On Monday the Supreme Court will hear oral argument in a case that has the potential to be the most important in the nation's history. It is no exaggeration to say that United States v. Texas will determine whether America is a nation of laws or whether it has become a banana republic.

This case involves the Deferred Action for Parents of Americans and Lawful Permanent Residents (better known as DAPA) program. This is an expansion of the earlier Deferred Action for Childhood Arrivals (DACA) program. As the names suggest, DACA applies to illegal aliens who came to the country as children and DAPA applies to illegal aliens who have children who are citizens or permanent residents.

Under both of these programs qualified illegal aliens apply and pay a $465 fee. After the government reviews and approves an application (effectively a rubber stamp), the illegal alien becomes "lawfully present" in the United States and receives a work permit.

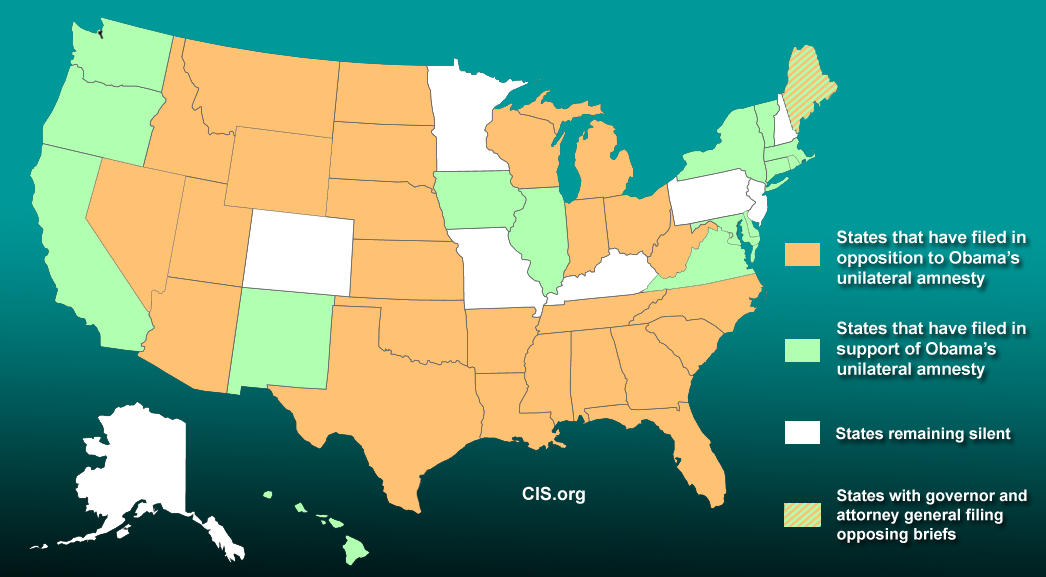

Twenty-six states filed a lawsuit in the United States District Court for the Southern District of Texas to challenge the DAPA program. The states alleged that the DAPA program (1) violates the president's constitutional duty to "take Care that the Laws be faithfully executed"; (2) DAPA was promulgated without public notice and comment; and (3) DAPA is in excess of agency authority.

The outcome of United States v. Texas will determine whether Congress is the constitutional master of the immigration system or whether the president now has shared authority with Congress to create immigration policy through regulation.

Status of the Case

Along with filing the complaint to start the case, the states also filed a motion for a preliminary injunction that the district court granted. A preliminary injunction is a court order to preserve the status quo until the case is resolved. That is, the DAPA program would be put on hold until the case is decided. There are several factors that must be considered before granting a preliminary injunction. However, decision to grant a preliminary injunction is largely at the discretion of the district court.

The government appealed the district court's grant of the preliminary injunction to the 5th Circuit. That court reviewed whether the district court abused its discretion to grant the preliminary injunction. Because this is a preliminary injunction, most of the issues in the case have not yet been decided by the lower courts.

This is why it is odd that the Supreme Court decided to hear this case at all. The Supreme Court normally reviews final judgments. If the Supreme Court is to be a court of law rather than a court of politics, the only thing it would be reviewing in this case is whether the 5th Circuit incorrectly decided that the district court did not abuse its discretion in granting a preliminary injunction.

Nonetheless, it is clear from its petition, opening brief, and reply brief to the Court that the government seeks to have the Supreme Court decide the merits of the case in the context of a preliminary injunction motion. The government's opening brief to the Supreme Court does not argue that the Fifth Circuit did not properly apply the standards for a preliminary injunction. In fact, the government does not mention the rules for granting a preliminary injunction at all. Instead, the government argues the merits of the case before the Supreme Court before those issues have been decided in the lower court. In other words, the government seeks to have the Supreme Court take the political step of inserting itself as the trial court in this case. The cart is now before the horse.

Every outward appearance is that the Supreme Court is on course to take the political route. For example, the Fifth Circuit wrote in its opinion, "We find it unnecessary, at this early stage of the proceedings, to address or decide the challenge based on the Take Care Clause." Yet, the Supreme Court's order granting the government's petition of certiorari states:

In addition to the questions presented by the petition, the parties are directed to brief and argue the following question: "Whether the Guidance violates the Take Care Clause of the Constitution, Art. II, §3."

