Download a PDF of this Backgrounder.

Don Barnett is a fellow at the Center for Immigration Studies and has published widely on refugee resettlement and asylum issues.

The State of Tennessee filed a lawsuit against the federal government in March 2017 claiming that the refugee resettlement program was an imposition by Washington over which the state had no control.1 The lawsuit is pending, but it highlights a deep problem with how the refugee resettlement program has evolved since the passage of the Refugee Act in 1980.

This Backgrounder traces the history of the federal-state relationship regarding refugees, identifies flaws, and proposes solutions. Among the findings:

- Repealing regulation 45 CFR 400.301 could have the immediate effect of allowing states to withdraw from the U.S. Refugee Admissions Program (USRAP) and end initial resettlement activities in the state.2

- Today, states that withdraw from the program find the program continues in the state with the potential to operate on a larger scale than before withdrawal and with no state participation.

- As implemented, states have a limited and ill-defined role in the federal USRAP.

- Congress has shirked its responsibility to fully fund the refugee resettlement program.

- The federal government has shifted much of the fiscal burden of refugee resettlement to states. Three years of reimbursement for the state portion of welfare programs used by refugees in the state, such as Medicaid, TANF and SSI, was authorized by the 1980 Refugee Act. This support was ended entirely.

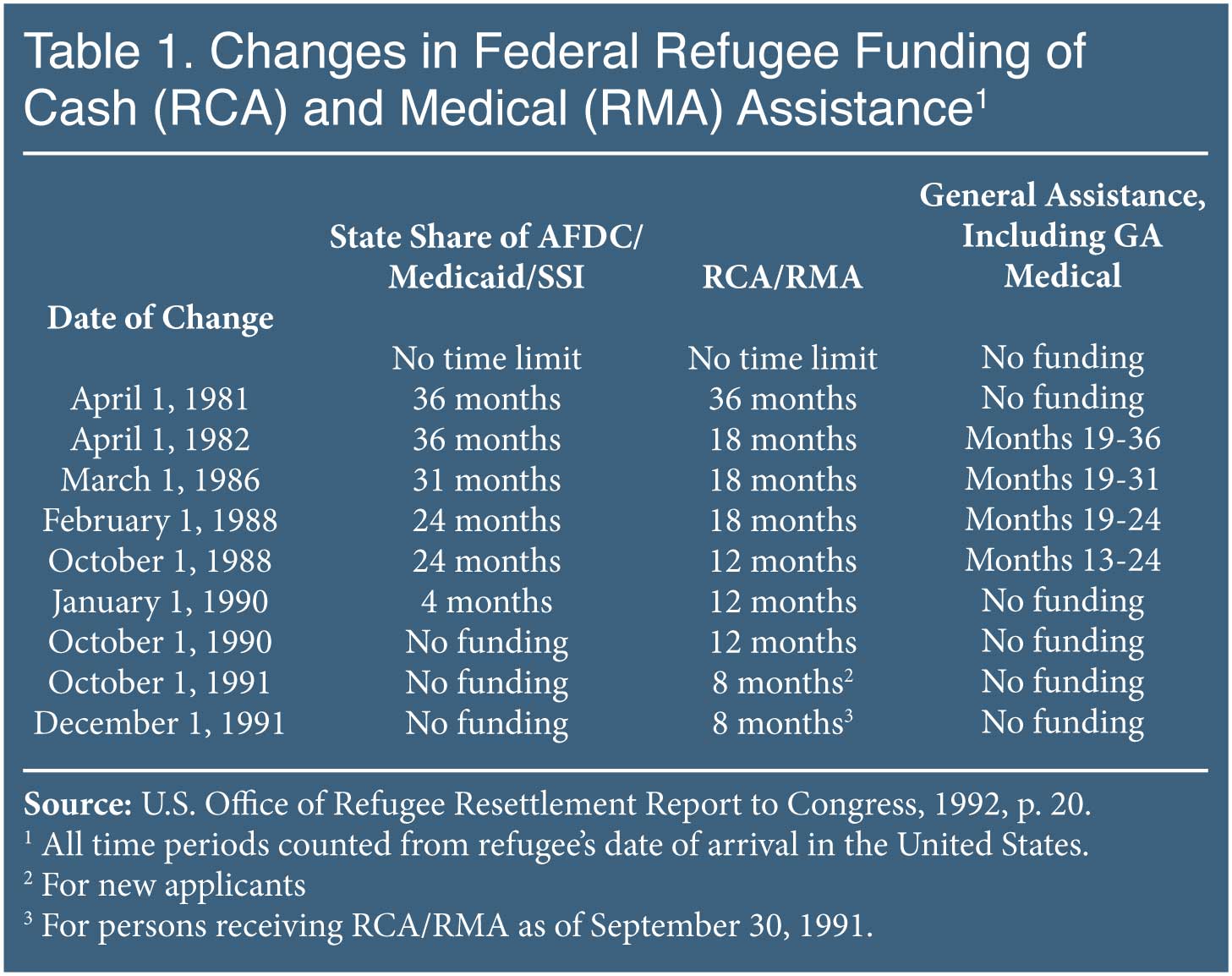

- The Act authorized Refugee Medical Assistance (RMA) and Refugee Cash Assistance (RCA) for three years for refugees who do not qualify for cash welfare and Medicaid. This support was gradually scaled back; today RCA and RMA are available for only eight months.

- This cost shift to the states means the federal government is, in effect, using state funds to operate a federal program. In cases where a state asks to withdraw from the program, continuation of the program means the state has lost its ability to control its own budget and is deprived of its sovereignty under the Tenth Amendment.

- Consultation among "stakeholders" about where refugees are to be settled is ill-defined in the USRAP. At times there is no meaningful consultation with state authorities.

- The federal government uses a legally questionable regulation (45 CFR 400.301) rather than statutory law to allow private non-profits to operate in a state where the state has asked to withdraw from the program.

- By one reading of the law, prior to 45 CFR 400.301, there was no authority to resettle refugees in states that chose to withdraw from the program. In other words, prior to 1994 when 45 CFR 400.301 was introduced, the states were — knowingly or not — participating in and paying for a voluntary program from which they had every right to withdraw at any time with the expectation that no refugees would be resettled in the state.

Introduction

According to the House Judiciary Committee press release introducing the "Refugee Program Integrity Restoration Act" (H.R. 2826), the bill "prevents the resettlement of refugees in any state or locality that takes legislative or executive action disapproving resettlement within their jurisdiction."3 The press release notes that, "Currently, states or localities that do not want refugees resettled within their communities have no recourse."

