Download a PDF of this Backgrounder

Dan Cadman is a fellow at the Center for Immigration Studies. Mark H. Metcalf is a former judge on the immigration court in Miami, Fla.; under President George W. Bush he served in several posts at the Justice and Defense Departments.

On November 20, 2014, the president gave a televised nationwide address to speak about the executive actions he would take the next day allowing millions of illegal aliens to live and work in the United States for the next several years.1 Concurrent with the speech, Jeh Johnson, the Department of Homeland Security (DHS) secretary, published a series of 10 memoranda outlining and directing implementation of the various facets of the programs and policies that would constitute this sweeping and, in the view of many, unconstitutional "executive action" relating to immigration matters.

One of those policy memoranda announced an "end" to Secure Communities, a program that uses electronic matching of fingerprints to identify alien criminals in near-real time among the people arrested by police nationwide. Less noticed, but equally important, the memorandum also directed an end to the use of immigration detainers, which enable immigration agents to take custody of arrested aliens at the conclusion of their criminal justice proceedings, and upon release from custody or any sentence imposed for their crimes.2

This Backgrounder examines the legal underpinnings of detainers, their place in the statutory scheme of immigration enforcement in the interior of the United States, and their critical importance in maintaining public safety in communities throughout the country. The authors conclude that Congress should create a new process through legislation that clarifies the authority and imperative for the transfer of aliens from local to federal custody so that immigration laws can be enforced.

Key Findings:

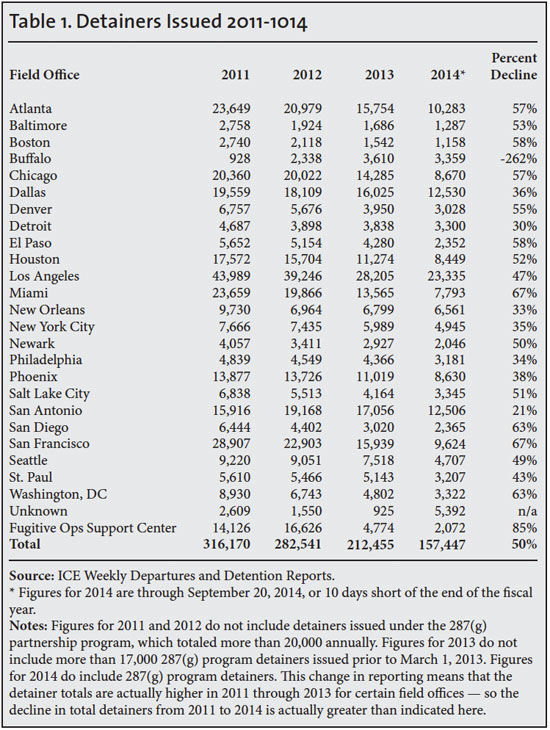

- Immigration detainers form a significant part of Immigration and Customs Enforcement (ICE) efforts against alien criminals. In federal fiscal year 2013 alone, ICE agents and officers filed 212,455 detainers with various police and correctional agencies in the United States.

- As a result of policy changes designed to inhibit use of detainers, the number issued has plummeted. In 2014, ICE filed just over 160,000 detainers.

- The Obama administration began undercutting this fundamental tool several years ago through means both overt and subtle, including modifying the language on the detainer form and issuing policy memoranda limiting the occasions in which ICE officers and agents are permitted to issue detainers against criminal aliens.

- ICE leaders have further undercut immigration enforcement efforts against alien criminals through public pronouncements made without legal foundation, characterizing compliance with detainers as voluntary, despite the weight of constitutional and legal authority indicating the contrary.

- Actions by state and local authorities that frustrate federal authority by claiming compliance is discretionary appear to be unconstitutional on their face. Specifically, the Supremacy Clause of the Constitution and its Preemption Doctrine forbid state encroachment in areas of federal exclusivity.

- Immigration detainers require state and local agencies to "hold" alien offenders potentially up to 48 hours beyond their release date. This holding period does not violate the Fourth, Fifth, and Sixth Amendments, since probable cause to believe an alien has violated federal law is set forth in the detainer itself (known as DHS Form I-247).

- The Obama administration has failed to support state and local enforcement agencies when they are sued for honoring immigration detainers, leading many such agencies to reconsider their former stances of complying with detainers.

This Backgrounder outlines steps that should be taken to restore this important tool. These steps include:

- Public statements from the Secretary of Homeland Security and Attorney General that they will initiate legal action to ensure compliance with detainers and that they will actively support localities sued for honoring detainers on the basis that issuing an immigration detainer is a prerogative and authority of the federal government. (Authors' note: We recognize the extreme unlikelihood of this administration doing anything to restore detainers to their place in the statutory and regulatory scheme, but feel obliged to leave this recommendation as a place-holder in the event that a subsequent administration comes to recognize and honor its own constitutional obligations to ensure compliance with federal law, consistent with the Supremacy Clause.)

- Adjustments to federal grant certification standards to provide federal State Criminal Alien Assistance Program (SCAAP) and other public safety or homeland security funding only to states or localities that comply with immigration detainers.

- A procedural change that encourages ICE officers to obtain, in advance, arrest warrants for aliens against whom they wish to file detainers whenever practical.

- Amendments to the Immigration and Nationality Act (INA) to clarify that compliance by state and local law enforcement with immigration detainers is required, coupled with appropriate sanctions for failure to do so.

- Establishment of state laws requiring law enforcement agencies to notify federal immigration authorities of release dates of alien criminals in their custody.

What Are Detainers and Why Are They Controversial?

Immigration detainers enable federal agencies to take custody of aliens held by state or local police agencies before their release. According to federal regulations, the detainer "serves to advise another law enforcement agency that the Department seeks custody of an alien presently in the custody of that agency, for the purpose of arresting and removing the alien."3 Usually, but not always, ICE has been the agency filing the detainer. The Border Patrol has also routinely used detainers in its dealings with sheriffs and police departments whose jurisdictions span the southwest and northern borders.

The regulations stipulate that the law enforcement agency that has custody of the alien shall hold the alien for federal immigration authorities for up to 48 hours (excluding weekends and holidays) rather than release the alien on bond, pending other local action or other factors.

Other federal agencies also use detainers as a way to hold individuals arrested by state or local law enforcement until they can be taken into custody. Individuals are routinely held by state and local agencies for the federal government for a range of offenses large and small, from being absent without leave from the armed forces, to parole and probation violation, to major felony offenses. The U.S. Marshals Service is particularly active in this regard and operates under a provision of federal law that states, "(c) Except as otherwise provided by law or Rule of Procedure, the United States Marshals Service shall execute all lawful writs, process, and orders issued under the authority of the United States, and shall command all necessary assistance to execute its duties." (Emphasis added.)4 We know of no instances where either the Marshals Service or another federal agency has characterized its detainers as "voluntary" or state and local agencies have refused to comply with them.

In recent years, opponents of immigration enforcement have sought to obstruct and interfere with ICE enforcement activities by waging a campaign to de-legitimize use of detainers, which they fully understand are a key tool for ICE. Enforcement opponents have put forth both legal and political arguments. Some have maintained that immigration agencies lack the authority to issue detainers.

