Download a pdf of this Backgrounder

George W. Grayson, a CIS board member, is the Class of 1938 Professor of Government Emeritus at the College of William & Mary; his latest book, co-authored with Samuel Logan, is The Executioner's Men: Los Zetas, Rogue Soldiers, Criminal Entrepreneurs, and the Shadow State They Created (Transaction: 2012); 757-253-2400; 757-810-0034; [email protected].

Introduction

The hijinks of Mexico's state governors often prove more titillating, suspenseful, and eye-popping than Univisión soap operas. Sergio Estrada Cajigal, the chief executive of Morelos (2000-06), wowed Cuernavaca's citizens by taking sexy girlfriends on flying trysts in a helicopter. Estrada and his successor rented the so-called helicóptero del amor at a cost of $172,500 to taxpayers.1 Then there is Oaxaca's José Murat Casab, who in March 2004 claimed to have been targeted by gunmen. His account of the event was "full of more holes than the vehicle that was purportedly sprayed by shooters with Kalashnikov assault rifles."2 Critics say the swaggering cacique staged the phony shoot-out to loft his sagging approval ratings. In terms of chutzpah, however, it's difficult to top Tabasco's former chief executive Andrés Granier Melo (2006-12), who bragged in a recorded conversation that in forays to Fifth Avenue and Rodeo Drive, he had purchased 400 pairs of pants, 300 suits, 1,000 shirts, and 400 pairs of shoes — with footwear costing $650 or more. How strange that he could not account for the "disappearance" of 900 million pesos ($69.3 million) at the same time that his family's bank accounts got fatter and fatter.3

From 1997 to 2012, an executive-legislative deadlock impeded decision-making by Mexico's national government. Like nature, politics abhors a vacuum. Several groups filled the political void: Televisa, TV Azteca, and other media networks, multinational corporations, drug cartels, and venal boss-ridden labor organizations such as the Oil Workers Union (STPRM), the National Syndicate of Educational Workers (SNTE), and the radical National Coordinator of Education Workers (CNTE), which invaded Mexico City in September with 20,000 firebrands. Until the late-20th century, the nation's 31 governors, the mayor of Mexico City, and many of the 2,435 municipal presidents typically played second fiddle to the president, finance and government secretaries,4 and key legislators. The stalemate, which began in 1997, transformed them from vassals to barons of their fiefdoms. Analyst Luis Rubio astutely observed that "Mexico is the only country that has evolved from a monarchy to feudalism."5

State executives may argue over abortion laws, the pros and cons of DF (Mexico City) statehood, and the legalization of marijuana in their bailiwicks. However, they agree completely on the importance of a generous immigration reform by U.S. decision-makers. At a meeting of Mexico's National Commission of Governors (CONAGO), Eruviel Ávila Villegas, Mexico State's chief executive and the group's foreign affairs spokesman, emphasized the importance of the pending legislation. He stressed that "we must directly strengthen our international cooperation with governments and social organizations" in concert with the Ministry of Foreign Affairs (SRE).6 At the same time, the state leaders agree with Chihuahua's free-spending Governor César Duarte Jáquez that the construction of a new wall between Mexico and the United States would be an "aberration", even as his own country gropes for an effective deterrent to Central Americans and other foreigners crossing Mexico through Guatemala and Belize.7

This Backgrounder (1) analyzes the windfall that state and local officials receive from remittances of Mexicans living abroad; (2) illustrates the irresponsible and illegal actions of state executives who receive 90 percent of their budgets from the federal government, even as they spurn using the taxing powers at their disposal; and (3) highlights the formal and informal powers exercised by the new viceroys.

