Printable Scorecard: Rate Trump's Upcoming Immigration Proclamation

Download a PDF of this Backgrounder.

Thanks to Jamie Greedan and Kathleen Sharkey for their help in compiling the work visa and work permit statistics.

The grave employment situation created by the pandemic shutdown requires bold, sustained action from the president. As a first step, President Trump issued a proclamation on April 22 suspending the entry of certain immigrants, including some chain migration and employment categories, to help alleviate saturation in the labor market as the nation begins to recuperate from the pandemic shutdown.1 The proclamation further directed the departments of Labor, Homeland Security, and State to propose additional actions "appropriate to stimulate the United States economy and ensure the prioritization, hiring, and employment of United States workers."

With 18.2 million native-born Americans and 4.3 million immigrants now out of work, millions more who have stopped looking for work, and deep uncertainty about the pace and scope of the national recovery, the case for dramatically reducing the number of foreign workers has never been greater.2 The Center for Immigration Studies has prepared a list of 20 recommendations for additional urgent actions the Trump administration should take to reduce the number of work permits and visas and improve the integrity of the temporary work visa programs. These actions could potentially reduce the number of temporary foreign workers by 1.2 million, or nearly 50 percent.

These include putting a hold on all employment visa programs (temporary and permanent) to assess employer needs and labor conditions; examining the operation of these programs to curb fraud and abuse; and preventing employers who have downsized or accepted pandemic relief from the government from sponsoring workers from abroad.

Background

There are several ways non-citizens join the U.S. labor market, including obtaining a green card or immigrant visa; obtaining a temporary work visa; obtaining a work permit after arrival; and settling here illegally. This report deals primarily with the categories of temporary work visas and work permits, as these reportedly are the focus of the upcoming proclamation.