While there is no section of the federal statute that spells out this authority in general terms, it cannot be said that Congress is either unaware of, or disapproves of, their use. In fact, Congress has specifically sanctioned their use by immigration authorities in the case of aliens who violate drug laws.5 Ironically, that provision was added at the insistence of federal, state, and local law enforcement officials who were agitated that agents of the Immigration and Naturalization Service (INS) — the forerunner of ICE — were not routinely filing detainers to take custody of aliens charged with possession of minor amounts of proscribed drugs such as marijuana.

Obama Administration Efforts to Undermine Detainers

The damage done to immigration enforcement by the Obama administration since 2009 cannot be overstated. While officials repeatedly claim to focus on criminal aliens, and assure Americans that lawbreakers are detained and deported, in fact immigration enforcement is in a state of collapse due to a series of policy changes known collectively as "prosecutorial discretion" and "prioritization". In practice, these policies impose severe restrictions on ICE officers as to which aliens may be targeted for deportation and exempt most illegal aliens from enforcement action. The new priorities have stipulated that only those aliens with criminal convictions, recent border crossers, prior deportees, or fugitives who absconded from deportation proceedings should be subjected to immigration enforcement.

Deportations by ICE have declined significantly over the last several years. In 2014, ICE deported approximately 100,000 aliens from the interior, which is less than half of the 237,000 aliens deported from the interior in 2009, Obama's first year in office. Criminal alien deportations also have declined significantly (by 40 percent since the peak in 2011).6 Prior to 2014, the suppression of enforcement came mainly in the form of restrictions on the types of cases that ICE officers could pursue. For example, on December 21, 2012, former ICE Director John Morton announced modifications to the standard Immigration Detainer form (Form I-247) and issued a memorandum limiting the circumstances under which ICE personnel could issue detainers.7

In recent years, most of the removable aliens encountered by ICE officers have been discovered when an arrest by local authorities triggered a notification to ICE after an electronic fingerprint match facilitated by the Secure Communities program. This improvement in federal and local law enforcement information-sharing through Secure Communities interoperability resulted in greater use of ICE detainers than ever before, as ICE became aware of many more removable aliens immediately after a state or local arrest. Needless to say, this significant improvement in ICE's effectiveness angered ethnic grievance groups and their allies in Congress and the Obama administration.

The downturn in detainers issued by ICE between the years 2011–2014, as shown in Table 1, reveals exactly how political the use of detainers became under this administration and how it has responded, to the detriment of public safety and at the expense of efficient use of limited immigration enforcement resources.

The campaign to undermine the use of detainers gained substantial momentum in February 2014, when Dan Ragsdale, then acting head of ICE,8 advised in response to an inquiry from a group of members of Congress on behalf of confused local law enforcement agencies, that "While immigration detainers are an important part of ICE's effort to remove criminal aliens who are in federal, state, or local custody, they are not mandatory as a matter of law. As such, ICE relies on the cooperation of its law enforcement partners in this effort to promote public safety." (Emphasis added.)

Ragsdale's assertion, which was backed by no legal rationale whatever, was momentous. Reportedly, staff in both the operations and legal divisions of ICE had put forth a different legal opinion, consistent with ICE's long-established position that it expected other law enforcement agencies to honor and comply with its detainers, which Ragsdale overrode in formulating his letter. Their objections to his response were founded not just on institutional needs and policy, but also on federal regulation: 8 CFR 287.7(d), which says:

Upon a determination by the Department to issue a detainer for an alien not otherwise detained by a criminal justice agency, such agency shall maintain custody of the alien for a period not to exceed 48 hours ... in order to permit assumption of custody by the Department."9 (Emphasis added.)

Ragsdale's move did not go unnoticed, including by jurists in the course of civil lawsuits filed by aliens and their pro bono attorneys at the American Civil Liberties Union (ACLU) and elsewhere, against ICE and against those state and local law enforcement agencies who honor the detainers. The federal Third Circuit Court of Appeals recently held that detainers were voluntary (overruling a district judge's finding prior to Ragsdale's policy change), thus permitting a civil suit against a county jail to go forward.10

More telling is how ICE treated its "law enforcement partner" in this instance. It settled with the plaintiffs and deserted the jailer and sheriff's offices, declining even to file an amicus curiae ("friend of the court") brief, although the fundamental error in the case — filing a detainer against a citizen — originated with ICE itself. Nor was this the first time that ICE engaged in a strategy of "cut and run" from one of its erstwhile law enforcement partners. The same thing happened in Tennessee in 201211 and just recently in Oregon, where a federal magistrate ruled the Clackamas County jail's strict compliance with an ICE detainer was unconstitutional because, it said, compliance with such detainers is voluntary.12

The adverse effect of these decisions, especially when combined with ICE's indifference toward its partner agencies, began to accumulate. Various law enforcement agencies nationwide issued statements indicating they would decline compliance with some or all immigration detainers. The number has since risen to more than 300 police and sheriff's departments. While some of these agencies are in small jurisdictions where law enforcement agencies encounter criminal aliens less frequently, others include major metropolitan areas such as Chicago and New York, where the number of aliens held in a year's time reaches into the thousands. The risk — and the reality — is that arrested criminal aliens are being released into American neighborhoods before their identities can be confirmed and federal custody assumed.

The campaign to undercut detainers achieved its ultimate goal when DHS Secretary Johnson issued his policy memorandum on November 20 ordering an end to the filing of detainers except in extraordinary circumstances. Until then, even while in decline, detainers had been the primary tool used to notify state and local law enforcement and corrections agencies that an alien in their custody was subject to removal from the United States.

Most dismaying is that in a footnote to his memorandum, the secretary alluded to the recent court decisions and suggested that use of detainers might violate the Constitution. First, the administration actively worked to undercut the detainer authorities of its own immigration agencies, limiting their use by policy and then without legal foundation declaring them to be voluntary. Now, in a classic example of disingenuous circularity, the administration uses the court decisions (which in turn were exercising "due deference" to ICE's baseless interpretation of voluntariness), in order to justify scrapping detainers in their entirety.

What is more, opponents of detainers have chosen to misread the general import of the recent cases. One of the lawsuits was filed because ICE mistakenly lodged a detainer against a United States citizen, not an alien. Another lawsuit was filed when an alien was held significantly longer than 48 hours beyond his release date (what the regulation requires). Certainly such particular cases implicate the Fourth Amendment — but they do not implicate detainers generally.

Over the course of time, a series of court rulings established that state and local authorities may detain or arrest individuals for violations of federal immigration law, as long as the arrest is supported by reasonable suspicion or probable cause and is authorized by state law.13 Additionally, a 2002 Department of Justice (DOJ) opinion came to the same conclusion. Some analysts believe that the prior rulings and the DOJ opinion were significantly delimited by the 2012 Supreme Court decision in the case of Arizona v. United States.14 It is beyond the purview of this report to fully explore that decision, but three things can be said with certainty:

- The court has still left room for state and local police action in the arena of immigration enforcement, provided that it is consonant with federal laws and regulations and occurs in the course of lawful state enforcement programs.

