PIEDRAS NEGRAS, Mexico, February 18, 2019 — Inside the sprawling ceramics factory where the Mexican government has detained the latest migrant caravan, a process is underway virtually guaranteeing that almost everyone here will soon be granted exactly what they came for: an opportunity to breach the U.S. southern border, exploit the American catch-and-release loophole by claiming asylum, and add themselves to the millions already living in the country illegally.

This caravan of some 2,000 mostly Hondurans, with a smattering of Salvadorans and Guatemalans, began arriving on February 8, but was unable to rush the American border en masse because the Mexican government detained them all first in the Piedras Negras ceramics factory, surrounding it with troops and state and local police forces. Preventing a mass swim across the Rio Grande, that would have been covered by international media, may have improved political optics for both the Mexicans and the Americans, and the state of Coahuila announced that it will close the improvised shelter sometime this week after several riots and disturbances by those demanding release to the U.S. border.

However, the process that will enable Mexico to accomplish such a quick shelter closure portends an unseen, very different outcome than the one intended by U.S. administration officials and current immigration policy. The process also portends precisely the outcome sought by everyone in this caravan and in any future ones. Under the auspices of a special visa program, Mexico is essentially dispersing the migrants around northern Mexico where they will be free to try their luck crossing other parts of the American southern border and to then access the much-prized American catch-and-release loophole they have always sought, though in smaller, less visible-groups.

In one section of the Piedras Negras camp last Thursday, CIS observed hundreds of migrants waiting in line to apply for special Mexican work visas of a year duration. At the same time, in another area of the camp, hundreds more migrants with those visas freshly in hand gathered as Mexican immigration officials called out the names of the 100-applicant groups that will be put on at least one waiting bus to some other Mexican city, such as Monterrey or Hermosillo, ostensibly to live and work for the year. And in a third area is the line to board the big, sleek bus parked inside the factory with a hand-written sign on the door that reads: "Salida Monterrey".

It is through this process that the caravan population is being inexorably reduced each day and dispersed in small groups to other parts of northern Mexico.

But Mexican officials in the camp, as well as migrants taking part, acknowledge that no enforceable legal provision can possibly prevent anyone stepping off these buses in destination cities from immediately turning north toward the U.S. border, where they can access the much-desired catch-and-release loophole with a claim of asylum to any American uniformed officer. All any migrant need do to live in the United States for years after a border crossing is request asylum for which most Central Americans are not eligible, receive a distant hearing date to confirm that ineligibility, and be freed into the country indefinitely for lack of detention facility space.

To those familiar with often-arcane immigration systems, this ultimate outcome of the caravan-dispersal process CIS witnessed at the Piedras Negras camp is not difficult to fathom.

"They're all going to ultimately cross, just in a different location than here," said Agent Jon Anfinsen, local president of the Border Patrol Union in Del Rio, Texas, which covers Eagle Pass (the Texas town opposite Piedras Negras). "This has to do with them [the Mexican government] showing they're trying to do something. What this does is make everything more digestible for both sides. It's more orderly, but it's not stopping it [illegal crossings into the U.S. by caravaners]."

While it may be too early to quantify how many freshly transported visa-holding Piedras Negras caravan riders actually resumed their quest for the border crossing, ample anecdotal reporting supports the notion that Central American migrants in previous caravans used their Mexican visas for just that. For example, the Washington Post reported in January that 10,000 Central American migrants had requested special Mexican humanitarian visas that would allow recipients to legally cross Mexico's southern border and to then, ostensibly, stay to work local jobs. (Mexico reportedly rescinded the visa program in January.)

But the Post said Mexican officials acknowledged that while Mexico offered jobs under the temporary work permits, "the vast majority of the migrants want to head to the United States."

Likewise, a Los Angeles Times story about the Mexican visa program reported: "Although some applicants say they may consider remaining in Mexico, many acknowledge that their ultimate aim is to enter the United States and apply for political asylum." Which, as mentioned, provides for release into the interior pending distant court hearings that the vast majority either skip or lose and then easily evade the prospect of deportation indefinitely.