I. Windfall from Remittances

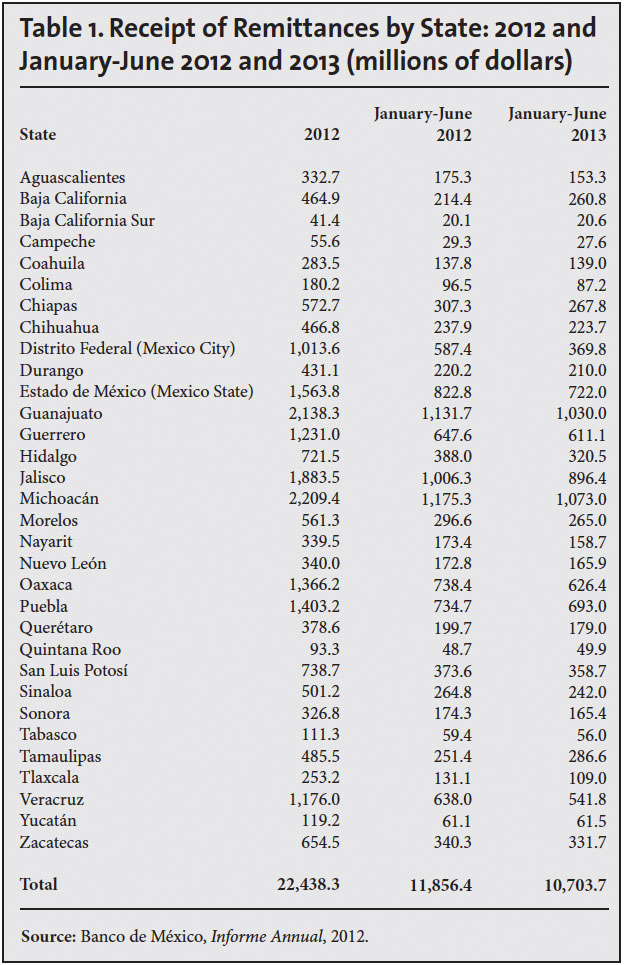

During the first six months of 2013, the influx of dollars from abroad dropped 10.77 percent, which reflected sluggish growth in both Mexico and the United States. Nonetheless, the $10.7 billion influx from abroad allowed states to reduce outlays on education, health care, housing, nutrition, roads, bridges, environmental protection, and public safety for their citizens, many of whom live in hardscrabble poverty. Needless to say, they do not assess property and irrigated fields at the market value, and nine times out of 10 do not collect these taxes in order to ingratiate themselves with powerful and affluent supporters. Table 1 indicates the remittances received in the first halves of 2012 and 2013.

II. Irresponsible Behavior

The access to remittances frees up monies that allow governors to engage in a bizarre and irresponsible manner, even as they seek additional funds from Mexico City.8 One of their favorite pasttimes is flying hither and yon without accounting for their expenditure and objectives.

If they cashed in their frequent flyer miles, governors could slash their mounting debts. Table 2 is a sampling of jet-setting by state executives who justify their spendthrift forays on the grounds that they are promoting investment and trade. If the benefits of what appeared to be boondoggles were revealed, an informed public might conclude that their excursions were justified. In only a few instances are there public disclosures — and then it's often because an enterprising journalist or politician has blown the whistle on the junket. PRI legislator Bárbara Botello Santibáñez harrumphed that: "[Guanajuato Governor Oliva Ramírez] seems to be wasting money; he never informs us of the results of his trips, never discloses an agenda of the places visited; and, even worse, he speaks of attracting investments that . . . do not materialize." The PAN's Oliva Ramírez also proposed doling out $3.25 million for a statue to celebrate the bicentennial of the nation's independence.9

Ramírez could not match the 341-foot-tall Estela de Luz ("Column of Light") tower that the federal government constructed for the 200th anniversary event. At the groundbreaking, President Felipe Calderón praised the obelisk as "a symbol of a new era . . . that will illuminate future generations of Mexicans." Unfortunately the structure, erected in Chapultepec Park, opened 460 days late, wound up costing more than twice the anticipated price of 393 million pesos, and required 400 modifications.10

