In my last post, I discussed two amnesty bills that will be considered this week in the House of Representatives: H.R. 6 (the "American Dream and Promise Act") and H.R. 1603 (the Farm Modernization Workforce Act). Deep down in H.R. 6, in paragraph 102(c)(3) of the "Dream Act of 2021", is a curious provision that allows the secretary of DHS (and only the secretary) to provisionally deny an application for benefits. It contains some curious provisions that make no logical sense.

Briefly, that portion of H.R. 6 would allow aliens to obtain conditional green cards if they are illegally present in the United States, have Temporary Protected Status (TPS), Deferred Enforced Departure (DED), or are the children of certain nonimmigrants, provided that they entered the United States under the age of 18 on or before January 1, 2021.

There are also special rules in H.R. 6 for aliens who have been granted Deferred Action for Childhood Arrivals (DACA) to obtain permanent residence.

There are requirements (not terribly stringent) that applicants must meet for those benefits, bars thereto, waivers for many of those bars, and exceptions to those waivers. Most of the adjudications for applications under the Dream Act of 2021 would logically be done by line adjudicators at USCIS.

Paragraph 102(c)(3), however, is an outlier, because it provides for a secondary review and provisional denial by the DHS secretary. As noted, the secretary cannot delegate the authority for that review, pursuant to subparagraph 101(c)(3)(A).

Consider that for a moment. There are more than 240,000 employees at DHS, and the secretary is legally responsible for all of them. DHS's components run the gamut from TSA to cybersecurity to the Coast Guard. And in the midst of all of that, the secretary is expected to make decisions about cases involving individual aliens.