This suggests that the Supreme Court does not intend to review whether the Fifth Circuit properly reviewed the district court for abuse of discretion, but rather that the Supreme Court wants to take the political step of inserting itself as the trial court.

How the case moves forward depends upon what the Supreme Court does. The easiest next step to predict would be if the states prevail before the Supreme Court. The Supreme Court could find in the states' favor outright or it could DIG (Dismiss as Improvidently Granted) the case, meaning the Court realizes it was a mistake to hear the case at this preliminary stage. Either way, the case would returned to the district court and proceed after a years' delay of the preliminary injunction appeal.

The outcome that makes predicting the future the foggiest is the government prevailing. What would happen next would depend on what the Supreme Court says in its opinion. There are so many possibilities that could flow from that outcome that it is now worth pondering them all.

The Issues

Most media coverage of the case (especially opinion pieces) so far has presented a very warped picture of the case because they do not look at the legal issues. This case presents a number of such issues that, for the remainer of this discussion I break down into four issue categories:

- Do the states have standing to challenge DAPA?

- Is DAPA discretion?

- Is DAPA an interpretive rule?

- Does the Executive have authority to grant DAPA recipients work authorizations?

Some of these issues can be subdivided further, but I stick to a high-level view for this discussion.

The states have to prevail on the first issue (standing). If they lose there, it is all over and the government wins. If the states make it past standing, the government has to prevail on the remaining three issues. A loss on any means the states win.

Standing

Standing is a mechanism for courts to make the political decision whether a party is worthy to bring an action. The Supreme Court has invented standing requirements out of thin air but insists its standing requirements are based in the Constitution and prudential judicial considerations. The rules of standing are conflicted, incoherent, constantly changing, and inconsistently applied. To call standing "law" would imply a level of rigor that simply does not exist.

A full explanation of standing would take an entire book. The basic standing requirement is that the plaintiff must show an injury resulting from the challenged action. That sounds simple and it makes sense that the courts would exclude plaintiffs who do not have a tangible interest in a case, but the question of what is an injury and what causes the injury become the subject of tortured legal hairsplitting. Chief Justice Roberts called standing, "a lawyer's game". A more accurate description would be standing is a complete joke posing as law.

The states pled a number of specific injuries from DAPA. These include having to provide professional licenses, unemployment, and driver's licenses. To have standing only one plaintiff needs to show one injury. The Fifth Circuit held that Texas's cost of providing driver's licenses to DAPA participants was an injury that conferred standing. That sounds simple, but it took the Fifth Circuit 13 book pages of tortured analysis to reach that conclusion.

The counter-argument the government advanced against this injury is that it is self-inflicted. Texas law, attempting to mirror federal law, allows those who are authorized to be present in the United States to get drivers' licenses. If the government allows DAPA recipients to be authorized to be in the United States they become eligible for driver's licenses. As the argument goes, Texas has injured itself by tracking federal law. If only Texas changed its law, there would be no injury.

Except that in another pending case, Arizona DREAM Act Coalition v. Brewer, the government argues that the state of Arizona unlawfully denied DACA recipients driver's licenses. The government says that the Arizona statutes governing driver's license illegality are improper because they do not track federal law. According to the government, if Texas driver's license eligibility tracks federal law, it has no standing and if it does not track federal law the state would be operating illegally.

The dissent in the Fifth Circuit explains what is really going on:

I have serious misgivings about any theory of standing that appears to allow limitless state intrusion into exclusively federal matters — effectively enabling the states, through the courts, to second-guess federal policy decisions — especially when, as here, those decisions involve prosecutorial discretion.

In other words, this judge opines no one should be able to challenge DAPA. This is what the government argues to the Supreme Court as well, that the president can announce a vast program to suspend the law and provide benefits to illegal aliens prohibited by Congress through administrative action without so much as providing the public an opportunity to comment in advance. Hugo Chavez would have been proud.

That illustrates the fundamental problem with standing as it is practiced in the federal courts: Standing provides a defense to any agency action, no matter how unlawful it may be.

The Supreme Court adds to the standing chaos by creating special rules to reach desired political outcomes in specific cases. For example, the Court has relaxed the standing rules bringing an action under the Establishment Clause. In fact, if you want to challenge any kind of religious display there effectively is no standing requirement. One instance of the Court bending the rules to reach a political outcome has bitten back. In Massachusetts v. EPA, several states challenged the denial of a rulemaking petition related to global warming. Those states clearly did not have standing under the rules that existed until that time. However, in that case the Supreme Court expanded standing, holding that the states, as "quasi-sovereign" entities, were "entitled to special solicitude in our standing analysis." Now that opening of the door for Massachusetts to have standing in the global warming context has also opened the door for Texas to have standing in the immigration context — unless the Supreme Court invents yet another new rule.

Many talking heads have argued at length on editorial pages that the states do not have standing to challenge DAPA. The Fifth Circuit gave a 13-page analysis on why the states did have standing. Under the current standing rules, the answer to the question of whether the states have standing boils down to one simple question: Will it be sunny in Central Park six weeks from today?

