Alex Nowrasteh at the Cato Institute and Philip Wolgin at the Center for American Progress (CAP) each comment on, but don't really try to refute, a new report that I co-authored on the lack of a shortage of STEM workers. The American Immigration Lawyers Association's Paul McDaniel also comments on the report at the association's American Immigration Council website. Like Nowrasteh and Wolgin, McDaniel doesn't really try to refute the report. He cites Cato and CAP and also repeat a number of the points from our report.

Let me address Cato's blog first because both Wolgin and McDaniel partly rely on Cato. Nowrasteh and Cato have an ideological commitment to open borders, which leads them to argue things that often make little or no sense. For example, in one report they tried to argue that immigrant welfare use was not high because poor immigrants use welfare at rates similar to poor natives. Of course, the share of immigrants and their young children who are poor is 70 percent higher than natives; and immigrant households do in fact use welfare at significantly higher rates than natives. Their argument on welfare is like saying that a basketball team comprised of players who are five feet tall should be considered great because they are as good as any other team of the same height.

On STEM, Nowrasteh ignores not just our report, but studies by the Economic Policy Institute (EPI), the Rand Corporation, the Urban Institute, the National Research Council and an important new book by a top scholar in the field, all of which show no evidence that science, technology, engineering, and math workers are in short supply. There are about 2.5 times as many people in the country with STEM degrees as there are STEM jobs. To make his case that there is a shortage, Nowrasteh cites wage data that almost exactly match what is in our report. They show that wages for STEM workers have increased between 2 percent (computers) and 5.9 percent (engineering plus architecture) over the 11 years from 2001 to 2011. This means that Nowrasteh thinks that annual growth in wages of between two-tenths and five-tenths of one percent a year for 11 years is evidence of a tight labor market. This is absurd on its face.

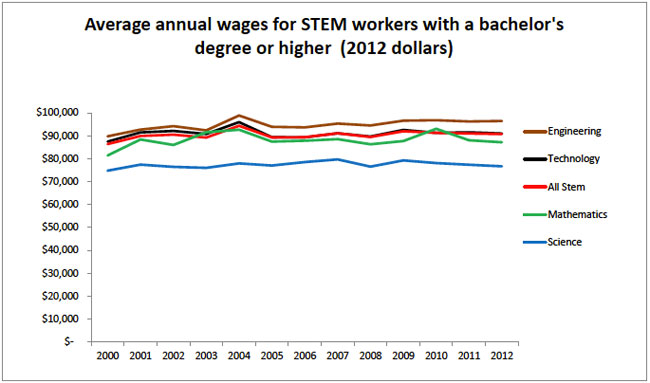

Why would he take such a view? He argues that other workers have done worse, which in his mind somehow means that STEM workers are experiencing big increases and therefore they are in short supply. What it really means is that demand for labor in general is weak — for STEM workers and non-STEM workers alike. Reader are free to judge for themselves; the figure below shows annual wages for STEM workers from 2000 to 2012 in inflation-adjusted dollars from our new report. (More detailed information can be found in Tables A7 and A8 of the report.) As I said at the outset, Cato's ideology causes them to write and say things that defy economic principles and common sense.

The Center for American Progress cites Nowrasteh to make the same basic points. CAP has been described as race-baiters and unfortunately this does describe Philip Wolgin's discussion of our report. Like others at CAP, rather than engage in intelligent discourse, he calls anyone who disagrees with his position on immigration "nativist" and "anti-immigrant." One point that Wolgin makes that Nowrasteh does not is that many people leave STEM jobs as they age. Of course, many people change jobs and fields in their lifetime, not just those with STEM degrees. He does not seem to understand that one reason people leave STEM is the relatively low wages. Equally important, only about one-third of Americans graduating each year with new STEM degrees actually get STEM jobs.

Paul McDaniel, writing for the immigration lawyers, cites Cato and CAP. He also argues that other research shows STEM workers are in short supply. The research he cites is supportive of STEM immigration, but does not really make the case that STEM workers are in short supply. He also ignores all the research cited above showing that the supply of STEM workers is more than adequate. Oddly, he then makes many of the same points that are in our report. For example, he argues that unemployment is low in STEM occupations, which we show in Tables 1 and A6 of our report. But this does not change the fact that there are a huge number of STEM degree holders not working in STEM jobs, immigrant and native. He also argues that native-born STEM workers employed outside of STEM earn wages similar to those in STEM jobs, which we also show in Figures 5 and 6 of our report. He does not seem to realize that if STEM jobs do not pay especially well, then it is an indication that STEM labor is not in short supply.

He concludes by arguing that there are geographic areas where the supply of STEM workers is insufficient. His assumption is that it is better to bring in foreign workers than to encourage employers to pay more and recruit American workers from other parts of the country. Employers and the immigration lawyers they hire may certainly like this idea. But it is not at all clear that this is in the interest of the American people. We conclude our STEM report with the following observation:

There may be a specific geographic area or a highly specialized field in which demand really is outstripping supply. However, it makes little sense to allow public policy to be driven by very narrow interests. If there is some special need in a highly technical field then perhaps a narrowly focused immigration program is necessary. But overall, the data indicate that the supply of STEM workers vastly exceeds the number of STEM jobs, and there has been only modest wage growth in these professions. This reality should inform and shape public policy moving forward.