Summary

Some 2.7 million foreign-born job seekers will legally enter the U.S. labor market between 1991 and 1995 because of the recently legislated 35 percent increase in legal immigration, higher refugee admissions and easier work authorizations for certain illegal aliens.

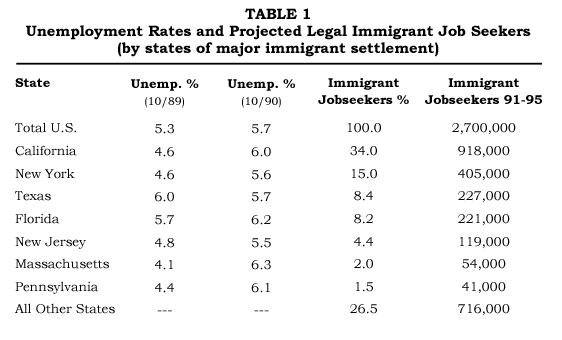

While this five-year increase will equal only 2.2 percent of the present national labor force, 70 percent of the new foreign born job seekers will concentrate in California and four other states. Four of the top seven immigrant receiving states now have unemployment at or above the national rate (5.7 percent in October 1990), with the national rate predicted to rise to between 6.5 and 8 percent in 1991. Some 750,000 illegal alien settlers will also enter the job market by 1995, more than half of them in California.

Nearly forty percent of all the newcomers and newly work-eligible will seek employment in Los Angeles, Miami, New York and Chicago, representing a ten percent increase in the labor force of those urban areas by 1995.

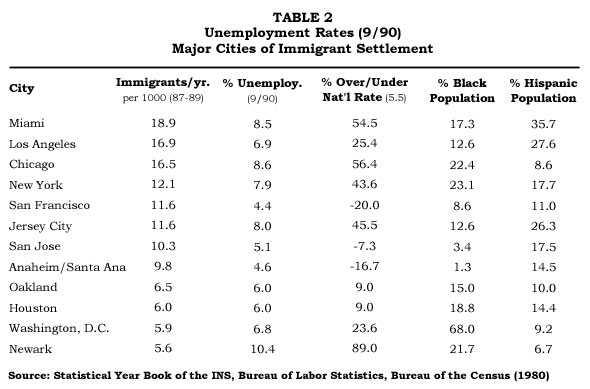

Nine of the top twelve cities of immigrant settlement — headed by New York, Los Angeles, Miami and Chicago — now have unemployment above the national average. African-American workers, whose unemployment rate is twice the national average, comprise more than 15 percent of the labor force in seven of the 12 cities. Hispanics, whose unemployment is 8.7 percent, represent more than ten percent of the labor force in nine of the cities.

34 urban areas of significant immigrant settlement are among the "labor surplus" areas designated by the Department of Labor in 1990 for federal procurement preferences, based on two or more years of unemployment 20 percent above the national rate.

Changes in the new law will increase the proportion of immigrants selected for skills only from about 4.2 percent to 7.2 percent of the total intake. About one third of the new legal entrants will continue to have less than an elementary school education. One half of them will continue entering semi-skilled and low skilled occupations where U.S. minorities are now concentrated.

Expanded Immigration: An Antidote to Feared Labor Shortages?

The "Immigration Act of 1990" enacted in November expands legal immigration by one-third from 530,000 to 700,000 yearly and gives legal access to the labor market to several hundred thousand Salvadoran illegal aliens and unlegalized dependents of amnestied aliens. The new law followed an executive branch decision October 12 to further expand refugee admissions in 1991 by another five percent, to 131,000 — more than doubling the annual low since 1987.

