The Impact of Immigration Enforcement on California Children

Remarks of

Jessica M. Vaughan

Director of Policy Studies, Center for Immigration Studies

Before the California Advisory Committee to the U.S. Commission on Civil Rights

October 16, 2019

Los Angeles, Calif.

Thank you for the opportunity to participate in this meeting. The committee is examining some very serious questions: (a) the impact of ICE enforcement practices on access to public education for California K-12 students; (b) access to equal protection under the law for individuals based on their perceived national origin; and (c) the extent to which denial of due process is afforded to K-12 students and their families.

Considering the importance of these issues, the first step must be to establish an accurate, fact-based, and unembellished baseline of understanding of immigration enforcement today. As the committee is aware, as a matter of policy, ICE does not make arrests near schools and other sensitive locations. Federal law and ICE policies prohibit discrimination based on race, ethnicity, or national origin (perceived or known), and I am unaware of any substantiated incidents of racial profiling or discrimination by ICE or any immigration agency in recent history. As a matter of policy and practice, ICE does not target victims and witnesses to crimes, and I am unaware of any incidents of innocent victims or witnesses being deported, unless those individuals were also involved in crime. The vast majority of people removed by ICE were identified because of their involvement in local crimes, and most of the others were chronic immigration scofflaws.

As for due process concerns, in my experience most Americans are surprised at the generous due process that our system accords to non-citizens who knowingly enter illegally; who overstay the duration of legal visas; who violate the terms of their admission, often by working illegally or committing crimes; and who make false claims, misrepresent their identity and intentions, and commit fraud. Only a fraction of those who are caught crossing the land border illegally are removed quickly; nowadays, most are allowed to enter the country and stay for years while they await immigration proceedings.1 Congress created accelerated forms of due process for those who enter illegally after deportation, for aggravated felons, and certain other egregious cases, but most of those apprehended by ICE in the interior are placed in immigration proceedings that offer multiple hearings, opportunity to secure counsel, opportunities for multiple appeals and motions to re-open, and opportunities for exceptions and forgiveness of violations, including parole, temporary status, cancellation of removal, deferred action, stays of deportation, voluntary departure, asylum, and more. Many of those placed in removal proceedings are allowed to apply for work permits and can obtain driver's licenses and welfare benefits for the duration of their case, which typically lasts for several years. Fewer than 2 percent of ICE's docket is in detention, and about half of those are non-discretionary and required by statute.2

Unfortunately, much of the research cited in the documents supporting the committee's proposal to review these issues presents a distorted picture of immigration enforcement, suggesting that immigration enforcement is random, ubiquitous, overzealous, and risks disrupting the lives of many children in California. This is misleading; specifically, it overstates the scope of enforcement and undervalues the benefits of enforcement, especially the public safety benefits to everyone in the community, and particularly school children. This hearing, too, seems engineered to produce a set of recommendations that will further restrict immigration enforcement under the guise of concerns about alleged civil rights violations and the traumatization of children whose family members are potentially subject to immigration enforcement.

Whether well-meaning or contrived for political purposes, the narrative of mass, ubiquitous arrests and deportations is not only inaccurate, it is unhelpful to immigrants. It stokes fear and even panic among immigrants, legal and illegal. As we know from experience here in California, it also leads to policies that make things worse, as I will discuss below.

Immigration Enforcement Serves Important National and Social Interests

Immigration enforcement supports a number of very important public policy goals and is generally viewed positively by the public. First, our immigration laws are intended to protect job opportunities for Americans and legal immigrants, and help prevent labor market distortions that suppress wages. This is especially important to those Americans who have not had the benefit of higher education or may not have finished high school, who often are competing directly with immigrants, including illegal immigrants, for employment in occupations such as construction, manufacturing, restaurant and hotel work, and landscaping. Research by economists has found that illegal immigration reduces the wages of U.S. workers, especially native-born men, and especially those who lack a high school diploma, who are among the poorest Americans.3 When we allow employers to hire illegal alien workers with impunity, increasing un- and under-employment and suppressing wages, it is harder for Americans and legal immigrants to support their families, which stresses the entire household, including the children.

