Related Publications: Video

The findings of this study indicate that future levels of immigration will have a significant impact on efforts to reduce global CO2 emissions. Immigration to the United States significantly increases world-wide CO2 emissions because it transfers population from lower-polluting parts of the world to the United States, which is a higher-polluting country. On average immigrants increase their emissions four-fold by coming to America.

Among the findings:

- The estimated CO2 emissions of the average immigrant (legal or illegal) in the United States are 18 percent less than those of the average native-born American.

- However, immigrants in the United States produce an estimated four times more CO2 in the United States as they would have in their countries of origin.

- U.S. immigrants produce an estimated 637 million metric tons of CO2 emissions annually — equal to Great Britain and Sweden combined.

- The estimated 637 tons of CO2 U.S. immigrants produce annually is 482 million tons more than they would have produced had they remained in their home countries.

- If the 482 million ton increase in global CO2 emissions caused by immigration to the United States were a separate country, it would rank 10th in the world in emissions.

- The impact of immigration to the United States on global emissions is equal to approximately 5 percent of the increase in annual world-wide CO2 emissions since 1980.

- Of the CO2 emissions caused by immigrants, 83 percent is estimated to come from legal immigrants and 17 percent from illegal immigrants.

- Legal immigrants have a much larger impact because they have higher incomes and resulting emissions, and they are more numerous than illegal immigrants.

- The above figures do not include the impact of children born to immigrants in the United States. If they were included, the impact would be much higher.

- Assuming no change in U.S. immigration policy, 30 million new legal and illegal immigrants are expected to settle in the United States in the next 20 years.

- In recent years, increases in U.S. CO2 emissions have been driven entirely by population increases as per capita emissions have stabilized.

Introduction

The small body of research on immigration’s environmental impact in the United States has tended to focus on the effects of the population growth induced by immigrants and their U.S.-born offspring on the U.S. environment alone.1 In contrast, the present study attempts to quantify the direct contribution of immigrants in the United States to growing U.S. and global carbon dioxide (CO2) emissions. Since American emissions per capita are much higher than almost all of the immigrant-sending countries, immigration to the United States has significant implications for world-wide emissions.

Greenhouse gas (GHG) emissions, the most important of which is CO2 , raise the concentration of these gases in the earth’s atmosphere. Most scientists think this increase is causing average global temperatures to rise. There is concern that warming in turn may trigger far-reaching, long-term effects on the Earth’s climate and biosphere, and consequently, on human civilization.2 Thus, the impact of U.S. immigration on annual CO2 emissions is an important research question.

U.S. Population Growth Drives Increasing CO2 Emissions

The large population and comparative prosperity of the United States are underpinned by the consumption of fossil fuels on a prodigious scale. In one year alone (2006), Americans burned 1.1 billion tons of coal, 7.6 billion barrels of petroleum, and 21.6 trillion cubic feet of natural gas.3

A fundamental consequence of the combustion of coal, oil, and natural gas to generate electricity, run cars, and heat homes is the release of CO2 into the atmosphere.4 Total U.S. emissions of CO2 have been the highest in the world for many years — until just recently. It now appears that in 2006 China surpassed the United States in annual CO2 emissions.5 However, the United States still leads the world’s largest economies in per capita emissions. China’s annual per capita CO2 emissions in 2005 were just four tons, below the global average and only one-fifth of America’s per capita emissions of 20 tons.6

In recent years U.S. per capita CO2 emissions have held steady and the rise in overall U.S. emissions is entirely due to population growth. The link between population and CO2 emissions is shown in a 2002 study that found GHG emissions in the United States from fossil fuel combustion grew by almost 13 percent from 1990 to 2000. Over the same time period, the U.S. population grew by an almost identical amount. This is powerful direct evidence that increases in U.S. CO2 emissions are driven by population increases as per capita emissions have stabilized.7 Adding more people to the United States, at least recently, has meant a proportional increase in emissions.

Comparing U.S. Emissions to Immigrant-Sending Countries

Research by the Center for Immigration Studies, the Pew Hispanic Center, and the Census Bureau shows that new immigration and births to immigrants are the determinate factors in future U.S. population growth. Immigration is now the driving force behind continued U.S. population growth, accounting directly (immigration itself) and indirectly (through births to immigrants) for at least three-quarters of our annual increase of three million residents. The Center for Immigration Studies has projected that if the current level of (legal and illegal) immigration continues, the U.S. population will grow from 300 million in 2007 to 468 million by 2060. Longer-range projections done by the Census Bureau show a U.S. population by 2100 of between 571 million and 1.18 billion using the Bureau’s middle or high range immigration scenario.8 The U.S. population would grow some even without immigration, but there is no question that immigration is the primary reason the U.S. population continues to increase by about three million each year.

