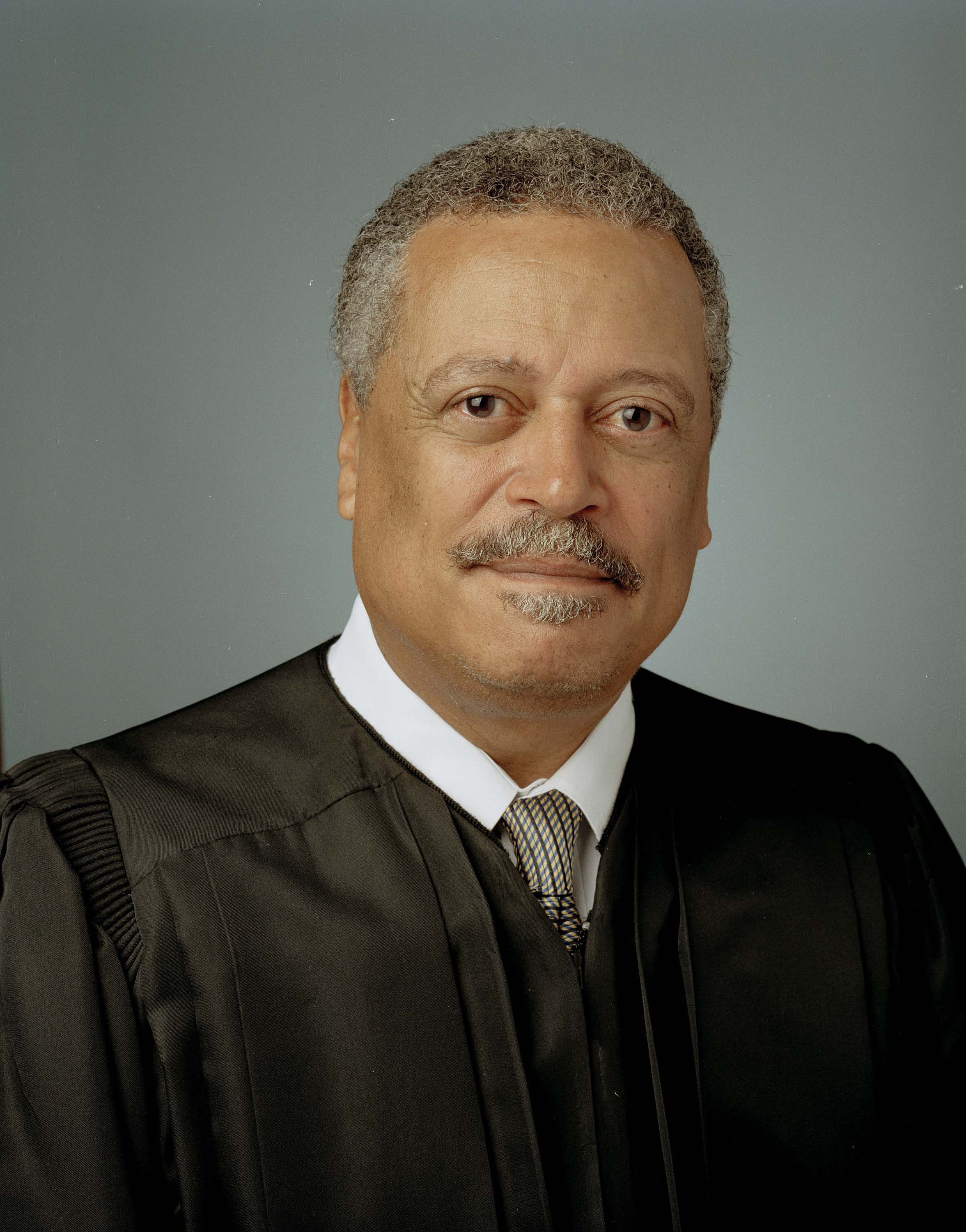

On Monday, Judge Emmet G. Sullivan of the U.S. District Court for the District of Columbia issued an order in Grace v. Whitaker, permanently enjoining certain credible-fear policies that were contained in then-Attorney General (AG) Jeff Sessions' decision in Matter of A-B- (which I detailed in a June 13, 2018, post), as well as in a policy memorandum issued by U.S. Citizenship and Immigration Services (USCIS) implementing that decision (which I analyzed in a July 2018 post). This decision, which was a result that Congress never intended when it explicitly limited the jurisdiction of courts in expedited-removal cases, will have far-reaching consequences beyond what I believe even Judge Sullivan ever likely envisioned.

