CDC orders directing the expulsion of illegal migrants, issued pursuant to Title 42 of the U.S. Code in response to the Covid-19 pandemic, will either soon end abruptly or they won’t. Title 42 is a public-health provision, not an immigration one, but in the absence of any coherent administration action on border security, it has played an outsized role in security at the U.S.-Mexico line. Title 42’s immigration twin is section 212(f) of the Immigration and Nationality Act (INA), and if you like the former, you’ll love the latter.

“Title 42”. “Title 42”, as used in common parlance these days, refers (in an example of rhetorical overload) to two related things: The CDC’s public-health border expulsion orders (the first of which was issued in March 2020) and 42 U.S.C. § 265, the public-health provision on which those orders are premised.

Here’s the language of that federal statute:

Whenever the Surgeon General determines that by reason of the existence of any communicable disease in a foreign country there is serious danger of the introduction of such disease into the United States, and that this danger is so increased by the introduction of persons or property from such country that a suspension of the right to introduce such persons and property is required in the interest of the public health, the Surgeon General, in accordance with regulations approved by the President, shall have the power to prohibit, in whole or in part, the introduction of persons and property from such countries or places as he shall designate in order to avert such danger, and for such period of time as he may deem necessary for such purpose.

The role of the surgeon general in making determinations under section 265 has been assumed by the director of the CDC, but otherwise that provision — passed five days before D-Day in 1944 — has been largely unchanged since it was added to federal law.

That said, the concept behind section 265 predates the provision itself, and predates the United States for that matter. It is closely linked to “quarantine”, the practice of preventing the entry of persons or goods into a territory for a fixed period (usually 40 days — quaranta giorni in Italian, hence the name), which the CDC itself explains began in the 14th century (in Venice during the Black death).

Why is so much attention being paid to a 1944 statute premised on a 14th century practice in the second decade of the 21st century? Because, almost immediately after taking office, President Joe Biden began dismantling a series of Trump administration policies that had brought order and security to the Southwest border. And in their stead, he did ... nothing.

Biden didn’t touch those CDC Title 42 orders for more than a year, however, likely because they’re premised on pandemic emergency orders the administration is using to maintain costly Medicaid expansions and forgive student-loan debt.

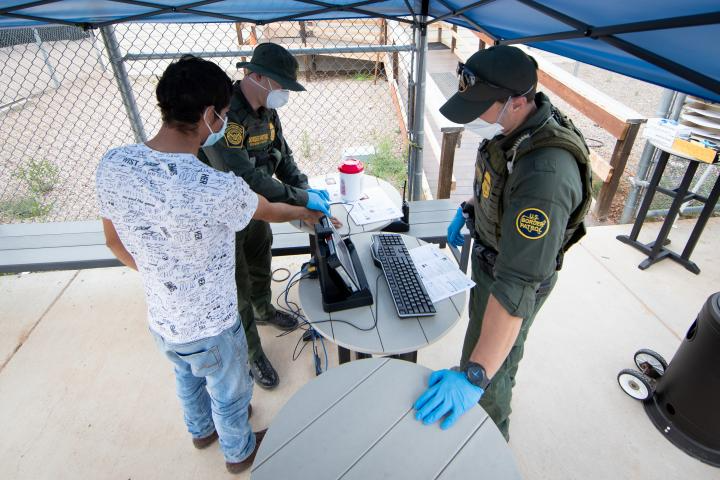

Consequently, the only relief that overwhelmed and overworked Border Patrol agents have had in dealing with increasing waves of illegal entrants has been expulsion under Title 42.

That changed in early April, when the administration announced that CDC would be ending Title 42 (the orders, not the statute) on May 23. This announcement sent a coalition of states to federal court in Louisiana, where a federal district court judge enjoined the termination of those Title 42 orders on May 20.

As if to prove that public-health orders and federal court decrees were no way to run an immigration system, a different federal district court judge (this one in the District of Columbia) issued his own decision in the middle of November, both vacating and enjoining expulsions under Title 42.

The validity of that order and the consequent viability of Title 42 is currently in the hands of the nine unelected justices of the Supreme Court. What they will do is anyone’s guess.

“We Will Go Back to Title 8”. For her part, White House Press Secretary Karine Jean-Pierre portrays the president as nothing more than a pawn in the hands of the federal judiciary as it mulls over the question of whether those CDC Title 42 orders will continue (or not).

Nonetheless, she insists that if those orders are terminated, “we will go back to Title 8, which allows a process to make sure that people can make their asylum claims heard. Those who do not have a legal basis to remain will be quickly removed.”

There’s a lot to unpack there, but I’ll leave most of it (particularly whether aliens whose asylum claims are denied are “quickly removed”, which they aren’t) for another day.

“Title 8” refers to the Immigration and Nationality Act, which is formally “Title 8 of the U.S. Code”, in the same way public health laws are in Title 42.