- Congress can open the door to additional state and local participation and initiatives by exercising its constitutional prerogatives in the legislative arena; specifically through statutes, statements of congressional intent, and establishment or endorsement of cooperative enforcement programs in the course of its legislative and appropriations activities.

- In the words of the Congressional Research Service, "the federal government also has the power to proscribe activities that subvert [the legislatively established immigration] system." This latter point is extremely important in the context of state and local activities (such as passage of laws, regulations, and policies directing police and sheriff's offices to ignore immigration detainers), which fundamentally impede effective immigration law enforcement against alien criminals in the interior of the United States, clearly contrary to both implied and express congressional intent.15

In general, federal law, regulations, and policy encourage state and local cooperation with federal immigration authorities. For instance, an unambiguous provision of the INA states, "Notwithstanding any other provision of federal, state, or local law, no state or local government entity may be prohibited, or in any way restricted, from sending to or receiving from the Immigration and Naturalization Service information regarding the immigration status, lawful or unlawful, of an alien in the United States."16

In nearly verbatim language, another provision of the INA prohibits state or local governments preventing their employees from communicating freely with immigration officials: "[A] federal, state, or local government entity or official may not prohibit, or in any way restrict, any government entity or official from sending to, or receiving from, the Immigration and Naturalization Service information regarding the citizenship or immigration status, lawful or unlawful, of any individual."17 An additional subsection of that same provision also stipulates that "The Immigration and Naturalization Service shall respond to an inquiry by a federal, state, or local government agency seeking to verify or ascertain the citizenship or immigration status of any individual within the jurisdiction of the agency for any purpose authorized by law, by providing the requested verification or status information."18 (Emphasis added.)

One wonders: if the "shall" in the regulation relating to detainers is to be disregarded so cavalierly. Does this mean that the above-cited language requiring the INS (or its successor agencies) to provide information or assistance to other federal, state, or local agencies may also be disregarded? Of course not, but under this administration, use of the word "shall" seems to have taken on an elastic Through the Looking Glass quality.19

Other evidence of congressional intent to establish a collaborative environment between police and immigration enforcement agencies can be found in the statutory language creating certain types of local-federal partnerships. A notable example includes a program authorizing cross-designation of state or local officers to enforce immigration laws under Section 287(g) of the INA, commonly known as the "287(g)" program.20 The language of Section 287(g) also goes so far as to make clear that exchanges of information between immigration authorities and other federal, state, or local entities cannot be limited to, or require, formal agreements.

Another significant example of the congressional expectation of cooperation on immigration law enforcement matters, among and between federal, state, and local officials, can be found in Section 103(a) of the INA, which permits the Attorney General (superseded by the Secretary of Homeland Security by the Homeland Security Act) to permit state and local officers to exercise immigration law enforcement functions in the event of an actual or imminent mass migration of aliens.21 Additional language in that same section also permits the DHS secretary "to enter into a cooperative agreement with any state, territory, or political subdivision thereof for the necessary construction, physical renovation, and acquisition of equipment, supplies, or materials required to establish acceptable conditions of confinement and detention services in any state or unit of local government that agrees to provide guaranteed bed space for persons detained by the service."22

DHS agencies have established more than a dozen formal cooperative programs in addition to the 287(g) program described above, including the Criminal Alien Program, which provides for ICE agents to interview incarcerated aliens to determine removability prior to their release, and the Law Enforcement Support Center, which is a 24/7 call center that enables state and local officers to inquire about the immigration status of individuals they encounter. Virtually all of these programs have received congressional endorsement, if not always through specific statutory provisions such as those enumerated above, then certainly through the appropriations process.23

Some legal experts have argued credibly that those jurisdictions that have changed their policies recently to end compliance with ICE detainers are misinterpreting the court rulings on detainers, and mistakenly relying on ideologically influenced assertions from the ACLU, which has aggressively sent "notices" to police and sheriff's offices and prosecutor's offices, advising them of grave constitutional issues with an implicit threat of lawsuits should these organizations choose to continue complying with detainers.24 For instance, contrary to what many sanctuary jurisdictions have claimed, the Oregon magistrate did not hold that ICE detainers need to be accompanied by a judicial warrant.25

Federal Laws and Regulations Trump State Laws and Regulations

Detainers are issued pursuant to federal regulations, which in turn rely on provisions in the INA authorizing officers and agents to make arrests with or without warrant for violation of the immigration laws.26 The Supremacy Clause27 of the Constitution and its Preemption Doctrine28 forbid state encroachment in areas of federal exclusivity. The federal government possesses inherent sovereign powers in matters of immigration and immigration enforcement. The Supremacy Clause and the Preemption Doctrine assure that federal law prevails over state and local measures whenever a conflict arises between the two.29 Federal immigration law is no different.

Over no subject, in fact, is federal jurisdiction so complete as it is in immigration.30 Still, the federal system does not work in a vacuum. Its success depends upon compliance with federal prerogatives31 and comity32 among state, local, and federal jurisdictions that complement their various missions.

But it is precisely in the opposite direction that many sub-federal state and local agencies now proceed with the active encouragement of Obama appointees who have sought to redefine the meaning of federal laws without regard to their plain terms and clear intent.33 If localities alone may decide whether to hold a suspect after receiving notice of an immigration detainer, then federal supremacy in immigration enforcement is now subject to unilateral exercises of previously unacknowledged state prerogatives — prerogatives that have the effect of nullifying federal statutes passed by Congress and signed into law by the president — a result no one can believe is either intended or acceptable, and which flies in the face of the Supreme Court's Arizona decision. As Justice Kennedy observed, writing for the majority, "[S]tate laws are preempted when they conflict with federal law. ... This includes cases where 'compliance with both federal and state regulations is a physical impossibility,' and those instances where the challenged state law 'stands as an obstacle to the accomplishment and execution of the full purposes and objectives of Congress.'"34

Federal jurisdiction over immigration in all its expressions was, until the Ragsdale letter, presumed exclusive and nonpareil. However much Mr. Ragsdale insists that states may refuse a detainer, his argument fails under the weight of precedent proving him wrong.35

In fact, federal supremacy in immigration, though frequently challenged, was not relinquished on such a scale until the Obama administration. His presidency has not changed the wording of federal statutes or a century and a half of Supreme Court precedent, but rulemaking and policy under his administration have turned immigration enforcement upside down and, in turn, set criminal aliens free by the thousands and left American neighborhoods less safe.36

The U.S. Supreme Court has never sanctioned unilateral expansion of state immigration enforcement into a historically federal domain; rather, the court has closely scrutinized state intrusion into federal immigration law.37 In the same way a state or locality cannot assume those immigration enforcement powers that are forbidden it by the Constitution, so it also cannot refuse the demands of an immigration detainer.

In addition to federal supremacy and preemption of state and local laws and policies, any careful, reasoned analysis of the issue must examine the interplay between refusal by state officials to honor detainers on one hand and, on the other, the provisions of federal law relating to harboring of illegal aliens and shielding them from detection — a felony violation.38 The provision states in pertinent part:

(a) Criminal penalties

(1)

(A) Any person who—

...