First, it is important to note that Matter of A-B- did not involve credible fear at all, at least not directly. As I explained in a June 2018 post:

In Matter of A-B-, the attorney general returned to fundamental issues of asylum law, including what "persecution" is, how a "particular social group" is defined, and the requirement that there be a "nexus" between the social group identified and the persecution that was purportedly inflicted or is feared.

At issue there was a claim for asylum by a Salvadoran national who had entered the United States illegally. She asserted that she was eligible for asylum because she had been persecuted on account of her membership in what she described as the particular social group of "'El Salvadoran women who were unable to leave domestic relationships because they have children in common with their partners."

The immigration judge who heard that application denied it in December 2015 on four separate grounds: First, that the applicant was not credible because of discrepancies and omissions in her testimony. Second, that the proposed group did not qualify as a "particular social group" for purposes of section 101(a)(42)(A) of the INA. Third, that even if that group did satisfy that standard, the applicant failed to show "that her membership in that social group was a central reason for her persecution." Fourth, that the applicant had failed to show that the Salvadoran government "was unable or unwilling to help her."

The [Board of Immigration Appeals (BIA)] reversed that decision in December 2016. First, the BIA concluded that the immigration judge's credibility determination was "clearly erroneous". Second, the BIA found that the particular social group in question was "substantially similar" to a group recognized by the BIA as meriting asylum in Matter of A-R-C-G-, specifically "married women in Guatemala who were unable to leave their relationship". In addition, the BIA held "the immigration judge clearly erred in finding that the respondent could leave her ex-husband," and further, that the applicant "established that her ex-husband persecuted her because of her status as a Salvadoran woman unable to leave her domestic relationship." The BIA finally concluded "the El Salvadoran government was unwilling or unable to protect" the applicant.

The attorney general vacated that decision, and remanded it to the immigration judge.

See? No credible fear. The alien in that case was a respondent in removal proceedings who was applying for asylum. Credible fear is an associated, but different process that can lead to the filing of an asylum application in a removal proceeding, but not always. In an April 2017 Backgrounder captioned "Fraud in the 'Credible Fear' Process, Threats to the Integrity of the Asylum System", I explained the expedited-removal and credible-fear processes:

A credible fear request is a precondition to filing a defensive asylum application for an alien in expedited removal proceedings under section 235(b) of the Immigration and Nationality Act (INA). That section of the INA allows immigration officers — rather than judges — to order the deportation of aliens who have failed to establish that they have been in the United States continuously for two years and who have been charged with inadmissibility under section 212(a)(6)(c) (fraud or misrepresentation) and/or section 212(a)(7) (no documentation) of the INA. DHS has expanded its use of expedited removal over the years.

The most common instance in which DHS uses expedited removal is when it apprehends (1) an alien seeking admission without a proper entry document at a port of entry; or (2) an alien who is attempting to enter or who has entered illegally along the border. If the alien asserts a fear of persecution, the arresting officer will refer the alien to an asylum officer for a "credible fear interview". If the asylum officer determines that the alien has a credible fear, the alien is placed in removal proceedings before an immigration judge, where the alien can file his or her application for asylum.

Under section 235(b)(1)(B)(v) of the INA, "the term 'credible fear of persecution' means that there is a significant possibility, taking into account the credibility of the statements made by the alien in support of the alien's claim and such other facts as are known to the officer, that the alien could establish eligibility for asylum under section 208."

Credible-fear determinations are made by asylum officers within U.S. Citizenship and Immigration Services (USCIS), not immigration judges within the Department of Justice (DOJ). Because Matter of A-B- addresses the standards for the granting of asylum, and because the credible-fear standard is based on the possibility that an alien in expedited removal proceedings could be eligible for asylum, Matter of A-B- has an effect on credible fear, but not a direct one.