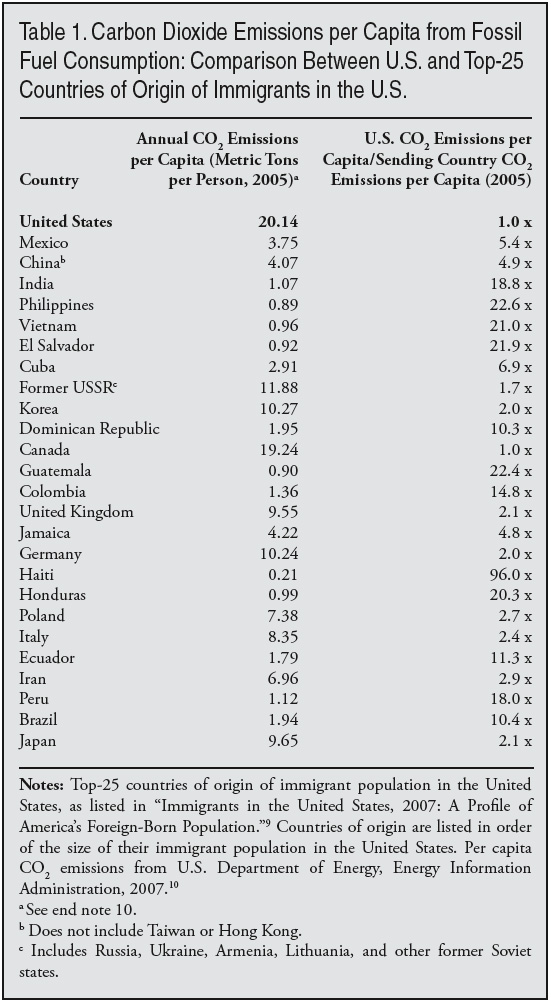

Of course, if immigrants had remained in their home counties they would still have produced some CO2, but as we will see, their output would have been a great deal less because immigration represents a large-scale population transfer from the less consuming, less industrialized, and less CO2 emitting parts of the world to one of the highest consuming, most industrialized, high CO2 emitting parts of the world — the United States. Table 1 compares per capita CO2 emissions in the United States with per capita CO2 emissions in the top-25 immigrant-sending countries.

Table 1 shows extreme variability in per capita CO2 emission rates from country to country. More developed countries of origin — such as Canada, European countries, and Japan — have higher annual per capita CO2 emissions, though with the exception of Canada, even the industrialized countries such as Great Britain, Germany, and Italy all have much lower per capita emissions than the United States. Less-developed countries from Asia and Latin America, which are the primary immigrant-sending counties, have much lower annual per capita CO2 emissions than does the United States. The most extreme example, Haiti, has a per capita CO2 emissions rate of barely more than 1/100 that of the United States. In contrast, Canada’s per capita CO2 emissions are comparable to America’s, which is not surprising considering the similarly large size and advanced level of development of this neighboring North American country.

What is most important about the table is that it shows that almost all of the top immigrant-sending countries to the United States have dramatically lower CO2 emissions per capita. By and large, people who migrate to the United States aspire to improve their material standard of living, and as noted above, this generally entails a higher level of energy consumption and, thus, CO2 emissions. If Table 1 indicated that U.S. CO2 emissions per capita were lower or even the same as the primary immigrant-sending countries, it is likely that immigration to the United States would have little or no effect on world-wide GHG emissions, although total U.S. emissions would still rise dramatically. But, in fact, the United States has much higher per capita CO2 emissions — five times higher — than the world average (20 vs. four metric tons annually). As a result, immigration to the United States has significant implications for world-wide CO2 emissions.

Methodology for Estimating Immigrant CO2 Emissions

One obstacle to estimating annual immigrant and native-born per capita CO2 emission rates is that there are no data that disaggregate rates of these two population cohorts. For that matter, there are also no data that break down per capita CO2 emission rates along other important categories of the United States, such as by urban vs. suburban vs. rural, rich vs. poor, apartment dwellers vs. homeowners, or by ethnic/racial origin. One way around this absence of data is to use annual income as a surrogate for annual CO2 emissions. There is a strong positive correlation between income and CO2 emissions, especially those associated with fossil fuel consumption; that is, an increase in income is associated with an increase, though not necessarily a proportionate increase, in carbon emissions.11 Higher-income Americans simply tend to consume more fossil energy than lower-income Americans, such as by driving instead of taking the bus, longer commutes to larger homes in distant suburbs (large, detached dwellings that take more energy to heat and cool), consuming more goods and services with substantial energy “embodied” in their manufacture production and delivery, taking more airline flights, etc.

