Download a PDF of this Backgrounder

Part 2: Foundations of a counter strategy

Part 3: Options for a counter strategy

Stanley Renshon is a professor of political science at the City University of New York and a certified psychoanalyst. He is also a Fellow at the Center for Immigration Studies.

Overview

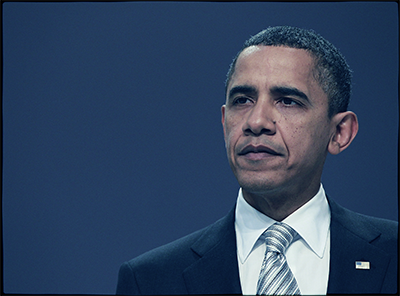

President Obama repeatedly promised to take sweeping executive actions to fix what he and his allies term America's "broken" immigration system before the end of the year. And on November 20, 2014, in an "Address to the Nation", he announced he was going to do so, and then did.

He said that his actions, preempting congressional legislative solutions, were necessary because of Republican opposition to "comprehensive" immigration reform embodied in the Democratic bill that passed the Senate in 2013, but which was not taken up by the House.

The executive decisions announced that day were implemented with two presidential memorandums to the heads of relevant executive agencies. They in turn triggered 10 separate Department of Homeland Security memos implementing the president's orders. The cumulative effect of these directives is to immediately shield up to five million illegal migrants from legal action and to provide them with legal working papers, thus allowing them access to certain government welfare benefits. These advantages are gained without any penalties or consequences. In that respect they are amnesties in every sense of the meaning of that word.

These memos are cumulatively unprecedented in their scope and sweeping in their impact. Not surprisingly, they have had a dramatic public impact, as was the president's intention. Their full political, legal, and legislative consequences however will not be clear for some time, but it will be substantial.

Almost all Republicans have been united in denouncing the president's executive actions. They see them as constitutionally suspect, contrary to the rule of law, politically provocative, and damaging to the enforcement foundation of American immigration laws. The president's Democratic allies in Congress have, almost unanimously, supported him. And his ethnic advocacy group allies have also supported his initiatives while complaining that he did not go far enough.

However, the real, and in many ways crucial, final arbiters of President Obama's unilateral actions are the American public. The president's immigration actions came at a time during which there has been a steep decline in public support for his overall leadership and a number of his domestic and foreign policies.

The American public could not help but notice the president's unilateral immigration actions and their response has generally been negative. In numerous polls, Republicans are, of course, more opposed to the president's actions, and Democrats more supportive. However, what is especially striking is that those who don't count themselves as partisans on the left or right do not support the president's unilateral actions, and Hispanics are equivocal about the process though they support the result.

The president, as expected, has framed his actions as necessary, legitimate, and even laudable. They are and will remain, however, extremely controversial. And it is that very controversy that provides both the basis and the vehicle for opposing these actions, and increases the likelihood that counter actions can be successful.

The question is how.

The analysis that follows proceeds in four separate parts. The first, "The President's Nullification of Immigration Law", outlines the key amnesty memos and analyzes their contributions to the nullification of immigration law enforcement. The second analysis, "The Foundations of a Counter Strategy" frames and analyzes the most important political elements of the bases on which to build an effective counter strategy. The third, "Options for a Counter Strategy", evaluates the specific legal, political, administrative, and legislative choices available to those opposed to the president's executive immigration actions. The fourth and final analytic paper will present a detailed alternative comprehensive immigration reform model for legislation, The American Immigration Reform Act of 2015, that can serve as the basis for finding common ground.

The President's Nullification of Immigration Law

- "And what we're saying essentially is, in that low-priority list, you won't be a priority for deportation. You're not going to be deported."1

- "This cannot stand. It will not stand."2

- "Obama's prospective order..: Even if its constitutional basis is weak, it's hard to see what anyone could do about it".3

- "63 percent [of Americans] Oppose Obama Executive Order On Immigration".4

On November 20, 2014 President Obama announced, in an "Address to the Nation,"5 that he was following through on his long-standing promise to undertake a series of unilateral executive actions governing the operation and enforcement of the American immigration legal system.6

The speech was followed the next day by the issuance of two Presidential Memorandums.7 One directed the creation of new "White House Task Force for New Americans."8 The other, far more consequential and controversial one, directed heads of all Executive Departments and Agencies to "within 120 days" make "recommendations to streamline and improve the legal immigration system — including immigrant and non-immigrant visa processing."9

The Administration's Immigration Directives

One day before the president's two directives, on November 20, 2014, Jeh Johnson, secretary of the Department of Homeland Security sent out a series of 10 memorandums. They are arranged below in tentative order from the most to the least constitutionally suspect and politically contentious.

The Memos Themselves

1. "Policies for the Apprehension, Detention and Removal of Undocumented Immigrants".10

2. "Personnel Reform for Immigration and Customs Enforcement Officers".11 "These policy changes should be accompanied by a recalibration of the ICE's ERO (Office of Enforcement and Removal Operations) workforce and personnel pay structure." In other words, ICE personnel working in the removal of illegal aliens would now be evaluated and reassigned to "priority missions", as outlined in Memo No. 1 above, and away from lower priority missions dealing with those who are not national security threats or convicted felons.

3. "Exercising Prosecutorial Discretion with Respect to Individuals Who Came to the United States as Children and with Respect to Certain Individuals Who Are the Parents of U.S. Citizens or Permanent Residents".12

4. "Secure Communities — The Secure Communities program, as we know it, will be discontinued".13

5. "Southern Border and Approaches Campaign" detailing a plan for "unity of effort" there.14

6. "Expansion of the Provisional Waiver Program", which would allow illegal aliens who might be eligible for a change of status to do so without leaving the country as has been the case in the past. That requirement would have, in the past, barred illegal aliens from returning to the country for either three or 10 years if they had formerly been in the country illegally for more than six months. Such persons could have in the past applied for a waiver because of "extreme hardship", but had to do so from abroad.15

7-9. Dealing with Revising Parole Rules for three different groups: 7) "Policies Supporting U.S. High- Skilled Businesses and Workers",16 8) "to issue new policies on the use of parole-in-place or deferred action for certain spouses, children, and parents of individuals seeking to enlist in the U.S. Armed Forces",17 and 9) "Directive to Provide Consistency Regarding Advance Parole".18

10. "Policies to Promote and Increase Access to U.S. Citizenship".19

The Extent and Scale of the President's Executive Immigration Actions. The number of illegal migrants who will be legalized under these directives is at this point unclear. The phrase that is frequently used is "up to five million",20 although other numbers, including four21 and 3.7 million22 been used. In truth, the actual final numbers will reflect (1) how many persons actually apply; (2) how many of those who apply are given legalization; and (3) how effective Congress and others opposed to the president's executive amnesty plans are in narrowing or reversing these initiatives.

President Obama has alluded to the fact that other presidents have acted administratively regarding illegal immigrants in the past. He claimed that "If you look, every president — Democrat and Republican — over decades has done the same thing, George H.W. Bush — about 40 percent of the undocumented persons, at the time, were provided a similar kind of relief as a consequence of executive action."23 That erroneous assertion received "Three Pinocchios" out of a possible four by the Washington Post fact checker.24

More directly to the point is a Washington Post editorial titled: "President Obama's unilateral action on immigration has no precedent."25 They are right. The president's unilateral executive amnesty initiative is wholly without precedent in either size or scope in American history, and no president has ever attempted such a sweeping immigration amnesty, acting by himself.26

The President's Direct Role

We now know that the White House initiated DHS Secretary Johnson's three-month review of immigration policy with an order "to use our legal authorities to the fullest extent" on a new deportations policy. The New York Times further reported that, "In five White House meetings over the summer, Mr. Johnson and Mr. Obama, both lawyers, pored over proposed changes, eventually concluding that the president had the authority to enact changes that could affect millions of people and significantly alter the way immigration laws are enforced."