In contrast to this concern over the lack of a state voice in refugee resettlement, official State Department policy affirms that "PRM [Department of State's Bureau of Population, Refugees, and Migration] carefully considers all input received when approving placement plans in each proposed location, and accommodates the input received from the states to the extent feasible. In the overwhelming number of cases, PRM grants states' requests to reduce or hold steady the number of refugees to be resettled in a given community," according to a department spokesperson. Also, "Both reductions and increases as a result of state input to the U.S. Refugee Admissions Program process happen regularly as a part of our ongoing consultative process," according to the spokesperson.4

So, which is it?

A brief history of the federal refugee program vis a vis states' rights and obligations will show that concern about the impact of the program upon states was paramount from the inception of the 1980 Refugee Act. Subsequent legislation, regulation, and congressional appropriations nullified initial promises of support and cut off any means the states may have once had of escaping the fiscal burden that the federal government has shifted to them.

The Refugee Act of 1980

In his paper recounting the conference committee process involving the Refugee Act, Senate sponsor Edward Kennedy noted:

Because the admission of refugees is a federal decision and lies outside normal immigration procedures, the federal government has a clear responsibility to assist communities in resettling refugees and helping them to become self-supporting. The basic issues here were the length of time of federal responsibility and the method of its administration. State and local agencies were insistent that federal assistance must continue long enough to assure that local citizens will not be taxed for programs they did not initiate and for which they were not responsible.5

Further, he wrote that the program would "assure full and adequate federal support for refugee resettlement programs by authorizing permanent funding for state, local and volunteer agency projects." (Emphasis added.)

The Refugee Act intended to insulate states from refugee costs. Unlike other legal immigrants, refugees are eligible for all federal welfare programs on the same basis as citizens upon arrival. (This is a lifetime entitlement for refugees who become citizens.) The Act authorized three years of federal medical support and cash support for those refugees who do not qualify for cash welfare or Medicaid. Additionally, the Act authorized federal reimbursement to the states for three years of the state's portion of Medicaid, TANF, SSI, etc. paid on behalf of each refugee resettled in the state. The ongoing cost for support of refugees on public assistance is, by far, the biggest portion of the overall cost of the program and is not accounted for in any official cost estimates.

The Act's three years of federal support was understood to be inadequate. The 1981 Select Commission on Immigration and Refugee Policy seemed to well understand the fiscal issue for a federal program that passed its costs to state and local governments, finding that "Areas with high concentrations of refugees are adversely affected by increased pressures on schools, hospitals and other community services. Although the federal government provides 100 percent reimbursement for cash and medical assistance for three years, it does not provide sufficient aid to minimize the impact of refugees on community services."6

Even this admittedly inadequate federal support was to be drastically cut over the years.

