Download a pdf of this Backgrounder

David North is a CIS fellow who has studied the interaction of immigration and U.S. labor markets for more than 30 years.

There have been numerous recent proposals to increase the admission of skilled workers from abroad. This paper examines some of the issues surrounding the question of skilled immigration. The findings include:

- There are about 10 million Americans with STEM degrees (Science, Technology, Engineering, and Mathematics) not working in those fields.

- Each year, some 200,000 additional skilled foreign workers are admitted through a variety of existing visa programs.

- At least one million skilled nonimmigrant workers are in the United States at any one time.

- The large majority of foreign PhD recipients already remain in the United States under current law.

The forces of big industry and big immigration beseech us to change our immigration laws to permit the admission of more skilled immigrants; we must seek the help of the world’s “best and brightest,” they say. What is never mentioned is that “the best and the brightest” are already here. Further, close to 200,000 additional skilled migrants routinely enter the nation each and every year without any new laws. Year after year.

Yes, it is gratifying that really able people from all over the world want to come to the United States to work, study, start new companies, and in some cases, get rich. But that is happening all the time, anyway, and there is no need to change our laws to encourage these trends.

But no one notices that.

Further, there seems to be this underlying notion — never expressed — that the “best and the brightest” are good at matters technological, but dolts when it comes to matters practical.

Yes, they may be PhDs in information technology, and valedictorians and salutatorians, but can they figure out how to cope with our easy-to-manipulate immigration system? Of course not! They must be given additional laws and incentives and new kinds of visas must be created for them, or else, the implication is, they will work for peanuts in China or India, and their brilliance will never shine in the United States. I find that unlikely.

In order to get a little perspective on these matters, let’s look briefly at four topics:

- The current supply of, and demand for, skilled labor in the United States;

- The continuing massive inflows of skilled labor from abroad, both permanent and more or less temporary, and the degree to which these workers stay here;

- The impacts of these flows on job opportunities for U.S. residents and the American economy, generally; and

- How the open-borders advocates seek to use the “best and brightest” argument to open the floodgates for many more plain-vanilla foreign workers.

Supply and Demand

Ignoring for the moment the self-serving anecdotes of both industry and the unemployed, let’s turn to readily available, non-self-serving public data on this subject.

I suggest this approach because it is equally hard to evaluate the significance of either a business executive saying that he cannot hire, say, a PhD in chemical engineering at $85,000 a year, or a resident PhD in that field saying that he is well qualified, but unemployed. The offered job may require, for instance, a very narrow specialty, the employer may insist that the new worker be under 30 (which is, of course, illegal), and it turns out the job is in Fargo, N.D. (which is perfectly legal). The resident PhD, on the other hand, may look good on paper, but turn out to be a bad fit for team-research activities. Better that we use other, more reliable measures of demand and supply than such anecdotes.

There are numerous indications in the high-tech fields that there is a surplus of both domestic and potential foreign workers in the U.S. labor markets. If a firm is hiring at the bachelor’s level, the Bureau of Labor Statistics tells us that in June 20111 there were 2,118,000 unemployed residents of the United States with bachelor’s degrees or more. There are some duds in that group, undoubtedly, but a lot of skills as well.

Another way of looking at this situation is to examine what America’s colleges and universities are doing to produce graduates in the STEM (Science, Technology, Engineering, and Mathematics) fields and to compare that to the STEM workforce, as Hal Salzman, a professor of public policy at Rutgers has done.

Salzman puts the total STEM workforce at 4.8 million. That is roughly one-third of the 15.7 million workers who hold at least one science or engineering degree.

There are a lot of skilled workers who have been lured out of the not-very-well-paid STEM occupations to work in high finance and elsewhere, and he suggests that an increase in wages would bring many back into STEM activities.2

Supposing the employer — and many of them operate this way — would prefer to ignore the two million-plus unemployed graduates in the country, and ignore the 10 million or so STEM-trained people employed outside STEM occupations, and wants to hire foreign workers. Well, there are plenty of opportunities to do that through, for instance, the numerically limited aspects of the H-1B program. Of the 85,000 numerically limited slots in that program for the coming fiscal year 57,900 of them remained open on June 17, 2011, according to U.S. Citizenship and Immigration Services (USCIS).3

In addition there are numerically unlimited opportunities to hire skilled foreign labor in the L, J, O, and F-1 (with OPT) categories that are described below. In the last-named category the employer gets a bonus of as much as $10,000 for hiring a foreign graduate of an American university rather than a citizen or a green card graduate of the same university with the same skills.4 That may be hard to believe, but it is the case.