Yet, when Secretary Johnson gave the president the results of his review of possible executive actions in May 2014, the president rejected them. Why? The secretary's first attempt "was rejected, White House officials said, because in the president's view, he did not go far enough. The effort only sought to sharpen the guidance for immigration agents, but did not provide work permits or directly shield anyone from deportation."27

That means that it is the president himself, and most likely several of his most senior advisors, who decided to push the limits of the executive amnesty well past what even his Secretary of Homeland Security was comfortable recommending. It further suggests that it was the president himself who personally made the choice about what to include, even when it went beyond what his secretary of Homeland Security originally recommended.

The president clearly wanted a large-scale monument to his boldness that would not only permeate America's politics for years to come, but would echo historically for his reputation as a "transforming" president.

Appreciating the Real Meaning of the Executive Amnesty Directives

Of the 10 administrative memos noted above, several are, at least in part, wholly unobjectionable, even anodyne. Promoting "unity of effort" among the various agencies responsible for helping to secure the Southern border (Memo No. 5) is a reasonable idea.28 Likewise, promoting citizenship (Memo No. 10) is the kind of presidential initiative that is likely to find support across the political spectrum. The idea of discounting citizenship test fees for those here legally and unable to pay, also contained in that same memo, is also something that most Americans, of whatever political affiliation, would likely support. Similarly, providing "parole for the families of those serving in the armed forces (Memo No. 8) is a change, but not, on balance, an objectionable one.

Unfortunately these are the exception, not the rule.

The other memos, in whole or in part, are inconsistent with effective immigration enforcement, and in many instances antithetical to it. And that is certainly their consequence, if not their purpose.

The first memo noted above, for example, is directed both to the commissioner of U.S. Customs and Border Protection, and the acting director of U.S. Immigration and Customs Enforcement. The importance of this may not be immediately obvious, but:

ICE is the U.S.'s lead deportation agency, but it is CBP that arrests and then turns over to ICE about half of the total aliens deported every year. And CBP itself carries out about another quarter of DHS's deportations. In addition, there are hundreds of thousands of "returns" every year —departures by noncitizens to avoid formal removal proceedings. ICE was subject to the old priorities, which DHS issued in 2011. CBP was not ... DHS Secretary Jeh Johnson for the first time instructed not just ICE but also CBP to consider the Department's priorities in deciding "whom to stop, question, and arrest," and "whom to detain or release." 29

In other words, the agencies that are on the front lines of immigration enforcement are now subject to the application of the new enforcement rules, with a corresponding increase in the number of illegal aliens removed from enforcement consideration.

Not incidentally, one part of Memo No. 2 that promises pay raises to ICE personnel demoralized by being unable to perform the enforcement roles that had been part of their core responsibilities until the Obama administration exempted more and more classes of people from being subject to it through the extension of "discretion".30 In so doing, the administration seems to be testing whether money, if it can't quite buy happiness when you are enjoined from doing the job you are committed to, can at least buy quiescence.31

The Provisional Waiver Program. Less cynical, but no less questionable, is Memo No. 6, which expands the provisional waiver program.32 Previously, American immigration law required illegal aliens who are spouses and children of U.S. citizens and who are "statutorily eligible for immigrant visas", to go abroad to apply for a change of status.

That requirement would have, in the past, barred them from returning to the country for either three or 10 years if they had formerly been in the country illegally for more than six months (barred for three years) or more than a year (barred for 10 years).

In the past, such persons could have applied for a waiver because of "extreme hardship", but had to do so from abroad. In 2013, the rules were changed to allow such a person to get a "provisional waiver" before they left the country, but they still had to leave the country to finish their application.

The new directive expands the provisional waiver program to all eligible classes of relatives, and directs that the concept of "extreme hardship" be administratively defined, so that it provides "broader use".33

Secretary Johnson estimates in his memo that, "To date, approximately 60,000 individuals have applied for the provisional waiver, a number that, as I understand, is less than was expected." Extending the classes of person to whom the provisional waiver can apply, and expanding the definition of "extreme hardship" to cover the numerous new factors, he says, should be considered to have a clear purpose. The secretary's intent is clearly to expand the number of illegal migrants to whom the waiver rule applies.

The importance of this memo is not in the large numbers that will now benefit without incurring any penalty for having violated American immigration law. Those numbers are likely to be comparatively small given a figure of roughly a million new legal immigrants every year, a population of illegal immigrants that numbers between 11 and 12 million, and the president's executive actions that will provide legalization for up to five million illegal aliens.

What this provisional waver memo does do is to provide a route to legal status including citizenship for this group of illegal aliens. This allows the formerly illegal migrants to apply for government welfare benefits and to sponsor their families for eventual legal status — all without incurring any penalties whatsoever for violating immigration laws.

In the past, persons living here illegally who would have to leave the country and apply from outside would trigger the penalty of the 3/10 year bar for their past immigration offenses. However, with the new waiver they can do so with the legal expectation that they would be allowed to adjust their status to that of Legal Permanent Resident (LPR). That is the legal status that leads to citizenship.

So when the president says of his executive actions, "So this isn't amnesty, or legalization, or even a path to citizenship," he is either uninformed or being untruthful.34

The Immigration Enforcement Nullification Memos

The provisional waiver memo is also important for what it reveals about the mindset, purpose, and ultimate consequences of the president's actions. It reflects an effort, through expanding categories of people covered by it, and by expanding the definition and the grounds on which they can make use of it,35 to increase the number of illegal migrants who are not subject to any enforcement penalties for having violated American immigration law.

This mindset is very evident in the three major departures from constitutional frameworks and long-settled political practice that we will examine herein: (Memos Nos. 1 and 2) having to do with enforcement priorities; the portion of Memo No. 3 that creates a new DACA-like program on "a case by case basis" for all illegal adults "who have a son or daughter who is a U.S. Citizen or lawful permanent resident";36 and, finally, Memo No. 4, which cancels the Secure Communities Program.

One of the two primary core elements of the administration's attempt to nullify immigration enforcement is contained in the memo entitled, "Policies for the Apprehension, Detention and Removal of Undocumented Immigrants".37 This memo lays out three priorities in decreasing order of importance.

The basic, and repeated rationale for setting these new priorities is what might be called the "limited resources" argument. This argument is based on the fact that the agencies responsible for carrying out American immigration policy (The U.S. Immigration and Customs Enforcement; U.S. Customs and Border Protection; U.S. Citizenship and Immigration Services; and the Department of Homeland Security more generally) operate on a budget.

The administration's claim is that with limited budgets they must make choices.38 Hence the priorities set out in the Apprehension/Removal memo. They are:

Priority 1: National security threats, convicted felons, gang members, and illegal entrants apprehended at the border.

Priority 2: Those convicted of significant or multiple misdemeanors and those who are not apprehended at the border, but who entered or reentered this country unlawfully after January 1, 2014.

Priority 3: Those who are non-criminals, but who have failed to abide by a final order of removal issued on or after January 1, 2014.39

Understanding the Administration's Limited Resources Argument

The first two memos examined here present a rationale for the president's executive amnesty that the administration hopes will be seen as a legitimate and "common sense" response to the limits they say are imposed by insufficient congressional funding. Their basic rationale for the expansion of "discretion" past any previous boundaries and the executive amnesty is the limited resources argument.