(iii) knowing or in reckless disregard of the fact that an alien has come to, entered, or remains in the United States in violation of law, conceals, harbors, or shields from detection, or attempts to conceal, harbor, or shield from detection, such alien in any place, including any building or any means of transportation ... shall be punished as provided in subparagraph (B).

The harboring and shielding-from-detection provisions of the statute are not limited to private individuals. If a citizen may be charged with a felony for this action, then how can state or local officials be less culpable, particularly when they are law enforcement officers who are generally understood to be held to a higher standard where compliance with the law is concerned?

The quagmire in which ICE now finds itself is in large measure of its own making. It has severely limited the circumstances in which a detainer may be issued; it has greatly reduced the number and type of aliens who may be detained; it has spread the notion that honoring detainers is purely voluntary among its "partners"; and then it has consistently abandoned those partners when lawsuits are filed; and, of course, by having made a public assertion that honoring detainers is a matter of choice, ICE has given jurists who are ideologically disposed to be skeptical of immigration enforcement a very large hook to hang their hats on through the "due deference" doctrine by which courts give great leeway to executive agencies in the interpretation of their own rules.39 (Ironically that self-same "due deference" could and should be applied to ICE's actual regulation, not the legally dubious correspondence from officials such as Ragsdale, which holds no place in the regulatory scheme.)

But can ICE (or, more specifically, Ragsdale when he was acting as agency head) be trusted with the "detainers are voluntary" interpretation? Quite possibly not. To those who follow such matters, it is disturbingly similar to the "state and local agencies can opt in or opt out" refrain used by ICE leaders in public statements and official documents, including letters to Congress, during the roll-out of their Secure Communities program. Ultimately the agency, and its bosses at DHS, had to eat those words. Worse, we now know that ICE and Department of Homeland Security (DHS) officials conspired with the acting Inspector General to cover up their deception even as the IG's office was being charged with investigating the missteps, misstatements, and ineptitude exhibited in the way Secure Communities was handled.40 Why should we now believe that Mr. Ragsdale has any more credibility on the detainers issue than he did when acting as one of Mr. Morton's confidantes and advisors about Secure Communities?

Public Safety Impact of Non-Cooperation Policies

Until the campaign to undermine immigration detainers gained traction not only from open borders groups, but from the very leaders charged with immigration enforcement, the detainers formed a critical part of ICE's law enforcement efforts against alien criminals. In federal fiscal year 2013 alone, ICE agents and officers filed 212,455 detainers with various police and correctional agencies in the United States.41

The combination of local obstruction of ICE and ICE's self-imposed limits on enforcement priorities had already begun before Johnson's decision to terminate their use. According to a recent report from the Syracuse University Transactional Action Clearinghouse (TRAC), ICE detainers have dropped 39 percent since 2012. Interestingly, the report tells us that, "TRAC shared its findings with ICE and asked the agency for insights into what was driving this downward trend. However, ICE declined to comment on why its agents were issuing fewer detainers."42

Ironically, in a recent media article published by NJ.com — published prior to the president's executive action speech and promulgation of the Johnson memorandum — ICE was much less reticent about its dissatisfaction with state and local jurisdictions ignoring their detainers. An ICE spokesman is quoted in the article as saying, "When serious criminal offenders are released to the streets in a community, rather than to ICE custody, it undermines ICE's ability to protect public safety and impedes us from enforcing the nation's immigration laws. ... Jurisdictions that ignore detainers bear the risk of possible public safety risks."43

But the problem of ignoring detainers is not just about statistics, and it is far more than a matter of workload completion for ICE agents and officers in pursuing their mission, however significant those matters are. Fundamental governmental interests are involved, including community safety, officer safety, efficient use of taxpayer funds, and maintenance of an effective regimen of due process within the immigration system established by Congress:

- When sheriffs or police turn a suspect loose rather than hold him on the detainer filed, law-abiding members of the community are at risk should he re-offend (and there are many, often egregious, instances of such alien recidivists victimizing additional members of the public).44

- If ICE officers are obliged to go out and seek the individual once he has been released, they, too, are at greater risk of injury than if receiving him directly from local law enforcement officers in the secure constraints of a jail setting — especially since the alien offender at the point of release, notwithstanding the detainer, is likely to know that they are aware of and looking for him.

- Furthermore, the time and energy wasted trying to track down and re-apprehend that alien after local police have released him equates to limited officer resources and public monies not available to do equally important immigration enforcement work elsewhere in an already overburdened system. Confronting this reality pokes a large hole in the administration's argument that its executive actions are for the purpose of enhancing public safety and shepherding scarce resources.

- What is more, the alien may not in fact be re-apprehended until after he has committed another crime, quite possibly a violent felony: "According to the Government Accountability Office, in 2009, the average incarcerated alien had seven arrests and committed an average of 12 offenses."45 A Congressional Research Service study commissioned by the House Judiciary Committee found that 26,412 aliens out of 159,286 released by ICE in a 2.5-year time period went on to commit 57,763 new crimes. These crimes included 8,500 DUIs, 6,000 drug offenses, and more than 4,000 major criminal offenses such as murder, assault, rape, and kidnapping.46

- It is also important to understand that "immigrant offenders often fail to follow the rules — that is, attend court like everyone else. Immigration court records from 1996 through 2012 show 76 percent of 1.1 million deportation orders were issued against those who evaded court. These evasions compose the greatest source of unexecuted deportation orders in the immigration court system. Not even a quarter of those free pending trial — some 268,000 — actually came to court and finished their cases."47

- Finally, there is the sobering fact that there are already nearly 900,000 alien absconders and fugitives at large in the country — up from half a million a mere three years ago.48 Each alien released despite the filing of a detainer, when multiplied by the thousands of sheriff's offices and police departments throughout the United States, adds significantly to that number, and puts the public at greater risk.

Something must be done to stop the legal oblivion into which detainers have been thrown. But what? Following are a series of common-sense recommendations.

Recommendations

The Executive Branch. (Authors' note: As indicated before, we acknowledge that our recommendations go in a direction completely contrary to that of this administration, meaning there is no chance whatever that they will adopt our suggestions, but we are constrained to raise them nonetheless in the interest of posterity and in the hope of a future chief executive who recognizes his constitutional and statutory responsibilities.) The administration has repeatedly claimedthat it is interested in prioritizing the enforcement of immigration laws away from run-of-the-mill illegal aliens and toward criminal offenders. If administration leaders and cabinet heads wish Congress and the public at large to believe this, they should be working vigorously to protect key law enforcement techniques from the kind of blunting that the use of detainers has taken in the past couple of years instead of contributing to their demise as a tool. To that end:

- DHS Secretary Jeh Johnson should formally disavow the legal assertion made in Ragsdale's letter and revisit his decision to end the use of detainers based on flawed legal reasoning.

- The DHS Secretary and the Attorney General should jointly issue a notice in the Federal Register publicly stating their intention to initiate legal action in U.S. District Court to obtain orders enjoining state and local governments from ignoring detainers in each and every jurisdiction where that takes place, all the way to the Supreme Court if need be. They should also assert, however, that the federal government's position is that, by honoring those detainers, state and local governments are not subject to tort suits because the decision-making inherent in deciding to file, or not file, a detainer rests with federal immigration authorities.

