Download a PDF of this Backgrounder

Dan Cadman is a fellow at the Center for Immigration Studies.

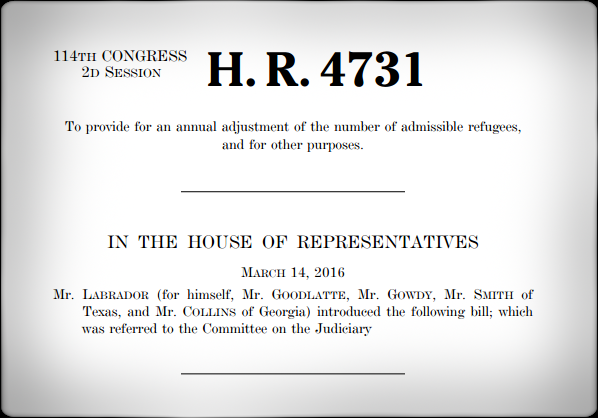

On March 14, Rep. Raul Labrador (R-Idaho) introduced a bill into the House Judiciary Committee on behalf of himself, Committee Chairman Bob Goodlatte (R-Va.), immigration subcommittee Chairman Trey Gowdy (R-S.C.), and others that would, if passed, substantially amend the U.S. refugee program. It is H.R. 4731, the "Refugee Program Integrity Restoration Act of 2016".

The bill contains some important amendments to the refugee program and merits favorable consideration. It was marked up by the committee on March 16 and passed to the full House for consideration, although unfortunately Govtrack.us only gives it an 11 percent chance of enactment.1

Here are the highlights:

Section 1. Establishes the short title of the bill (mentioned above).

Section 2. Changes the language of the provision of law that lays the foundation for the refugee program, Section 207 of the Immigration and Nationality Act (INA).2 Specifically, it amends subsections 207(a) and (b), which cumulatively has the effect of :

- Increasing the statutory number of permitted refugee admissions from 50,000 to 60,000, but conversely

- Removing presidential authority to adjust that figure upward, requiring him or her instead to recommend upward adjustments to Congress, which would retain final say on the recommendation.

Section 3. Tightens up the verbiage in INA § 207(c)(4), which permits termination of refugee status if it is determined that the alien is not entitled to that status, by:

- Substituting the phrase "shall be terminated" for "may be terminated" (emphases added), and

- Including new language requiring termination of refugee status if an individual returns to the country from which he claimed persecution when conditions in that country have not changed.

It also adds a new paragraph, 207(c)(5), requiring annual reports to Congress from DHS on the number of aliens whose refugee status is terminated under each of these new provisions.

Section 4. Adds a new paragraph, 207(c)(6), requiring the secretary to give priority consideration to individuals of minority religions claiming persecution on that basis from a country listed as "a Country of Particular Concern" in the annual report of the Commission on International Religious Freedom for the year preceding their applications.

Section 4 also specifically substitutes "Secretary of Homeland Security" for "Attorney General" everywhere the latter appears to ensure that the statutory language is updated to reflect reassignment of responsibilities consistent with the Homeland Security Act of 2002.

Section 5. Amends the language of subsection 207(c)(3) by limiting authority of the secretary to waive any grounds of inadmissibility other than those relating to health. This is a signal change because existing law permits the secretary to waive an abundance of grounds for exclusion, including various criminal offenses, frauds, etc. The sole exceptions to existing waiver authority being terrorism, national security, foreign policy, and genocide.

Section 6. Adds a new subsection, (g), to Section 207 that authorizes (but does not require) the secretary to conduct recurring security and background vetting checks on refugees up through the point at which they adjust status to become lawful resident aliens. The fact that such checks are not directed is mildly troubling; one doubts that, as presently constituted and under current leadership, DHS will ever of its own volition take such a step, despite the obvious need.

Section 7. Alters Section 209 of the INA, which deals with adjustment of status to lawful residence by refugees and asylees.3 The key modification is that it shifts the time frame in which a refugee may seek adjustment from one year after receipt of refugee status upward to three years. This is an important safety cushion for the American people insofar as it allows continued monitoring of incoming refugee flows and termination of status any time within the three-year period should the individual prove to be unfit.