Second, immigration enforcement contributes to public safety through the removal of non-citizens who are a criminal or national-security threat. The Trump administration has continued the practice of every other administrations before it in making the removal of criminal and security threats the most important priority for enforcement. Nearly all of the individuals removed by ICE from the interior of the country in the last five years were apprehended through one of the many enforcement programs targeting criminal aliens (see below).

Finally, immigration enforcement preserves the integrity of our legal immigration system, which admits about one million legal immigrants and about 750,000 legal long-term visa holders each year. Some four million people currently are on the waiting list to receive green cards, after passing background checks, medical checks, and paying thousands of dollars in fees. Ignoring illegal immigration is unfair to those who come legally and undermines public support for legal immigration in general.

Setting the Record Straight on the Scale and Scope of Enforcement

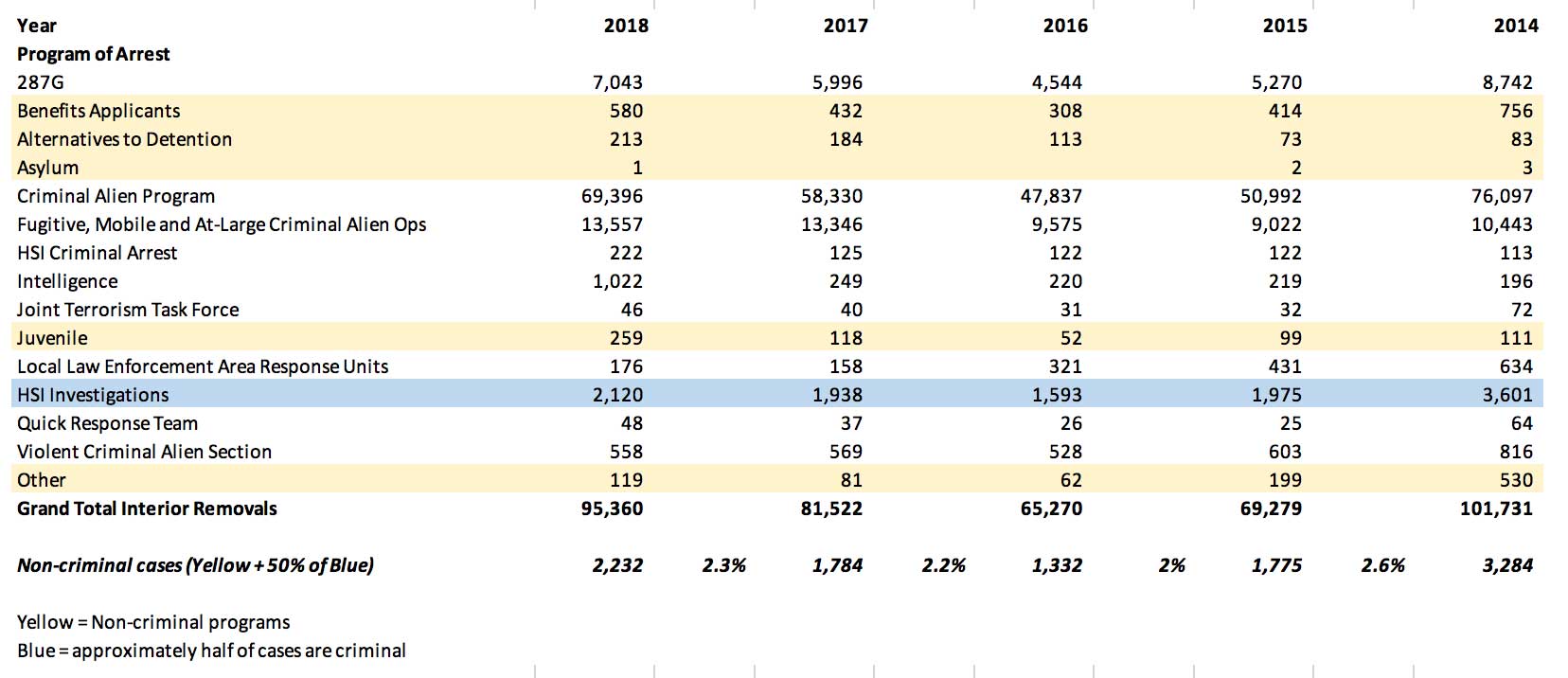

