation). The table shows several important facts about U.S. immigration. First, there are millions of native-born Americans employed in occupations that have high concentrations of immigrants. While immigrants certainly are concentrated in particular occupations, it is simply not correct to say that immigrants only do jobs natives don't want. There are more than 25 million native-born Americans in the occupational categories of farming/fishing/forestry, building cleaning/maintenance, construction, production, and food service and preparation. A second interesting findings in Table 9 is that in these top immigrant occupations unemployment for natives averaged almost 10.2 percent in 2014, compared to 6.0 percent nationally.

It is hard to argue that there are no Americans willing to work in these high-immigrant professions. Perhaps the native-born workers are not where employers want, or there is some other reason businesses find these unemployed natives unacceptable, but on its face Table 9 indicates that there are quite a lot of Americans willing to work at jobs that are often thought to be high-immigrant occupations.

A third interesting finding in Table 9 is the enormous variation in the immigrant share of different occupations. Less than 7 percent of lawyers are foreign-born. Only about 5 percent of reporters working for English-language media outlets are immigrants, as are fewer than 6 percent of farmers and ranchers. In contrast, roughly half of maids and a third of butchers and construction laborers are foreign-born. This uneven distribution across occupations means that some Americans face a good deal more competition from immigrant workers, while others face very little. This distribution not only has economic implications, but also may help to explain the politics of immigration. Reporters and lawyers are important opinion leaders in our society, and they face relatively little competition from immigrants.

It would be a mistake to think that every job taken by an immigrant is a job lost by a native. Many factors impact labor market outcomes. But, it would also be a mistake to assume that dramatically increasing the number of workers in these occupations as a result of immigration policy has no impact on the wages or employment prospects of natives.

Poverty, Welfare, and the Uninsured

Poverty Among Immigrants and Natives. The first column in Table 10 reports the poverty rate for immigrants by country and the second column shows the figures when their U.S.-born children under age 18 are included with their immigrant parents.29 Based on the March 2015 CPS, 18.5 percent of immigrants, compared to 13.5 percent of natives, lived in poverty in 2014.30 (Poverty statistics from the CPS are based on annual income in the calendar year prior to the survey and reflect family size.) The higher incidence of poverty among immigrants as a group has increased the overall size of the population living in poverty. In 2014, 16.7 percent of those in poverty in the country were immigrants.

In some reports, the U.S.-born children of immigrants are counted with natives. But it makes more sense to include these children with their immigrant parents because the poverty rate of minor children reflects their parents' income. Overall, in the United States there are 59 million immigrants and U.S.-born children (under 18) with either an immigrant father or mother. In the analysis of poverty and insurance coverage in this report we focus on the 56.4 million immigrants and their children (under 18) with an immigrant father. Those with an immigrant mother and a native-born father are counted with natives. In this way, we avoid overstating the impact of immigration. It should be noted that if those with only an immigrant mother are added to the poverty totals for immigrants and their children it would add slightly to poverty associated with immigrants.

The second column in Table 10 includes the U.S.-born children (under 18) of immigrant fathers. Table 10 shows that the poverty rate for immigrants and their U.S.-born children was 20.7 percent, compared to the 13.5 percent for natives and their young children. (The figures for natives exclude the U.S.-born minor children of immigrant fathers.)

The data by country and region indicate that there is an enormous variation in poverty rates among immigrants from different countries.31 For example, the 29.5 percent of Mexican immigrants and their U.S.-born children living in poverty is many times the rate associated with immigrants from countries such as India and the Philippines.

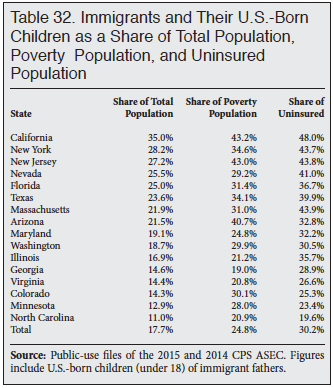

Of the 46.7 million people in the United States living in poverty in 2014 (based on the 2015 data), 11.7 million or 25 percent are immigrants or the U.S.-born children (under 18) of immigrant fathers. Among persons under age 18 living in poverty, 30 percent are either immigrants or the young children of an immigrant fathers. Immigration policy has significantly added to the population in poverty in the United States.