They claim that Congress has just not appropriated enough money for them to deport more than 400,000 illegal migrants a year. That being the case, it makes sense, they argue, to set priorities, or as the memorandum puts it, "in the exercise of that discretion, DHS can and should develop smart enforcement priorities, and ensure that use of its limited resources is devoted to the pursuit of those priorities." Or, as the president recently put it, "Congress only allocates a certain amount of money to the immigration system, so we have to prioritize."40

On its face, the setting of priorities given limited resources makes sense. It would be hard to argue, especially after 9/11, that no resources should be devoted to deterring or stopping national security threats. On the other hand, the framing of this argument by key administration officials is misleading, at best.

Consider the testimony of León Rodriguez, a former Justice Department lawyer and the newly confirmed director for U.S. Citizenship and Immigration Services. In testimony before the House Committee on the Judiciary in July, Mr. Rodriguez told lawmakers that the government doesn't have the resources to deport the more than 11 million immigrants estimated to be living illegally in the United States, "so, the question is, are we going to let them persist in the shadow economy or are we going to have them work and pay taxes?"41

Of course, the choice is not between deporting 11 million illegal aliens and legalizing them. There are many policy options in between these two extreme poles and Mr. Rodriguez knows that, or should.

And, no matter how many illegal aliens might be legalized, on what grounds, and with what penalties — questions Mr. Rodriguez doesn't address in his testimony,42 there is another critically important question, often unasked and never answered: How can the United States keep from having millions of new illegal migrants in the future? How can the same problem be kept from happening again?

How Much Enforcement is Not Enough or Too Much?

A second set of issues is that it is totally unclear is how numerous each priority's threats are, how much in the way of enforcement resources they require, and how much help DHS gets from others agencies (FBI, CIA, state governments) for Priority 1 and other enforcement categories. How much of the agency's resources are devoted to each priority level? Is that number 2 percent, 5 percent, 25 percent, or more of the enforcement budget?

Some sense of the relative effort made can be gleaned from a 2009 memo that instructed that agents working in the National Fugitive Operations Program:43

[S]hould focus their resources. Teams must focus the vast majority of resources, at least 70%, on tier I fugitives. The remainder should be directed to tiers 2 and 3.

It would be instructive to find out specifically just how much of the agency budgets charged with immigration enforcement are taken up with the three levels of stated priorities outlined in Secretary Johnson's November 20 memos and, as well, the allocation of resources with those categories. That is one of the many questions that could be asked in congressional oversight hearings.

Whatever those actual numbers might prove to be, one thing is very clear: A focus on the highest priority, followed by a focus on the second highest priority, coupled with limited resources, means that those in the third priority categories have little, if any, reason to fear being caught up in any form of immigration enforcement. And indeed that is factually the case.

Well before the president's executive actions, John Sandweg, who until last year was the acting director of Immigration and Customs Enforcement, said in an interview that, "If you are a run-of-the-mill immigrant here illegally, your odds of getting deported are close to zero — it's just highly unlikely to happen."44 His candid observation is reinforced by recent reports that deportations have dropped.

According to the Los Angeles Times story that reported the data:

Immigration agents removed 315,943 people in the year that ended Sept. 30, a 14 percent drop and the lowest total since President Obama took office. ... About two-thirds were sent back to their home countries after being caught at the border. Those removals were down 9 percent from 2013. ... An even bigger decline came in the numbers of people removed after living for some time in the U.S., mostly after being ensnared in the criminal justice system. About 102,000 people were sent out of the U.S. in these so-called interior removals — a 23 percent drop from 2013, and fewer than half the number of people deported in 2011.45

Along similar lines, a recent New York Times story reported:

New deportation cases brought by the Obama administration in the nation's immigration courts have been declining steadily since 2009. ... The figures show that the administration opened 26 percent fewer deportation cases in the courts last year than in 2009. ... The steepest drop in deportations filed in the courts came after 2011, when the administration began to apply more aggressively a policy of prosecutorial discretion.46

The reason for this is no mystery. In a series of memos dating back to the very first years of the Obama presidency in 2009, then Associate Director of U.S. Immigration and Customs Enforcement, John Morton (later promoted to director) issued a series of directives, all based on the resource scarcity argument, that have essentially suspended immigration enforcement for millions of illegal aliens.47

Advocates of comprehensive immigration legislation from both political parties have repeated the essentially meaningless mantra "the system is broken" so often that it passes for conventional knowledge.48 No one repeating this refrain bothers to specify what, exactly, is broken. The United States, for example, takes in roughly a million new legal immigrants per year and has for many years and that part of the system seems to be working quite well.

If anything is "broken" in American's immigration system, is it immigration enforcement.

Understanding the Administration's Discretion Argument

Administrative discretion is built into administrative structures for a very simple reason: It is needed. No set of rules can cover every circumstance. And no set of circumstances is exactly alike.

The administrative rules, then, are derived from the basic stance of the laws that underlie them, and these in turn reflect the governing legal, moral, and political stance that led to their development and enactment. In immigration law, the basic stance is quite clear. The law is meant to lay out an orderly process of legal immigration and, equally important, to also set out the consequences for not following those rules. More directly, the consequence of following the rules is the granting of legal status; the consequence of not following the rules is no legal standing to enter or stay in the country, and certainly not to work.

It is true that presidents have made small adjustments in this basic legalization-enforcement framework over the years in response to specific circumstances.49 These, however, have been small exceptions to the general rule, taken in consultation with and the agreement of Congress. In these kinds of cases, the circumspect application of exceptions fortifies the basic rule by carefully specifying and limiting the circumstances in which it can be used.

The Problem with Discretion: When the Exception Becomes the Rule

Nothing that can remotely be described as circumscribed can be used to characterize the Obama administration's approach to American immigration law. Mandates to exercise "discretion" permeate the new administration rules. Administrative discretion is not only built into the setting of priorities, but in the unfolding of the apprehension/removal process from start to finish, and that entails many steps. So,

In the immigration context, prosecutorial discretion should apply not only to the decision to issue, serve, file, or cancel a Notice to Appear, but also to a broad range of other discretionary enforcement decisions, including deciding: whom to stop, question, and arrest; whom to detain or release; whether to settle, dismiss, appeal, or join in a motion on a case; and whether to grant deferred action, parole, or a stay of removal instead of pursuing removal in a case.50

Notice that no rules are enunciated for any of these interventions; they are simply blanket opportunities to exercise "discretion". Discretion, as noted, is ubiquitous in administrative life, but its rationale and legitimacy are ultimately to be found in the fair-minded application of congressional intent. Congress's core intent is spelled out in 8 U.S.C. § 1227 on "Deportable aliens", which reads in part: "Any alien who is present in the United States in violation of this chapter or any other law of the United States ... is deportable."51

The new rules set up a three-tiered priority system that will determine what resources will be used, how agents will enforce the law, and against whom. Priority 1 consists of the most serious immigration violators — persons engaged in terrorism, espionage, or organized criminal activity; who have been convicted of a felony or an aggregated felony; and, somewhat oddly given the nature of the other members of this category, those "aliens apprehended at the border or ports of entry while attempting to unlawfully enter the United States."

With the exception of the last entry in this Priority 1 membership group, all these are very serious criminal offenders. However, the memo then states that,

"The removal of these aliens must be prioritized ... unless, in the judgment of an ICE Field Office Director, CBP Sector Chief, or CBP Director of Field Operations, there are compelling and exceptional factors that clearly indicate the alien is not a threat to national security, border security, or public safety and should not therefore be an enforcement priority."52

So these dangerous felons and national security risks "must be prioritized", except when they shouldn't because of "compelling and exceptional factors". What are these? The memo leaves that up to those exercising the discretion.