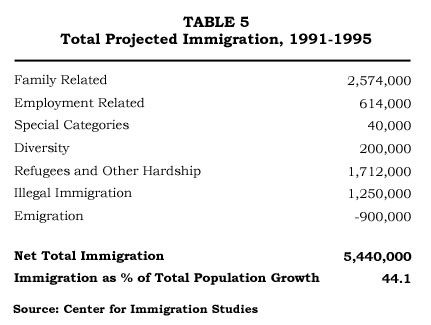

The expansion of legal immigration to 700,000 yearly, higher refugee numbers, continued admissions of parolees and asylees, and de facto legalization of Salvadorans and dependents of legalized aliens, is expected to boost overall legal intake to almost 1.1 million immigrants and other settlers beginning in 1991. Assuming a labor force participation rate of 67 percent, some 2.7 million additional foreign-born job-seekers will legally enter the U.S. labor market between 1991 and 1995, and about 750,000 illegally. (see Table 5).

This expansion of available legal workers was apparently intended by most legislators supporting the bill — originally known as the "Family Unity and Employment Opportunity Immigration Act" — who were influenced by a rush of books, articles and reports in the second half of the 1980s warning of impending labor shortages.

While those promoting the legislation emphasized the rewards of increased admissions of the highly skilled, the new law will not dramatically expand the actual inflow of skilled persons (excluding their dependents) — from about 25,000 a year now to some 60,000 after implementation. Continued heavy emphasis on family reunification, and special relief for Salvadorans and families of amnestied aliens, will ensure that about one-third of all legal immigrants will arrive with less than an elementary school education. One half will still gravitate to semi-skilled and low- skilled occupations of operators, fabricators and laborers, service workers, and farming and fishing. U.S. minorities are now overrepresented in these fields.

Increasing Workers, Shrinking Jobs: Immigration for "Job Creation"

Congress’s greater concern over possible future labor shortages rather than prospects of immediate unemployment helps explain why the 1990 reform, the fourth major reworking of legal immigration in this century, is the only one to be adopted on the downside of the business cycle. At the time of the new act's passage joblessness was rising and a recession imminent. Unemployment in October, 1990 stood at 5.7 percent — up from 5.3 a year earlier. The months of September and October saw actual shrinkage in the number of non-farm jobs.

Predictions of peak unemployment for 1991 from a number of economists and institutions now range from 6.5 percent to 8.0 percent.

A second cause for Congress's absence of concern for unemployment and job competition in the immigration debate was the wide acceptance of the proposition that immigration creates jobs. R The idea that immigration does not cause job displacement has been aggressively argued by many economists during the 19805, and supported by two authoritative U.S. agencies, the Council of Economic Advisors and the Department of labor. Even many of those economists acknowledging job displacement, tended to dismiss it as a short-term, transitory phenomenon whose ill-effects were far outweighed by immigration's long-term advantages.

Pro-natalist social scientists found receptive ears in the business community and pro-immigration advocacies in extending the arguments against job displacement to assert that that immigration can even be an antidote to slow growth and weak job creation.

"Immigrants don't take jobs, they create jobs" became a frequently invoked slogan in legislative debates beginning in 1987, usually with little or no scrutiny of the other complex variables bearing on that proposition.

The Wall Street Journal, a major advocate for immigration expansion, argued for the legislation as a "jobs bill." While the Attorney General warned Congress that excessive increases in numbers could draw a presidential veto, other convincing administration voices, such as the Chairman of the Council of Economic Advisors and the Commissioner of Immigration and Naturalization, either acclaimed the tonic effect of higher immigration or endorsed the proposition that immigrants create jobs.

The justification of immigration reform as a "jobs bill," however questionable, helped reassure skeptical legislators, giving them a political defense against constituents' fears of job displacement and allowing them to meet special interest demands for large increases in immigration in the face of consistent polls showing more than two-thirds of the general public opposed. Even African-American Congressmen heavily supported the expansionist legislation, raising few questions about the effects of added immigrant job competition on less-skilled black workers.

Likely Short-Term Pain for Uncertain Long-Term Gain

The long-term gains of larger immigration are at best only prospective, but the short-term pains of job competition and wage depression are now much closer at hand and likely to trouble less skilled and unskilled workers in a number of areas in the coming months as the labor market continues to soften.