- The two cabinet members should also declare changes to the certification process for the State Criminal Alien Assistance Program (SCAAP) — a program designed to reimburse state and local enforcement agencies for costs associated with the arrest and confinement of illegal aliens — which would preclude those agencies from seeking SCAAP funds when they initiate policies that obstruct federal efforts to locate, identify, apprehend, and remove those criminals. This requires no change to the existing statute to accomplish; it simply requires the will to do so. The fund is administered by the Justice Department's Bureau of Justice Assistance (BJA), but relies on ICE certification of lists of incarcerated aliens provided to BJA by states and localities. Simply declining to certify lists of incarcerated aliens submitted by jurisdictions that refuse to comply with detainers would result in them receiving no SCAAP funds.49

- ICE officers should, whenever possible, begin the practice of procuring warrants of arrest for aliens against whom they intend to file detainers. Those warrants of arrest should be provided to the law enforcement agency at the time the detainer is filed. While such warrants are civil in nature — because deportation proceedings are themselves civil proceedings — they clearly signal to state and local agencies that ICE is following a procedure prescribed by federal law and regulation, and that cause exists for arrest and initiation of deportation proceedings. We note that this is not required by law, which clearly provides for warrantless immigration arrests. However, we recognize the importance of signaling to state and local jurisdictions that, whenever circumstances permit, a deliberative process was undertaken that has resulted in a probable cause finding that an individual in custody of the state or local agency is an alien subject to removal proceedings whom federal authorities wish to take into their own custody in order to initiate those proceedings, consistent with the provisions of the INA.50

Some ICE offices have begun this practice. As expected, various legal advocacy groups have initiated a campaign against their use, arguing that only "judicial" warrants should be accepted by local law enforcement agencies. For example, in collaboration with advocacy groups, the Secretary of the Massachusetts Executive Office of Public Safety (EOPS) — a state executive branch agency (controlled by the governor) argued against the acceptance of ICE warrants in a memorandum issued to the Massachusetts State Sheriffs Association.51 The memorandum was replete with specious logic, including the assertion that warrants not issued by a judge, such as immigration warrants, have no force and effect and therefore should not affect decisions to comply or, more to the point, refuse to comply, with detainers. Interestingly, using this logic, parole violation warrants issued by the Massachusetts Parole Board — a subordinate administrative agency of EOPS — would also fail to pass legal muster. The memorandum was quickly disavowed by Governor Deval Patrick, but the arguments have started to find their way into other venues despite the obvious flaws in the logic. Likewise, using this logic, police and sheriff's departments should refuse to hold AWOL or deserting soldiers for military police, because they are handled under Article 85 the Uniform Code of Military Justice (UCMJ), which operates outside of the federal criminal justice system.

State and Local Governments. State legislatures should expeditiously draft and pass to their governors for signature bills requiring state and local law enforcement agencies to notify federal immigration authorities of the release dates and times for all alien criminals within their custody.

There are also a number of ways in which state and local governments can protect themselves from legal action, while at the same time cooperating with federal immigration enforcement initiatives and protecting their communities from alien recidivist offenders.

State and local correctional, police, and sheriff's departments should initiate a dialogue with ICE whose purpose is to negotiate a memorandum of agreement (MOA) outlining the parameters of the law enforcement partnership. The memorandum of agreement should ideally contain the following provisions:

- An unambiguous statement from ICE that determinations about the filing of detainers or notices of action, requests for release dates, or other information relating to deportable aliens are based on federal immigration law, for which it is solely responsible.

- A commitment by ICE to take custody of aliens within the timeframe specified in federal regulations at 8 CFR 287.7 whenever a detainer is filed, which commitment should be included in the memorandum of agreement for clarity of understanding.

- Local training sessions by ICE for jail personnel involved in the handling of immigration detainers so that they will understand the various forms and their uses, which in their present incarnation are sometimes informational only and sometimes a request to detain.

- Specifically designated points of contact for both parties for maintenance and upholding of the memorandum of agreement, and additional points of contact available on a 24-hour/7-day-weekly basis for critical problem resolution.

- Acknowledgement between the parties that in order for the correctional, police, or sheriff's department to comply with an ICE detainer, it must be accompanied by a Warrant for Arrest of Alien, except in exigent circumstances, which should be specified.

- Agreement that in the event of a lawsuit against the police or sheriff's office based on honoring of an ICE detainer, ICE will provide all reasonable and necessary legal assistance, including "friend of the court" briefs acknowledging its responsibility for detainer decision-making.

- Participation of the police or sheriff's office in the ICE 287(g) program, in which designated sheriff's deputies and/or jail officers are trained and cross-designated as immigration officers (at ICE expense), giving them access to ICE databases and information, and the authority to issue certain law enforcement documents, including detainers. (Note that such documents are issued under the supervision of ICE managers, thus ensuring that ICE remains responsible for the decision-making process.)

Congress. A multiplicity of reasons exist to believe that many of the steps recommended above will not take place given the administration's abysmal track record, and lack of will, for sustaining any capacity for interior immigration enforcement. This being the case, the ultimate resolution may rest with Congress to craft statutory language that breaks the impasse.

Almost all of the members of Congress who have argued for amnesty or "a path to citizenship" have concurrently asserted that they draw the line at aliens who break criminal laws. It's time to prove the sincerity of such claims by doing what is necessary to require the law enforcement agencies of states and localities to surrender to ICE those aliens who are subject to ICE detainers. Such actions could include:

- Advancing the SAFE Act, which in the 113th Congress was approved by the House Judiciary Committee. Provisions in this bill explicitly 1) extend to state and local law enforcement officers the same qualified immunities extended to federal officers; and 2) authorize state and local agencies to comply with detainers filed by federal immigration authorities.52 However, the language contained in those sections should be revisited in light of recent court decisions. At minimum, the language "authorizing" agencies to honor detainers should be rewritten to require that they comply with detainers.

- Congress should adopt, perhaps via a new Section 287A of the INA, a different paradigm for immigration processes that is more closely aligned to the notion of writs exercised by courts at all levels of government. The legislation would authorize certain federal immigration officials (to be designated by regulation) to issue and serve upon state and local agencies an "Order to Detain and Produce Alien". Such an order would be enforceable in the United States District Courts by means of a show cause order from the presiding judge requiring state or local agency which fails or refuses to comply to explain why it has failed to do so.

- Considered dispassionately, as important as detainers are, they are merely the means to an end. What the immigration authorities ultimately wish is to take custody of the alien. Creating a specific statutory authority by which federal immigration officers may require state and local agencies to detain and produce the body provides both the means and the end needed to accomplish their duties. (An example of such possible legislation is attached as Appendix 1 to this Backgrounder.)

- Congress should also act to statutorily amend the State Criminal Alien Assistance Program, if the Attorney General and Secretary of DHS fail to do so, to ensure that state and local governments cannot be safe havens for criminal aliens on the one hand, while demanding federal dollars to reimburse them for the costs associated with arrest and incarceration on the other. (An example of such possible legislation is attached as Appendix 2 to this Backgrounder.)

