The U.S. southern border remains vulnerable to potential terrorist transit, although terrorist groups likely seek other means of trying to enter the United States.

— U.S. Department of State "Country Reports on Terrorism 2017", released September 2018.

As explained already at some length in my recent CIS Backgrounder, migrants from Muslim-majority countries routinely get to the U.S. Southwest border by first reaching Latin America and traveling smuggling routes northward. Human smuggling networks that move these so-called "special interest aliens" through Latin America pose a recognized vulnerability of terrorist infiltration, which has driven significant American homeland security efforts to degrade them. These efforts are chiefly led by ICE Homeland Security Investigations stationed throughout Latin America.

To those of us who pay attention to related policy and operational matters, one important source of unclassified information can always be counted on to refresh analytical thinking. It comes from the U.S. State Department's annual "Country Reports on Terrorism" by the agency's Bureau of Counterterrorism. The latest report, reflecting calendar year 2017, was just released this month. All 340 pages of it can be read here.

Or, for quicker learning about how the report might inform this illegal migration threat issue, you can read highlights I picked out below.

First, a quick word of background and context: Each year, under requirements of the 2004 Intelligence Reform and Terrorism Prevention Act, the State Department has to provide Congress with a "full and complete annual report on terrorism for those countries and groups meeting the criteria of the Act." Typically, the report focuses on how nations where extremist groups operate are countering their respective (often unique) terrorism problems in Africa, East Asia and Pacific, Europe, the Middle East, North Africa, and South and Central Asia.