In November, the first major caravan from Central America reached Tijuana at approximately 6,000 strong. The Mexican government helped block the multitudes from rushing uniformed American officials, but about 2,600 made it over the border, according to the Associated Press. Mexico issued humanitarian work visas to 2,900 others.

Although the AP report declared that many "are now working legally there with visas," not long after those 2,900 visas were issued, groups of 100-300 suddenly began turning up at border zones unaccustomed to such traffic. For example, U.S. Customs and Border Protection reported this month that 28 different groups of more than 100 Central Americans have been apprehended at the remote Antelope Wells port of entry 122 miles west of El Paso, Texas.

That happens to add up to about the 2,900 humanitarian work visas issued to the Tijuana caravan members.

It's unconfirmed whether these busload-sized groups in the El Paso sector were from the Tijuana caravan, of course, or whether any of them were ever asked if they had Mexican work visas.

In Piedras Negras, meanwhile, an English-speaking migrant who gave his name as Alex Torres and refused to have his photo taken, said he was deported from Indiana, where he had been living since he was a child, back to his native El Salvador. He wouldn't say why he was deported, but U.S. immigration authorities typically prioritize criminal aliens for such deportations.

Despite his deportation, Torres said he joined the caravan because he was determined to return to the United States and the caravan provided an easy means to do so.

Pressed as to whether he would try re-entering the United States once he had his visa and was bused to some other Mexican city, Torres suddenly became careful. He said he'd probably try to find work at a fancy Acapulco hotel.

"The United States ain't playing games anymore," when it comes to hunting down and deporting illegal aliens, he said.

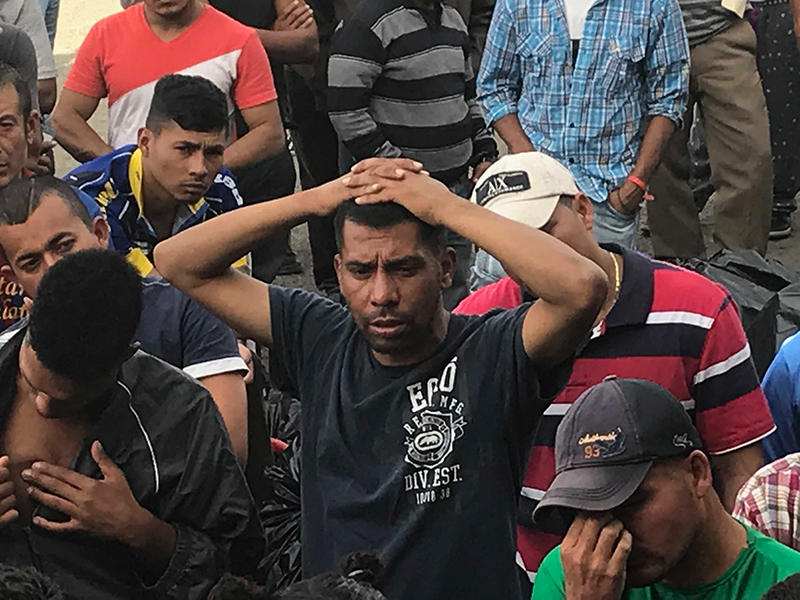

What the Piedras Negras caravan members have made abundantly clear through action, with several riots and at least one deliberate arson, is that they want out so that they can get to the U.S. border immediately.

The disturbances — and the media attention they brought — also unnerved Mexican officials and may have been a factor in the decision to bolster security with riot police and to quickly close the shelter.

Jose Angel Hinojosa, a Piedras Negras city council member overseeing some operations at the shelter, told CIS that about 25 hardened gang members from Honduras and others who were flagged in law enforcement database systems were identified as responsible for instigating the disturbances and removed last week. The disturbances drew riot police and bloodied several migrants. In one disturbance the migrants burned several mattresses, demanding they be freed to finish their journeys to the American border only a few miles north.

Along those lines, some of the migrants complained to human rights advocates about inhumane conditions inside the shelter. However, Torrez, the deported migrant, said none of that was ever true.

"People are saying this is like jail, but not really, 'cause they given us everything," he said.

