Live Panel Today at 10am: Afghans in the US

Download a PDF of this Backgrounder.

Steven A. Camarota is the director of research and Karen Zeigler is a demographer at the Center.

The crisis in Afghanistan and the decision to admit tens of thousands of people from that country, with plans to admit more, has raised interest in Afghan immigrants already in the United States. This report uses the latest Census Bureau data to examine where Afghan immigrants live and their education levels, income, employment, fertility, poverty, welfare use, and other sociodemographic characteristics. The findings show that the number of Afghans in this country has grown dramatically in the last decade and that they tend to be concentrated in a relatively few states and cities. It also shows that Afghan men, but not women, have relatively high rates of work. However, reflecting their much lower levels of education, a large share of Afghans live in or near poverty. Although the share with low incomes has not worsened in recent years, their use of non-cash welfare has risen sharply.

Among the findings:

- The number of Afghan immigrants (also referred to as the foreign-born) was 133,000 in 2019, more than triple the 44,000 Afghans in 2000, and nearly 2.5 times the 55,000 Afghans in 2010.

- The states with the largest Afghan-immigrant populations are California (54,000), Virginia (24,000), and Texas (10,000). The metropolitan areas with the largest Afghan populations are Washington, D.C. (26,000), San Francisco, and Sacramento, both with 16,000.

- Since 1980, 79 percent of Afghan immigrants have been admitted for humanitarian reasons — as refugees, asylees, or, since 2008, on Special Immigrant Visas.

- Afghan immigrants have high rates of citizenship, with 81 percent who have lived in the country for more than five years having naturalized, compared to 61 percent of all immigrants.

- The educational level of Afghan immigrants has fallen both in absolute terms and relative to the native-born. The share of Afghans (25-64) with at least a bachelor’s degree fell from 30 percent in 2000 to 26 percent in 2019, while increasing from 27 percent to 35 percent for natives.

- In 2019, the share of all Afghans (18 to 64) employed was only 64 percent, compared to 75 percent for the native-born. This reflects low rates of work among Afghan women. Among Afghan men, 84 percent were employed, higher than the 78 percent for native-born men.

- Many Afghans have low incomes. Of persons in households headed by Afghan immigrants, 25 percent live in poverty — twice the 12 percent for people in native-headed households.

- Although the share of Afghans with low incomes has not worsened in recent years, their use of welfare has increased significantly. In 2019, 65 percent of Afghan households used at least one major program (cash, food stamps, or Medicaid) compared to 50 percent in 2010, while use for native households increased from 22 percent to 24 percent.

- Food stamp use by Afghan households increased the most, from 19 percent to 35 percent between 2010 and 2019, while falling from 11 percent to 10 percent for native-born households.