Interior immigration enforcement is focused overwhelmingly on identifying, arresting, and removing that small fraction of non-citizens who are involved in crime. According to data that I extracted from ICE records obtained through the Freedom of Information Act, about 97.5 percent of interior deportations over the last five years were aliens who were either incarcerated or who were arrested in one of ICE's programs targeting criminals. Table 1 shows a year-by-year breakdown of interior deportations according to the program of arrest.4

Table 1. ICE Interior Removals by Criminal and Non-Criminal Program: 2014-2018 |

|

Clearly only a fraction of ICE activity is of the type that would produce non-criminal arrests. Most non-criminal arrests occur in worksite operations (a tiny share of the activity of the Homeland Security Investigations division of ICE), national security investigations, or as a result of immigration benefit fraud detection.

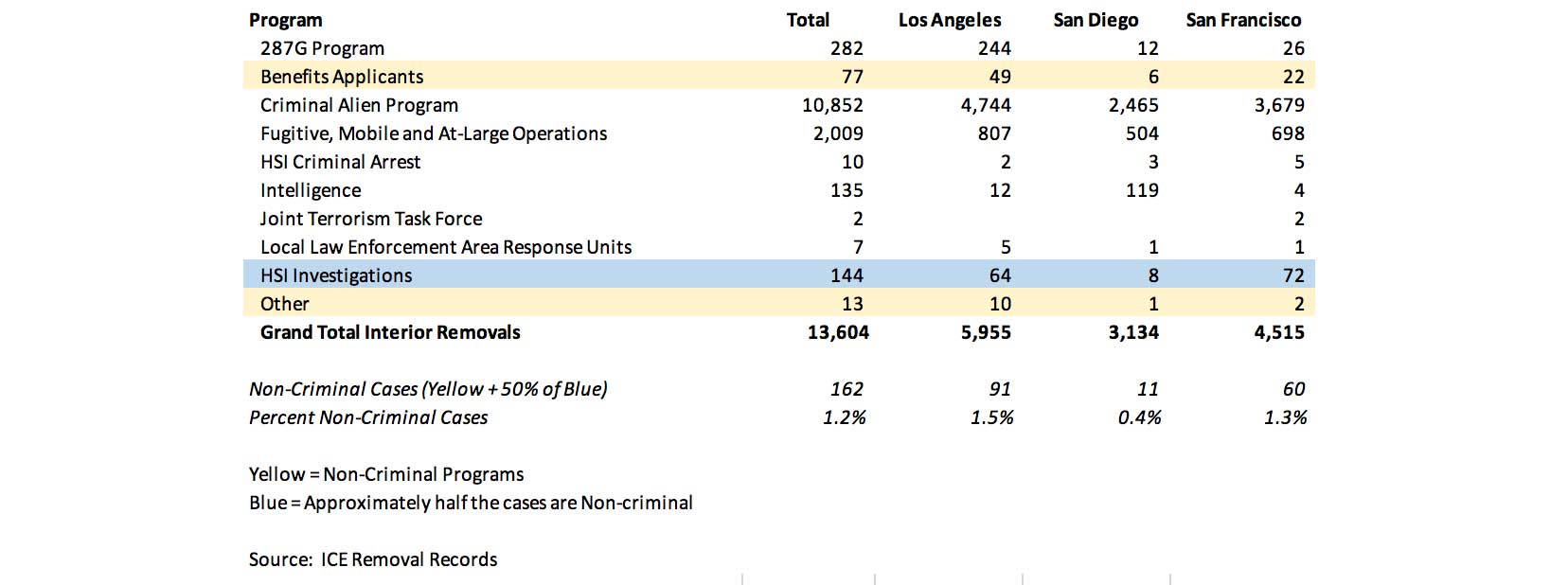

The percentage of non-criminal deportations by the California ICE field offices is even smaller. According to the ICE records, 98.2 percent of those deported from the region covered by the California field offices (which includes Nevada) in 2018 were arrested in one of the criminal targeting programs. Table 2 provides the breakdown.