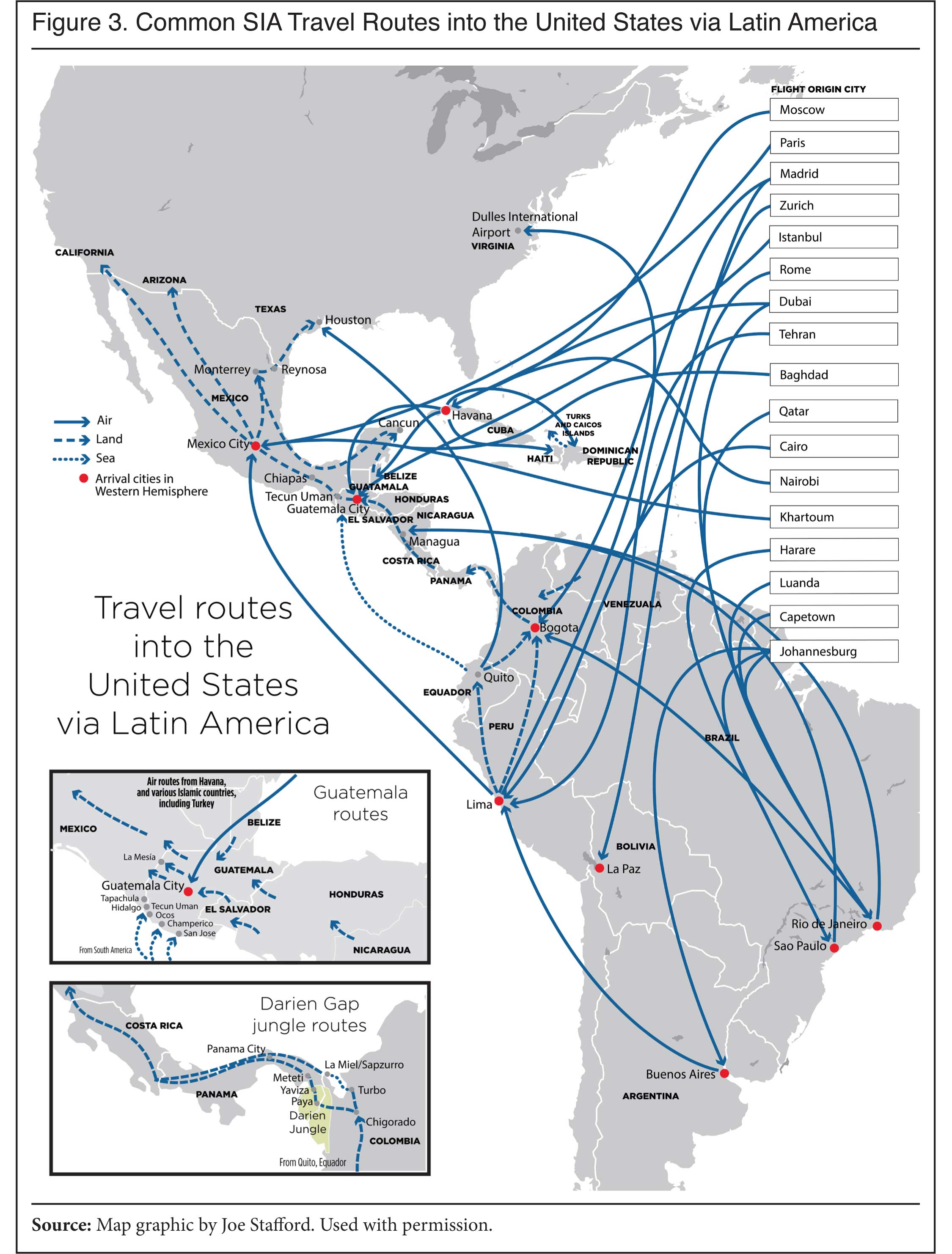

And the report includes, of course, the "Western Hemisphere" sans the United States. This section often provides telling new details about porosity and localized immigration enforcement initiatives that impact assessments about the border infiltration threat. The map below reflects data I've culled from two dozen U.S. court prosecutions of SIA smugglers over the years demonstrating where in Latin America special interest aliens are transported on their way north.

The State Department report, threading the issue with diplomatically aware language, provides an overarching assessment of how Latin American countries are doing in the immigration area.

First the bad news: "Many Latin American countries have porous borders, limited law enforcement capabilities, and established smuggling routes. These vulnerabilities offer opportunities to foreign terrorist groups."

And some good news: "[B]ut there have been no cases of terrorist groups exploiting these gaps to move operations through the region."

While it may be true that organized, hierarchically arranged "terrorist groups" didn't systematically deploy along the routes as ISIS did in Europe, the report unfortunately does not address whether unaffiliated small cells or home-grown individuals did, as also occurred in Europe. Quite a few home-grown citizens of Latin America have radicalized and plotted local attacks, even if it is not known that any wanted to head north to America on the smuggling routes. Hezbollah presences cropped up quite a lot in the reporting, too. For example, the report mentions, among many such instances, that Bolivian security services uncovered a Hezbollah cache of explosive precursors in the La Paz area.

The following summaries are based on excerpts about countries that some of my past research showed were most often used for the staging and transit of special interest aliens. (Not all of the countries you see on the map are reflected in the State Department report, and I added Trinidad & Tobago).

Argentina and Paraguay

The free trade zones in the Tri-Border Area of Argentina, Brazil, and Paraguay remained "regional nodes for money laundering" and where "suspected terrorism financing networks operate." The report states that Argentina and Paraguay, together with Brazil, attempt to coordinate law enforcement efforts there via a "Trilateral Tri-Border Area Command."

In Argentina during 2017, the government consolidated plans to redefine its counterterrorism strategy with a focus on these nodes on its remote northern and northeastern borders. What that may mean in operational terms is mostly left unsaid. For instance, although my research shows that special interest alien smugglers most certainly have flown into Argentina to use it as a staging and transit country, the State Department report offers no word on whether the Tri-Border Area plays any role or whether the tri-country command has concerned itself with this issue. The report did say that "robust U.S.-Argentine law enforcement and security cooperation continued during 2017." For example, the government improved its capacity to use the Advance Passenger Information system to identify suspected terrorists trying to fly into Argentina on commercial carriers. Something like that might deter SIA smugglers from flying suspect clients in there.

The government created a new law enforcement task force to focus generally on Tri-Border Area "criminal activity and terrorist incidents". With help from CBP, the Argentines deployed more tech and people to "high-risk ports of entry" along the country's northern border. The government also started using biometrics in its security vetting processes to detect suspected terrorists from "exploiting its immigration system."

