WASHINGTON, DC – The leader of the Embera Tribe left his jungle homeland in Panama’s Darien Gap and came to the nation’s capital last week with an SOS message to the American people: a record-setting mass migration through his reservation, spurred by President Joe Biden as soon as he entered office this year, is destroying the tribe’s traditional ways of life at a pace beyond living memory and corrupting its people to an entirely unacknowledged extent.

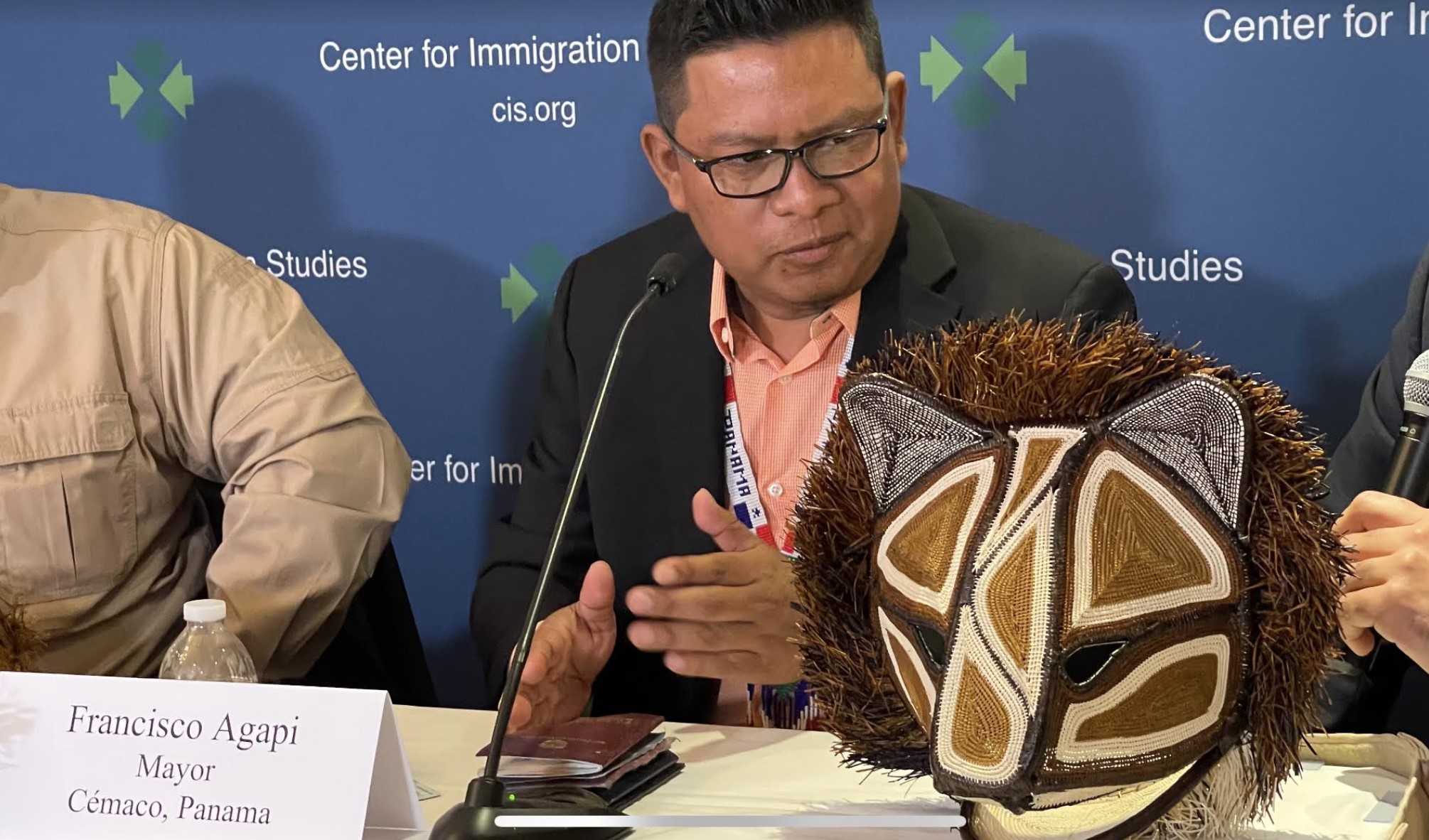

Mayor Francisco Agapi, who heads 29 villages in and around the isolated Embera tribal capital of Bajo Chaquito, spoke publicly for the first time of his tribe’s plight on December 7 while serving on a panel about the Darien Gap migrant passage hosted by the Center for Immigration Studies, which sponsored his travel from Panama.

Some 35,000 of the agrarian Embera live largely from jungle rivers along the Panama-Colombia border, right where the Darien Gap migrant pathways have emptied a record estimated 100,000 migrants from more than 100 nations (10 times the usual annual numbers) on their way to the U.S. southern border, a great many drawn by word of lenient Biden administration policies that show no sign of lifting in its remaining three years.