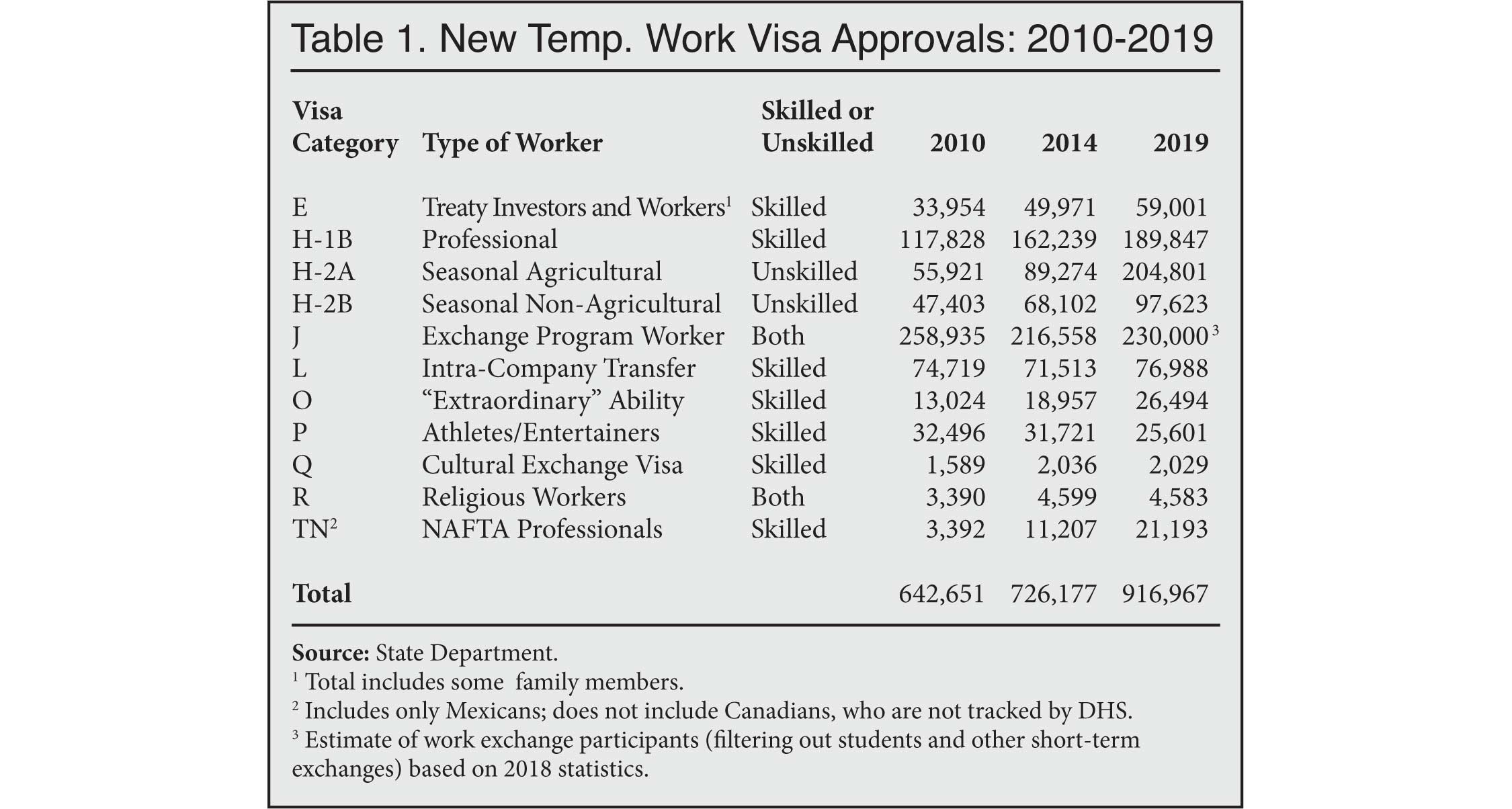

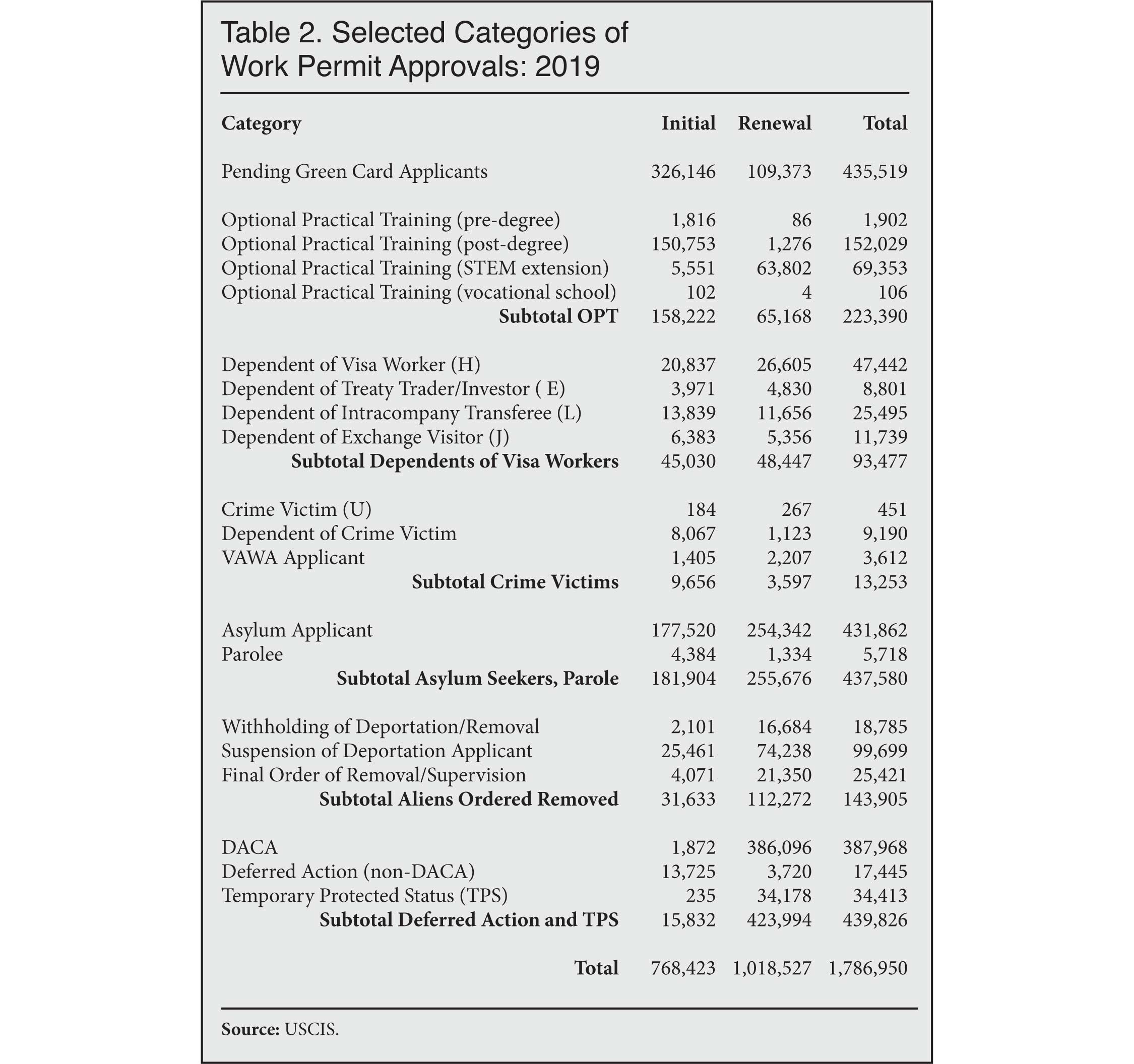

Every year, immigration agencies issue millions of temporary work visas and work permits to non-citizens for periods ranging anywhere from several months to several years. Last year, more than 900,000 new temporary work visas were issued and more than 1.8 million work permits were granted or renewed. These visas and work permit approvals are in addition to new green card and immigrant visa approvals. Due to varying rates of visa and status durations, it is difficult to determine the exact size of the stock population of temporary foreign workers, but we estimate it to be on the order of three to four million workers.

Difference Between Work Visas and Work Permits

The basic distinction between work visas (formally known as non-immigrant visas) and work permits (employment authorization documents, or EADs) is that temporary work visa holders usually arrive from abroad, while the temporary work permit holders typically enter on a non-work visa or illegally and later obtain permission to stay and work, under one of dozens of categories. The main categories of temporary work visas are agricultural and seasonal workers, specialty occupation (H-1B) workers, and exchange program workers. Each category has different requirements, which might include approval from the Department of Labor and U.S. Citizenship and Immigration Services (USCIS). Most temporary visa workers must also obtain a visa from the U.S. State Department at a consulate overseas.

Further details on the number and categories of workers are found in Tables 1 and 3. Visa workers have permission for entry and employment that is inherent to their visa status; they do not need a separate work permit.

|

|

|

In contrast, work permits are for non-citizens who are already in the United States, either without status or in a status that does not directly authorize employment. Examples of work permit grantees without legal status are asylum seekers, crime victims, and deferred action grantees (including DACA). Examples of work permit holders who entered on a non-work visa include students (in Optional Practical Training) and dependents of diplomatic or work visa holders. Work permits are adjudicated by USCIS. In some categories, work permits are essentially granted automatically pursuant to statutory authority from Congress; in others, USCIS has discretion to issue the work permits; others were created without congressional authority. This report recommends executive action to reduce issuances in the discretionary and extra-legal categories.