In or Near Poverty. In addition to poverty, Table 10 also reports the percentage of immigrants and natives living in or near poverty, with near-poverty defined as income less than 200 percent of the poverty threshold. Examining those with incomes under 200 percent of poverty is an important measure of socio-economic status because those under this income generally do not pay federal or state income tax and typically qualify for a host of means-tested programs. As is the case with poverty, near-poverty is much more common among immigrants than natives. Table 10 shows that 41.9 percent of immigrants compared to 30.8 percent of natives live in or near poverty. (Like the figures for poverty, the figures for natives exclude the U.S.-born minor children of immigrant fathers.) If the U.S.-born children of immigrants are included with their immigrant parents, the immigrant rate is 45.2 percent. Among the young children of immigrants (under 18), 55.2 percent live in or near poverty, in contrast to 39 percent of the children of natives. In total, 25.5 million immigrants and their young children live in or near poverty. As a share of all persons in or near poverty, immigrants and their young children account for 24.2 percent.

Without Health Insurance. Table 11 reports the percentage of immigrants and natives who were uninsured for all of 2014. (The CPS asks about health insurance in the calendar year prior to the survey.) The table shows that lack of health insurance is a significant problem for immigrants from many different countries and regions. Overall, 21.4 percent of the foreign-born lack health insurance, compared to 8.8 percent of natives. (Like the figures for poverty, Table 11 excludes the U.S.-born minor children of immigrant fathers from the figures for natives.) Immigrants account for 27.3 percent of all uninsured persons in the United States. This compares to their 13.3 percent share of the total population in the 2015 CPS. If the young (under 18) U.S.-born children of immigrant fathers are included with their parents, the share without health insurance is 17.9 percent. The share of children who are uninsured is lower than for their parents mainly because the U.S.-born children of immigrants are eligible for Medicaid, the health insurance program for the poor. Thus, the inclusion of the U.S.-born children pulls down the rate of uninsured immigrants slightly. In total there are 10.1 million uninsured immigrants and their young U.S.-born children in the country, accounting for 30.6 percent of all persons without health insurance. This is dramatically higher than their 17.8 percent share of the total population.

The low rate of insurance coverage associated with immigrants is very much related to their much lower levels of education. Because of the limited value of their labor in an economy that increasingly demands educated workers, many immigrants hold jobs that do not offer health insurance, and their low incomes make it very difficult for them to purchase insurance on their own. A larger uninsured population cannot help but strain the resources of those who provide services to the uninsured already here. Moreover, those with insurance have to pay higher premiums as health care providers pass along some of the costs of treating the uninsured to paying customers. Taxpayers are also affected as federal, state, and local governments struggle to provide care to the growing ranks of the uninsured. There can be no doubt that by dramatically increasing the size of the uninsured population our immigration policy has wide ranging effects on the nation's health care system.

Do Uninsured Immigrants Cost Less? One study found that after controlling for such factors as education, age, and race, uninsured immigrants impose somewhat lower costs than uninsured natives. However, when the authors simply compared uninsured immigrants to uninsured natives the cost differences were not statistically significant. In other words, when using the actual traits that immigrants have, the costs that uninsured immigrants create were the same as uninsured natives.32 It seems likely that uninsured immigrants do cost less than uninsured natives because the immigrants are more likely to be in younger age cohorts where use of health care is less. Of course even if the average uninsured immigrant costs less than the average uninsured native, the difference would have to be enormous to offset the fact that immigrants are almost 2.5 times more likely to be uninsured than native-born Americans.

Immigration and Growth in the Uninsured. Because of Medicaid expansion and direct and indirect subsidies under the Affordable Care Act (ACA), the number of uninsured people has declined in recent years. While the costs and benefits of the ACA are not part of this analysis, we can say that prior to the act immigration played a very large role in the growth of the uninsured population. New immigrants and their U.S.-born children accounted for about two-thirds of the growth in the uninsured from 2000 to 2011.33 Thus to a significant extent the growth in the uninsured in the United States, which was one of the primary arguments for the ACA, was driven by the nation's immigration policies.

