When I visited the Hungary-Ukraine border last week, it was much quieter than during the first weeks after the Russian invasion, when thousands of people a day poured out of train cars into the small Hungarian border town of Zahony. But there were still some lessons to be learned.

More than 700,000 Ukrainians have entered Hungary since the February 24 start of the war, of whom some 200,000 remain, according to an embassy source I spoke with this week. Many, of course, moved on to other countries in the European Union. But, as I learned last week, many others have returned to Ukraine.

On the four-hour train ride from Budapest to Zahony, I was seated near a Russian-speaking Ukrainian woman with two obstreperous youngsters and two enormous suitcases. My college Russian has mostly abandoned me, but I was able to ask where she was going and she told me home, to Kiev. With Russian troops having withdrawn from around the capital, and the war focused mainly in the eastern part of the Ukraine, the city is no longer under immediate threat. But when I told her it didn't seem safe, and she simply said "home is better".

When we arrived at the station I saw there were many others headed back as well, more than the number arriving from the east. (Poland, which received the largest number of Ukrainians, is seeing the same return flow.) A Red Cross volunteer in Zahony told me about a Chinese student studying in Kiev who returned recently, saying he couldn't wait any longer because he had final exams to take. And the volunteer said that someone had recently come through who was actually on his way back to Donetsk, the major city in the disputed eastern part of the country. He told the volunteer that while there was still fighting in the villages in the region, the city, firmly under the control of the Russian-backed separatist government, was safe enough for him to return.

An Armenian friend told me that the same kind of thing happened several years ago with Armenians who'd fled Aleppo, the main area of Armenian settlement in Syria, during that country's civil war. Many spent several months in Yerevan, capital of the Armenian republic, where they'd fled for refuge, but went back even though the war was still raging. As he wrote me, "People want to live in their homes…Even though conditions in Syria were bad, they were returning to their homes. They didn't need to pay rent at the very least."

The lesson for U.S. policymakers is that caring for refugees in the region where they've found initial refuge is almost always preferable to resettlement thousands of miles away. The Ukrainian woman in Hungary who decided to return to Kiev had only to pack up and buy a train ticket. Her counterparts who have flown to Mexico, crossed the U.S. border, and gone to join relatives in Sacramento, on the other hand, are unlikely ever to return, and even if they wanted to, it would be a long and expensive ordeal.

As the Center's research has shown, resettling a single refugee in the United States burns through money that could have supported a dozen people in their own region. Whatever funds we spend on refugee protection should be focused almost exclusively on helping people where they are, not assisting them to move permanently across the ocean. Doing so is both less expensive – allowing many more to be helped – and makes it easier for people to return when the emergency is over.

Other observations. The Tisza River marks this section of Hungary's post-World War II border with Ukraine. Although it's not especially wide, it's more "grand" than many stretches of the Rio Grande that I've visited. And it can be dangerous – a local journalist told me that a number of people have drowned trying to swim across it to Hungary. That's not because Hungary prevents the entry of Ukrainians; they've long had visa-free access to the EU for up to 90 days, even before the war. Rather, the victims were military-age men, who are barred from leaving by Ukrainian authorities in case the need arises to press them into service. That underlines one of the most noticeable differences between the recent Ukrainian refugee flow and the 2015 crisis – seven years ago, the vast majority of Syrians (and "Syrians") pouring into Europe were military-age men, while virtually all the Ukrainians are women and children.

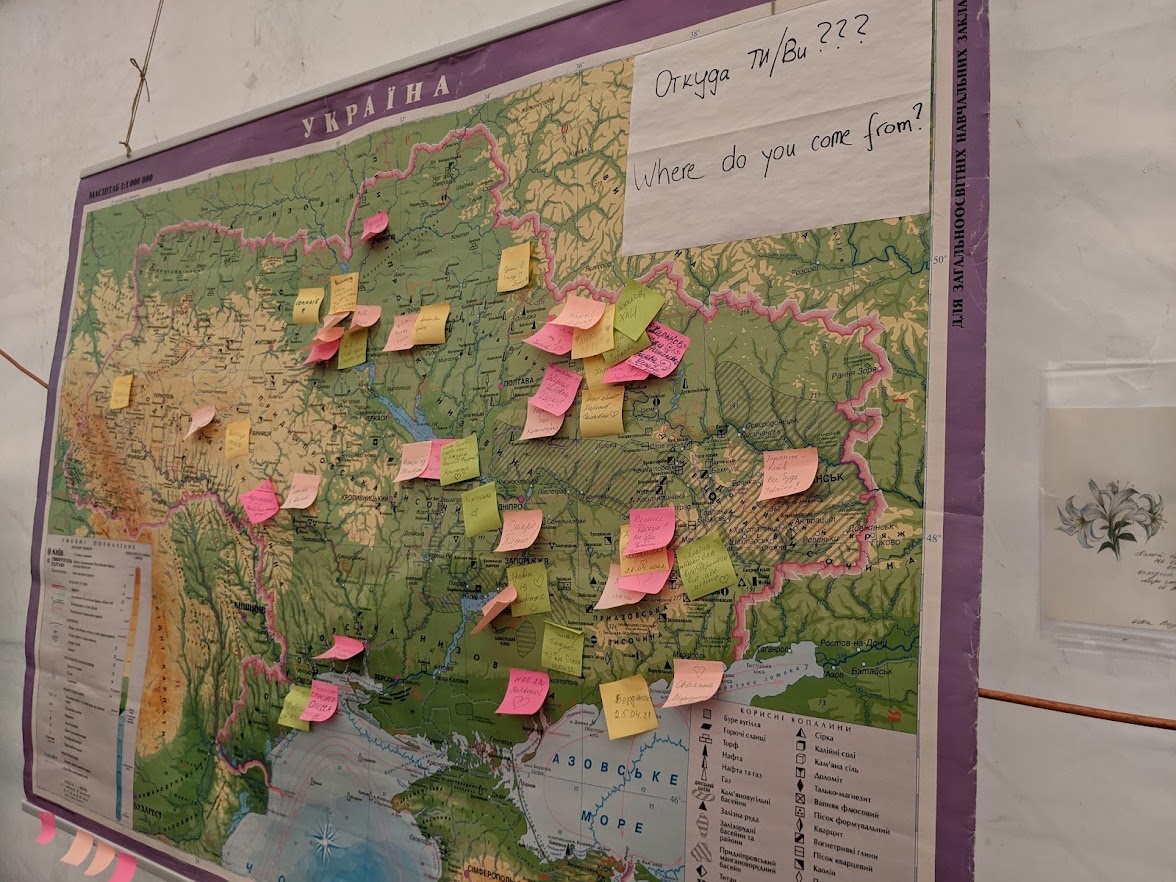

Since the flow is now mainly back into Ukraine, I asked an Italian aid worker in Zahony whether the humanitarian infrastructure there was really still needed. There was a former school converted into a shelter, that sat empty. The tent dining hall, operated by World Central Kitchen (a project of Spanish-born U.S. celebrity chef Jose Andres), was likewise virtually empty at lunchtime. The Jewish Agency setup in the train station had few takers. The Hungarian Red Cross, and the volunteers from the Spanish Red Cross, had little to do. And in general there seemed to be more aid workers than there were Ukrainians to give aid to. But the Italian aid worker told me that, while the number of volunteers has dropped off, they were keeping the infrastructure in place for now, because the war could still flare up and move west, creating new flows of people leaving.

On a lighter note, right near the river was a farm with some of the famous Hungarian Mangalitsa pigs – that have fur. They're also delicious.