Table 2 shows the recent figures for selected categories of work permit issuances. These represent more than 90 percent of all work permit issuances.

Although most of the temporary work programs were created by Congress, the president has some discretion to determine or affect how many work visas and permits are granted each year. Unfortunately, for many years some of these programs and categories have operated as if on autopilot, with little oversight or management, and with little to no review of their economic or labor market effects. This has provided an opportunity for employers and labor brokers to find ways to maximize the number of workers they can import from abroad. The lack of oversight of work permits also has enabled presidents to create new de facto legalization or work authorization programs, as in the case of DACA, OPT, and the H-4 EADs.3

Recommendations for Immediate Action

The grave employment situation created by the pandemic shutdown requires bold, sustained action from the president. The actions we propose below should be maintained until the country returns to full employment and full labor force participation for American workers. This will ensure that the employers who have become dependent on these programs, or who have chosen a business model that depends on these programs, are able to adapt. The goal is to break the practices of replacing U.S. workers with visa workers, refusing to hire U.S. workers, or suppressing wages in certain business sectors through importation of cheaper workers.

We propose 20 specific short-term actions to preserve job opportunities for U.S. workers and to prevent U.S. employers from bypassing U.S. workers in the recovery:

- Rescind approval of all labor certifications for pending employment-based immigrant visas and green card/adjustments of status, and require applicants to submit new certification requests for re-adjudication under current labor market conditions.

- Rescind approval of all labor condition attestations (LCAs) for pending employment-based non-immigrant visa applications and require applicants to submit new attestations for re-adjudication under current labor market conditions.