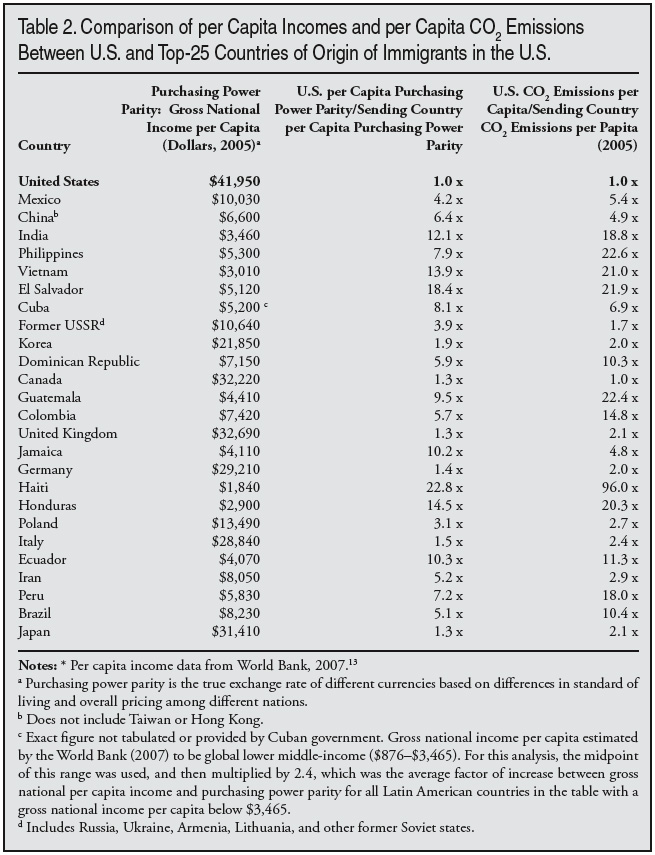

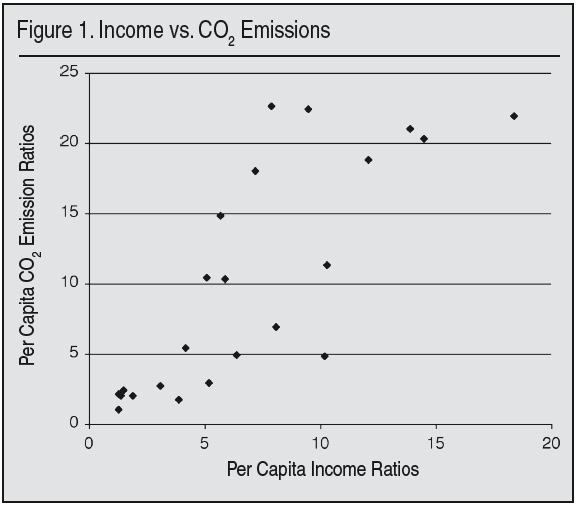

Rather than assuming that all immigrants in the United States have the same annual per capita CO2 emissions as native-born Americans or the average for the United States as a whole, this study postulates a broad correlation between a person’s annual income and his or her annual CO2 emissions. This premise is explored and supported by Table 2, which lists the per capita income and per capita CO2 emissions for each of the 25 countries listed in Table 1. This comparison is useful because it depicts the correlation between per capita income and per capita CO2 emissions from fossil fuel consumption in countries from three continents. Figure 1 is a scatter plot, in which for all countries except Haiti (a statistical outlier), per capita income ratios (X or horizontal axis) are plotted against per capita CO2 emissions ratios (Y or vertical axis). In country after country, as per capita income increases, per capita CO2 emissions increase as well, although not always in lockstep. In this study then, the same relationship is assumed to hold for different populations of immigrants in the United States.