Do these macro indications show a need to import more foreign workers than we already do? I do not think so, but first let’s look a little further at the current and prospective inflows of foreign skilled workers under existing laws.

Current Inflows

The flows of foreign workers come in two different, but related, channels. There is the larger flow of more or less temporary workers in the nonimmigrant stream, and then there is the granting to a smaller group the status of permanent resident alien (PRA) held by people with green cards. While most nonimmigrant arrivals are, in fact, arrivals from abroad, the grants of PRA status are usually, but not always, to people who have been in this country for years as nonimmigrants.

Nonimmigrants. There are multitudinous visa categories that can be used by skilled foreign workers, but we are going to concentrate on only five of them: F-1, J-1, L-1, H-1B, and O-1 statuses; all of the people in the last four of these visa classes can work full-time legally in the United States, and some of the F-1s can as well. There are many other classes of nonimmigrant workers,5 but these five contain most of the skilled ones.

Of the five categories, only the H-1B workers are admitted against numerical ceilings; there are no numerical limits for the others. To provide one very rough measure of the size of the flows of these five groups, we use the number of admissions6 in FY 2009. Those counted are only the workers or worker-students, and none of their dependents. All numbers are rounded to the nearest thousand.

| Nonimmigrant Visa Class | FY ‘09 Admissions |

| F-1 (students) | 895,000 |

| J-1 (exchange visitors) | 413,000 |

| H-1B (tech workers) | 339,000 |

| L-1 (intracompany transfers) | 333,000 |

| O-1 (extraordinary ability) | 46,000 |

| Total admissions | 2,026,000 |

Most of the F-1s and many of the J-1s are not available for commercial work, being occupied at academic institutions. Some of the J-1s, particularly the youngsters in the summer work travel program, are not skilled workers. Virtually all of the H-1Bs and L-1s are college graduate workers or managers; the O-1 visa holders include people prominent in science, business, academia, and athletics, but not in the arts or entertainment.

An F-1 worker who has completed a degree has 29 months afterward during which he or she can work, provided the graduate is in one of a long list of academic specialties;7 it is during this period that the alien graduate’s employer receives a bonus because the employer need not pay payroll taxes.

The O-1 category is interesting, in that a person whose talents are recognized can nominate himself or herself for a visa, but there must be some indication that an agent or an employer will be involved in the alien’s trip to the United States. The requirements for extraordinary abilities seem to be rather demanding. USCIS is in the throes of streamlining the application process to make it less burdensome on the applicant. The initial visa can be as long as three years and it can be extended if USCIS agrees.

What is described above is a menu written in bureaucratese about some of the routes a talented, or at least an educated, alien can use to get into the United States and get a job. These routes are taken frequently by both the “best and the brightest” and by much larger numbers of less distinguished workers.

The size of these nonimmigrant worker populations — a subject never raised by the mass migration advocates or government officials — is remarkable. By population, I mean the number of people with these visas in the country, and in the labor market, at any specific point of time, known as the “stock.” (This is a different concept from the admission figures noted above, which measure the “flow,” to use the demographer’s term.)

The two largest of these populations have been estimated as follows:

| H-1B | 650,0008 |

| L-1 | 350,0009 |

| Total | 1,000,00 |

The other groupings (F-1/OPT, J-1, and O-1) may only add another 100,000 or so to the nonimmigrant skilled worker population, perhaps cancelling out the fact that some of the H-1Bs are teachers and a few are fashion models, and some of the L-1s are managers.

The major point is that there is a thunderous number of foreign workers with at least bachelor’s degree in the nation as nonimmigrants at any given time, most with tech backgrounds.

And they keep coming.

Let’s look at the annual additions of skilled nonimmigrant workers to our work force, as distinct from the less helpful admissions numbers shown above. What the open-borders types want to do is to enlarge the number of annual additions to the skilled work force by changing the migration rules. Let’s look at how many additions we are getting each year, anyway, under current laws — additions, I should note, to an already ample stock of such workers.