One wonders whether the bill might have been strengthened had the authors taken the further step of requiring that, after three years, refugees then become conditional or temporary residents for an additional two years before being permitted to adjust to lawful permanent residence. A total of five years to become resident aliens does not seem unreasonable given the many troubled places, such as Syria, Somalia, Iraq, and Afghanistan, from which the United States presently receives refugee flows, places with dysfunctional or failed governments where the ability to vet applicants is doubtful at best.

Section 8. Mirrors Section 5 of the bill by limiting the authority of the secretary to waive grounds of inadmissibility, only in this instance by application to refugees seeking to adjust status to lawful permanent residence under INA Section 209. Like Section 5, it would preclude grants of waivers for any reason except health exclusions, thus eliminating the multiple waivers now available for individuals who have committed various offenses.

Section 8 also amends an anomaly of the refugee provisions by adding a new subsection, (d), to Section 209 of the INA by stating that the deportation grounds under Section 237 of the INA are also a basis for denial of adjustment of status, with the exception of the "public charge" deportation ground.4

This section of the bill additionally emphasizes through statutory language that the burden is on the alien to prove eligibility for adjustment by clear and convincing evidence, which must be presented at an in-person interview, and not simply by the filing of paperwork remotely through a government service center.

Finally, Section 8 provides that if an alien is denied adjustment of status (which, legally, is a form of admission to the United States), then five years after the date of the denial and recurrently every five years, he must "return or be returned" to the custody of DHS for inspection as to his admissibility as an immigrant. This seems to suggest that refugees who are denied adjustment must be physically taken into custody — presumably for removal proceedings. However, the "return or be returned" language is slightly confusing in that individuals granted refugee status have never been in DHS custody; they flow into the United States from abroad only after approval, often on government or nongovernmental organization charter flights.

Section 9. Amends INA Section 412,5 which provides for resettlement of refugees upon entry by adding a new subsection, (g), to make clear that refugees may not be resettled in any state where the governor or legislature has taken action to disapprove such resettlement, or in any local community where the mayor, chief executive, or legislative body of that community has similarly disapproved resettlement.

This proviso has been added in recognition of the significant impact resettlement can have on receiving communities — not only in the context of public safety and security, but also in terms of social and fiscal impacts incurred by the absorption: health and education costs; provision of housing, which may already be inadequate for the preexisting residents; availability of jobs; adequacy of police resources; etc. States and localities have lately objected strongly to being forced to accept incoming flows of refugees with no say-so in decisions by federal officials on where the relocations are to take place.

At present, INA Section 412 only requires that the federal agencies directing resettlement "consult" with state and local governments at least quarterly and "insure that a refugee is not initially placed or resettled in an area highly impacted ... by the presence of refugees or comparable populations unless the refugee has a spouse, parent, sibling, son, or daughter residing in that area". Courts have ruled that this does not permit state or local governments to impede federal resettlement plans, even over their strenuous objections.

Note that an amendment to this section of the bill offered by Rep. Ted Poe (R-Texas) was approved; it broadens the new limitations on resettlement of refugees by prohibiting resettlement of refugees in a state in any instance where:

- The federal resettlement director fails to provide the responsible state agency with a minimum of 21 days advance notice; or

- The governor certifies that the resettlement director has failed, in the sole opinion of the governor, to offer adequate assurances that the alien(s) to be resettled do not represent a security risk to the state.6

Note also that another amendment to this section was offered by Rep. Steve King (R-Iowa) and approved; it even further broadens the statutory limitations on resettlement of refugees in any state where such resettlement is disapproved — not only by the governor or legislature, but also by voter ballot "initiative, referendum, or other plebiscite activity".7

Section 10. Establishes the requirements for a benefits fraud assessment within 540 days (18 months) of enactment of the bill, focusing on the "most common ways in which fraud occurs" in refugee processing, along with on how to combat such fraud; it additionally requires a report to Congress on the outcomes of the study.

Section 11. Requires creation of a DHS document fraud detection program focused on use of bogus identity and travel documents by intended refugees. It encompasses:

- Placement of fraud detection officers at refugee screening locations with the authority to place a hold on refugee approvals until fraud or national security concerns are resolved; and

- Development of a searchable database for use by refugee and fraud detection officers that includes scanned and categorized examples of known documentary frauds.