That carbon dioxide emissions are a function of income means that they do not conform to a pattern that environmental economists have observed with other pollutants and “negative externalities.” As national economies’ incomes and Gross Domestic Product (GDP) increase at first, pollution and environmental blight often increase initially but later decrease as incomes continue to grow. When graphed, this relationship takes the form of an inverted or upside-down “U.” Because of its similarity to the pattern of inequality and income first articulated by Nobel Prize-winning economist Simon Kuznets, this pattern of pollution and income has been dubbed the “Environmental Kuznets Curve” (EKC). However, while any number of air and water pollutants and aesthetic/ecological assaults, ranging from rampant deforestation to litter, display this pattern, peak pollution levels occur at different income levels for different pollutants, societies, and time periods.12

The EKC explains societies’ behavior when applied to toxic contaminants that are a visible nuisance and health threat to large numbers of people, such as lead, particulate matter, and sulfur dioxide polluting the air, or raw sewage and industrial effluent defiling water bodies. It is less applicable in the case of pollutants or damage that are hidden, dispersed, or cumulative, like from carbon dioxide emissions or extravagant energy use.

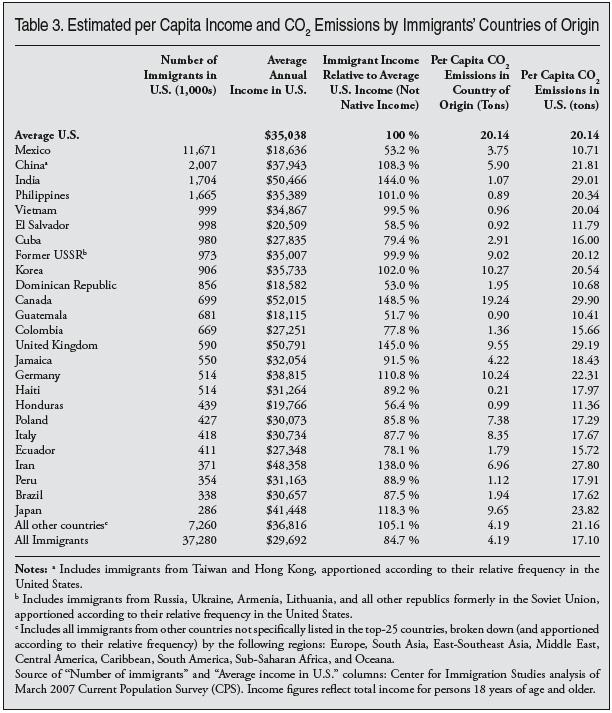

Table 3 uses the average annual per capita incomes of immigrants in the United States to estimate immigrants’ CO2 emissions in 2007. These emissions are compared to per capita emissions in the immigrant’s home country. The first column lists each immigrant home country in descending order, from the country with the highest number of immigrants in the United States (Mexico) to the country in 25th place (Japan). After Japan, an entry for “all other countries” is listed, referring to the more than 100 countries that collectively account for about a fifth of immigrants to U.S. shores.14

The second column in Table 3 lists the number of immigrants in the United States from the country identified in the first column as of 2007.15 The figures in this column do not include children born to immigrants in the United States. The third column displays the average annual income of immigrants in the United States from each country. The fourth column compares this income to the average U.S. income in 2007; a figure above 100 percent (like Canada) means immigrants from the country in question earn more on average than Americans do; a figure below 100 percent (like Honduras) means they have a lower annual income than Americans on average.

The fifth column is per capita CO2 emissions in the immigrants’ countries of origin, while the sixth and final column is the estimated annual per capita CO2 emissions in the United States based on the countries’ average annual incomes. Comparing columns five and six shows the estimated increase in CO2 emissions that occurred by the act of immigrating to and living in the United States. There is clearly great variation in the income and CO2 output of immigrants in the United States. For example, Mexican immigrants are estimated to produce only about half as much CO2 as the average person in the United States. However, this is still more than double the output of the average person in Mexico. Canadian immigrants on the other hand produce almost 50 percent more in CO2 emissions as the average person in the United States.

The final row of Table 3 shows that the average per capita CO2 emissions for all immigrants in the United States was 4.19 metric tons in their sending countries. In the United States, those same immigrants had estimated emissions of 17.1 tons, about four times as high as the average per capita emissions in their countries of origin. Thus, the 37.3 million legal and illegal immigrants now living in the United States in 2007 produced about four times as much CO2 as they would have had they stayed in their home countries.