- Finally, whether moving toward the kind of solution contained in the SAFE Act, or toward a new paradigm more closely aligned to the notion of writs to produce the body, a "hold harmless" provision must also be crafted to protect state and local agencies from lawsuits when in good faith they honor detainers filed by federal officers. At present, state and local officers enjoy such protection on an individual basis when acting in a cross-designation capacity under Section 287(g). A new, expanded provision written into the law could encompass the "hold harmless" premise to an entire state or local organization when it honors decisions to file immigration detainers under authority of federal immigration laws.

Conclusion

Immigration detainers are a critically important a tool in the ICE mission to apprehend alien criminals and protect the public safety. Preserving their use, defending them against continued attack in the courts, and establishing the means and requirement for state and local enforcement agencies to honor federal immigration laws should be a shared priority for all of the branches of the federal government.

Appendix 1: Model Language for a New INA Section 287A [8 U.S. Code § 1357a] – Order to Detain and Produce Alien

(a) Authority to Issue an Order to Detain and Produce Alien

Any officer or employee of the Service authorized under regulations prescribed by the Secretary to issue warrants of arrest or notices to appear in removal proceedings shall have power to issue an order to detain and produce an alien who is in the custody of another federal, state, or local law enforcement, correctional, mental or physical health, or social service agency for the purpose of taking custody of such an alien to initiate removal proceedings, or to effect the removal of an alien under an order of removal.

(b) Obligations and Authorities of Receiving Agencies

(1) Upon receipt of such an order, said agency is authorized and required to maintain custody of the alien for a period of up to 14 calendar days after the alien has completed the alien's sentence under Federal, State or local law, or is otherwise ready for release, in order to effectuate the transfer of the alien to Federal custody.

(2) Should the agency in original receipt of the order transfer the alien to another agency for purposes of serving a sentence of incarceration, or for other purposes including medical treatment, it shall (A) promptly, but in no event later than 24 hours, notify the officer who issued the Order of the particulars of the transfer, and (B) serve upon the agency assuming custody a copy of the original order.

(3) The agency which assumes custody shall be equally liable to comply with the requirement to detain and produce as if it were the recipient of the original order.

(4) State and local law enforcement and correctional agencies are authorized to issue a detainer that would allow aliens who have served a sentence of incarceration under State or local law to be detained by the State or local prison or jail until the Secretary can take the alien into custody provided that notice of the detainer filed on behalf of the Secretary is transmitted within 24 hours to the nearest Immigration and Customs Enforcement office along with identifying biographic and offender information required to make a determination of alienage and removability. That office shall respond to the state or local agency making the notification within 24 hours, either confirming the detainer or ordering its withdrawal.

(c) Immunity of Receiving Agencies

No agencies nor officers or employees of agencies which have received an order to detain and produce an alien shall be liable for damages under law as a result of complying with such an order.

(d) Failure or Refusal to Comply with Order to Detain and Produce Alien

If a state or local agency refuses or fails in its duty to comply with an order to detain and produce an alien, the United States District Court shall, upon request of the United States Attorney for that district, issue an order requiring the agency to show cause why it did not do so and, upon a finding that the failure was intentional, shall hold the agency in contempt. Whether the failure to comply was intentional or negligent, it shall be in the Court's power to issue any such orders as are necessary to enjoin the agency from conduct that results in future refusal or failure.

(e) Means of Service and Content of Order.

(1) An order to detain and produce an alien may be served in person or by electronic means.

(2) The order to detain and produce an alien shall contain at minimum the following information:

(A) The name, date and place of birth of the alien, including known aliases or alternately claimed dates and places of birth;

(B) A brief statement of the grounds of removability, which shall not prevent superseding allegations and grounds from being used in any future charging document;

(C) The title and address of the agency receiving the order to detain and produce;

(D) The name and title of the officer issuing the order to detain and produce;

(E) The specific point of contact, and means by which the receiving agency should initiate that contact for purposes of notifying of an impending release, or of transfer of the alien to a subsequent agency; and

(F) A clear statement of the affirmative obligation of the receiving agency to comply with the order, and the consequences for refusal or failure to comply.

Appendix 2: Model Language for a New INA Section 287B [8 U.S. Code § 1357b] – Ineligibility for Federal Funding to States or Localities which Fail to Cooperate in Immigration Enforcement Efforts

(a) Notwithstanding any other provision of law, if the government of a state, tribe, territory, or possession of the United States, or a political subdivision of any of the aforementioned, or the District of Columbia,

(1) refuses or declines to honor Orders to Detain and Produce an Alien filed by Homeland Security officers or agents against individuals known or suspected to be undocumented or criminal aliens subject to removal from the United States, or

(2) enacts into law, or establishes by executive order, administrative regulation or policy, restrictions upon access to prisoners or detainees by federal officials enforcing the immigration laws of the United States, or upon cooperation with those federal officers by state and local law enforcement or correctional officers, or

(3) refuses or declines to exercise its authority to override the stated intention of one of its political subdivisions to engage in the conduct described in Paragraphs (1) or (2) above, neither said government nor any of its political subdivisions shall be eligible to receive funding from the Department of Justice State Criminal Alien Assistance Program.

(b) For purposes of this act, refusal or declination of a government to exercise its authority as described in Section (a) includes, but is not limited to, statute, ordinance, order, rulemaking, policy, standard practice or directive on the part of a legislative or executive body or officer.

(c) Within 30 days of enactment of this act, the Department of Homeland Security shall:

(1) Prepare a comprehensive listing of all governments of states, tribes, territories or possessions, or political subdivisions thereof, or of the District of Columbia, which meet the ineligibility requirements described in Subsection (a) above;

(2) Send a notice to each government so listed informing it of the provisions of Subsection (a), asking that government whether it wishes to state affirmatively for the record its willingness and intent to honor Orders to Detain and Produce an Alien, or to repeal any laws, or withdraw any executive orders, regulations or policies constituting a basis for ineligibility, and advising said government that failure to receive an affirmative response within 30 days of the date of the notice will result in ineligibility for and withdrawal of State Criminal Alien Assistance Program funding ; and

(3) Send a concurrent notice to each state, territory or possession in which a political subdivision has evidenced its unwillingness to participate, informing it of the provisions of Paragraph (a)(3), asking the state, territory or possession whether it wishes to exercise its authorities to override the stated intentions of the political subdivision, and advising that failure to receive an affirmative response within 30 days of the date of the notice will result in the state, territory or possession also becoming ineligible for State Criminal Alien Assistance Program funding.

(d) Upon expiration of the times described in Subsection (c), and in no event to exceed 30 days thereafter, the Department of Homeland Security shall transmit to the Bureau of Justice Assistance in the Department of Justice a listing of the governments of any state, territory, possession, or political subdivision thereof, or of the District Columbia, which is ineligible for State Criminal Alien Assistance Program funding. Said listing shall be final and determinative.