My estimate of these annual additions, under current law, averages at least 200,000 a year. There are three main components of this estimate: additional H-1B workers, additional L-1 workers, and all other nonimmigrant workers (F-1 with OPT, J-1, and O-1). Since the 85,000 ceilings for H-1B applications are routinely filled each year — though we are not there yet with the next fiscal year — and since there are no limits to H-1Bs hired by academic institutions (let’s call that 15,000 a year for convenience) we receive an additional 100,000 H-1B workers annually.

Professor Hira has estimated annual additions of L-1s at 75,000 a year.10 And I suspect that the other categories add another 25,000 each year.

Immigrants. Ignoring, for the moment, the numerous skilled alien workers who secure PRA status through the family, refugee, asylee, and diversity visa routes, notably the ones who marry into green card status, let’s look at the number of skilled workers who are granted green card status every year, because they are skilled workers.

As noted earlier, most of these are not new arrivals, most being former nonimmigrant workers who have opted to stay in the United States, and who have found an employer who wants them to stay. Their conversion to PRA status (“adjustment” is the government’s word) is another indication of the existing welcome that the United States has for skilled workers.

The immigrants of interest come in several subcategories within the employment-based preferences:

- First Priority: aliens with extraordinary ability, such as outstanding professors or researchers and multi-national corporate executives;

- Second Priority: professionals with advanced degrees or aliens of exceptional ability; and

- Third Priority: professionals with baccalaureate degrees.

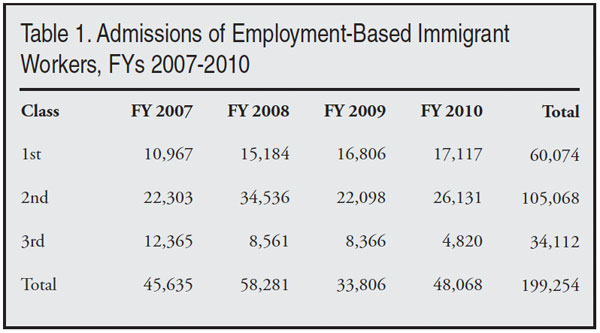

Table 1 shows the admission figures for the last four years in the categories as I have defined them. (Admission/adjustment figures for immigrants are once-in-a-lifetime numbers, and are more useful than admission data for nonimmigrants.) The numbers below are for workers only, and do not include their dependents, who are admitted (or adjusted) at the same time as the workers.

There is clearly a discontinuity between my estimate of about 200,000 highly skilled workers arriving as nonimmigrants each year, and my estimate of about 50,000 of them securing PRA status.

Why this gap? Some of this may relate to matters of definition. (Nonimmigrant categories and immigrant categories do not mesh neatly). Further, parts of the gap may be explained by each of these factors:

- alien workers dying in the United States, but that’s only a handful;

- such workers having gone to a third country;11 or

- having obtained a green card by others means, such as marriage; or

- having returned home; or

- having obtained another kind of temporary work visa (such as A or G);12 or

- having slipped into illegal status.

By far the most likely scenario, not listed above, is that they are waiting in legal nonimmigrant status in the United States to move into green card status. Some are waiting for an employer to file initial labor certification papers for them, others (with those in hand) are waiting for visas, the second step in the process.

The second kind of wait is much longer for people from just two countries, China, and even more so, India. This is the case because of the interplay of two sets of numerical ceilings laid on by Congress. There are numerical limitations on each class within the employment-based group, and, in addition, no more than seven percent of all the numerically limited immigrants in a given year can come from a single nation.13