How is it possible that the AG in DOJ could make a decision that is binding on an asylum officer in USCIS? Section 103(a)(1) of the Immigration and Nationality Act (INA) delineates between the powers of the secretary of Homeland Security and the AG as those powers relate to immigration:

The Secretary of Homeland Security shall be charged with the administration and enforcement of this chapter and all other laws relating to the immigration and naturalization of aliens, except insofar as this chapter or such laws relate to the powers, functions, and duties conferred upon the President, Attorney General, the Secretary of State, the officers of the Department of State, or diplomatic or consular officers: Provided, however, That determination and ruling by the Attorney General with respect to all questions of law shall be controlling. [Emphasis added.]

So, Congress makes the immigration laws, the AG interprets those laws, and the Secretary of Homeland Security applies those laws, the latter two generally through subordinates. Except for when judges do all three, as Judge Sullivan did in Grace.

With respect to subordinates, the AG usually leaves it up to the Board of Immigration Appeals (BIA) to make determinations and rulings with respect to questions of law, including interpretation of the asylum statutes. Specifically, under 8 C.F.R. § 1003.1(g):

Decisions as precedents. Except as Board decisions may be modified or overruled by the Board or the Attorney General, decisions of the Board, and decisions of the Attorney General, shall be binding on all officers and employees of the Department of Homeland Security or immigration judges in the administration of the immigration laws of the United States. By majority vote of the permanent Board members, selected decisions of the Board rendered by a three-member panel or by the Board en banc may be designated to serve as precedents in all proceedings involving the same issue or issues. Selected decisions designated by the Board, decisions of the Attorney General, and decisions of the Secretary of Homeland Security to the extent authorized in paragraph (i) of this section, shall serve as precedents in all proceedings involving the same issue or issues.

The AG, however, has not delegated all of his authority under section 103 of the INA to the BIA. Rather, under 8 C.F.R. § 1003.1(h), the AG, using his certification authority, may direct the BIA to refer cases to him for review, which he did in Matter of A-B-.

Which brings us back to Judge Sullivan's opinion in Grace. In most cases, the U.S. District Court for the District of Columbia does not have jurisdiction over immigration cases. That is because pursuant to section 242(b)(2) of the INA, jurisdiction over petitions for review from BIA decisions are to be "filed with the court of appeals for the judicial circuit in which the immigration judge completed the proceedings," and there are no immigration courts in the District of Columbia. There are a few specific exceptions, however, where the U.S. District Court for the District of Columbia has sole authority to make decisions. One of those exceptions relates to expedited removal.

Specifically, section 242(a)(2)(A) of the INA states:

REVIEW RELATING TO SECTION 235(b)(1) .-Notwithstanding any other provision of law (statutory or nonstatutory), including section 2241 of title 28, United States Code, or any other habeas corpus provision, and sections 1361 and 1651 of such title, no court shall have jurisdiction to review-

(i) except as provided in subsection (e), any individual determination or to entertain any other cause or claim arising from or relating to the implementation or operation of an order of removal pursuant to [the expedited-removal procedures in] section 235(b)(1),

(ii) except as provided in subsection (e), a decision by the Attorney General to invoke the provisions of such section,

(iii) the application of such section to individual aliens, including the determination made under section 235(b)(1)(B), or

(iv) except as provided in subsection (e), procedures and policies adopted by the Attorney General to implement the provisions of section 235(b)(1) .

The provision referenced in section 242(a)(2)(A)(iii) of the INA above, section 235(b)(1)(B) of the INA, is the credible-fear provision. If that is the case, then section 242(e) of the INA must be pretty broad, right, if it gave Judge Sullivan of the U.S. District Court for the District of Columbia jurisdiction over the AG's decision in Matter of A-B-, such that he could enjoin portions of that decision? Actually, no. In fact, that provision is extremely restrictive:

Judicial Review of Orders Under Section 235(b)(1) .-

(1) Limitations on relief.-Without regard to the nature of the action or claim and without regard to the identity of the party or parties bringing the action, no court may-

(A) enter declaratory, injunctive, or other equitable relief in any action pertaining to an order to exclude an alien in accordance with section 235(b)(1) except as specifically authorized in a subsequent paragraph of this subsection, or

(B) certify a class under Rule 23 of the Federal Rules of Civil Procedure in any action for which judicial review is authorized under a subsequent paragraph of this subsection.

