Download a pdf version of this Memorandum

The 9/11 Commission recommended a biometric screening system for foreign visitors, upon both entry to, and exit from, the United States.

In the wake of the Christmas Plot and the near-getaway by would-be Times Square bomber Faisal Shahzad (who had already boarded a flight leaving the United States when he was arrested), we are once again reminded that border security is an essential element of national security, and exit control is part of that rubric. For 14 years, various laws requiring exit control have sat on the books. There have been discussions, policy platforms, even pilot programs, but to this day, we do not have a full-fledged Exit program covering both air and land ports of entry.

To promote robust discussion of the politics and practicalities of implementing Exit, the Center for Immigration Studies’ Janice Kephart and Jessica Vaughan took the lead in bringing together some of the most important thinkers and decision makers with very different views on the issue. The June 2 program was invitation-only and off the record, with no media. This report is a summary of those discussions. Each panelist has reviewed and approved his or her comments as reported herein.

Background. While US-VISIT’s Entry program was able to get up and running within a few years after 9/11, a corollary Exit program has never gotten beyond the pilot stage, despite widespread congressional support. Part of the reason is political and financial, but it is also because on a practical level, Entry had the advantage of a pre-existing infrastructure at our air, sea, and land ports of entry, whereas no corollary infrastructure exists for Exit.

Exit is also tied to policy and program issues, each with a set of sub-issues that remain at best confused and unsolved, and a political community frustrated and the American people wondering at the delay and government red tape. Program issues pertaining to Exit include whether it should be implemented within the US-VISIT program or as part of another DHS component; the Visa Waiver Program; our national views on identification, biometrics, and privacy; government allocation of resources and infrastructure that differ substantially between air and land ports of entry; and what to do with the data (real-time or otherwise) once the federal government has it.

Among the policy questions: should Exit be designed as a tool simply to curtail overstays and illegal immigration, or is there a greater value to national security? Can it do both simultaneously? Does it need to stay tied to the Visa Waiver Program? Must the Exit system be biometric (using fingerprints or photographs) or would a biographic system (tracking just names and paperwork) be sufficient? Where will the money come from to build a biometric program that US-VISIT projects would cost $1.3 billion to $2.8 billion and how will it be maintained? And are we willing to provide long-term funds for the personnel required to run Exit as well as the long-term funds to find, detain, and deport those identified as overstays?

There are also overlapping laws governing Exit implementation, further complicating its situation. But despite it all, Congress, and those involved in the Exit symposium, tend towards agreement that Exit can be valuable for both immigration enforcement and security purposes. However, these objectives can be in conflict (although they need not be). All agreed that the purpose of Exit must be clearly defined. The group also agreed on the need to break the Exit problem down into manageable pieces, especially given the universally acknowledged challenges at the land border.

The most manageable point to begin Exit implementation is likely airports, as shown in the most recent June 2009 pilot programs at Detroit and Atlanta international airports. Airlines refused to participate in the pilot programs, reiterating the emerging agreement that Exit, like entry, is primarily a government function. Both programs successfully used border inspection personnel to take biometric Exit data, at the jetways (in Detroit) and TSA checkpoints (in Atlanta).

On the issue of facilitation of travelers, both pilot programs had near-perfect compliance and did not create longer lines or result in missed flights. On issues of program mission, both pilot programs found high rates of overstays and considerable watch-list hits, fulfilling both immigration and security functions simultaneously.

Opinions of symposium participants diverged, however, on whether DHS should implement a new biometric system or continue to enhance its biographic efforts, even though all acknowledged there is wide bipartisan support, and demand in Congress, for a biometric Exit. If resources were not an issue, a biometric-based Exit system is the preferred solution. However, given fiscal and other realities, the costs of implementing and maintaining a biometric Exit program may outweigh the benefits.

Keynote: Are We Ready for Exit?

Leon Fresco is the Immigration Counsel (Majority) to the U.S. Senate Judiciary Subcommittee on Immigration, Refugees and Border Security.

Fresco is perhaps the key immigration counsel in the U.S. Senate, as Sen. Schumer is currently the leader on “comprehensive immigration reform” (CIR) efforts. Fresco’s participation in CIS’ Exit event, according to Fresco, underscores Sen. Schumer’s belief that CIR cannot happen without embedding enforcement measures into the legislation, and one such element of that is an operational Exit system for all foreign nationals at land and air borders. Fresco told the group that Exit is increasingly popular on the Democratic side of the aisle.

More specifically, Fresco sees an Exit program as part of “holy trinity” to show the American people that border security is being taken seriously. The three elements to this trinity are: (1) securing the physical border; (2) employment authorization for a legal workforce; and (3) tracking entry and exit. Without all three in place, according Fresco, it would be difficult to achieve CIR. However, because of the stagnation of the Exit program, Fresco suggested that any “comprehensive immigration reform” bill include implementation of an Exit program.

Fresco acknowledged that outstanding questions remain regarding Exit implementation, and broke them down as follows as current status of (1) implementation and pilots; (2) technology that is fast, accurate and useful; (3) and budgets and cost projections.