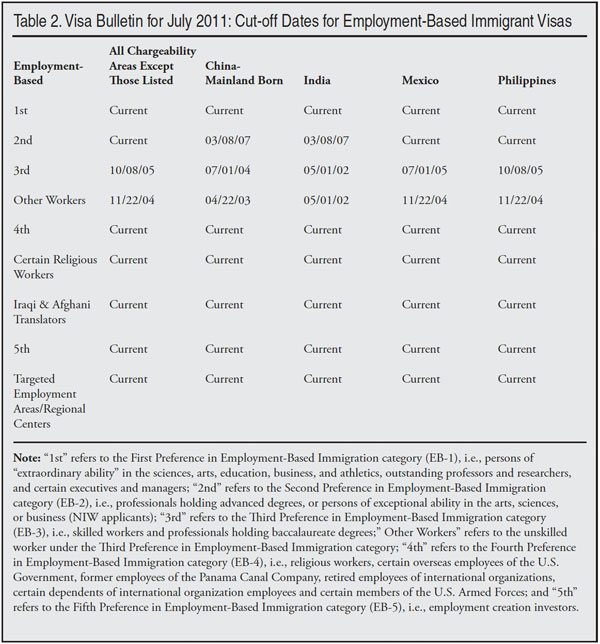

Every month the Visa Office publishes the Visa Bulletin, with a portion of the July 2011 issue seen here as Table 2. It displays the current interplay among the various numerical ceilings and flows of applications.

What is interesting here, and rarely discussed by migration advocates, is that this complex system works strongly in favor of elite categories of would-be immigrants, and thus for the “best and brightest.” Note in the table that the situation is “current” involving no waiting for any First Preference applicants, and that except for India and China, there is no waiting for the Second Preference applicants, the ones with “advanced degrees or persons of exceptional ability.” The third preference, which one can secure with a bachelor’s degree, is heavily backlogged throughout the world, as are some of the family categories not shown in this table.

High-tech workers with H-1B visas can obtain extensions of their visas forever as long as they have an approved — but not yet ripe — green card application. Do high tech workers in this situation wait for their visas? Does the United States retain such people? That’s the next question.

Retention Rates. One of the arguments some advocates use for expanded immigration is that we should be granting automatic green cards to aliens who complete high-tech advanced degrees in the United States, rather than forcing them into the waiting game described above.

To what extent are we holding on to foreign talent under our current set of laws and regulations?

Fortunately one man has been studying that question for decades using a solid database14 and strong institutional support. He is Michael Finn of Oak Ridge Laboratories, a federal institution.

The population he follows consists of aliens receiving PhDs in the United States. His most recent report,15 in 2010, showed that 67 percent of foreign PhDs graduating in 2005 were still in the United States two years later. Interestingly, we tend to keep the ones that Silicon Valley is most interested in and lose most of those in other fields. Finn found that, five years after graduation, 72 percent of the computer science graduates were still here, but only 42 percent of the economists remained.

In summary, we have a massive population of foreign-born and often U.S.-trained highly skilled workers, certainly one million in just two nonimmigrant categories; we add 200,000 or so new skilled alien workers each year, and we are retaining large proportions of them. Do we need to add to this population and to augment the existing flows?

Impact on U.S. Systems

Clearly these massive movements of skilled workers have had substantial impacts on the American economy and its labor force; these impacts are multitudinous and have been widely debated.16

Industry advocates have argued that there is a shortage of scientific talent in the United States, and therefore there is a need to bring still more in from overseas; they stress what they see as the need to encourage the migration of the “best and the brightest” and say that a remarkable amount of innovation and economic opportunity has been produced by migrating high tech workers.

Critics have pointed out how both the size of these programs and the minimal labor market protections within them have shouldered U.S.-resident workers out of high-tech jobs, lowered wages in the industry, and, indirectly, discouraged resident workers studying in, and working in, these fields. I agree with the critics.

This is an important debate, one that cannot be neatly summarized in these pages. Let me, instead, add a footnote to this dialogue, relying on someone who knows these worker migration programs very well.

She is Rep. Zoe Lofgren (D-Calif.), member from Silicon Valley, former chair of the House of Representatives’ immigration subcommittee, and a former immigration lawyer. She currently is the ranking minority member of that subcommittee and is active in its deliberations.

She has, this summer, introduced legislation aimed at expanding the number of green cards available to foreign tech workers, specifically those with advanced degrees (meaning mostly master’s degrees) from recognized American academic institutions. She also advocates additional green cards for foreign entrepreneurs who lack their own capital. Her press release supporting the bill contains the following statement:

“More than 52 percent of Silicon Valley startups were founded or co-founded by immigrants and immigrant-founded companies produced $52 billion in sales and employed 450,000 workers in 2005. Immigration has historically made our economy stronger.”17

Let’s assume, at least for the moment, that all these happy boxcar numbers are all correct.