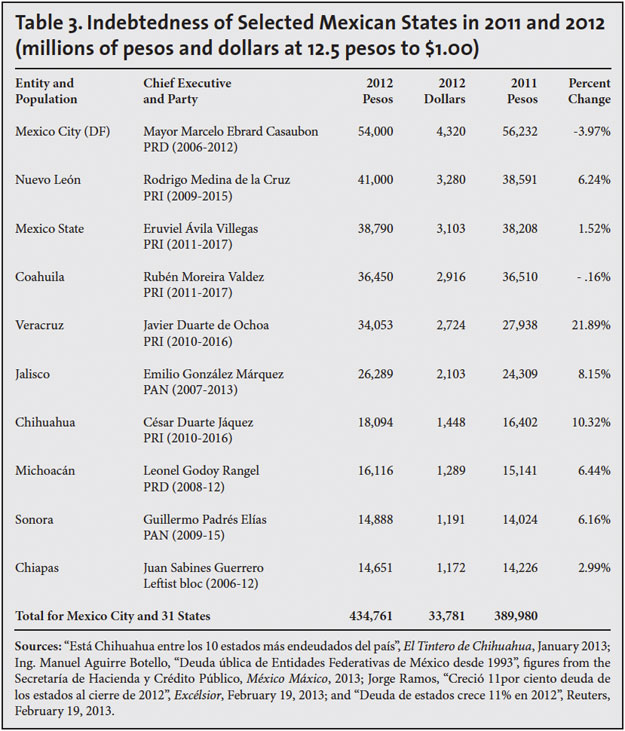

Members of Congress tend to yawn when governors run-up incredibly large deficits. During the Calderón administration, state indebtedness shot up 11 percent to 434,761 million pesos ($33,780 million), according to the Finance Ministry.11 This shortfall equaled roughly 2.9 percent of gross domestic product — an upswing of 43,984 million pesos ($3,518,720) over 2011 with Tabasco (66.3 percent) and Zacatecas (43.5 percent) leading the pack. Senator Raúl Morón Orozco proposed on behalf of the leftist-nationalist Democratic Revolutionary Party (PRD) that the federal government soak up the red ink that sloshed across the ledgers of the 10 most indebted states in 2011 and 2012.