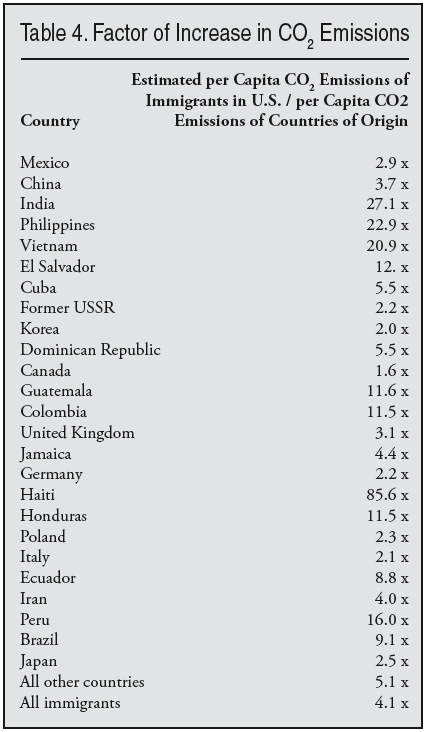

Table 4 shows by how many times immigrants in the United States increased their per capita CO2 emissions relative to average annual per capita emissions in their countries of origin. It is a measure of just how much emissions have increased because of immigration to the United States.

It should be noted that native-born Americans have a slightly higher annual per capita income ($36,008) than the overall average in the United States ($35,038) shown in Table 3. This is because the overall American average includes both native-born and foreign-born Americans’ incomes and the inclusion of immigrants pulls the national average down somewhat. Thus, while Table 3 shows that immigrants on average produce about 85 percent as much CO2 as the average person (immigrant or native-born) living in the United States, compared to just native-born Americans they produce 82 percent as much.

Overall, the more than 37 million immigrants (legal and illegal) living in the United States account for an estimated 637 million metric tons of CO2 emissions each year or 10.7 percent of the U.S. total of 5,957 million metric tons. This is somewhat below their total share of the total population because of their lower average income. Based on estimates developed by the Center for Immigration Studies we estimate that of the 637 million tons of CO2 emitted by immigrants, 83 percent is from legal immigrants and 17 percent is from illegal immigrants. Although about 30 percent of the 37.3 million immigrants living in the United States in March 2007 are estimated to be illegal aliens, they have much lower average incomes than legal immigrants.16 For this reason illegal immigrants produce a smaller share of CO2 emissions than legal immigrants. Illegal immigrants also produce significantly less than native-born Americans.

Impact of U.S. Immigration on Global Emissions

It is instructive to put the estimated output of immigrants into context. The estimated 637 million tons of CO2 emissions generated by immigrants is roughly equal to the annual CO2 emissions of Brazil, Argentina, and Venezuela combined (the three largest emitting countries in South America). It is also equal to the CO2 emissions of Great Britain and Sweden together. If immigrants in the United States were a separate country, they would rank seventh in world CO2 emissions, behind China, the United States, Russia, Japan, India, and Germany.

Of course, if immigrants had stayed in their home countries, they also would have produced greenhouse gases. If the current stock of immigrants in the United States had stayed in their countries of origin rather than migrating to the United States, their estimated annual CO2 emissions would have been only 155 metric tons, assuming these immigrants had the average level of CO2 emissions for a person living in their home countries. This is 482 million tons less than the estimated 637 tons they will produce in the United States. This 482 million ton increase represents the impact of immigration on global emissions. It is equal to approximately 5 percent of the increase in annual world-wide CO2 emissions since 1980.17 If the 482 million ton increase in global CO2 emissions caused by immigration to the United States were a separate country, it would rank 10th in the world. Immigration to the United States thus has significant implications for global greenhouse gas emissions. And it is the total output that matters to CO2 concentrations in the atmosphere, because CO2 emitted anywhere is dispersed everywhere.

It should be noted that Tables 3 and 4 are based on the assumption that immigrants in the United States would have emitted CO2 at rates like the average person in their country of origin if they had remained there. However, in certain cases, particularly Asian countries, this assumption may understate immigrants’ actual emission rates if they had stayed in their home countries because immigrants in the United States from several Asian countries are more educated than is the average person in their home countries. Higher education levels should result in higher incomes and higher CO2 emissions in their home countries. This would mean that the immigrant-induced increase in global emissions would be lower than estimated above. However, there is a strong reason to believe that even if CO2 emissions were higher for immigrants from these countries it would not significantly change the above estimates.