- Suspend adjudication of all Optional Practical Training work permit applications until the economy has recovered (as defined by pre-determined metrics). In the meantime, new regulations and guidance must be promulgated. New rules should include shorter training programs, oversight of training curriculum/plan, a requirement to show that the training is not available in a student's home country, improved monitoring of student and sponsor compliance, and a requirement that employers must pay $5,000 in advance to the Social Security and other payroll tax trust funds for the first year of OPT employment, or $10,000 for the STEM extension employers.4

- Reduce the duration of stay for B-1 short-term business visas to 21 days, unless a visa holder shows a business need requiring a longer stay.

- Deny LCAs/petitions from employers seeking H-1B visa workers at the two lowest wage levels allowed (Level 1 and Level 2 prevailing wages). These are applications on behalf of workers who would be paid less than the median prevailing wage for the occupation and region.

- Suspend approval of all petitions/applications for part-time, seasonal, or peak-load workers. Currently these are allowed in the skilled and unskilled work visa categories.

- Curtail temporary visa renewals and limit extensions to one year.

- Require all employers petitioning for workers after the suspension to maintain a one-to-one match of new U.S. hires for each visa worker hire.

- Suspend adjudication of work permits to H-4 visa holders (dependents of temporary work visa holders) until recovery.

- Suspend adjudication of H-3 (trainee) visas until recovery.