In addition, what are the policy objectives we want an Exit system to accomplish? If it is simply to control illegal immigration, we are better off with a biometric Social Security card. If it is national security, it must happen with a CIR. Then the next questions are how do we get Exit system to air, and then land? And what is the process by which we accomplish that goal?

How to Accomplish Exit. We need to start with air entry, and move to land borders. As foreign national enters the U.S., a biometric record is taken. If granted entry, the biometric is assigned a length of stay expiration date. Upon exiting the U.S., each person would provide the same biometric they did upon entry. The database holding the biometric alongside the entry and exit dates would “check off” the exit, verifying legal departure.

If a biometric is not given –if, for example, the foreign national fails to exit and overstays – that data would be added to a national criminal database for detention and removal. An issue here is the leeway provided to the alien who does depart, but does so late. What if the alien had stayed because he filed for a change of status and then was refused, but doesn’t find out until long after he is an overstay; how does the system handle these anomalies? How long would the overstay need to be to qualify for the criminal database? Would we wait for an encounter with local police, or send immigration agents to pick up the individual? The bottom line is that the system needs to worry about long-term overstays, not short-term. Building in a buffer for short-term over stays is thus important.

Surely a few days or weeks should not be sufficient to trigger consequences, and an exit system would require clear regulatory (or otherwise) guidance. This issue must be addressed, as the most recent pilot found a significant issue with overstays boarding flights departing the U.S.

Detroit and Atlanta Pilot Programs. The pilots at Detroit and Atlanta in June 2009 worked relatively well. Fresco pointed out that if the biometric Exit is done at the gate, as was done in Detroit, it is “demonstrably effective” – that person has certainly boarded. Schumer, however, would prefer biometric to be done inside the plane, as when buying a snack. This would eliminate last minute jetway checks of late travelers by CBP. Essentially, Fresco argued, if the penalty for overstay a visa is bad enough, people will want to swipe their information on the plane. However, it also means that airline personnel, not government employees, would be taking sensitive data and transferring it back to the government.

Land Border Issues. With New York State sharing a long and busy border with Canada, assuring a solid Exit program that does not choke commerce and may actually reduce crossing time is key. A clear goal is to never stop people from leaving. As to Mexico, a U.S. Exit program will be “more palatable because of the unique factors of Mexican border.” For example, if we are stopping the car to go into Mexico to pay a fee or be checked for guns, would we be able to scan at the stop? Mobile scanners take about only take about 30-45 seconds. Fresco believes a Trusted Traveler-style Exit is feasible, but the financial commitment will not be there without CIR or another terrorist attack that proves that overstays can be a national security threat.

Biometric or Biographic? A biometric system seems inevitable. It needs to be part of a CIR. Fresco pointed out Sen. Schumer’s perspective that E-Verify does not work well enough because law-breaking employers and illegal aliens can easily collude to bypass E-Verify, making an illegal alien appear to the system as legal. Anyone with $5000 to hire a smuggler has enough money to get a fake Social Security card. Only a biometric solution will suffice to shore up unauthorized employment, even if it would be nice if biographic covered the spectrum of fraud sufficiently.

Budget and Cost. Will Congress justify Exit financially? It is not feasible to charge foreign nationals to Exit, as that provides disincentive to legal immigration. However, biometric is so much better than biographic, that a biometric Exit requires funding. However, Fresco does not see Congress as willing to fund a $10 billion Exit program without CIR, or some kind of attack/external event that motivates Congress to spend $10 billion dollars. Schumer would prefer a biometric employment system if no other option was available, and get the system right from the beginning.

During the Q&A, Fresco was asked whether Schumer had spoken with the airlines regarding their willingness to do an on-board biometric Exit. Fresco said Schumer had had such meetings, and the short answer is that the airlines do not want to do it, but that does not mean they cannot be forced or given financial incentives to do it.

Panel I: The Politics and Practicalities of Implementing Exit

Stewart Baker, former DHS Assistant Secretary for Policy

Patty Cogswell, DHS Acting Deputy Assistant Secretary for Policy, Screening Coordination Office

Two senior congressional staff members (Majority and Minority from both the U.S. House of Representatives and U.S. Senate) agreed to participate off the record

Moderator: Janice Kephart, Director of National Security Policy, CIS

Janice Kephart: There has been much ado in the last 10 years over implementation of an Exit program. Congress, the 9/11 Commission, and Congress again, and again, have layered on requirements and missions for such a program. The issue has waxed and waned, and its history is a bit complicated. Below is a short history of where we are now with Exit and how we got here.

In the post-9/11 era, the issue of national security and biometrics has been a big one. The issue has never failed to engage Congress. In 2000, two separate laws were passed, one that set up Exit and the other that tied it to the Visa Waiver Program. In 2001, the USA Patriot Act chimed in again, demanding Exit. In 2002, the Border Security Enhancement law again required Exit, and in 2004, the intelligence reform act emanating from 9/11 Commission recommendations included it again. Beginning in 2004, and until 2007, pilot programs for Exit were undertaken at the demand of Congress. The technology worked, but compliance rates were low since the kiosks were not manned by government and not clearly mandatory.