Priority 2 offenders have committed less serious crimes, generally several or "significant" misdemeanors. Here again, the memo contains exceptions. It, too, provides a list of ICE personnel that can countermand the enforcement priorities within these categories, but there is something else as well. Priority 2 contains two classes of persons who are not convicted criminals: those who have overstayed their visas and "aliens apprehended anywhere in the United States after unlawfully entering or re-entering the United States".

Very oddly, these two categories of Priority 2 offenders receive additional layers of administrative discretion. Visa violators are a Priority 2 except "aliens who, in the judgment of an ICE Field Office Director, USCIS District Director, or USCIS Service Center Director, have significantly abused the visa or visa waiver programs."

There is no indication what "significantly abused" means. However, it does suggest that simply overstaying the period of stay you were given upon entry is not enough to trigger enforcement actions.

Indeed, this appears to be a formal codification of what other legal scholars have already pointed out, that in the old pre-2014 priority system,

What mattered was whom the list didn't mention: people who had overstayed their visas, along with people who came to this country years ago and had never received a deportation order. Since 2011, ICE has mostly declined to remove people in these "non-priority" categories.53

And then there is, finally, this class of persons specified as Priority 2 targets for enforcement: "aliens apprehended anywhere in the United States after unlawfully entering or re-entering the United States". However this category of Priority 2 enforcement contains the following administrative discretion disclaimer: "and who cannot establish to the satisfaction of an immigration officer that they have been physically present in the United States continuously since January 1, 2014."

A straightforward reading of that exception suggests that a person detained after unlawfully entering or reentering and who can establish to the satisfaction of an immigration officer that they have been physically present in the United States continuously since January 1, 2014, will cease to be a Priority 2 enforcement case. Exactly why is unclear.

In fact, the lower down on the administration's priority list you go the larger the absolute numbers in the group. The most resources are presumably put toward the categories that have the fewest numbers of people in them. 54 So, for example, those "aliens convicted of an offense for which an element was active participation in a criminal street gang" are in the Priority 1 category. However, their numbers are dwarfed by the hundreds of thousands of persons in the lowest, Priority 3, category and the millions more illegal immigrants not in any priority at all. This means that most illegal immigrants have little to fear about being caught and made to leave the country.

Trust, Discretion, and the Administration's Good Faith Problem

The problem with discretion is not its existence, but its good-faith application. The mindset of the Obama administration and its senior immigration officials has, from the period of their transition into office, focused on narrowing and scaling back ordinary immigration enforcement against those who haven't committed espionage, engaged in terrorism, or been convicted of serious felonies.

Even before Mr. Obama officially stepped into office, the work of his transition team in the area of immigration made the administration's outlook clear. The administration transition team set up a number of working groups to provide policy ideas for the new administration, immigration among them.55 These groups in turn developed position papers or blueprints to aid policy development once the president was in office.

One of these, "Immigration Policy: Transition Blueprint for the Obama Administration, 2008",56 gives a flavor of advice the administration received. The document does not use the word "illegal", but it states that workplace raids "threaten the identity of our country" and "hard working families are being torn apart for the crime of trying to put food on the table." Among its recommendations: repeal the expedited removal policy (pp. 9-10); create "a path to citizenship for the millions of undocumented immigrants throughout the country" (p.25); require a yearly civil-rights and civil liberties audit of E-Verify practices (p.11); and so on. And in keeping with the perspective outlined in the blueprint, the contributors are confined to a long list of leftist "rights" and "justice" groups.57

The administration has also not been honest in its public explanations or transparent in its use of immigration data. The president has both touted and then regretted his designation as "deporter-in-chief".58 At first, the administration's deportation statistics made the president look like a real enforcement hawk, a public stance he allowed so that he would have the public credibility needed to pass a sweeping Democratic immigration bill. When that effort stalled, his Hispanic advocacy allies grew impatient and used the term against him. The president was not pleased,59 but like so many other problems that have arisen in his administration it was his own fault.

The president had tried to get public credit for his strong enforcement credentials, but he did so by manipulating data categories and counting as "removals" people who would in the past have been counted as "returns". There is an important distinction between illegal immigrants who are caught and "returned", i.e., simply sent back without processing or penalty, and "removed", i.e., processed with the penalty of establishing a record that would make their attempted reentry a felony.60 The more commonly used word "deportation" refers in most people's mind to a process wherein someone goes before a legal adjudication and is ordered out of the country. When used with that understanding, "deportation" is much closer to the formal definition of "removal" than "return".61

The president and his administration deliberately blurred the two categories, without informing the public of the distinction.62 In that way, the president was able to get undeserved credit for appearing to be tough on immigration enforcement, at the same time that his Director of U.S. Immigration and Customs Enforcement, John Morton, was implementing a series of "discretion" memos that considerably and continuously narrowed the basis for ordinary immigration enforcement. The scheme began to unravel when the Republican House failed to pass the Senate Democratic immigration bill, and real numbers regarding deportation started to become more widely public.63

Discretion Redux: The Administration's Record on Criminal Enforcement

The stock response to those who criticize the administration for its failure to enforce immigration law is "first things first". The administration would counter that we have to go after those who are the most dangerous or more egregious violators of our immigration system. It would, however, be a far more reasonable argument if the administration actually had a good track record in successfully prosecuting its priorities. It doesn't.

A 2014 draft report by ICE said that, "To both comply with current detention-focused laws and court decisions and ensure available detention space for border enforcement activity and national security/public safety efforts, ICE also released 129,921 aliens from custody, 30,862 of whom were convicted criminals."64 In 2013, ICE released over 36,000 convicted criminals awaiting the outcome of their deportation hearings, including those convicted of homicide, sexual assault, kidnapping, aggregated assault, stolen vehicle, drunk or drugged driving, and flight to escape convictions.65 That is just the number of those convicted criminals in deportation hearings. The number of criminal aliens convicted of deportable offenses, but still released, is almost double that number.66

Immigration enforcement has been substantially unable to deal with the very large and growing problem of "fugitive aliens" (absconders). This is a person who, "failed to leave the United States after he or she receives a final order of removal, deportation or exclusion, or who has failed to report to ICE after receiving notice to do so."67

How do we know that the problem is bad and getting worse? The Office of the Inspector General of the Department of Homeland Security tells us so:68

Despite the efforts of the teams, the backlog of fugitive alien cases has increased each fiscal year since the program was established in February 2002. The fugitive alien population is growing at a rate that exceeds the teams' ability to apprehend.

...

The backlog of fugitive alien cases has increased, on average, 51,228 each year over the four-year period ending September 2005. Also, the increase for the period from October 2005 to August 2006 was 86,648 fugitive alien cases.

In other words, the backlog of fugitive alien cases has increased each year by a substantial amount, and the percentage of yearly increase shows signs of rapid growth. In the words of one major newspaper report, "Sharp Increase Is Seen in Deportation Evasion".69

The substantial growth in the fugitive alien population can also be seen in the Inspector General's estimates. The September 2001 estimate was 331,734. A year later the estimate was 376,003. In September 2005, that figure had passed the half a million mark (536,644), and by August 2006, it had reached 623,293.

What are those figures now? The number of fugitives is believed to have fallen toward the end of the Bush administration due to enhanced enforcement efforts, but has risen again under the current administration. DHS has not provided new estimates of the number of fugitives, but it did report that in 2013 there were 872,504 people with final orders of removal who had not yet departed.70 The overwhelming majority of these are fugitives, though a small share are people whose home countries will not accept them back.

Fugitive tracking, capture, and removal is costly, time consuming, and difficult. And regardless of the varying metrics that have been used to measure success, it is clear that tracking those who disappear is much more difficult that keeping them from doing so or keeping them out of the country or able to gain employment (see Part 4).