III. Formal and Informal Powers

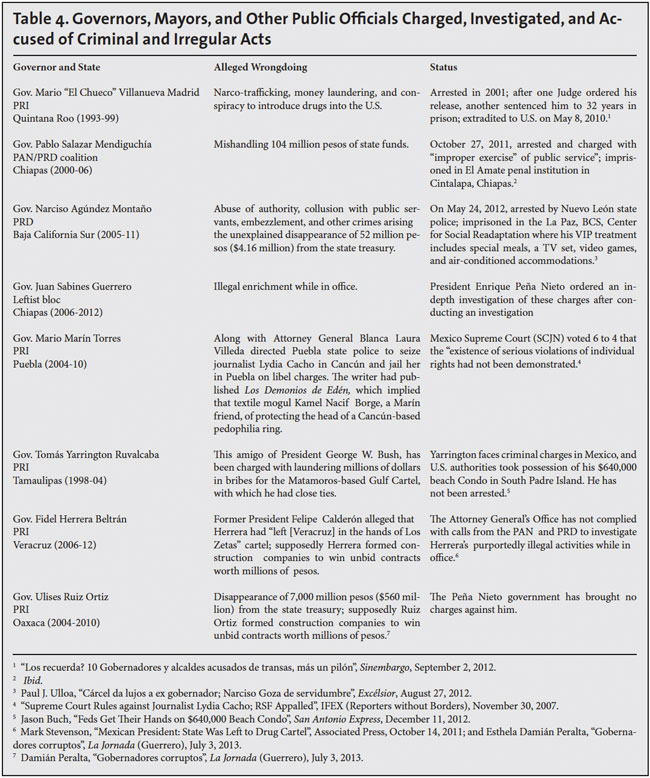

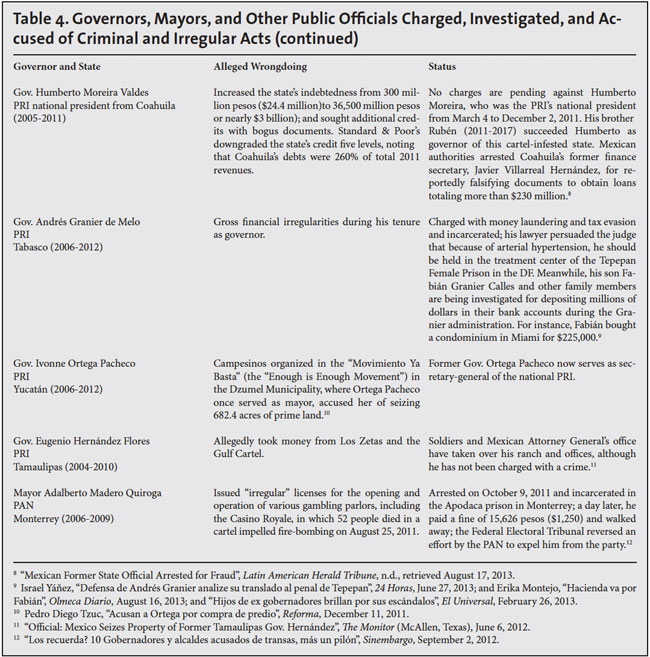

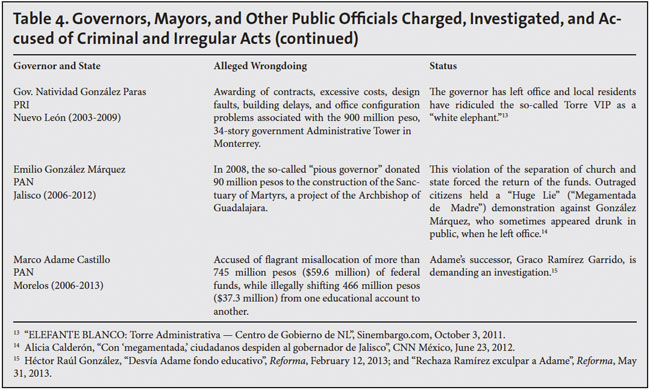

Governors and mayors fatten their bank accounts, engage in sweetheart contracts with their own companies for state projects, jet around the world and stay at luxurious resorts, and satisfy their creature comforts because of the impunity they enjoy. National and international media shed some light on irresponsible federal officials, but governors, mayors, and their underlings tend to run their states like viceroys of the colonial period. Several factors contribute to their enviable and lucrative status.

The federal Congress lavishes money on the states, which obviates governors' imposing taxes that are available to them. It is unusual for a state to generate more than 10 percent of the income that it spends; in 2013, the federal government provided upwards of 95 percent of the finances of state and municipalities.12

The majority of governors belong to the Institutional Revolutionary Party (PRI), which ran the country in Tammany Hall-fashion from 1929 to 2000. When nominees of the center-right National Action Party (PAN) twice captured the presidency — Vicente Fox Quesada (2000-06) and Felipe Calderón Hinojosa (2006-2012) — the governors thought they had died and gone to heaven. Unlike the days of PRI hegemony, they no longer feared being summoned to Mexico City for a tongue-lashing, dismissal, or instructions on whom to back as their successors. They also spent money like water. Municipalities and states, which typically assess property, including land and water, at absurdly low rates, often collect only a pittance of taxes due, if any at all.

The failure of state and municipal executives to indicate how they spend federal funds spurred the Finance Ministry (SHCP) to seek legislation directing states to earmark monies for specific purposes, ban transfers of resources to other activities, and require accountability of outlays. Legislators, especially PRI deputies eager to propitiate their party's 20 governors, assigned this measure to the deepfreeze.