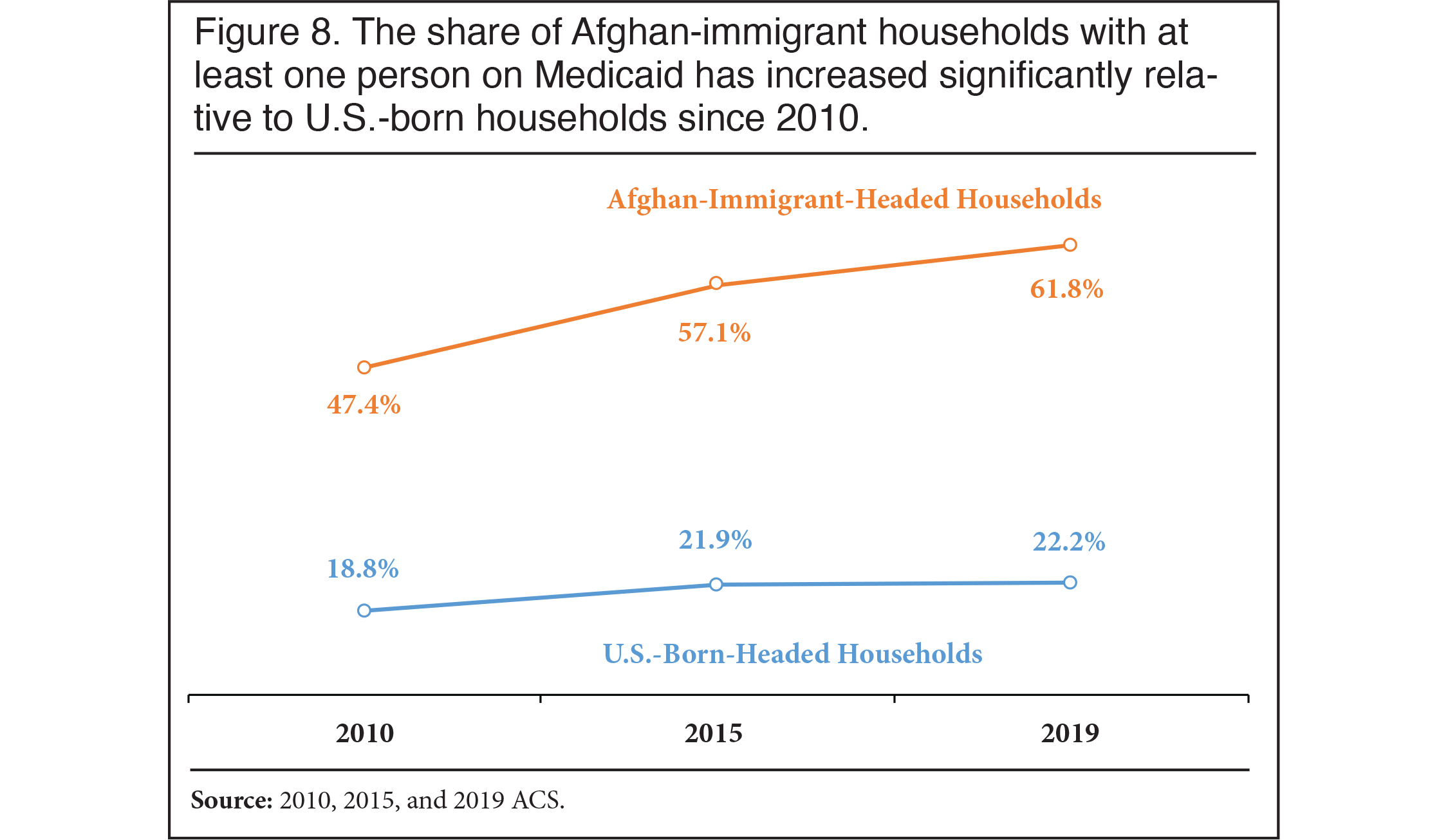

- The share of Afghan households with one or more persons on Medicaid increased from 47 percent to 62 percent over this time period, while increasing from 19 percent to 22 percent for native households.

- The high rates of welfare use reflect the large share of Afghans who live in or near poverty and the success of refugee resettlement organizations in signing them up for programs, helping many assimilate into the welfare system.

- While many Afghans are poor and access welfare, a significant share also have high incomes. Of full-time Afghan-immigrant workers, one out of nine earned at least $100,000 a year in 2019; this compares to one out of seven for the native-born.

- The birth rate of Afghan women (ages 15-44) was 155 per thousand in 2019 — nearly three times the 56 per thousand for native-born women.

- At 35 percent, the share of children in Afghan households who live in poverty is more than twice the 16 percent for children in native-born households.

Introduction

The collapse of the Afghan government after the withdrawal of U.S. troops from that country has prompted many Afghan nationals to attempt to leave their homeland and settle in the United States. The U.S. State Department reported that 123,000 people were evacuated from Afghanistan, including 6,000 American citizens; the rest were Afghan nationals. It’s not clear if all of these Afghans have come or will be coming to the United States. Toward the end of the evacuation operation, the New York Times reported that at least a-quarter-million Afghan nationals remained in the country and could be eligible for Special Immigrant Visas (SIVs) due to their associations with the U.S. government. Absent a change in U.S. policy, it seems certain that for many years to come thousands of refugees, asylum seekers, family-sponsored immigrants, and others will be coming from Afghanistan to the United States, as has been the case after other conflicts in which the U.S. was involved, such as Vietnam and Korea.