The Unraveling of State, Local, and Federal Immigration Enforcement Partnerships

It has been clear for some time that, "Enforcing immigration laws is a daunting task, and further, "that it is utterly unrealistic to expect that the immigration problem can be solved by federal law enforcement alone."71 And as a 2010 Rand report notes,

One possible response to this dilemma would be to encourage the creation of partnerships among federal immigration agencies and state and local law enforcement agencies so that their combined expertise, manpower, and other resources could be directed to apprehending and deporting fugitive aliens.

The Rand report examines the history of federal, state, and local efforts to cooperate with immigration enforcement beginning with 287(g).72 That cooperation allowed immigration enforcement officials to check the records of those arrested locally for crimes to see if they were also wanted for breaking immigration laws, and if so, to hold them for immigration authorities.

Effective Federal-State-Local Partnerships: Equivocal Responses

The Rand report notes that the response in a number of cities and states to these efforts has been equivocal. In some cases localities,

[A]dopt a policy of limited cooperation — e.g., to support federal efforts to remove illegal immigrants convicted of felonies, but otherwise to decline to identify and remove undocumented aliens, on the basis that this is a federal function. ... As of December 2008, states and municipalities have passed 87 laws, resolutions, and policies providing some degree of "sanctuary," which range from local government agents refusing to cooperate in the enforcement of immigration offenses to the equivalent of a "don't ask, don't tell" rule for immigration status. Indeed, four states — Alaska, Montana, New Mexico, and Oregon — explicitly prohibit the use of state resources for the purpose of immigration enforcement. Moreover, some of the largest cities in the United States — including New York, Los Angeles, San Francisco, the District of Columbia, Chicago, Baltimore, Boston, Detroit, Minneapolis, St. Louis, Newark, Philadelphia, Austin, and Seattle — have passed legislation limiting local enforcement of immigration laws. (p.3).

Not coincidently, these localities and cities have large numbers of immigrants, both legal and illegal, and they also have a large number of Democratic voters and a large number of Democratic politicians. Legal members of the immigrant community join forces with advocates and politicians to insist on a policy of enforcement neglect, and the result is codified into law and policy.73

And their efforts have been successful.74 In their 2014 "Removal Operation Report", ICE noted that there are an "increasing number of state and local jurisdictions that are declining to honor ICE detainers. As a result, instead of state and local jails transferring criminal aliens in their custody to ICE for removal, such aliens were released by state and local authorities. Since January 2014, state and local law enforcement authorities declined to honor 10,182 detainers."75

Communities that refuse to cooperate with ICE say it is in response to the conflict between enforcing the law as it stands and providing protection to all members of a community, whatever their legal status. Illegal aliens are understandably concerned about coming into contact with the police and risking deportation. That fear is said to make them more vulnerable to crime and less available to help police in their communities. Sanctuary policies focus on the latter at the expense of the former, although it is possible to implement a program like 287(g) taking into account the concerns of the community that might be affected by it, explaining its nature and limits, and reassuring the community.76

The insistence on non-cooperation and non-enforcement has been the primary response in localities in which federal, state, and local enforcement partnerships are most needed. More damaging is the fact that this perspective has become the dominant approach of the Obama administration's federal-state-local immigration enforcement cooperation.

The Obama Administration's Response

No federal policy program is without flaws and the 287(g) partnerships were no exception.77 The DHS inspector general issued a report on the program that contained a number of recommendations. That was followed two years later with another, updated report from the inspector general stating that,

Since our initial 287(g) report in March 2010, ICE has made significant progress in implementing our recommendations. To close a recommendation, we must agree with the actions ICE has taken to resolve our concerns. Of the 62 total recommendations included in our prior reports, 60 have been closed based on corrective action plans and supporting documentation provided by ICE.78

The 287(g) program was substantially effective in identifying local lawbreakers with outstanding immigration violations,79 for some too much so. Liberal advocacy groups complained about "continuing abuses",80 and made the mistaken claim that the program "was originally intended to target and remove undocumented immigrants convicted of violent crimes, human smuggling, gang/organized crime activity, sexual-related offenses, narcotics smuggling, and money laundering."81

In the middle of efforts to further address the inspector general's reform suggestions, the Obama administration reduced the program's budget allocation by $17 million.82 Nine months later, ICE at the very end of a pre-Christmas news release quietly announced,

In addition, ICE has also decided not to renew any of its agreements with state and local law enforcement agencies that operate task forces under the 287(g) program. ICE has concluded that other enforcement programs, including Secure Communities, are a more efficient use of resources for focusing on priority cases.83

Ironically, the rationale for reducing the budget of the 287(g) program and then abolishing major parts of it, contained in DHS's 2013 budget was as follows:

This request reduces the 287(g) program as Secure Communities reaches nationwide deployment in FY 2013. The Secure Communities screening process is more cost effective in identifying and removing criminal aliens and other priority aliens than the officer-focused 287(g) model. 84

The irony is that the Secure Communities program, touted by DHS as a rationale for narrowing the 287(g) program, has now itself been canceled. One of the president's 10 executive amnesty memos from his DHS secretary states the case directly: "I am directing U.S. Immigration and Customs Enforcement (ICE) to discontinue Secure Communities."85

Beyond the irony, the reasons that Secretary Johnson gives for discontinuing the 287(g)'s successor program are instructive:

[T]he reality is the program has attracted a great deal of criticism, is widely misunderstood, and is embroiled in litigation; its very name has become a symbol for general hostility toward the enforcement of our immigration laws. Governors, mayors, and state and local law enforcement officials around the country have increasingly refused to cooperate with the program, and many have issued executive orders or signed laws prohibiting such cooperation. A number of federal courts have rejected the authority of state and local law enforcement agencies to detain immigrants pursuant to federal detainers issued under the current Secure Communities program.86

The coordinated complaints, real and exaggerated, amplified by immigration activists and their Democratic supporters in state and local government, aided in part by a relatively small number of limited court concerns, have found a willing and powerful ally in the Obama administration.

And, as a result, the country now has no functioning program to help coordinate and build partnerships for immigration enforcement at the local, state, and national levels.

The Johnson memo announces yet another new successor program, the "Priority Enforcement Program" or "PEP", to take the place of the two other programs.87 Importantly, under the new program, local and state law enforcement officials, "will only notify ICE agents that someone with an immigration violation has been arrested. The ICE official will not respond if the person does not fit into one of the priority groups."88 (Emphasis added.) Since there are limits to the length of time that such persons can be held, a non-response will mean that person is simply released.89

However, the basic and as yet unresolved dilemma regarding these programs is very clear. To the extent that any federal, state, and local partnership program effectively identifies and helps remove any but the most serious criminal aliens, it will be attacked and ultimately abandoned. To the extent that it allows the many millions of illegal aliens now present to stay and work in this country without fear of removal it will be supported.

As such, this element of the president's executive amnesty provisions is entirely consistent with his general effort to nullify the country's basic immigration enforcement laws and policies.

President Obama's Hidden Amnesty

The new immigration enforcement priorities, as evidenced in the new executive amnesty memos, concentrate on terrorists, convicted felons (Priority 1), and repeated misdemeanants and new illegal aliens (Priority 2). As a result, almost all other illegal aliens who constitute the vast majority of the country's 11-12 million illegal alien population may now live and work in the country without fear of consequence.

It is important to be clear about what this means. While the president's executive amnesty will officially cover an estimated four to five million illegal aliens who have children who are American citizens or legal permanent residents and have been in the country since before 2010, the actual number of illegal aliens receiving some form of administrative amnesty (though not work permits) will be substantially higher.90

The administrative discretion memos essentially stop the enforcement of immigration law for all those illegal aliens who are not terrorists or convicted major felons, whether they have children who are citizens or LPRs or not.