Table 2. ICE Interior Removals by Criminal and Non-Criminal Program in California/Nevada Field Offices: 2018 |

|

The suggestion that ICE is engaged in random arrests, neighborhood sweeps, or operations targeting children, or even likely to be witnessed by children, is simply wrong. It is true that ICE sometimes does arrest people who have children living with them, but the reason these individuals are on ICE's target list is typically because they are involved in crime. ICE's primary concern is the safety of all people in the community. As in the larger justice system, no one is immune from consequences of law-breaking merely because they have a family.

Recent Increase in Public Arrests by ICE Due to Sanctuary Policies

A number of municipalities have reported increasing instances of ICE arrests in public places, especially courthouses. ICE records confirm that there have been a few more "at-large" arrests, especially in California.

This is not a coincidence, but a deliberate response by ICE. The agency has had to adjust its practices due to the imposition of restrictive sanctuary policies in California and other jurisdictions. These policies prohibit local law enforcement agencies from complying with ICE detainers and warrants, which are issued by ICE agents after developing probable cause that an alien already held in local custody is deportable. The detainer is a request and notice to the local agency to hold the alien for no longer than 48 hours until ICE can assume custody. Under California law, local law enforcement agencies are not permitted to honor ICE detainers and warrants in most circumstances, nor to routinely give ICE information on the release dates of criminal aliens. Some California jurisdictions have even more restrictive policies that prohibit local officers from communicating with ICE.

As a result of the California sanctuary policies, most of the criminal aliens that ICE is seeking to arrest are released from jails instead of being transferred to ICE custody. This means that ICE needs to expend additional resources locating and arresting deportable criminals in the community: at their dwellings, at their workplace, or in other public places. This type of enforcement is intimidating to the public, expends more resources, and is more dangerous, both for ICE officers and for the public. It also increases the chances that illegal residents who were not the original target will be encountered by ICE and put into removal proceedings, too, because ICE officers cannot look the other way when violations are discovered (typically those arrested in such situations, known as collateral arrests, are not detained unless they are deemed a public safety threat or egregious violator).

Sanctuary Policies Cause Public Safety Problems

In the wake of a litany of incidents of heinous crimes that were committed by criminal aliens released instead of held for immigration officers, including several in California, ICE recently launched a campaign to inform the public about the problems created by the sanctuary policies. On September 26, 2019, David Marin, the field office director for ICE's Enforcement and Removal Operations in the Los Angeles area stated at a press conference: "This year, ICE lodged over 11,000 detainers with the Los Angeles County Sheriff's Department, but unfortunately, less than 500 of those detainers have been honored." Marin provided several examples of criminal aliens sought by ICE who were released due to the California law and policies, including a four-time deportee with 12 prior arrests and four DUI convictions (three of which were in early 2019), and a five-time arrestee with charges including DUI and child cruelty involving injury or death.5

Those criminals who are not quickly re-apprehended by ICE after local release have the opportunity to re-offend in the community and create new victims.6 Like American offenders, criminal aliens have high recidivism rates. Since 2014, more than 10,000 individuals sought by ICE and subject to a detainer who were released nationwide due to sanctuary policies were subsequently arrested again for a new crime.7 A 2014 study by ICE provides statistics and examples of crimes that occurred subsequent to a criminal alien's release from local custody. Nationwide, there were 1,867 offenders who were released and subsequently re-offended during the eight-month period studied. These offenders were arrested an additional 4,298 times during those eight months. Together they accumulated 7,491 new charges after release. Ten percent of the new charges involved dangerous drugs and 7 percent were for driving under the influence of alcohol (DUI).

Clearly, there can be grave consequences for children when criminals who should be deported are instead released to the community. The ICE report describes five instances of very serious crimes committed by criminal alien felons who were sought by ICE with a detainer, but nevertheless released by a California law enforcement agency:

- Santa Clara County: On April 14, 2014, an individual with nine previous convictions (including seven felonies) and a prior removal was arrested for "first degree burglary" and "felony resisting an officer causing death or significant bodily injury". Following release, the individual was arrested for a controlled substance crime.