Given the rapidly growing population of Afghan immigrants, their integration and incorporation into American society is increasingly important. The best insight we have of how they are faring and their impact on American society comes from Census Bureau data. This report uses the public-use files of the American Community Survey (ACS) and the 2000 decennial census to examine Afghan immigrants already in the United States. (The 2019 ACS being the most recent available.) We use the terms “immigrant” and “foreign-born” synonymously in this report to mean all persons who were not U.S. citizens at birth, which includes naturalized citizens, permanent residents, illegal immigrants, and temporary visitors such as foreign students and guestworkers. We also use the terms “native”, “native-born”, and “U.S.-born” interchangeably for those who were U.S. citizens at birth, which includes those born to American citizen parents abroad and those born in Puerto Rico and other U.S. territories.

Overall Numbers

Figure 1 shows that the number of immigrants from Afghanistan has grown dramatically since 2010. The number of Afghan immigrants in the United States grew modestly from 2000 to 2010, but nearly tripled from 2010 to 2019. Figure 2 shows the increase in the number of foreign-born Afghans, reflecting a significant increase in the number of permanent residents in the country since 2010. Most Afghan immigrants admitted since the 1980s have been admitted for humanitarian reasons — refugees, asylees, or, since 2008, on the Special Immigrant Visa program. The SIV program is for individuals who worked for the U.S. government in Iraq or Afghanistan and are now in danger because of this association. The share coming on humanitarian grounds has fluctuated from year to year, but since 1980, 79 percent of all green cards for Afghan nationals have been for humanitarian reasons.

Table 1 shows the number and share of all Afghan immigrants living in the top five states and metropolitan areas of settlement. California has by far the largest population of Afghans, with 41 percent living in the Golden State. While California is also the top state of settlement for all immigrants, in 2019 it accounted for only 24 percent of all immigrants. The top five states of Afghan settlement account for 80 percent of all immigrants from that country in the United States. This is also much more concentrated than the 54 percent living in the top five states of settlement for all immigrants (not shown in Table 1). Clearly, Afghans are much more concentrated than is the immigrant population overall. Table 1 also shows the largest metropolitan areas of Afghan settlement, with the Washington, D.C., area having more immigrants from Afghanistan than any other U.S. metro area. In terms of growth, all of the cities and states shown in Table 1 have seen dramatic increases in the number of Afghan immigrants just since 2015.

Average Age, Time in U.S., Citizenship, and Education

Table 2 provides a profile of immigrants from Afghanistan. The top of the table shows that immigrants from Afghanistan tend to be recent arrivals, are somewhat younger than native-born Americans, and have high rates of marriage and citizenship relative to other immigrants. They also tend to have high fertility rates. A large share of Afghans have not graduated from high school (22.1 percent), compared to 6.9 percent of the native-born. The share with at least a bachelor’s degree is less than that of the native-born. Education is perhaps the single best predictor of the socioeconomic status of immigrants in the United States. The relatively large share of Afghans with very modest levels of education almost certainly helps explain their high rates of poverty and welfare use discussed later in this report.

Despite being significantly less educated than the native-born, Afghan men ages 18 to 64 are more likely to work, though this is partly because relatively fewer Afghans are ages 18 to 24 compared to the U.S.-born, as most arrived at older ages. Those ages 18 to 24 tend to have lower rates of work as many are still in school. Focusing only on “prime-age” men (25 to 54) shows that Afghan men and natives have very similar rates of employment.