The President's Executive Amnesty Real Numbers

The reason is that there are really three classes of illegal aliens involved in the president's executive amnesty memos: (1) terrorists, convicted felons, and multiple convicted "misdemeanants", (Priorities 1 and 2); (2) those directly covered by the presidential amnesty provisions; and (3) those not covered by the amnesty provisions, but essentially not subject to enforcement. Note that even the "convicted felon" category contains a loophole. The recently released ICE report on 2014 enforcement operations notes, deep in the analysis that ICE focused interior operations on criminal convictions, emphasizing those convicted of the most serious crimes.91

While news reports and commentary have focused on the number eligible for administrative amnesty and work papers, the real numbers are substantially higher.

The administrative amnesty memos set up three distinct groups: (1) those covered by the three priority categories, with their many discretionary caveats; (2) those benefitting from the work-permits amnesties (DAPA & DACA); and (3) all other illegal aliens, who are not in the priority lists at all. This last group is an enormous number.

As a result, the total number of illegal aliens being given direct and de facto amnesty is likely to be quite a bit higher than the estimated five million figures that have been associated with estimates of parents of American citizens and legal permanent residents. How much higher? Nine to 10 million would not be an outlandish estimate.

Seen from this perspective, the president's executive amnesty memos essentially provide de facto legalization to almost the entire illegal immigrant population, minus terrorists, convicted felons, and multiple misdemeanants.

Additionally, the executive amnesty memos allow a large class of illegal aliens to change their status to Legal Permanent Resident (LPR) without suffering the consequences of previous immigration offenses, effectively repealing the 3/10-year bar. This will be accomplished by granting "provisional waivers" to those who, under previous requirements, had to leave the country and reapply to come back in again, before they leave.

The administration has also expanded the number of persons who are eligible for this special consideration. Before 2013, all persons (legal or illegal) seeking to adjust their status to that of LPR had to leave the country and apply at a consular office abroad to return, thus tripping the 3/10-year bar if they were illegal aliens. Waivers of the 3/10-year bar were available, but they also had to be applied for abroad, meaning that those who were rejected had already removed themselves from the United States. In 2013, DHS allowed provisional waivers — that is waivers granted before leaving the country — but only for the "spouses and children of U.S. citizens."92 That pre-travel waiver has now been expanded to include the "the spouses and children of lawful permanent residents and the adult children of U.S. citizens and lawful permanent residents."

The memo also directs that DHS provide "guidance" for the determination of "extreme hardship" that would trigger such a "provisional waiver". There follows a robust list of the factors that the secretary feels should be taken into account. They include but are not limited to:

[F]amily ties to the United States and the country of removal, conditions in the country of removal, the age of the U.S. citizen or permanent resident spouse or parent, the length of residence in the United States, relevant medical and mental health conditions, financial hardships, and educational hardships.

The secretary further requires "USCIS to consider criteria by which a presumption of extreme hardship may be determined to exist" — not evidence, mind you, but presumption.

Hidden in Plain Sight: The President's Real Executive Amnesty

Public and press interest before the president's executive amnesty memos were issued focused on who and how many would be covered. Anticipation and speculation raged. Would the president "go big"?93 Which group/s would be covered? Would the parents of U.S. citizens and legal permanent residents be included? Yes, they would. Would the parents of dreamers, those who brought their young children here illegally be included? No, they wouldn't.94

Why one group and not the other? Marketa Lindt, a partner at Sidley Austin who serves as national secretary of the American Immigration Lawyers Association, said in an interview, "If the executive branch has the authority to give work benefits to people who arrive at a certain age, there's no different legal foundation to giving the benefits to the parents of those people." She suggested that rewarding parents who brought their children here illegally would be "a category that's hard to sell politically."95

The administration knew the numbers they could officially put before the public would count. The Washington Post reports of the administration that, "while they did not start with a specific number of people who would be eligible for deferrals, they also worked to ensure that the program didn't encompass numbers that it would look as if the president was defying Congress outright."96

The Department of Justice legal justification memo for the president's executive amnesty is well aware of this issue and specifically makes the point that, "while the potential size of the program is large, it is nevertheless only a fraction of the approximately 11 million undocumented aliens who remain."97

That statement was absolutely misleading, and knowingly so. Those responsible for gathering and assessing immigration statistics were obviously well aware of the real enforcement numbers and the impact of the new executive amnesty memos on them.

As expected, most news reporting focused on the specific group that was covered and how many persons would be eligible. Estimates were given,98 and since no reliable hard actual numbers were possible to find, the story narrative quickly turned to the Republican response and their strategies and chances to overturn the president's actions.99

Missed in the rush was a major story of an unprecedented scale and implication: The president had through his executive actions virtually provided an administrative amnesty to almost every illegal migrant now living and working in the United States.

That phrasing is not a mistake. It is not hyperbole. It is not hyper-partisan spin, or even basic spin. If you carefully read the executive amnesty memos and what they actually say about immigration enforcement, it is no more and no less than an accurate statement of what is contained in them.

To repeat: An illegal alien who is not a terrorist or a convicted felon or a multiple misdemeanant need not worry about immigration enforcement or deportation.

With his executive order memos, the president has essentially nullified immigration law by suspending its enforcement.

Which groups no longer have anything to fear regarding immigration enforcement?

Amnesty Group 1: Up to five million illegal migrants who have children who are American citizens or Legal Permanent Residents.

Amnesty Group 2: Close to half the total estimated 11.7 million illegal migrants residing in the United States as of 2013100 who overstayed their visas.101 That would be somewhere around 5.85 million estimated visa overstays eligible for legalization.

We know that there are substantial differences in the nature and size of the population between groups 1 and 2 because the Pew Center reports that, "Unauthorized immigrants from Mexico account for two-thirds of those who will be eligible for deportation relief under President Obama's executive action, even as they account for about half of the nation's unauthorized population."102

While there is certain to be some overlap, most of those in Group 1 came into the United States by crossing over somewhere on the country's southern border. They did not overstay their legal visas.

Amnesty Group 3: Illegal migrants who have reentered the country and would be subject to the 3/10 year bar if they wanted to change their status, and wish to do so.

Amnesty Group 4: According to testimony of Secretary Johnson, "the lowest priority are those who are non-criminals, but who have failed to abide by a final order of removal issued on or after January 1, 2014."103

Notice the dates, "on or after January 1, 2014." That means that any non-high-priority convicted felon who is apprehended from that date going forward, and who has been issued a final order of removal, will still be able to remain in the country without fear of deportation because they are in the lowest priority category.

According to the memo, the Priority 3 group "should generally be removed unless they qualify for asylum or another form of relief under our laws or, unless, in the judgment of an immigration officer, the alien is not a threat to the integrity of the immigration system or there are factors suggesting the alien should not be an enforcement priority."104 (Emphasis added.)

Amnesty Group 5: Persons caught trying to illegally enter the country at the border are the highest priority "unless they qualify for asylum or another form of relief under our laws, or unless, in the judgment of an ICE Field Office Director, CBP Sector Chief, or CBP Director of Field Operations, there are compelling and exceptional factors that clearly indicate the alien is not a threat to national security, border security, or public safety and should not therefore be an enforcement priority."105

So persons caught trying to enter the United States "at the borders" are a top priority, but what of those who make it past the border into the country? Those persons who are caught "after unlawfully entering or re-entering" the country are a second level priority, but only if they "cannot establish to the satisfaction of an immigration officer that they have been physically present in the United States continuously since January 1, 2014."106 Otherwise they are not a priority and need not worry about immigration enforcement or removal.