In Paraguay, the government seemed more interested in its ongoing crackdown on a local separatist group known as the Paraguayan People's Army, or EPP, than on controlling its borders. The report stated that ineffective immigration, customs, and law enforcement controls in Paraguay left borders largely uncontrolled. None of which inspires confidence knowing that, with U.S. help, Paraguayan law enforcement arrested multiple Lebanese Hezbollah-linked suspects in the area for money laundering and drug trafficking, Again, the report omits whether such operatives were even interested in smuggling themselves or others from or through Paraguay. But border security in Paraguay, the report stated, "suffered from a lack of interagency cooperation ... as well as pervasive corruption within security, border control, and judicial institutions."

Brazil

Brazil shares vast international borders with 10 countries, and many of its borders remained porous and largely unpatrolled. "Irregular migration, with Brazil often serving as a transit country, is a problem, especially by aliens that raise terrorist concerns from areas with a potential nexus to terrorism."

Brazil increased its focus on border security in 2017 as part of an overall National Public Security Plan, with multiple Brazilian state and federal agencies agreeing to come up with some ideas to improve on tackling such a monumental security challenge. A new immigration law did take effect in November 2017 by which to detain and deport illegal migrants, "but aside from reaffirming the importance of border security it did not have a specific terrorism focus."

Brazil and the United States did make some progress toward countering document fraud, with joint operations disrupting "a number of document vendors and facilitators, as well as related human-smuggling networks." The United States provided fraudulent document recognition training to Brazilian airline and border police units. And the Brazilian Army started deploying a system of personnel, cameras, sensors and satellites along some of the country's borders "with [the] intention to cover the entire Brazilian border by 2021."

Before the 2016 Olympic games in Brazil, police arrested 10 people suspected of belonging to a local ISIS cell and plotting to attack the Rio Olympics. In 2017, Brazil arrested 11 more people on charges that they planned to establish an ISIS cell, though no information has surfaced that any of them planned to travel to the United States.

Colombia

Colombia remained a transit point for the smuggling of third-country nationals seeking to reach the United States illegally. These no doubt found it helpful that, "Colombian border security remained an area of vulnerability," and that "Law enforcement officers faced the challenge of working in areas with porous borders and difficult topography plagued by the presence of illegal armed groups and drug trafficking."

The report goes on to explain that the Colombian National Police "lacked the personnel to enforce uniform policies for vehicle or passenger inspections at land crossings." So no one is watching even many of the established border crossings, just working pretty much airports.

Biometric and biographic screening was conducted only at international airports. The Colombian government uses Advance Passenger Information, but "does not collect Passenger Name Record data. Of its 184,000 officers, the CNP has 2,202 working on customs enforcement activities."

To boot, the economic crisis in Venezuela had swamped whatever capacity the CNP had left with 660,000 Venezuelan refugees, about half of whom entered Colombia illegally. "There were no significant changes since 2016 in cooperation on border security, evidence sharing, and joint law enforcement operations with neighboring countries."

Peru

The border crossings in and out of Peru remained fairly laissez-faire, despite the country's confirmed position as a special interest alien transit country and some internal prosecution activity for Islamic terrorism. On border security, immigration authorities collected limited biometrics information from visitors. Citizens of South American countries were allowed to travel to Peru by land using only national identification cards. There was no visa requirement for citizens of most countries from Europe, Southeast Asia, and Central America (except El Salvador and Nicaragua).

The Peruvian government's prosecution of a Lebanese citizen with links to Hezbollah arrested in 2015 — after discovery of residue of explosives in his apartment — was still ongoing in 2018, with the Peruvians successfully appealing a ruling acquitting the operative of terrorism charges.

Panama

A lot of progress can be reported regarding special interest alien travel through Panama this year and the country's "counterterrorism efforts" with the United States. One of the more significant, new bits of information from the report is that Panama and the United States have been working "to detain and repatriate individuals for whom there were elevated suspicions of links to terrorism."

Prior to this, I'm not sure it was publicly reported that Panama was repatriating terrorism suspects caught along the smuggling routes to their home countries. Not only that, the report strongly suggests that the U.S. Department of Homeland Security is working with Panama to collect biometric data for the U.S. government's Biometric Identification Transnational Migration Alert program "to enhance risk-based traveler screening and migration and criminal databases." That means someone's collecting eye scans, fingerprints, and DNA from migrants apprehended in Panama. This is all very good news even if these programs cover only a fraction of those moving through Panama every year.