Uninsured or on Medicaid. The 2015 CPS shows that 27.1 percent of immigrants and their U.S.-born children under 18 are on Medicaid, compared to 17.9 percent of natives and their children.34 Thus, the large share of immigrants and their U.S.-born children who are uninsured is not due to their being unable to access Medicaid per se. Their use of Medicaid is actually higher than that of natives. It is true that unlike natives, illegal immigrants are not supposed to be enrolled in the program unless they are pregnant and most new legal immigrants are barred as well. Nonetheless, despite these prohibitions, more immigrants and their children use Medicaid than do natives and their children. One reason for this is that the overwhelming majority of legal immigrants have been in the country long enough to access the program.

Combining the uninsured and those on Medicaid together shows that 45 percent of immigrants and their young children (under 18) either have no insurance or have it provided to them through the Medicaid system, compared to 26.7 percent for natives and their children. These numbers are a clear indication of the enormous impact immigration has on publicly financed health care.

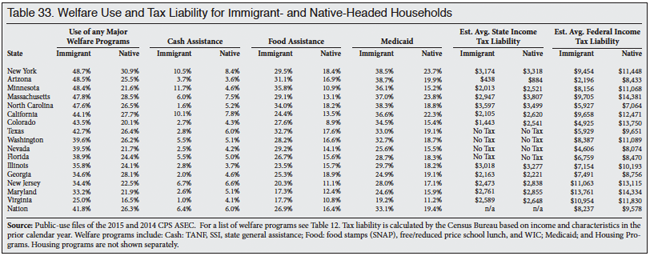

Welfare Use. As the Census Bureau does in many of its publications, we report welfare use based on whether the head of the household is immigrant or native.35 With regard to immigrant households, this means we are mainly reporting welfare use for immigrants and their U.S.-born children who live with them and comparing them to natives and their children. Table 12 shows the percentage of immigrant- and native-headed households in which one or more members uses a welfare program(s). The definition of programs is as follows: cash assistance: Temporary Assistance to Needy Families (TANF), state-administered general assistance, and Supplemental Security Income (SSI), which is for low-income elderly and disabled persons; food assistance: Supplemental Nutrition Assistance Program (SNAP, informally know as food stamps), free and subsidized school lunch, and the Women, Infants, and Children nutrition program (WIC); housing assistance: subsidized and government-owned housing. The table also shows figures for Medicaid use, the health insurance program for those with low incomes.

Table 12 shows that use of food assistance is significantly higher for immigrant households than it is for native households — 27.3 percent vs. 15.9 percent. The same is also true for Medicaid, 33.6 percent of immigrant households have one or more persons using the program compared to 20.3 percent of native households. From the point of view of the cost to taxpayers, use of Medicaid by immigrants and their dependent children is the most problematic because that program costs more than the combined total for the other welfare programs listed.

Use of cash tends to be quite similar for immigrant and native households. Thus if by "welfare" one only means cash assistance programs, then the CPS ASEC shows immigrant use is roughly the same as natives. Of course, there is the question of whether native use of welfare is the proper yardstick by which to measure immigrants. If immigration is supposed to be a benefit, our admission criteria should, with the exception of refugees, select only those immigrants who are self-sufficient. Table 12 shows that welfare use, even of cash programs, is not at or near zero.

As was the case with lower income and higher poverty rates, the higher welfare use rates by immigrant households are at least partly explained by the large proportion of immigrants with few years of schooling. Less educated people tend to have lower incomes. Therefore, it is not surprising that immigrant household use of the welfare system is significantly higher than that of natives for some types of programs.

Under-Reporting of Welfare Use. While welfare use rates are quite high for many sending countries, there is general agreement that the CPS ASEC actually understates welfare use. We know this because the number of people who report in the survey that they are using particular programs is a good deal less than the number shown in administrative data. There is another Census Bureau survey called the Survey of Income and Program Participation specifically designed to capture welfare use and it does a significantly better job of reporting welfare use than any other Census survey, including the CPS ASEC. An extensive analysis comparing administrative data to eight different government surveys conducted for the Department of Health and Human Services (HHS) concluded that the "SIPP performs much better than other surveys in identifying program participants."36 Other research shows the same thing.37 Unfortunately, the SIPP is not released on timely basis like the CPS, nor does the public-use SIPP report individuals' sending-countries.