- Los Angeles: On April 6, 2014, an alien was arrested for "felony continuous sexual abuse of a child". After release, the alien was arrested for "felony sodomy of a victim under 10 years old".

- San Francisco: On March 19, 2014, an illegal alien with two prior deportations was arrested for "felony second degree robbery, felony conspiracy to commit a crime, and felony possession of a narcotic controlled substance", After release, the alien was again arrested for "felony rape with force or fear", "felony sexual penetration with force", "felony false imprisonment", witness intimidation, and other charges.

- San Mateo County: On February 16, 2014, an individual was arrested for "felony lewd or lascivious acts with a child under 14". In addition, the alien had a prior DUI conviction. Following release by the local agency, the individual was arrested for three counts of "felony oral copulation with a victim under 10" and two counts of "felony lewd or lascivious acts with a child under 14".

- Santa Clara County: On November 7, 2013, an alien was arrested (and later convicted) for "felony grand theft and felony dealing with stolen property". This alien had been ordered removed in 2010 (again, a likely absconder). The alien also had prior felony and misdemeanor convictions for narcotic possession, theft, receiving stolen property, illegal entry, and other crimes. After release by local authorities, the alien was arrested for "felony resisting an officer causing death or severe bodily injury" and "felony first degree burglary".

ICE Gang Programs Help Keep Schools and Students Safe

ICE makes a noteworthy contribution to school safety through its program targeting transnational gangs, known as Operation Community Shield.8 ICE has been especially active in recent years investigating and disrupting certain gangs, including MS-13 and 18th Street, that have a significant number of members who entered illegally or lack status; that are particularly violent; and that actively recruit, act up, and intimidate others in schools.

Law enforcement agencies report that certain communities, including some in California, have experienced a noticeable increase in MS-13 and 18th Street gang activity since the influx of unaccompanied minors from Central America began in 2012. It has been established that the gang leaders in Central America deliberately exploited loopholes in U.S. immigration policy to boost their ranks in the United States. These loopholes allowed minors who arrived illegally without parents to settle here, either with parents already residing here, with other family members, or with sponsors who agreed to look after the minors – without home studies, without monitoring, and without background checks by the government. The U.S.-based cliques absorbed thousands of newly arrived teenagers as a result. Some were already affiliated with the gangs in their home countries, some already had criminal records there, and some were new recruits from the thousands of youths who were brought by their parents.9

The result has been an epidemic of extreme gang violence and a deterioration in quality of life in some of these communities, including a degradation in school safety. Last year I conducted a study of more than 500 MS-13 arrest cases that were reported in open sources from 2012 to 2018. Among these cases we found dozens of arrests of juvenile gang members, and dozens of young people who were victimized, including 52 murder victims who were under the age of 18.10

Eighty-seven of 500 MS-13 gang members were arrested in California. One of the most horrific cases took place in Novato in May 2016. Two 17-year-old Novato High School students, Edwin Ramirez Guerra and Llefferson Diaz, were ambushed, shot and hacked on a hiking trail by two of their fellow students, and Ramirez was killed. Just 10 days before the attack, one of the suspects, Juan Carlos Martinez Henriquez, also 17 at the time, had been arrested for the rape and sodomy of a 15-year-old Novato High School student, but was released from juvenile hall after two days. Two teen-aged brothers were charged, Edwin Guevara (then age 17), and his brother, Javier Guevara (then age 19), who is now a fugitive. Their cousin, Elmer Machado-Rivera, age 24, pled guilty to being an accessory to the murder. The man accused of being the shot-caller, Edenilson Misael Alfaro, age 23, already had a violent rap sheet, including pending murder charges in Washington state. He attempted to murder one of his accomplices, and was for a time incarcerated at the Marin County Jail, from which he attempted a violent escape. He was arrested in Maryland six months after the Novato murder. A number of other young adults have been found or have pled guilty in connection with this attack.