Projected legal immigration over the next five years will increase the national labor force by about 2.2 percent. The effects of job competition, however, will be far more intense in some areas. As Table 1 shows, 70% of the new foreign born job seekers will concentrate in just five states. Four of the top seven immigrant settlement states, headed by California with more than a third of all newcomers, now have unemployment at or above the national average. Unemployment in two others, New York and New Jersey, show a clear rising trend.

Certain metropolitan labor markets will continue to receive a disproportionate share of the additional immigrant job seekers. Nearly forty percent of all the newcomers and newly work-eligible aliens will settle in Los Angeles, Miami, New York, and Chicago, increasing the total labor force in those metropolitan areas by nearly ten percent during the next five years.

Table 2 shows the country’s 12 most immigrant-impacted cities in terms of average annual immigration (1987-89) per 1,000 inhabitants. Recent settlement patterns are a reasonably good indicator of where immigrants are likely to settle during the next five years. Nine of the 12 cities show unemployment above the national average — markedly so for the top four cities of settlement: Miami, New York, Los Angeles, and Chicago.

Those four cities and several others of the remaining eight on the list are home to heavy concentrations of African-American and Hispanic minorities. Nationally, unemployment among blacks was 12.1 percent in September, more than twice the national rata and up from 11.7 a year earlier. Joblessness among Hispanics has risen from 8.3 percent to 8.7 percent in the year ending September 1990, fully 55 percent above the national rate.

Has Immigration Created Jobs?

If immigration creates jobs, little consistent evidence for that proposition is apparent in urban unemployment data. Unemployment is sharply up and job growth is down in New York or Los Angeles, Miami and Chicago while immigrant flows have remained high. Profuse immigration into Newark and Jersey City has not remedied those two areas' chronically weak job creation and lackadaisical economic performances.

Annually the Department of Labor determines which local jurisdictions are "labor surplus" areas qualified for special preferences in government contracting. Areas designated, which also qualify as "areas of substantial unemployment" for other U.S. government purposes, must have had unemployment 20 percent above the national average during 1988 and 1989. The cities listed on Table 4, which are taken from the Department of Labor's 1990 designations, also appear among the top fifty metropolitan receiving areas of immigrants between 1987 and 1989 in the Statistical Yearbook of the Immigration and Naturalization Service.

These data, like those in Table 2, offer little support for the theory of immigrant-stimulated job creation or the popular assumption that "immigrants go where the jobs are." What they do suggest is that significant immigrant settlement has occurred in areas of chronic labor surplus for a mixture of economic and non-economic motives, or is continuing to occur in areas where unemployment is rising rapidly. What the data portend is that an already loose labor market in many metropolitan areas is likely to become even looser with further expansion of immigrant admissions and work authorizations.

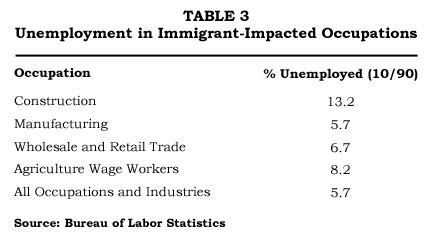

Similarly the data show that construction, manufacturing, wholesale and retail trade, and agriculture — occupations in which immigrants as well as U.S. minorities are overrepresented, are now experiencing unemployment at or above the national average.

Apparent from recent events is the continuing absence of coordination by the U.S. government between its employment and immigration policies. The 1990 expansion of immigration will pour more foreign-born job seekers. into labor surplus areas and trades just as other federal programs in many cases are striving to ease their unemployment through contracting preferences and other assistance. The full displacing effect of immigration, however, may not be fully reflected in the figures on joblessness. Withdrawal from the job market or out migration from the immigrant-impacted areas are frequently responses to heavy job competition.

Dr. Leon Bouvier, a demographer, is a former Vice President of Population Reference Bureau. currently Visiting Professor at the Tulane University School of Public Health, he is author of the forthcoming book, Peaceful Invasions: Immigration and Changing America to be published by the Center for Immigration Studies.