In an extensive report done by the Center for Immigration Studies using the SIPP we found that in 2012 (the most recent SIPP available) 51.3 percent of immigrant households used one or more welfare programs, compared to 30.2 percent of native households. Data from the CPS ASEC for the same year showed 38.5 percent for immigrants and 24 percent for natives.38 If we adjust up the overall welfare use rates from Table 12 to reflect the likely undercount based on the SIPP, it would imply that 56.6 percent of immigrants used one or more welfare programs as did 33.8 percent of natives. The programs listed in Table 12 cost the government well over $700 billion annually and this is a reminder that immigration has important implications for public coffers.

Use of the EITC and ACTC. In addition to welfare programs, Table 12 reports the share of households in which at least one worker is eligible for the Earned Income Tax Credit (EITC) and the refundable portion of the Additional Child Tax Credit (ACTC).39 Based primarily on income and number of dependents, the Census Bureau calculates eligibility for these programs and includes this information in the public-use CPS files. Workers receiving the EITC pay no federal income tax and instead receive cash assistance from the government based on their earnings and family size. The ACTC works in the same fashion, except that to receive it, one must have at least one dependent child. The IRS will process the EITC and ACTC automatically for persons who file a return and qualify. Even illegal aliens sometimes receive the EITC and ACTC. This is especially true of the ACTC because the IRS has determined that illegals are allowed to receive it, even if they do not have a valid Social Security number. To receive the EITC, one must have a valid Social Security number. With an annual cost of over $40 billion for the EITC and $35 billion for the ACTC, the two programs constitute the nation's largest means-tested cash programs for low-income workers.

Table 12 shows that 23.5 percent of immigrant-headed households have enough dependents and low enough income to qualify for the EITC and 17.2 percent have low enough incomes to receive the ACTC. This compares to 10.9 and 6.9 percent respectively for natives. As already stated, the figures for the EITC and ACTC probably overstate receipt of the programs for both immigrants and natives because they are imputed by the Census Bureau. This is in contrast to the welfare programs listed, which are based on self-reporting by survey respondents, though as already discussed welfare use is underreported in the CPS ASEC.

Given the low education level of so many immigrants it is not surprising that a large share work, but that their incomes are low enough to qualify for the EITC and ACTC. It important to understand that the high rate of EITC and ACTC eligibility does not reflect a lack of work on the part of immigrants. In fact, one must work to be eligible for them. Nor does the relatively high use of welfare programs reflect a lack of work on the part of immigrants. In 2014, 82.8 percent of immigrant households had at least one worker, compared to 74.3 percent of native households. Work in no way precludes welfare use and it is required to receive the EITC and ACTC. The high rate of welfare use by immigrant households should also not be seen as moral failing. Like all advanced industrial democracies, the United States has a well-developed welfare state. This fact coupled with an immigration system that admits large numbers of immigrants with modest levels of education and tolerates large-scale illegal immigration is what explains the figures in Table 12.

In short, many immigrants come to America to find a job and have children. Their low incomes mean that many are unable to support their own children and so turn to taxpayers to help support them. While that does not mean that immigrants come to American to get welfare, many immigrants do use these programs, creating large costs for taxpayers.

Welfare Use by Country and Region. Table 12 shows that immigrants from some countries have lower welfare use rates than natives while those from other countries have much higher use rates. Mexican, Honduran, and Dominican households have welfare use rates that are much higher than natives — even higher than for refugee-sending countries like Russia and Cuba. In fact, if one excludes the primary refugee-sending countries, as shown in the bottom portion of Table 12, the share of immigrant households using a welfare program remains virtually unchanged at 42.1 percent.40 Refugees are simply not a large enough share of the foreign-born, nor are their rates high enough to explain the level of welfare use by immigrant households. Or put a different way, the relatively large share of immigrant households using welfare is not caused by refugees.

Welfare for Households with Children. The bottom of Table 12 makes a number of different comparisons between immigrant and native households. Households with children have among the highest welfare use rates. The share of immigrant households with children using at least one major welfare program is high — 60.3 percent. The share of native households with children using welfare is also very high. But the figures for immigrants do mean that a very large share of immigrants come to America and have children but are unable to support them. As a result, immigrant households with children make extensive use of food assistance and Medicaid. This raises the important question of whether it makes sense to allow the large-scale settlement of immigrants who are unable to support their own children.