Then in 2007, the 9/11 Commission Recommendations Act reiterated the need for Exit and required Exit apply to all foreign nationals entering under the Visa-Waiver Program, adding in a biometric component. The basic idea behind a biometric Exit requirement was to reassert the 9/11 Commission recommendation that the federal government assure that people are who they say they are in real time, and that no derogatory information be linked to them to prevent departure.

Data gathered – depending in part on whether the data was gathered and vetted in real time – would provide overstay data and watchlists hits. Overstays would give CBP and State better data to determine who gets to visit us again, and ICE better information about who returned or illegally overstayed. Exit data may even give Joint Terrorism Task Forces the ability to curtail terrorist absconders who sought to slip out of the U.S. unnoticed based on verified watchlist hits – akin to what we saw with the Times Square bomber – or those of us on the 9/11 Commission staff hoped. US-VISIT, the DHS program that takes 10 fingerprints and a digital photo of foreign nationals when they enter the country, seemed the perfect fit to do a biometric Exit.

Then in 2008, DHS put out a proposed rulemaking for the “Collection of Alien Biometric Data Upon Exit From the United States at Air and Sea Ports of Departure,” but it put the onus on airlines to collect biometric data anywhere in the international departure process, with no money. The airlines balked. A viable Exit system was far from implementation.

In 2009, congressional appropriators, clearly frustrated by the lack of progress in implementing Exit, required two airport pilot programs before appropriating money for a fully implemented Exit.

In June 2009, US-VISIT conducted the required pilots at Detroit and Atlanta. One tested TSA checkpoints, the other required CBP to screen departures on the jetway. Both went very well, with no increase in processing time that amounted to missed flights, or even flow time or longer lines. Those processed complied. Overstays and watchlists hits were found. The technology worked. Overall, the Air Exit pilots confirmed the ability to biometrically record the Exit of those aliens subject to US-VISIT departing by air.

In October 2009, the appropriations committees received the evaluation report from US-VISIT as required by law. What awaits then, since October of last year, has been a decision from Secretary Napolitano on the what, when, and where of an Exit program. While other nations, like Australia, have made a biographic Exit part of their immigration controls for years, and it simply isn’t a big deal, issues of money, politics, and practicalities of infrastructure have haunted this issue for the last 14 years in this country.

Patty Cogswell: From DHS’s perspective, there are two primary potential mission areas for Exit: immigration control and security. For example, if Exit is intended to identify an alien who has definitely departed the United States, the concept of operations may be different than if the objective of Exit is to help law enforcement officers intercept criminals or terrorists before their departure. The preferred policy objective will drive the Exit solution.

If the government’s interest is in departure assurance, then we need a controlled airport departure zone with a visible collection of biometric data using agreed upon technology that is (1) clearly visible; (2) consistent; but (3) necessarily expensive if implemented in all Exit points.

If our interest is security or law enforcement, then a fixed, standardized Exit will not find people seeking to evade and hide from the system, nor find and remove individuals from the U.S. who have overstayed. Moreover, a security-oriented Exit requires extra time, according to Cogswell, and therefore a different configuration. Thus, having an Exit zone integrated as early into the departure process as possible would be best to ensure the greatest opportunity to interdict and possibly apprehend a subject prior to departure. The closer the Exit is to departure, the less time DHS has to respond to any matches.

Today, DHS collects biographic information for air Exit. Air carriers transmit their passenger information to DHS for individuals departing the U.S. DHS analyzes this information to determine who has overstayed the terms of their admission, creates lookouts for those who are confirmed overstays, and refers information to ICE field offices for investigation based on threat priority, for individuals who appear to have overstayed and are still in the U.S.

DHS has made significant efforts, including many pilots. However, there is as yet no decision by the administration as to when or how, or if, Exit will be implemented.

Stewart Baker focused his comments on lessons learned from the Christmas Day bomber, in light of the Exit pilot conducted at a TSA checkpoint in Atlanta in 2009. He highlighted problems with the TSA system, and strongly suggested that TSA would provide more robust screening if informed by a review of travel documents being integrated into their screening process. Such review could double as a biometric Exit. Such a view is buttressed by the June 2009 pilot in Atlanta, said Baker. The TSA pilot found no problems with compliance, longer lines, or border inspection cooperation and management alongside TSA personnel. If the immigration processing were integrated into aviation security processing, aviation screening would be stronger, plus our nation would finally fulfill its Exit mandate.

According to Baker, there was plenty of information on the Christmas Day bomber, but TSA, unlike CBP, does not utilize such information in its screening decisions. CBP, which does have access to the information for screening decisions, had already flagged Abdulmutallab for secondary screening. However, CBP does not usually make decisions about whom to screen until a plane is in the air – and it has not until recently used such data to screen international passengers before they board the plane. Thus, neither of the two agencies that are the last line of defense against a terrorist boarding an aircraft truly have sufficient information to assure aviation security prior to takeoff. The only exception was if the foreign national is a citizen of a visa-waiver country where CBP now vets passengers days or hours prior to travel, requiring those that are “hits” on watch lists to obtain a visa and undergo greatly scrutiny prior to arrival at an airport. (CBP and TSA have begun to work together to use CBP resources and data access to add a layer of questioning to the process of boarding a limited number of transatlantic flights, but this is an ad hoc and resource-constrained measure.)