Two of the suspects in the case were arrested by a special tactical team at a location that was just blocks away from Novato High School. While it is rare for authorities to make arrests in the vicinity of a school, there are times when it is necessary, to avoid losing an opportunity to make the arrest, or to avoid danger to the public. It is especially rare, almost unheard of, for ICE to make arrests near a school. Such arrests must be approved in advance by senior ICE managers at the headquarters level.

Claims of "Chilling Effect" on Crime Reporting Are Unsubstantiated

Opponents of immigration enforcement commonly assert that sanctuary or non-cooperation policies are necessary for immigrants to feel comfortable reporting crimes. This frequently heard claim has never been substantiated, and actually has been refuted by a number of reputable studies. No evidence of a "chilling effect" from local police cooperation with ICE exists in federal or local government data or independent academic research.

It is important to remember that crime reporting can be a problem in any place, and is not confined to any one segment of the population. In fact, most crimes are not reported, regardless of the victim's immigration status or ethnicity. According to the most recent Bureau of Justice Statistics (BJS) data, in 2018 only 43 percent of all violent victimizations were reported to police.11 In addition, earlier data from the Bureau of Justice Statistics shows no meaningful differences among ethnic groups in crime reporting. Overall, Hispanics are slightly more likely to report crimes. Hispanic females, especially, are slightly more likely than white females and more likely than Hispanic and non-Hispanic males to report violent crimes.12 This is consistent with academic surveys finding Hispanic females to be more trusting of police than other groups.13

A multitude of other studies refute the notion that local-federal cooperation in immigration enforcement causes immigrants to refrain from reporting crimes:

- A major study completed in 2009 by researchers from the University of Virginia and the Police Executive Research Forum (PERF) found no decline in crime reporting by Hispanics after the implementation of a local police program to screen offenders for immigration status and to refer illegals to ICE for removal. This examination of Prince William County, Va.'s, 287(g) program is the most comprehensive study to refute the "chilling effect" theory. The study also found that the county's tough immigration policies likely resulted in a decline in certain violent crimes.4

- The most reputable academic survey of immigrants on crime reporting found that by far the most commonly mentioned reason for not reporting a crime was a language barrier (47 percent), followed by cultural differences (22 percent), and a lack of understanding of the U.S. criminal justice system (15 percent) — not fear of being turned over to immigration authorities. (Davis, Erez, and Avitable, 2001)

- The academic literature reveals varying attitudes and degrees of trust toward police within and among immigrant communities. Some studies have found that Central Americans may be less trusting than other groups, while others maintain that the most important factor is socio-economic status and feelings of empowerment within a community, rather than the presence or level of immigration enforcement. (See Davis and Henderson 2003 study of New York; Menjivar and Bejarano 2004 study of Phoenix)

- A 2009 study of calls for service in Collier County, Fla., found that the implementation of the 287(g) partnership program with ICE enabling local sheriff's deputies to enforce immigration laws, resulting in significantly more removals of criminal aliens, did not affect patterns of crime reporting in immigrant communities. (Collier County Sheriff's Office)

- Data from the Boston, Mass., police department, one of two initial pilot sites for ICE's Secure Communities program, show that in the years after the implementation of this program, which ethnic and civil liberties advocates alleged would suppress crime reporting, calls for service decreased proportionately with crime rates. The precincts with larger immigrant populations had less of a decline in reporting than precincts with fewer immigrants. (Unpublished analysis of Boston Police Department data by Jessica Vaughan, 2011)

- Similarly, several years of data from the Los Angeles police department covering the time period of the implementation of Secure Communities and other ICE initiatives that increased arrests of aliens show that the precincts with the highest percentage foreign-born populations do not have lower crime reporting rates than precincts that are majority black, or that have a smaller foreign-born population, or that have an immigrant population that is more white than Hispanic. The crime reporting rate in Los Angeles is most affected by the amount of crime, not by race, ethnicity, or size of the foreign-born population. (Unpublished analysis of Los Angeles police department data by Jessica Vaughan, 2012).

- Recent studies based on polling of immigrants about whether they might or might not report crimes in the future based on hypothetical local policies for police interaction with ICE, such as one recent study entitled "Insecure Communities", by Nik Theodore of the University of Illinois, Chicago, should be considered with great caution, since they measure emotions and predict possible behavior, rather than record and analyze actual behavior of immigrants. Moreover, the Theodore study is particularly flawed because it did not compare crime reporting rates of Latinos with other ethnic groups.