The three-year time frame for federal reimbursement to states for the state contribution to federal welfare programs used by refugees was gradually shortened and halted completely by 1991, resulting in a significant cost shift to the states. For example, today about half of all refugees arriving in the last five years are in Medicaid. About a third of those who have been in the country for five years are in Medicaid — about twice the national average.7 Medicaid is jointly funded by the federal government and states, with the state share, on average, about 37 percent of total program costs. Denial of the authorized three years of Medicaid support means a cost shift to states that runs into the billions annually for Medicaid alone.8 (Public education, Medicaid, and ELL are likely the largest individual program costs that have fallen to states from refugee resettlement. Other state-funded welfare programs available, depending upon the state, include state general assistance, a state cost component for TANF and SSI, and other smaller state poverty programs.)

At the same time that federal support to the states for those refugees on welfare was trailing off, direct federal support to refugees who are not eligible for welfare was gradually reduced from the authorized three years. By 1991, this support, known as RMA (Refugee Medical Assistance) and RCA (Refugee Cash Assistance), was reduced to eight months — another significant cost shift to states and local communities.

A 1990 GAO report reviewing the history of the program found that, "With reductions in federal refugee assistance, costs for cash and medical assistance have shifted to state and local governments."9

Congress has not funded this program to anywhere near needed levels. It clearly has imposed costs on states that it acknowledged are the responsibility of the federal government. A 2010 Senate report concluded that "the practice of passing the costs of resettling refugees on to local communities should not continue."10

Welfare Dependence and "Self-Sufficiency"

Refugee program law and regulations require refugee "self-sufficiency" and early employment with annual reporting on achievement in this area.

The program's staggering dependence on public welfare programs has not gone unnoticed and brought several responses at the federal and state level.

The Office of Refugee Resettlement (ORR) seemingly offered its own response to the issue by merely changing the definition of "self-sufficiency". In ORR's novel definition, a refugee can be in public housing, receiving Medicaid, food stamps, cash from SSI, etc. and still be considered "self-sufficient" by the government. Only TANF or Refugee Cash Assistance causes a refugee to lose the "self-sufficient" designation.11 Needless to say, refugees achieve "self-sufficiency" in a surprisingly short period of time.

Concerned that a "disproportionate number of refugees end up on welfare rolls" and wanting "alternative approaches to this welfare dependency cycle" — in the words of then California Senator and immigration conservative Pete Wilson — the so-called Wilson-Fish amendment was introduced in 1984.12 This model provides a program of extra social services money in the early stages of resettlement to those agencies that resettle refugees who temporarily stay off of welfare rolls. There is no evidence that the amendment, which encourages "self-sufficiency, reduces welfare dependency, and fosters greater coordination among the resettlement agencies and service providers", achieved any of its aims, but it was another win for the private refugee contractor industry as it meant more federal dollars to the contractors, with fewer strings attached, earlier in the process.

The Wilson-Fish program was intended by Congress to be "revenue neutral" over the long run when compared to the standard operating model, but that requirement was removed by ORR in 1992.13 Not only would the contractors (referred to variously in government documents as "voluntary agencies", "volags", "resettlement agencies", and "private non-profit organizations") be getting their money front-loaded, they would now be getting more of it.

Today there are 13 states operating under the Wilson-Fish program and at least three others transitioning over to the program.

Match Grant, another program aimed at early employment for refugees, as well as an attempt to induce the contractors to participate with their own resources, today promises contractors $2,200 for each refugee who temporarily stays off cash welfare. As originally implemented in the early 1980s, contractors were to provide one dollar for each "matching" federal dollar. Today, contractors provide 10 cents plus 40 cents of "in-kind" donated furniture, cars, unpaid volunteer time, etc., for each dollar received from the federal government.

As more and more costs were transferred to the states, the contractors picked up the cause of "privatization".

The argument behind "privatization" is that, left to their own devices, the contractors would come up with better ways to spend government money helping refugees integrate into the economy. (The federal government provides the bulk of support for the refugee program, with state governments in second place.) Of course this is not "privatization" in the common-sense definition of that term. A private program would consist of private sponsors who cover the costs of refugee resettlement, which was more or less the case prior to the 1980 Act. Since 1980, the basic operating model of more refugees resettled equals more government money has brought predictable incentives and results.