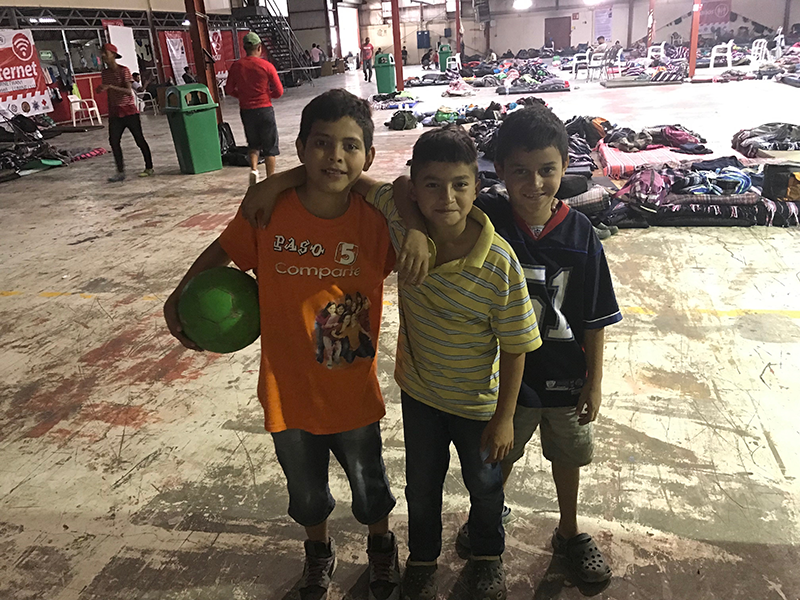

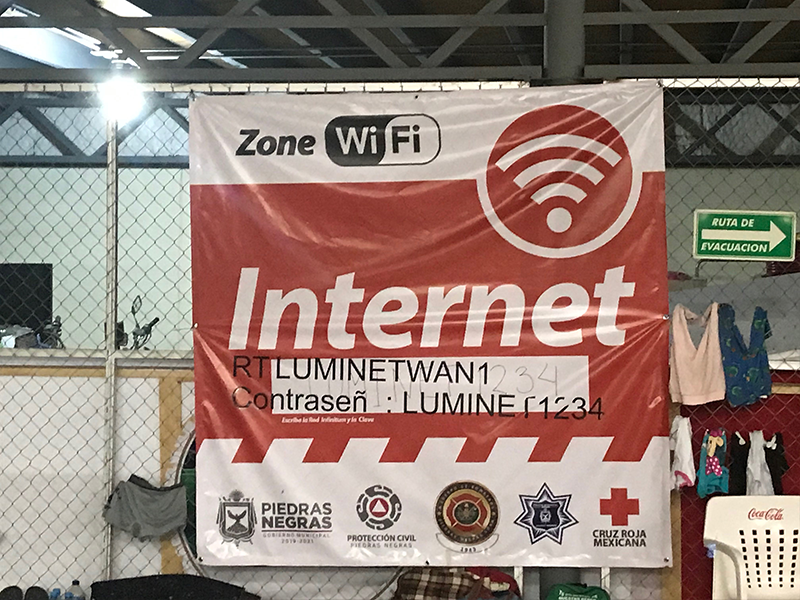

Indeed, a tour Thursday showed that Mexican officials had provided food, medical treatment, big screen televisions showing Netflix movies, access to plentiful personal hygiene supplies, internet access, regularly cleaned shower areas and portable toilet facilities, as well as access to doctors and dentists. Young children had soccer balls and space to play the game. Teenagers had areas for music and dancing. A number of entrepreneurs ran small table-top convenience stores selling food items.

For public relations, Mexico appears to be doing the Americans a big favor by stopping and detaining the thousands of Central Americans arriving in caravans. But the reality is that Mexico is simply breaking up the caravan into small amorphous groups of migrants who in all likelihood will, just a little bit later, make their ways separately to other parts of the U.S. border, where they'll all eventually cross without a "caravan" identity.

Meanwhile, as Mexico closes its shelter and is thanked for its helpful cooperation, one thing is for certain: Anyone in the caravan who wants to cross the U.S. border will almost certainly do so very soon.