During the panel and later to several Republican members of Congress, Mayor Agapi expressed puzzlement as to why human rights groups that protect indigenous tribes – and a Panamanian government interested only in moving them into the next country – have forsaken his tribe’s new problems in favor of facilitating the historic migrant tide he believes is causing them. Front and center among these is a food insecurity crisis that developed in 2021. The Embera leader said not a single advocacy group for indigenous peoples has reached out to assess how the tribe is managing the 2021 migrant swell through its territory.

“One of the rights that we’re fighting for – human rights – is just our sustenance, because a lot of these immigrants are passing through our fields. They take a lot of our crop, so a lot of folks are without food, without crops,” Mayor Agapi explained as one ill effect of the mass migration swamping his tribe. “And we’re the only ones that are fighting for this. There are no other organizations that are recognizing that this is a problem and fighting for us.

“There are no organizations that are fighting for our human rights.”

Food insecurity has spiked not just because thousands of hungry migrants are taking the harvests. With so much easy money coming in for transporting and guiding the migrants, many Embera men have abandoned their duties to plant new crops for these new endeavors, or to hunt and fish.

“Especially in the last few months, it’s been a terrible problem for us.”

Of primary concern to Mayor Agapi is the corrupting influence of cash the migrants offer the Embera for guiding and transportation services, previously unimaginable sudden relative wealth that most young people are ill-equipped to manage.

“The problem is that, honestly, the immigrants bring money with them,” he said. “That’s the source of the problems.”

This year, the money fueled a rash of alcoholism and cocaine use among Embera youth. A typical fee for a ride aboard a motorized Embera canoe is $25 per migrant. Hundreds of such boats move constantly along rivers from to ferry migrants fresh out of the Gap into Embera villages and eventually into Panamanian government hands. The Panamanian government, which sees a national interest in ensuring the migrants keep moving to the next country, maintains hospitality camps near the Pan-American Highway and facilitates bus transport on it north to Costa Rica, as CIS was first to report in late 2018.

With this year’s shift to modern money, he said, the tribe’s youth are spending proceeds on cocaine and alcohol, becoming addicted and tearing families apart. Some are leaving the community for extended periods to use drugs in Panama City and transport them back to the jungle for sale to others.

“The first problem is alcohol, especially in our younger generation. So when they become alcoholics, then it becomes a family problem between married couples,” he explained.

Mayor Agapi said the Panamanian government is entirely indifferent to the tribe’s sufferings, showing only overriding interest in helping the migrants who are causing them.

In a moment of somewhat pained candor, Mayor Agapi did describe another problem besetting the tribe that has drawn government attention: some Embera men are using hunting rifles passed down from father to son for generations to rob and rape the migrants in the jungle.

During his Washington trip last week, the Embera leader said he was traveling among the villages to warn men to stop these terrible abuses. But he also acknowledged that he had little power to do much more than persuade his people that such crime is not part of Embera culture and to work with police.

Out of that, though, he said another injustice for the tribe is emerging, Mayor Agapi said, one that also has gone unnoticed by human rights groups that might rush to aid any other indigenous tribe.

Panamanian police have begun charging his tribe’s elderly with serious crimes – “the grandfather, the grandmother, the older folks” – because the hunting firearms used in the crimes were originally registered in their names before they passed them down to the younger generation for hunting wild game.

“So when I have to present myself in front of the prosecution, they’re accusing me that I am essentially like the godfather of this operation and I am renting these weapons out,” the mayor said.

In his plea for some protection from the migrant onslaught and any acknowledgement of it at all, Mayor Agapi described a diversity of other social and cultural ills it has brought on this year.

With thousands of migrants a week showing up in Embera villages after long foot journeys through the Darien Gap, they relieve themselves for days at a time everywhere and especially in the river, which provide the main source of water. The migrants have taken over family huts and filled village school buildings to the point that “our kids can’t even concentrate on education because we are overwhelmed with so many immigrants,” Mayor Agapi said.

Mayor Agapi wants the governments of Panama and Colombia to do something – anything – to dramatically reduce the migration and for human rights organizations that specialize in protecting indigenous tribes to intervene on behalf of Panama’s Embera, rather than support the mass migration that is damaging his people.

During the covid pandemic, those governments unwittingly demonstrated that they could indeed dramatically reduce this traffic. Governments from Colombia to the United States closed their borders and only occasionally let groups through to relieve problematic buildups. In February, Colombia and Panama reopened the borders, and with new Biden administration policies opening the American border to passage by many, the flood of humanity has only increased.

Agapi understands why Panama did not want the migrants pooling up in the country and that they just be moved on. The migrants burned down half of one of his villages during a rampage.

Asked if he had any message for American policymakers in Washington who seem largely indifferent about the Darien Gap’s role in the border crisis, Mayor Agapi responded:

“My message is please pay attention. This is a joint effort. This is a problem for everybody and all the organizations that are involved, to include the politicians here. You can help us, at least a small bottle of water for my people.”