The "alternative approaches" and social programs are funded out of federal grants and there are no consequences if they fail to produce the desired results. The hedge around welfare usage under the Wilson-Fish umbrella or Match Grant is practically meaningless. Programs that most Americans think of as "welfare", such as food stamps, Medicaid, and housing assistance, are still available upon arrival to refugees under these alternative programs. ORR is so concerned to maintain refugee eligibility for these programs that its FY2017 Match Grant written guidelines advise resettlement agencies to use vouchers if necessary to avoid having weekly cash payments make refugee clients income-ineligible for food stamps and Medicaid.14Most importantly, restrictions on accessing the entire panoply of welfare assistance are lifted after the alternative programs have run their course — six months for Match Grant and eight months for Wilson-Fish-specific "alternative approaches to this welfare dependency cycle".15

A comprehensive "privatization" plan was put forth in 1992 by then ORR Director Chris Gersten. This plan would have run the entire resettlement program like a Wilson-Fish program. According to 1996 testimony from Gersten (by then no longer ORR Director), ORR had secured congressional approval for the plan, known as the "Private Resettlement Program" (PRP), however, "the state refugee coordinators sued HHS in the 9th Federal Circuit Court and had the plan halted on the technicality that HHS had violated the Administrative Procedures Act."16

State Concerns About Cost

There has been steady, though unreported, objection from states about their costs from the program. The National Governors Association periodically issues complaints about the obligations placed upon states without consultation by the program.17 Objections are muted now with the national annual refugee quota at 45,000. When the Obama administration raised the 2017 quota to 110,000 — subsequently lowered by Trump in January 2017 — many states requested relief from the program. In all, 30 states asked to be excluded from the resettlement of Syrian refugees and four states asked to be excluded from the program altogether as a result of the plans to resettle refugees from the Syrian civil war and the sharp overall refugee quota increase.18

The Senate report from the 1992 Reauthorization of the Refugee Resettlement Act acknowledged that the decision to stop reimbursing states for the state cost of Medicaid and cash welfare was causing pain at the state level:

[S]ome smaller states indicate that they may eliminate their refugee programs entirely with such a cut [reimbursement to states]. And a consequence of such funding cuts is pressure to reduce the number of refugees admitted for resettlement at a time when commitments continue to Vietnamese political prisoners, Amerasian children, Soviet Jews, and others. The prospect of these cuts has jeopardized the current refugee program.19

Likely in response to rumblings from state governments about getting out of the program, the Clinton administration promulgated regulations in 1994 (45 CFR 400.301) that allowed a resettlement contractor to continue operations in a state that had withdrawn from the program. This arrangement allowed private contractors to operate independently without any input from state governments. By regulatory fiat rather than by statute, it guaranteed that a state could never get out of the program or escape the fiscal impact on state revenues.

Maine, Texas, New Jersey, and Kansas asked to withdraw from the resettlement program after the Obama administration raised the annual refugee quota to 110,000. Alabama, Alaska, Kentucky, Louisiana, Nevada, and Tennessee state governments withdrew from the program earlier.

In Maine Governor LePage's letter withdrawing from the program, the governor wrote that he had "lost confidence in the federal government's ability to safely and responsibly run the refugee program," citing a Syrian refugee from Freeport, Me., who died fighting with ISIS. "This is not the only example of a terrorist-linked refugee having lived in Maine," he continued.20

Speaking of the costs to Maine's taxpayers, he wrote, "Maine's social services, schools, infrastructure and other resources are being burdened by this unchecked influx of refugees. ... We have also found that welfare fraud is especially prevalent within the refugee community."

None of these states saw a reduction in refugee numbers as a result of their withdrawal from the program. Their numbers did go down, but that was because the national quota was cut in half. According to ORR, while a state has the right to get out of the program, "If a State chooses to withdraw from the Program, then under the 1984 'Wilson/Fish Amendment' (so-named after the legislation's sponsors), ORR may select one or more other grantees, typically private non-profit organizations, to administer federal funding for cash and medical assistance and social services provided to eligible refugee populations in that State."21

Actually, it is the 1994 regulation (45 CFR 400.301), not the statutory 1984 Wilson/Fish Amendment that allows for the federal government to bring in a private contractor to run the program when the state has exited the program. The Wilson/Fish statutory amendment does not grant authority to either HHS or ORR to fund an alternative program as a way to establish or continue an initial resettlement program in a state when that state has withdrawn from the federal program. It unintentionally provided a framework and funding that is more advantageous to the contractors. That is why it is the preferred mode of contractor operations when a state has withdrawn from the program.

