In an April 8 post, I reported that Border Patrol apprehensions at the Southwest border in March were at a 20-year high. Even that does not tell the whole story. Here are some facts and charts that explain just how bad it was.

In March, more unaccompanied alien children (UACs) were apprehended by Border Patrol at the Southwest border (18,663) than in any month for which Border Patrol keeps records (back to FY 2010). The runner up (May 2019, with 11,475) was not even close — a difference of 7,188 apprehensions, or a 38.5 percent increase over the previous record.

On April 9, the Texas Tribune reported that the Biden administration is spending $60 million weekly to care for more than 16,000 UACs in shelters operated or contracted by the Department of Health and Human Services (HHS).

HHS has 7,700 beds in its permanent shelter network (which costs the department $290 a day), but the government has had to set up 10 emergency facilities for the rest (for about $775 per day, based on past history) for the overflow. That still left 4,000 in what it described as “cramped border facilities”.

Then, there are the families.

More adult migrants traveling as a family unit with children (FMUs) were apprehended last month (52,904) than in any other month for which Border Patrol maintains statistics (back to FY 2013), with the exception of four months (March through June) at the height of the border “crisis” in FY 2019 (and last month was pretty close to March 2019, when 53,204 FMUs were apprehended).

In fact, more migrants in family units were apprehended at the Southwest border in March than in all of FY 2013 and FY 2015, and just 1,789 fewer than in the two years combined.

More importantly, however, the number of migrants in FMUs apprehended by the Border Patrol last month almost tripled in number from February (19,286).

A March 25 Washington Post analysis piece shows, based on an eight-year survey, that February is the second-slowest month for illegal entries (they crater in January), but that entries generally increase by less than 30 percent between February and March. FMU apprehensions increased more than 174 percent between February and March this year, though.

There were also single adult migrants — 96,628 of them were apprehended by Border Patrol last month.

I would say that they are not as large a concern for Border Patrol, but that is not necessarily true. CBP is able to use Trump-era authorities under Title 42 of the U.S. Code (in orders issued by the director of the Centers for Disease Control in response to the pandemic beginning last March) to quickly expel most single adults who were apprehended back across the border to Mexico.

But even if they are being quickly expelled, Border Patrol still has to apprehend those adults first, which is particularly difficult because many if not most don’t want to be caught. And the agency's resources are already stretched thin caring for the families and children it has apprehended. It’s no wonder that Border Patrol morale is described as being “low”.

Plus, all of that assumes that single adult migrants are not being given “credible fear” interviews (which would allow them to remain in the United States to pursue asylum claims if approved) if they assert that they would be harmed if returned, either to Mexico or to their home countries (if they are not Mexican nationals). I have no reason to believe, however, that to be the case.

Of course, as DHS Secretary Alejandro Mayorkas asserted on March 16, family units are also subject to quick expulsion under Title 42 (he stated that fact a bit more dispositively, though with major caveats). But, on April 8, Reuters reported that only about 17,000 of the almost 53,000 FMUs that Border Patrol apprehended last month had been expelled under Title 42.

ICE is detaining families under an $86.9 million dollar contract with Endeavors Inc., which is to provide 1,200 beds in hotels for them. Those families are being housed for “less than 72 hours for processing”, after which many if not most are likely to be allowed to remain.

In addition, thousands of FMUs have been released by Border Patrol without even being served with a notice to appear (NTA, the charging document placing them into removal proceedings). Instead, they were told to show up at an ICE office in 60 days; it is questionable whether many will ultimately show.