It is easy to miss the enormity of what is being said in the memo. If an illegal migrant was in the country before January 1, 2014, and that person is not a priority at any level, then for all intents and purposes he is just left alone to continue to live and work in the United States. Notice, too, that this applies to those who are caught after illegally "re-entering" the country; that is, they are at least second offenders (and felons, because re-entry after deportation is a felony), yet they are not a priority at any level and therefore will left alone.

Speaking at an Immigration Town Hall in Nashville, Tenn., the president said this:

We're going to set up priorities in terms of who is subject to deportation. And at the top are criminals, people who pose a threat, and at the bottom are ordinary people who are otherwise law abiding. And what we're saying essentially is, in that low-priority list, you won't be a priority for deportation. You're not going to be deported.107

That was no misstatement, but a fact.

Amnesty Group 6: De facto amnesty for other illegal aliens who are not in the priorities lists at all, and because of that can live and work in the United States without fear of legal action. This, as noted, is an enormous number.

Conclusion

The consequences of the president's executive actions are nullification of the country's basic immigration enforcement laws.

The major executive amnesty memos analyzed above represent an unprecedented change in our immigration laws, all done by the president acting unilaterally.

When the president says, speaking of his actions, that "we've changed our enforcement priorities in a formal way,"108 he is exactly right. When he said in response to a heckler's complaint, "I just took action to change the law"109 he was absolutely serious, and absolutely correct. And in doing so he has gone well beyond ordinary constitutional limits, historical precedent, and political good judgment.

The memos, in effect, confer summary legalization on millions of illegal immigrants and institutionalize a set of priorities that excludes millions more in an effort to consolidate that understanding as the legal framework for future immigration enforcement.

Going forward, any illegal alien who overstays his visa or is not caught when crossing the border will in effect have achieved the legal status of being non-deportable. So when the president says of his executive actions that, "It doesn't apply to anybody who's come to this country recently, or who might come illegally in the future,"110 he is being disingenuous. The priorities he is attempting to establish with his executive amnesty memos will continue to be the standard operating procedure for immigration enforcement unless and until they are reversed.

The president's executive amnesty memos have the consequence, and perhaps the intent, of essentially nullifying ordinary immigration law enforcement. As Daniel Patrick Moynihan observed about the trajectory of American culture in 1993, they "define deviancy down"; in this case illegal migration/immigration law breaking.111

Or, as one independent analysis put it, "Obama's administration will order immigration agents to prioritize deportations of criminals and recent arrivals — and let people who are not on that priority list go free."112

These executive immigration amnesties envision, and are designed to bring about, a future in which there are no illegal aliens, and almost all those who come here illegally will have access to the administrative means to change their immigration status to "legal". If the president and his administration are successful it will mark the end of immigration enforcement as we have known it.

Next: "Countering Executive Amnesty, Pt. 2: Foundations of a Counter Strategy"

End Notes

1 White House, "Remarks by the President in Immigration Town Hall", Nashville, Tenn., December 9, 2014.

2 Jeff Sessions, "News Release: "Sessions Says Congress Must Fight Executive Amnesty: 'This Cannot Stand. It Will Not Stand'", July 31, 2014.

3 Charles, Lane, "On immigration reform, President Obama as emancipator?" , The Washington Post, August 6, 2014.

4 John Merline, "63% Oppose Obama Executive Order On Immigration", Investor's Business Daily, August 29, 2014.

5 Although it was billed as "An Address to the Nation", it was carried live only by Spanish-language media because the White House apparently did not officially request prime-time coverage on the networks. See Ben Kamisar, Jesse Byrnes, and Justin Sink, "Networks won't air Obama speech", The Hill, November 19, 2014; see also Byron Tau and Joe Flint, "Many TV Networks to Skip Obama Immigration Speech", Wall Street Journal, November 20, 2014.

6 "Remarks by the President in Address to the Nation on Immigration", the White House, November 20, 2014.

7 Presidential memoranda have the legal force of an executive order, but are distinctive in several ways, among them that they are "formal directives (generally styled as memoranda to the heads of departments) instructing one or more agencies to propose a rule or perform some other administrative action within a set period of time." The question of whether Congress or the president has final authority over agency heads is an open and unresolved question; see Elena Kagan, "Presidential Administration", Harvard Law Review, 114, 2000-2001, p. 2285. See also Jessica M. Stricklin, "The Most Dangerous Directive: The Rise of Presidential Memoranda in the Twenty-First Century as a Legislative Shortcut", Tulane Law Review, 88:2, 2013-2014, pp. 397-412.

8 "Presidential Memorandum — Creating Welcoming Communities and Fully Integrating Immigrants and Refugees", the White House, November 21, 2014.

9 "Presidential Memorandum — Modernizing and Streamlining the U.S. Immigrant Visa System for the 21st Century", the White House, November 21, 2014.

10 Jeh Johnson, "Policies for the Apprehension, Detention and Removal of Undocumented Immigrants", Department of Homeland Security, November 20, 2014.

11 Jeh Johnson, "Personnel Reform for Immigration and Customs Enforcement Officers", Department of Homeland Security, November 20, 2014.

12 Jeh Johnson, "Exercising Prosecutorial Discretion with Respect to Individuals Who Came to the United States as Children and with Respect to Certain Individuals Who Are the Parents of U.S. Citizens or Permanent Residents", Department of Homeland Security, November 20, 2014.

13 Jeh Johnson, "Secure Communities", Department of Homeland Security, November 20, 2014.

14 Jeh Johnson, "Memorandum on Southern Border and Approaches Campaign", Department of Homeland Security, December 20, 2014.

15 Jeh Johnson, "Expansion of the Provisional Waiver Program", Department of Homeland Security, November 20, 2014.

16 Jeh Johnson, "Policies Supporting U.S: High-Skilled Businesses and Workers", Department of Homeland Security, November 20, 2014.

17 Jeh Johnson, "Families of U.S. Armed Forces Members and Enlistees", Department of Homeland Security, November 20, 2014.

18 Jeh Johnson, "Directive to Provide Consistency Regarding Advance Parole", Department of Homeland Security, November 20, 2014.

USCIS regularly grants advance parole to individuals with certain types of temporary status or with pending immigration applications." Further, "In April 2012, the Board of Immigration Appeals issued the precedent decision Matter of Arrabally (later amended in August 2012), which held that individuals who travel abroad after a grant of advance parole do not effectuate a "departure ... from the United States" within the meaning of section 212(a)(9)(B)(i) of the Immigration and Nationality Act (INA). That provision, along with section 212(9)(B)(i)(I), establishes the "3- and 10-year bars" for persons who have "departed" after more than 180 days of unlawful presence in the United States.

This memo directs that clarification of what "departure" means and when it applies.

19 Jeh Johnson, "Policies to Promote and Increase Access to U.S. Citizenship", Department of Homeland Security, November 20, 2014.

20 See Michael D. Shear and Robert Pear, "Obama's Immigration Plan Could Shield Five Million", The New York Times, November 19, 2014. The Times article includes a graph that estimates the numbers of those who might benefit.

Other estimates of the numbers that could be covered can be found in Randy Capps and Marc R. Rosenblum, "Executive Action for Unauthorized Immigrants Estimates of the Populations that Could Receive Relief", Migration Policy Institute, September 4, 2014.

21 David Nakamura, Robert Costa and, David A. Farenthold, "Obama announces immigration overhaul shielding 4 million from deportation", The Washington Post, November 20, 2014. An accompanying article/graph also estimates of the numbers of persons that might gain legalization. See Kennedy Elliott and Dan Keating "Parents, Young immigrants favored in executive action", The Washington Post, November 20, 2014. See also Jens Manuel Krogstag and Jeffrey S. Passel, "Those from Mexico will benefit most from Obama's executive action", Pew Research Center, November 20, 2014.