Poverty and Welfare Use

Poverty. Table 3 shows that a much larger share of Afghans live in or near poverty than do the native-born. This is true whether we focus only on adults or include all members of their households. (In 2018, the official poverty threshold for a family of 3 was $20,780. Poverty statistics reflect incomes in 2018 — the year prior to the survey.) Of all persons in Afghan households, 25.4 percent live in poverty and 50.8 percent live in or near poverty, with near poverty defined as less than 200 percent of the poverty threshold. (Those with incomes of less than 200 percent of poverty often qualify for welfare programs and typically pay no federal income tax.) Of children in Afghan households, 35 percent live in poverty, more than twice the share of children in households headed by the U.S.-born. Perhaps equally troubling, 64.3 percent of children in Afghan-immigrant households live in or near poverty. In short, Afghans have high fertility rates, as shown in Table 2, and a very large share of their children live in or near poverty.

As Table 2 shows, a large share of Afghans are newcomers to America. So this partly explains why so many have low incomes. However, poverty is not simply a problem among new arrivals. Of persons in households headed by an Afghan immigrant who arrived from 2000 to 2009, Table 3 shows that 24.2 percent live in poverty and 46.6 percent live in or near poverty. These rates are not that different from Afghan-immigrant households overall; these households are headed by a person who is 42 years old on average who has lived in the United States for 15 years on average. So the large share with low incomes is not simply due to their being young immigrants who just arrived in America.

Income. Table 3 shows that the median income of full-time, year-round Afghan workers is about 16 percent less than native-born workers. So at least when we focus on full-time, year-round workers, the income of Afghan immigrants is not that much lower than the native-born. The average full-time, year-round Afghan worker has been in the country for almost 17 years, so they are not all newcomers by any means. Table 3 also shows that the median earnings of Afghans who arrived between 2000 and 2009 are also about 16 percent less than the median earnings of U.S.-born workers.

Turning to household incomes, we see a much larger difference between Afghans and native-born Americans. Table 3 shows that, overall, households headed by an Afghan immigrant have a median income that is about 32 percent less than natives, which is also a good deal less than the median household income of all immigrants. This may in part reflect the low rate of work among Afghan women (see Table 2). Although Afghan households are 62 percent larger on average than native households (see Table 3), and they have significantly more adults on average as well, they have only about the same number of workers as native households — a little over one on average. The low incomes of Afghan households are even more apparent when we divide the much larger average number of persons in Afghan households by the median household income. The per capita median income of Afghan households is just over $11,000 a year, compared to nearly $27,000 for persons living in households headed by the U.S.-born.

Welfare Use. Table 3 shows that Afghan immigrants have very high rates of use for all three types of welfare that can be measured using the ACS — cash, food, and Medicaid. Given the large share of Afghans who have low incomes, it is not surprising that many Afghan households access the welfare system. Moreover, refugees, unlike other legal immigrants, are immediately eligible for all welfare programs. The fact that Afghan immigrants have high rates of citizenship, which similarly allows access to all programs, likely also has an impact on welfare use. Of course, being a refugee or citizen does not make a person or family use the welfare system per se; to enroll in these programs it is necessary to have an income that allows one to qualify. One also has to be willing to sign up for these programs. (It should be noted that the ACS tends to understate welfare use, which means that the actual level of welfare dependence is higher than reported below.)

Table 3 shows that the 35 percent of Afghan-immigrant-headed households using the Supplemental Nutrition Assistance Program (SNAP), colloquially known as food stamps, is more than three times higher than the 10.4 percent for households headed by the U.S.-born. Afghan use of Medicaid by household is also about three times that used by native-born households. The ratio is also about three to one if we look at individual use of Medicaid. Afghan households’ use of cash programs is nearly five times that of households headed by the U.S.-born. Overall, 65.2 percent of households headed by Afghan immigrants use at least one major welfare program, dramatically higher than the 24.5 percent of native-headed households. These high rates of welfare use would almost certainly be much higher if other programs were included, such as the Women, Infants and Children (WIC) nutrition program, free school lunch, public housing, and the Earned Income Tax Credit. But these programs are not included in the ACS.

