Normally when an illegal garbage dump catches fire and causes serious damage to public property, the blame falls on the various government agencies responsible for public health and safety. In 1989, agencies in the State of New Jersey tried to close down an illegal dump in Newark that was underneath I-78 near the airport. They were blocked by a state court judge who held it was a "legitimate enterprise 'that should be encouraged.'" Shortly thereafter, the garbage pile caught fire and caused the bridges above to buckle and the federal government had to spend millions of dollars to repair the damage. New Jersey's chief justice described the episode as a "serious judicial error". Here, the court, not the agencies, suffered the public wrath for causing a disaster that inflicted a traffic nightmare on the state.

Yesterday the Ninth Circuit held oral arguments on the federal government's attempt to remove a temporary restraining order or an injunction (it is not clear which we are dealing with) imposed by District Judge James Robart blocking the implementation of President Trump's executive order governing border security. The political question here for the Ninth Circuit is whether they want to own responsibility for border security.

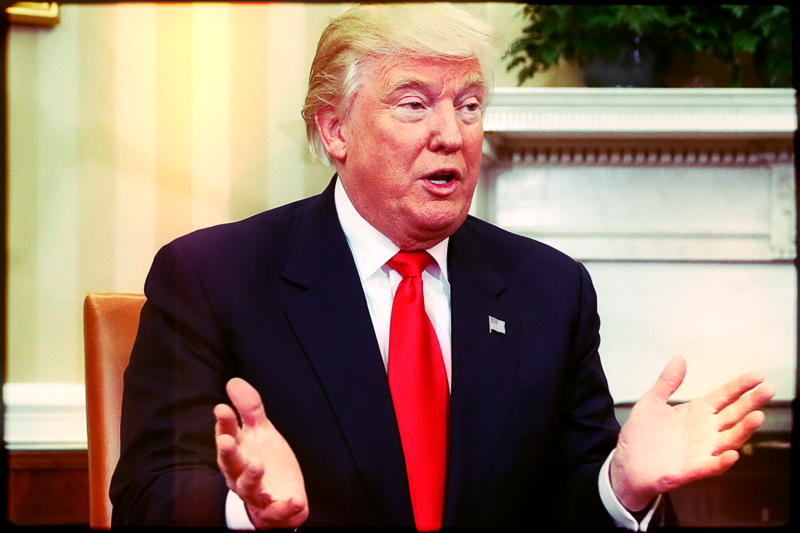

Right now, the buck stops at President Trump's desk. If some foreign national commits a terrorist act, Donald J. Trump will get the blame, even if the perpetrator came in to the country during a previous president's administration.

Congress has been explicit in regard to the president's power here:

Whenever the President finds that the entry of any aliens or of any class of aliens into the United States would be detrimental to the interests of the United States, he may by proclamation, and for such period as he shall deem necessary, suspend the entry of all aliens or any class of aliens as immigrants or nonimmigrants, or impose on the entry of aliens any restrictions he may deem to be appropriate.

The statute here is unambiguous: The president may exclude any alien from entry into the country. (Somehow, Judge Robarts has determined that "any alien" does not mean "any alien", but I will return to that.)

Politically, if the Ninth Circuit does decide that they, not the president, have the power to decide who can enter the country, they are now responsible. If any future terrorist attacks are made by or assisted by foreign nationals, they would be responsible. Should such an event occur, you can be sure that President Trump will rightfully blame the "idiot judges on the Ninth Circuit". The real issue before the Ninth Circuit is whether they want to take on this responsibility.

This question has to be analyzed in terms of politics because there is no legal analysis to debate. In order to get an injunction, the party must show they are likely to prevail on the merits. When the statute says the president can exclude any alien from the country, what other principle of law says otherwise?

We have no idea. Judge Robart simply wrote, "The States have satisfied the Winter test because they have shown that they are likely to succeed on the merits of the claims that would entitle them to relief." That kind of writing would, quite literally, get you a D in law school (stated the rule, no analysis).

One might excuse the judge on the grounds of time, but this order has not been followed up by any opinion explaining how he reached his decision.

One of the problems in the federal courts is that there are too many judges who seek to provide outcomes, rather than consistent law. If you take the same question of law to multiple judges, you can get entirely different answers.

The District Court in Massachusetts issued a temporary restraining order against the executive order. However, it allowed the order to expire and issued an opinion. The Massachusetts court noted settled law that existed before Trump was elected:

It is "beyond peradventure" that "unadmitted and non-resident aliens" have no right to be admitted to the United States. Adams v. Baker, 909 F.2d 643, 647 (1st Cir. 1990)

But if it does not work in Boston, then try it in Seattle.

When we bring cases challenging government action, the biggest issue is always standing. We spend more time on standing then actually arguing the merits of the case. In Texas v. United States, the Fifth Circuit devoted 17 pages to analyzing whether the states had standing. But there was nothing like that here.

In the video of the District Court hearing the standing issue comes up (at 1:00:54). Judge Robart says "It is an interesting question in regard to the standing of the states to bring this action." Then he immediately goes on to say, "I'm sure the one item that all council will agree on is the standing law is a little murky." Then he finds the plaintiffs have standing.

Judge Robart demonstrated that standing is pure hokum. If a court wants a case to move on, standing is "murky" and the plaintiff goes forward. If a court does not want a case to move on, the court simply invents a new rule out of thin air to deny standing.