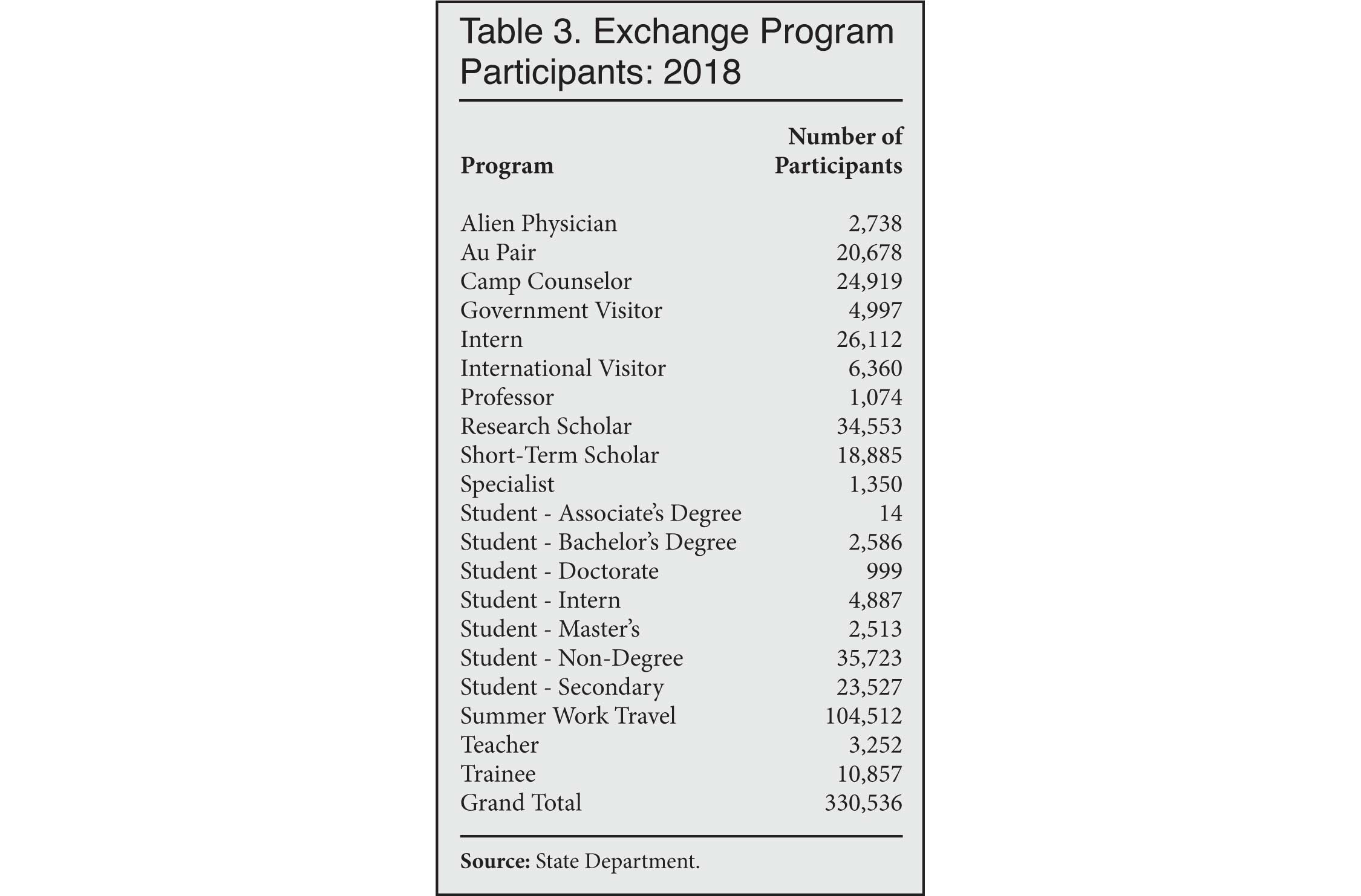

- Curtail adjudication of employment-related exchange (J) visas in the following categories: au pair, camp counselor, intern, trainee, professor, research scholar, summer work/travel, and teacher. (See Table 3 for the number of participants in exchange worker programs), until recovery.

- Curtail adjudication of intracompany transferee (L) visas and petitions until recovery. Create a waiver for employers showing extraordinary need to move the employee to the United States. No waivers for blanket petitions; all applications should be considered individually.

- Suspend adjudication of new E-2 (nonimmigrant investor) visas until the economy has recovered.

- Suspend adjudication of O ("extraordinary ability"), P (athletes and entertainers), and Q (cultural exchange workers) non-immigrant visas until recovery. Create waivers for extraordinary circumstances.

- Suspend adjudication of EB-5 (investor) immigrant visas and adjustment applications.

- Suspend adjudication of all initial "discretionary" EAD (work permit) applications for aliens whose authorization would not be incident to their status, until recovery. Adopt a new requirement for all discretionary EAD renewals based on extraordinary circumstances, extreme hardship, or public interest (such as DACA, abused spouses, etc).

- Implement a public outreach campaign for U.S. workers who have been furloughed by employers who keep visa workers on the job and similar incidents of apparent preference/discrimination in favor of visa workers.

- Refuse to certify or approve replacement temporary workers or work permit holders for any corporate entity that has shut down facilities or substantially curtailed operations because of the pandemic.

- Direct DHS (both FDNS and HSI working hand-in-hand), as well as the Labor and State Departments to institute vigorous pre- and post-audits of 25 percent of the certifications and LCAs submitted by employers seeking foreign laborers across all industries, with at least two purposes in mind: 1) Are the jobs really temporary in nature? And 2) Are there now enough citizen/LPR workers available to fill the jobs? Further direct DOJ to vigorously prosecute cases presented to them by DHS/DOL/DOS where fraud is present.

- Prohibit the distribution of relief funds to employers with a "U.S. person" (meaning U.S. citizens and permanent residents) workforce of less than 50 percent. Prohibit approval of new visas or work permits for employees of companies or businesses that have received Covid-19 relief packages of any kind. Full repayment of such packages would allow the employer to start employing workers receiving new and renewed visas and EADs. This provision would relate to new and extended visas and EADs; there would be no requirement to discharge those aliens who are currently on the payroll with valid documentation during the life of those visas and EADs.

Recommendations for Regulatory Reform

The actions spelled out in this report will create both long-term and temporary job opportunities for hundreds of thousands of unemployed or displaced U.S. workers. However, some cannot be justified beyond the duration of the immediate public health emergency, no matter how helpful to the labor market. U.S. workers need more durable protections that will last beyond the scope of a presidential proclamation, in the form of regulations issued though the conventional administrative rule-making process.

Several transformative regulations already have been drafted, but have been de-prioritized and are stuck in the rule-making pipeline. We recommend the following for priority action:

- Rescind a rule implemented under the Obama administration providing for the issuance of work permits to certain dependents of temporary work visa holders. There is no statutory basis for these work permits, and the program has been challenged in a lawsuit.5 The replacement regulation has been sitting in limbo in the White House for more than a year. Meanwhile, in 2019, more than 45,000 work permits were approved, representing lost job opportunities for U.S. workers.

- Reform the H-1B program, in which more than 180,000 new workers arrived in 2019, joining an estimated 500,000 settled H-1B workers. The workers are approved for white collar, or "knowledge" jobs, most frequently in information technology, but also accounting, nursing, back office administrative work, physical therapy, and more. Employers do not have to show that there is a shortage of workers. Many of the visas are issued to foreign-owned staffing companies who place the foreign workers at U.S. companies to replace existing workers. There is strong evidence that employers are underpaying skilled workers and bringing in relatively modestly skilled workers at comparatively low wages.6

- Reform to the L visa program, which was designed by Congress for multinational companies to transfer managers and executives for temporary assignments in the United States, but which has been used in recent years as a substitute for the more regulated and numerically limited H-1B program.