Right now, TSA functions are limited by law and regulation. In addition, we ask the airlines to take much of the responsibility for federal government functions, including checking the passenger’s identity document for purposes of cross-referencing the no-fly list. If the airline is lax in compliance (e.g., slow to update the no-fly list, or sloppy about reading passports), security is potentially compromised. In contrast, CBP integrates a passport scan into its screening at the border. However, this screening occurs at the border, after the plane has landed. Before boarding, TSA cannot use identity and travel information to inform its screening process – except through the airline identity check and the crude mechanism of the no-fly list.

Baker explained that from his point of view, TSA security is a strange hybrid between airlines and government, whereby the government puts out threat and watch list information, and the airlines run their passenger data against the government databases. Only now, all this time after 9/11, are we moving in the direction of government, through TSA, beginning to acquire passenger names directly from airlines and doing the vetting of those names only to return “hits” to the carriers through TSA’s Secure Flight program. Secure Flight is finally relieving airlines of the requirement to timely download threat information and run manifests against new and existing watch list information. (The Times Square bomber, Shahzad, should have been caught by the airline at the ticket counter but the airline had failed to quickly upload the latest threat/watch list information. Only when CBP received the passenger manifest was he caught.)

Yet Secure Flight is only part of the solution. TSA still relies on the airline for implementation of security measures. The airline scans the ID, the airline marks the passenger’s boarding pass with a “mark of Cain” if the passenger is a selectee. Because these steps are separate from the TSA screening process, there is no way to use all available government intelligence about possible terrorists in deciding how much screening to give a passenger.

Airlines should not be in the business of conducting security. What the government should do is use the TSA checkpoint in two ways: physical and identity screening, which could integrate an Exit component. By checking travel documents more robustly, two purposes could be served: (1) accumulate Exit data; and (2) determine if additional screening is necessary based on any anomalies with the travel document and biometric match to entry data, as well as any behavioral issues. This would replace the two-tiered method being used today: blind “random” screening being used alongside secondary screenings based on the selectee list.

Essentially, a revamped TSA system could meet the goals of Exit, killing two birds with one stone. In addition, TSA would be privy to the immigration, travel document, and watch list information only CBP has access to today, better informing secondary screening decisions. There are potential issues here, however. A TSA checkpoint could amount to a check that the passenger has departed the country, when in fact a foreign national could simply turn around after screening and leave the gateway immediately. However, if that happens, the flight manifest list would pick up the anomaly.

What are the compromises and problems? It will be difficult to reconcile TSA and CBP procedures when CBP is largely governed by the Judiciary and Finance committees (as well as Homeland Security) while TSA is overseen by Transportation and Homeland Security. TSA does not have an immigration function and CBP does not have an aviation security function, and both agencies may well resist a merger. Such complications can be overcome, however, with sufficient will.

We also have to resolve what biometric feature is acceptable under the law. A fingerprint is what US-VISIT holds for a foreign national’s entry, as well as a digital photo. Do we need the fingerprint for the departure process, or would a biometric facial scan be acceptable?

Baker stated that fingerprints add a little, but only a little, to the accuracy of passport-based systems that check the photo in the passport. In the end, fingerprint checks will probably never be feasible at the land border, but they are feasible in an air security environment. Whether we need to implement fingerprints immediately is an open question given their modest additional value in confirming ID. The key is to take control of the ID process and to integrate Exit and air security measures as soon as possible before we have another Christmas Day-type bomber. Once that is done, fingerprints can be implemented if they are necessary. We should not devote too much effort on designing an absolutely escape-proof Exit recordkeeping system. Instead we should keep our eye on the security ball. There are manageable ways to get a workable Exit system that adds to security, and we just need to do it.

Two Senior Congressional Staffers agreed to combine their remarks but not be otherwise identified. One is staff for the U.S. Senate Minority, the other staff for the U.S. House of Representatives Majority.

Both staffers emphasized that the post-9/11 programs, like US-VISIT, have worked because they were implemented piece by piece. There is no difference with Exit. The entire program must be grounded in practicalities. Congress has mandated Exit multiple times, and DHS simply needs to make the decisions necessary to put together a viable plan that will enable it to be funded. Whether or not DHS or CBP wants to do Exit is irrelevant; CBP resisted US-VISIT in 2003, and now embraces the program.

However, until there is consensus on the necessary phases of Exit implementation – not just in its technical components, but how Congress will see it come into implementation – Congress cannot take DHS seriously nor provide for appropriations.

Both staffers stated that the Obama administration is taking what should be a very practical decision and blowing it up unnecessarily, and suggested that the current administration, like the last one, is using indecision on mission to buttress a refusal to come up with a viable plan. Both staffers said all that is needed is to break an Exit down into pieces, start with most vulnerable places (air), and then work down.

Both staffers also pointed out that DHS currently has in reserve over $50 million (billions more is likely required for full biometric implementation) for DHS to start the process of implementing Exit as required by law – gathering biometric, biographic, and departure information. Biometric is essential to fill the gaps against fraudulent use of passports or identities on Exit, and other abuses that stem from only using biographic information. For national security and immigration purposes, it is thus essential to maintain a biometric element to an Exit program.