Ironically, what was meant to reduce costs and ensure accountability became a boon to the contractors, which together with regulation 45 CFR 400.301, allowed them to bypass any state influence and impose even more costs on the states where they operate. (Some states that got out of the program saw the number of refugees brought to their state go up dramatically after the contractor came in as the sole administrator of the program. A state refugee coordinator told me his state would never ask to exit the program as that would mean loss of what little influence he was able to exercise over the placement of refugees in his state.)

Thus evolved what was seen at the time to be a laudable baby step toward making the program more accountable. As with many such half-measures to "privatize", it was instrumentalized to the advantage of the very entities it was meant to control. The adage holds: Public money always drives out private money.

There is no mention anywhere in the 1980 Refugee Act or elsewhere in immigration law about what should happen when a state withdraws from the program. Refugee law, to the extent it mentions state prerogative, theoretically allows a state refugee coordinator to refuse resettlement.

What Consultation?

According to the left-leaning Washington think tank Migration Policy Institute (MPI), publicly funded private resettlement agencies:

[M]eet with state and local agencies on a quarterly basis regarding the opportunities and services available to refugees in local communities and the ability of these communities to accommodate new arrivals. They also consult with the state refugee coordinator on placement plans for each local site. ... [i]f a state opposes the plan, PRM [State Department] will not approve it. [Emphasis added.]22

MPI finds in its EU-funded report that, "According to refugee volunteer agencies, states occasionally oppose placement plans that local resettlement agencies had previously presented to them."23

No state has ever been allowed to exit the program completely, though that was clearly the intent of the state of Maine, for example. It is less clear that the other states that asked to leave the program thought in terms of stopping all initial resettlement to their state, but they certainly did not expect their state refugee quota to go up — and that will be the result if the national refugee quota goes back up to historical levels.

As for the effectiveness of the "ongoing consultative process" in respecting a state's demands, interviews with state refugee coordinators reveal that the federal government has completely ignored state requests for a reduction of numbers in some cases. In most cases, state refugee coordinators seemed willing to accept the refugee quota assigned to their state without objection. The state quota is arrived at by the private contractor and the U.S. State Department, sometimes with input from the state refugee coordinator.

Richard Thompson, president and chief counsel of the Thomas More Law Center, says the consultation requirement is a "vague requirement that has little impact on the federal refugee resettlement program. All it requires is some sort of communication between federal and state authorities; the federal government can implement its settlement program regardless of how vehemently the state objects."24

The official consultation process around state quotas remains opaque in the best of cases. We don't know what goes on in the way of unofficial backroom deals that may affect which refugees get settled where. Did Wyoming and Delaware, states that got zero and a few dozen refugees, respectively, over the last 37 years, get a break for legislative deals with then-Sens. Alan Simpson and Joe Biden? Are "red" states being intentionally targeted for refugee resettlement?

A 2012 GAO report titled "Refugee Resettlement: Greater Consultation with Community Stakeholders Could Strengthen Program" highlights the murky process of deciding how many refugees to place in a community:

Although the Immigration and Nationality Act states that it is the intent of Congress for voluntary agencies to work closely with state and local stakeholders when making these decisions, the Department of State's Bureau of Population, Refugees, and Migration (PRM) offers limited guidance on how this should occur. Some communities GAO visited had developed formal processes for obtaining stakeholder input after receiving an overwhelming number of refugees, but most had not, which made it difficult for health care providers and school systems to prepare for and properly serve refugees. ... most public entities such as public schools and health departments generally said that voluntary agencies notified them of the number of refugees expected to arrive in the coming year, but did not consult them regarding the number of refugees they could serve before proposals were submitted to PRM. [Emphasis added.]25

In those states where the program is wholly run by the contractors, usually as a Wilson-Fish site, consultation is even more hidden from the public.

According to the State Department:

PRM requires local resettlement agencies to consult quarterly with state and local government officials for the purpose of planning for refugee arrivals and discussing any issues that could impact the local community's capacity to adequately receive refugees. Local consultation includes representation from the state refugee coordinator, state refugee health coordinator, local governance, and local offices of health, welfare, social services, public safety, and public education. [Emphasis added.]26

But when a state officially withdraws from the refugee resettlement program, there is no longer a refugee coordinator or refugee health coordinator employed by the state. In such a state — usually re-configured as a "Wilson-Fish" site — the contractor assumes the function of refugee coordinator and state refugee health coordinator. That is, the state refugee coordinator with a theoretical right to affect the numbers brought to the state is now an employee of the private agency operating resettlement activities in the state. To the extent there is any "consultation" before recommending resettlement numbers in a Wilson-Fish state, it is largely among parties that belong to the same organization — the organization with the most to gain from expansion. Further, once state employees are out of the process, state open records law cannot be brought to bear on refugee resettlement within the state.