Section 12. Requires that all refugee interviews be digitally recorded, although audio-only or both audio and video is not specified. The section also requires that at least 20 percent of the recorded interviews using interpreters be translated as a means of verifying the accuracy of the interpretations and that these reviews must take place before any applications are adjudicated in the overseas refugee camp or other location where the interviews are taking place. In the event that material mis-translations are discovered during the audit review, the interpreter is barred from further use, and all affected applicants must be re-interviewed before their cases will be adjudicated.

Note that the time frame for retention of the recordings has not been specified; this may be a weakness in the statutory language since, without such guidance, they may be destroyed or over-taped prematurely, resulting in loss of important evidence later should the individual prove to be a criminal, terrorist, or other national security threat.

Section 13. Tightens the statutory definition of "refugee" found at INA Section 101(a)(42) to preclude individuals who are fleeing generalized violence (as opposed to violence or persecution directed at them personally) from asserting that they are entitled to refuge, and similarly to ensure that, if the violence is directed at them as individuals, it is solely on the five legally identified grounds for seeking refuge: race, religion, nationality, political opinion, or membership in a particular social group.8

The amending language is an important first step — particularly in regard to distinguishing displacement by generalized violence from individual persecution. However, in recent years both administrative tribunals and U.S. courts have embarked on a path of judicial interpretation expanding "membership in a particular social group" to include, for instance, former gang members who are targeted by their prior criminal associates. One doubts that such indefensibly expansive interpretations fall within the ambit of legislative intent for that phrase. It is incumbent on Congress to roll back such interpretations to a position of logic and common sense. One wishes that this bill took on that task.

Section 14. Embeds in statute the requirement that vetting of intended refugees must include a review of Internet and social media sources to ensure that they are not national security threats.

Section 15. Requires the Government Accountability Office (GAO), within 18 months of enactment, to report on security of the revised program, including:

- U.S. government vetting procedures and partners;

- How decisions on approvals or denials are made; and

- How many refugees were approved and admitted, but later became involved in terrorism.

The GAO report must also include a section detailing all of the social benefits programs to which refugees are entitled, and the nature and extent of their use of them.

Conclusion

This is a solid bill with a number of features, which, if enacted, would substantially enhance safety and national security. It would also re-instill at least a modicum of public confidence in the refugee program, which has fallen into such disfavor as the result of poor decision-making and oversight as well as inadequate vetting.

One only wishes that the bill also addressed the thorny problem of relatives of refugees who "follow to join" the principal entrant. Such "follow-to-joins" are authorized under INA Section 207(c)(2)(A) and (B). They often consist of adult males, frequently of fighting age, who permit their spouses, children, or parents to become the anchors on which they obtain entry after those spouses, children, or parents are granted refugee status. This provision of law as administered is clearly a risk that merits deeper consideration, and perhaps legislative development of some kind of structured "time out" that better serves the public safety and national security.

On the issue in Section 3 of termination of refugee status if an individual returns to the country from which he claimed persecution, the bill should have included return not just the country of origin but also to the "country of first refuge", since, as the UN High Commissioner for Refugees guidelines note, "the foundation of resettlement policy is that it provides a durable solution for refugees unable to voluntarily return home or remain in their country of refuge." (Emphasis added.)

Similarly, one could wish that the bill had at the same time addressed the asylum program (found in Section 208 of the INA9), which suffers from the same inadequacies and material weaknesses as the refugee program and which is equally likely to adversely affect public safety by inappropriate grants to unworthy and/or dangerous individuals.

It is also worth noting that the GAO reporting requirements laid out in Section 15 of the bill do not require a statute to be accomplished, and would be worth having even now. One is confident that the authors of the bill need only send a letter of request to GAO, a legislative agency, to initiate the audit process.

End Notes

1 The text of H.R. 4731 can be found on the Govtrack.us website.

2 Section 207 of the INA is codified at 8 U.S.C. § 1157.

3 Section 209 of the INA is codified at 8 U.S.C. § 1159.

4 Section 237 of the INA is codified at 8 U.S.C. § 1227.

5 Section 412 of the INA is codified at 8 U.S.C. § 1522.

6 Amendment No. 1 to H.R. 4731, Offered by Mr. Poe of Texas.

7 Amendment No. 3 to H.R. 4731, Offered by Mr. King of Iowa.

8 Section 101(a)(42) of the INA is codified at 8 U.S.C. § 1101(a)(42) .

9 Section 208 of the INA, governing asylum procedures, is codified at 8 U.S.C. § 1158.