One of the staffers emphasized that there was never complete consensus on what the air and sea entry phase of US-VISIT should look like, yet it still got done and is successful because the practicalities of the program were well laid out.

A good plan is essential for Exit more because it is a high cost issue at this point, especially due to resource challenges to man the program in the long run. The existing $50 million is only enough for planning or another pilot. Pilot programs were not a department initiative, they were a statutory requirement. The pilots were useful in that data is now available, but the airlines’ unwillingness to participate was not helpful.

What we do know is that the number of overstays is growing, putting more pressure on ICE and the State Department to figure out data that should be at their fingertips with an Exit that should be in place. Only now is State beginning to get decent biographic overstay data. The technology for biometric Exit, after these 14 years, is now not really issue. The issue is really one of political will.

Personnel resources to man Exit are the real cost issue over the long haul, as the airlines will continue to refuse to participate; that is unlikely to change.

The other staffer emphasized that if the issue is now one of DHS believing that biographic Exit is sufficient, then a proposal to repeal a biometric Exit must be put forth by the administration, especially if we determine that the return on investment in a biometric system is not worth the cost to build it.

Panel II: Exit in the International Community

Jim Williams, Minister/Counsellor, Immigration, Embassy of Australia

Christopher Sands, Senior Fellow, Hudson Institute

Jena Baker McNeill, Homeland Security Policy Analyst, The Heritage Foundation

Moderator: Janice Kephart

Janice Kephart set the tone by commenting that as a nation, we cannot forget that while the U.S. is the user of the departure data, our foreign friends are the subjects of the data. We also cannot forget that while implementing an Exit program seems a near-impossible quest, that’s not the case elsewhere.

In Australia, for example, Exit controls are an integrated part of their operations at airports. Here in the U.S., we have 228 international air ports of departure, but we also have much heavier volume on our lands ports of departure, yet no Exit exists at our land ports, either.

On our land borders, our infrastructures are bulging trying to deal with the volume of crossings. With our biggest trading partner being Canada, it will be difficult to implement any type of Exit for departures by land without being in sync with our Canadian neighbors. In addition, our Visa Waiver friends in Europe and elsewhere have seen Congress marry Visa Waiver to an Exit program that does not exist. Visa Waiver allows their citizens to come to the U.S. without a visa. Congress has said, for the Visa Waiver show to go on, we must have a biometric Exit. To some degree, the future of the visa waiver program has been made contingent on the implementation of an Exit program.

Jim Williams began his remarks noting that Australia is lucky to have a more contained port of entry infrastructure than the United States, with only 12 international airports as opposed to the 228 U.S. international airports. In addition, Australia has no land border.

Unlike the U.S., Australia built in an exit control system into its international airport infrastructure. The system is biometric on entry, using facial recognition technology, and biographic on exit. Departure is not considered a security risk – it is really only considered important for immigration control. However, departures are checked against the same database “alerts” as entries are, populated at the discretion of the Australian Federal Police.

The purpose of the Australian exit system is threefold: (1) keep track of who is in the country; (2) gather information on overstays; and (3) match entry and exit numbers, which enables a more accurate setting of visa caps.

Australia law does not enable Australian immigration control to prevent departure, unless clearly delineated by law. Those prevented from leaving generally only fall into two categories: (1) child abduction cases; or (2) outstanding criminal warrants.

The process is relatively straightforward for departure processing. Upon arrival at the airport, the passenger first checks through departure control, staffed by Customs and Border Protection. Foreign nationals present their passport, which is collected and matched against immigration records. A departure card much be completed, and if all paperwork is in order, a departure stamp is placed in the passport book. If an officer receives notification that there is an outstanding warrant, the individual gets notified of anything that would need to be checked (warrants, overstays, people who will need a visa to get back). Once the passenger cards are collected, the data is used to compile statistics and for tourism promotion.

The majority of stops are for those for whom there is an outstanding warrant. Once through departure screening, the airline is required to match person to boarding pass upon boarding, as fraud can enter the system – and does at times – with boarding pass swaps.

One of the main differences between inwards and outwards immigration clearance is that there is no power under the Migration Act 1958 to prevent passengers leaving Australia. However, a passenger’s departure may be prevented by other legislation, such as where a passenger is wanted by the Australian Federal Police or a child’s travel is restricted in relation to custody matters. These referrals would not normally come to the attention of the Department of Immigration and Citizenship (DIAC) at an airport as they would be subject to a Customs alert.

Customs and Border Protection Officers follow a routine when processing passengers on inwards and outwards immigration clearance. The Primary Line Officer (PLO) routine remains the same for both inwards and outwards immigration clearance.

Customs and Border Protection Officers perform a number of processes, some include: identifying the traveller against the travel document; checking the passenger against Customs and Immigration databases; alert checking for both agencies and the Australian Federal Police; processing passengers on behalf of DIAC (as authorised officers under the Migration Act 1958).

PLOs must ensure that a passenger is properly documented when they present for Outwards Immigration Clearance. All passengers must present; Australian citizens must provide evidence of identity, an Outgoing Passenger Card (OPC), and a valid boarding pass. Non-citizens must provide evidence of identity, evidence of a visa, OPC and a valid boarding pass.