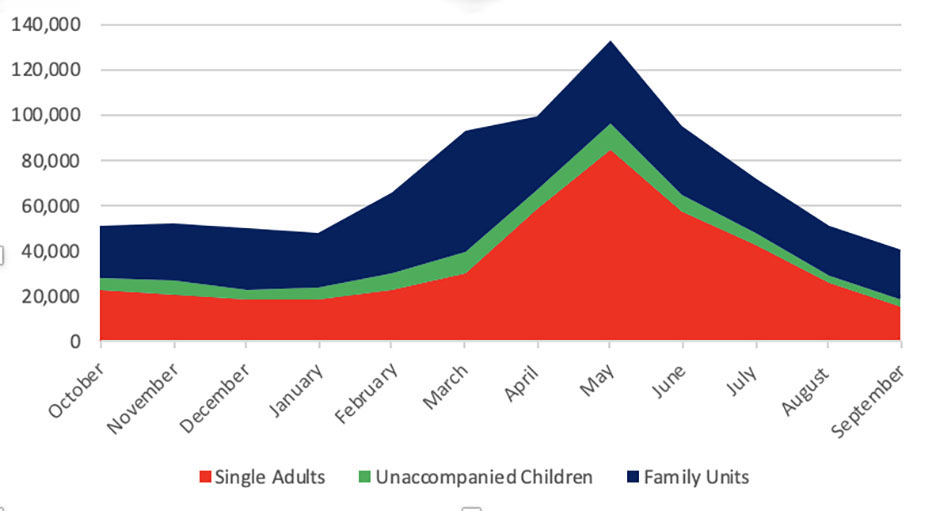

Without a change in policy, this situation is likely to just get worse. To explain why, here are two figures showing Border Patrol apprehensions by demographic (UAC, FMU, and single adults). The first is the most recent, for FY 2021.

Figure 1. Southwest Border Apprehensions, FY 2021 |

|

|

Source: U.S. Customs and Border Protection, Southwest Land Border Encounters, modified April 8, 2021. |

The second contains the same information for the same six-month period in FY 2019.

Figure 2. Southwest Border Apprehensions by Demographic, FY 2019 |

|

|

Source: U.S. Customs and Border Protection, Southwest Border Migration FY 2019, last modified November 14, 2019. |

There are two things to note. The first is that the total numbers on the “rise” on the second chart (the right-hand side numbers) are lower for FY 2019, because the total apprehensions in the first six months of that year were that much lower than they were in the same period this fiscal year.

The second is that there were more migrants in family units at the beginning of FY 2019 than there were in the first six months of FY 2021. The Washington Post analysis shows that migration generally bottoms out in January, but that is the month that family migration really got going in this year. Likely not coincidentally, it was also the first (partial) month of the Biden administration.

Why does this matter? Illegal migration was so bad in the first five months of FY 2019 (that is, October 2018 through February 2019), that DHS felt the need to put out a press release on March 6, 2019, captioned “Humanitarian and Security Crisis at Southern Border Reaches 'Breaking Point'”.

If the border reached a “breaking point” in February of that year, what words could be used to describe it this year, when the total number of illegal migrants generally and of UACs in particular is significantly higher, and the number of migrants in family units is near comparable levels to where they were in March 2019?

The situation at the border is unlikely to get better soon, unless the Biden administration changes its policies or Congress changes the laws that encourage aliens to enter illegally (as I recommended in my last post), and fast. Here’s how FY 2019 finished out.

Figure 3. Southwest Border Apprehensions by Demographic, FY 2019 Total |

|

|

Source: U.S. Customs and Border Protection, Southwest Border Migration FY 2019, last modified November 14, 2019. |

Why did it finish out on a lower note?

In late June, the Trump administration secured additional funding for shelters for unaccompanied children, and as the fiscal year went on, it worked with the Mexican government to secure its own southern border and to implement the Migrant Protection Protocols (MPP, or “Remain in Mexico”), as well as executing many other migration reduction initiatives.

Seasonal migration patterns may well explain some of the drop in apprehensions that began in June 2019, but it is beyond cavil that Trump’s changes in policies played a huge role, and MPP in particular.

Under that program, migrants who had claimed credible fear were returned to Mexico to await their asylum hearings.

The Migration Policy Institute reported in January that “at least 70,000 people” were “returned to Mexico to await court hearings”, and that of the “42,012 MPP cases that had been completed” by December 2020, “only 638 people were granted relief in immigration court” — a 1.5 percent grant rate.

Biden ended MPP and other Trump administration initiatives, as my colleague Rob Law explained on March 15 (with the notable exception of Title 42 expulsions), and with no similar programs to limit illegal migration to replace them, the floodgates opened just after the Biden administration began, in February.

I will complete the first figure in October, when FY 2021 ends. Unless Biden or Congress step in to stem the tide, expect the run to get a whole lot larger.