In what was, to me, a surprising decision (given its source), a three-judge panel of the federal Ninth Ciruit Court of Appeals has overruled a district court judge who had enjoined the Department of Homeland Security (DHS) from terminating Temporary Protected Status (TPS) for individuals from a variety of countries — El Salvador, Haiti, Sudan, and Nicaragua — based on the "racial animus" of the president.

How many aliens will actually be affected depends on which news source you review. Some have said 300,000; others use the figure 400,000, which is quite a disparity. And, of course, the spin in the article you read generally follows the slant of the media source, a sad commentary on the state of independent journalism today.

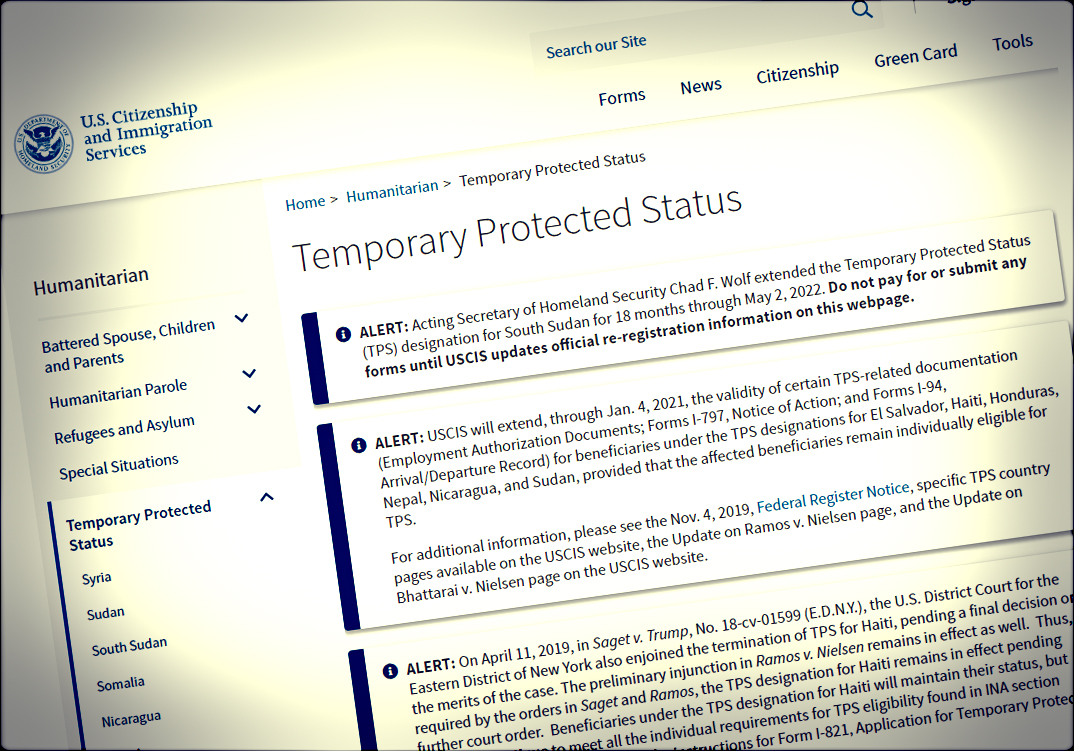

The panel's decision was a sharp-tongued rebuke of the judge and equally tart in finding that there had been no basis for entertaining the complaint of the plaintiffs in the first place since it was not grounded in law. Certainly the intent of the TPS statute (found at Section 244 of the Immigration and Nationality Act (INA), and codified at 8 U.S.C. Sec. 1254a) seems clear enough: to provide a temporary safe haven to aliens who don't qualify for asylum or refugee status or other forms of relief, when acts of God or civil conflict render going home untenable for a period of time. However, as the law makes clear, when the basis for the grant of TPS is no longer there, the status is to be ended and aliens thereafter expected resume their nonimmigrant status, or depart if they were illegally in the United States when granted TPS.

The problem is that, in the case of these nationals, past administrations exercised not-so-benign neglect and simply allowed TPS to continue on autopilot, renewing it year after year, leading in the end to a sense of entitlement on the part of the hundreds of thousands of recipients — many, perhaps most, of whom were never in the United States legally and who by any reasonable measure ought to have been told that their time was up long ago.

Of course, the slow grind of the federal court system virtually guarantees that the fat lady has not yet sung. Next will likely be a motion to have the full circuit court reconsider the case, in which instance the pedigree of the jurists may alter the outcome (two of the three-judge panel were appointed by Republicans and one was a Democratic appointment, whereas the full circuit remains overwhelmingly liberal). And whether or not the matter is actually heard by the full circuit, it takes little imagination to expect the Supremes to ultimately be asked to sing the tune that will, at least theoretically, render a final outcome.

But the stakes are high and the fundamental question is grave: Is a president forever and always obliged to hew to the course (and live by the mistakes) of his predecessors? While the instant matter may involve immigration, that's really what's at stake. This, too, was the heart of the DACA controversy that the highest court so recently flubbed.

Ask yourself this: If one president sends troops to war in some far-off, forgotten land where we begin to doubt that our national security is truly at stake, must all presidents honor that call and keep our forces there in perpetuity? How about drone strikes that kill U.S. citizens without even a pretense of due process in making the decision? If one president does so, should all who follow accept that judgment?

Think up your own scenario; there are dozens immediately at hand. Is that what precedent and jurisprudence require? Unlikely, isn't it? So why carve out exceptions in the realm of immigration that are so obviously at variance with both the intent and plain language of the law?