What she did not say, and probably will not say, is that all of this innovation, and all of this economic activity, was created under the current set of immigration laws.

So why change the laws? Or more pertinently, why change them in the direction of more migration?

“Best and the Brightest”

Formerly, the mass migration advocates (industry division) pressed for larger and larger H-1B ceilings; currently the limit is 65,000 new visas under one provision of the law, and 20,000 new ones under another.18 In earlier years the limits were much higher. There never have been any numerical limits for renewals of these visas.

In recent years, the industry has changed its tune and is now seeking additional green cards (rather than “temporary” visas) for high-tech workers. My sense is that the industry and its numerous lobbyists decided that it would be easier to sell additional immigrants than to sell additional more-or-less indentured workers.

But to use a musical metaphor, the proposal is not a violin solo, it is a full symphony orchestra, playing many themes and variations all at the same time. In order to recruit a few of the “best and the brightest,” the Lofgren bill would make the following changes to our immigration laws:

- It would grant automatic green cards to aliens getting advanced degrees at a wide range of U.S. academic institutions that do at least some research;

- These green cards would be available outside the 140,000 ceiling for employment-based workers;

- In addition, dependents of some of these new green card holders would not count against the 140,000 limit, unlike dependents of other workers admitted for their skills;

- Still further, it would eliminate existing employment-based per-country limits;

- It would create a brand new class of alien entrepreneurs who would need to raise $500,000 of someone else’s money for start-up businesses; and

- These, too, would be admitted, after a conditional period, outside the 140,000 limit.19

Other advocates have added still other ideas, such as allowing H-1B aliens who start their own firms to then use those firms to create green cards for the founder-owners, in what I call the “I am my own grandpa” scheme.

The only proposal in this field that I have seen that would not create more immigrant slots was proposed by immigration attorney Angelo Paparelli. He noted that some of the Indians and Chinese waiting for their H-1B visas to flower into green cards had a special problem; the waiting times were long enough so that some children of the main applicants would pass their 21st birthday, and thus “age out” of eligibility. To fix that he would freeze their eligibility at the time of the filing of the application, rather than at the time of its being granted. I do not mind that idea because it keeps migration within the current numerical limits.20

It is obvious, once one starts looking at the details of these schemes, that they will all bring in great numbers of pretty ordinary workers and spouses and kids (some of the latter over 21) along with the occasional innovative genius.

Further, as one looks over these various schemes, one notices something missing. Legislation on immigration, and on all sorts of other topics, is generated in Washington where horse-trading and negotiated settlements are par for the course. What I find interesting is that no one who is pushing the “best and the brightest” schemes has thought to link one of their proposals to an immigration-diminishing proposal at the lower end of the education scale.

Why not propose to reduce the 50,000 diversity visas by 1,000 or so for every additional 100 high tech workers? That’s an idea that might fly!

The diversity visas, or lottery visas, lead to green cards for aliens who have no skills beyond a high school education (and their immediate relatives), aliens who have not been requested by an American employer, and who have no relatives in this country, i.e., a group who would never get a visa under any other circumstances.21 Why not start whittling away at those numbers?

End Notes

1 See “Employment status of the civilian population 25 year and over by educational attainment”, BLS, Washington, DC, 2011, http://www.bls.gov/news.release/empsit.t04.htm.

2 See Alan S. Brown, “What Engineering Shortage?” The Bent of Tau Beta Pi, Knoxville, Tenn., Summer 2009, p. 22, http://www.tbp.org/pages/publications/Bent/Features/Su09Brown.pdf.

3 See USCIS notice “H-1B Fiscal Year (FY) Cap Season” at http://www.uscis.gov/portal/site/uscis/menuitem.5af9bb95919f35e66f614176....

4 The bonus to the employer is caused by the fact that hiring these foreign graduates will exempt the firm from paying the normal payroll taxes for 29 months; this comes from the power of the Immigration and Customs Enforcement to regulate the work activities of foreign students after they graduate and are in the Optional Practical Training phase of their F-1 status. Workers with F-1 visas, and their employers, are shielded from payroll taxes, such as FICA and Medicare. For more on this see my blog of May 13, 2011, “DHS Raids Social Security System and Zaps U.S. Workers - Again” at http://www.cis.org/north/expanded-OPT-stem-list; and the ICE announcement with its totally misleading headline: “ICE announces expanded list of science, technology, engineering and math degree programs / Qualifies eligible graduates to extend their post-graduate training” at http://content.govdelivery.com/bulletins/gd/USDHSICE-7434c. The ICE announcement headline sounds like it is related to graduate study programs, rather than to an enlarged, subsidized, nonimmigrant worker program.