(2) Habeas corpus proceedings.-Judicial review of any determination made under section 235(b)(1) is available in habeas corpus proceedings, but shall be limited to determinations of-

(A) whether the petitioner is an alien,

(B) whether the petitioner was ordered removed under such section, and

(C) whether the petitioner can prove by a preponderance of the evidence that the petitioner is an alien lawfully admitted for permanent residence, has been admitted as a refugee under section 207, or has been granted asylum under section 208, such status not having been terminated, and is entitled to such further inquiry as prescribed by the Attorney General pursuant to section 235(b)(1)(C) .

(3) Challenges on validity of the system.-

(A) In general.-Judicial review of determinations under section 235(b) and its implementation is available in an action instituted in the United States District Court for the District of Columbia, but shall be limited to determinations of-

(i) whether such section, or any regulation issued to implement such section, is constitutional; or

(ii) whether such a regulation, or a written policy directive, written policy guideline, or written procedure issued by or under the authority of the Attorney General to implement such section, is not consistent with applicable provisions of this title or is otherwise in violation of law.

(B) Deadlines for bringing actions.-Any action instituted under this paragraph must be filed no later than 60 days after the date the challenged section, regulation, directive, guideline, or procedure described in clause (i) or (ii) of subparagraph (A) is first implemented.

(C) Notice of appeal.-A notice of appeal of an order issued by the District Court under this paragraph may be filed not later than 30 days after the date of issuance of such order.

(D) Expeditious consideration of cases.-It shall be the duty of the District Court, the Court of Appeals, and the Supreme Court of the United States to advance on the docket and to expedite to the greatest possible extent the disposition of any case considered under this paragraph.

(4) Decision.-In any case where the court determines that the petitioner-

(A) is an alien who was not ordered removed under section 235(b)(1), or

(B) has demonstrated by a preponderance of the evidence that the alien is an alien lawfully admitted for permanent residence, has been admitted as a refugee under section 207, or has been granted asylum under section 208 , the court may order no remedy or relief other than to require that the petitioner be provided a hearing in accordance with section 240. Any alien who is provided a hearing under section 240 pursuant to this paragraph may thereafter obtain judicial review of any resulting final order of removal pursuant to subsection (a)(1).

(5) Scope of inquiry.-In determining whether an alien has been ordered removed under section 235(b)(1), the court's inquiry shall be limited to whether such an order in fact was issued and whether it relates to the petitioner. There shall be no review of whether the alien is actually inadmissible or entitled to any relief from removal. [Emphasis added.]

The expedited removal provisions in section 235(b) of the INA were added to the INA by section 302 of the Illegal Immigration Reform and Immigrant Responsibility Act of 1996 (IIRIRA) . Sections 242(a)(2)(A) and (e) of the INA were added by section 306 of IIRIRA. As the conference report for IIRIRA states:

Section 242(e)(3) provides for limited judicial review of the validity of procedures under section 235(b)(1). This limited provision for judicial review does not extend to determinations of credible fear and removability in the case of individual aliens, which are not reviewable. Section 242(e)(3) provides that judicial review is available only in an action instituted in the United States District Court for the District of Columbia, and is limited to whether section 235(b)(1), or any regulations issued pursuant to that section, is constitutional, or whether the regulations, or a written policy directive, written policy guidance, or written procedures issued by the Attorney General are consistent with the INA or other law. Any action seeking such review must be filed within 60 days of the implementation of the regulations, directive, guidance, or procedures. [Emphasis added.]

Matter of A-B- was not a written policy directive, written policy guidance, or written procedures to implement the expedited removal provision, and as noted, it did not deal with credible fear. That it was applicable to credible fear was simply because the INA and regulations, as stated above, give the AG the authority over all questions of law, and makes his decisions binding, with limited exceptions, over all immigration officers In the Department of Homeland Security (DHS) as well as DOJ. As the government argued, it was "an adjudication that determined the rights and duties of the parties to a dispute."