If we assume that immigrants from India would have produced three times the CO2 emissions as the average person in that country and that those from China, the Philippines, and Vietnam would have doubled, it changes the underlying findings only slightly.18 Even making this assumption of much higher emissions in their home countries would still mean that immigrants overall would produce 3.7 times as much CO2 in the United States as they would have in their home counties. This is very similar to the 4.1-fold increase found in Table 4. It must be remembered that highly educated immigrants from Asia account for a modest share of all immigrants in this country. It also should be remembered that immigrants from the largest sending country, Mexico, have very similar education levels to the average person in that country. Moreover, even if their emissions were much higher in their home countries, their output would still be much less than in the United States.

Assuming no change in U.S. immigration policy, 30 million new legal and illegal immigrants are likely to settle in the United States in the next 20 years.19 Primarily because of immigration (new immigrants plus their descendents), the U.S. population is projected to grow by more than 20 percent over this time period, or by at least 60 million.20 Even if per capita CO2 emissions could be reduced by 20 percent in the United States over the next 20 years, total annual U.S. CO2 emissions would remain the same. Total emissions are what matters for the global environment. Efforts to reduce greenhouse gas emissions must include some understanding of how immigration and population growth contribute to greenhouse gas emissions.

Conclusion

Overall, our findings indicate that the average immigrant (legal or illegal) in the United States produces somewhat less CO2 than the average native-born American. However, immigrants in the United States produce about four times more CO2 in the United States as they would have in their countries of origin. The estimated 637 metric tons of CO2 U.S. immigrants produce is 482 million tons more than they would have produced had they remained in their home countries. This 482 million ton increase represents about 5 percent of the increase in annual world-wide CO2 emissions since 1980. These figures do not include the impact of children born to immigrants in the United States. If they were included, the impact would be even higher.

When it comes to dealing with global warming, environmentalists in the United States have generally chosen to adopt what might be described as piecemeal efforts to oppose new sources of fossil fuel-based energy, such as the construction of new coal-fired power plants. They have also supported energy conservation/efficiency (e.g., compact fluorescent light bulbs) and more use of renewable sources like wind and solar energy. But they have assiduously avoided the underlying issue of growing energy demand driven by immigration-fueled population growth. In response to concerns over immigrant-induced population growth, some American environmentalists have even argued that it does not matter where on the Earth people live because the world’s environment is so interconnected. This analysis has shown that when it comes to CO2 emissions it matters a great deal where people live. Per capita CO2 emissions are dramatically higher in the United States than in almost every immigrant-sending country. Large-scale immigration to the United States therefore has enormous implications for world-wide CO2 emissions.

Some may be tempted to see this analysis as “blaming immigrants” for what are really America’s failures. It is certainly reasonable to argue that Americans could do much more to reduce per capita emissions. And it is certainly not our intention to imply that immigrants are particularly responsible for global warming. As we report in this study, immigrants produce somewhat less CO2 on average than native-born Americans. But to simply dismiss the large role that continuing high levels of immigration play in increasing U.S. and world-wide CO2 emissions is not only intellectually dishonest, it is also counter-productive. One must acknowledge a problem before a solution can be found. The effect of immigration is certainly not trivial. If immigrants in the United States were their own country, they would rank seventh in the world in annual CO2 output, ahead of such countries as Canada, France, and Great Britain.

Unless there is a change in immigration policy, 30 million (legal and illegal) immigrants are likely to settle in the United States over the next 20 years. One can still argue for high levels of immigration for any number of reasons. However, one cannot make the argument for high immigration without at least understanding what it means for global efforts to reduce the emission of greenhouse gases.

Some involved in the global warming issue have recognized immigration’s importance. Chief U.S. climate negotiator and special representative for the United States, Harlan Watson, has acknowledged high immigration to the United States is thwarting efforts to slow its rising GHG emissions. “It’s simple arithmetic,” said Watson. “If you look at mid-century, Europe will be at 1990 levels of population while ours will be nearing 60 percent above 1990 levels. So population does matter.”21 This research confirms Watson’s observation.

Endnotes

1 R. Beck, L. Kolankiewicz, and S.A. Camarota.2003. Outsmarting Smart Growth: Population Growth, Immigration, and the Problem of Sprawl. Washington, DC: Center for Immigration Studies. Available at http://www.cis.org/sites/cis.org/files/articles/2003/sprawl.html.

2 Committee on the Science of Climate Change, National Research Council, National Academy of Sciences. 2001. Climate Change Science: An Analysis of Some Key Questions. National Academies Press: Washington, DC; Intergovernmental Panel on Climate Change (IPCC). 2007. Climate Change 2007: The Physical Science Basis — Summary for Policymakers. Contribution of Working Group I to the Fourth Assessment Report of the Intergovernmental Panel on Climate Change. Cambridge University Press: Cambridge, UK.

