On Monday, CBP released the latest monthly report on CBP "encounters" (Border Patrol apprehensions and CBP port stops) along the Southwest border in November. The good news: Encounters went down ever so slightly, and in particular those involving unaccompanied alien children (UAC) and adult migrants traveling with children (FMU), between October and November. The bad news: The numbers are at eight-year highs for November, and are likely to get a whole lot worse.

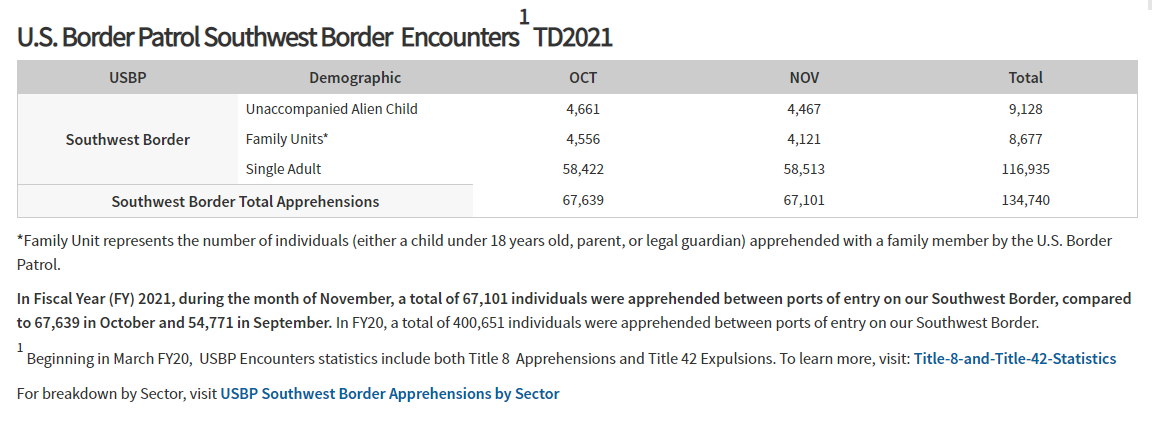

Quickly, the agency apprehended 70,052 migrants entering illegally or without documents last month, 487 fewer (.6 percent) than October, when 70,539 aliens were stopped. The number of UAC encounters decreased from 4,661 in October to 4,467, and the number of FMU dipped slightly (4,556 in October vs. 4,121 in November) as well.

The number of single adult migrants encountered increased, but again the difference was statistically insignificant: 58,513 in November, up from 58,422 in October. Maybe more migrants came, or maybe Border Patrol agents and CBP officers (CBPOs) were on their A-game.

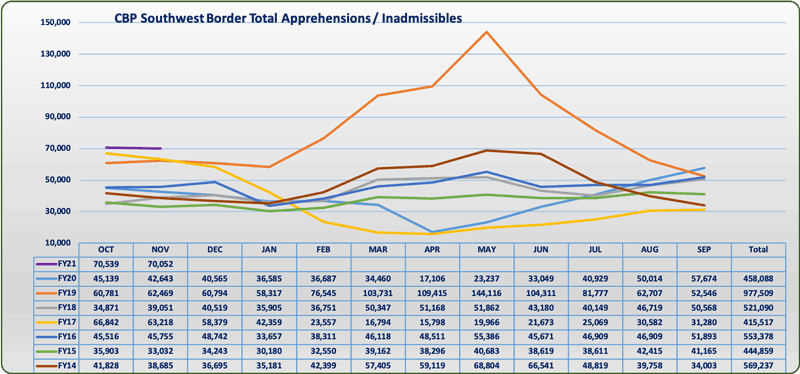

But these numbers are well above Novembers past. In FY 2015, after an Obama administration crack-down (of sorts) at the border, CBP had just 33,032 encounters at the Southwest border, meaning they increased 114 percent last month compared to six years before.

Only November 2019 — when there were 62,469 encounters — comes close, but even then, there was a 13-percent increase last month from the same month two years before. And that 2019 number was a harbinger of a humanitarian and national security disaster at the border in FY 2019, when the number of migrants apprehended overwhelmed DHS's capacity to deal with them.

One bipartisan federal panel in April that year found that the sheer number of migrants (and in particular FMU and UAC) in that surge "absorbed" 40 percent of Border Patrol resources, as agents had to take care of the migrants themselves. In places, half of CBP's agents and officers were not on the line at the border and ports. That diminished the agency's ability to disrupt smuggling attempts and drug and human trafficking, and to identify national security threats.

The numbers are especially troubling given the fact that CBP has some pretty strong tools in its arsenal to dissuade would-be illegal migrants. There is still a pandemic going on, and CDC has ordered the expulsion of illegal entrants and foreign nationals without proper documents under its Title 42 authority. In fact, in November, 58,094 migrants apprehended by Border Patrol were expelled under Title 42 ("only" 9,007 were processed under the Immigration and Nationality Act (INA)).

But still people keep coming. Why?

There are many reasons. Almost half of the UAC are coming from the so-called "Northern Triangle of Central America" (NTCA) countries of El Salvador, Guatemala, and Honduras, and 53 percent of the FMU are from the NTCA, as well. The World Bank reported that El Salvador's economy in 2020 is expected to contract by 8.7 percent, Guatemala's by 3 percent, and Honduras's by 7.1 percent, largely due to the effects of the pandemic. They will bounce back, but that will take time.