By one reading of the law, prior to 45 CFR 400.301, there was no authority to resettle refugees in states that chose to withdraw from the program. In other words, prior to 1994 when 45 CFR 400.301 was introduced, the states were — knowingly or not — participating in and paying for a voluntary program from which they had every right to withdraw at any time with the expectation that no refugees would be resettled in the state. Regulatory fiat has supplemented if not supplanted law in this area. Solely on the basis of this regulation a state getting out of the program will find that refugees are still being placed in the state at state expense. The same contractors will run the program and in most ways resettlement will look just like it did before the state withdrew from the program except that the state will no longer be even a minor participant in the program it is paying for.

Currently, states that opt out find themselves with no control over the program and likely with a larger program than before withdrawal.

Tennessee Decides to Sue

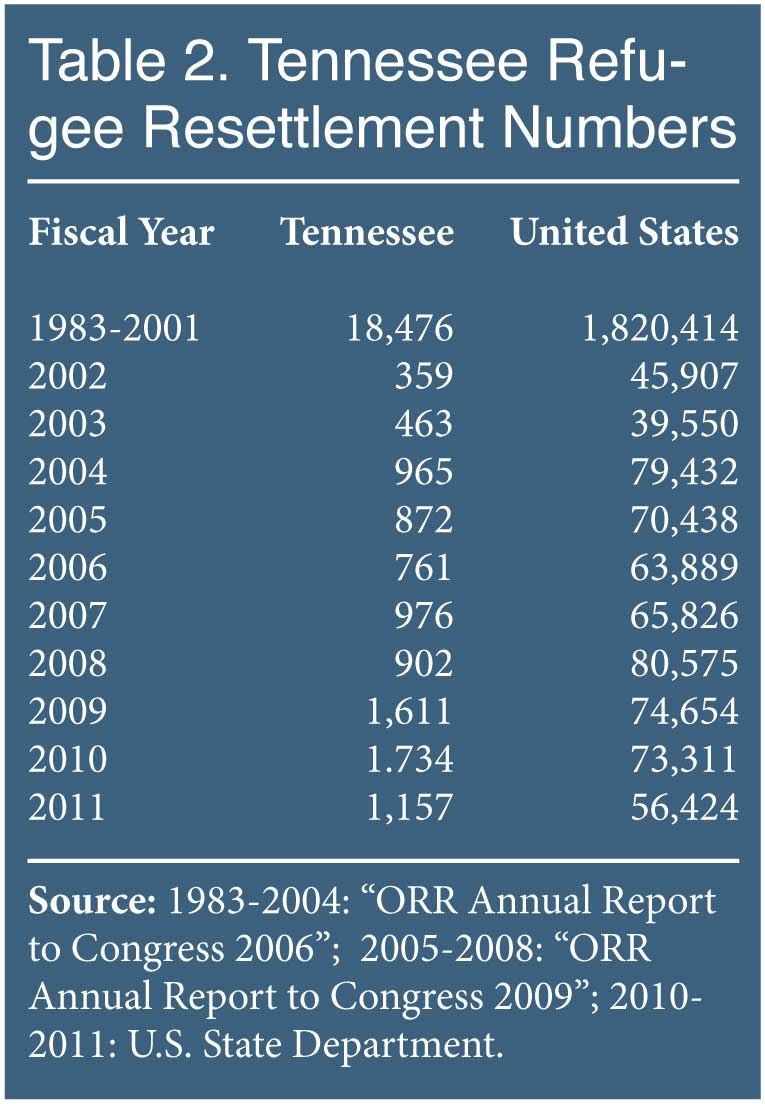

Tennessee, which opted out in 2008, found that its resettlement numbers increased by more than 75 percent immediately after it withdrew from the program, and stayed higher even while the national quota was declining. (See Table 2.) The contractor, Catholic Charities of Tennessee, was not even willing to share data about how many refugees it placed in welfare or share information about the status of refugee health, information that previously would have been tracked through its state refugee and health coordinators.

In response, the Tennessee legislature proposed to sue the federal government to halt the placement of refugees in Tennessee.

The legislative initiative to launch the lawsuit was opposed by Democrats and the Chamber of Commerce. The state attorney general opposed the measure and establishment Republican Governor Bill Haslam probably would have vetoed any legislation that called for a lawsuit, but the initiative was framed as a joint resolution and thus did not need the governor's signature.