5 Among the other categories are the NAFTA visas given to Canadians and, to a much lesser extent, Mexicans with college-level skills.

6 Admissions data are useful because they, unlike some other data, are immediately available, but they relate to the passage of aliens through ports of entry, rather than population counts; one nonimmigrant worker might enter the nation just once in a period of five years, and thus be counted only once, while another might do so several times a year, and thus be counted as an additional admission each time. (While most DHS data is available for FY 2010, the latest nonimmigrant admissions data are for the prior year.) All numbers come from DHS Office of Immigration Statistics 2009 Yearbook of Immigration Statistics, Table 25.

7 For the government’s full list (many pages long) of these academic specialties, see http://www.ice.gov/doclib/sevis/pdf/stemlist2011.pdf.

8 See my H-1B population estimate at http://cis.org/estimating-h1b-population-2-11.

9 See the L-1 population estimate of Ron Hira, Associate Professor of Public Policy, Rochester Institute of Technology, at the Industry Studies Association meeting in Pittsburgh, June 1, 2011, at http://www.industrystudies.pitt.edu/pittsburgh11/documents/Presentations... percent20Presentations/2-6 percent20Hira.pdf.

10 Ibid.

11 At one point recently the oil-rich Province of Alberta was actively recruiting people with H-1B credentials from within the United States. In Canada provinces have a greater role in the immigration process than states do here. For more on Alberta’s outreach to H-1Bs, see http://www.cicnews.com/2009/05/h1bfasttrackcanadianimmigrationcategory05....

12 There probably are only minimal flows along these lines. A visas are for diplomats and G visas are for international civil servants, working for institutions such as the World Bank or the International Monetary Fund; the World Bank, at least, employs engineers and scientists and offers them excellent salaries and remarkable tax benefits.

13 See Section A2 of the State Department’s Visa Bulletin, at http://www.travel.state.gov/visa/bulletin/bulletin_5489.html.

14 Dr. Finn has the Social Security numbers of all the members of each cohort of the aliens with new PhDs, and he has access to annual earnings data for them.

15 Michael Finn “Stay Rates of Foreign Doctorate Recipients from U.S. Universities, 2007”, Oak Ridge Institute for Science and Education, Oak Ridge, Tenn., 2010, the summary of which can be seen at http://orise.orau.gov/media-center/news-releases/2010/fy10-20.aspx.

16 For more on the adverse effects of the H-1B program see the writings of Ron Hira of the Rochester Institute of Technology, http://www.rit.edu/news/experts.php?action=viewexpert&id=139; John Miano of the Center for Immigration Studies, http://cis.org/Miano; and Norm Matloff of UC-Davis, http://heather.cs.ucdavis.edu/h1b.html. For a statement arguing in the other direction from Microsoft Chairman Bill Gates before a congressional committee, see http://www.avlawoffice.com/BillGatesstatement.htm.

17 As quoted in Patrick Thibodeau, “Democrats seek major H-1B, green card reform”, Computerworld, June 15, 2011, http://www.computerworld.com/s/article/9217628/Democrats_seek_major_H_1B....

18 The 65,000 new H-1B visas a year are for general commercial use; the 20,000 new visas limit is for aliens with advanced U.S. degrees (usually a master’s degree); and academic institutions can hire as many new ones as they want, without regard to any ceiling.

19 See the full text of Rep. Lofgren’s HR 2616 at http://www.govtrack.us/congress/billtext.xpd?bill=h112-2161 and for a report on it, see

http://thestockmarketwatch.com/stock-market-news/recent-events/high-skil....

20 For more on Paparelli’s creative ideas (including the grandpa scheme), see my blog at

http://www.cis.org/north/paparelli-proposals.

21 For the government’s description of this program, see http://www.uscis.gov/portal/site/uscis/menuitem.eb1d4c2a3e5b9ac89243c6a7....