All departing passengers must complete an OPC, except for those same persons who are exempt from completing the IPC: operational aircrew members; guests of Government; and domestic passengers. From a DIAC perspective, there is no requirement to check that the OPC is accurate, just completed. However, it is common practice for the OPC to be checked for accuracy.

A passenger should be referred to DIAC if they refuse to: complete an OPC; or answer a part of the OPC which they are required to answer, including signing the card.

There are however, a few slight differences when processing outwards passengers as opposed to processing inwards passengers:

Stamping travel documents on outwards: The major difference is that all passengers must be fully processed before being referred to DIAC. This means that all travel documents should be stamped with the Port and Date stamp (“Departed Australia”) even if they are referred to DIAC, except for: expired travel documents; documents held by suspected impostors; and Australian passports and Documents of Identity (with Citizenship “Australian”). Also, PLOs should NOT use the NVFFT stamp on travel documents of passengers departing Australia.

Summary Line Prompts. There are only two summary line prompts which appear in outwards processing:

- RRV EXPIRED – this prompt informs the PLO that the passenger’s Resident Return visa (RRV) has expired. The PLO must advise the passenger to obtain a new RRV before returning to Australia.

- RRV EXP <2W – this prompt informs the PLO that the passenger’s Resident Return visa (RRV) will expire within the next 14 days. The PLO should advise the passenger of this and advise them if they are offshore when the RRV expires, that they will need to obtain a new RRV to return to Australia.

In either case, should the passenger require further information, the PLO should refer them to DIAC.

The only immigration stamp PLOs have on the outwards primary line is the “Departed Australia” Port and Date stamp. The stamp is used as evidence of departure. The Port and Date stamp should be placed on the first clean visa page of the travel document. Stamping the passenger’s travel document with the departed stamp is the final action required by the PLO.

Chris Sands began his remarks by recalling the historical evolution of Canadian views of our shared border. He reviewed our recent history with the Canadians after September 11 as initially reluctant to consider any measures that added security due to a deep concern that facilitation of trade, commerce, and passenger flows would be significantly and adversely affected. Specifically, for about four years Canada officially opposed the requirement that all incoming arrivals, including at land ports of entry, provide a passport or biometric equivalent, as recommended by the 9/11 Commission.

Prior to 2009, any form of identity card, and even an oral declaration of U.S. citizenship, was potentially acceptable for entry into the U.S. However, since the implementation of the passport requirement known as the Western Hemisphere Travel Initiative, alongside more robust trusted-traveler systems, Canada has noted no negative change in border traffic and extremely high compliance with the requirement. Canada has thus evolved from skeptical to enthusiastic on many security enhancements, including Exit, especially under Prime Minister Harper. The current convergence of views leads to a potential for cooperation, especially if the U.S. is willing to take the lead with implementing Exit on its homeland.

Like Australia, Canada’s main interest in obtaining exit control is immigration-related. While the U.S. has about 400,000 final deportation orders unaccounted for, as of 2007, Canada had 40,000. For the U.S., this represents about 1.3 percent of the U.S. residential population of 310 million, and about 1.2 percent of Canada’s 34 million. Canada remains deeply concerned about being unable to track whether these individuals self-departed or remain in-country.

Canada has learned the value of pre-screening passengers. Canada’s Charter of Rights has long held that anyone standing on Canadian soil has full rights of a citizen, including access to education, healthcare, and the court system. The result has been a huge influx immigration applicants from many countries, but predominantly Mexico. Facing a strain on its resources, Canada elected to use pre-screening to prevent unfettered entry, where intending immigrants are not afforded Canadian rights. All foreign nationals entering Canada now receive pre-screening and U.S. databases are used to provide a more thorough vetting process. In specific response to the substantial Mexican influx, in 2009 Canada began to require visas of all Mexicans prior to travel.

Current issues in Canada pertaining to entry and exit involve use of biometrics and verifying identity; to what extent that data is to be shared with other nations; and land border facilitation concerns.

Canada is interested in the potential for creating a shared U.S./Canada border system, whereby the U.S. Entry would be Canadian Exit and vice versa. Not only would physical infrastructure be shared, but also build a software system whereby the data can be seamlessly interchanged. So while a shared entry/exit system is technically feasible, but issues pertaining to sovereignty – especially if the land used at major ports is in Canada – remain, and personnel exchanges may be necessary to build trust and infuse standard operating procedures.

Jena Baker McNeill’s comments were based in part on her April 2010 paper, “Time to Decouple Visa Waiver Program from Biometric Exit,” http://www.heritage.org/Research/Reports/2010/04/Time-to-Decouple-Visa-W....

The Visa Waiver Program currently permits 36 nations’ citizens to enter the United States without a visa for up to 90 days based on a series of criteria that must be met and maintained to sustain inclusion in the program. McNeill’s paper describes the Visa Waiver Program’s recent statutory changes, including a biometric air exit requirement, as follows:

The Biometric Exit Problem. One of the other important portions of the 9/11 implementation bill was that the Secretary of Homeland Security was given the ability to waive the previous 3 percent visa refusal rate and allow nations with a refusal rate of as much as 10 percent, on two conditions. First, that all other security provisions within the 2007 legislation were met, and second, that DHS implement a biometric air Exit program to screen 97 percent of foreign travelers leaving the U.S. through air travel by July 1, 2009.