If the Supreme Court holds that the states do not have standing on the driver's license theory, there is no jurisdiction for the Court to look at the other issues. This creates the possibility that, after the case is remanded, the lower courts could find standing based on some other theory. If the Court finds a lack of standing, it is going to have to come up with some clever way to head off that possibility.

If the Court holds that the states have standing, the government has to prevail on all of the remaining issues to win.

Discretion

Most of the analysis of Texas v. United States has focused on discretion. The government consistently refers to DAPA and DACA as "guidance" in order to play to such analyses. Because so much has been written on this issue (largely to the exclusion of the others), I am just going to state what the issue is. Prosecutors have to use discretion to manage resources in the interests of justice. The question in this case is whether the refusal to prosecute on such a widespread scale, taking of applications and processing fees, and processing applications is really discretion. The Supreme Court has asked the parties whether DAPA violates the Take Care clause of the Constitution ("he shall take Care that the Laws be faithfully executed"). I am treating that question as part of the discretion issue.

Interpretive Rules

Now we get to one of the most mundane legal issues in the case. Under the Administrative Procedure Act, an agency must give public notice and comment before making a rule. However, that requirement does not apply "to interpretative rules, general statements of policy, or rules of agency organization, procedure, or practice." The government refers to DAPA in its filings as "guidance".

There is no question that the government did not provide public notice and comment for DAPA. In order for the government to pass this hurdle, the Supreme Court has to find that the process of collecting fees, processing applications, doing background checks, and granting work permits is merely interpretive.

The government's brief to the Supreme Court is laughable in its in consistency on this point. To argue that DAPA is merely an interpretive rule, it states (p. 66):

[The DACA Directive] explains that "[d]eferred action is a form of prosecutorial discretion" and it "confers no substantive right," "does not confer any form of legal status in this country, much less citizenship," and "may be terminated at any time at the agency's discretion."

And:

A non-qualified alien is not categorically barred, however, from participating in certain federal earned-benefit programs associated with lawfully working in the United States — the Social Security retirement and disability, Medicare, and railroad-worker programs—so long as the alien is "lawfully present in the United States as determined by the [Secretary]." An alien with deferred action is considered "lawfully present" for these purposes.

So DACA makes aliens "lawfully present", but does not confer "any form of legal status in this country", and DACA "confers no substantive right", but makes aliens eligible for "Social Security retirement and disability, Medicare, and railroad-worker programs." Up is down, left is right, and day is night.

Work Permits

The final hurdle for DAPA is its work permits. The government calls DAPA "guidance" and "prosecutorial discretion". Prosecutorial discretion is the choice not to do something (prosecute), but the DAPA program affirmatively gives illegal aliens the ability to work in the country. This is particularly problematic because Congress has expressly prohibited illegal alien employment.

The solicitor general relies on crafty cut-and-paste for this issue. He argues:

The connection between enforcement discretion and work authorization is close and natural: Exercising discretion means that aliens will live in the United States, and "in ordinary cases [people] cannot live where they cannot work." (pp. 18–19).

Here DHS is quoting an earlier opinion from the Supreme Court, Truax v. Raich. But this how the passage in Truax reads without cut and paste.

The assertion of an authority to deny to aliens the opportunity of earning a livelihood when lawfully admitted to the State would be tantamount to the assertion of the right to deny them entrance and abode, for in ordinary cases they cannot live where they cannot work.

Obviously, the illegal aliens in the DAPA and DACA programs were not "lawfully admitted".

This is a disturbing sign from the solicitor general. He knows full well that the clerks for the Supreme Court are going to catch this blatant misrepresentation. Doing it anyway suggests that the Solicitor General believes that presenting misleading information to the Court will not matter to at least certain judges.

Several of the amicus briefs allude to the solicitor general's strategy here, making the historical reference to the restoration of the Stuart kings of England.

The amicus brief of Governor Abbott, et al. says:

Charles I's hand-picked judges ruled 7–5 against Hampden and held that (1) the king had absolute power to defend the nation, and (2) where Parliament fails to act, the king can (or must) act unilaterally.

Sounds familiar. Let us hope that our Supreme Court has not been similarly corrupted.

In fact, United States v. Texas has brought to a head a larger issue. For years previous administrations had been allowing aliens to work in situations when they had no authority to do so. What is new under President Obama is that the administration now explicitly claims that it has unlimited authority to allow any alien to work — unless Congress explicitly prohibits it. Except that even when Congress explicitly prohibits such work (as in illegal aliens) the president still claims authority to grant it. Obama also claims authority to make any alien "lawfully present" in the United States. In other words, Obama claims to have the power to allow any alien to be in and work in the United States.

This flips the Constitution on its head. Up until now, the Supreme Court has repeatedly held that Congress has plenary power over immigration: "Over no conceivable subject is the legislative power of Congress more complete than it is over the admission of aliens." The Supreme Court will determine if Congress still makes the laws or whether the living, breathing Constitution has given rise to the new chief executive office of Caesar.