Nonetheless, Judge Sullivan concluded that the court had jurisdiction to review Matter of A-B- under section 242(e)(3) of the INA. Specifically, he noted portions of that decision where the AG referenced credible fear, holding:

Because the Attorney General cited [section 235(b) of the INA] and the standard for credible fear determinations when articulating the new general standard, the court finds that Matter of A-B- implements [section 235(b) of the INA] within the meaning of [section 242(e)(3) of the INA].

He also rejected the government's argument that Matter of A-B- was an adjudication, not a policy, finding that it was "well-settled that an 'administrative agency can, of course, make legal-policy through rulemaking or by adjudication.'" He held:

Matter of A-B- is a sweeping opinion in which the Attorney General made clear that asylum officers must apply the standards set forth to subsequent credible fear determinations.

As noted above, it was not actually necessary for the AG to do so, because his opinion was effective in credible fear proceedings as a matter of law.

Further, he rejected the government's argument that it is the secretary of Homeland Security, and not the attorney general, who is responsible for implementing most of the expedited removal provisions in section 235 of the INA, and that the AG "lacks the requisite authority to implement" that section, such that Matter of A-B- "cannot be 'issued by or under the authority of the attorney general to implement'" section 235(b) of the INA. He did so on the slim reed that "immigration judges who review negative credible fear determinations [working for the AG] were also required to apply Matter of A-B-." Notwithstanding this incredibly minor role for DOJ in the credible-fear process, Judge Sullivan held: "Therefore, the Attorney General clearly plays a significant role in the credible fear determination process and has the authority to 'implement'" section 235.

He concluded:

Finally, the Court recognizes that even if the jurisdictional issue was a close call, which it is not, several principles persuade the Court that jurisdiction exists to hear plaintiffs' claims. First, there is the "familiar proposition that only upon a showing of clear and convincing evidence of a contrary legislative intent should the courts restrict access to judicial review." ... Here, there is no clear and convincing evidence of legislative intent in section [242 of the INA] that Congress intended to limit judicial review of the plaintiffs' claims. To the contrary, Congress has explicitly provided this Court with jurisdiction to review systemic challenges to section [235(b) of the INA].

This is an incredible statement in light of the significant limitations Congress has placed on judicial review of expedited-removal proceedings.

He continued:

Second, there is also a "strong presumption in favor of judicial review of administrative action." ... As the Supreme Court has recently explained, "legal lapses and violations occur, and especially so when they have no consequence. That is why [courts have for] so long applied a strong presumption favoring judicial review of administrative action." ... Plaintiffs challenge the credible fear policies under the APA and therefore this "strong presumption" applies in this case.

Again, there is a strong presumption in favor of judicial review of administrative action, except for when Congress says there isn't. Here, a significant portion of section 242 of the INA, which governs all judicial review of orders of removal, is dedicated to limiting the ability of courts to review expedited-removal cases.

He further stated: "Third, statutory ambiguities in immigration laws are resolved in favor of the alien. ... Here, any doubt as to whether [section 242(e)(3) of the INA] applies to plaintiffs' claims should be resolved in favor of plaintiffs." Respectfully, under this standard as applied, respondents would never lose any immigration case.

Having found that he had the authority in section 242(e)(3) of the INA to review the AG's order in Matter of A-B-, he concluded that certain credible fear policies therein violated the Administrative Procedures Act (APA) because they were arbitrary and capricious and violated the INA because they were contrary to law.

Under the expansive jurisdictional standard announced by Judge Sullivan, any precedential decision by the BIA or AG relating to asylum could be subject to review by the U.S. District Court for the District of Columbia under section 242(e)(3) of the INA in any case brought by any alien who had been denied a finding of credible fear in accordance with that decision, because that decision would, by operation of law, have an effect on credible-fear determinations.

That was the opposite of the intent of Congress in providing for expedited procedures for the removal of aliens seeking to enter or who had entered illegally without proper documents. DOJ must appeal, and the circuit court must restore the authority of the court to its proper limited role in expedited removal proceedings on review.