While this waiver authority ushered some countries into membership, the failure of DHS to meet the biometric Exit deadline has halted the authority to expand to nations whose visa refusal rate is between 3 and 10 percent.

Linking air Exit to the VWP was billed as a means of decreasing the number of VWP entrants who overstay their terms of entrance. However, while the current total visa overstay rate is 40 percent, only a small number of VWP entrants eventually become overstays. Biometric air Exit, therefore, means very little in terms of security for the VWP.

McNeill claimed that the VWP overstay only approaches one percent, so coupling biometric air exit as a means of dealing with an overstay rate of the remaining 39 percent is insufficiently helpful. An alternative would be to decouple VWP from its statutory biometric requirement under the Implementing Recommendations of the 9/11 Commission Act of 2007. The exit requirement would remain in place statutorily under other laws, but simply be negated out of VWP. Doing so may enable the U.S. to return to a biographic Exit. A better use of resources than a biometric Exit, suggests McNeill, is to focus on more on vigorous immigration enforcement; in other words, removing the incentive to overstay. Full implementation of secure driver licensing under the REAL ID Act of 2005 is a vital component, as that law requires an inclusion of legal status on driver licenses issued to foreign nationals.

Panel III: Implementing Exit: What it Means, What it Should Look Like

Jess Ford, Director of International Affairs and Trade, Government Accountability Office

Harold Woodley, Chief, Public Inquiries Division, State Department’s Visa Office

Jayson Ahern, Principal, the Chertoff Group; former Acting Commissioner, Customs and Border Protection

Julie Myers Wood, President, Immigration and Customs Solutions; former Assistant Secretary, Immigration and Customs Enforcement

Michael Dougherty, Director, Immigration Control, Raytheon Homeland Security; former USCIS Ombudsman and former counsel, U.S. Senate Judiciary Committee

Moderator: Jessica Vaughan, Director of Policy Studies, CIS

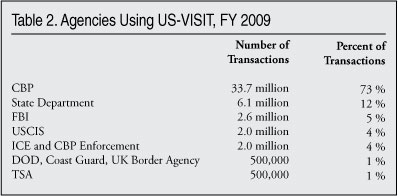

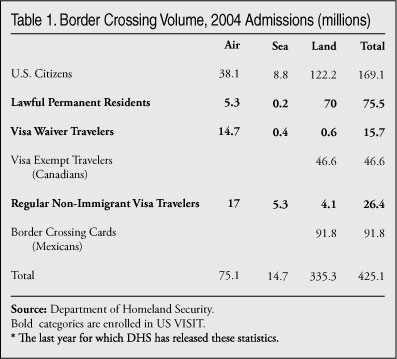

Jessica Vaughan introduced the panel and provided a brief overview of the current scope of US-VISIT. At this time, the program provides biometric entry screening and identity authentication for about one-fourth of the more than 400 million foreign visitors each year – those entering by air and sea. Only a small fraction of those entering by land are fully screened. The land entries, especially of those entering on Border Crossing Cards issued to Mexican visitors, are far more numerous and are believed to be the source of the largest number of visa overstays and visa imposters, as well as a potentially serious security vulnerability. Meanwhile, DHS estimates the total overstay population to be three to four million people, a group sizeable enough to impose significant fiscal, social, and public safety costs on American communities. Ms. Vaughan asked the panelists to share their insights on the potential value of implementing exit controls to the immigration agencies in carrying out their responsibilities and in addressing the overstay problem.

Jess Ford presented the findings of several studies that the Government Accountability Office (GAO) has completed on the magnitude of the overstay problem and on DHS efforts to meet the congressional mandate to implement a biometric exit-control system and report on the size and composition of the overstay population. According to the GAO studies, the government’s inability to control or even track overstays remains a serious vulnerability in our homeland defense. DHS has not yet succeeded in developing a methodology to accurately estimate the number of overstays, but some estimates indicate between 30 and 50 percent of the illegal population could be overstays. Nor has DHS been able to accurately calculate overstay rates for individual countries, which makes it difficult to evaluate the results of admission programs such as the Visa Waiver Program. Mr. Ford noted that previous remarks suggesting that Visa Waiver Program visitors maintain a very low overstay rate of one percent are purely speculative; the GAO report on visa overstays indicated that DHS tracking systems were not sufficient to validate the one percent rate. In addition, the GAO auditors have observed a lack of transparency at DHS with respect to these issues. There have been some improvements; for example, DHS now has improved on previous data collection methods, increased its oversight of the visa waiver program, and improved the process of tracking lost and stolen passports. The GAO is in the process of reviewing DHS progress on implementing an exit-control system; the report will be released by the end of the year.