(e) Subsequent to the initial notices and listing described in Subsections (c) and (d), within 30 days of being advised or becoming aware of a government refusing or declining to honor Orders to Detain and Produce an Alien, or to permit law enforcement cooperation with immigration enforcement efforts, or to override the actions of a political subdivision in refusing to honor Orders to Detain and Produce an Alien or to permit law enforcement cooperation with immigration enforcement efforts as described in Subsection (a), the Department of Homeland Security shall follow the same procedures and timeframes outlined in those sections to:

(1) Inform said government that its actions will render it ineligible to receive funding,

(2) Ascertain whether that government is willing to reconsider and to affirm its willingness to honor Orders to Detain and Produce an Alien, or cooperate with immigration enforcement efforts,

(3) Advise the state, territory or possession (if the uncooperative government is a political subdivision) of the consequences of failure to exercise its authorities to override that government's decisions, and

(4) Notify the Bureau of Justice Assistance of any governments which, having been given the opportunity, refuse or to decline to affirm, or override political subdivisions, thus rendering themselves ineligible for funding.

(f) Congressional Reports

(1) 120 days after enactment,

(A) The Department of Homeland Security shall provide a report to the Congress outlining what steps have been taken to implement the provisions of this act. The Department shall append to its report a copy of the list described in Subsection (d) above.

(B) The Bureau of Justice Assistance shall provide a report to the Congress outlining the steps taken to implement the provisions of this act, and append to its report a list of governments that have been debarred from receipt of State Criminal Alien Assistance Program funding.

(2) Within 120 days of the commencement of each new fiscal year,

(A) The Department of Homeland Security shall provide a report to the Congress of its activities to monitor state, territories, possessions and their political subdivisions to ensure compliance with this Section, appending to its report a list of governments found not to be in compliance during the prior fiscal year, and

(B) The Bureau of Justice Assistance shall provide a report to the Congress of its activities to ensure compliance with this Section, and append to its report a list of governments that have been debarred from receipt of State Criminal Alien Assistance Program funding during the prior fiscal year.

End Notes

1 The Washington Post, "Transcript: Obama's immigration speech" s, November 20, 2014.

2 U.S. Department of Homeland Security website, "Fixing Our Broken Immigration System Through Executive Action - Key Facts". (See, specifically, "End Secure Communities and Replace it with New Priority Enforcement Program".)

3 See 8 CFR 287.7.

4 See 28 U.S.C. 566(c).

5 See 8 USC 1357(d).

6 See Jessica M. Vaughan, "ICE Enforcement Collapses Further in 2014", Center for Immigration Studies, October 2014; and the Immigration and Customs Enforcement report, "Fiscal Year 2014 ICE Enforcement and Removal Operations Report", as cited in the Los Angeles Times, December 4, 2014.

7 Immigration Legal Resource Center, "Revised 2012 ICE Detainer Guidance: Who It Covers, Who It Does Not, and the Problems That Remain", December 12, 2012.

8 Ragsdale is now deputy director of ICE. However, at the time Ragsdale termed detainers as "voluntary", he was de facto head of the agency.

9 8 CFR, 287.7, op cit. See, particularly, subsection (d) "Temporary detention at Department request".

10 Dan Cadman, "Bad Cases, Bad Case Law: The Third Circuit rules that honoring ICE detainers is discretionary", Center for Immigration Studies blog, February 7, 2014.

11 W.D. Reasoner, "Leaving a Local Law Enforcement Partner in the Lurch: With Friends Like ICE, Who Needs Enemies?" Center for Immigration Studies blog, September 4, 2012.

12 Flashalertnewswire.net, "Summary of Judge Stewart's Opinion and Order on Summary Judgment". See also Miranda-Olivares v. Clackamas County, et al., U.S. District Court for the District of Oregon, Case No. 3:12-cv-02317-ST.

13 Michael John Garcia and Kate M. Manuel, legislative attorneys, "Authority of State and Local Police to Enforce Federal Immigration Law", Congressional Research Service, September 10, 2012.

14 Supreme Court of the United States, Arizona et al. v. United States, No. 11–182. Argued April 25, 2012, decided June 25, 2012.

15 Michael John Garcia and Kate M. Manuel, op. cit.

17 8 U.S.C. 1373. See subsections (a) and (b).

18 8 U.S.C. 1373. Op. cit. See subsection (c).

19 See Lewis Carroll, Through the Looking Glass: "'When I use a word,' Humpty Dumpty said in rather a scornful tone, 'it means just what I choose it to mean — neither more nor less.' 'The question is,' said Alice, 'whether you can make words mean so many different things.' "

20 8 U.S.C. 1357(g). Unfortunately, as with Secure Communities, the Obama administration, responding to open borders advocates, has also eviscerated this previously robust nationwide program.

23 In fact, the now-defunct Secure Communities program was predicated upon language found in Public Law 110-329, which, in addition to providing the outlay of funds required for start-up and eventual national implementation, established a requirement of quarterly reports to the House and Senate committees on appropriations. See "U.S. Immigration and Customs Enforcement Salaries and Expenses" within Title II of Division D of the Consolidated Security, Disaster Assistance, and Continuing Appropriations Act, 2009, 122 STAT. 3594, enacted in September of 2008. Both the funding and the reporting requirements continued in appropriations acts passed by Congress and signed into law by the president every year thereafter. For this reason, the decision by the secretary to discontinue the program appears to fly in the face of congressional intent.

24 See, for example, this letter to Georgia sheriffs.

25 Ibid.

26 See 8 U.S.C. 1226 and 8 U.S.C. 1357. Note, particularly 8 U.S.C. 1357(d), discussed earlier in this paper, which states:

- Powers of immigration officers and employees…

(d) Detainer of aliens for violation of controlled substances laws

In the case of an alien who is arrested by a Federal, State, or local law enforcement official for a violation of any law relating to controlled substances, if the official (or another official)—

(1) has reason to believe that the alien may not have been lawfully admitted to the United States or otherwise is not lawfully present in the United States,

(2) expeditiously informs an appropriate officer or employee of the Service authorized and designated by the Attorney General of the arrest and of facts concerning the status of the alien, and

(3) requests the Service to determine promptly whether or not to issue a detainer to detain the alien, the officer or employee of the Service shall promptly determine whether or not to issue such a detainer. If such a detainer is issued and the alien is not otherwise detained by Federal, State, or local officials, the Attorney General shall effectively and expeditiously take custody of the alien.

27 Article VI of the U.S. Constitution states: "This Constitution, and the Laws of the United States which shall be made in Pursuance thereof; and all Treaties made, or which shall be made, under the Authority of the United States, shall be the supreme Law of the Land; and the Judges in every State shall be bound thereby, any Thing in the Constitution or Laws of any State to the Contrary notwithstanding."

28 The preemption doctrine is imposed when state law or regulation "touch a field in which the federal interest is so dominant that the federal system [must] be assumed to preclude enforcement of state laws on the same subject." In the case of refusal to honor ICE detainers, state or local policies that ignore a federal directive are unconstitutional even though they purport to pursue or aid federal law. See Pennsylvania v. Nelson, 350 U.S. 497 (1956) and Charleston & Western Carolina R. Co. v. Varnville Furniture Co., 237 U.S. 597 (1915).