Welfare Use Among Working Households. The bottom of Table 12 shows the share of households with at least one worker using welfare. The table shows that 41.7 percent of immigrant households with at least one working person still use the welfare system. This compares to 24.5 percent of native households with at least one worker. Most immigrant households have at least one person who worked in 2014. And as we have already seen, immigrant men in particular have high rates of work. But this in no way means they will not access the welfare system, particularly non-cash programs, because the system is designed to provide assistance to low-come workers with children and this describes a very large share of immigrant households.

Given their education levels, and relatively large family size, many immigrant households work and use the welfare system. In fact, of immigrant households using the welfare system, 82.8 percent had at least one worker during the year. For native households, it was 74.3 percent. All of this is a very important reminder that bringing less-educated workers to fill low-wage jobs rather than relying on the supply of less-educated workers already in the country can create very large costs for taxpayers.

Entrepreneurship

Self-Employment. Table 13 examines the self-employment rates of immigrants and natives. The table shows that immigrants and natives exhibit remarkably similar levels of entrepreneurship, at least when measured by self-employment rates. The table shows that 11.4 percent of immigrants and 11.1 percent of natives are self employed. Some people argue that immigrants are more likely to start businesses than natives. If true, the self-employment rates indicate that their businesses may fail at higher rates so that in term of overall rates of entrepreneurship the rates of immigrants and natives are nearly identical. Entrepreneurship is neither lacking nor a distinguishing characteristic of the nation's immigrants. If one removed immigrants from the data, the overall rate of self-employment in the United States would be about the same. Of course, the table also shows that immigrants from some countries do have very high rates of self-employment, while others have very low rates.

The bottom of Table 13 reports the share of immigrants and natives who have a part-time business. That is, they report self-employment income, but do not indicate that this is their primary employment. Natives are slightly more likely than immigrants to be self-employed part-time — 1.7 percent vs. 1 percent. Overall, 12.8 percent of natives and 12.4 percent of immigrants are self-employed full- or part-time. Again, this is a tiny difference.

Turning to self-employment income, we see that the average self-employment income (revenue minus expenses) of immigrants is slightly higher than that of natives, though the average is quite low for both groups. It seems likely that operators of small business are very reluctant to provide the government with information about their business income and this at least partly explains the very low reported income for both groups in Table 13. The table also reports the share of entrepreneurs whose businesses have more than 10 employees. Self-employed natives are somewhat more likely to have larger business than self-employed immigrants — 19.1 percent vs. 16 percent. But this still means that the vast majority of immigrant and native business are small. Like self-employment rates and income, in general the CPS shows little difference in the number of employees for immigrant and native entrepreneurs.

Households, Home Ownership, and Language

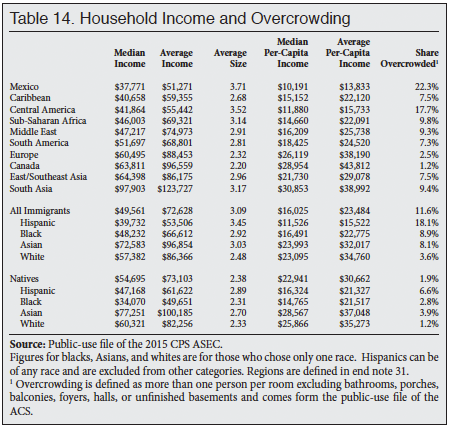

Household Income. Table 14 shows average and median household income. The average household income of immigrant households is only slightly lower than that of native households. Turning to median income, the table shows a larger difference, with immigrant households having income that is 10 percent below that of natives. The larger difference between median and mean is almost certainly due to income among immigrants being somewhat more skewed than native income, with a large share of immigrant households on the high and low income extremes. As discussed earlier in this report, Table 14 shows there is a large difference with natives in per-capita household income, whether it is calculated by dividing median or mean income by household size. Immigrant households are 30 percent larger than native households. Per-capita median household income for natives is $6,916 (43 percent) higher than per-capita median immigrant household income. Per-capita mean household income for natives is $7,178 (31 percent) higher than that of immigrants. Immigrant household income does not differ that much from native household income, but because the households are much larger on average, their per-capita income is much lower.