Acting CBP Commissioner Mark Morgan has blamed the UAC numbers, in particular, on a November decision from the U.S. District Court for the District of Columbia that bars CBP from expelling alien minors under Title 42. In April, CBP only encountered 712 UAC, compared, again, to 4,661 last month. To paraphrase the 1989 classic, "Field of Dreams": If you enjoin it — they will come.

Morgan also blamed the immigration platform of President-elect presumptive Joe Biden for the increase, channeling my colleague Todd Bensman's November warning of a "Biden effect" at the border. Purely objectively, Morgan and Bensman are correct.

Would-be illegal migrants are like any other economic actors, and as the incentives for illegal entry (the opportunity to live, work, and make more money in the United States) increase, the number who will invest in paying a smuggler to cross illicitly will, too. As Morgan explained, "cartels and human smugglers are fueling perceptions that our borders will once again be wide open, and that we will be reinstating the loopholes that have been closed."

It is unclear whether Biden will eliminate Title 42 right away (it will eventually get lifted as the pandemic wanes), but it does not appear that will make much of a difference. Morgan notes, for example, with respect to UAC:

Unlike last year when minors turned themselves over to Border Patrol agents, human smugglers are now packing them into over-crowded stash houses, hiding them under the floors of tractor trailers, or piling them into makeshift rafts where they can easily capsize in the Rio Grande River all to avoid apprehension.

The same is likely true for illegal migrants across the board.

Last Friday, for example, Border Patrol rescued 14 Mexican migrants (including a mother and her three-year-old daughter) in remote Copper Canyon, near Otay Mountain in California. On Sunday, agents stopped a "drive-through" by 19 illegal Mexican migrants in three separate vehicles in California's Jacumba Wilderness Area, on a section of the border where there is no fence. On December 9, agents disrupted a "stash house" in Laredo, Texas, apprehending 36 illegal aliens from Mexico, Guatemala, and Nicaragua.

Of course, the loopholes that Congress has failed to close don't help any of this, and more than likely promote it.

In November 2013, 783 FMU were apprehended by Border Patrol, total. Even with the pandemic, that number was up 426 percent last month from the same time six years before. Why?

There are a variety of factors, but the biggest (by far) is the 2016 Ninth Circuit decision in Flores v. Lynch, requiring that children in FMU to be released in 20 days. To avoid "family separation", the adults almost always get released, as well. Biden made his opposition to any "family separation" a key point in his immigration platform.

The Trump administration has issued regulations to address Flores, but they are bottled up in court, and will likely continue to remain bottled up under a Biden DOJ.

Similar factors explain the UAC increase.

In November 2010, 1,181 UAC were stopped by Border Patrol, 23 months after the Trafficking Victim Protection Reauthorization Act of 2008 (TVPRA) took effect. TVPRA requires DHS to hand UAC from the NTCA (among others) over to the Department of Health and Human Services for placement in shelters and, ultimately, with sponsors in the United States (the vast majority themselves here illegally).

Some 143 months after the TVPRA, as noted, CBP apprehended 4,661 UAC, almost three times the number just 10 years before. Could there be a link?

One expert I spoke to analogized non-enforcement of the immigration laws to a hypothetical non-enforcement of the drinking age (currently 21 years old nationally). If a state announced tomorrow that it would not enforce that age limit, teens wouldn't believe it, initially. After the first 18-year-old walks out with a bottle of Jack Daniels, though, others will notice and follow suit. Soon, booze sales among the "Gen Z" crowd will be through the roof.

That is what has happened with UAC and FMU at the border (in particular). Illegal entries did not quickly jump when changes were made, but when migrants and smugglers figured out what they could now get away with, they skyrocketed. With due respect to the former vice president, given his immigration (non-enforcement) proposals, those numbers will just get worse.

You have to go back to November 2006 to find monthly Border Patrol apprehensions at the Southwest border (70,975) in any November higher than last month (67,101, the vast majority of the 70,052 CBP "encounters"). FY 2006 finished with 1,071,972 Southwest border apprehensions, compared to "just" 400,651 in FY 2020.

Even that does not describe how bad the current trend lines are. In FY 2006, almost all migrants apprehended (90.8 percent) at the Southwest border were from Mexico, and as recently as FY 2012, 90 percent of all those apprehended were single adults — the historical trend up to that point.

Non-Mexican foreign nationals (OTMs) take longer for Border Patrol to process than Mexican nationals (who take on average eight hours to process and most of whom are simply sent back across the border when done). OTM FMU, by contrast, take an average of 78 hours of Border Patrol processing time, and even in the unlikely event they are actually subject to "expedited removal", their physical deportation can take days to weeks.

Granted, single adults were 87 percent of Border Patrol's Southwest border apprehensions in November. But given the fact that Biden is highly unlikely to amend TVPRA (he opposes the detention of minors in general), and opposes Trump's Flores changes (which he describes as a "circumvent[ion] of the Flores agreement"), those trend lines are extremely unlikely to last. The hypothetical liquor store is about to get less choosy about its underage clientele.

So the good news is that CBP encounters at the Southwest border remained relatively constant during the last two months. The bad news is that November's numbers are well above those in the same month in recent years, and with respect to Border Patrol apprehensions, at a 14-year high. The worse news is that even the good news is unlikely to last.