It is important to understand that working does not preclude use of welfare if one’s income is low enough. The bottom of Table 3 shows that 64.7 percent of Afghan households with at least one worker access one or more welfare programs, compared to 21.5 percent of working U.S.-born households. Overall, Afghan households are more likely to have at least one worker than households headed by the U.S.-born, but, as already discussed, many of these households access the welfare system anyway. Work and welfare often go together and this is true for immigrants and the U.S.-born alike.

Change Over Time

Educational Attainment Over Time. Figures 3 and 4 show that the educational level of Afghan immigrants has fallen, especially relative to the native-born. The share of Afghans (25-64) with at least a bachelor’s degree fell from 30 percent in 2000 to 26 percent in 2019, while increasing from 27 percent to 35 percent for natives (Figure 3). Figure 4 shows that the share of Afghan immigrants with less than a high school education has not increased significantly since 2000, but the gap with the U.S.-born has widened substantially as the share of those born in America who have completed high school increased over time. Given the importance of educational attainment in determining economic outcomes, the deterioration in the education level of Afghans relative to the native-born is likely to have important implications for how they do in the United States.

Poverty and Near Poverty Over Time. Figures 5 and 6 show that the share of persons in Afghan households living in poverty or near poverty has not changed dramatically in the last two decades, though there have been fluctuations. Nor has it changed much relative to the native-born. This is certainly good news in light of the fact that the education level of Afghans has fallen, especially relative to the native-born. Of course, Figures 5 and 6 do indicate that the share of persons in Afghan-headed households with low incomes has been roughly double the rate of those in native-headed households for nearly 20 years, and the differences have not really narrowed.

Welfare Use Over Time. Although the share of Afghans with low incomes has not worsened in absolute terms or relative to the native-born in recent years, Afghan use of welfare has increased for food stamps, Medicaid, and overall, while use of cash programs shows no clear trend. Figure 7 shows that use of SNAP has exploded among Afghan immigrants, from 18.8 percent in 2010 to 35 percent in 2019, while declining slightly for the native-born. Figure 8 shows that the share of Afghan-headed households with one or more persons on Medicaid increased from 47.4 percent in 2010 to 61.8 percent in 2019, while increasing from 18.8 percent to 22.2 percent for households headed by the U.S.-born. Figure 10 shows that use of at least one of the major welfare programs has increased much more for Afghan-headed households than households headed by the U.S.-born.

This rise in welfare use is somewhat puzzling since the share of Afghans with low incomes has not increased significantly. This means that their use of such programs was not caused by some deterioration in their position. Of course, the share of Afghans who are in or near poverty is very high; however, this has been true for decades. The increase in welfare use, both in absolute terms and relative to the U.S.-born, almost certainly reflects the increased success of refugee agencies in the United States in signing up low-income Afghans for programs. It may also reflect the fact that a much larger Afghan-immigrant concentration creates the critical mass necessary in many parts of the country to disseminate information through the immigrant community about how to navigate the welfare system.

Conclusion

It seems very likely that the number of Afghan immigrants arriving the United States in the coming years is going to be significant, assuming no change in U.S. immigration policy. With the takeover by the Taliban of that country, many are likely to want to leave. The large and growing population of Afghan immigrants in the United States will facilitate this process as immigrants are able to sponsor relatives in Afghanistan for permanent residence under the current immigration system. Moreover, the social networks that help drive migration are likely to play a large role in increasing awareness of conditions in the United States and the desire to come to America among people in Afghanistan. Given the oppressive nature of the new Taliban regime, the Biden administration will also be under political pressure to admit more Afghans on humanitarian grounds as refugees, asylees, parolees, and on Special Immigrant Visas. The Census Bureau data analyzed in this report indicates that a large share of Afghans in this country have modest levels of education, with many living in or near poverty and dependent on the welfare system. It seems likely that a large share of Afghans allowed into the United States in the future will also struggle in a similar manner.

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|