Jean-Pierre is correct that the INA (at sections 208 and 235) “allows a process to make sure that people can make their asylum claims heard”, but it also includes a mandate (found at 8 U.S.C. § 1701 note) directing the secretary of DHS “to achieve and maintain operational control over the entire international land and maritime borders of the United States”, defined as “the prevention of all unlawful entries into the United States”.

I’m unaware whether the press secretary has ever referenced that congressional directive (few do), but given the fact that agents at the Southwest border have apprehended more than 411,000 illegal entrants in the first two months of FY 2023 alone, a period in which more than 137,000 others (colloquially known as “got-aways”) entered illegally and evaded apprehension, DHS Secretary Alejandro Mayorkas is plainly not complying with Congress’ “operational control” mandate.

“Shall Take All Actions the Secretary Determines Necessary and Appropriate”. The likely reason why few people refer to the operational control mandate in the INA is that it seems impossible to meet. The Southwest border is 1,954 miles long, and is defended and secured (or not) by fewer than 17,000 Border Patrol agents. That may seem like straining rice with a tennis racket.

Congress did not leave either those agents or the secretary without tools to “achieve and maintain operational control” of the border, however. That directive language finds its genesis in the Secure Fence Act of 2006, a law passed on a bipartisan basis (then-Sen. Joe Biden voted “aye” and then crowed about it) that authorized a massive border infrastructure scheme.

Notably, however, the title notwithstanding, that act was not just about “fences”. Rather, Congress directed the secretary to “take all actions the Secretary determines necessary and appropriate to achieve and maintain operational control over the entire international land and maritime borders.” “All actions, necessary and appropriate” is a massive grant of congressional authority.

Section 212(f) of the INA. Speaking of massive grants of congressional authority, section 212(f) of the INA provides that:

Whenever the President finds that the entry of any aliens or of any class of aliens into the United States would be detrimental to the interests of the United States, he may by proclamation, and for such period as he shall deem necessary, suspend the entry of all aliens or any class of aliens as immigrants or nonimmigrants, or impose on the entry of aliens any restrictions he may deem to be appropriate.

To put section 212(f) into context, the preceding section 212(a) of the INA contains the grounds of inadmissibility, reflecting Congress’ determinations as to which aliens should be admitted to the United States and on what terms, and which aliens should be barred from admission.

Section 212(f) trumps all of them, at least when it comes to admissibility. Basically, in section 212(a) of the INA, Congress says that certain aliens may be admitted to the United States, but then allows the president say that none of them are.

How broad is the authority in section 212(f)? As the Supreme Court explained in its landmark 2018 decision in Trump v. Hawaii (assessing the legality of executive branch travel restrictions for given aliens from certain, mostly Muslim-majority countries, which were based on that provision):

[Section 212(f) of the INA] exudes deference to the President in every clause. It entrusts to the President the decisions whether and when to suspend entry (“[w]henever [he] finds that the entry” of aliens “would be detrimental” to the national interest); whose entry to suspend (“all aliens or any class of aliens”); for how long (“for such period as he shall deem necessary”); and on what conditions (“any restrictions he may deem to be appropriate”). It is therefore unsurprising that we have previously observed that [section 212(f) of the INA] vests the President with “ample power” to impose entry restrictions in addition to those elsewhere enumerated in the INA.

Again, Jean-Pierre is correct that “Title 8 ... allows a process to make sure that people can make their asylum claims heard” in sections 208 and 235 of the INA. What she misses, however, is that the authority in section 212(f) allows her boss to trump those provisions, and every other admission directive in the INA.

Congress has been floundering around trying to craft some immigration authority that would substitute for the public-health authorities in Title 42, to address the burgeoning surge of illegal migrants at the Southwest border.

Meanwhile, the White House has been portraying itself, Romeo-like, as “fortune’s fool”, subject to the whims of the federal judiciary on Title 42 and defenseless against any and all foreign nationals who seek to enter the United States illegally, while at the same time impotent to meet the “operational control” mandate.

None of it’s true. Section 212(f) of the INA gives the executive branch the authority to do — even absent a border emergency — what those CDC expulsion orders currently direct Border Patrol agents to do, that is, “suspend the entry of all aliens or any class of aliens” through expulsion.

And if Mayorkas (likely coming soon to a congressional hearing near you) contends there’s no “action” he can take to achieve and maintain operational control of the Southwest border, members of Congress and the press should ask him whether he has approached the president about issuing a section 212(f) proclamation.

Mayorkas’ contentions to the contrary, the immigration system is not “broken”, except to the extent the administration has been sabotaging it through feckless and willful inaction. In section 212(f) of the INA — a provision that “exudes deference to the President in every clause”, Congress gave Biden the tool he needs to stop the humanitarian disaster at the Southwest border. Now’s the time for him to pull it out of the “Title 8” toolbox.