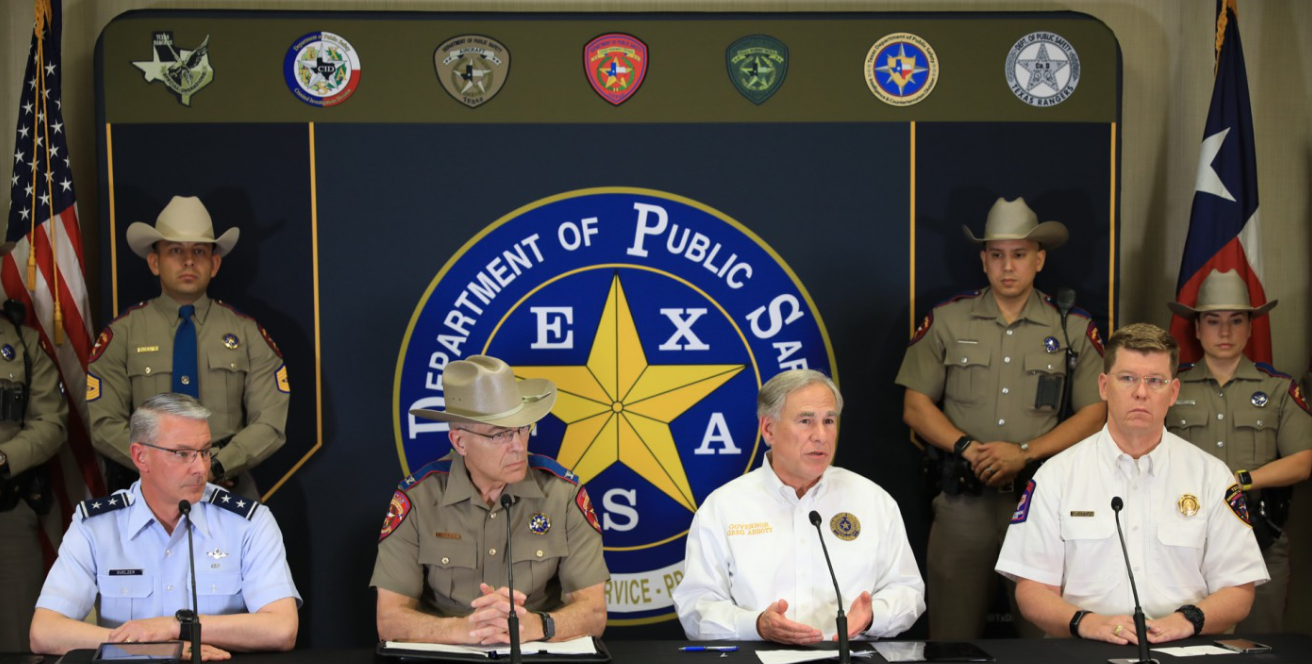

On July 7, Texas Governor Greg Abbott (R) issued an executive order allowing Texas state troopers and state National Guard soldiers to apprehend illegal migrants and return them to the border. It is a powerful move borne of frustration with an administration that has no interest in deterring illegal entrants, but it also reveals the limits of state power — and the importance of a recent Fifth Circuit order in Texas v. United States. Texas gave up most of its rights to enforce the immigration laws when it joined the union, and the Biden administration must now live up to its end of the constitutional bargain.

The Texas Border Tsunami and the Governor’s Response. Texas is uniquely vulnerable to an insecure border. The states’ border with Mexico is 1,254 miles, or more than 64 percent of the total Southwest border (1,954 miles). There are 20 Border Patrol sectors nationwide (including in Puerto Rico), nine are on the Southwest border, and five cover Texas.

It should also be noted that much of that Texas border is further south — and thus much closer to Central America — than its sister border states of New Mexico, Arizona, and California. McAllen, Texas, in the heart of the Rio Grande Valley (RGV) sits at a latitude of 26.2 degrees north, much further south than, say, the border town of San Ysidro, Calif. (latitude 33.255 north).

If you weren’t a Boy Scout or aren’t a sailor, and lines of latitude (running east and west) and longitude (running north and south) are meaningless, consider the fact that McAllen is slightly closer in latitude to Mexico City (19.43 degrees north) than to San Ysidro — one of the southernmost cities in California.

As “other than Mexican” (OTM) migrants are increasingly a larger percentage of illegal entrants, that proximity makes the trip to Texas in general and the RGV in particular much more attractive to increasing numbers of foreign nationals seeking illegal entry and to their smugglers.

Through the end of May, Border Patrol agents at the Southwest border have apprehended 1.44 million illegal migrants in FY 2022; nearly 895,000 — 62 percent of the total — were in the five Texas sectors, and nearly 614,000 of those (42.6 percent of the border-wide total) were in just two Texas sectors — RGV and Del Rio.