For these reasons, law enforcement agencies across the country have found that the most effective ways to encourage crime reporting by immigrants and all residents are to engage in community outreach, hire personnel who speak the languages of the community, establish anonymous tip lines, and set up community sub-stations with non-uniform personnel to take inquiries and reports — not by suspending cooperation with federal immigration enforcement efforts.

Recommendations

- To reassure and avoid misleading the public, the committee should make a clear statement acknowledging that ICE does not routinely or frequently make arrests in sensitive locations like schools, hospitals, and churches, and that minors generally are not at risk of arrest unless they are involved in violent crime. Avoid recommendations for policy changes that would impose unreasonable operational limitations on ICE and force ICE into more dangerous environments.

- Address the issue of community fear in a constructive way. Encourage advocacy groups to engage with ICE's community relations officers and to help schools and community groups understand how and why ICE does its job, and tamp down rumors that stoke fear. In particular, advocacy groups should help spread the message that victims and witnesses of crime are not targets of ICE. No one should be afraid of reporting crimes, regardless of immigration status, and there are visas and other special protections available to crime victims who assist police in prosecuting offenders.

- It is also important to balance the understanding of ICE priorities with the understanding that immigration enforcement is not going away, and no one who has violated our immigration laws is necessarily immune from it. Therefore, the committee should encourage advocacy groups to urge families that include illegal residents to have a plan for what may happen in the event of enforcement and removal.

- The committee should urge ICE to release more information to the public about those arrested in immigration operations, so that the public can understand who was targeted and why. This recommendation should encourage ICE and other immigration agencies to comply more fully with Section 14 of the president's executive order dated January 25, 2017, which calls for increased transparency.15

- The committee should recommend that the Trump administration and other states pursue legal action and other appropriate initiatives to prohibit, penalize, or discourage sanctuary and non-cooperation policies, which lead ICE to conduct more at-large operations and arrests in public places.

- The committee should endorse and call for more funding for ICE's anti-gang operations. In addition, the committee should endorse legislation such as the "Criminal Alien Gang Member Removal Act" of 2017.16 And Congress should provide additional funding earmarked for ICE's National Gang Unit to focus on arrest, prosecution, and removal of juvenile gang members and transnational gang-related violence in schools.

- Similarly, the committee should back legislation that would expedite the removal of domestic violence officers, and should call for additional funding for ICE to boost removals of domestic violence offenders.

- Days before this hearing, Governor Newsom signed a new state law prohibiting private detention facilities in California. This misguided law will not achieve the legislature's goal of reducing immigration detention in California, much of which is mandated by federal law. Instead, it will mean that immigration detainees will be held in custody outside the state, and potentially located a long distance away from the detainees' family and attorneys. This separation from support networks will not only make it harder to ensure representation in immigration proceedings, it will inevitably strain family relationships and lead to emotional stress, especially for children. The committee should condemn this legislation because of the effects on families and on representation, and call for other states to refrain from adopting similar legislation.

Appendix: Definition of ICE Interior Arrest Programs Listed in Tables 1 and 2

287(g) Program: A voluntary partnership enabling designated local law enforcement officers to be trained as immigration officers, authorizing them to identify deportable aliens and initiate deportation proceedings if appropriate, under the supervision of ICE.

Benefits Applicants: Individuals referred for deportation by USCIS who were identified while seeking green cards or other immigration benefits, often due to fraud, misrepresentation, or other disqualifying reason.

Alternatives to Detention: The collective name given to a group of programs providing for the release of aliens in deportation proceedings, sometimes under a form of supervision such as electronic or telephonic monitoring.

Asylum: Individuals who requested admission based on fear of persecution.

Criminal Alien Program: Identification and processing of aliens who are incarcerated within federal, state, and local prisons and jails.

Fugitive, Mobile, and At-Large Criminal Alien Ops: Programs involving the location and arrest of removable aliens who are not currently incarcerated, including released convicted criminals and those who absconded from criminal and/or immigration proceedings.