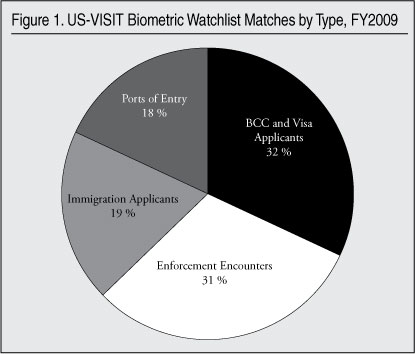

Harold Woodley spoke about the ways in which US-VISIT has dramatically improved the visa operations in U.S. consulates overseas. It is an essential tool in evaluating visa applications and in preventing the entry or re-entry of unqualified or potentially dangerous visitors. Consular officers now can authenticate the identity of applicants and have a reliable record of their visits to the United States. In fact, consulates overseas are the source of largest number of look-out hits generated in US-VISIT (32 percent). Now that some biographic departure data is available from the ADIS system, consular officers also are able to avoid issuing new visas to the travelers who have overstayed, departed, and are now seeking re-entry. Currently, only the fraud officers have direct access to the ADIS information, but the plan is for the information to be accessible eventually at every consular officer’s desk; a pilot project is now underway in San Salvador. Full access to accurate departure information means that consular officers can investigate the travel history of questionable individual applicants and also analyze the overall results of visa issuance decisions. For example, officers will no longer have to conduct crude validation studies, where they try to contact the homes of visa recipients to see if they have returned.

Jayson Ahern addressed the challenges of implementing an exit-control system from the standpoint of U.S. Customs and Border Protection, whose work it affects most directly. He noted that 87 million people arrive or depart by air per year, and that CBP is responsible for all arriving air inspections. But considering that 300 million people arrive or depart by land and sea, in his view a comprehensive system is necessary – meaning that the implementation of an Air Exit program must be immediately followed by an Exit solution in the land and maritime venues. He affirmed that the agency is likely to be supportive of the concept, as long as it does not impact negatively the critical security mission of inspecting people entering the country and as long as the budget, resource and infrastructure needs are addressed. The two Air Exit pilot programs demonstrated that the test at Detroit, whereby passengers were checked out at the jetway by CBP officers with a mobile device that could gather biometrics, would be the more secure option, because it would be done by uniformed CBP officers and because it would provide the most assurance that the traveler actually departed. Mr. Ahern maintained that it would be more appropriate for CBP, rather than TSA, to handle Air Exit, as it already has the presence in most international airports and the in-house knowledge from handling arrivals. However, the Detroit pilot program also showed that CBP airport staffing levels would need to significantly augmented – doubled at least, if not more – to implement this model, as officers would have to cover both arrivals and departures. He said that he hoped policymakers would think through all the ramifications for the agencies involved, and ensure that the resources needed to take advantage of the information generated by an exit system would be provided.

Julie Myers Wood began by pointing out that the information generated by an exit-control system would be useful only if other agencies such as ICE are able to act on it. She offered a number of ideas for how DHS and ICE could use the information for immigration law enforcement, as long as additional resources were made available, and said that a biometric system would be preferable for law enforcement purposes. First, having reliable exit information would mean a more accurate list of potential overstayers for ICE’s 300 compliance enforcement units to deal with. Currently, ICE agents sometimes must spend a great deal of time trying to find out if an individual of interest is still present in the United States. In addition, accurate exit information could help in some criminal cases where ICE needs to establish an individual’s travel history. She said that it would be beneficial to have more ICE agents tasked specifically with locating and removing overstays, but speculated that there might not be great political will for ICE to receive much more funding for that mission. As it is, ICE compliance units have a tough time predicting which individuals out of the tens of thousands of leads they receive pose the greatest potential threat. However, there may be other ways to use the information that will deter overstaying and increase the number who are identified. These include contacting apparent overstayers to warn them that they have been identified and also adding overstayers to existing criminal information databases used by all law enforcement agencies, such as the NCIC. Increasing this type of enforcement may help induce more visitors to comply with the law voluntarily, knowing there are consequences for overstaying, and no such incentive exists today.

Michael Dougherty pointed out that DHS could make better progress if it engaged private industry in developing a solution, as was done for the task of upgrading US-VISIT to 10-fingerprint slap capture. DHS articulated the urgent need and described it as an important national goal, sponsored challenges, workshops, “Industry Days”, and meetings, and was able to acquire the solution in 16 months. Funding from Congress followed shortly thereafter. He said that industry would “leap at the chance” to assist DHS, but needed to know more about what DHS wants. DHS could use modeling and simulation to assist in evaluating options. Mr. Dougherty maintained that the right suite of technologies together with the right policies could overcome the challenges to implementing Exit. He suggested that a suite of check-out options, using different technology, could be deployed, including: kiosks for self-check-out, portable capture devices (the “rental car” method), RFID card technology, and device technology that transmits GPS location outside the United States. As for policy options, DHS should consider giving visitors options, such as confirming departure at a U.S. consulate kiosk with biometric capability, and designating specific ports of exit for particular populations such as guest workers. He speculated that, because Exit has such strong long-time bipartisan and bicameral support, it is unlikely that Congress will abandon the Exit requirement. While he did not recall Exit being considered a bargaining chip in previous negotiations for “comprehensive immigration reform,” its implementation would probably make such negotiations easier, especially if expanded guest worker programs or Visa Waiver program expansions are contemplated.