29 There is a reason for the existence federal Supremacy Clause, rooted in the history of our founding as a nation. The Articles of Confederation provided for only the loosest federal structure of government, preferring each colony/state to be co-equal and preeminent over that structure that did exist. In fact, the Articles did not refer to a nation, per se, but rather a "league" of states. The federal government possessed no chief executive — indeed, no executive branch whatever, nor a judiciary. Each state felt free to establish its own trading rules, its own laws governing citizenship, etc. Needless to say, the weakness of such a structure was its undoing.

30 The source of federal power to regulate immigration comes through a combination of international and constitutional legal principles. The Chinese Exclusion Cases (beginning with Chae Chan Ping v. United States, 130 U.S. 581 (1889)) were the first cases to hold that the federal authority to exclude non-citizens is an incident of national sovereignty. The Supreme Court reasoned that every national government has the inherent authority to protect the national public interest. Immigration, the court found, is a matter of vital national concern. The court distinguished between national and local spheres. It is the role of the federal government to oversee matters of national concern, while it is the province of the states to govern local matters. Therefore, the court found that the inherent sovereign power to regulate immigration clearly resides in the federal government. Subsequent cases reinforced national sovereignty as the source of federal power to control immigration and consistently reasserted the plenary and unqualified scope of this power. Fong Yue Ting v. United States, 149 U.S. 698 (1893) explicitly held that the power to expel or deport (now "remove") non-citizens rests upon the same ground as the exclusion power and is equally "absolute and unqualified".

31 Joseph Story, Commentaries on the Constitution of the United States, §1831. Stated Story: "The propriety of this clause [Supremacy Clause] would seem to result from the very nature of the Constitution. If it was to establish a national government, that government ought, to the extent of its powers and rights, to be supreme. It would be a perfect solecism to affirm, that a national government should exist with certain powers; and yet, that in the exercise of those powers it should not be supreme." See also The Founders' Constitution, Volume 4, Article 6, Clause 2, Document 42, Chicago: University of Chicago Press; and Joseph Story, Commentaries on the Constitution of the United States, 3 vols. Boston, 1833.

32 Comity is legal reciprocity, the principle that one jurisdiction will extend certain courtesies to other jurisdictions within the same nation, particularly by recognizing the validity and effect of their executive, legislative, and judicial acts. Part of the presumption of comity is that other jurisdictions will reciprocate the courtesy shown to them. In the United States, comity also refers to the Privileges and Immunities Clause (sometimes called the Comity Clause) in Article Four, Section 2, Clause 2 of the U.S. Constitution. The clause provides that "The Citizens of each State shall be entitled to all Privileges and Immunities of Citizens in the several States." See Legal Information Institute, Cornell University Law School.

33 Elizabeth Price Foley, "Presidents Cannot Ignore Laws as Written", The New York Times, January 29, 2014. Stated Professor Foley: "President Obama has shown a penchant for ignoring the plain language of our laws. He unilaterally rewrote the employer mandate and several other provisions of the Affordable Care Act, failing to faithfully execute a law which declares, unambiguously, that these provisions 'shall' apply beginning January 1, 2014. Similarly, in suspending deportation for a class of young people who entered this country illegally, the president defied the Immigration and Nationality Act, which states that any alien who is 'inadmissible at the time of entry' into the country 'shall' be removed."

34 Supreme Court, op. cit., p. 8

35 The Supreme Court has adjudicated disputes between federal and sub-federal entities in this arena for almost 150 years, siding overwhelmingly with the federal government and striking down state and local laws.

36 Jessica Vaughan, "ICE Document Details 36,000 Criminal Alien Releases in 2013", Center for Immigration Studies Backgrounder, May 2014.

37 See Chy Lung v. Freeman, 92 U.S. 275, 280 (1875) and Hines v. Davidowitz, 312 U.S. 52, 62 (1941). These cases hold "That the supremacy of the national power in the general field of foreign affairs, including power over immigration, naturalization, and deportation, is made clear by the Constitution was pointed out by authors of the Federalist in 1787, and has since been given continuous recognition by this Court."

38 The relevant statute can be found at Section 274(a)(1)(A)(iii) of the Immigration and Nationality Act (INA), codified at 8 U.S.C. 1324(a)(1)(A)(iii).

39 For one detailed explanation of judicial deference to administrative agencies, arising from a Supreme Court decision of 2004, see Randolph J. May, "Defining Deference Down: Independent Agencies and Chevron Deference", Administrative Law Review, Vol. 58, No. 2, Spring 2006 (58 Admin. L. Rev. 428 (2006)).

40 Carol D. Leonnig, "Probe: DHS watchdog cozy with officials, altered reports as he sought top job", The Washington Post, April 24, 2014.

41 Jessica Vaughan, "Catch and Release: Interior immigration enforcement in 2013", Center for Immigration Studies Backgrounder, March 2014.

42 Syracuse University, Transactional Records Access Clearinghouse, "Immigration Detainers Decline 39 Percent Since FY 2012: Current as of March 2014", November 12, 2014.

43 Thomas Zambito, "N.J. county jails setting free alleged criminals facing deportation, feds say", NJ.com, November 16, 2014, updated November 17, 2014.

44 See the cases of Erick Maya, of Cook County, Ill., who was recently sentenced to 122 years in prison for murdering his ex-girlfriend, and who was at large despite an immigration detainer, and Hector Ramires, of Chelsea, Mass., who is currently in custody on murder charges in an incident that occurred several months after arrests for armed robbery, in which ICE declined to issue detainers.

45 Center for Immigration Studies Fact Sheet, "Immigration Enforcement and Community Policing", September 2013.

46 Congressional Research Service, "Analysis of Data Regarding Certain Individuals Identified through Secure Communities", July 27, 2012.

47 Mark H. Metcalf, "Justice on the Run: Immigration court evasions reveal weak authority and weak enforcement", Center for Immigration Studies Backgrounder, April 2014.

48 Jessica Vaughan, op. cit., and Jessica Vaughan, "The Alternative to Immigration Detention: Fugitives", Center for Immigration Studies blog, October 18, 2011.

49 For more information on the issue of SCAAP funding, and the hypocrisy inherent in state and local agencies demanding reimbursement for incarceration costs of aliens they refuse to turn over to ICE, see Russ Doubleday and Jessica Vaughan, "Subsidizing Sanctuaries: The State Criminal Alien Assistance Program", Center for Immigration Studies Backgrounder, November 2010, and Jessica Vaughan, "After the Election, More Flexibility for Sanctuaries", Center for Immigration Studies blog, November 26, 2012.

50 INA Section 236(a), codified at 8 U.S.C. § 1226(a), states in relevant part, "On a warrant issued by the Attorney General, an alien may be arrested and detained pending a decision on whether the alien is to be removed from the United States."

51 For more on the EOPS memorandum and its flawed logic, see Dan Cadman's blog, "Mass. 'Public Safety' Office Seeks to Impede Immigration Enforcement", Center for Immigration Studies, September 16, 2014.

52 For an analysis of the SAFE Act, see W.D. Reasoner, "Better SAFE Than Sorry", Center for Immigration Studies, August 2013.