In a debate last week with CIS Executive Director Mark Krikorian, George Mason University Prof. Bryan Caplan was asked about Milton Friedman's famous dictum, "It's just obvious you can't have free immigration and a welfare state." Caplan responded that although Friedman could be correct if the welfare state were sufficiently large, he is not correct in the context of today's United States:

Now the question is, "How do the numbers actually turn out?" And I say when we go and look at those numbers [from the] National Academies of Sciences, you'll see that Milton Friedman is just plain wrong. The American welfare state is not so large to actually turn immigration into a fiscal burden on Americans. In fact, even low-skilled immigrants, as long they're young, are a net fiscal benefit in the modern United States.

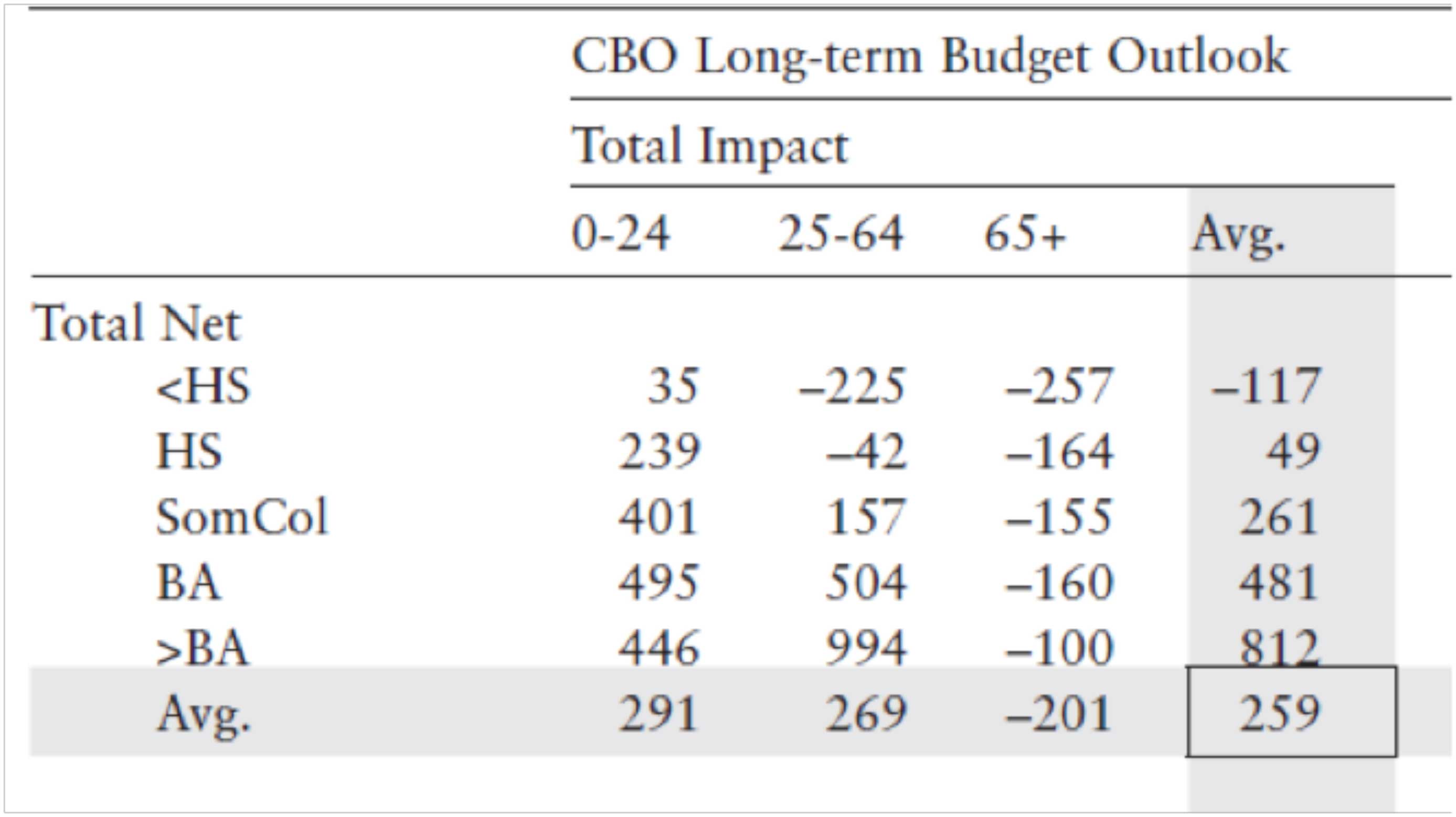

The National Academies did not say that. Puzzled, I consulted the section of Caplan's open-borders book where he discusses this issue. Here is the National Academies' table that he references most often:

|

The table gives the lifetime net fiscal impact of a new immigrant, in thousands of dollars, by education and entry age. Negative numbers mean a cost to taxpayers. For example, a new immigrant who arrived between the ages of 25 and 64 with a high school education (the "HS" row) would impose a lifetime cost of $42,000. (Please note that the results in this table come from just one of many budgetary scenarios contemplated by the National Academies, but I'll focus on this one because it was Caplan's choice.)

Look at the row labeled "<HS", which means a high school dropout. Among dropouts, immigrants in the 25-64 and 65+ age categories are clearly fiscal burdens, as they cost taxpayers $225,000 and $257,000, respectively. Caplan, however, is tantalized by the age 0-24 column, which shows positive $35,000. "Even young high school dropouts more than pull their weight," he concludes.

That conclusion is based on a misunderstanding of the table. Among immigrants in the age 25-64 and 65-plus columns, the education rows refer to the education of the immigrants themselves. However, in the age 0-24 column, education refers to the education of the immigrants' parents. As p. 464 of the National Academies' report explains, "If the immigrant arrives before age 25, we instead predict a future education level ... based on parental education." The reason the fiscal impact appears positive is that the model assumes that the children of high school dropouts will get more education than their parents did. In other words, most of Caplan's "young high school dropouts" are not dropouts at all.

This is an understandable mistake, as the National Academies authors should have been clearer that the age 0-24 column has a different interpretation than the other two age columns. Nevertheless, Caplan's misinterpretation has led him far astray. Although the National Academies did not publish fiscal estimates for under-25 immigrants without a high school diploma, a separate calculation in Table 8-13 found that a high school dropout immigrant who arrives at the age of 25 will generate a lifetime fiscal cost of $186,000. That cost stands in stark contrast to Caplan's claim that "Even young high school dropouts more than pull their weight." They don't.