Since President Biden took office and ditched nearly every border policy implemented by Donald Trump that had brought a measure of operational control to the U.S.-Mexico line, Abbott and Texas have stepped in to fill the enforcement void.

Most significantly, the governor launched Operation Lone Star, which surged troopers and the National Guard to the Rio Grande. In late April, the governor’s office announced that those officials had nabbed 239,849 migrants, made 14,364 criminal arrests, lodged 11,666 felony charges, seized more than 4,710 weapons and almost $37 million in currency, and stopped the shipment of more than 342 million lethal doses of fentanyl throughout the state.

It is understandable that Republican Abbott and Democratic President Joe Biden don’t see eye-to-eye on the parlous state of the Southwest border, but more than politics is at play here. I have seen up close the deleterious effects a flood of migrants, some of the nearly 1.05 million illegal entrants DHS cut loose into the United States between the start of the Biden administration and the end of May, have had on communities along the Mexican border.

That does not even count the human carnage. The 50-plus migrants found dead in an abandoned trailer in southwest San Antonio are just a small portion of the border deaths this fiscal year, on top of an estimated 650 in FY 2021. At least the San Antonio deaths garnered national attention.

Issues Facing State Efforts. Not surprisingly, Operation Lone Star has its detractors, with some contending that the state is inflating its numbers, and others asserting extended border deployments are taking a toll on the National Guard. DOJ is allegedly investigating civil rights violations under Title VI of the Civil Rights Act of 1964, a law that bars discrimination based on race, color, or national origin in activities or programs receiving federal funding.

I was embedded with the troopers in August, and I identified one problem facing Lone Star: Texas can arrest illegal migrants and charge them on state grounds for trespassing, theft, drug trafficking, or vandalism, but it cannot deport them. Only the federal government can do that.

Texas and the other 49 states surrendered various rights and authorities when they entered the Union, and nowhere is this truer than in their ability to enforce the immigration laws. Immigration is the ultimate federal authority and in 2012 the Supreme Court held that the states have no power to enforce the immigration laws themselves.

That’s why Texas has standing in cases like Texas. It’s also why Abbott’s order ends on the northern banks of the Rio Grande. The governor cannot force migrants to go back across the river, nor can he force the Mexican government to take those migrants back (especially if they are OTMs).

In Texas, the Fifth Circuit held that DHS Secretary Alejandro Mayorkas cannot direct ICE officers to ignore the mandates in the Immigration and Nationality Act (INA) to arrest, detain, and remove criminal aliens, nor can he restrict their wholesale statutory discretion to take other immigration enforcement actions.

Nowhere are the problems with the Biden’s immigration scheme clearer than in Mayorkas’s own enforcement guidelines memo, which sets out the secretary’s non-enforcement policies and which was at issue in Texas. While the executive has a lot of power when it comes to immigration, it must follow Congress’ directives in exercising that power.

As the Supreme Court has explained:

Policies pertaining to the entry of aliens and their right to remain here are peculiarly concerned with the political conduct of government. In the enforcement of these policies, the Executive Branch of the Government must respect the procedural safeguards of due process. But that the formulation of these policies is entrusted exclusively to Congress has become about as firmly imbedded in the legislative and judicial tissues of our body politic as any aspect of our government. [Emphasis added.]

In the INA, Congress identified classes of inadmissible and deportable aliens, and directed DHS in mandatory terms to remove all aliens under final orders from the United States. In defiance of those mandates, however, on page 2 of his guidance memo, Mayorkas states: “The fact an individual is a removable noncitizen therefore should not alone be the basis of an enforcement action against them.”

Lest you think that is nothing more than Mayorkas’s opinion, consider the fact that a “Considerations” memo accompanying the Mayorkas guidance — intended to explain and implement that guidance — stated that “the new guidelines will require the workforce to engage in an assessment of each individual case and make a case-by-case assessment as to whether the individual poses a public safety threat, guided by a consideration of aggravating and mitigating factors.” (Emphasis added.)

The problem is Congress never told ICE officers to consider any such “aggravating and mitigating factors”, aside from whether the alien was removable, and the Fifth Circuit specifically found that forcing officers to consider those factors wastes the limited resources the Mayorkas guidance purports to conserve.

The Limits of State Immigration Power Under the U.S. Constitution. In much the same way that Ukraine surrendered its nuclear weapons in 1994 under the Budapest Memorandum in exchange for a guarantee by the United States, United Kingdom, and Russia not to use force against it, Texas signed away its right to enforce the immigration laws when it joined the federal union in December 1845, in exchange for a guarantee of enforcement by the U.S. government.

Abbott’s order allowing his officers to drop illegal migrants off at the U.S. side of the border reflects the constitutional limits on the state’s power to protect itself from the adverse impacts of immigration. The Fifth Circuit’s order in Texas, on the other hand, is grounded in the laws forcing the U.S. government to live up to its end of the federal immigration bargain. At the border, the Biden administration needs to understand: A deal’s a deal, especially when that deal is inked into law.