Of course, the Chamber of Deputies is hardly in a position to preach frugality.13 In addition to their normal salaries ($6,113/month), deputies receive a Christmas bonus (Aguinaldo; $8,151); funds for legislative assistance ($3,715/month); resources for constituent service ($2,334/month); money to buy Christmas presents ($380); MetLife health insurance for themselves and their families ($1,477/year); compensation of off-set income tax payments ($3,035/year in 2007); contributions to a savings fund ($758/month); funeral expenses for deputies and close family members ($6,113); free airline tickets to return to their home state each week; low-interest loans up to $32,453; mini IPads at costs ranging from $415.92 to $815.92; the 45 committee chairs and secretaries are allotted an extra stipend as well as funds to hire five staff members; deputies receive new cars to replace one-year old vehicles, and party leaders have monies to use as they see fit (e.g., PRI received $39.4 million in 2013). One can identify deputies by their 14-carat gold lapel pins, which collectively cost $130,000. In contrast, the lapel pins worn by member of the U.S. House of Representatives cost approximately $15.14

The auditing of these expenditures is more fiction than fact, and the Supreme Court, whose members receive $320,016 annually, ruled that deputies did not have to reveal their wealth.15

Especially generous to his Senate colleagues was the PAN's parliamentary coordinator Ernesto Cordero Arroyo. On June 10, 2013, he deposited 430,000 pesos ($34,400) from his discretionary funds into the private bank accounts of the party's 37 senators to use for unspecified administrative costs. Erstwhile Finance Secretary Cordero is the unofficial ambassador of to the divided PAN of his former boss, President Felipe Calderón (2006-2012), who is spending a year at Harvard University's Kennedy School. Cordero's closeness to the ex-chief executive has raised the hackles of party president Gustavo Madero Muñoz, who replaced Cordero as the PAN's senate leader after the windfall became public. The embarrassment forced 19 PAN senators to return the largesse; however, 13 of their colleagues, who collectively received 5.6 million pesos ($448,000) have yet to follow suit.16

Cordero antagonist Senator Javier Corral Jurado claimed that the former party leader had also forked over 350,000 ($28,000) to panista senators for legislative aides, constituent service, meals on days without sessions, travel funds, and other questionable items for which there was no accounting.17

For his part, Peña Nieto has not cut corners when it comes to spending on himself, his entourage, and goods and services at Los Pinos. Contracts for services for the incumbent climbed to 646,292,870 pesos ($51,703,343) compared with Calderón's outlays of 80,153,250 pesos ($6,412,260) during his last year in office. While disbursements for food for presidential personnel totaled 3.9 million pesos ($312,000) in 2012, his successor budgeted 6.7 million pesos ($536,000) for this category. IFAI discovered that even the cost of Peña Nieto's official photograph ($29,733) was 60 percent higher than that of his predecessor, who, Priístas claim, was less photogenic.18 In all fairness, an administration's expenditures during the first months in office are invariably higher than in later years.

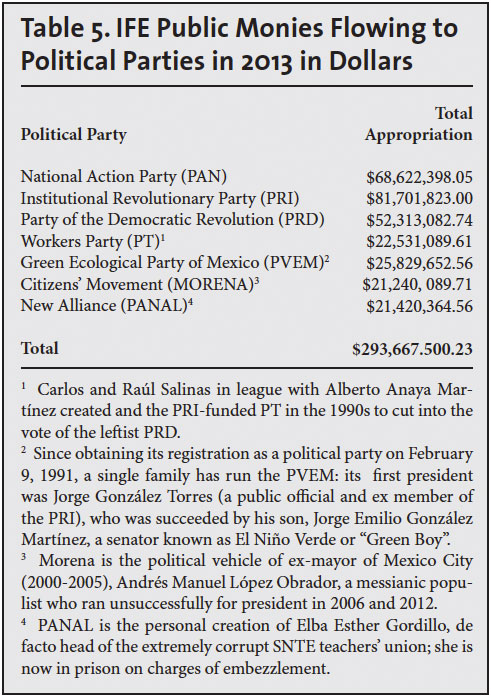

As alluded to, IFE lavishes monies on political parties — to the tune of $293,667,500 in 2013 — with only rhetorical accountability.19 Table 5 indicates the amount received by each party, with a portion of the largess flowing to governors.