Some of the Republican leadership worked to block passage of the legislature's resolution. The last obstacle in the Tennessee General Assembly's path — a requirement that the initiative have zero fiscal impact on the budget — was overcome when the Thomas More Law Center, a public interest law firm, took the case on a pro bono basis at no charge to the state or General Assembly and filed the suit in March 2017 (State of Tennessee v. United States Department of State, et al.).

Asserting that the state must have final say over state taxpayer dollars, the suit argues that the federal government is commandeering state resources to implement a federal program.

"The Constitution does not confer upon the federal government the unbridled power to direct state spending or interfere with a state's control over its own budget," according to Richard Thompson of the Thomas More Law Center. Further, "the federal government commandeered state funds to operate a federal program. Tennessee lost its ability to control its own budget and was deprived of its sovereignty under the Tenth Amendment."27

In the same that way DHHS had threatened those states that refused Medicaid expansion under the Affordable Care Act (ACA), DHHS would likely have threatened to withhold all Medicaid funding for state residents in Medicaid if Tennessee, as a result of refusing resettlement in the state, failed to pay its share of the Medicaid bill for refugees in the state.

Forced Medicaid expansion was challenged in NFIB vs. Sibelius, 567 U.S. 519 (2012). The Supreme Court agreed that forcing states to acquiesce to expansion of joint federal-State Medicaid as called for by the ACA violated the Spending Clause and the Tenth Amendment. At the time, the Court noted that "The States are separate and independent sovereigns. Sometimes they have to act like it."

In Printz v. U.S., 521 U.S. 898 (1997), a precedent referenced in the Tennessee suit, the Supreme Court found the federal government had overstepped its bounds by requiring a locality to pay for the background checks required of the federal Brady Handgun Violence Prevention Act, resulting in commandeering of state resources.

The ACLU has sought to be named a defendant in the Tennessee case and the Department of Justice moved to dismiss the case. So far no decision has come down on the ACLU petition or on the government's motion to dismiss the case.

According to the Thomas More Law Center, the wait of now 10 months without hearing from the Court is not unusual.

A ruling in the state's favor would negate regulation 45 CFR 400.301 and make the theoretical right to withdraw from the program no longer theoretical.

At the federal level, simply rescinding regulation 45 CFR 400.301 would do much to re-establish state prerogative in this program, correct the inherent 10th amendment problem in the regulation's implementation, and restore the federal program to an opt-in status as intended.

Repealing this regulation is the quickest and easiest route to restoring a state's right to withdraw fully from the U.S. refugee resettlement program and halt the initial resettlement of refugees within its borders. It would not necessarily obviate the need for Tennessee's lawsuit. That lawsuit addresses the larger question of to what extent the federal government can compel a state to pay for a federal program that the state does not want implemented within its borders and/or elects not to fund with state resources in deference to other state funding priorities.

Passage of the Refugee Program Integrity Restoration Act, which seems unlikely in any event — especially in the Senate — would also not necessarily obviate the need for Tennessee's lawsuit. The Refugee Program Integrity Restoration Act does not address the operative regulation 45 CFR 400.301 and it is possible that states operating under this regulation would not get any relief as they could be considered outside the ambit of the federal program.

Ultimately the courts will have to define the state's place in this program and answer the question "Do states have an authentic and meaningful say in the refugee resettlement program?"

End Notes

1 State of Tennessee v. U.S. Department of State.

3 "Labrador & Goodlatte Introduce Bill to Reform the Refugee Program", House Judiciary Committee press release, June 8, 2017.

4 Email to author from State Department spokesperson, November 22, 2017.

5 Edward M. Kennedy, "Refugee Act of 1980", International Migration Review, v. 15, no. 1-2, Spring-Summer 1981.

6 "U.S. Immigration Policy And the National Interest: The Final Report and Recommendations of the Select Commission on Immigration and Refugee Policy with Supplemental Views by Commissioners", Select Commission on Immigration and Refugee Policy, March 1, 1981. See also, Kenneth D. Basch, "Federal Responsibilities for Resettling Refugees", Urban Law Annual; Journal of Urban and Contemporary Law, v. 24, January 1983, pp. 157-158 ("[L]ocal communities have had to increase public services, often at their own expense.").

7 "Office of Refugee Resettlement Annual Report to Congress 2015", Office of Refugee Resettlement , January 23, 2017. See Table 7, "ASR Respondents' Public Benefits Utilization by Arrival Cohort, 2015 Survey".

