Costly Border Crossings. The money wasted on operating tiny ports of entry on the northern border, previously described, is diminishing because of the gradual thaw in Canadian border crossing restrictions, but it is still evident.

We noted several months ago that it cost Customs and Border Protection $11,250 per alien inspection to keep the least-utilized port open during the first three months of 2021; this was the one in Ambrose, N.D. Our calculations assumed two agents on duty during each of the 56 hours a week the port was open, and a daily cost of $500 per agent.

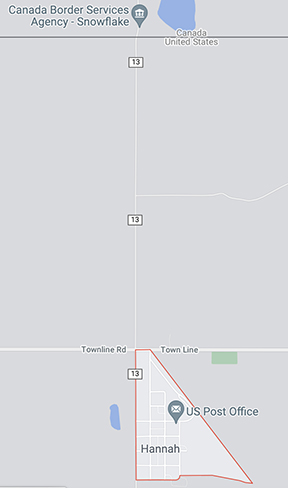

Looking at recently released Department of Transportation data for November, we estimate that the most expensive unit costs are now at the port at Hannah, N.D., where it cost $2,000 per inspection during November, using the assumptions above. During the entire month of November, only 15 crossings were recorded, or one every other day.

The next least-used ports in November included Ambrose, again, with 42 crossings in the month, and Opheim, Mont., which had 60 of them, or about two a day.

We took a closer look at Hannah, with its 15 arrivals in November (and four in February of last year). Google tells us that the population of Hannah, coincidentally, was 15 in the 2010 census. The little town, of 121 acres, is one of the nation’s few municipalities that is triangle-shaped.

We called the port about 4 p.m. on January 5 and asked the agent if he had seen anyone that day. The port was due to shut down for the day an hour later.

“Not a soul,” the agent replied, “It’s blowing up quite a storm.” Google said that the temperature there, at that time, was 21 degrees below zero.

Shutting the port for good would make economic sense, without creating too much of a burden on the sparse, nearby Canadian population. There is another port about 20 miles to the west and another one about an equal distance to the east.

EB-5-Type Programs Elsewhere. The U.S. and Montenegro have little in common beyond being on the same side in WW I. The small country, which sits atop Albania on the map, has about one-seventh the per capita GDP as the U.S., and is a popular tourist destination (I have been there.)

What the two countries also have in common are citizenship purchase schemes for wealthy aliens that come and go. Our EB-5 program died, at least for a while, on June 30, 2021, and theirs was just recently revived by government action, according to an industry website, which reported:

On the eve of the lapse of the legislation on Thursday (30th December) the Montenegrin government made a last-minute ruling that it would extend its economic citizenship programme by one year, until December 2022.

This was despite pushback from the European Commission who argued that it could harm the country’s progress towards EU membership. The government sought to assuage concerns by introducing stricter conditions for gaining economic citizenship through the programme.

We in the U.S. do not have, as Montenegro does, an adult in the room, in this case the European Union. Montenegro, while already in NATO, also wants to join the EU, which apparently is worried about Chinese and Russian investors getting too much influence over the little nation. Apparently, aliens from those two countries dominate the program.

The local government has a provision in its citizenship by investment program that addresses a problem that the U.S. faces, too, and seems to do so in a more appropriate way than we have done in our EB-5 program.

The problem: Some parts of each country need investment more than others.

The answer in the U.S. was that each potential investment was to be in a targeted employment area (TEA) that was defined by the investor (which has led to all sorts of economic gerrymandering).

The answer in Montenegro was that the government divided the country into two regions, the aliens have to put up 250,000 euros for investments in the north, where they are more needed, or 450,000 Euros (about $500,000) in the more developed south.

Maybe our Department of Homeland Security should send staff to Montenegro to seek technical assistance from that nation.

The Book. Two weeks ago I wrote of a recently published book, which I deliberately did not name, that offered easy-to-follow clues to criminal violations of the immigration law that our enforcement agents should read and act upon. I was vague about the location and the nature of these crimes. I wrote that I would identify the book to an enforcement person, but did not want to publish anything further for fear of tipping off the bad guys.

A federal employee said that he was interested, but wanted to ID the book on his own. I gave him an additional obscure clue and he wrote back with the name of the book and its author.

“Was this what you had in mind?” he asked.

“Bingo” was my reply.

This may be the end of the story, or the end of it for a long time, because if an investigation is, in fact, opened, nothing will be said until there is an indictment.

But someone out there is on the case, which is good news.