- Scale back a provision of the Optional Practical Training (OPT) regulation providing for the issuance of work permits to foreign students and graduates. The proposed regulation would rescind an extension of time for foreign STEM graduates implemented by the Obama administration, and would permit such graduates to stay an extra 18 months rather than an extra three years. In addition, it imposes an annual cap on OPT work permits and adds wage and recruitment protections for the foreign workers. With more than 223,000 work permits issued in 2019, the OPT program was the second largest temporary work program, and it has never been approved by Congress. Employers hiring OPT workers are exempt from paying payroll taxes, which adds to their appeal.7 This regulation should correct that loophole, which costs the public approximately $2 billion annually in lost employer contributions to the Medicare, Social Security, and unemployment insurance trust funds.

- Impose stricter controls on nine employment exchange visitor (J-1) programs (physician, au pair, camp counselor, intern, trainee, research scholar, summer work/travel, teacher, and professor), such as numerical caps and wage and recruitment protections. Table 3 shows the number of participants in each of the J programs in 2018.

- Revise the H-2B seasonal employment program to improve oversight of recruitment, wages, and working conditions. In addition, employers should be prohibited from hiring H-2Bs to do the same work that they are employing J-1 summer work/travel exchange participants to do, and vice versa.

- Change the short-term business visitor visa category (B) to regulate the types of work that are permissible. Generally, aliens entering with a B temporary visa are permitted to do work for an overseas employer if they are paid overseas. However, since business visitors are routinely permitted to stay up to six months and apply for a six-month extension, there is abuse of this category; for example, by staffing companies avoiding the restrictions of the H-1B or H-2B category or by Mexican truck drivers, who may obtain the visas to evade restrictions on their U.S. employment. Because most legitimate business visitors stay for less than a month, arriving business visitors routinely should be given a very limited duration of stay unless they provide ample documentation of the need to stay longer.

Finally, the president should pursue legislative reforms. These should take the form of narrow, targeted bills that can attract bipartisan support to address the most obvious problems in these programs, like prohibiting the replacement of U.S. workers with visa workers, reining in executive authority to issue work permits, and ending the EB-5 program and the diversity visa lottery. Eventually a major overhaul of our legal immigration system is needed that would adopt a merit-based selection system for employment immigrants, give greater priority to the most qualified applicants, eliminate extended family categories, and restore annual admissions to a more moderate level that reflects the national interest and supports a modern economy.

End Notes

1 "Proclamation Suspending Entry of Immigrants Who Present Risk to the U.S. Labor Market During the Economic Recovery Following the COVID-19 Outbreak", The White House, April 22, 2020. For analysis, see Jessica Vaughan, "Trump's Immigration Ban May Actually Rev Immigration Back Up: State Dept. had already paused most visa processing, including for the scandalous EB-5 program", Center for Immigration Studies blog, April 23, 2020.

2 Steven A. Camarota, Jason Richwine, and Karen Zeigler, "The Employment Situation of Immigrants and Natives in April 2020: First full month of data after Covid-19 shutdown shows dramatic downturn in employment", Center for Immigration Studies Backgrounder, May 14, 2020.

3 DACA is the acronym for the Deferred Action for Childhood Arrivals program, created by the Obama administration to provide work authorization and protection from deportation for aliens who were settled here illegally before the age of 16 and before 2007. OPT is the Optional Practical Training program, which was first created by the Justice Department in the form of a regulation allowing work permits to be issued to foreign students if required or recommended by the school, and later expanded by the George W. Bush and Obama administrations. The H-4 EADs are work permits granted as a matter of policy choice to the dependents (mostly spouses) of temporary visa workers who are applying for green cards.

4 David North, "Feds Provide Almost $2 Billion in Subsidies to Hire Alien Grads Rather than U.S. Grads", Center for Immigration Studies blog, February 27, 2018.

5 See John Miano, "Court Rules American Worker Plaintiffs Have Standing in H-4 EAD Lawsuit", Center for Immigration Studies blog, November 9, 2019.

6 See Daniel Costa and Ron Hira, "H-1B visas and prevailing wage levels", Economic Policy Institute, May 4, 2020.

7 For more on OPT, see the work of David North for the Center for Immigration Studies, here.