8 The July 29, 2017, draft of the DHHS report "The Fiscal Costs of the U.S. Refugee Admissions Program at the Federal, State, and Local Levels, from 2005-2014" found that the entire population of refugees in the United States, some 2.9 million, used $47.5 billion in Medicaid in the 10 years that the study covered. Refugees and families (includes American-born children) used $65.3 billion of Medicaid in the same period. About 37 percent of this total is covered by state governments according to the Kaiser Family Foundation.

9 "Refugee Resettlement: Federal Support to the States Has Declined", U.S. General Accounting Office, December 1990.

10 U.S. Senate Committee on Foreign Relations, Abandoned Upon Arrival: Implications for Refugees and Local Communities Burdened by a U.S. Resettlement System that is Not Working, Washington, D.C.: Government Printing Office, 2010.

11 "Refugee Resettlement: Greater Consultation with Community Stakeholders Could Strengthen Program", GAO-12-729, U.S. Government Accountability Office, July 25, 2012. See p. 27: "ORR considers refugees self-sufficient if they earn enough income that enables the family to support itself without cash assistance — even if they receive other types of noncash public assistance, such as Supplemental Nutrition Assistance Program benefits or Medicaid." Cash assistance includes both refugee cash assistance and payments received under the Temporary Assistance for Needy families (TANF) program.

12 130 Congressional Record 28,364, October 2, 1984.

13 1992 ORR funding announcement.

14 ,a href="https://www.acf.hhs.gov/sites/default/files/orr/fy_2014_matching_grant_…" target="_blank">"FY 2014 ORR Voluntary Agencies Matching Grant Program FY 2014 Program Guidelines", Office of Refugee Resettlement, 2014, see p. 9.

15 Email to author from ORR spokesperson, January 12, 2018.

16 "Possible Shifting of Refugee Resettlement to Private Organizations", hearing before the House Committee on the Judiciary, Subcommittee on Immigration and Claims, August 1, 1996.

17 National Governors Association website. The complaints come and go, perhaps depending on NGA leadership. From NGA website 2009:

States have continually urged the federal government to establish a mechanism to ensure appropriate coordination and consultation. However, significant progress has not been made and the following mechanisms need to be considered to address this problem.

- There should be a requirement in the State Department/VOLAG contract to limit placement to areas conducive to resettlement. In addition, VOLAGs and their local affiliates should be required to have a letter of agreement that specifies that there has been consultation and planning for the initial placement of refugees and sets forth the continuing process of consultation. The requirement in the State Department/VOLAG contract to target placement to areas conducive to resettlement should include concurrence by the state.

- DHS, the U.S. Department of State (DOS), and the Office of Refugee Resettlement should coordinate with states receiving entrants and refugees. Entrants should be made eligible for DOS assistance for thirty days, or another mechanism should be developed to allow for a smooth transition of entrants into a community. The current system, in which an entrant simply arrives in the United States without any knowledge of the state, creates a tremendous burden on the community, leaves gaps in the provision of services, and provides no foundation for planning purposes.

- Governors should be closely involved in the congressional consultation process through which new refugee admissions levels are determined to ensure that program funding is provided to support the level of refugee admissions.

18 See Arnie Seipel, "30 Governors Call For Halt To U.S. Resettlement Of Syrian Refugees", NPR, November 17, 2015. According to an email to the author from ORR spokesperson on September 6, 2017, Maine, Texas, New Jersey, and Kansas officially withdrew from program after the national quota was raised to 110,000.

19 "Refugee Resettlement Reauthorization Act of 1992 : Report (to accompany S. 1941)", U.S. Senate. Committee on the Judiciary.

20 Letter from Maine Governor Paul R. LePage to President Obama withdrawing from Refugee Resettlement Program, November 4, 2016.

21 Memorandum of Facts and Law in Support of Defendants' motion to dismiss, June 1, 2017.

22 Donald M. Kerwin, "The Faltering U.S. Refugee Protection System: Legal and Policy Responses to Refugees, Asylum Seekers and Others in Need of Protection", Migration Policy Institute, May 2011, p.10. Fort Wayne, Ind., and Clarkson, Ga., city officials interviewed for the U.S. Senate Committee on Foreign Relations report "Abandoned Upon Arrival", stated that they had never been consulted or given notice by resettlement agencies or PRM about upcoming resettlement.

23 Ibid.

24 Email to author from Richard Thompson, December 13, 2017.

25 "Refugee Resettlement: Greater Consultation with Community Stakeholders Could Strengthen Program", GAO-12-729, U.S. Government Accountability Office, 2012.

26 Email to author from State Department spokesperson, November 22, 2017.

27 Email to author from Richard Thompson, December 13, 2017.