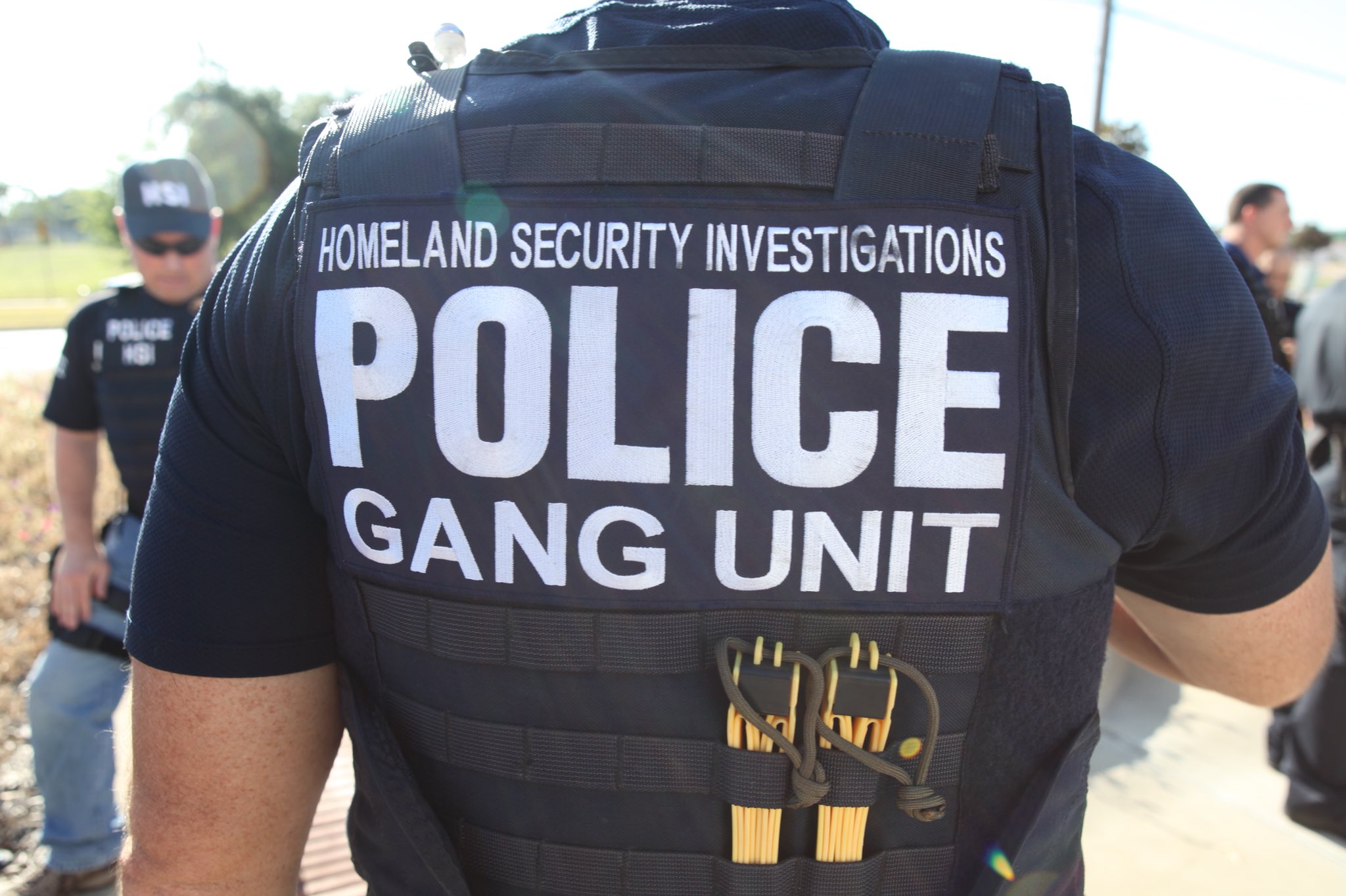

But it gets stranger yet. That secondary review covers deniability on just two grounds: public safety and gang participation.

The public safety ground is linked to, and dependent upon, the alien's criminal history. The gang-participation ground is itself subject to any number of caveats, and the basis for a denial on this ground is quite restrictive. Let me put it this way — there are a number of known public safety risks and gang members whom the secretary in his discretion cannot deny.

It does not end there. The secretary of DHS — in charge of almost a quarter-million employees — cannot simply deny an applicant under the Dream Act of 2021 just because he determines that a criminal alien (most likely illegally present to begin with) is a public-safety risk or a gang member.

The secretary must send that alien written notice by certified mail and e-mail (if any, copied to the alien's lawyer, if any) "articulat[ing] with specificity all grounds for" the secretary's preliminary determination, to include "the evidence relied upon to support" that determination.

Then, the alien (again, more likely than not here illegally whom a cabinet-level official has determined is a significant threat to public safety or a gang member under some fairly restrictive criteria) has 90 days to respond. Lest that individual fail to realize the magnitude of a certified letter from the secretary of DHS, the secretary has to send the same letter within 30 days of sending the first (again, with an e-mail, assuming the alien has an e-mail address, copied to the alien's lawyer, if the alien has one).

If, after clearing all of these hurdles, the secretary provisionally denies that application, the process gets even weirder. Because the alien can then go within 60 days to the local federal district court and have that denial reviewed de novo, that is with the judge giving no weight whatsoever to the decision of the secretary of DHS.

Most district court judges are exceptional lawyers, and experts in some field of law. It is not clear, however, why anyone would think that any given one of them should be able to second-guess a cabinet official. And DHS has to rest on the record that the secretary has created, while the alien can introduce any additional evidence he or she wants.

Did I mention the part about appointed counsel? Even if the alien already has a lawyer, the government has to provide the alien with another lawyer, to be paid for out of a $25 fee that is tacked onto the fees paid by all other applicants for benefits under H.R. 6 (unless of course, fees are waived, in which case, those applicants will pay nothing).

Aliens who are subject to a provisional denial of their Dream Act of 2021 applications by the secretary of DHS don't even need to prove that they cannot afford a lawyer. All they have to do is ask for one, and the government must provide one.

Here is why it is called a "provisional denial". After the district court judge has reviewed that secretary's decision, the court is supposed to return the case to the secretary for a final decision.

Of course, even then the matter is not really final, because the alien can thereafter claim that he or she did not contest the provisional denial because the alien did not get notice of it (or any other reason that constitutes "good cause", including the fact that the alien was incarcerated, logically), notwithstanding the fact that the secretary has to send out notice — twice.

Assuming that the alien applicant goes all the way through this process and receives a final denial of his or her application, it really puts that alien in no worse position than he or she currently occupies: DHS still has to place the alien into removal proceedings. That means that the applicant can contest removal, and apply for any other form of relief or protection.

Even if the alien respondent receives a final order of removal from the immigration judge, that respondent can file an appeal with the Board of Immigration Appeals, by right (no paid counsel in any of those proceedings yet, however). And, if the respondent receives a final order of removal, he or she can file a petition for review with the applicable circuit court, and then request certiorari from the Supreme Court.

Do the math.

Under paragraph 102(c)(3) of the "Dream Act of 2021", it can take six months for the secretary of DHS to issue a preliminary denial, and more than an additional year for a district court to issue a decision in the alien's case (longer if the government gets the alien a really good lawyer), in the case of an alien whom the secretary of DHS determines is "a significant and continuing threat to public safety" or a gang participant.

Do you really think that the government is going to detain that alien for two years-plus? How about for the two to 10 years that his or her case wends its way through the removal process? I hope so, but seriously doubt it.

The sponsors of this legislation must have a dim view of the secretary of DHS's capacity, discretion, and powers of discernment to place all of these restrictions on him. Or I am plainly reading this incorrectly.

Regrettably, I do not think I am.