3 Coal: Fred Freme, Energy Information Administration (EIA). 2007. U.S. Coal Supply and Demand — 2006 Review. April. Accessed online at: http://www.eia.doe.gov/cneaf/coal/page/special/feature.html; Petroleum: EIA. 2007. Petroleum Products Consumption. Accessed online at: http://www.eia.doe.gov/neic/infosheets/petroleumproductsconsumption.html; Natural gas: EIA. 2008. Natural gas total consumption MMcf. Accessed online at: http://tonto.eia.doe.gov/dnav/ng/hist/n9140us2A.htm.

4 Pilot projects to capture and sequester carbon dioxide — thus circumventing its release to the atmosphere — are now underway, but whether “carbon capture and sequestration” on a huge scale will ever prove technically feasible and economically viable is highly uncertain at this juncture.

5 Bloomberg News. 2007. “China overtakes U.S. in greenhouse gas emissions.” International Herald Tribune. June 20. Accessed 3-19-08 online at: http://www.iht.com/articles/2007/06/20/business/emit.php .

6 U.S. Department of Energy, Energy Information Administration. 2007. International Energy Annual 2005. Table H1cco2: World Per Capita Carbon Dioxide Emissions from the Consumption and Flaring of Fossil Fuels, 1980-2005. Posted October 1, 2007. Accessed 2-5-08 online at: http://www.eia.doe.gov/pub/international/iealf/tableh1cco2.xls

7 For more discussion of this issue see L. Kolankiewicz. 2002. Population Growth — The Neglected Dimension of America’s Persistent Energy/Environmental Problems. October. NumbersUSA Education and Research Foundation. Available online at http://www.numbersusa.com/about/books.html.

8 The Center for Immigration Studies projections are in 100 Million More: Projecting the Impact of Immigration On the U.S. Population, 2007 to 2060, which can be found at: www.cis.org/sites/cis.org/files/articles/2007/back707.html. A recent Pew Hispanic Center report estimated that 82 percent of population growth between 2005 and 2050 will be from immigrants and their descendents. The report, U.S. Population Projections: 2005-2050, can be found at http://pewhispanic.org/files/reports/85.pdf. The last time the Census Bureau did population projections under different immigration scenarios was in 2000. Table F of the methodology section of that report shows the impact of different immigration scenarios on U.S. population size. See “Methodology and Assumptions for the Population Projections of the United States: 1999 to 2100”: U.S. Census Bureau, Population Division Working Paper No. 38. Issued January 13, 2000. Available at http://www.census.gov/population/www/projections/natproj.html.

9 S.A. Camarota. 2007. “Immigrants in the United States, 2007: A Profile of America’s Foreign-Born Population.” Washington, DC: Center for Immigration Studies Backgrounder. November.

10 Energy Information Administration. 2007. International Energy Annual 2005. Table H1cco2: World Per Capita Carbon Dioxide Emissions from the Consumption and Flaring of Fossil Fuels, 1980-2005. Posted October 1, 2007. Accessed 2-5-08 online at: http://www.eia.doe.gov/pub/international/iealf/tableh1cco2.xls.

11 U.S. Department of Energy, Energy Information Administration. 2008. Emissions of Greenhouse Gases Report. Report No.: DOE/EIA-0573(2006). http://www.eia.doe.gov/oiaf/1605/ggrpt/carbon.html, released November 28, 2007: “In the longer run, residential [carbon] emissions are affected by population growth and income;” Proceedings of the National Academy of Sciences. 2007. Vol. 104, No. 24. Published online May 22, 2007. http://www.pnas.org/cgi/content/full/104/24/10288: “Nearly constant or slightly increasing trends in the carbon intensity of energy [emissions/energy] have been recently observed in both developed and developing regions;” Panel on Policy Implications of Greenhouse Warming, National Academy of Sciences, National Academy of Engineering, Institute of Medicine, Committee on Science, Engineering, and Public Policy. 1992. Policy Implications of Greenhouse Warming: Mitigation, Adaptation, and the Science Base. National Academies Press: Washington, DC. From Appendix N, Population Growth and Greenhouse Gas Emissions: “Annual CO2 emissions are calculated from population and income projections. It is assumed that CO2 emissions increase proportionately with population for all income levels. For low income levels (i.e., multiples below five), it is assumed that CO2 emissions additionally increase proportionately with per capita income growth. For higher incomes, CO2 emissions increase less than proportionately with per capita income growth (i.e., at 0.8 for income multiples between five and 10, 0.7 for multiples between 10 and 30, and 0.6 for higher multiples).”