Except when they descend on Mexico City at year's end during the preparation of the national budget, state leaders thumbed their noses at PAN chief executives. Peña Nieto, who won the presidency in mid-2012, will seeks to rein in abuses. In addition, to bellying up to federal trough, the governors also:

- Enjoy sky-high salaries and fringe benefits;20

- Dominate state legislatures with princely salaries and extraordinary perks;21

- Control local electoral institutes that organize, monitor, and count the votes;

- Ensure that the local media served as megaphones for the state leaders by dolling out stipends to helpful reporters and directing that state agencies to advertise with friendly newspapers, magazines, and radio and TV stations;22

- Appoint members of transparency commissions that are supposed to promote decision-making in the sunshine, but, instead, have yanked down thick curtains to hide official actions. Not only is Mexico's freedom-of-information statute riddled with loopholes, but obtaining compliance from federal, state, and local governments is a nightmare for the hard-charging Federal Institute for Access to Information (IFAI);

- Allocate resources to the Integral Family Development program (DIF), generally headed by the governor's wife for a generous salary and created to look after adoption procedures, day-care centers, the well-being of abused spouses, and other vulnerable people;

- Forge economic ties to local businesses, enabling them to skirt the gauntlet of Byzantine regulations required to open, operate, and expand their enterprises;23

- Engage in blatant nepotism and award lucrative contracts to cronies and family members;24

- Play a major role in selecting candidates to succeed them, as well as nominees for the Chamber of Deputies, Senate, state legislatures, and mayorships;

- Run their own police forces;

- Influence the selection of local judges; and

- Administer non-federal prisons in their jurisdictions.

Conclusion

The debate over immigration reform has focused on its relevance for the United States and the illegal aliens who live within its borders. The discussion has failed to illuminate how the $21 billion in remittances helps corrupt, spendthrift governors and mayors divert public funds that could be used to address critical needs of their poorest citizens. Nor has attention zeroed in on the ubiquitous waste of resources on white elephants, unbid pharaonic projects beset by cost overruns and shoddy workmanship, outlays to friends and family members, and the sybaritic lifestyle, if not criminal actions, of elected officials. For example, the state government acted so slowly during the September 2013 deadly Hurricaine Ingrid that the notorious Gulf Cartel provided milk, juices, water, corn, and other foodstuffs to victims in Aldama and other municipalities in southern Tamaulipas state, which lies below Texas.25

End Notes

1 Justino Miranda, "'Helicóptero del amor' en desgracias; es embargado", El Universal, May 6, 2013.

2 Barnard R. Thompson, "Mexico Assassination Attack May Have Been Political Theater", Mexidata.info, March 22, 2004.

3 "Exhibe audio excesos y lujos de Andrés Granier", El Universal, May 15, 2013.

4 The secretary of government, known as Secretaría de Gobernación, is equivalent to the interior minister in many European countries with responsibility for the police, intelligence gathering, migration, and political affairs.

5 Quoted in "Gobernadores en México, los 'todopoderosos'", Radio Nederland \Wereldomroep, October 25, 2011.

6 "Siguen gobernadores mexicanos reforma migratorias en EUA: Ávila", El Periódico de México, July 22, 2013.

7 Alejandro Salmón Aguilera, "'Aberrante' blindaje fronteriza de EU: Duarte", El Diario, June 28, 2013.

8 Even though most governors have ties to narco-traffickers or close their eyes to their criminality, they continue to demand more funds to fight small-time dealers; see, "Gobernadores mexicanos demandarán 13,000 mdp para combatir 'narcomenudeo'", CNN México, July 11, 2011.

9 Quoted in Jorge Escalante, "Quiere el PRD auditoria Oliva por escultura", Reforma, April 7, 2008.

10 Juan Avizu, "Estela de Luz, emblem de una nueva era: FCH", El Universal, January 7, 2012; and "Por fin, la Estrela de Luz alumbra el Distrito Federal", Informador, January 8, 2012.