In 2017, more than 8,000 migrants entered Panama illegally through its airports, sea ports, and by foot through the Darien Gap connecting South America to Central America (see map), according to the report. I think it's doubtful all 8,000 underwent enhanced screening or provided their biometrics, not knowing how many DHS personnel are down there working this issue and especially when many migrants likely arrived with no documentation, or fraudulent identification. One obvious value is that the collection of biometrics associated with a migrant name in Panama means that homeland security personnel can later more easily detect when the same migrant offers a different name further up the trail.

Still, the Darien Gap remained a problem as smugglers continued to use old Revolutionary Armed Forces of Colombia (FARC) jungle routes "for illicit transit of travelers that raise terrorist concerns."

Meanwhile, Panama has been conducting "targeted operations" with Colombia and Costa Rica to degrade illicit migration. That's new as well. And so is this: U.S. Customs and Border Protection teams, along with teams from Mexico, partnered with Panama at the country's Tocumen International Airport to identify air passengers "linked to terrorism", among other undesireables.

Lastly, Panama cooperated with U.S. law enforcement on various counterterrorism cases, including individuals linked to the terrorist group Hezbollah. The report noted that a Hezbollah operative arrested in the United States in June 2017 allegedly was involved in surveilling U.S. and Israeli targets in Panama.

Mexico

One of the more interesting conclusions of the State Department report, is this definitive statement: "At year's end, there was no credible evidence indicating that international terrorist groups have established bases in Mexico, worked with Mexican drug cartels, or sent operatives via Mexico into the United States." Again, this assessment limits itself to "international terrorist groups" organizing deployments, rather than small, unaffiliated, independent cells and individuals.

The report stated that "The U.S. southern border remains vulnerable to potential terrorist transit", but attenuates this assessment by adding that, while this may well be true: "terrorist groups likely [will] seek other means of trying to enter the United States."

Counterterrorism cooperation between Mexico and the United States was assessed as "strong" during 2017 and "Improved information sharing regarding migrant populations constituted a major step forward." The two governments collaborated to improve airport security at last-departure point airports to the United States. The United States helped Mexico create an information-sharing system for Mexico that will "vastly improve Mexico's ability to partner with U.S. law enforcement to prevent terrorism."

Persistent listed "challenges" come as no surprise: lack of professionalism, corruption, and insufficient inter-agency communication on border security.

Trinidad and Tobago

These Caribbean islands are included here because this small country has a jihad problem, and it's easy to travel to there from, say Syria, and from there to the special-interest smuggling lanes of South America.

The U.S. government in recent years has really pushed the island nation to do counterterrorism, in part because about 135 radicalized islanders have traveled or attempted to travel to fight with ISIS.

"The threat from the possible return of foreign terrorist fighters remains a primary concern," the report states.

Six Trinidadian individuals or entities are on an international sanctions list for terrorism involvement.

For the first time, in November 2017, the Trinidad and Tobago National Security Council approved a national counterterrorism strategy and has shared intelligence with the United States. The report doesn't talk much about security effectiveness at its sea and air ports. But in April 2017, the country agreed to install the Personal Identification Secure Comparison and Evaluation System (PISCES) at certain points of entry to the islands. The biometrics-based system is used to detect when in-bound watch-listed or wanted terrorist suspects board a flight or appear at a border.

Venezuela

Also a fairly frequent point of transit on the special interest aliens smuggling route, Venezuela has long proven intransigent when it comes to cooperating with the United States on that national security issue or any other:

In May 2017, for the twelfth consecutive year, the U.S. Department of State determined … that Venezuela was not cooperating fully with U.S. counterterrorism efforts. The country's porous borders offered a permissive environment to known terrorist groups. … Border security at ports of entry was vulnerable and susceptible to corruption. The Venezuelan government routinely did not perform biographic or biometric screening at ports of entry or exit. There was no automated system to collect advance Passenger Name Record data on commercial flights or to cross-check flight manifests with passenger disembarkation data."

Enough said.