12 New Palgrave Dictionary of Economics, 2nd edition. Accessed May 1, 2008 at: http://www9.georgetown.edu/faculty/aml6/pdfs&zips/PalgraveEKC.pdf .

13 World Bank. 2007. World Development Indicators 2007. Table 1.1: Size of the economy. Accessed 02-04-08 online at http://www.siteresources.worldbank.org/DATASTATISTICS/RESOURCES/table1_1....

14 Includes all immigrants from other countries not specifically listed in the top-25 countries, broken down (and apportioned according to their relative frequency) by the following regions: Europe, South Asia, East-Southeast Asia, Middle East, Central America, Caribbean, South America, Sub-Saharan Africa, and Oceana.

15 The figures are from the March 2007 Current Population Survey collected by the U.S. Census Bureau. The numbers are for all persons from each country. The income figures are based on the total income of persons 18 and older. Most researchers think about 90 percent of illegal immigrants respond to the Survey. Thus the figures in the table represent the total income of immigrants and natives.

16 Based on the March 2007 Current Population Survey, which is the primary data source used in this study for immigrants, we estimate that the average annual income of illegal immigrants over age 18 was $17,497. We also estimate that the average annual income for legal immigrants 18 and older was $34,473. In effect, illegal immigrants account for 18 percent of the aggregate income earned by all immigrants and legal immigrants account for 82 percent of the aggregate income. For more discussion of the characteristics of the illegal immigrants see “Immigrants in the United States 2007: A Profile of America’s Foreign-born Population,” available at www.cis.org/sites/cis.org/files/articles/2007/back1007.html.

17 The March 2007 Current Population Survey shows that the vast majority of immigrants in the United States arrived in 1980 or later. Global CO2 emissions from fuel consumption and flaring were 18,331 million metric tons in 1980. Global emissions in 2005 were 28,193 million metric tons. Thus, annual world output of CO2 increased by 9,862 million metric tons during this quarter-century, or 54 percent. The estimated increase in immigrants’ CO2 emissions in the United States over what they would have been in their countries of origin is 482 million metric tons.

18 Iran is another country whose immigrants in the United States are much more educated than the average person in Iran. We do not adjust their assumed output for the following reason: Iran has relatively high per capita emissions for a developing country mainly because of the flaring of natural gas associated with its oil industry. However, much of the oil Iran produces is consumed outside of Iran. Thus the actual per capita output actually attributable to fossil fuel consumption by the people of Iran is less than is implied by their per capita numbers found in Tables 3 and 4. So it makes little sense to adjust their figures upward in the way we do India, China, Vietnam, and the Philippines. Of course, this means that immigration from Iran to the United States represents an even larger impact on world-wide CO2 emissions because emissions caused by the consumption of the people of that country are actually lower than implied by the tables.

19 In recent years the Current Population Survey and the American Community Survey, both collected by the Census Bureau, have indicated that about 1.5 million new immigrants settle in the country each year. There is some undercount in these surveys of recently arrived immigrants, and therefore it is more likely that 1.6 million new immigrants arrive each year. The Pew Hispanic Center assumes a 5.2 percent undercount in the overall immigrant population. This is based research by Passel, Van Hook, and Bean as part of a Census Bureau contract through Sabre Systems. But even assuming only 1.5 million new arrivals would still place the total number of new arrivals over 20 years at 30 million — 1.5 x 30. It is also worth noting that immigration to the United States, both legal and illegal, has been steadily increasing for 40 years. If that long-standing trend continues, then significantly more than 30 million new immigrants will arrive in the United States, assuming no change in policy.

20 Projections by the Census Bureau, the Center for Immigration Studies, and the Pew Hispanic Center all show that the U.S. population grows by about 1 percent each year. Thus, over a 20 year period, population growth is very roughly 20 percent. The Center for Immigration Studies projections can be found at, www.cis.org/sites/cis.org/files/articles/2007/back707.html. The Pew Hispanic Center estimates can be found at: http://pewhispanic.org/files/reports/85.pdf. The Census projections can be found at: http://www.census.gov/ipc/www/usinterimproj/.

21 Doyle, Allister. Aug 30, 2007. Reuters News Service. http://africa.reuters.com/wire/news/usnL30472039.html .