11 Claudia Guerrero and Maria Ibarra, "Piden rescatar a estados endeudados", Reforma, September 18, 2012.

12 Imelda García, "¿Qué entidades recibirán más recursos federales en 2013", ADN Político, January 2, 2013.

13 Claudia Salazar, "Dan más autos y más caros a diputados", Reforma, January 30, 2013; "Recibirán ¡2 coches! Monreal, Anaya", Reforma, February 2, 2013; "Se dan fistol de oro los 500 diputados", Reforma, December 6, 2012.

14 Claudia Salazar, "Dispara Cámara gaspos", Reforma, April 14, 1013; "Diputados mexicanos reciben pines de oro", Univisión, April 4, 2013; and the Sergeant at Arms Office of the U.S. House of Representatives supplied the $15 figure; telephone interview with author, August 21, 2013.

15 The chief justice earns $489,440; see, "Ministros de SCJN ganarán más que EPN y tendrán 'estimulo del Día de la Madre", Aristeguinoticias.com, December 11, 2012; Ricardo Gómez, "Dan mini iPad de regalo a diputados", El Universal, March 20, 2013; and President Enrique Peña Nieto earns 193,478 pesos ($15,478.24) each month.

16 Víctor Mayén, "13 PAN Yet to Return Funds", The News (Mexico City), July 25, 2013.

17 Erika Hernández, "Eleve gasto en servicios Presidencia", Reforma, March 31, 2013;

18 "Foto official de Enrique Peña Nieto costó más de $29 mil dólares", Univisión, March 8, 2013.

19 Instituto Federal Electoral (IFE).

20 Although state websites reveal far less information than in the past, examples of gubernatorial gross monthly salaries, excluding 15 percent year-end bonuses, multiple perks, and taxes, are Miguel Alonso Reyes of Zacatecas (110,484 pesos, or $8,838.72); Mario Anguiano Moreno of Colima (95,409 pesos, or $7,632.72 — a 30 percent increase between 2010 and 2013); Fernando Ortega of Campeche 168,309 pesos, or $13,464.72); César Jáquez of Chihuahua (118,109 pesos, or $9,448.72); Rolando Zapata of Yucatán (141,152 pesos, or $11,292.16); and Javier Duarte de Ochoa of Veracruz (74,313 pesos, or $5,945.04); see, "Gobernadores perciben altos sueldos en 2013", Informador.com.mx, January 3, 2013.

21 See George W. Grayson, "Mexican Officials Feather Their Nests While Decrying U.S. Immigration Policy", Center for Immigration Studies, April 2006.

22 Mexico's states spend 4,518,000,000 pesos or approximately $361.4 million in official publicity — a sum that doubled between 2005 and 2011. The 2011 figure is twice the outlay on the publication and distribution of school texts; see, "Gobernadores mexicanos gastan 4,518 mdp en publicidad oficial", El Financiero, April 10, 2013.

23 Governors, mayors, and other public officials receive generous Christmas presents often worth thousands of dollars; see, "Reciben gobernadores en regalos, los equivalente a gastos de tres mil familias", Ajuaa Noticias, December 20, 2012.

24 The PRD's Amalia García Medina, governor of Zacatecas (2004-2010) epitomizes the many practitioners of nepotism and cronyism. The former moderate communist placed her daughter, husband, sister, cousins, and sisters-in-law in key government posts, causing her ex-ally Raymundo Cárdenas to call her administration "the largest network of nepotism in the country". As part of her Amor por Zacatecas ("Love for Zacatecas") program, she awarded allies unbid contracts to construct a grand convention palace, for which the unexplained cost over-run was more than 358 million pesos ($28.6 million). Tenor Placido Domingo gave the opening performance; see, José Gil Olmos, "Zacatecas: Cisma Perredista", Proceso, April 10, 2010.

25 "Cartel del Golfo reparte toneladas de despensas por 'Ingrid' en Tamaulipas", Proceso, September 22, 1013.