22 Michael A. Memoli and Lisa, Mascaro, "Republicans want to oppose Obama on immigration, but how?" , Los Angeles Times, November 22, 2014.

23 "'This Week' Transcript: President Obama", ABC News, November 23, 2014. Elsewhere the president has said inaccurately, "These are the kind of lawful actions taken by every president, Republican and Democrat, for the past 50 years." See Office of the White House, "Remarks by the President in Immigration Town Hall", Nashville, Tenn., December 9, 2014.

24 Glenn Kessler, "Fact Checker: Obama's claim that George H.W. Bush gave relief to '40 percent' of undocumented immigrants", The Washington Post, November 24, 2014.

25 Editorial, "President Obama's unilateral action on immigration has no precedent", The Washington Post, December 3, 2014.

26 Alicia A. Caldwell, "Experts: Obama can do a lot to change immigration", Associated Press, August 4, 2014. Said Caldwell, "After a broad immigration bill failed in 2007, President George W. Bush ordered his staff to come up with every possible change he could make without the approval of Congress. Gregory Jacob, who worked on immigration issues with the president's Domestic Policy Council, said the list included similarly broad protections from deportation as those implemented by Obama. But Bush's staff concluded that the president didn't have the legal authority to grant such 'sweeping and categorical' protections." (Emphasis added.)

27 Michael D. Shear and Julia Preston, "Obama Pushed 'Fullest Extent' of His Powers on Immigration Plan", The New York Times, November 28, 2014.

28 That memo builds on a previous DHS memo detailing their new "southern strategy." See Jeh Johnson, "Memorandum for DHS Leadership: Strengthening Departmental Unity of Effort", Department of Homeland Security, April 22, 2014.

29 Margo Schlanger, "A Civil Rights Lawyer Explains Why Obama's Immigration Order Is an Even Bigger Deal Than It Seems", The New Republic, November 25, 2014.

30 "In 2012, the GAO found that levels of satisfaction and engagement varied across components, with some components reporting scores above the non-DHS averages. Several components with lower morale, such as Transportation Security Administration (TSA) and Immigration and Customs Enforcement (ICE), made up a substantial share of FEVS respondents at DHS, and accounted for a significant portion of the overall difference between the department and other agencies." See GAO, "Department of Homeland Security: Taking Further Action to Better Determine Causes of Morale Problems Would Assist in Targeting Action Plans", September 28, 2012, p.1. Similar findings were reported the following year; see Statement of Director Homeland Security and Justice Issues David C. Maurer, "Department of Homeland Security: DHS' Efforts to Improve Employee Morale and Fill Senior Leadership Vacancies", GAO, December 12, 2013.

31 ICE personnel have filled lawsuits against the agency claiming retribution for speaking out against the widening of administrative discretion. In ones case, "U.S. District Judge Reed O'Connor, who earlier this year had expressed agreement with the agents' contention that the deferred deportation program undermined their duty to enforce the law, said on Wednesday that it was not within his court's jurisdiction to decide on what essentially is a dispute between federal employees and their employer, the U.S. government." See Elizabeth Llorente, "Judge Dismisses ICE Agents' Lawsuit Challenging Obama's Deferred Action", Fox News Latino, August 1, 2013.

32 "Provisional Unlawful Presence Waivers of Inadmissibility for Certain Immediate Relatives-Final Rule", Federal Register, January 3, 2013.

33 Jeh Johnson, "Expansion of the Provisional Waiver Program", Department of Homeland Security, November 20, 2014, p. 2.

34 Office of the White House, "Remarks by the President in Immigration Town Hall", Nashville, Tenn., December 9, 2014. (Empahsis added.)

35 The original 3/10 year bar law was watered down after it passed the House and then adjudicated in a House-Senate Committee conference. It's impact was further hobbled by a series of ruling made by the INS that restricted its application. See Jessica M. Vaughan, "Bar None: An Evaluation of the 3/10-Year Bar", Center for Immigration Studies, July 2003.

36 One component of this memo expands the 2012 DACA program (Deferred Action for Childhood Arrivals) to remove the age cap (31 years of age is no longer the ceiling), extends the length of this status for three years from two, and adjusts the date from which the applicant must have been in the United States from June 15, 2007, to January 1, 2010.

37 Jeh Johnson, "Policies for the Apprehension, Detention and Removal of Undocumented Immigrants", Department of Homeland Security, November 20, 2014.

38 After making the limited resources argument repeatedly, the office of Legal Council in its memo justifying the president's actions adds this, "DHS does not, however, attempt to justify the proposed program solely as a cost-saving measure, or suggest that its lack of resources alone is sufficient to justify creating a deferred action program for the proposed class. Rather, as noted above, DHS has explained that the program would also serve a particularized humanitarian interest in promoting family unity by enabling those parents of U.S. citizens and LPRs who are not otherwise enforcement priorities and who have demonstrated community and family ties in the United States (as evidenced by the length of time they have remained in the country) to remain united with their children in the United States. See Office of Legal Council, "The Department of Homeland Security's Authority to Prioritize Removal of Certain Aliens Unlawfully Present in the United States and to Defer Removal of Others", November 19, 2014, p.26. (Emphasis added.)

39 Department of Homeland Security, "Fixing Our Broken Immigration System Through Executive Action — Key Facts", December 5, 2014.

40 Office of the White House, "Remarks by the President in Immigration Town Hall", Nashville, Tenn., December 9, 2014. See also the following: "And we'll keep focusing our limited enforcement resources on those who actually pose a threat to our security." Office of the White House, "Remarks by the President on Immigration — Chicago, Ill.", November 25, 2014.

41 Quoted in Alicia A. Caldwell, "Experts: Obama can do a lot to change immigration", Associated Press, August 4, 2014.

42 Mr. Rodríguez's written testimony may be found at "Oversight of U.S. Citizenship and Immigration Services before the House Committee on the Judiciary on July 2014 by USCIS Director León Rodríguez", July 29, 2014.

43 John Morton, "National Fugitive Operations Program: Priorities, Goals, and Expectations", December 8, 2009, p. 2.

44 Joseph Tanfani and Brian Bennett, "Number of immigrants deported from U.S. dropped sharply in last year", Los Angeles Times, December 6, 2014.

45 Joseph Tanfani and Brian Bennett, "Number of immigrants deported from U.S. dropped sharply in last year", Los Angeles Times, December 4, 2014. That news report contains, embedded in it, a link to the actual Border Report.

46 Julia Preston, "Court Deportations Drop 43 Percent in Past Five Years", The New York Times, April 16, 2014.

47 See John Morton, "National Fugitive Operations Program: Priorities, Goals, and Expectations", U.S. Immigration and Customs Enforcement, December 8, 2009; John Morton, "Civil Immigration Enforcement: Priorities for the Apprehension, Detention, and Removal of Aliens", June 30, 2010; John Morton, "Civil Immigration Enforcement: Priorities for the Apprehension, Detention, and Removal of Aliens", March 2, 2011; John Morton, "Exercising Prosecutorial Discretion Consistent with the Civil Immigration Enforcement Priorities of the Agency for the Apprehension, Detention, and Removal of Aliens", June 17, 2011; John Morton, "Civil immigration Enforcement: Guidance on the Use of Detainers in the Federal, State, Local, and Tribal Criminal Justice Systems", December 21, 2012. See also Peter Vincent, "Case-by-Case Review of Incoming and Certain Pending Cases", November 17, 2011.

48 Aaron Blake, "How immigration reform is winning, even while it's still losing", The Washington Post, December 5, 2014. That article refers to a survey conducted by the Public Religion Research Institute that found that 71 percent of its respondents felt the system was "broken". No questions were asked about what the term meant. See PRRI Religion & Politics Tracking Survey, December 4, 2014.