Table 14 also shows large differences in income for immigrants by country and sending region. Immigrants from Canada and South Asia have very high household incomes, while those from Mexico, Central America, Sub-Saharan Africa, and the Caribbean tend to have relatively low incomes. It is worth noting that while the average income of some immigrant groups, such as South Asians, is much higher than that of natives, the per-capita household income is closer to that of natives because many of these immigrant groups have larger households on average than natives.

Overcrowded Households. There are several possible measures of what constitutes an overcrowded household. The Department of Housing and Urban Development has compiled a detailed summary of the overcrowding literature and the various ways to measure it.41 Most researchers define a household as overcrowded when there is more than one person per room. The analysis that follows uses this standard definition of dividing the number of rooms in the housing unit by the number of people who live there. The ACS records the number of rooms by asking respondents how many separate rooms are in their house or apartment, excluding bathrooms, porches, balconies, foyers, halls, or unfinished basements. Dividing the number of rooms in a household by the number of people living there determines if the household is overcrowded.

Overcrowding is a problem for several reasons. First, it can create congestion, traffic, parking problems, and other issues for neighborhoods and communities. Second, it can strain social services because the local system of taxation is based on the assumption that households will have the appropriate number of residents. Third, like poverty it can be an indication of social deprivation.

The far right column in Table 14 shows the share of households that are overcrowded for households headed by immigrants and natives.42 The 2014 ACS shows that 11.6 percent of immigrant-headed households are overcrowded, compared to 1.9 percent of native households. Because immigrant households are so much more likely to be overcrowded, they account for a very large share of such households. In 2014, immigrant-headed households accounted for 51 percent of overcrowded households, even though they are only 14.6 percent of all households. Table 14 shows that overcrowding varies significantly by sending region. Relatively few households headed by Canadians and Europeans are overcrowded. In contrast, it is quite common among immigrants from Mexico and Central America.

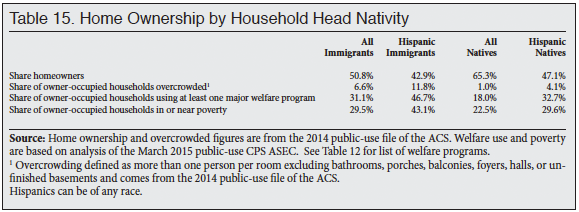

Home Ownership. Owning a home has long been an important part of the American dream. Table 15 reports home ownership for immigrant and native households and some of the characteristics of those households.43 There is a very significant difference in home ownership rates between immigrants and natives. Overall, Table 15 shows that 50.8 percent of immigrant households are owner-occupied, compared to 65.3 percent of native-headed households. While it may seem that home ownership is a clear sign of belonging to the middle class, Table 15 shows that for immigrant households in particular this may not always be the case.

The table shows that overcrowding is much more common among owner-occupied immigrant households, with 6.6 percent being overcrowded, compared to just 1 percent of owner-occupied native households. While 6.6 percent is not a large percentage, it does mean that roughly one out of 15 owner-occupied immigrant households is overcrowded, compared to one out of a hundred for native households. The table also shows that 31.1 percent of owner-occupied immigrant households used at least one major welfare program, compared to 18 percent of native households. A somewhat larger share of immigrant households also has low incomes, with 29.5 percent below 200 percent of poverty, compared to 22.5 percent of native homeowners. Thus it would be a mistake to think that home ownership is always associated with being part of the middle class.