HSI Criminal Arrest: Programs targeting gangs, child pornography, human smuggling and trafficking, identity fraud, egregious illegal hiring, and other criminal violations.

Intelligence: Those arrested based on intelligence gathered on illegal trade, travel, and financial activity.

Joint Terrorism Task Force: Arrests resulting from investigations under the auspices of multi-agency task forces focused on detection, dismantling and prosecution of those involved in terrorism or with terrorist organizations.

Juveniles: Individuals classified as a minor at the time of initial arrest, such as unaccompanied minors crossing the border illegally and later removed from the interior.

Local Law Enforcement Area Response Units: Respond to alerts and referrals from local law enforcement agencies.

HSI Investigations: Arrests resulting from HIS investigations, not always targeting criminal aliens, e.g. arrests resulting from worksite investigations.

Quick Response Team: These teams are mobilized in urgent situations, including when other federal, local or state agencies request ICE assistance.

End Notes

1 According to recently released annual statistics from U.S. Customs and Border Protection, most of those apprehended after crossing illegally were family units or unaccompanied minors (600,000 out of 850,000 total apprehensions). Due to legal restrictions, most of these arrivals are released. Only 55,000 were returned to Mexico to await hearings under a new Trump administration program, and the government has the capacity to detain no more than a few thousand in ICE facilities here. That means that several hundred thousand migrants were released into the country for an indefinite period. See "CBP Releases Fiscal Year 2019 Southwest Border Migration Stats", U.S. Customs and Border Protection, October 29, 2019.

2 For more on due process in immigration proceedings and the deportation process, see W.D. Reasoner, "Deportation Basics: How Immigration Enforcement Works (Or Doesn't) in Real Life", Center for Immigration Studies, July 18, 2011.

3 George J. Borjas, et al, "Immigration and the Economic Status of African American Men", in Economica, Volume 77, Issue 306, April 2010.

4 For an explanation of the ICE arrest programs named in Tables 1 and 2, see the appendix.

5 "Local ICE director discusses sanctuary policy impact on public safety", Immigration and Customs Enforcement press release, September 27, 2019.

6 ICE records indicate that about 60 percent of those released by sanctuary policies remain at large and cannot be located. Typically, they are found again when they are arrested for a subsequent crime. See Jessica M. Vaughan, "Rejecting Detainers, Endangering Communities", Center for Immigration Studies, July 13, 2015.

7 Acting ICE Director Tom Homan in remarks in Miami, Fla., as reported by Fox News in "ICE Director: Sanctuaries 'Pulling their own funding' by disobeying feds", August 16, 2017.

8 See "National Gang Unit", U.S. Immigration and Customs Enforcement, last updated June 15, 2017.

9 Jessica M. Vaughan, "Restoring Enforcement of our Immigration Laws", testimony before the U.S. House of Representatives Judiciary Committee, sub-committee on Immigration and Border Security, March 17, 2017.

10 Jessica M. Vaughan, "MS-13 Resurgence: Immigration Enforcement Needed to Take Back Our Streets", Center for Immigration Studies, February 21, 2018.

11 Rachel E. Morgan, Ph.D. and Barbara A. Oudekerk, Ph.D., "Crime Victimization: 2018", U.S. Department of Justice, Bureau of Justice Statistics, NCJ253043, September 2019.

12 See additional data from the National Crime Victimization Survey, here.

13 Lynn Langton, Marcus Berzofsky, Christopher Krebs, and Hope Smiley-McDonald, "Victimizations Not Reported to the Police, 2006-2010", Bureau of Justice Statistics, DATE. Bureau of Justice Statistics report, August 2012.

14 "Evaluation Study of Prince William County's Illegal Immigration Enforcement Policy: FINAL REPORT 2010", Prince William (Va.) County Board of Supervisors, November 2010 .

15 Executive Order, "Enhancing Public Safety in the Interior of the United States", January 25, 2017.

16 See Andrew R. Arthur and Jessica M. Vaughan, "Bill Would Move to Control Gang Violence", Center for Immigration Studies, September 11, 2017.