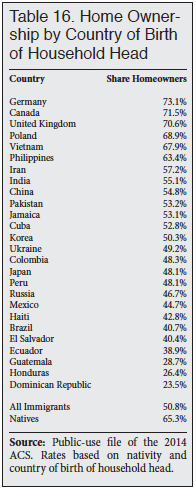

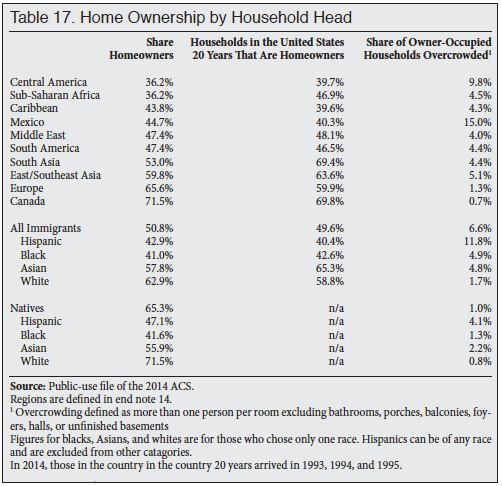

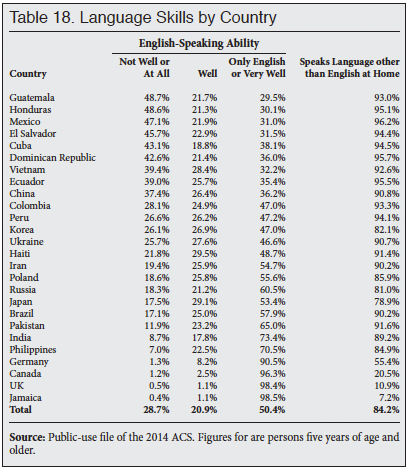

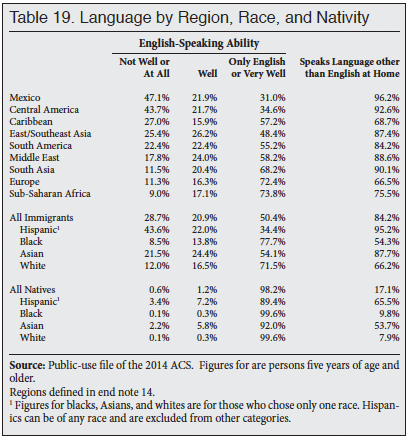

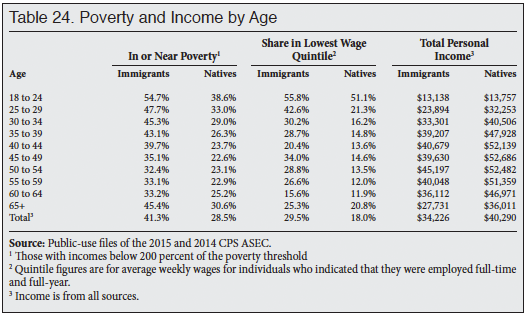

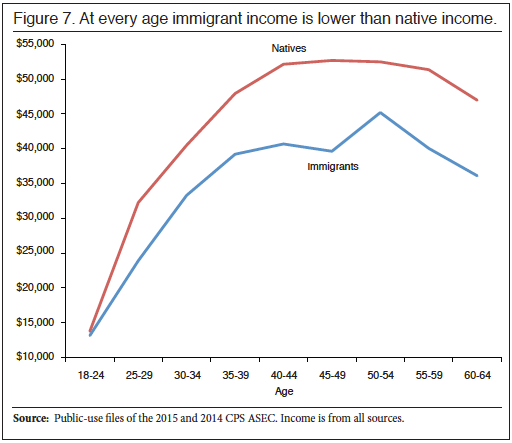

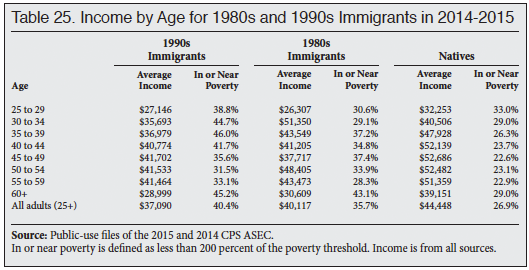

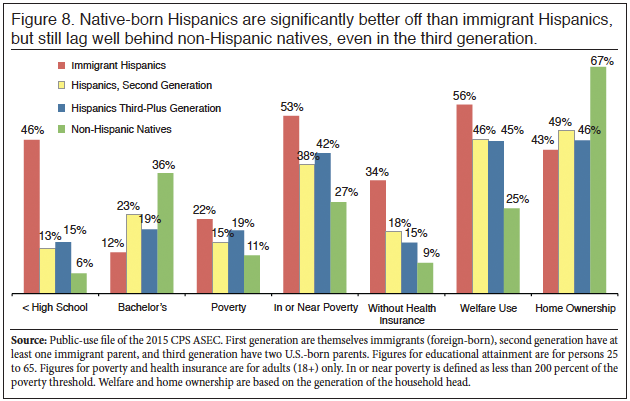

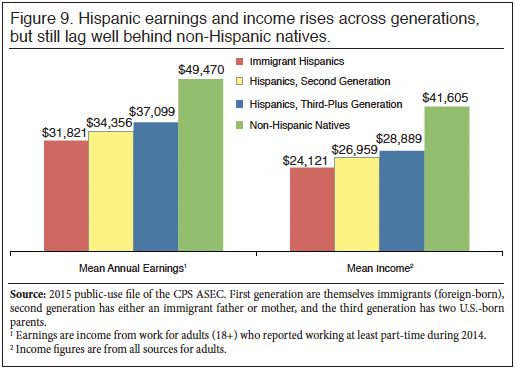

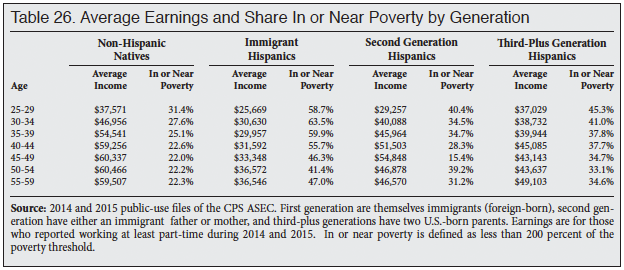

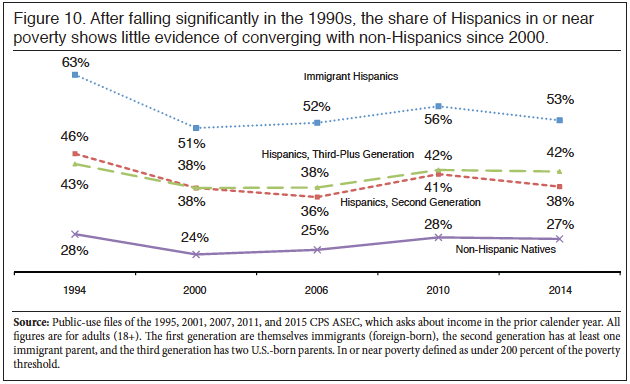

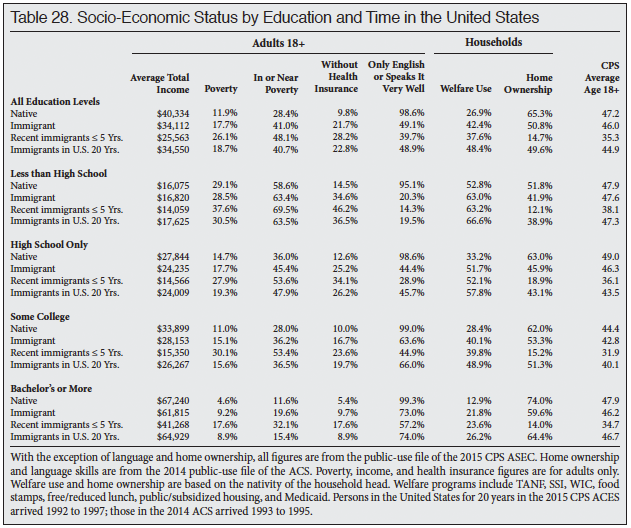

Table 16 shows home ownership rates by country of birth. As with the other socio-demographic characteristics examined so far in this report, there is significant variation by country. For example, the home ownership rate for households headed by German immigrants (73.1 percent) is over three times that of Dominican immigrants (23.5 percent). Table 17 shows home ownership rates by region, race, and ethnicity. In addition to overall rates, Table 17 shows home ownership rates for households headed by immigrants who have been in the country for 20 years.44 The table shows that immigrant households headed by these well-established immigrants have about the same rate of home ownership as immigrants over all. This does not mean that immigrant home ownership does not rise over time. In fact, as we will see later in this report, home ownership does increase significantly the longer immigrants live in the country. What is does mean is that the much lower rate of ownership for immigrants overall is not caused by a large number of new arrivals. Even immigrants who have been in the country for two decades still have substantially lower rates of home ownership than native-headed households.